Chapter 18. Business Strategy

In strategy, surprise becomes more feasible the closer it occurs to the tactical realm.

| What we’ll cover: |

| Competing definitions of business strategy |

| Strategic fit: a case study at Vanguard |

| The relationship between IA and business strategy |

| How IA can contribute to competitive advantage |

What is business strategy doing in a book about information architecture? Do they have anything in common? After all, we didn’t have any business strategy courses in our library and information science programs, and it’s safe to say there are very few information architecture courses in the MBA curriculum.

In truth, these two fields have existed independently and in relative ignorance of each other heretofore. This historical isolation is about to change. As the Internet permeates our society, managers and executives are slowly recognizing the mission-critical nature of their web sites and intranets, and this awareness is inevitably followed by a realization that information architecture is a key ingredient for success. Once they’ve seen the light, there’s no going back. Managers will no longer leave information architects to play alone in the sandbox. They’ll jump in and start playing, too, whether we like it or not. The good news is they’ll bring some toys of their own to share, and if we look at this as an opportunity rather than a threat, we’ll learn a lot about the relationship between strategy and architecture along the way.

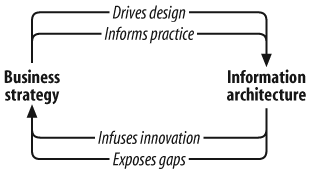

In practice, information architecture and business strategy should have a symbiotic relationship. It’s obvious that the structure of a web site should align with the goals and strategy of the business. So, business strategy (often called “business rules”) drives information architecture. What’s less obvious is that the communication should go both ways. The process of information architecture design exposes gaps and inconsistencies in business strategy. Smart organizations make use of the feedback loop shown in Figure 18-1.

On a more theoretical level, we believe the emerging discipline of information architecture has much to learn from the established field of business strategy. This is not an accidental match-up; the two fields have much in common. Both suffer from a high degree of ambiguity and fuzziness. They’re intangible and don’t lend themselves to concrete, quantitative return on investment analysis. Also, both fields must embrace and influence the whole organization to be successful. Information architects and business strategists can’t afford to work in ivory towers or be limited by narrow departmental perspectives.

And finally, information architecture, along with the umbrella disciplines of experience design and knowledge management, creates new opportunities and challenges for business strategy innovation. As the Internet continues to blow gales of creative destruction[1] through our industries, firms that see technology as their salvation will die. Success will belong to those who understand how to combine technology, strategy, and structure in keeping with their unique position in the marketplace. Information architecture will play a role in this vital and relentless search for competitive advantage.

The Origins of Strategy

Dictionary.com defines strategy as “the science and art of using all the forces of a nation to execute approved plans as effectively as possible during peace or war.” As this definition suggests, strategy has a military history. In fact, its etymology leads us back to ancient Greece, where we find the term “strat-egos” (“the army’s leader”).[2] Early works such as Sun Tzu’s Art of War and Carl von Clausewitz’s On War are still often quoted in the business world.

This explains why the language of business strategy is filled with military terminology—positioning the marketplace as a battlefield, competitors as enemies, and strategy as a plan that must be well executed to assure victory. It also helps to explain why the field of business strategy has been largely dominated by men who project power and confidence and who convincingly build a case that their plan or model or philosophy is the “one best way.” This is a world where indecisiveness is taken as a sign of weakness.

And yet, notice the use of the term “art” in both the dictionary definition and the title of Sun Tzu’s famous text. This is an acknowledgment that business strategy is not pure science. It involves a certain degree of creativity and risk taking, much like our nascent field of information architecture.

Defining Business Strategy

Over the past few decades, Michael Porter, a Harvard Business School professor and successful entrepreneur, has played an influential role in leading and shaping the field of business strategy and our understanding of competitive advantage.

In his brilliant book On Competition (Harvard Business School Press), Porter defines strategy by contrasting it with operational effectiveness:

Operational effectiveness means performing similar activities better than rivals perform them. Operational effectiveness includes but is not limited to efficiency.

He notes that operational effectiveness is necessary but not sufficient for business success. He then answers the question, what is strategy?

Strategy is the creation of a unique and valuable position, involving a different set of activities.

