CHAPTER FIFTEEN

CREATING A PERFORMANCE-BASED HUMAN RESOURCE DEVELOPMENT FUNCTION

Genius will live and thrive without training.

—MARGARET FULLER

In most organizations, training is a sizable investment, more sizable than senior managers realize. They know the amount of the human resource development department’s budget. However, the total investment in training, which includes salaries of participants, is less visible and would be a surprise to most executives. Of more significance is the fact that even fewer of them know the return they are getting on that investment. Can you envision a manager who could not cite the return on his investment in a $50,000 telecommunications system? Can you envision a manager who could tell you the return he is getting on a $50,000 investment in communications training for managers?

Training is often seen as an employee benefit (like company picnics or contributions to the insurance plan), which is not expected to provide a tangible return. Isn’t training just part of enlightened management, intrinsically good and unquestionably valuable in immeasurable ways?

No. Training should be treated like other investments:

- If the return on a given training investment is not easily quantified, how can a manager describe the specific benefits to the organization of that training effort?

- How is the investment in training to be assessed (and compared to other potential investments) before the investment is made?

- If top managers are committed to spending a certain percentage of revenue on training, how can they be sure that they are investing in the right training?

The answer to all three of these questions is the same. With the exception of situations in which an employee is being developed for a new job, the purpose of training is to improve current performance. Therefore, training should be assessed in terms of its impact on performance.

Two Views of Performance Improvement

There are two views of performance. In the prevailing view, people exist in a vacuum. If managers want to establish or improve a certain performance output, all they need to do is arrange for the proper training input. Figure 15.1 shows this limited perspective. When people in the human resource development department hold this view, their response to a request for training tends to be “You got it. When do you want it? Do you have enough money for a multimedia program?”

FIGURE 15.1. THE “VACUUM” VIEW OF PERFORMANCE

Unfortunately, the world of performance is not simply “skills and knowledge in, performance out.” This reality leads to the second view of performance: the systems view. In the systems view, represented by the Nine Variables that serve as the theme of this book, human performance is a function of:

- The Job/Performer Level, where job outputs are defined and the Human Performance System establishes the environment in which people work

- The Process Level, where work flows are defined

- The Organization Level, where the strategy provides the direction, and the organization configuration provides the structure in which people work

Every trainee (or potential trainee) is a performer who functions within all Three Levels of Performance and is influenced by each of the Nine Performance Variables. As Table 15.1 shows, Skills and Knowledge (which is all training can provide) is one small part of one of the Nine Performance Variables. Without the perspective of the Three Levels, training is likely to be prescribed when training is not needed. When not supported by the Human Performance System, by work processes, and strategy and structure, training that is needed is nevertheless sure to fail.

TABLE 15.1. TRAINING’S ROLE IN THE NINE PERFORMANCE VARIABLES

The systems (Three Levels) view has significant implications for the human resource development (HRD) function, particularly because training is one of management’s favorite performance improvement solutions.

HRD is often asked to bring about major organizational change with the small lever shown in Table 15.1. A review of the Nine Variables framework shows that job performance is a function of Job Goals, Job Design, and Job Management, where Skills and Knowledge is but one of six factors. In our thirty years of experience, we have seldom seen a job performance “problem” that could be significantly improved by manipulating the Skills and Knowledge (Training) factor alone. Senior management should either provide HRD with a longer lever or realize that HRD’s influence on organization performance is important but very limited.

The Three Levels context and tools have implications for all areas of HRD. We will devote the rest of this chapter to exploring four of these areas:

- Determining training and development needs

- Designing training

- Evaluating training

- Designing and managing the HRD function

Determining Training and Development Needs

Our basic assumption is that HRD is in the performance improvement business. The question that should be asked in planning and implementing all HRD interventions is how this activity affects the performance of the business.

HRD can discover training needs in two ways: reactively (in response to requests for training) and proactively (as a result of planning to meet organization needs through training). The Three Levels approach can help identify training needs in both situations.

Reacting to Requests for Training. When responding to a request for training, the HRD professional must realize that the requester probably has not conducted a thorough analysis and most likely does not know the limitations of training as a performance improvement intervention. All he or she knows is that there is a feeling of pain. The HRD needs analyst’s primary objective has to be to understand the performance context of the request. Only through that understanding can he or she determine whether any training is needed and, if so, the specific objectives that the training should meet.

