Humans are undoubtedly nature’s most versatile problem-solvers to date. As we’ve seen, the key to our success lies in the interplay of two kinds of mental activity:

- Intuitive problem-solving is the work of unconscious pattern-matching: it looks for similarities between problems and puts problems in context to help us decide what to do.

- Rational problem-solving is the work of conscious, deliberate thinking: it uses logic, evidence and evaluation according to objective criteria, rather than association with experience.

And where does this intuitive and rational thinking happen? The obvious answer is: in our brains.

In this chapter we’ll take a tour of the brain, exploring the different ways in which it can help us to solve problems – and sometimes get in the way. We’ll look at:

- how emotions can solve problems for us (or not);

- how problems cause stress, how the stress response works and how we can manage it;

- how reasoning can open up our thinking to new explanations and arguments;

- how our multiple intelligences help us specialize as problem-solvers; and

- how cognitive fluidity opens up huge potential in our problem-solving capabilities.

And because all of these different elements operate inside our heads, it makes sense at this point to take ...

A quick tour of your brain

Your brain is the most complex system known to man. It weighs about 1.4 kilograms and contains about 100 billion neurons. Each neuron can make contact with thousands of others, using structures called synapses. Your brain makes a million connections between neurons every second, mapping out networks of connections that grow, combine and change as you think and feel. The brain’s neural networks are infinitely flexible; and the number of possible neural networks in one brain easily exceeds the number of particles in the known universe.

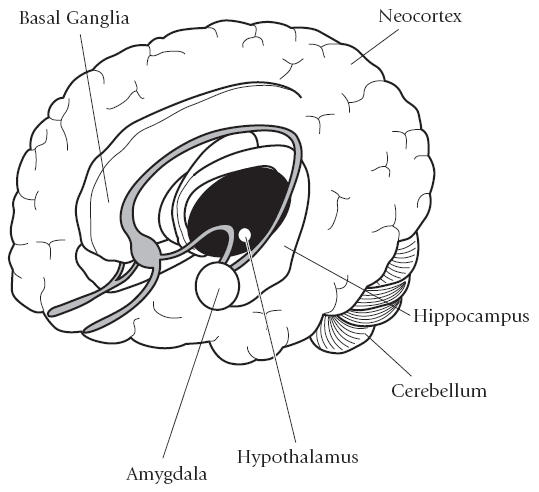

One way to simplify the workings of this extraordinary organ is to concentrate on three areas:

- the basal ganglia;

- the limbic system; and

- the neocortex.

Each system represents a different stage in our ability to solve problems.

Interestingly, these systems are stacked around each other in the brain: the basal ganglia at the centre, surrounded by the limbic system, with the neocortex folded over the top (see Figure 2.1).

The basal ganglia: helping us do what we know how to do

The basal ganglia are situated at the base of the forebrain. The most intuitive of our intuitive problem-solving happens here.

In particular, the basal ganglia are associated with what the experts call ‘procedural memory’. We use procedural memory to perform repeated actions unconsciously: typing or driving a car, singing or playing tennis. By performing the same task many times, we teach our brain to ‘pattern in’ all the relevant neural systems to work together automatically.

Many problems are interruptions to procedural memory. That feeling of stuckness may arise because something has taken us ‘out of procedure’. (We explore this situation more fully in Chapter 4.)

Figure 2.1 The human brain

What to do

Problems that interrupt procedural memory

Think about the last time your procedural memory was interrupted. What was your response?

All sorts of things can disrupt our procedural memory. Imagine trying to teach a child how to tie their shoelaces. Imagine suddenly losing control of the steering while driving, or trying to read a newspaper upside down. In such situations, procedural memory can’t operate and we are forced to concentrate consciously on what we’re doing: instead of performing like an expert, we’re suddenly stumbling about like a beginner (a condition known as ‘choking’).

Because procedural memory is unconscious, ‘choking’ can cause strong unconscious responses: anger, frustration or stress.

The limbic system: emotions, memories and stress responses

The limbic system influences intuitive problem-solving by regulating memory and emotion. This area consists of a number of structures, including:

- the hippocampus (named for its shape: it’s the Latin for ‘seahorse’), which is crucial for memory; and

- the amygdala (again named for its shape: the Latin for ‘almond’), which is closely associated with our emotions (it’s been called ‘the brain’s alarm system’).

