CHAPTER THIRTEEN

MANAGING PROCESSES AND ORGANIZATIONS AS SYSTEMS

Labor can do nothing without capital, capital nothing without labor, and neither labor nor capital can do anything without the guiding genius of management.

—W. L. MACKENZIE KING

You shouldn’t expect most of your managers to exhibit “guiding genius.” However, you should expect guiding competence. A competent manager understands the way his or her organization functions and is able to manage the variables that can make it better. Chapter One is devoted to our worldview, which includes the belief that organizations (at all levels) function as adaptive systems. Because your organization operates as a system, you will be most effective if you manage it as a system.

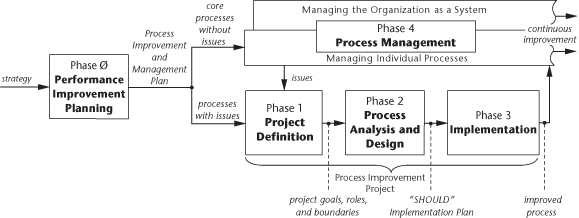

Now that we have presented a methodology for and the pitfalls in Process Improvement (Chapters Nine, Ten, and Eleven) and have covered the measurement system (Chapter Twelve) that needs to underlie continuous Process Management, we can address Phase 4 of the framework, shown in Figure 13.1.

FIGURE 13.1. THE RUMMLER-BRACHE PROCESS IMPROVEMENT AND MANAGEMENT METHODOLOGY

Process Management

The first part of Phase 4 is ensuring that an individual core process, in most cases one that has been through Phases 1 to 3, is continuously improved.

While most of Phase 2—Process Analysis and Design—is carried out by nonexecutive personnel, Phase 4 is the responsibility of the people who run the business. To effectively carry out this role, executives need:

- To understand the what, why, and how of both Process Improvement and Process Management

- To develop a Process Improvement and Management plan, which is the primary output of Phase Ø

- To provide the communication, measures, resources, skills, rewards, and feedback (the Human Performance System components) necessary to reinforce Process Management

- To establish the infrastructure and take the actions described below

Selecting Core Processes. While a long-range goal may be to establish a Process Management plan for every process, most organizations begin by identifying the critical few processes that warrant the investment in ongoing Process Management. These processes are those that have the greatest impact on the strategic success of the organization.

Therefore, the seeds of Process Management are sown in Phase Ø, in which “core processes” are identified. During Phase Ø, executives agree upon a specific, up-to-date strategy. They then use Critical Success Factors to identify the core processes from their inventory of primary, support, and management processes.

As you can see in Figure 13.1, some core processes, because they need either substantial or incremental improvement, go through Phases 1 to 3 before entering Phase 4. While the other core processes could be improved, they are not priorities for Process Improvement Projects; they go directly to Phase 4.

A core process is one that influences either a competitive advantage that must be overcome or a competitive advantage that senior management wants to establish, reinforce, or expand. For example, if order-cycle time is a potential competitive advantage, order processing is a strategic process. If the quality of customer service is a competitive advantage, the customer service process is core. If new products are central to the competitive advantage, product development and product introduction are core processes.

These examples of core processes are all primary processes (those that produce a product or service visible to the customer; see Chapter Four). Support and management (purely internal) processes can also be strategic. For example, if the cost of producing a product or service is a competitive advantage, the budgeting and capital expenditure processes may be as strategic as design, material management, and manufacturing. If the ability to quickly respond to the needs of a rapidly changing market is a competitive advantage, market research and planning are probably core processes. Similarly, training, forecasting, and safety management could be core processes.

Process Measures. If we had to select the single action that would make the greatest contribution to lasting Process Management, it would be the development and installation of a process-based measurement system that is linked to Organization Level and Job/Performer Level measures. Chapter Twelve is devoted to this subject.

Process Owners. To ensure that someone with clout is looking at and taking action to improve the performance of an entire cross-functional process, many organizations are appointing an individual as the Process Owner of each core process. A Process Owner plays some or all of these roles:

- Monitors process performance and reports periodically to senior management about how well the process is meeting customer requirements and internal goals, as well as about any indications that the process is being suboptimized.

- Chairs a cross-functional Process Management Team, which is responsible for the performance of the process. It sets the goals, establishes the process plan and budget, monitors process performance against the goals, and takes action in response to opportunities for Process Improvement.

- Serves as a “white-space ombudsman,” who facilitates the resolution of interface problems among the functions that contribute to a process.

- Serves as the conscience and champion of the process.

- Evaluates and, in highly structured organizations, certifies the process.

Without a Process Owner, the “white spaces” tend to be ignored. As each line manager manages his or her piece of the process, functional optimization or process suboptimization (described in Chapter One) is likely to occur.