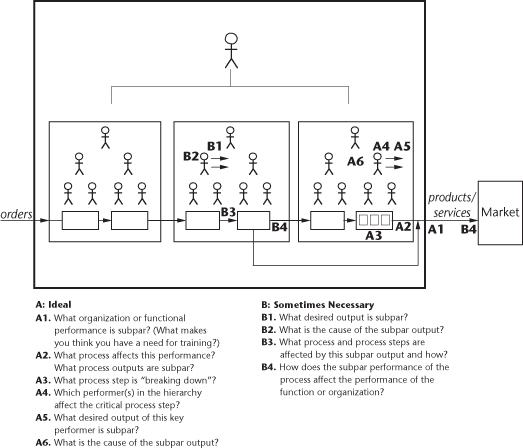

As Section A of Figure 15.2 shows, the ideal response to a request for training follows an “outside-in” process. It begins at the Organization Level and moves through the Process Level to the Job Level. Sometimes political factors prevent the HRD analyst from beginning at the Organization Level. Under these circumstances, we recommend the less ideal (but still performance-based) “inside-out” process displayed in Section B.

FIGURE 15.2. TWO APPROACHES TO TRAINING-NEEDS ANALYSIS

The ideal needs-analysis process is more likely to get at the real issues behind the training request and is more likely to unearth performance needs that cannot be met by training. However, it may be more risky because it goes beyond what is normally expected of the HRD function. It also tends to be more time-consuming. The “sometimes necessary” approach, while less countercultural and time-intensive, may not address the most significant organization need. While the analyst does verify the need for training before proceeding with any development, he or she is locked into the assumption that the person identified by the requester represents the greatest performance improvement opportunity.

To illustrate the ideal process, let us examine a request for training. Sharon Pfeiffer, the vice president for operations at Property Casualty, Inc. (PCI), the partially fictionalized company introduced in Chapter Eight, has asked Stephen Willaby, the director of HRD, for a comprehensive training program for incumbent claim representatives. She tells him that claim reps’ training is a high priority for her this fiscal year and that she will provide the funding from the operations budget.

If Stephen sees the vice president’s request as a trigger to conduct a training-needs analysis, he will most likely use one of these three techniques:

- A training-needs survey, in which reps and their managers are asked to identify the skills and knowledge required to perform the claim rep job

- A competency study, in which a group of claim reps and claim managers are asked to identify the general competencies of an effective claim rep (analysis, computation, and written and oral communication)

- A task analysis, in which effective claim reps provide a list of the tasks they perform while doing their job

Any of these three approaches is better than developing a program without a needs analysis. They gather some real-world information, they can be done quickly and inexpensively, and they are not risky for Stephen. However, these methodologies share a significant weakness: none of them is tied directly to the organization, process, and job outputs that are the reason the claim representative job exists. Knowledge and skills, competencies, and tasks are all inputs to the results that PCI expects the reps to produce.

The failure of these three techniques to focus on performance outputs would be misguided if Stephen were being asked to develop entry-level training for claim reps. In this situation, however, his input focus is worse than misguided. At best, it is wasteful; at worst, it is dangerous. Because the vice president has requested the course for incumbent reps, we can assume that she wants to improve current performance. The course or curriculum that results from any of these three needs-analysis techniques may address the true performance needs that spawned the request; but is this training buried in a sea of material that covers parts of the claim rep job that are being performed satisfactorily? Is training of any kind for claim reps the solution to Sharon’s concern? Is the claim rep job the one that should be addressed? What’s the real performance need? If Stephen were to take the ideal approach outlined in Section A of Figure 15.2, he would:

Stephen would develop training only for the Skills and Knowledge needs. Ideally, he would have the charter to recommend changes in nontraining (environmental) areas as well.

During this six-step process (a distillation of the fourteen-step performance improvement process described in Chapter Eight), Stephen would most likely visit the claims office that is performing best (in terms of measures related to the Critical Business Issue) and two or three other offices. In each office, the required information could be gathered by interviewing the office manager and by interviewing and observing effective and ineffective claim supervisors and reps.