The term ‘limbic’ comes from the Latin limbus, meaning ‘border’. The limbic system sits in the borderland between the conscious and the unconscious. On the one hand, it’s a crucial component of intuitive problem-solving: it influences the body’s various nervous systems and the release of hormones – all of which governs our behaviour unconsciously. On the other hand, the limbic system is closely wired into the neocortex, where most of our rational problem-solving goes on.

The neocortex: reasoning, planning and communicating

The neocortex sits on and around the rest of the brain, and it’s where we do most of our rational problem-solving. It’s a sheet of material – no more than two or three millimetres thick – that’s responsible for speech, working memory, planning and reasoning. If unfolded, your neocortex would be about the size of a dinner napkin.

Everything we think about with our neocortex has arrived there by way of the limbic system. That’s one reason why intuitive and rational problem-solving can only work well if they work together.

How our emotions solve problems for us

We saw in Chapter 1 how we solve many problems intuitively, by pattern-matching. We fit new experiences to mental models that tell us what to do. And pattern-matching seems to happen not so much in the neocortex but in the limbic system.

The limbic system acts as a kind of mental receptionist for all external stimuli. It analyses an external stimulus to decide whether it’s familiar (through memory) and whether it’s friendly or threatening (the basic emotional response). It’s the limbic system that tells you whether the shadow in the corner is a ghost or your dressing gown. It’s the limbic system that activates the stress response when you start a public speaking engagement, and defuses it after a few minutes as you discover that it’s going well. As Daniel Goleman explains in Emotional Intelligence:

‘When we are in the grip of craving or fury, head-over-heels in love or recoiling in dread, it is the limbic system that has us in its grip.’

The limbic system pattern-matches to a stimulus before sending information to the neorcortex. It can be anything up to half a second before we become consciously aware of what our limbic system has already responded to. And by that time, the amygdala has told us how to react, by generating an emotional response.

Emotions are the limbic system’s problem-solving tools. Their function is to make us act. (The word ‘emotion’ of course includes the word ‘motion’, and derives from a Latin word meaning ‘to remove, expel, to banish from the mind, to shift or to displace’.)

Emotions are simple. According to Paul Ekman, an anthropologist who has studied the expression of emotions around the world, humans exhibit six basic emotions. Each emotion is a mental model that provides a solution for a presented problem:

- Anger causes our heart rate to go up, providing more oxygen to the main muscle groups, and blood flows to our hands to help us grasp a weapon. Anger also triggers the release of adrenaline to give us energy and increased attention.

- Fear, in contrast, sends blood to the legs and feet, to help us run away. In consequence our faces become pale and cold (our ‘blood runs cold’). Hormones put us on general alert and fix our attention on the single point where we perceive the threat.

- Surprise opens the eyes to allow us to see more.

- Sadness slows the metabolism and decreases energy, so that we move and do less – perhaps allowing us to stay close to others who will care for us.

- Disgust is principally mediated through the sense of smell (we ‘turn up our nose’ at something), probably to protect us from poisonous or decayed food.

- Happiness relaxes bodily systems, reduces blood pressure and slows breathing so that we can remain calm. Brain activity inhibits negative emotions and prepares us to work or achieve a goal.

The limbic system can act in two ways. When emotional arousal is low, the limbic system does some contextual thinking, interrogating the pattern-match and comparing it to previous experiences. It then sends information up into the neocortex, which can decide the appropriate response to this specific problem.

If an emotional arousal is strong enough, however, the limbic system adopts a fast-track approach. It cuts off connections with the neocortex, so that information cannot reach the conscious mind. Instead, we act directly on the emotion. We explode with anger, collapse into tears, cry out with surprise, recoil with disgust, scream with fear or burst out laughing. In the words of Daniel Goleman, the limbic system hijacks the neocortex.

When an emotion is solving a problem for us, we act without thinking. If we’re highly aroused emotionally, we can’t think rationally.

What to do

Is emotion clouding your judgement?

If you think that emotion is preventing you from thinking clearly about a problem, there’s only one wise solution: lower the emotional arousal.

Walk away; buy time; discharge the emotion physically by taking exercise, having a good cry or relaxing.

Are you having to deal with another person who is emotionally aroused?

The same principle applies. You will not be able to reason with them. Their brain is being hijacked by their limbic system, and emotion is telling them what to do.

