8

Your NewSmart Behaviors Assessment Tool

In chapters 4–7 we presented the four NewSmart Behaviors that we believe underlie the higher-level thinking and emotional engagement skills that humans will need to master in order to thrive in the SMA. Here we present a tool for you to assess your strengths and weaknesses with respect to those NewSmart Behaviors. The assessment reflects that each behavior requires you to excel at many different sub-behaviors or component behavioral parts. For example, Reflective Listening includes paying attention to a speaker’s body language and not interrupting. The assessment asks how often you engage in these various sub-behaviors on a scale of 1 to 5. For most questions, the higher your score, the better you’re doing; however, for some questions the opposite is true. We learned from experience that adding these reversed types of questions (which we’ve marked with an asterisk) slows people down and gives them time to reflect before grading themselves, making their scores more realistic.

Note that because of this varied rating scale, you cannot easily add up your numbers for a total or average NewSmart Behaviors score. We did that because an average or total score could mask significant sub-behavior weaknesses. Our message is that you have to excel at many sub-behaviors in order to excel at the big behavior. An average or total score won’t help you do that. Ed has used this diagnostic with several hundred people in his teaching and consulting. We’re sharing it here because many of those people found it helpful in assessing their weaknesses and in creating a NewSmart Behaviors Personal Improvement Plan.

Please note that this is only a tool—it has not been statistically validated. The tool’s purpose is to provide you with information, and it’ll be useful to you only if you’re totally honest about assessing yourself. To get a realistic picture, some people have found it helpful to have other trusted people also assess them. Ed has also learned from experience that many people decide to retake the diagnostic after the first attempt because they realize that they weren’t brutally honest with themselves the first time through. How do you know if you’re being brutally honest? See if you gave yourself a lot of 4s and 5s the first time around (and 1s and 2s for the questions with an asterisk). Were those scores really justified?

Following the assessment are some instructions for reflecting on your results. You’re asked to state what you’ve learned. You may find that you have lots of areas that need improvement. Most people do because few of us have ever had any formal training on these behaviors. That’s right: few of us have had formal training on how to excel at the key NewSmart Behaviors, so don’t get discouraged if you need to improve on all of them. We have also learned that many of those who have had some training on a particular behavior don’t necessarily practice the behaviors as much as they think. There’s often a big gap between what we know and what we actually do.

1. Quieting Ego

1 = Never 2 = Very Rarely 3 = Infrequently 4 = Sometimes 5 = Regularly

I actively try every day to quiet my ego.

I’m aware when I’m becoming very “me” oriented.

I evaluate my level of Humility daily and whether I was arrogant or “all about me.”

I believe that “I’m not my ideas.”

I understand that “it’s not all about me.”

I like telling people about my accomplishments.*

I like being the center of attention.*

I tend to dominate conversations.*

I have been told that I’m arrogant.*

Work colleagues would say that I know my weaknesses.

I often say: “I don’t know.”

When I act badly at work, I apologize to that person (in public if the act occurred in public).

I take ownership publicly of my mistakes.

I’m open about my weaknesses and ask people at work for help.

I believe that I’m special and better than many people.*

I react defensively when someone disagrees with me.*

I think a lot about whether people think I’m smart.*

I think a lot about how I’m perceived.*

I avoid situations where I may not look good.*

In a conversation, I want the other person to leave thinking I’m smart.*

I frequently put myself emotionally into another person’s shoes.

I believe that leaders must be strong and not show weakness.*

I’m sensitive to when I’m getting defensive.

I must leave each engagement winning.* I use mindfulness to quiet my ego.

I’m compassionate with others.

I accept that I’m a suboptimal thinker and listener.

I seek praise.*

I seek negative feedback.

2(a). Managing Self (Thinking)

1 = Never 2 = Very Rarely 3 = Infrequently 4 = Sometimes 5 = Regularly

I’m open-minded.

I’m fair-minded.

I’m mindful—really present in the moment with my full attention.

Frequently during the day I slow myself down to think deeply. I use data to make my decisions.

I’m very curious.

