Chapter 21. evolt.org: An Online Community

| How incentives can serve to drive an economy of participation among content creators and consumers |

The building of online communities has been going on since the Web began. Some have succeeded, but most have failed spectacularly. Yet again and again, the allure of thousands of paying customers happily discussing the benefits of a company’s latest widget makes even the most hardboiled and pragmatic businesspeople throw caution to the wind. Fanning the flames of the online community fire were all sorts of new and intensely marketed community-enabling technologies, such as chat applications, that promised that “if you build it—with our technology, of course—they will come.”

Clearly, online communities require more than cool tools to succeed. Technologies enable people with shared interests to converse and exchange ideas, but it’s up to those people to contribute interesting and relevant information, stay on topic, be patient with one another, and police themselves when things get out of hand. Every community is unique in who it allows to join, how it welcomes and initiates new members, what types of events and milestones it promotes, and what types of behaviors it honors. So it’s not grandiose to claim that each successful online community truly has its own culture.

Cultures and communities don’t just happen; they require careful nurturing. On the other hand, they wither when overmanaged. A well-designed information architecture can help balance these two extremes, flexibly encouraging freedom of expression and action while organizing and structuring content for better findability. And where other architectures have to fit within a context, an online community architecture creates that context—it is often the only place where its members meet. In effect, online-community information architecture is the ultimate exercise in designing for context. This case study describes evolt.org, a real live online community that is grappling with, and succeeding at, providing and nurturing the context for its members.

evolt.org in a Nutshell

What is evolt.org? That’s simple—it’s explained at the bottom of each page in the site:

evolt.org is a world community for web developers, promoting the mutual free exchange of ideas, skills and experiences.

What “evolt” means: “evolt” combines the best elements of evolution, revolution, with a bit of voltage thrown in for good measure. “evolt” embodies our goals and enthusiasm!

The evolt.org site provides an interesting case study in online-community information architecture—its membership has grown quickly in its short life, and yet the site has hung together despite its distributed membership, rapid growth, competition, reliance on volunteers, noncommercial approach, and other factors that can potentially cause trouble. We learned some interesting lessons from evolt.org and its members, who have taken a novel and completely nontraditional approach to information architecture.

Architecting an Online Community

Online communities aren’t built upon compulsory participation; to succeed, they must attract members who are already busy doing other things. And sometimes online communities compete with other communities that are doing much the same thing.

evolt.org, for example, is focused on web development. As you might guess, there are many other communities that share the same focus. So the evolt.org folks must be doing something right—in five years’ time, they’ve built four active mailing lists, the largest of which (“thelist”) has over 3,000 members. And the evolt.org web site has over 24,000 registered users. These growing numbers are impressive, even more so when you consider evolt.org’s budget, which is minute. Volunteers contribute their time and passion, and they’ve cobbled together a few servers to make this work.

Obviously, passion and today’s incredibly cheap and powerful information technologies are a potent combination. But they aren’t enough to guarantee success; an environment must be created to tie them together. Someone has to play God, setting up the rules and infrastructure that create an environment that becomes self-sustaining, and where people join in and participate. And that’s where information architecture comes in. Information architecture provides much of the structure that ties together the people, passion, content, and technology in one cohesive place.

So how exactly does information architecture figure into evolt.org?

The Participation Economy

The major challenge faced by every online community is how to get people to participate. Participation requires a balance of give (creating content) and take (consuming content). It’s difficult to ensure reciprocity between givers and takers; it’s often human nature to lurk and learn, while creating good information takes time and hard work. If everyone consumes and no one produces, online communities fail. Those responsible for online communities therefore have a harder job than Ben Bernanke (the head of the U.S. Federal Reserve Board). Beyond tweaking economic performance, they have an even larger job: to create the economy from scratch. And since they can’t force people to participate, a healthy online-community economy must therefore err in the direction of free-market principles—enabling, not overmanaging—the creation of content in a way that keeps up with its consumption.

Information architecture comes into play here in two ways. First, it provides a critical set of rules and guidelines that make up part of the economy’s infrastructure, much in the same way that the international banking system structures transactions in the global economy. So information architecture is a key part of “setting up” an economy.

Second, information architecture can be used to tweak levels of “transactions” in the participation economy, much like the Federal Reserve Board’s adjustments to interest rates can invigorate or cool down economic activity. Information architecture greases the participation economy by supporting different levels of content creation that fit with human nature, and by “monetizing” that participation so that members better understand what their content creation—and consumption—is worth.

