CHAPTER TWO

THREE LEVELS OF PERFORMANCE: ORGANIZATION, PROCESS, AND JOB/PERFORMER

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.

—JOHN MUIR

Nineteenth-century environmentalist John Muir found that each component of the ecosystem is in some way connected to all other components. The brouhaha over the snail darter, which ultimately halted construction on the Clinch River breeder reactor, was not just about a tiny fish that affects very few of us; it was about tampering with a small tile in the environmental mosaic. Each tile that is removed or changed alters, if only in a minute way, the balance of the picture.

Similarly, we have found that everything in an organization’s internal and external “ecosystem” (customers, products and services, reward systems, technology, organization structure, and so on) is connected. To improve organization and individual performance, we need to understand these connections. The current mosaic may not present a very pretty picture, but it is a picture. The picture can be changed or enhanced only through a holistic approach that recognizes the interdependence of the Nine Performance Variables. We have found that the way to understand these variables is through the application of the systems view (described in Chapter One) to Three Levels of Performance.

I: The Organization Level

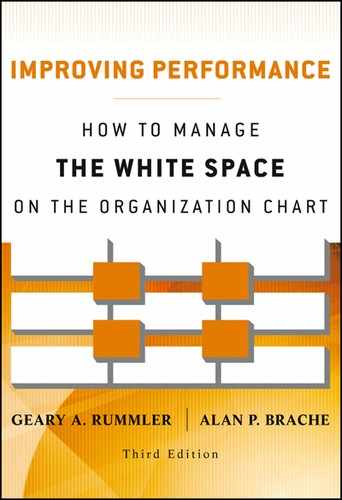

When we take our first, macro “systems” look at the organization, we see the fundamental view and variables discussed in Chapter Two. This level—the Organization Level—emphasizes the organization’s relationship with its market and the basic “skeleton” of the major functions that comprise the organization. Variables at Level I that affect performance include strategies, organizationwide goals and measures, organization structure, and deployment of resources (see Figure 2.1).

FIGURE 2.1. THE ORGANIZATION LEVEL OF PERFORMANCE

II: The Process Level

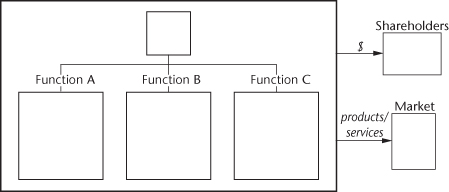

The next set of critical variables affecting an organization’s performance is at what we call the Process Level. If we were to put our organization “body” under a special x-ray, we would see both the skeleton of Level I and the musculature of the cross-functional processes that make up Level II (see Figure 2.2).

FIGURE 2.2. THE PROCESS LEVEL OF PERFORMANCE

When we look beyond the functional boundaries that make up the organization chart, we can see the work flow—how the work gets done. We contend that organizations produce their outputs through myriad cross-functional work processes, such as the new-product design process, the merchandising process, the production process, the sales process, the distribution process, and the billing process (to name a very few).

An organization is only as good as its processes. To manage the Performance Variables at the Process Level, one must ensure that processes are installed to meet customer needs, that those processes work effectively and efficiently, and that the process goals and measures are driven by the customers’ and the organization’s requirements.

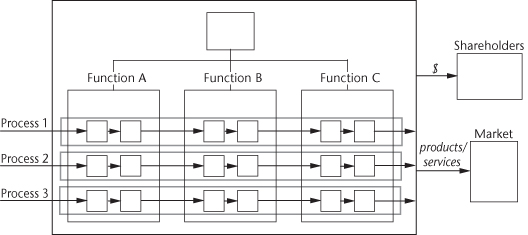

III: The Job/Performer Level

Organization outputs are produced through processes. Processes, in turn, are performed and managed by individuals doing various jobs. If we increase the power of our x-ray, as in Figure 2.3, we can see this third Level of Performance, which represents the cells of the body. The Performance Variables that must be managed at the Job/Performer Level include hiring and promotion, job responsibilities and standards, feedback, rewards, and training.