Like a matrix manager, who oversees the cross-functional performance of a product or a project, the Process Owner oversees the cross-functional performance of a process. Unlike a product or project manager, however, the Process Owner does not represent a second organization structure. Individuals are not continually torn between their commitments to their vertical (line) and horizontal (product or project) managers. In effective Process Management, reporting relationships remain vertical; the functional managers retain their power. The horizontal dimension is added if the functional managers are judged by their departments’ contributions to one or more processes and if Process Owners ensure that interface problems are resolved and that process considerations dominate functional interests. There is one more distinction between a Process Owner and a product or project manager: products and projects come and go; processes are permanent.

Given this pivotal role, the selection of the Process Owner is critical. While not all of these characteristics are essential, a Process Owner tends to be someone who:

- Holds a senior management position

- Holds a position that gives him or her major equity in the total process (the most to gain if the process succeeds, and the most to lose if it fails)

- Manages the largest number of people working in the process

- Understands the workings of the entire process

- Has an overall perspective on the effect the environment has on the process and the effect the process has on the business

- Has the personal ability to influence decisions and people outside his or her line-management responsibility

The Process Owner’s responsibility is usually associated with the position, rather than with an individual. For example, we worked with a telephone company in which the vice president of finance was appointed Process Owner for the billing process. When he left that position, his successor became the Process Owner.

We were initially surprised by the low level of conflict between effective Process Owners and the managers of the functions that contribute to the processes. We believe that good Process Owners do not threaten line managers, because they are doing things that nobody has done before. They are adding value without taking anything away from other managers.

Institutionalizing Process Management

In an organization that goes beyond Process Improvement Projects and institutionalizes Process Management, each key process has:

- A map that documents steps and the functions that perform them.

- A set of customer-driven measures, which are linked to Organization Level measures and drive functional measures (see Chapters Four and Twelve). In an institutionalized Process Management environment, functions cannot look good against their measures by hurting other functions and the process as a whole.

- A Process Owner.

- A permanent Process Team, which meets regularly to identify and implement Process Improvements.

- An annual business plan, which includes, for each core process, expected results, objectives, budget, and nonfinancial resource requirements.

- Mechanisms (such as process control charts) for the ongoing monitoring of process performance.

- Procedures (such as root-cause analysis) and vehicles (such as Process Teams) for solving process problems and capitalizing on process opportunities.

To ensure that processes meet these and other performance criteria, some organizations, including Ford and Boeing, have established process certification ratings. To achieve the top rating on a four-point scale, a Ford process must meet thirty-five criteria. These criteria range from the need for the process to have a name and be documented to a requirement that the process be assessed by customers as free of defects. The Process Owner takes primary responsibility for administering the evaluation and certification process.

Institutionalized Process Management is not just a set of certified processes. It is also a culture in which:

- Process Owners, Process Teams, and line managers practice continuous process improvement, rather than sporadic problem solving.

- Managers use their Relationship and Process Maps as tools for planning and implementing change, orienting new employees, evaluating strategic alternatives, and improving service to their internal and external customers.

- The needs of internal and external customers drive goal setting and decision making.

- Managers routinely ask and receive answers to questions about the effectiveness and efficiency of processes within their departments and about cross-functional processes to which their departments contribute. The answers to these questions require a process-based measurement system.

- Resources are allocated based on process requirements.

- Department managers serve as the Process Owners for their intrafunctional processes.

- Cross-functional teamwork is established through the enhanced understanding of other departments, the streamlining of interfaces, and the compatibility of goals.

- Optimum process performance is reinforced by the Human Performance Systems in which people work (see Chapter Five).

When Process Management is institutionalized in an organization, the systems view (see Chapter One) is the framework for addressing performance problems and opportunities. Process effectiveness and efficiency are the end to which policy, technology, and personnel decisions are means.

Managing the Vertical and Horizontal Organizations

Institutionalization of Process Management requires the peaceful coexistence of the vertical and horizontal dimensions of an organization. In most cases, organizing around processes is not practical. While a process organization structure (discussed further in Chapter Fourteen) eliminates the tension between the vertical and horizontal, it merely creates a different kind of white space … between processes. Furthermore, it may require additional people, obstruct sharing of learning and resources, and erect career path barriers. In most process-based organizations, functions remain as “centers of excellence.”

How does an organization establish effective vertical and horizontal structures? In our experience, the key is measurement. As we suggest in Chapter Twelve, establishing customer-focused, process-driven measures is the first step. In a process-driven environment, each functional manager is still responsible for achieving results, allocating resources, and developing policies and procedures. The only difference from a traditional (purely vertical) organization is that each function is measured against goals that reflect its contribution to processes. Line managers have as much authority as in any traditional organization. There is no tug-of-war between two bosses, as in many matrix-managed organizations.