Supporting Different Levels of Participation

Some sites put up a huge wall that must be scaled in order for users to participate. For example, they may require all sorts of personal information from participants before they’re “allowed in.” This speakeasy model may work in unique situations, but it generally fails in today’s competitive environment of plentiful community venues and sources of content. A better approach is to accommodate the different levels of participation sought by many sorts of people, ranging from the quiet lurkers to the hyperactive gadflies.

evolt.org supports different levels of access to its content and other resources. Anyone, member or not, can be involved in evolt.org, but higher levels of participation are accorded to members, and even higher levels to administrators. These social strata are detailed in Table 21-1.

| Class | Participation level |

| Anyone | Allowed abilities:Search and browse the entire site and mailing list archives.Read articles.Download browsers from the browser archive.Submit items to the directory of web development resources. |

| evolt.org members | Can do all of the above plus:Subscribe and post to any of the discussion lists.Rate and comment on articles.Contribute articles for publication in evolt.org.Create an entry in the member directory.Search the member directory.Apply for a members.evolt.org (“m.e.o.”) account, which provides disk space and tools for experimentation. Make suggestions about how to improve the lists or the site.Have input on decisions affecting evolt.org through participating in “theforum” discussion list. In certain cases, implement changes to the site and its back end. |

| evolt.org administrators | Can do all of the above plus:Edit and approve/deny submitted articles.Answer messages submitted by users.Write FAQ articles. |

Although this scheme is by no means revolutionary, it does set in place a system of “classes” and a logical migration path that taps people’s desire to be “upwardly mobile.” Nonmembers get an initial taste of the site that may encourage them to increase their level of participation over time.

More classes could be developed, but that would make for too complex and weighty a caste system. evolt.org has judiciously chosen to keep things simple so that users understand which class they belong to and where they can go from there. And the rite of passage from “anyone” to a decision-making member is quick and relatively painless (no tattooing, branding, or other forms of hazing are required).

Capital in the Economy

Perhaps even more interesting is the way that participation is “monetized.” The evolt.org economy runs on many types of “money” that take on two major forms: payments made by producers, and payments received by consumers. More specifically, evolt.org’s “payments” are transacted through such commonplace actions as posting to a discussion list, writing an article, or creating a personal directory entry, as we describe next.