You can either leave them alone, or help them to lower the emotional arousal. Help can be in the form of distracting conversation or activity, telling them to concentrate on their breathing, or assuring them that there is time to calm down. (These are techniques usefully put into practice by the parents of toddlers the world over, to stop tantrums. You can adopt the same techniques, when necessary, with your manager.)

It is never a good idea to fuel the emotional arousal by responding emotionally.

Emotions are part of intuitive problem-solving’s repertoire of solutions. They are valid as long as the problem warrants the emotional arousal. But if we respond to a problem using only our emotions, we may find that the solution is inappropriate or inadequate.

Intuitive problem-solving, therefore, benefits from some emotional intelligence (EI). According to Daniel Goleman, EI embraces two kinds of awareness:

- understanding ourselves, our goals, intentions, responses, feelings and behaviours; and

- understanding others’ goals, intentions, responses, feelings and behaviours.

By knowing what arouses our emotions, we can better manage them. By recognizing emotional responses in others, we can help them manage their emotions. By understanding how emotions work, we can deal with them more calmly and productively.

Problems and stress

Problems can cause stress. And we also know that stress is bad for our well-being. Understanding stress is critically important if we want to become better problem-solvers – and if we want to remain healthy.

Stress is one of the inevitable consequences of being stuck. If we want to do something, but we don’t know what to do, we feel vulnerable in a situation of potential danger. That’s stress. The environmental nasties – the things we call problems – are usually called stressors, and the reactions they stimulate – biological and psychological – are referred to as the stress response.

Stress is the interaction of stressors and stress response. The same stressor can cause wildly different responses in different people; and the same level of response can be triggered by very different stressors. The collapsed omelette that causes one cook to explode in frustration may cause barely a shrug in another. A fault on a computer may rouse one user to intense interest and cause considerable anxiety in another. An encounter with poor road manners can trigger laughter in some drivers but road rage in others.

The stress response is another of nature’s intuitive problem-solving mechanisms. In essence, it’s a two-track process. Here’s how it works.

Fight or flight

As with emotions, the stress response is born in the limbic system. It operates unconsciously; our chances of survival are better if we act without thinking.

If the limbic system identifies a stressor, it activates the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). The normal function of the SNS is to maintain our bodies in a state of dynamic equilibrium called homeostasis, by regulating temperature, blood sugar levels, digestive acids and so on. When faced with a stressor, the system releases adrenaline and noradrenaline; these two hormones trigger the fight-or-flight response.

Fight or flight seeks to solve a problem by switching priorities: from long-term homeostasis to short-term survival. It’s this switching of priorities that causes the familiar symptoms of the response:

- Fuel is transported rapidly through the blood system to the brain. (Pulse and blood pressure rise.)

- Blood is taken from the smaller muscle groups at our extremities to the larger muscle groups. (We get cold feet – literally.)

- Systems regulating long-term well-being (growth, digestion, sex) are sacrificed in favour of the systems that will help you fight or fly. (We lose appetite and our ability to salivate, we get ‘butterflies in the stomach’ and a dry mouth. Libido collapses.)

- The pupils dilate (so that we can see more) and we get ‘tunnel vision’.

- Our palms and feet become sweaty to improve our grip.

- Alertness and reaction times are improved (we become ‘jumpy’).

- Sphincters at each end of the digestive system relax: we become nauseous and may feel the need to defecate or urinate, partly to lose weight and partly, perhaps, to make us less attractive to a predator.

As a result, fight or flight is a double-edged problem-solving sword. It’s vital if we’re facing an imminent threat to our physical safety, but it’s not so helpful if the problem is more complicated, subtle or long-lasting. As a response to the stressors of modern life, it can be wildly inappropriate. We may want to decapitate our manager when they make unreasonable demands, or rush screaming from a meeting when an argument gets heated, but those options are not (usually) available.

Can stress help us to solve problems?

Yes, it can.

For a start, it makes us concentrate. Adrenaline and noradrenaline help us to focus on the problem at hand. This single-mindedness comes at a cost, however: we become unable to think flexibly. As with intense emotional arousal, heightened stress cuts the neural pathways between the limbic system and the neocortex, making us less capable of rational thought and subtle discrimination.