A department always contributes to the greater good. In an institutionalized Process Management environment, that greater good is the processes that serve the organization strategy. Because Process Management fosters symbiotic “we’re all in this together” relationships between suppliers and customers, functional managers may need assistance in managing the “white space.” That assistance is available from the Process Owner.

In summary, Process Management can coexist quite peacefully with the functional organization because:

- It doesn’t change the direction of the business.

- It doesn’t (necessarily) change the organization structure or reporting relationships.

- It ensures that functional goals are aligned with process goals.

- It doesn’t change accountability or power.

- It changes how the business is conducted only because it ensures that processes (which are there already) are rational.

The Role of Top Management

An organization does not have to implement Process Management all at once. A top manager who is interested in Process Management should begin by instituting a couple of Process Improvement Projects. If these projects successfully address Critical Business Issues, he or she should consider institutionalizing Process Management, at least for the organization’s core processes. A top manager’s role in institutionalization may include:

- Identifying core processes

- Appointing or serving as a Process Owner

- Appointing permanent Process Teams

- Asking and requiring answers to the questions behind the Nine Performance Variables

- Using process measures as the foundation for performance evaluation, rewards, and troubleshooting

- Chairing a Process Owner panel that conducts process reviews, which are similar to traditional operations reviews

- Installing and managing a process planning system, which resembles typical business planning

- Ensuring that the work environment (rewards, feedback, resources) supports process effectiveness and efficiency

Process Improvement and Management and the Three Levels of Performance

Effective Process Improvement is not limited to the Process Level of Performance. Process Improvement Projects with the greatest impact begin with the identification of a Critical Business Issue associated with a key process. Issue and process identification should be based on strategic goals at the Organization Level. Process Improvement cannot take root if it is limited to the Process Level. All system enhancements have to be reflected in the jobs and the environment at the Job/Performer Level.

Similarly, ongoing Process Management is not just management of the Process Level. An ongoing assessment of Organization Level needs should direct the Process Management priorities. In addition, a cornerstone of Process Management is the monitoring and improvement of the Job/Performer Level. To manage the performance of a process, one must manage the performance of the people who work within that process. To manage people’s contributions to process effectiveness, one must manage the variables of the Human Performance System—Performance Specifications, Task Support, Consequences, Feedback, Skills and Knowledge, and Individual Capacity.

Managing an Organization as a System

Everything we’ve covered up to this point addresses the first part of Phase 4, which relates to actions we might take to manage and continuously improve a single process. At some point, all of the individual Process Management efforts have to be integrated with each other and with the goals at the Organization Level. We call this integration “managing organizations as systems.”

Before you begin managing your organization as a system, you should build a logical system to manage. We will illustrate the process with Computec, Inc., the organization we have used frequently as an example. Computec’s top managers were concerned about the plateauing of the company’s revenues and its loss of market share. They began to address the situation by building an intelligent system.

Evaluating the System

The changes have been successfully implemented. Computec has built a system that works. Now the top team’s challenge is to manage the system it has built. However, before the system can be effectively managed, it is necessary to develop a mechanism for measuring and evaluating key components of the system. Toward this end, Computec developed the following:

- A report card for evaluating the performance of each of the four strategic processes. Areas for evaluation include customer feedback, internal requirements (such as performance against budget), ability to respond to change, and extent of continuous improvement. The data for the evaluation come directly from the performance measurement system, which documents actual performance and compares it to the Process Goals (see Step 9).

Figure 13.2 illustrates how process performance information comes together to form the basis of top management’s “instrument panel.” The dials on the instrument panels of the managers at the next level may consist primarily of subprocess and department measures. At the next level (which may or may not be managerial), the instrument panel may contain measures of individual process steps and jobs. This approach ensures that each level has an instrument panel and that the dials on each of these panels link to those above and below. - A report card for evaluating each Process Owner in terms of his or her contribution to the effectiveness of the process. The items on this report card are based on top management’s clear delineation of the responsibilities of the Process Owner (see the sample list earlier in this chapter). For example, Computec Process Owners are evaluated on how well they keep the rest of the top team informed of process performance and how well they help resolve any “white-space” conflicts between functions.

- A report card for evaluating the vice president of each function on how well that function supports the processes to which it contributes. For example, the vice president of marketing is evaluated on how well marketing supports product development and introduction. The evaluation is based on the process steps carried out by that function and on the functional goals (in such areas as customer requirements and budget) that evolved from the Process Goals. The Computec Function Models (see Chapter Twelve) were particularly useful in the development of these rating categories.

FIGURE 13.2. MANAGING THE ORGANIZATION AS A SYSTEM

Vice presidents are evaluated not only on how well their functions achieve their goals but also in “softer” areas, such as degree of cooperation with other functions for the good of the process, responsiveness to changes required for process success, and the degree to which Human Performance Systems support individuals and teams who contribute to process success. The performance appraisals of the four Process Owners assess them both as Process Owners and as leaders of functions that exist to support processes.

