The senators could not believe their good fortune. They could now make campaign promises and spend at will! There was no reason to balance the budget or raise taxes to pay for the spending.

So every year the government issued more Fish Reserve Notes than the bank had savings to redeem. When the deposits got low, the fish technicians worked their magic. The mix proved to be intoxicating. And despite their gnawing urge to contain the situation, and to get back to a sustainable path, the senators just couldn't help themselves.

Some of the projects funded by government provided some benefit to all. The island navy got bigger canoes, which kept the Bongobians at bay; and a new system of cart paths made transportation easier. However, the benefits provided by the controversial Clean Rocks Jobs Program were much harder to quantify. But whether shiny rocks were something the island actually needed did not diminish the program's popularity to those who got the jobs.

Meanwhile the new government Fishing Department got up and running. By offering generous benefits and salaries, the department easily hired workers. Those who got the jobs loved the steady work, and happily voted for their senatorial patrons.

But beneath the surface, there were real problems brewing.

With no personal incentives to take risks and make profits, the Fishing Department failed to become a model of efficiency.

The rate of increase of actual fish production did not rise as fast as the supply of Fish Reserve Notes that the Senate put into circulation.

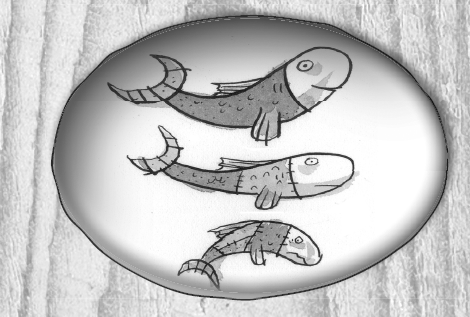

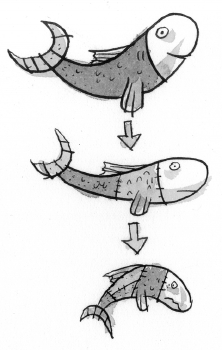

Soon so many Fish Reserve Notes had been issued that the technicians had to increase the conversion rate. Ten to nine gave way to five to four. This meant that official fish were now 20 percent smaller than real fish.

When that proved insufficient, the conversion dropped to three to two, and eventually two to one.

As official fish became smaller and smaller, it soon became apparent that the islanders could no longer survive on just one fish per day. Most now ate two per day, at minimum.

Given that fish were used as money on the island, prices for everything had to go up to keep pace with the diminished nutritional value of fish. The nagging problem of "fishflation" was born. So while efficiency had traditionally driven prices down, now government-created fishflation forced them in the opposite direction.

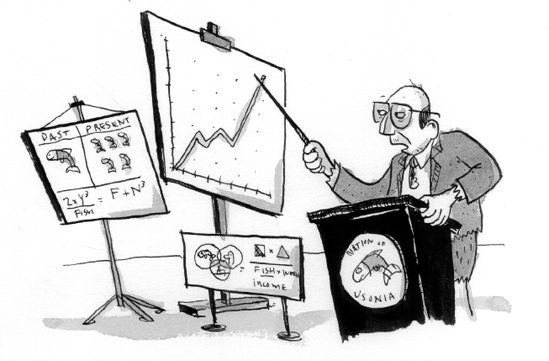

Strangely, no one could agree on why prices were going up. Ally Greenfin offered a needed theory. "Fishflation," he said, "is caused by a phenomenon known as the 'cost-price-fish push.'" He argued that high employment (thanks in part to government jobs) combined with a strong economy creates greater demand for fish and forces up prices.

As proof of their prosperity Greenfin noted that most islanders were now eating twice as many fish as their parents.

Greenfin warned that without the stimulus that is provided by a steady dose of fishflation, people would lose their appetites, and stop demanding fish, and the island economy would contract. He further theorized that a fishflation level of only one-half of a fish belly per year would be optimal. Fishflation, he argued, was essential to an expanding economy!

"Nice figuring, Ally. You could talk a shark out of a fish barrel," said Franky. But nobody thought of pointing a finger at government, the real cause of fishflation!

With a blank check to do whatever it wanted, the government continued to curry favor with citizens by issuing more and more Fish Reserve Notes. As it did, the official fish continued to shrink in size and the fish became less and less valuable. Wages and prices, therefore, had to go up. Although in some years the fishflation was barely noticeable because of offsetting productivity gains, two things were certain: the fish never got bigger, and prices rarely went down!