Fight or flight also seems to include a reward for enduring the stress. The response includes the release of endorphins: chemicals not unlike morphine or heroin. Endorphins relax us; at high levels, they can lower our perception of pain. They also seem to be partly responsible for our feelings of satisfaction or elation when we’ve endured a stressful experience. Endorphins may be implicated in ‘runners’ high’, the euphoria some athletes experience after strenuous exercise.

These benefits, however, also come at a cost. The same endorphins that suppress pain and give us ‘natural highs’ can suppress the activity of natural killer cells and increase the risk of developing tumours.

The key seems to be to keep stress levels at an intermediate level: too much stress – or too little – and performance suffers. Indeed, if the stress response is brief, mild and – crucially – controllable it can become positively enjoyable. This kind of positive stress has been called eustress. The term’s not often used, but we’ve all experienced eustress in the thrill of a rollercoaster ride or a horror movie. We can induce eustress by winning a race, getting a promotion – or by solving a really tough problem.

The really good news is that the fight-or-flight response is short-lived. It kicks in within 30 seconds of a stressor being identified, and usually subsides within about an hour.

If the stressor doesn’t go away, however – or if we face a series of short-term stressors over a period of time – we may find ourselves succumbing to a second stress response. And it’s far more serious than the first.

Long-term stress and its dangers

This second response is activated by the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal system (the HPA axis, as it’s sometimes known). A complicated sequence of electrical and chemical messages in this system releases a cocktail of substances, among the most important of which is cortisol.

Cortisol is a substance not unlike the steroids doctors use to treat inflammation and allergies. Its function is to convert energy reserves into forms the body can use immediately. Normally, levels of cortisol rise and fall rhythmically during the day, in line with our demand for energy.

Persistently high levels of cortisol can cause serious harm. Long-term disruption of cortisol’s natural cycle, for example, can lead to insomnia, burnout or chronic fatigue – not to mention a range of mood disorders including depression, anxiety and addiction. Over time, cortisol can suppress the immune system, making us more susceptible to infection. By mobilizing energy reserves, cortisol can release fatty acids into the bloodstream, increasing the risk of clogged arteries and heart disease. Other chemical reactions can contribute to a whole range of mood disorders, including depression, anxiety and alcoholism.

What makes long-term stress even more serious is the very fact that it is long-lasting. Unlike the fight-or-flight response, which can subside within an hour, the long-term stress response can persist for days, or even weeks.

And it gets worse

Stress may bring some benefits, but overall it does a lot more harm than good.

The two stress responses operate in a complicated relationship. Exposing ourselves to multiple small stressors can activate the longer, slower response. Continual small-scale problem-solving (‘fire-fighting’) can result in long-term stress.

And the stress responses can’t be suppressed – only discharged. Pretending that we’re not suffering stress, or trying to struggle on and ignore the symptoms of long-term stress, simply fuels the response. The only way to reduce stress is to reduce the levels of stress-inducing substances.

What to do

Are you suffering from long-term stress?

Check out these symptoms (the list is not exhaustive). They often accumulate until you are forced to take notice of them. You may notice the behavioural symptoms first; but they can show themselves after stress has been going on for some time.

Don’t rationalize the symptoms away. If you’re not sure, ask your GP.

Behavioural signs

- Becoming a workaholic: no time to relax

- Poor time management or poor standards of work

- Absenteeism

- Social withdrawal and relationship problems

- Insomnia or waking tired

Psychological signs

- Inability to concentrate or make simple decisions

- Memory lapses

- Depression and anxiety

Emotional signs

- Tearfulness and irritability

- Mood swings: sudden outbursts of anger or frustration

- Feeling out of control

- Lack of motivation

- Lack of confidence or self-esteem

Physical signs

- Aches and pains, muscle tension, grinding teeth

- Frequent colds or infections

- Constipation, diarrhoea, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- Weight loss or gain

- Indigestion, heartburn, ulcers, nausea

- Dizziness, palpitations

- Panic attacks

- Physical tiredness

- Menstrual changes, loss of libido, sexual problems

- Heart problems, high blood pressure

What can stress teach us?

What’s the moral of all this for us, as problem-solvers?

Problems cause stress. Stress is the result of an interaction between a stressor and a stress response. The interaction varies greatly between individuals, but it always works on two levels: short-term and long-term.

Short-term stress can help us solve problems. It increases concentration and includes a built-in reward mechanism to make us feel good when we’ve solved the problem.