The PCI request was actually made by an insurance company executive. Fortunately, the real Stephen arranged for a Three Levels analysis. As it turned out, the job that was having the most impact on the Critical Business Issue (excessive claim payouts) was claim supervisor. Thus, not only did claim reps not need training, they were not even the performers with the greatest opportunity for improvement. Claim supervisors needed improvement in two of their job outputs: qualifying claims and assigning claims to claim reps. Training was part of the solution, but the primary need was for a system of measurement and feedback. If the director of HRD had responded unquestioningly to the request of the vice president for operations, he would have developed an impressive training program for claim reps—an impressive waste of PCI’s money.

Proactively Planning for Human Resource Development. HRD professionals certainly should not try to do away with training requests. However, they should not be driven by training requests. The way out of the purely reactive mode is to initiate HRD plans. The steps in an HRD planning process are:

If an unplanned training request comes into the HRD function, an HRD representative and the client contact should discuss whether it represents an addition to or a replacement for something in the plan. If it is an addition, required resources can be negotiated with the client.

Even if HRD is limited to training interventions, this simple planning process results in clear priorities, which are based on the customer’s long-term needs. It places the needs in the overall performance context of the business, and it enables the HRD department to make its resource decisions on a firmer business footing.

Designing Training

The “vacuum” view of performance leads to subject-matter-driven training and development. Training programs tend to address the hot topic of the day, or perceptions of what “they” need.

Here is a typical example of a subject-matter-driven training design. An HRD department was asked to train a large group of new people, whose job was to interview applicants for unemployment compensation. The design assignment was given to Matthew, a training specialist. He began by identifying subject matter areas relevant to the new interviewer. He examined existing bodies of knowledge concerning interviewing techniques and psychology. Matthew identified interviewing technique subject matter areas, such as developing the types of questions to ask, using questioning and probing skills, and interpreting answers. While exploring interviewing psychology, he uncovered subject matter areas that focused on an interviewee’s behavior and personality makeup. After a considerable amount of apparently relevant subject-matter research, Matthew developed a three-day course that made extensive use of videotape and role-play exercises.

The Three Levels view, by contrast, leads to performance-driven training and development based on the needs-analysis approach already described. Performance-driven training design (which fits well with the techniques described by others as Criterion-Referenced Instruction or Learner-Controlled Instruction) suggests the approach used in the following example. Gwen, the educational technologist who was given the new-hire interviewing/training assignment, began by determining what the new interviewer was expected to do on the job. Specifically, she identified all the decisions the interviewer was expected to make, particularly the final decision (output) of the typical interview. From this analysis, Gwen learned that in all cases the interviewer’s output was to decide where to refer the interviewees. There were four possibilities: Office A, where the applicants would receive unemployment compensation; Office B, where the applicants would be referred to jobs (because they were able to work and didn’t qualify for compensation); Office C, where the applicants were interviewed by a psychiatrist (because they had psychological problems that would interfere with job placement); and Office D, where they were interviewed by the chief interviewer (because the applicants presented special problems or didn’t clearly belong in one of the other three offices). On the basis of this information, Gwen concluded that the task of the new interviewers was primarily one of categorizing, or sorting. They were expected to decide which of the four offices to send applicants to. Thus, she decided that the subject matter of the training should consist of the following steps, presented in this sequence:

The resulting one-day course did not require elaborate instructional design or expensive media. It concentrated on teaching the interviewers to discriminate among the offices to which various applicants could be sent.

Without going through an exhaustive or overly formal analysis, Gwen addressed all Three Levels: she determined what the organization needed from the interviewer, she examined the interview process, and, on the basis of this information, she identified the skills and knowledge needed by the performers. Unlike Matthew, who based his course on an academic and generic model of interviewing skills, Gwen let the subject matter of the course be driven by the real world of her organization. Gwen’s design was based on performance.

Evaluating Training

Evaluating training in a vacuum is a waste of time. A training program may have well-stated learning outcomes, appropriate media, excellent materials, and effective instruction. However, if the training addresses the wrong performance area, is not reinforced by Consequences and Feedback, is not supported by a well-designed work process, or is not linked to the direction of the organization, it is not worth the investment. With typical methods of evaluation, a workshop could win awards for instructional design the same week that the company files for Chapter 11 protection. Performance impact evaluation, by contrast, does not allow a course to look good without its also having a significant impact on the performance of the business.

Figure 15.3 shows where four types of evaluation fit into our basic systems diagram. All four types of evaluation are valid. The ideal course is liked by trainees, teaches what needs to be taught, provides skills that are used on the job, and provides skills that have a positive impact on the performance of the organization. However, most evaluations are of Types I or II, which are “upstream” from the performance that ultimately matters. Performance impact evaluation focuses on Types III and IV.