He goes on to explain that “the essence of strategy is in the activities—choosing to perform activities differently or to perform different activities than rivals.” It is this strategic fit among activities that provides a sustainable competitive advantage, which is ultimately reflected in long-term profitability.

Alignment

So how do we align our information architecture activities with business strategy? Well, we need to begin by finding out what strategies our business is pursuing. This can be nearly impossible in large organizations.

As consultants to Fortune 500 firms, we’ve rarely had much access to the senior executives who (we assume) could articulate their company’s business strategy. And the people we’ve worked with often haven’t had a clear idea about the overall strategic direction of their organization and how their web site or intranet fits into that bigger picture. They’ve often been left in the dark.

While we wait for the senior executives and corporate strategists to become more involved in their sites, there are things we can do. Stakeholder interviews provide an opportunity to talk with senior managers. While they may not be able to rattle off a concise explanation of their company’s strategy, these managers can be helpful if you ask the right questions. For example:

What is your company really good at?

What is your company really bad at?

What makes your company different from your competitors?

How are you able to beat competitors?

How can your web site or intranet contribute to competitive advantage?

It’s important to keep digging. You need to get beyond the stated goals of the web site or intranet and try to understand the broader goals and strategy of the organization. And if you don’t dig now, you may pay later, as we learned the hard way. A few years ago, we had an uncomfortable consulting experience with a dysfunctional business unit of a Fortune 100 firm.

We had completed an evaluation of the company’s existing web site and were in the process of presenting our recommendations to a group of senior managers. Halfway through the presentation, the vice president of the business unit began to attack our whole project as a misguided effort. The thrust of her assault can be summed up in the following question: “How can you design our web site when we don’t have a business strategy?”

Unfortunately, we didn’t have the understanding or vocabulary at the time to clearly answer this question. Our ignorance doomed us to a half hour of suffering, as the VP cheerfully pulled out our fingernails. It turned out that her hidden agenda was to get us to write a blunt executive summary (which she could then pass to her boss), stating that if this business unit didn’t have more time and resources, their web efforts would fail.

She was asking the right question for the wrong reasons. We were more than happy to satisfy her request for a brutally honest executive summary (connecting the dots between our IA and their BS), and we managed to escape the relationship with only a few bruises.

The more permanent outcome of this engagement was a personal conviction that information architects need a good understanding of business strategy and its relationship to information architecture.

Strategic Fit

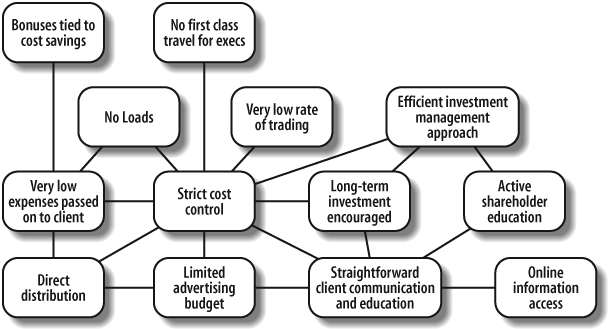

Let’s draw an example from Porter’s On Competition to learn how to connect the dots between business strategy and information architecture. Porter uses “activity-system maps” as a tool for examining and strengthening strategic fit. Figure 18-2 shows an activity-system map for Vanguard, a leader in the mutual fund industry.

As Porter explains, Vanguard is widely respected for providing services to the conservative, long-term investor, and the company’s brand is very different from that of competitors such as Fidelity and T. Rowe Price.

Vanguard strives for a strategic fit between all its activities, from limiting the costs of advertising and business travel to fostering shareholder education and online information access. Low costs and informed investors go hand in hand.

This strategy is no accident. As founder John C. Bogle explains, early in its history, Vanguard established “a mutual structure without precedent in the industry—a structure in which the funds would be operated solely in the best interests of their shareholders.”[3] Noting that “strategy follows structure,” he suggests that it was logical to pursue “a high level of economy and efficiency; operating at bare-bones levels of cost, and negotiating contracts with external advisers and distributors at arms-length. For the less we spend, the higher the returns—dollar for dollar—for our shareholder/owners.”