Long-term stress, in contrast, is almost entirely harmful. It can increase the risk of infection, heart disease, skin rashes, high blood pressure, migraine, asthma, gastrointestinal disease, depression, anxiety, addiction and some cancers. It can even affect the ageing process.

The stress response limits our ability to think fluidly. It shuts down contextual thinking, inhibits rational thinking and promotes action. We can never, therefore, successfully suppress a stress response; we can only successfully discharge it.

How to manage your stress responses

If we want to develop our problem-solving abilities, we need to be able to manage our stress responses.

We can manage stress in many ways. We could seek to discharge the stress response physically; we could manage our diet and examine our environment for sources of unnecessary stress; and we could manage our own behaviour to make us more tolerant of stress. Finally, we could seek to deal with the stressor itself: we could start to develop our problem-solving skills.

Exercise and breathing

The stress response is physical. It makes sense, therefore, to find ways of discharging the response physically.

The stress response is designed to make us respond to problems with vigorous action; but most of us face stressors while sitting at desks or at the wheels of our cars. Regular exercise helps to dispel stress hormones and other neurochemicals, and keeps them at healthy levels. Exercise also helps us sleep better, almost certainly helps us think better and is a potent antidepressant.

What to do

7:11 breathing

One of the first things to suffer when we get stressed is our breathing. In particular, we start breathing in more than we breathe out. Result: we start to asphyxiate. This exercise is designed to reverse the behaviour. The aim is to breathe out more than you breathe in. It will automatically calm you and reduce your stress level. Guaranteed!

- Assume a comfortable position if possible and close your eyes if you wish.

- Take a slow breath in to the count of 7.

- Hold for a few seconds.

- Release your breath out slowly to the count of 11.

- Hold for a few seconds.

Repeat as necessary until you feel yourself calm down.

Any activity that involves deep breathing is likely to be effective in reducing stress: singing, cycling, swimming ... Meditation, too, starts with an emphasis on effective breathing. Find what works for you.

Food, drink and other substances

Diet can be a surprisingly important factor in making us vulnerable to stress. If you want to reduce your predisposition to stress, you could consider moderating your intake of these kinds of foods:

- sugar-high foods;

- foods high in salt;

- caffeine;

- foods deficient in Vitamin C and the Vitamin B complex;

- alcohol;

- nicotine.

Removing environmental stressors

Many environmental stressors are avoidable. If you have a headache because you’ve been reading with poor light, move to another room where the lighting is better. Manage noise levels and think about the design of the chairs you use regularly. Changing your surroundings can mean turning on lights, turning off loud music, raising or lowering your computer chair.

Public spaces can be particularly stressful. Make a careful survey of the places where you spend a good deal of your time. Check your surroundings carefully for potential situational stressors.

Looking after yourself

It’s critically important to stop problems overwhelming you. All problems change if we change our response to them. Look after yourself and you’ll be able to deal with problems far more effectively:

- Take breaks. Take a lunch break and don’t talk about work. Take a walk instead of a coffee break. Use weekends to relax, and don’t schedule so many leisure events that Monday morning will seem like a relief. Take regular holidays, long weekends or mental-health days at intervals that you have learned are right for you.

- Create predictability in your work and home life. Structure and routine in your life can’t prevent every surprise, but they can provide the security we all need to be able to deal with the unexpected. Plan ahead.

- Share problems with others. Getting someone else’s perspective on a problem can help you gain perspective and reduce stress. It can also be helpful for the other person to know that you’re facing a problem, so that they can understand your situation and help you more effectively.

- Learn to say ‘no’. Find your own limits and exercise your skill in keeping to them. You’re not much use to others if you’re not looking after yourself. You may benefit from developing your time management skills; learn to delegate.

Reasoning: the work of deliberate thought

With reasoning, it seems, we finally emerge from the dark recesses of the limbic system to the higher reaches of the neocortex. It’s here, in the (literally) highest parts of the brain, that we do the deliberate, conscious work of rational problem-solving.

We saw in Chapter 1 that three key principles dictate the workings of rational problem-solving:

- Understanding the problem and solving the problem are two distinct forms of thinking.

- Making sense of the problem always means testing our understanding against objective criteria and evidence.

- Generating a solution always involves building feasibility into the action we propose to take.

