CHAPTER EIGHT

DIAGNOSING AND IMPROVING PERFORMANCE: A CASE STUDY

Medicine, to produce health, has to examine disease.

—PLUTARCH

The pharmaceutical industry has developed a host of effective medicines. Penicillin, for example, is a drug of demonstrated effectiveness. However, it probably won’t help a cataract. There’s no evidence that cortisone will do anything for a fever. Aspirin has been called a wonder drug, but it is actually harmful to someone suffering from an ulcer. Unfortunately, every effective medicine addresses only a limited number of ailments. Professional diagnosticians, called doctors, are paid to match medications with patients’ illnesses.

Similarly, there are lots of proven performance improvement “medicines” out there. Training is one form of medication. Reorganization is another. A management information system is another. An incentive compensation plan is yet another. The question is, Who are the “doctors” being paid to match these (and other) medications with our organizations’ illnesses?

Typically, the professionals who are paid to solve organization performance problems and to help capitalize on performance opportunities are in staff functions, such as human resource development (HRD), data processing (DP), and industrial engineering (IE). That’s fine. We cannot expect line managers to be masters of all of the possible performance improvement interventions. However, we have not, in general, carved out the appropriate roles for our staff people. They tend to be perceived (and, often, to perceive themselves) as providers of specific solutions. For example, the HRD folks provide training solutions, the DP people provide computer-systems solutions, and the IE mission is to provide work flow streamlining and ergonomic solutions.

Unlike diagnostically focused doctors, however, our staffers are frequently purveyors of their functions’ unique brands of patent medicine, claiming that their potions will cure what ails you. We believe that every staff analyst or consultant, regardless of the breadth of his or her “product line,” should be first of all a diagnostician. A dose of performance medication that does not address the disease is at best a waste of money. At worst, it causes side effects more serious than the original affliction.

Ideally, a line manager with a need would conduct a diagnosis and call in representatives of all the staff functions that can contribute to a comprehensive solution. However, we have found that a line manager generally does not have these skills, any more than a sick person has the ability to diagnose his or her own illness before calling in the appropriate specialist. Line managers have a feeling of pain or opportunity, and they know they need to take some action. However, in our experience, line managers rarely know what action they need to take to address a performance improvement opportunity. This reality puts the burden on staff people to diagnose situations before implementing solutions.

The Three Levels Approach to Performance Diagnosis and Improvement

We have found that the Three Levels Performance Improvement Process is an effective way for any staff person to diagnose a situation before recommending action. At the least, it enables the analyst to tailor his or her solution to the organization unit’s unique situation. At the most, it may indicate that a solution involving his or her elixir does not address the highest-priority need.

A Situation Requiring Diagnosis

The vice president of operations for the partially fictionalized Property Casualty, Inc. (PCI) has requested that Larry Monahan, one of his procedures analysts, develop an updated, clearer, and more comprehensive claims manual for the organization’s claims representatives.

Larry will be using the fourteen-step Three Levels approach, which appears in Figure 8.1. As we discuss the application of each step to this situation, we will display some of the forms he may use. However, the process should not be forms driven and need not be as formal as it’s depicted here. The heart of the process is the sequence of steps, the questions that need to be answered at each step, the organization of the information obtained in response to the questions, and the link between actions and diagnosis.

FIGURE 8.1. THE THREE LEVELS PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT PROCESS

NOTE: THE PERFORMANCE IMPROVEMENT PROCESS CAN BE USED TO:

• Enhance performance that is at or above standard

• Correct performance that is below standard

Project Definition and Plan

Step 1: Project Defined. In this step, Larry interviews the vice president of operations. His goal is specifically to define the Critical Business Issue (CBI) that stimulated Larry’s assignment. Updating the claims manual is clearly the vice president’s preferred solution to some problem. If Larry is to be an effective diagnostician, he will need to understand that problem. During the interview, he learns that the vice president’s concern is excessive claim payouts. The average amount that PCI is paying per claim is too high and is negatively affecting the company’s margins.