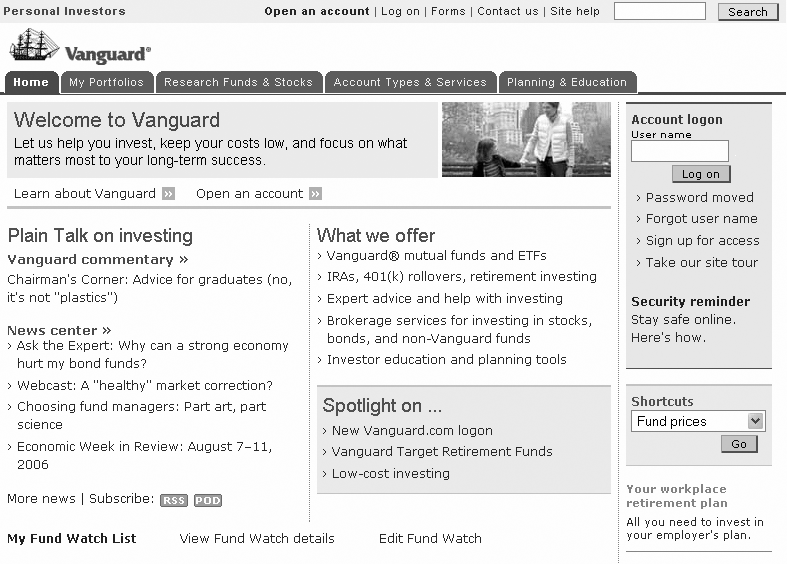

What’s exciting is that this strategy is evident in the design of Vanguard’s web site, the main page of which is shown in Figure 18-3. First of all, notice the clean page with minimal branding. There are no fat logos or banner ads; usability is obviously a high priority. Second, notice the lack of technical vocabulary for which the financial industry is renowned. Vanguard makes an explicit point of using “plain talk.”

And as you explore, you see an emphasis on education, planning, and advice woven throughout the site. Tools like a site glossary, a site map, and a site tour help customers to navigate and educate themselves at the same time.

Vanguard’s web site is distinctive, and that’s how it should be. It’s different by design and reflects the company’s unique strategy. For web sites, structure follows strategy, and the best companies exhibit individuality in both areas. That’s why Dell.com is different from Compaq and IBM, and Landsend.com is different from L.L. Bean and J. Crew.

Rather than copy their competitors and engage in zero-sum price wars, these companies work to understand, leverage, and strengthen their unique positions within their industries. And their web sites are increasingly acknowledged as important strategic assets that can be used to achieve competitive advantage.

Exposing Gaps in Business Strategy

Information architectures should solve problems and answer questions. Consequently, information architects must find problems and ask questions. In our quest to understand how context, users, and content all fit together, we often expose serious inconsistencies and gaps within business strategy, particularly in how it relates to the web environment.

In many cases, the problems are fixable. A company known for excellent customer service has neglected to integrate customer support into its web site. Or a widely respected online bookstore risks violating its customers’ trust by secretly featuring search results for publishers who pay a fee. In a healthy organization, the architect can raise these issues and get them resolved.

In other cases, the problems are symptoms of an organization in real trouble. Consider the following examples, with names omitted to protect the guilty.

A Global 500 company has recently been through a large merger. The U.S. division has a formal, centrally managed, top-down corporate intranet. The European division has several decentralized, informal, bottom-up departmental intranets. Stakeholders on opposite sides of the Atlantic have very different goals and ideas for their intranets. The plan? Design a single integrated intranet to foster the sense of a single, unified company. The reality? Two disparate cultures clashing on a global scale. The tail of information architecture can’t wag this dog.

A Fortune 100 company decides to enter the e-commerce gold rush by throwing $40 million into development of a consumer health portal. After discovering dozens of domestic competitors, they decide to target several European countries, all at once. One tiny problem. They know almost nothing about the health-related information needs or information-seeking behaviors of the people in those countries. And they never get to find out. Eventually the plug is pulled on this out-of-control e-business.