And we do all of this consciously, deliberately and – compared to the lightning responses of intuition, emotion or stress –relatively slowly.

What to do

A crash course in reasoning

To become more competent at rational thinking, follow these simple guidelines.

Reasoning is purposeful:

- Define the problem you’re trying to solve as clearly as you can.

- Distinguish the problem from similar or related problems.

- Review your problem definition regularly.

Reasoning always starts from a point of view, a position or an assumption:

- Identify your point of view.

- Identify the assumptions lying behind your point of view and justify them.

- Ask how your assumptions are influencing your definition of the problem.

- Seek other points of view and identify their strengths as well as weaknesses.

Reasoning looks for different views of the problem:

- Express the problem in several ways to clarify its meaning and scope.

- Break the problem into sub-problems.

- Ask whether the problem is a question of truth or action.

- Ask whether you need to use different kinds of reasoning for different parts of the problem.

Reasoning is expressed by, and works with, ideas:

- Identify the key ideas that inform your understanding of the problem.

- Express all key ideas as sentences. Headings or names are not concepts and cannot be assembled into arguments.

- Look for the assumptions underlying your ideas and challenge them.

- Consider alternative ideas – especially ideas that contradict your key ideas.

Reasoning assembles ideas into arguments leading to conclusions:

- Identify the idea that is your conclusion, and the ideas that act as reasons to support or lead to the conclusion.

- Ask how the reasons connect to the conclusion.

Reasoning is based on evidence:

- Ask how the data and information you’re using acts as evidence for your ideas.

- Search for evidence to disprove your ideas.

Reasoning has consequences:

- Trace the implications of your conclusion.

- Ask how your conclusion implies a course of action.

- Identify the consequences of your chosen course of action.

We usually think of rationality as being separate from intuition and emotion. We’re fascinated with characters who can rationalize without being ‘infected’ by feeling: think of Sherlock Holmes, Mr Spock, or Stanley Kubrick’s famous computer Hal (in 2001: A Space Odyssey).

In truth, of course, reason and intuition are complementary. Our minds can reason only with material we observe, and most of our perception is intuitive. Rationality in the real world constantly cycles between theory and observation, each continually modifying the other. The very act of forming a hypothesis involves recognizing a pattern or a trend: and recognizing patterns is, in essence, intuitive. If we notice that people are falling ill more frequently in one region than in neighbouring regions, it’s not logic but intuition that connects the observations into a pattern and tells us something’s not right.

Rationality, then, can never operate entirely without intuition. Just as the different parts of the brain operate together, in networks of staggeringly complexity, so we might say that rational problem-solving works best when it’s linked to intuition.

And we might say that our ability to combine rationality and intuition to solve problems is a measure of our intelligence.

Intelligence or intelligences?

Intelligence is a tricky concept to pin down. We associate it with quick reasoning: to be labelled ‘slow’, all too often, is to be regarded as unintelligent. Yet rapid reasoning often makes mistakes. We might confuse intelligence with having lots of knowledge (a confusion encouraged by numerous quiz shows on television); but it’s obvious that knowing lots of facts hardly makes someone intelligent. Intelligence quotient (or IQ) is probably the most familiar marker of intelligence; yet IQ has its critics. IQ arguably measures only the more rational aspects of intelligence: our powers of logical deduction, in particular.