I’m good at not knowing—I frequently say “I don’t know.”

What is right is more important to me than who is right.

I’m paranoid about missing something and about being overconfident.

I confront the brutal facts—even if they make me look bad.

I approach having difficult conversations; I don’t avoid them.

I exhibit intellectual humility in my interactions with everyone.

I have learned to decouple my ego from my beliefs.

I actively manage my thinking daily.

I’m aware of when I need to slow down to think.

I use good thinking processes daily.

I use good collaborating processes daily.

I grade myself daily and keep a learning journal.

I have a checklist of my “needs to improve.”

I share my “needs to improve” with teammates and ask them to help me improve.

I role-model humility, including intellectual humility.

I role-model learning resiliency—bouncing back quickly from mistakes and failures.

I critique ideas, not people.

I give all my associates the permission to speak freely.

I reward candor.

I’m honest and transparent about my weaknesses and mistakes.

I actively seek constructive feedback about my thinking from others.

I unpack the assumptions underlying my thoughts daily.

I seek to stress-test some of my thoughts or beliefs daily.

I evaluate the results of my decisions and lessons learned.

I worry about my biases.

I have devised ways to mitigate my biases.

I use mental rehearsal daily to play things out in my mind.

I use mental replay daily to reflect on my actions and decisions in order to learn.

At least two times a week, I tell a peer or employee: “I don’t know.”

At least two times a week, I ask a peer or employee to critique my thinking.

I ask my direct reports monthly to give me candid feedback on my performance.

I tell myself daily that I have to think deeper about an issue.

2(b). Managing Self (Emotions)

1 = Never 2 = Very Rarely 3 = Infrequently 4 = Sometimes 5 = Regularly

I’m very sensitive to my emotions.

I label my emotions.

I try to understand why I’m feeling what I feel.

I actively choose whether to engage with an emotion or let it pass.

I know when I’m feeling defensive or fearful.

I actively manage my fears.

I understand what makes me feel fearful.

I frequently take deep breaths to calm myself.

I frequently think about something positive in my life to reduce my fear.

I’m sensitive to my body language.

I’m sensitive to how others are receiving my message.

I’m sensitive to others’ emotions.

I’m sensitive to others’ body language and tone.

I take others’ emotions into account when conversing.

I try to approach meetings and others with a positive emotional state.

I use deep breaths to manage my emotions.

I try to put myself in a positive emotional state before thinking deeply about something.

I actively try to manage my emotions.

I know how to and frequently prevent my emotions from hijacking my thinking.

3. Reflective Listening

1 = Never 2 = Very Rarely 3 = Infrequently 4 = Sometimes 5 = Regularly

I’m a nonjudgmental listener.

I’m a nondefensive listener.

When I listen, I focus on whether the speaker agrees with me.*

I often get bored listening to others, so my mind wanders.*

I interrupt people when I know the answer.*

I often paraphrase and repeat back what I think the speaker is saying, and ask if I’m hearing him or her correctly.

If I don’t understand, I often ask the speaker to say it a different way.

I apologize when I interrupt someone speaking to me.

I begin formulating my answer/response in my head while someone is talking.*

While listening, I’m aware of my body reactions.

I finish people’s sentences out loud or in my head.*

As I listen, I try to make eye contact with the speaker.

As I listen, I’m aware of my emotions.

Before engaging in an important conversation, I ask myself if I’m ready to be open-minded.

Before engaging in an important conversation, I calm my emotions.

I usually don’t answer quickly; I reflect.

While listening, I’m sensitive to the speaker’s emotions, tone, and body language.

In difficult conversations, before responding, I thank the speaker for having the courage to talk.

I often assume that I know what the speaker will say next.*

I often ask questions intended to confirm my view.*

I often ask questions that will lead the speaker toward my view.*

When listening, I pause to “try on” the person’s ideas or beliefs to see how it feels.

I listen to learn, not to confirm.

I multitask when I listen.*

I multitask when I talk on the phone.*

I multitask when I attend meetings virtually.*

4. Otherness (Emotionally Connecting and Relating)

1 = Never 2 = Very Rarely 3 = Infrequently 4 = Sometimes 5 = Regularly

I know my EI weaknesses and have a plan to improve them.