FIGURE 15.3. FOUR TYPES OF EVALUATION

One use of performance impact evaluation is to help avoid or eliminate unneeded training. For example, if the director of engineering has requested a workshop in report writing, it would be readily apparent how to evaluate trainees’ satisfaction (a reaction questionnaire) and learning (a test). If, however, the requester would be unable to determine whether the new writing skills were being applied on the job and, more important, whether their application was having any effect on the engineering department’s performance, the training would be a questionable investment.

Another use of performance impact evaluation is to identify areas in which management needs to support the training. For example, a training course on quality control would be fairly simple to assess with Type I and Type II evaluations. As Types III and IV are discussed, the HRD specialist and the client may realize that if management does not take action to support the use of the quality-control techniques (by providing resources and rewards), the best training in the world will have no effect on performance.

If the HRD analyst has determined the training needs, as just described, evaluation (especially Type IV) should not present a problem. Because the training needs directly affect documented organization performance problems or opportunities, the training can be evaluated in terms of its impact on those problems or opportunities. The questions that appear in Column A of Figure 15.2 provide the framework for performance impact evaluation.

Designing and Managing the HRD Function

The Three Levels approach to determining training needs, to designing training, and to evaluating training suggests a different kind of HRD department. As a matter of fact, this type of HRD function can transform itself from a training operation to the organization’s performance department.

A performance department differs from a traditional training function in a number of ways. Its people:

- Understand that their mission is to improve performance, not to provide skills and knowledge.

- Only conduct training and development that are linked to organization performance needs.

- Only conduct training and development that are supported by the environment in which the trainees work (the Human Performance System).

- Evaluate training and development according to their contributions to organization performance needs.

- Conduct diagnoses that go beyond training—and development-needs analysis. They are interested and skilled in unearthing nontraining problems, such as Task Interference, poor Feedback, and unsupportive Consequences.

- Recommend solutions to both training and development and nontraining and development needs.

- Understand the business at all Three Levels of Performance and the influence of all Nine Performance Variables.

- Understand that the department is a business and must be run as a business.

To expand on the last item in the list, the performance department is an organizational subsystem; it is subject to the systems laws described in Chapter One. As a business, it also has a clear strategy (including a specific identification of products or services and customers) that is linked to the organizationwide strategy, and it is structured to run as a performance business whose subfunctions carry out needs analysis, design, development, delivery, and evaluation. Figure 15.4 shows one configuration for a performance department.

You should not infer from Figure 15.4 that a performance department must include a minimum of twenty people; a number of functions can be performed by the same person. As a matter of fact, the department in Figure 15.4 could be staffed by as few as three people.

Moving from the Organization Level to the Process Level, we see that the performance department includes the traditional training processes: course development, course delivery, and course evaluation. However, it also includes processes for organization, process, and job-needs analysis and for nontraining interventions (designing measurement systems, feedback systems, and consequence systems).

At the Job/Performer Level, the performance department structures jobs to include analysis, design, planning, evaluation, and consulting, as well as development and delivery responsibilities. Lastly, the manager of the performance department creates a Human Performance System that supports a holistic performance mission. Since the manager wants the performance department’s staff to identify performance improvement opportunities and design multifaceted solutions, he or she doesn’t measure the staff on “number of classroom days.”

Frankly, we don’t care whether it is the HRD department that assumes the role of performance department, as long as somebody does. We focus on HRD because that tends to be the natural place for this expertise and set of services to reside. However, we have worked with organizations where HRD fulfilled the traditional training role, and comprehensive performance diagnosis and improvement were the mission of a separate department.

Summary

We believe that HRD functions are uniquely positioned to become their organizations’ performance departments (or, at least, performance-based HRD departments). Reflecting the Three Levels–based systems view, rather than the limited and potentially counterproductive “vacuum” view, performance departments realize that training is a very small lever with which to move the world, no matter where the fulcrum is placed. Their people identify needs and evaluate contributions at all Three Levels of Performance. They are as comfortable at the Organization and Process Levels and in nonperformer components of the Human Performance System as they are in the classroom, and they are credible businesspeople who are making a demonstrably significant contribution to the company’s competitive advantage.