During Project Definition, Larry will also take these actions:

- Learn the specific financial effect the problem is having on the organization.

- Establish project goals based on the desired payout amount.

- Define the scope of the project.

- Identify his client and define the roles he and other key persons will play in the analysis.

- Reach some conclusions regarding the constraints, odds of success, and value of the project.

Assuming that the project makes sense, and that the Three Levels approach is acceptable to his client, Larry proceeds to Step 2.

Step 2: Project Plan Developed. In this step, Larry plans the events and dates for the project. He is careful to indicate the data and data sources he needs at each of the three levels of analysis.

Organization Improvement

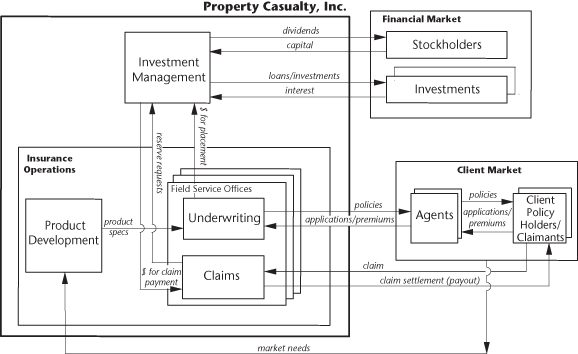

Step 3: Organization System Defined. To be sure that the vice president’s proposed “fix” will solve the problem, and to identify other factors that may affect claim payouts, Larry begins his analysis at the Organization Level. His first step is to develop a Relationship Map of PCI. He knows that this map of functions, inputs, and outputs will help him see how his project fits into the big picture and ensure that he has identified all of the areas he should probe during his analysis. Figure 8.2 is Larry’s map.

FIGURE 8.2. PCI RELATIONSHIP MAP

Step 4: Organization Performance Improvement Opportunities Identified. In Step 4, Larry wants specifically to identify high-impact gaps at the Organization Level. He begins with the focus provided to him by the vice president but is alert to other opportunities. During his analysis, he unearths claims-processing cost as a second high-impact opportunity.

Step 5: Organization Improvement Actions Specified. While he is gathering his data, Larry identifies some of the Organization Level causes of the high-impact gaps. Since he realizes that these causes can be addressed at the Organization Level, without exhaustive analysis at the Process and Job/Performer Levels, he develops a set of recommended actions to address these causes on the basis of the Three Performance Needs at the Organization Level: Organization Goals, Design, and Management. For example, Larry sees no problem with Organization Goals and Design, but in the area of Organization Management, he learns that the underwriting and claims departments often don’t understand the insurance products that come out of Product Development. He recommends vehicles for providing this feedback to product development and for establishing a stronger link between the customer and product development. These Organization Level recommendations will be added to those Larry develops at the Process and Job/Performer Levels.

Step 6: Processes with Performance Payoff Identified. To bridge to the Process Level, Larry analyzes the three PCI processes that have impacts on payout amount. He investigates the underwriting and new-product development processes. While he has no doubt that those processes could be improved, Larry identifies the claim-handling process as the one with the greatest impact on the goals of his project. At this point, Larry updates his plan, specifying the steps he will take at the Process Level. Table 8.1 presents a summary of Larry’s work in Steps 4, 5, and 6.

TABLE 8.1. PCI ORGANIZATION ANALYSIS AND IMPROVEMENT WORKSHEET

Process Improvement

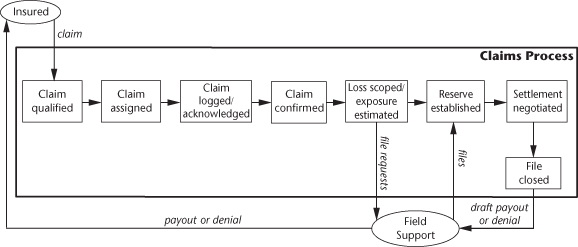

Step 7: Processes Defined. In this step, Larry works with a group of claims representatives and claims supervisors to construct a Process Map, which depicts the claim-handling process as it should flow. (In most instances, this type of group first needs to document the “IS” process as a backdrop for the creation of the “SHOULD.”) Their Process Map appears in Figure 8.3.