The Systems Management Processes

At this point, Computec has created a system that makes sense, and the company has developed mechanisms for evaluating the key aspects of that system: the processes, the Process Owners, and the function managers. Now let’s examine the ways in which some of the basic management processes help the senior management team manage Computec as a system.

In the annual planning process, the Computec president, Process Owners, and vice presidents:

- Update the strategy and operating plan.

- Identify new Organization Level outputs and Organization Goals.

- Confirm the identity of the strategic processes and update Process Goals to ensure that they reflect Organization Goals.

- Identify the process changes required to meet the new Process Goals. These changes may include modifications to the processes themselves, new goals for process segments, or resource shifts.

In the annual budgeting process, the same players:

- Negotiate budgets for the processes, which are based on the Process Goals that were established as part of the planning process. (The Process Owners’ commitment to budget allocation is particularly critical.)

- Negotiate function budgets, which are based on the process budgets and on each function’s contributions to the Process Goals.

- Roll up the process and function budgets and marry them with the organizationwide budget, which was established in the strategy.

In the monthly operations-review process, the top managers:

- Examine product and market performance in terms of customer satisfaction goals.

- Examine product and market performance in terms of revenue and profit goals.

- Examine cost performance in terms of budget goals.

- Examine process performance in terms of the Process Goals established for customer satisfaction, revenue and profit, and cost. Each function’s performance is reviewed in terms of the degree to which it is providing the agreed-upon process support. At this step in the review, the team is ready to ask a number of questions:

- Why is performance better (or worse) than we expected? Is this a blip or a trend? Is this a surprise? If so, why? Is the process flawed? Did functional priorities supersede process priorities? Is our goal setting, planning, or budgeting deficient?

- Do we need to add to or modify our goals?

- Do we need to reallocate resources? If so, which process or function gets more? How much more, and from where?

During the operations-review meeting, the president asks the questions. The Process Owners provide most of the answers and are supported by the function heads. The answers lead to decisions, which in turn result in action items that are assigned to individuals. These action items are documented and categorized as changes in policy, changes in goals, changes in resources, changes in processes, changes in reporting relationships, and changes in management practices.

In the biannual performance review process, the president provides grades for the processes, Process Owners, and function managers. These ratings serve as the basis for the annual allocation of bonus money. The size of the bonus pot is determined by the profitability of the company. We believe that this scenario has some key distinctions from traditional management:

- Because the measures are customer focused, the customer’s voice is heard throughout the performance review process.

- Because the goals are process driven, the top team is able to review the performance of the business comprehensively.

- Because the goals are process driven, the top team can review both the results and the ways in which those results are achieved. Since the team understands the reasons for the results, it has greater control over the business.

- Because the Process Owner plays a key role in the management process, the voices of “the way work gets done” and of “white-space management” are never drowned out by other considerations.

- Because functional goals are subordinate to process goals, no departmental head can command an inappropriate share of the resources.

- Because the Three Levels are incorporated into the Performance Management process, change is more intelligently managed. The top team is less likely to make strategy or policy decisions without developing an implementation plan that includes actions at the Process and Job/Performer Levels; to initiate systems improvements without determining their impact on the Organization and Job/Performer Levels; or to take action to improve employees’ performance, other than in response to the needs of the Organization and Process Levels.

The Systems Management Culture

We have found that the culture of an organization in which systems are being managed differs from the culture of a typical organization. Table 13.1 contrasts the traditional (vertical) and systems (horizontal) cultures. Within a systems culture, we find that managers at all levels are able to answer yes to the systems management questions contained in Table 13.2.

TABLE 13.1. COMPARISON OF THE TRADITIONAL (VERTICAL) AND SYSTEMS (HORIZONTAL) CULTURES

| Traditional Culture | Systems Culture |

|

|

TABLE 13.2. SYSTEMS MANAGEMENT QUESTIONS

|

Summary

Managing organizations as systems involves understanding and managing the Nine Performance Variables that serve as the theme of this book. The business system is made up of inputs, outputs, and feedback at the Organization, Process, and Job/Performer Levels. At each of the Three Levels, the system requires clear and appropriate goals, logical design, and supportive management practices.

Performance measures provide the latticework of the system. A Three Levels measurement system provides a window on more than just results. By monitoring and improving those factors that influence results, managers are able to cause more systemic improvement and to understand what’s needed to implement change.

Managers become heroes in the systems management culture by understanding their business, collaborating with other departments to get a job done, subordinating the optimization of their departments to the common good of the process, and creating Human Performance Systems that equip people to make their maximum contributions to the system and that reinforce them when they do.