When we find ourselves in situations that feel crazy, it’s human nature to pretend things will work out. We assume the executives really do know what they’re doing and that the master plan will become clear soon. But painful experience suggests otherwise. If it looks crazy, it probably is crazy. Trust your gut. Remember, the executives who develop strategy are human, too. It is not uncommon to find situations where the people involved are aware of major gaps and flaws in the plan, but they’re too afraid or unmotivated to point them out. As the information architect, you may be well positioned to be the one who cries out, “the emperor has no clothes,” and then proceeds to work with the managers, strategists, and stakeholders to put together a more sensible plan.

One Best Way

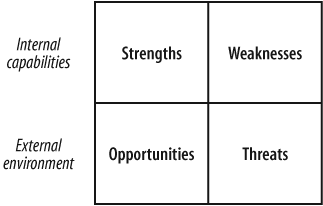

Figure 18-4 illustrates SWOT, the best-known model for strategy formulation. SWOT stands for the analysis of internal Strengths and Weaknesses of the organization informed by the Opportunities and Threats posed by the external environment.

SWOT has been a favorite model of business schools, textbooks, management consulting firms, and senior executives. SWOT analysis can be performed in a classroom or an executive’s office with a small group of people in a short amount of time. These “strategists” or “thinkers” can objectively assess internal capabilities and the external environment, and then deliberately and consciously craft a strategic plan to be implemented by the “doers” of the organization. This model is highly adaptive and can be applied to virtually any type of organization at any time. In many contexts, SWOT has been presented as the “one best way” to formulate a business strategy.

You may have guessed that we don’t agree. And if you’re wondering what all of this has to do with information architecture, stick with us. We’re getting there.

Many Good Ways

In their fascinating book Strategy Safari (Free Press), Henry Mintzberg, Bruce Ahlstrand, and Joseph Lampel approach the subject of business strategy in a manner we as information architects would do well to emulate. The book begins with the fable of “The Blind Men and the Elephant,” (Figure 18-5), which they note is often referred to but seldom known. We decided to follow their lead.

The authors of Strategy Safari proclaim, “We are the blind people and strategy formation is our elephant. Since no one has had the vision to see the entire beast, everyone has grabbed hold of some part or other and ‘railed on in utter ignorance’ about the rest.” Swap “strategy formation” with “information architecture,” and you’ve just described many of the heated debates at our conferences and on our discussion lists.

Strategy Safari extends the philosophy of “many good ways” by describing 10 schools of thought within the business strategy field:

The authors describe an evolution over the past 50 years from the top-down, highly centralized design and planning schools toward the bottom-up, entrepreneurial learning and cultural schools. In today’s information economy, there’s greater recognition that thinking can’t be isolated to the CEO and an elite team of corporate strategists. Knowledge workers must play a role in strategy formation. The doers must also be thinkers, and the plan must be informed by the practice. This evolution is driven by advances in information technology, increased maturity in business management theory, a better-educated workforce, and changing social dynamics.

The authors note that during this 50-year evolution, the business community has desperately embraced each new school as the “one best way,” only to abandon it when something better came along. They explain that just like the blind men, each school is partly right and partly wrong. None deserves a full embrace, but none should be completely thrown aside either.

Understanding Our Elephant

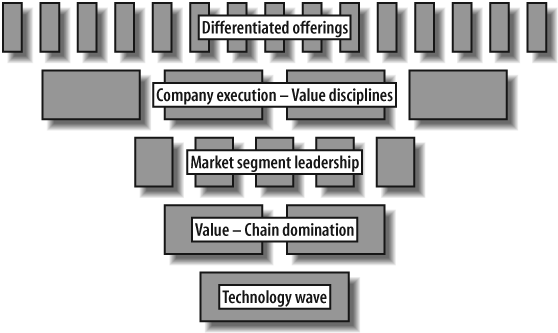

The information architecture community has much to learn from this expansive, honest, multifaceted approach to strategy. We are a young field, and we often resemble the illustration that accompanies “The Blind Men and the Elephant” (Figure 18-6). We have yet to develop our schools of thought. And our elephant is a complex, dynamic, and elusive beast. Building toward a collective understanding of information architecture is exasperatingly difficult.

As we continue to formulate our ideas and methods, we should be wary of those who expound a “one best way.” We should embrace many definitions, many methods, and many facets. We should also be on the lookout for early indicators of trends that suggest new directions and new schools of thought for information architecture. It would be naïve to think our practice has matured in less than a decade.