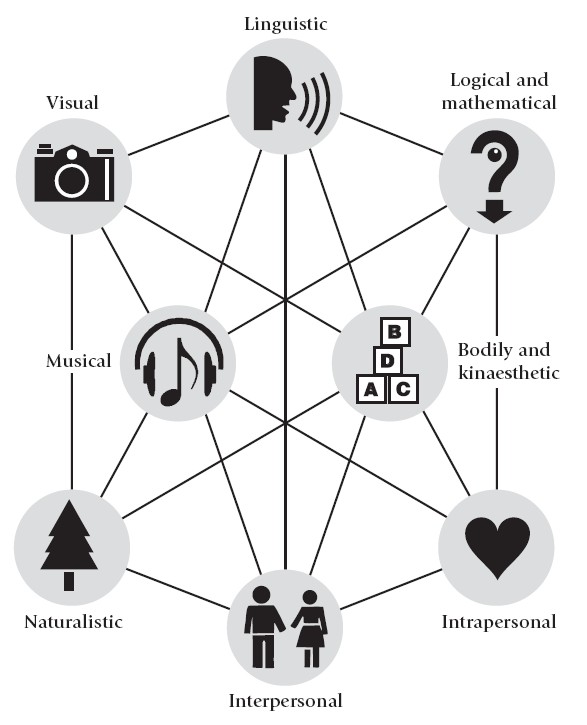

Some scientists argue that the mind is made up of multiple intelligences. Howard Gardner, for example, claims to be able to identify eight different types of intelligence (see Figure 2.2). Six relate to our environment: visual, linguistic, logical and mathematical, bodily and kinaesthetic, musical and naturalistic. Gardner completes his list with two types of personal intelligence: interpersonal, which helps us deal with others; and intrapersonal, which helps us examine our own thinking and behaviour.

Figure 2.2 Gardner’s eight types of intelligence

Gardner defines intelligence in terms of problem-solving. In his book Frames of Mind, he writes that, as he sees it, intelligence must be a competence: it ‘must entail a set of skills of problem solving – enabling the individual to resolve genuine problems or difficulties that he or she encounters’. Intelligence, he suggests, is not just a way of dealing with problems we encounter, it ‘must also entail the potential for finding or creating problems – and thereby laying the groundwork for the acquisition of new knowledge’ (my emphasis).

All of Gardner’s intelligences are functional: they all help us do things rather than simply knowing things. Visual intelligence tells us how to move, linguistic intelligence how to speak, interpersonal intelligence how to behave with others and so on. The theory of multiple intelligences links the brain intimately to the body and reminds us that a solution isn’t merely an answer to a question – it’s something we do.

Gardner points out that his multiple intelligences constantly interact. We can build connections between them to help us solve ever more complex problems. And this idea, too, makes sense. How could musical intelligence operate without invoking bodily and kinaesthetic intelligence to help us sing, dance or play an instrument? How could our linguistic intelligence reach its potential without an interpersonal intelligence to help us understand the impact of our words on others?

And it’s because our various intelligences can interact that we can solve problems in so many different ways. Another name for it is ‘cognitive fluidity’.

Cognitive fluidity: your mind is (like) a cathedral

Cognitive fluidity is our ability to combine different kinds of intelligence to create new ideas.

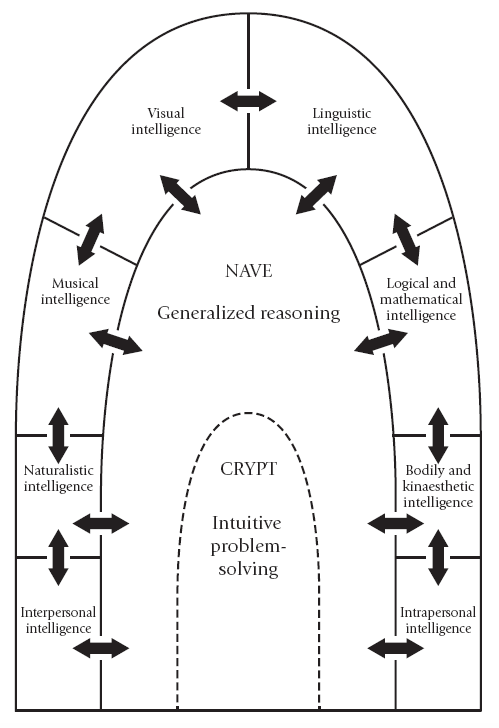

Imagine that your mind is like a cathedral. (This idea is based on a model devised by Stephen Mithen in his book, The Prehistory of the Mind. I’ve added one or two elements and adapted his brilliant image for my own purposes.)

This cathedral, like most great cathedrals, has grown up over time; in this case, evolutionary time:

- Underlying the whole edifice is an underground complex: we could call it the ‘crypt’. This is where our intuitive problem-solving goes on, matching information to mental models unconsciously.

- Above the crypt is the central ‘nave’ of the cathedral, where we do generalized reasoning.

- Around the ‘nave’ are groups of ‘chapels’, each devoted to a specialized intelligence. We might envisage eight, corresponding to Howard Gardner’s multiple intelligences. And we might envisage more and more ‘chapels’ attaching themselves to the cathedral as we acquire new specialized intelligences.