When fishflation became rapid, islanders finally noticed that the fish they withdrew from the bank were smaller than the fish they deposited. So, despite the enticement of interest paid on their savings, they began to save less while many discontinued saving completely. Instead, fish had to be spent quickly to avoid losses due to rapidly increasing prices.

The real burden of this rapid fishflation fell on retirees. Those who had deposited fish in the bank during their working years found that they had to eat two or three fish per day just to survive. The savings that they had hoped would last for 20 years, were gone in just four or five.

Since fishflation discouraged saving, bank deposits dwindled. As a result, there were less fish available to fund promising projects or prop up sagging businesses. In response, businesses cut back and workers were laid off. Desperate to offset the effects of fishflation, many more islanders decided to risk thier savings with Manny Fund, whose promise of oversized returns gave investors the best hope of overcoming these losses.

When unemployment reached a crisis level, people demanded that the government do something.

The Senate tried to make jobs more secure by setting strict limits on how much companies could pay workers, and under what circumstances the workers could be hired and fired. The resulting constraints made it more difficult to do business, and limited the ability of businesses to grow.

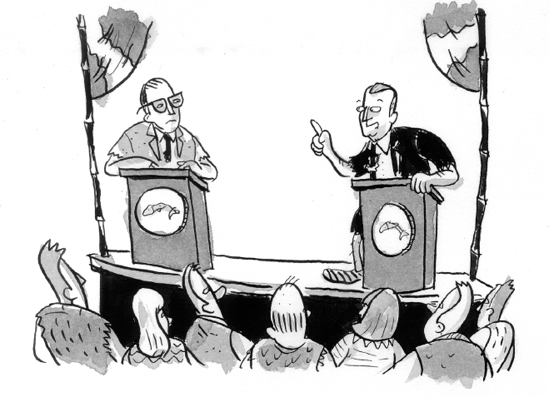

As time passed, a new senator, Lindy B., saw another electoral opportunity...this time to make a Great Society! Lindy promised that if elected not only would he furnish the canoe navy with bigger spears, but he would also help the sagging economy by providing emergency unemployment fish notes to all laid-off workers.

His opponent, Buddy Goldfish, offered nothing but careful stewardship of the island's savings and boring protection for the islanders' economic liberties. More importantly, Buddy argued that the island could not afford such an extravagant "spears and fish" policy.

Not surprisingly, Lindy won in a landslide.

And so the process continued. Fish Reserve Notes were produced in ever greater numbers while the fishing fleet returned with fewer and fewer actual fish.

As official fish shrank to just one-tenth of their former size, even Ally Greenfin knew that he could not stretch the fish skin any further. When there were just bones left in the vault, he ran over to the Senate and called an emergency meeting.

One of the reasons that economists have been so successful in obscuring the source of inflation is that they have short-circuited the very definition of the word. Nearly everyone believes that rising prices means inflation. So if prices aren't rising, there must be no inflation.

But rising prices are merely the results of inflation! The inflation is the expansion of the money supply.

Any dictionary printed before 1990 defines inflation purely as an expansion of the money supply. Newer editions have hedged their bets. But if you understand the true definition, you know that it is possible that prices can stay flat, or even fall, while the money supply itself is being inflated.

During a recession people wisely stop spending. When they do, demand drops and prices should fall. But sometimes these forces are counterbalanced by an expanding money supply that diminishes the value of currency. When inflation is present in a recession, prices may go up (if the printing is fast enough), stay flat, or fall less than they would have with no inflation.

But during a recession prices need to fall in order to rebalance the economy. Recessions should be deflationary. Falling prices will cushion the blow of low employment. Somehow, modern economists see falling prices as a never-ending abyss toward demand destruction. They forget that when prices fall far enough, people start spending again. The process allows unneeded inventories to be worked off, and for prices to fall to a level justified by underlying supply and demand.

By keeping prices artificially high, inflation prevents this from happening.

Governments now reflexively fight recession by creating money. If they go too far, they can produce inflation and recession simultaneously, leading to a condition called "stagflation," which flourished in the 1970's. Conveniently forgetting that episode in the 1970's, economists now insist that infl ation and unemployment can't co-exist. They argue that when people lose their jobs, demand falls and proces follow. They forget the other side of the equation. When fewer people are working, less stuff is produced, reducing supply. When things are scarce, prices rise. Adding more money into the mix could cause prices to soar.