FIGURE 2.3. THE JOB/PERFORMER LEVEL OF PERFORMANCE

Now we have an organization x-ray that depicts the three critical interdependent Levels of Performance. The overall performance of an organization (how well it meets the expectations of its customers) is the result of goals, structures, and management actions at all Three Levels of Performance. If a customer receives a shipment of faulty framuses, for example, the cause may lie in any or all of the Three Levels. The performer may have assembled the framuses incorrectly and/or let faulty framuses be shipped. The processes that influence framus quality (including design, procurement, production, and distribution) may be at fault. The organization—represented by top managers who determine the role of framuses in the organization strategy, provide the budgets for staff and equipment, and establish the goals and measures—may also have caused the problem.

Assembly performers can be trained in statistical process control techniques, can be grouped into self-managed work teams, and can be empowered to stop the line if they encounter defects. However, those actions will have little effect if the design process has produced a framus that is difficult to assemble correctly, or if the purchasing process can’t acquire enough subassemblies, or if out-of-sync sales and forecasting processes lead to product changeovers that require the assembler to follow a different procedure every day. The desire of the assembler to produce a high-quality framus will be further compromised if, in this organization, the primary measure and basis of rewards is “the number of units shipped.”

The Three Levels framework represents an anatomy of performance. The anatomy of the human body includes a skeletal system, a muscular system, and a central nervous system. Since all of these systems are critical and interdependent, a failure in one subsystem affects the ability of the body to perform effectively. Just as an understanding of human anatomy is fundamental to a doctor’s diagnosis and treatment of ailments in a body, an understanding of the Three Levels of Performance is fundamental to a manager’s or analyst’s diagnosis and treatment of ailments in an organization.

However, our focus is not only on curing such ailments. Just as enlightened members of the medical community use their knowledge of human anatomy to promote wellness and preventive medicine, enlightened members of the management community use their knowledge of performance anatomy to prevent organization problems and continuously improve performance. But they can’t do it alone. These managers use the talents of their human resource, systems, and management analysts in the same way that veteran doctors benefit from the contributions of their interns, nurses, and laboratory staff.

In Chapter Seven, we describe four performance improvement efforts that are flawed by their failure to address one or more of the Three Levels of Performance. We then present two examples of organizations that have successfully implemented improvement efforts, which included action at all Three Levels.

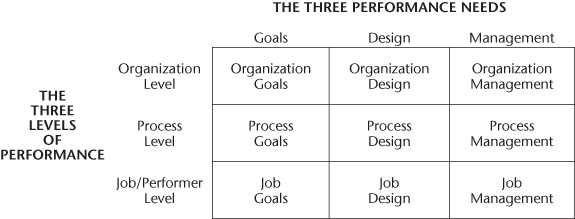

The Nine Performance Variables

The Three Levels of Performance constitute one dimension of our framework. The second dimension comprises three factors—Performance Needs—that determine effectiveness at each level (and the effectiveness of any system):

Combining the Three Levels with the Performance Needs results in the Nine Performance Variables. These variables, which appear in Table 2.1, represent a comprehensive set of improvement levers that can be used by managers at any level.

TABLE 2.1. THE NINE PERFORMANCE VARIABLES

To illustrate the Three Levels approach, let’s take a brief look at the company that we introduced in Chapter One. To refresh your memory, Computec, Inc., is a software development and systems engineering firm, with 70 percent of its business from custom software development and consulting services. The other 30 percent of revenues is generated by off-the-shelf software packages.

Computec was successful for the first thirteen years of its existence. However, during the past two years, it has experienced significant erosion of its market share. Internal problems include high turnover and sinking morale. Senior management is concerned about the situation and has recently studied the organization culture and completed programs on total quality, customer focus, and entrepreneurship. The next program is slated to be on reengineering. So far, company performance has not improved.

Realizing that previous medication may or may not have attacked the disease, we begin by diagnosing Computec. We will use the Nine Performance Variables that make up the framework of the Three Levels approach.

Organization Level

Before we can effectively analyze the human dimensions of performance, we need to establish a macro-level context. At the Organization Level, we examine the nature and direction of the business and the way it is set up and managed. (In Chapter Three, we will present the specific tools; the following is a discussion of the three Performance Variables at the Organization Level.)

Organization Goals. At the Organization Level, goals are part of the business strategy. All Three Levels and all of the other Performance Variables build on the direction established by the Organization Goals. In this example, our primary question is whether Computec has established clear companywide goals that reflect decisions regarding (1) the organization’s competitive advantage(s), (2) new services and new markets, (3) the emphasis it will place on its various products or services and markets, and (4) the resources it is prepared to invest in its operations and the return it expects to realize on these investments. Through this line of questioning, we find that Computec has not established a clear strategy.