FIGURE 8.3. PCI CLAIM-HANDLING PROCESS

Step 8: Process Performance Improvement Opportunities Identified. Having documented the claim-handling process, Larry identifies the desired performance for each process step, the actual performance, any gaps between desired and actual performance, and the impact of those gaps. He identifies significant gaps in the “claim qualified” and “claim assigned” process steps.

Step 9: Process Improvement Actions Specified. In Step 9, Larry identifies the causes of gaps revealed in Step 8 and the Process Improvement actions that will remove the gaps. He limits his list of recommended actions to those that can be taken at the Process Level, without analysis at the Job/Performer Level. Larry finds causes that require clarifying performance expectations and providing feedback.

Step 10: Job(s) with Performance Payoff Identified. As the last step in Process Improvement and as a bridge to Job Improvement, Larry identifies the jobs that contribute to the process steps in which there are gaps. His analysis indicates that the claims supervisor job—not the claims representative job—requires the most attention during the Job Improvement phase. Table 8.2 summarizes Larry’s work in Steps 8, 9, and 10.

TABLE 8.2. PCI PROCESS ANALYSIS AND IMPROVEMENT WORKSHEET

Job Improvement

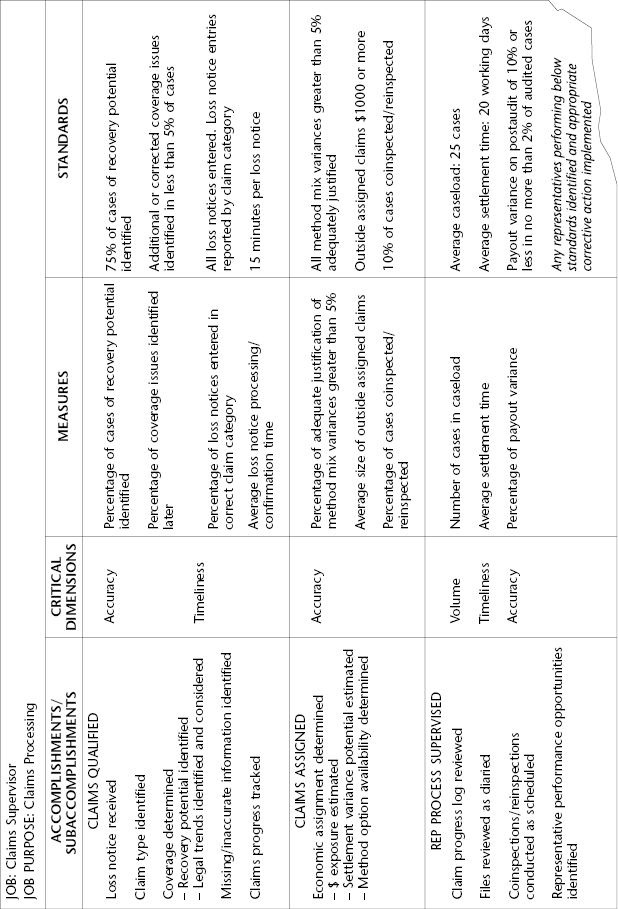

Step 11: Job Specification Defined. In Step 11, Larry and a group of claims supervisors and managers define the outputs and standards that the “SHOULD” process requires of the claims supervisor job. Table 8.3 displays a portion of the Job Model that the group creates for the claims supervisor.