This is not to say that we haven’t made great progress already. The practice of information architecture has come a long way since the early 1990s. We began with highly centralized, top-down approaches, attempting to leverage careful planning into stable solutions. We did some good work but learned the hard way that change is a constant and surprises should be expected. More recently, we’ve been exploring bottom-up approaches that tap the distributed intelligence within our organizations to nurture emergent, adaptive solutions. The following table compares classic or “top-down” IA to modern or “bottom-up” IA:

| Classic IA | Modern IA |

| Prescriptive | Descriptive |

| Top-Down | Bottom-Up |

| Planned | Emergent |

| Stable | Adaptive |

| Centralized | Distributed |

As we struggle with these ideas, an interesting question arises: do we create information architectures or reveal them?

In Information Ecology, Thomas Davenport and Laurence Prusak have this to say on the topic:

From an ecological perspective, identifying what information is available today and where it can be found is a much better use of architectural design than attempting to model the future. Information mapping is a guide to the present information environment. It may describe not only the location of information, but also who is responsible for it, what it is used for, who is entitled to it, and how accessible it is.

This provocative statement is partly true, but it’s also partly false. Information mapping is a useful approach that more of us should embrace, but it doesn’t negate the value of other approaches. Remember, we are all blind men, and information architecture is our elephant.

Competitive Advantage

The fact that we can’t see the whole picture doesn’t mean we shouldn’t forge ahead. The disciplines of business strategy and information architecture are dauntingly abstract and complex. But we can’t fall victim to analysis paralysis. In the world of business, both disciplines are useless if they don’t contribute to the development of sustainable competitive advantage.

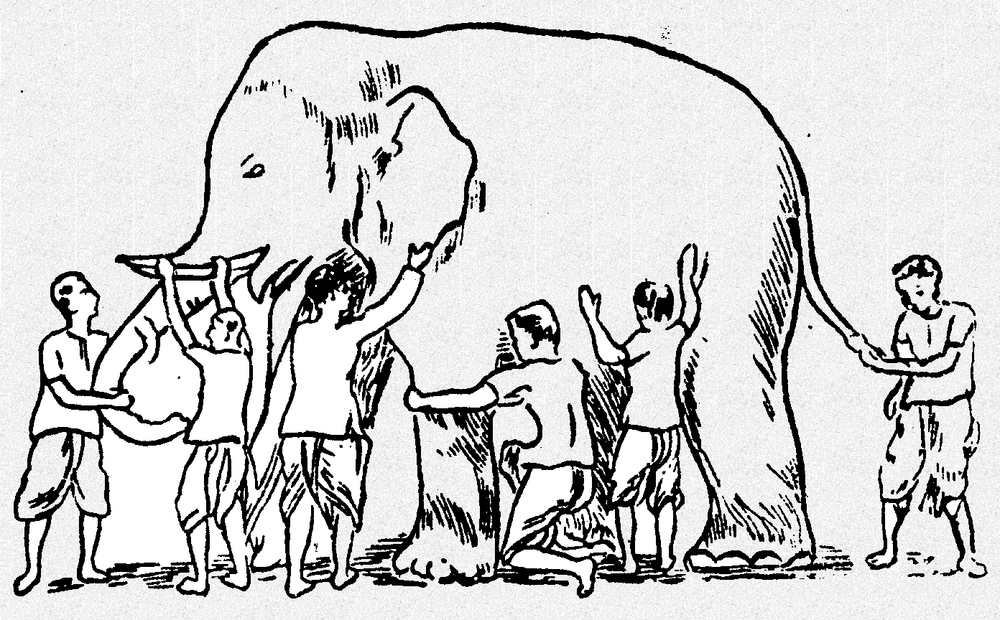

On this vital subject, business strategy can teach us one more lesson. In short, the invisible nature of our work can contribute to our competitive advantage. Geoffrey Moore reveals this hidden opportunity with respect to business strategy. In Living on the Fault Line, Moore presents a competitive-advantage hierarchy to show the multi-layered foundation upon which strategy is built (Figure 18-7).