Because the company dominated its historic market niche (aerospace project management) until two years ago, top management never spent much time investigating strategic alternatives and preparing for the current competitive environment. The executive team has recently realized the need for a strategy and a set of companywide goals derived from that strategy. While the executives have much more work to do in this area, they have established three clear goals: to aggressively develop new products and services, to provide a level of customer support that differentiates Computec from its competition, and to eliminate the company’s competitive disadvantage in the quality and timeliness of filling its orders for standard software products. While these goals are not yet measurable, they provide guidance to employees who otherwise might think that Computec is banking on growth from its existing products, does not intend to feature customer service, and intends to emphasize price (rather than quality and timeliness) as its competitive advantage.

Organization Design. This variable focuses on the structure of the organization. However, our systems view of performance suggests that “structure” should include more than where departmental boundaries have been drawn and who reports to whom. Structure includes the more important dimension of how the work gets done and whether it makes sense. We would begin by developing a Relationship Map, which shows the interfaces among the Computec functions. (The Computec organization chart and Relationship Map appear in Chapter Three.)

We have two key questions: Does Computec have all of the functional components it needs to achieve its strategy? Should any input-output connections (supplier-customer relationships) be added, eliminated, or altered?

Although Computec has occasionally introduced new services, few have been successful. The company relies on two packaged software products and three services, all of which it developed early in its history. The organization structure does not support speedy, effective new-product development and introduction, postsale customer support, or order processing. Given Computec’s Organization Goals, the organization structure will have to be realigned to support these three areas of strategic emphasis.

Organization Management. An organization may have appropriate goals and a structure that enables it to function as an efficient system. However, to operate effectively and efficiently, the organization must be managed. At the Organization Level, management includes:

The Organization Management question is this: Is the Computec executive team managing goals, performance, resources, and interfaces?

Computec is not doing well in this area. Many of its functional goals are in conflict and support short-term profit, rather than the strategic goals around product development, customer service, and order processing. The company has no system for performance tracking, feedback, and improvement. Resources are allocated on a “whoever shouts loudest” basis, and the silos around product development, marketing, and operations are tall and well fortified. All four Organization Management areas will have to be addressed if Computec’s strategy is to succeed.

Process Level

When we lift the lid and peer inside an organization, the first things we see are the various functions. However, the systems view suggests that this perspective does not enable us to understand the way work actually gets done, which is a necessary precursor to performance improvement. For this understanding, we need to look at processes. Most key dimensions of organization performance result from cross-functional processes, such as order handling, billing, procurement, product development, customer service, and sales forecasting. Chapter Four more fully explores the Process Level; the following is an overview of its three Variables, using Computec as an example.

Process Goals. Since processes are the vehicle through which work gets produced, we need to set goals for processes. The goals for processes that touch the external customer (for example, sales, service, and billing) should be derived from the Organization Goals and other customer requirements. The goals for internal processes (for example, planning, budgeting, and recruiting) should be driven by the needs of the internal customers.

Functional goals, which are part of the Organization Management variable just discussed, should not be finalized until we see the contribution that each function needs to make to the key processes. Each function exists to serve the needs of one or more internal or external customers. If a function serves external customers, it should be measured on the degree to which its products and services meet those customers’ needs. If a function serves only internal customers, it should be measured on the way it meets those customers’ needs and on the value it ultimately adds to the external customer. In both cases, the key links to the customer are the processes to which the function contributes.

The installation process, for example, is critical to any company that installs equipment in a business or a residence. One function that contributes to the installation process is the sales department. Even though sales may not be part of the installation itself, it is part of the installation process because salespeople usually write orders that include specifications for equipment installations. Because it has a significant impact on the quality and timeliness of an installation, the sales department should be measured on the accuracy, specificity, understandability, and timeliness with which its people provide installation specifications to the department that performs the installation. Installation specification goals are not necessarily part of the sales measurement system. However, when you look at the organization as a set of processes, and at the sales department in terms of the contributions it makes to all the processes it supports, a richer set of goals emerges.

For our overview of Computec’s performance in terms of Process Goals, we have two primary questions: Does the company have goals for its processes (particularly those cross-functional processes that influence the strategy)? Are the Process Goals linked to customers’ requirements and to the Organization Goals?