TABLE 8.3. PCI CLAIMS SUPERVISOR JOB MODEL

Step 12: Job Performance Improvement Opportunities Identified. The Job Model produced in Step 11 describes the performance that the claims supervisor needs to produce. In Step 12, Larry compares the current performance to the Job Model’s standards and identifies gaps, the impact of the gaps, and the causes of the gaps. He uses the Human Performance System (see Chapter Five) to help him identify the causes of gaps. One of his more significant findings is that the claims supervisors, when qualifying claims, should identify the recovery potential 75 percent of the time. They are doing this in only 18 percent of the cases. Larry’s analysis reveals that supervisors are not measured, evaluated, or trained in recovery-potential identification. Table 8.4 summarizes some of his analysis for the supervisor job.

TABLE 8.4. PCI JOB ANALYSIS WORKSHEET

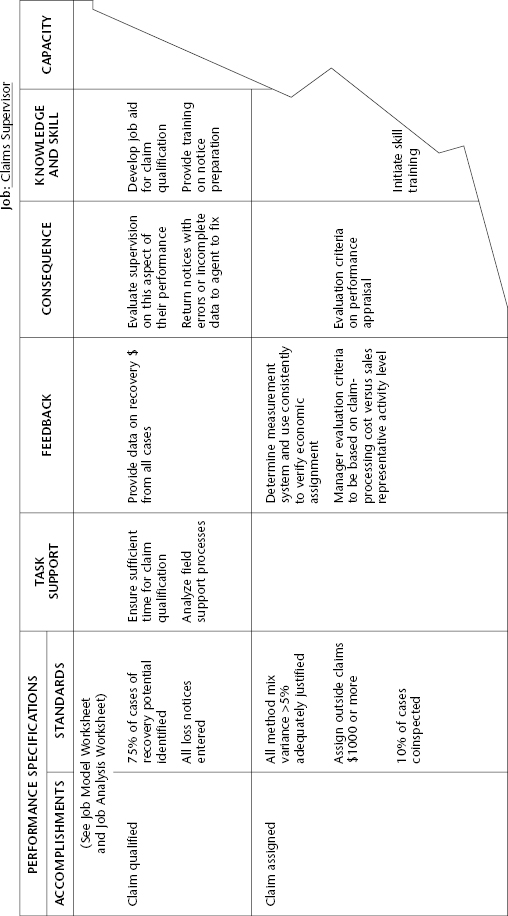

Step 13: Job Improvement Actions Specified. For each gap, Larry develops a recommended gap-closing action. Cognizant of the fact that an effective medicine is one that fits the disease, his action development is focused on the causes of the gaps. A partial picture of Larry’s Step 13 is in Table 8.5.

TABLE 8.5. PCI PERFORMANCE SYSTEM DESIGN WORKSHEET

Implementation

Step 14: Performance Improvement Actions Implemented and Evaluated. In this final step in the process, Larry summarizes the recommendations from all three levels of his analysis. He uses the questions associated with the Nine Performance Variables (Chapter Two, Table 2.2) as a checklist to make sure his recommendations address the performance needs at all three levels. He conducts a cost-benefit analysis on the recommendations and develops a proposed high-level implementation plan. Last, he takes his recommendation package through the process that he and the vice president of operations agreed on during the project definition and planning phase.

Summary

At first blush, this process may appear to overkill the assignment. After all, Larry was just asked to update a manual. However, he took it upon himself to get at the problem that had stimulated the request. Through the Three Levels Performance Improvement Process, he identified actions that will result in a far more significant payback than what would have been realized from a better claims manual.

This entire process could certainly occupy twenty days of Larry’s time. However, we have to examine the output of that twenty-day analysis and compare it to the output of twenty days of manual rewriting. We also need to acknowledge that Larry could have used shortcuts that retained the integrity of the Three Levels approach and significantly reduced the number of work hours and amount of elapsed time.

Larry is an effective “performance doctor.” He specifically pinpointed the illness. He thoroughly diagnosed the patient at the Organization, Process, and Job/Performer Levels, and he recommended a treatment that was based on his diagnosis. He has provided an exemplary staff service: the analysis and improvement of line performance.