Moore explains that while most people focus on the top layer of differentiated offerings (e.g., branding and positioning), businesses can achieve lasting competitive advantage only by building from the bottom up.

At the base lies the technology itself, the core of cores. On top of it form value chains to translate its potential into actuality. Atop this evolution lie specific markets . . . Within all markets, companies compete against each other based on their ability to execute their strategy . . . The ultimate expression of this competition, the surface stratum that is visible for all to see, is an array of differentiated offerings that compete directly for customers and consumers on the basis of price, availability, product features, and services . . . In technology-enabled markets, corporations, like tall buildings, must sink their foundations down through all the strata to secure solid footing in competitive advantage.

While the media pundits and water-cooler jockeys rant and rave about branding and positioning, the strategic decisions with long-term implications are happening beneath the surface, invisible to the outside world and to many corporate “insiders.” The invisible nature of this strategy work confers greater gains to leaders and thwarts copycat competitors.

The End of the Beginning

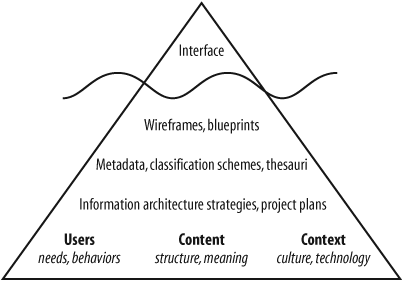

As information architects, we can also use invisibility to our advantage. There is no question that our discipline suffers from the iceberg problem, as illustrated in Figure 18-8. Most of our clients and colleagues focus on the interface, without appreciating the underlying structure and semantics.

Savvy designers know to look beneath the water line, understanding the importance of blueprints and wireframes to site development. But few people, even within the web design community, realize the critical role the lower layers play in building a successful user experience. This ignorance of deep information architecture results in short, superficial, and often doomed projects.

Those who recognize the need to build structures from the bottom up have an immediate advantage over those who skim along the surface. And because this structural design is hidden from the outside world, these early adopters get a big head start. Once competitors see what the Episcopalians call “the outward and visible signs of inward and spiritual grace,” it’s often too late. By the time Borders Books & Music realized the power of Amazon’s user experience, they were already years behind.

But invisibility doesn’t automatically confer sustainable advantage. In today’s fast and fluid economy, easily duplicated best practices spread like wildfire. This is why companies can no longer look to technology for their salvation. By lowering the barrier to entry and fostering open standards, the Internet has created a more level playing field.

Michael Porter says it best in a Harvard Business Review article:[4]

As all companies come to embrace Internet technology, the Internet itself will be neutralized as a source of advantage. Basic Internet applications will become table stakes—companies will not be able to survive without them, but they will not gain any advantage from them.

Today’s cutting-edge technology is tomorrow’s commodity. If it can be copied, it will be copied. Porter goes on to explain:

To gain these advantages, companies need to stop their rush to adopt generic “out of the box” packaged applications and instead tailor their deployment of Internet technology to their particular strategies. Although it remains more difficult to customize packaged applications, the very difficulty of the task contributes to the sustainability of the resulting competitive advantage.

That last line resonates strongly in the context of information architecture. In effect, we can transform the invisibility and difficulty of our work from a liability into an asset. The possibilities for aligning information architecture and business strategy to produce sustainable competitive advantage are exhilarating.

We have much to learn, and we’ve only just begun. When we look back many years from now, we will chuckle at the foolishness of our earliest efforts on the Web. We will wonder how we ever thought that information architecture and business strategy could exist independently. We haven’t yet figured out all the answers, but at least we’re starting to ask the right questions.

As Winston Churchill once said, “This is not the end. It is not even the beginning of the end. But it is, perhaps, the end of the beginning.”

[1] The concept of “creative destruction” was first formulated by economist Joseph Schumpeter (1883-1950).

[2] “The Historical Genesis of Modern Business and Military Strategy: 1850–1950,” by Keith Hoskin, Richard Macve, and John Stone, http://les.man.ac.uk/ipa97/papers/hoskin73.html.

[3] John C. Bogle, “The Vanguard Story,” http://www.vanguard.com/bogle_site/october192000.html.

[4] Porter, Michael. “Strategy and the Internet,” Harvard Business Review, March 2001.