Figure 2.3 The cathedral of the mind

Each of these areas of the cathedral is an area of the mind. Each is distinct, but all are connected: we can imagine doors and windows linking the ‘chapels’ to the ‘nave’, as well as stairways leading down from all parts of the building into the ‘crypt’.

Our thoughts, like pilgrims, can wander at will around the cathedral, taking ideas and information from one ‘chapel’ into another, enriching material in different ‘chapels’ with the general reasoning powers of the ‘nave’, descending into the ‘crypt’ and bringing its insights up into the main building.

This is cognitive fluidity. Our multiple intelligences allow us to specialize; cognitive fluidity is the source of our ability to innovate. By combining different intelligences, we can create new solutions to old problems and identify entirely new problems to solve.

Indeed, cognitive fluidity is the source of that most powerful problem-solving tool: imagination.

Chapels, cubicles and silos

Humans are mental specialists – it’s an inevitable consequence of intuitive problem-solving. As we saw in Chapter 1, the natural tendency of pattern-matching is to grow expertise in specific fields of experience and knowledge. We think, learn and operate in discrete ‘chapels’ of knowledge and skill, developing our abilities in greater detail and depth.

Our organizations reflect this specializing tendency. We define ourselves in terms of functional specialisms. We become ‘cubicle workers’. The ‘chapels’ of Stephen Mithen’s mental cathedral have become the ‘silos’ of the modern corporation. And breaking down the walls between them can be difficult.

Yet many problems demand ‘cross-cubicle’ thinking: a patient being treated by a group of medical specialists; a product-development team innovating a new product or service; a film production using the skills of actors, writers, musicians and a range of technical experts. Social and political problems demand cognitive fluidity, too. Our success as a species is built on cognitive fluidity.

How can we break down the walls in the cathedrals of our minds? What’s the secret of cognitive fluidity?

I talk, therefore I solve problems

The answer is language. Language allows us to think about things in terms of other things. It helps us to think in new ways, about new things. With language, we can transform our ideas into new ideas. How? In three ways.

First, language allows us to articulate our intuitions. We can bring our hunches and insights into the light of consciousness, to reflect on them, challenge them, work with them and – sometimes – act on them.

Second, language allows us to reason. By reasoning we can make sense of the world more objectively than by relying simply on intuition and experience. We can work out what evidence means, and sort evidence into meaningful categories. Language allows us to construct ideas with which we can generalize from evidence. And with language we can assemble our ideas into explanations, by which we can evaluate the significance of what we know, and arguments, which give us objective reasons for choosing solutions.

But language, finally, is also the key to cognitive fluidity. With language, we can create associations between things, in terms of closeness, opposition or similarity. Associative thinking opens up the possibility of thinking about things in terms of other things: by means of simile, analogy and metaphor. Language – to speak metaphorically – is the power that blows holes in the walls of our mental cathedrals, allowing us to combine intelligences in pursuit of new ideas and innovations. All of these faculties put us in touch with the wellsprings of intuitive problem-solving and take it to a new level, in which we can exercise our imagination to visualize past events, future scenarios and alternative realities. (We’ll explore these powers in more detail in Chapter 9.)

Language, then, allows us to combine the strengths of intuitive and rational problem-solving. And it does one thing more. Language allows us to share our thinking – to offer our thinking for others to inspect; and to take the thinking of other people and develop it. Language is the key to collaboration. (And we’ll investigate the challenges of collaboration in Chapter 11.)

In brief

The human brain contains three main systems that help us to solve problems in different ways:

- the basal ganglia;

- the limbic system; and

- the neocortex.

The basal ganglia are associated with procedural memory. The limbic system mediates emotional and stress responses. The neocortex is the home of rationality – conscious, deliberate thinking.

- Procedural memory combines bottom-up and top-down processing to help us solve routine and familiar problems by ‘patterning in’ complex actions.

- Emotions trigger responses to situations that threaten us or promise some advantage – responses that we can sometimes moderate using rational thought.

- The stress responses, both short-term and long-term, can help us perform better as problem-solvers but can also do us serious harm.

- Reasoning helps us construct arguments and reach conclusions.

- Our multiple intelligences serve us well as problem-solving specialists.

- Cognitive fluidity gives us the imagination to look at problems in new ways and combine intelligences to generate innovative solutions.

And how do we navigate all these different levels and types of faculty? By means of language.