I relate personally to people before getting to business.

I try to demonstrate to people that I care about them.

I try to understand where people are coming from.

I try to be an emotionally positive person.

I try to be totally honest with people.

I evaluate the quality of my emotional connections daily.

I’m sensitive to the messages I send through my body language.

I stop and make sure before I enter each meeting that I’m emotionally and mentally prepared to be present—to be fully attentive in that meeting.

I view collaboration as a competition to see who is right.*

My goal in collaborating is to avoid looking dumb.*

Another goal in collaboration is to not “lose face.”*

I stop regularly to engage with people during the day.

I do “check-ins” with my direct reports and ask about them as people.

I ask people at the end of a meeting whether they’re in a “good place.”

In collaborating, I try to inquire as much as I advocate.

In collaborating, I act as if what is accurate is more important than who is right.

In collaborating, I focus on what is wrong, not who is wrong. In collaborating, I’m mindful of who is not engaged.

In collaborating, I seek to engage the quiet ones.

In collaborating, I’m mindful of the “elephant in the room.”

In collaborating, I often will raise the hard issue or talk about the “elephant.”

In collaborating, if I don’t know, I say so.

In collaborating, I’m mindful of my body reactions and body language.

I’m aware when I react defensively.

I usually tell people what to do or how to do it.* I go out of my way to show gratitude to people.

Every day I ask people with whom I work how they’re doing, and I show them that I care about their answers.

I smile at people.

I slow down and connect—even for a short time.

I’m direct, courteous, and honest with others.

I keep my word and my commitments.

I’m authentic with others.

I engender trust by taking the first step to be vulnerable.

I focus on others when conversing with them.

I truly try to get to know others deeply so I can understand them.

I don’t gossip about others.

I keep in confidence things said to me in confidence.

I keep in confidence things said to me by others when they’re being courageously vulnerable.

I thank people for having the courage to challenge my ideas.

What Did I Learn from My Diagnostic?

Now you’re ready to review and make meaning of your results. Go slowly, line by line (that is, sub-behavior by sub-behavior). Focus on those statements for which you gave yourself a low grade. What do your results “say” to you? What are the sub-behaviors that you need to work on? We recommend that you make a list of those sub-behaviors.

Now what?

Step 1: Prioritize the behaviors and sub-behaviors

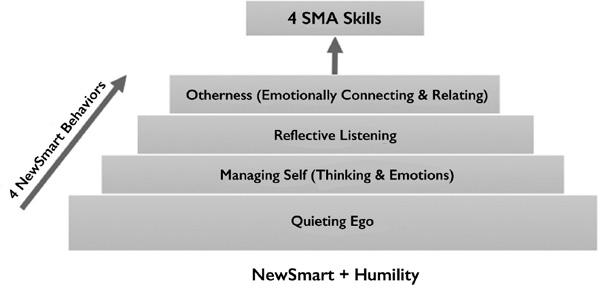

We suggest starting with the NewSmart Behavior that’s the lowest on the NewSmart Behavior pyramid shown below. Although the behaviors overlap in many ways and reinforce each other, we find that it’s easier for many people to think about them building on each other from the bottom up. For example, if you scored poorly on Quieting Ego and Reflective Listening, start with Quieting Ego. Then, look at your list of underlying sub-behaviors that need improving. Pick one or two sub-behaviors on which you scored poorly.

Step 2: Talk it out

After picking your sub-behaviors, have conversations with other people you trust about the behaviors you want to improve and why you want to improve them. Ask people to be on the watch for how you’re doing and ask them to give you feedback. Ask for their support and encouragement. Talking about why you want to change a behavior helps you “make meaning” of the information and can create more of a commitment to change. If you’re seeking to curb a bad behavior, try to figure out why you’re behaving that way and how you are benefiting from the bad behavior. Talk about this with a trusted other. We have found that figuring out the “why” is also much easier if you talk it out with someone.