Given Computec’s strategic thrusts and vulnerabilities, its key processes are the product or service development process, the customer support process, and the order-filling process (for its off-the-shelf software). Not surprisingly, Computec has no goals for these processes. Furthermore, its functional goals do not support the optimal performance of these processes.

Process Design. Once we have Process Goals, we need to make sure that our processes are structured (designed) to meet the goals efficiently. Processes should be logical, streamlined paths to the achievement of the goals. As part of our Computec analysis, we have one simple question that addresses this variable: Do the company’s key processes consist of steps that enable it to meet Process Goals efficiently?

Earlier, we determined that Computec has no Process Goals. However, we can still examine its three key processes. The mechanism for product development and introduction is not really a process, by anyone’s definition of the term. Products and services eventually emerge from poorly coordinated projects, which are characterized by functional bickering, budget overruns, missed deadlines, and lack of ownership. When the order-filling process is analyzed, the only surprise is that Computec does occasionally meet customers’ expectations for quality and timeliness. A customer support process has never really been created. This company has a lot of work to do in the process area. (Examples of Computec processes appear in Chapter Four.)

Process Management. A process with a logical structure will be ineffective if it is not managed. Process Management includes the same ingredients as Organization Management:

Does Computec manage the goals, performance, resources, and interfaces of its key processes? Since Computec has not established a cross-functional orientation to its business, it has not established a Process Management infrastructure for its key processes.

Job/Performer Level

The Organization and Process Levels may be beautifully wired in terms of goals, design, and management. However, the electricity will flow only if we address the needs of the people who make or break organization and process performance. If processes are the vehicles through which an organization produces its outputs, people are the vehicles through which processes function. (We address the human dimension of performance through the Job/Performer Level, which is covered in depth in Chapter Five.)

Job Goals. Just as we need to establish Process Goals that support Organization Goals, we need to establish goals for the people in those jobs that support the processes. In examining Computec, we ask what jobs contribute to each key business process, and whether the outputs and standards (goals) of these jobs are linked to the requirements of the key business processes (which are in turn linked to customer and organization requirements).

One of Computec’s key processes is the off-the-shelf software order-filling process. A variety of jobs in the sales, production, and finance functions contribute to this process. Like most companies, Computec is not doing a good job of goal setting at the Job/Performer Level. The Job Goals that have been set have not been tied to process requirements. Computec needs to establish process-driven goals for each job in the functions just listed. If the company does not take this step, the odds of achieving the strategic (Organization Level) goals are low.

Job Design. We need to design jobs so that they make the optimum contribution to the Job Goals. The Job Design question is a simple one: Has Computec structured the boundaries and responsibilities of its jobs so that they enable the Job Goals to be met? Again, Computec has never looked at its business through the eyes of Organization, Process, and Job Goals, and so it has never used that perspective as the basis for structuring jobs.

Job Management. The list of ingredients in Job Management does not fall into the goals, performance, resources, and interfaces categories we used when discussing the variables of Organization Management and Process Management. Job Management is really people management. However, this definition supports managers’ tendency to overmanage individuals and undermanage the environment in which they work. Therefore, Job Management is more accurately defined as managing the Human Performance System.

While it may sound as if this approach dehumanizes the management of people, the effect is quite the contrary. Human Performance System management is based on the premise that people, for the most part, are motivated and talented. If they don’t perform optimally, the cause is most likely in the system (at the Organization, Process, and/or Job/Performer Level) in which they’ve been asked to perform. The Human Performance System, like the organization system, is composed of inputs, processes, outputs, and feedback, all of which need to be managed.

If Computec is effectively managing the Human Performance System of its key jobs, the managers and incumbents in those jobs would answer yes to these questions:

If Computec is to be successful, its managers must create a supportive environment around the people who will determine whether the company strategy becomes reality. For example, one of Computec’s Organization Goals is to improve its customer service to the point that it becomes a competitive advantage. Its customer service hotline is currently staffed on a rotating basis by the field operations people, who consider phone duty punishing, believe it takes them away from their real jobs, and do not have the skills to handle customers’ complaints effectively and efficiently. If customer service is to be a competitive advantage, then the needs related to Task Support, Consequences, and Skills and Knowledge will have to be addressed.