Discussion list postings

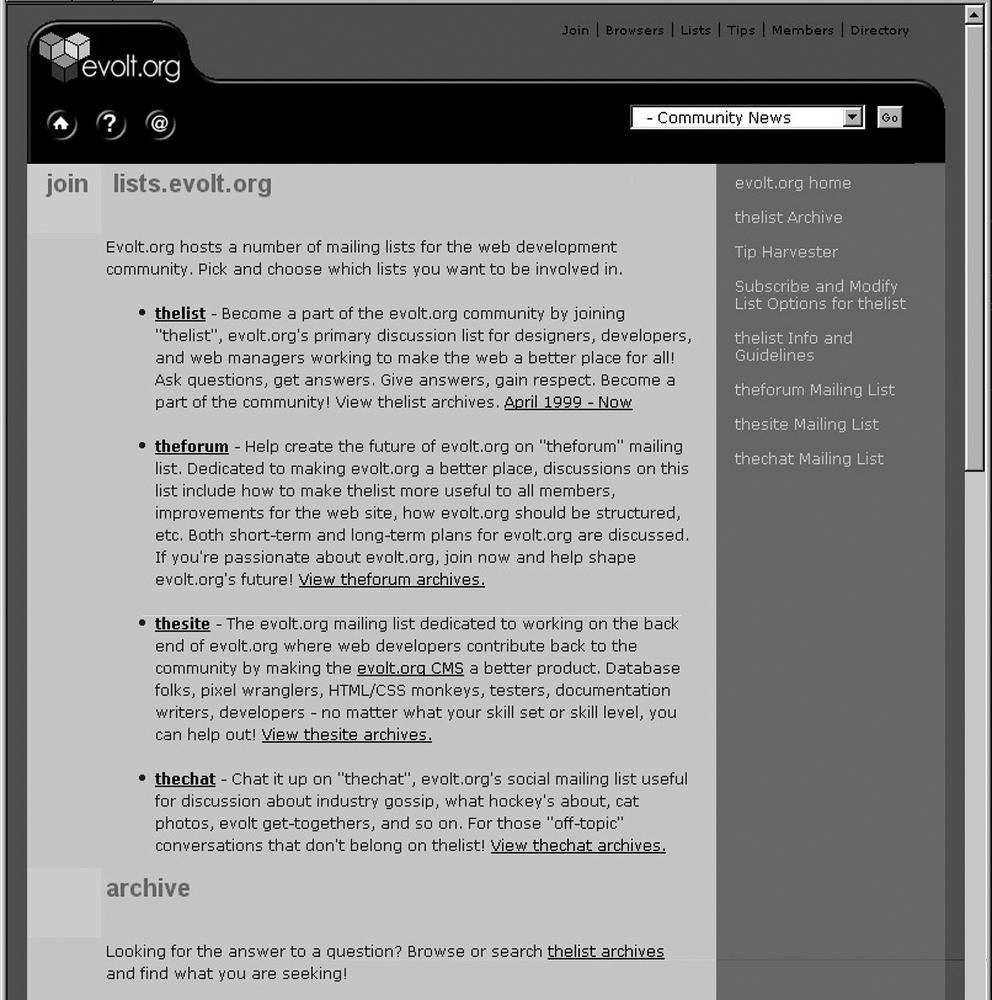

When someone posts a question, answer, comment, or idea to an evolt.org discussion list, she isn’t necessarily conscious of conducting a transaction in evolt.org’s participation economy. In fact, such postings are essentially the backbone of the economy, as most people come to evolt.org for the discussions. And, because evolt.org supports four major discussion lists—each addressing different aspects of web development and the management of evolt.org itself—the needs of many types of users are addressed. “thelist” is where evolt.org’s raison d’être—web development—is discussed. “theforum” and “thesite” are oriented more toward building and improving evolt.org itself. And “thechat” is the place to take inevitable off-topic conversations. (See Figure 21-1.)

Tips

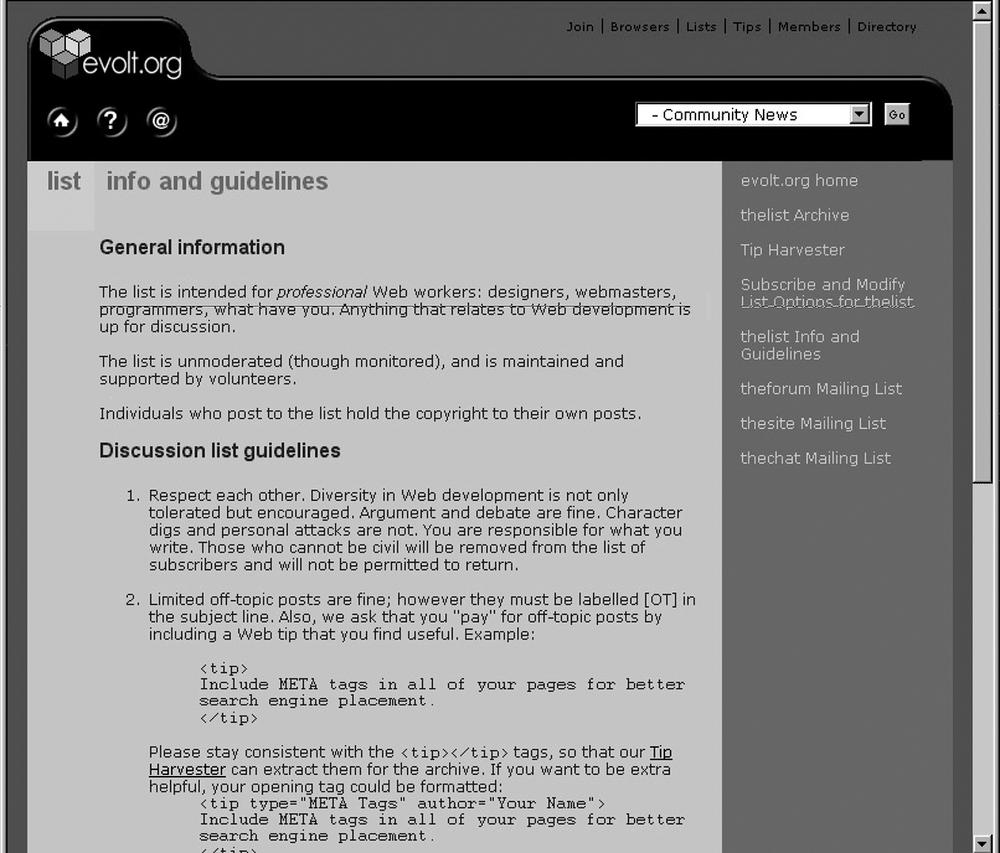

But while evolt.org encourages contributions to its discussion lists, it also must balance quantity with quality. Low signal–noise ratio is probably the leading cause of list collapse, so evolt.org uses a variety of methods and guidelines to maintain quality in its discussion-list postings (see Figure 21-2). While it can’t force posters to stay on topic, it does ask them to prefix their subject lines with the warning “[OT]” (for Off-Topic) when necessary. That way, a reader can quickly scan a subject line and spot an off-topic posting without having to read the full posting.

More ingeniously, evolt.org employs a policy that makes those responsible for off-topic postings “compensate” the community. Negligent authors are asked to include “tips,” consisting of useful web development-related wisdom, in their off-topic postings. They typically comply; in fact, many authors compose tips just for the sake of it.