Step 3: Learn the science of improving

One purpose of this book is to invite you to take your thinking, listening, relating, and collaborating skills to a much higher level in order to excel and even become an expert. Some of the best work and research on achieving high mental performance comes from Lyle Bourne and Alice Healy of the University of Colorado in Train Your Mind for Peak Performance and from Anders Ericsson of Florida State University in PEAK: Secrets from the New Science of Expertise. The work of these experts emphasizes the importance of having the discipline to practice daily; the importance of real-time feedback; and the importance of “deliberate” practice, which is practice focused on improving in a certain way specific behaviors or parts of behaviors that underlie a skill.

What does this mean for you in this context? To become expert at NewSmart Behaviors requires self-discipline, high motivation, perseverance, and practice, practice, practice. Training and deliberate practice are specific to the particular skill. For example, not interrupting is a necessary sub-behavior of Reflective Listening, but alone it’s not sufficient to excel at this crucial NewSmart Behavior. To excel may require improvement in many other sub-behaviors of Reflective Listening.

How you practice is also important—the key is to do it deliberately by breaking down the desired behavior into its component parts. That’s why we focus on sub-behaviors. Let’s assume, for example, that many of you, like almost all the several hundred people to whom Ed has given the NewSmart Behaviors Assessment over the past few years, determined that you need to improve your Reflective Listening. Unfortunately, you can’t just start practicing Reflective Listening. Instead, you need to isolate specific parts of Reflective Listening that you want to improve. The tools and content in chapters 4–7 can be helpful in delineating those component parts.

Let’s assume that you determined you need to be mindfully present and open-minded when you enter a conversation and that you need to stop interrupting people and ask questions to make sure you understand what the other person just said before advocating or telling her or him your view. Think about those three component behaviors logically. Which makes sense to work on first? It would seem to us that you have to be mindfully present and open-minded to do the other two behaviors.

Step 4: Get advice from an “expert”

Do you know individuals who are good at Reflective Listening? Are you comfortable seeking advice from them? Tell them that you respect the way they listen to others and that you’re trying to be a better listener. Ask them how they stay focused and, for example, how they refrain from formulating their answers while other people are talking. Ask them how they learned to ask questions before responding. How do they self-monitor themselves? What advice do they have about “how to” be mindfully present and open-minded?

Step 5: Create your experiment

Let’s assume that to improve your Reflective Listening you’ve decided to work first on being mindfully present to listen with an open mind. How do you do that? You may want to refer to chapter 6 for some ideas. Assume that you decide to use the premeeting guide from chapter 6 that prepares you to be mindful and emotionally positive. OK, so, your first experiment is to prepare before each conversation to be mindfully present and to stay focused on the speaker and his or her words, listening to understand what he or she is saying before thinking about your response.

Step 6: “Warm up”

Continuing with the example in step 5, you could do the following: before each conversation, take four deep breaths, counting to four on the inhale and again on the exhale. Think of something or someone who evokes strong positive feelings for you—maybe a loved one, your pet, a dear friend, or someone who did a nice thing for you. Then repeat these sentences: “I am not my ideas,” “My mental models are not reality,” “This is not all about me,” and “Listen to learn, not to confirm.”

Now mentally visualize how you’ll behave and how it’ll feel. Think about how you’ll sit. What posture relaxes you? Think about the position of your hands—open or closed? Think about smiling often. Think about maintaining eye contact with the speaker. See yourself sitting calmly in the meeting really focused with all your being on listening. See yourself bringing your attention back to the present if your mind wanders or if you begin to formulate your response while the person is talking. Rehearse in your mind what you’ll do if you begin to lose your focus in the meeting. For example, perhaps you’ll tell yourself “come back to listening” or “let that thought pass or float on by.”

Step 7: Deliberately practice

Now engage in those behaviors every opportunity you have today and tomorrow and the next day, and the next. Remember that knowing what to do is not the same as doing it consistently and excellently. Building new habits requires motivation, focus, and repetition.