A Holistic View of Performance

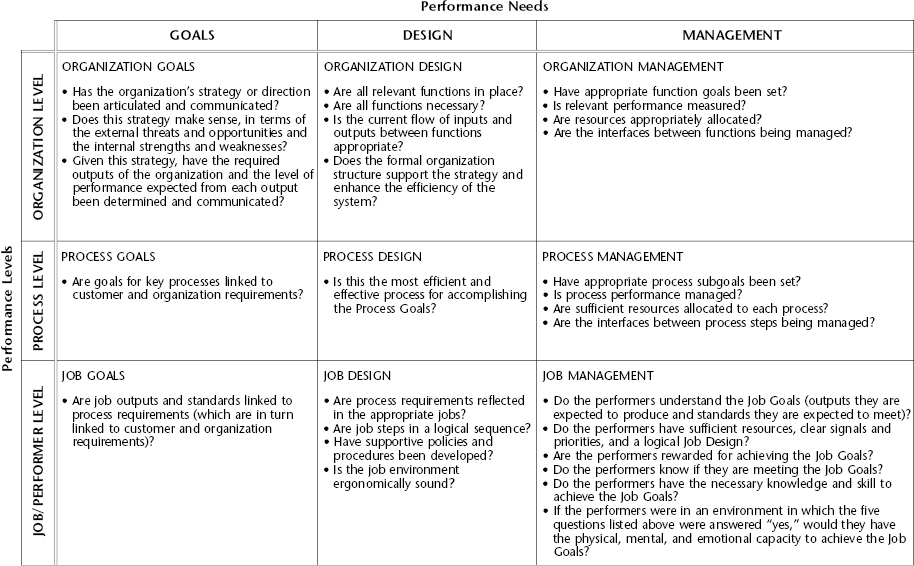

Table 2.2 shows the questions associated with each of the Nine Performance Variables in our framework. This systems view of performance has led us to two conclusions:

- Effective management of performance requires goal setting, designing, and managing each of the Three Levels of Performance—the Organization Level, the Process Level, and the Job/Performer Level.

- The Three Levels are interdependent. For example, a job cannot be properly defined by someone who doesn’t understand the requirements of the business process(es) that the job exists to support. Any attempt to implement Organization Goals will fail if those goals are not supported by processes and Human Performance Systems.

TABLE 2.2. THE NINE PERFORMANCE VARIABLES WITH QUESTIONS

The Three Levels framework provides some insight into the shortcomings of many attempts to change and improve organizations. For example:

- Most training attempts to improve organization and process performance by addressing only one Level (the Job/Performer Level) and only one dimension of the Job/Performer Level (skills and knowledge). As a result, the training has no significant long-term impact, training dollars are wasted, and trainees are frustrated and confused.

- Automation is generally an attempt to improve the performance of the Process Level. However, the investment in automation rarely realizes its maximum return because the link is not made between the process and the Organization Goals to which it is intended to contribute: the process is inefficient, and so the result is an automated inefficient process; and the automation fails to consider the needs of the Human Performance Systems of the people involved in the process.

- If programs to improve performance in such areas as quality, productivity, and customer focus are just hype, they don’t address the needs of any of the Three Levels. Programs that establish Organization Goals and train employees usually fail to address the needs at the Process Level and the goals, feedback, and consequences required at the Job Level.

Using the Three Levels Framework

This framework (summarized in Table 2.2), as well as the process and tools that it has spawned, has evolved over twenty years of research and application in companies, agencies, divisions, departments, and stores. It has been used as:

- A tool for diagnosing and eliminating deficient performance (for example, excessive semiconductor chip manufacturing and delivery cycle time; loss of margins in a retail chain)

- An engine for continuously improving systems that are performing adequately (for example, increasing responsiveness to airlines’ needs for unique aircraft configurations; increasing timeliness of telecommunications customer service)

- A road map for guiding an organization in a new direction (for example, toward entering the software business or selling in a newly deregulated environment)

- A blueprint for designing a new entity (for example, an electronics “factory of the future”; a marketing department in a public utility)

The Three Levels framework has proved valuable to:

- Executives, who provide the vision, leadership, and impetus for change

- Managers at all levels, who implement companywide changes by providing vision and leadership on the Organization Level for the departments they manage

- Analysts, who design the systems and procedures that enable managers to implement the change

For all three of these forces of change to work efficiently in concert, they must have the same objectives and process. The Three Levels of Performance framework has been designed to meet this need. The remainder of this book addresses the performance improvement responsibilities of all three roles.