Step 8: Measure yourself

Continuing with our experiment, now is the time to measure your progress. At the end of the particular conversation, take a few minutes and mentally replay it in your head and grade yourself. How many times did you daydream? How many times did you create your response in your head while the other person was talking? How many times did you think about some other matter? How many times did you recognize that you were losing focus and bring back your attention? Keep a record. Write down your self-feedback. What steps did you do well? Record your results and track your results daily and monthly.

Soon thereafter, think about the times you were not mindfully present. What were you doing instead? Is there a pattern? Try to recall how you felt then. Were you bored? Worried about your next meeting? Feeling defensive? Feeling what? Trying to understand when you lose focus or why may help create an early warning system that alerts you when to work even harder on focusing.

Grade yourself in every meeting for a few days and talk frequently with your trusted others who are monitoring your progress. Perhaps you’re making progress on a few items, but not making as much progress on, say, not formulating your response while the speaker is still talking. You could then focus more on mentally rehearsing and preparing yourself before each meeting to “listen to understand” and ask questions to make sure that you understand what the person is saying before you respond. Feel good about the progress you make. It will come at different speeds for different sub-behaviors. But stay disciplined. It could really help to get feedback from trusted others who observe you in the meetings. Many of us go mindlessly from meeting to meeting. Plan for a five-minute break between meetings for reflection and grading or at least reflect while you walk to the next meeting.

If your plan isn’t working, go back to the expert and seek advice. Ask other excellent listeners how they do the specific behavior. Don’t give up. Try something new and keep working at it until you make progress. Remember, we’re not talking about creating an Einstein formula, we’re talking about managing how you listen. You may have to try several different approaches—the key is to keep working at it. What have we found in our work with others? Too many people lack the self-discipline to work at this. And those who do work hard see positive results at work and in their personal lives, which further motivates them to keep working.

Step 9: Be patient, savor small improvements, and persevere

One lesson we have learned from our research is that people who are very good at thinking, listening, relating, and managing their thinking and emotions never take it for granted. They stay focused on it daily by using processes, checklists, templates, and feedback. They are constructively paranoid about slippage and reverting to our natural proclivities of lazy thinking and emotional defensiveness. They understand that it requires motivation to excel and self-discipline to work daily on improving themselves.

You will make mistakes. Learn from them and stay the course. Take it one day at a time. You’ll never reach perfection, but you can incrementally improve. You’ll be trying to reverse decades of habits. It won’t happen quickly, but progress can be made. Striving to reach your highest potential is a never-ending process that can be a meaningful learning journey in itself.

I (Ed) will give you an example of my long and winding journey to improve my Reflective Listening abilities. As I’ve said, I realized that I wasn’t a good listener because I often interrupted people in conversations and meetings. I wanted to stop that behavior, so I decided that I’d wait until a person stopped talking and then count to ten before I spoke. That didn’t work. Then I decided that I would put the heel of my right foot on the instep of my left foot and press down hard if I started to interrupt someone. That also didn’t work, but it did hurt a lot.

I realized that I needed some additional help and reached out to a close friend who happened to be the colleague of Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey, the authors of Immunity to Change. In their book Kegan and Lahey explained that most people behave the way they do because it produces some favorable result. As such, it’s hard to change those behaviors unless you unpack the reasons why you behave that way and then deal with the underlying belief.1

In two hourlong telephone calls with my friend, I finally got to the nub: I interrupted people because I believed it resulted in looking smart (not arrogant, inconsiderate, and rude). Deep down I believed that if I didn’t get the right answer before someone else spoke, then other people wouldn’t think I was that competent. That was my big assumption. To change that behavior, then, I had to run an experiment—if I didn’t interrupt people and they still thought that I was competent, then my assumption would be proved false and I could more easily change this behavior.

So I committed to not interrupting people in meetings and then sought feedback on my new behavior. Turned out that no one thought I wasn’t competent simply because I listened and tried to understand others before advocating my position. In fact, some people said that they thought the new behavior made me more effective in meetings and that they liked the fact that I had stopped being a rude person who interrupted. I share this story because it demonstrates that changing behaviors can be hard and may require unpacking the reasons that you behave the way you do and changing your mental model about that behavior.