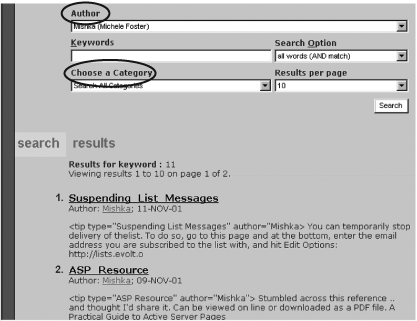

Authors must mark up their tips in a way that enables evolt.org’s automated “Tip Harvester” to index them for future use by the community. This is done with a simple open tag (<tip>) and close tag (</tip>). Tip authors are also encouraged to make use of additional markup options, such as <tip type=“...”> and <tip author=“...”>. This markup supports impressive searching capabilities for a site that’s not tightly controlled (Figure 21-3).

Economies based on compulsion don’t survive for long. And evolt.org really doesn’t have the infrastructure, much less the desire, to police communications and punish violators. That’s why tips are so important—after all, it’s a given that we can’t always stay on topic, and it’s difficult to participate in a community without revealing any of your personal thoughts and feelings. Tips allow members to make up for their off-topic postings by contributing capital elsewhere in the community. In effect, tips are an examples of transactions in evolt.org’s economy; they enable members to “pay” for their participation. And what’s considered a plague in many other community discussion lists is transmogrified into a win–win situation in evolt.org’s online community.

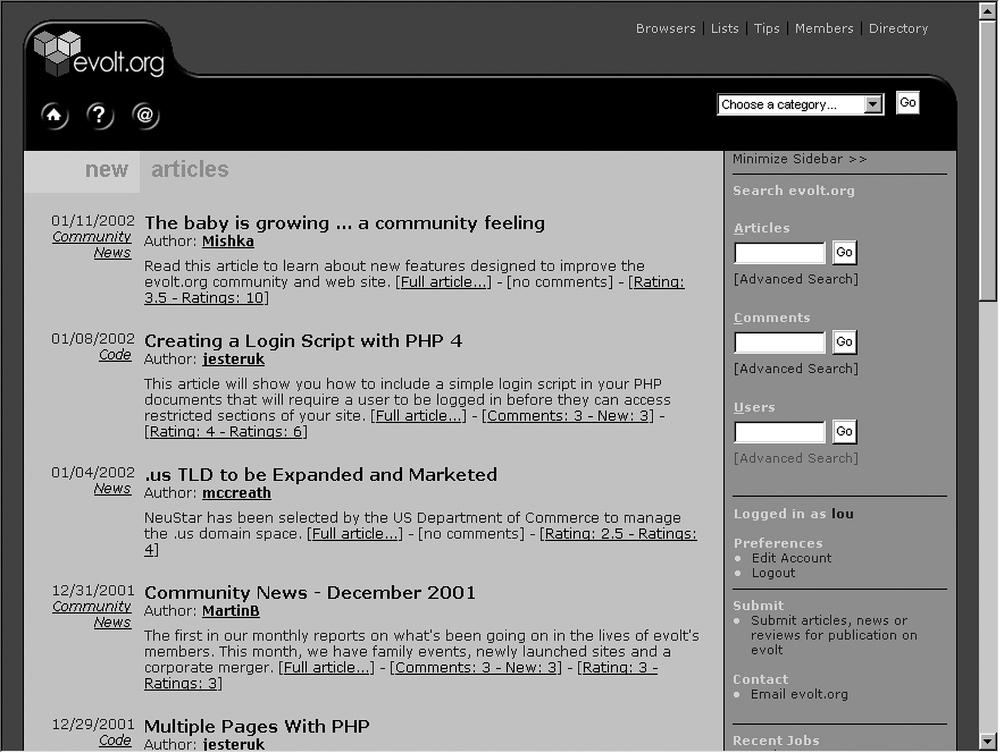

“Published” articles

Articles represent a major investment in the evolt.org economy, both for authors, who are expected to put significant effort into writing them and receive recognition in return, and for evolt.org itself, which is often measured by the quality of such articles. Additionally, evolt.org accords articles prime real estate on the site’s main page, as shown in Figure 21-4.

And evolt.org makes the investment equally risky for authors by prominently featuring readers’ comments and ratings. This enables other readers to quickly determine how their peers are reacting to a particular article. These comments and ratings help evolt.org assure a degree of quality in its articles. Table 21-2 further explores the capital being exchanged in this content “transaction.”

| Transactor | “Pays” | “Receives” |

| Authors | Articles | CommentsRatingsRecognition |

| Readers | CommentsRatings | ArticlesGuidance from other readers’ comments and ratingsParticipatory role in the community; sense of ownership |

| evolt.org | Valuable screen space | Assurance that reader comments and ratings will prevent the contribution of low-quality articles |

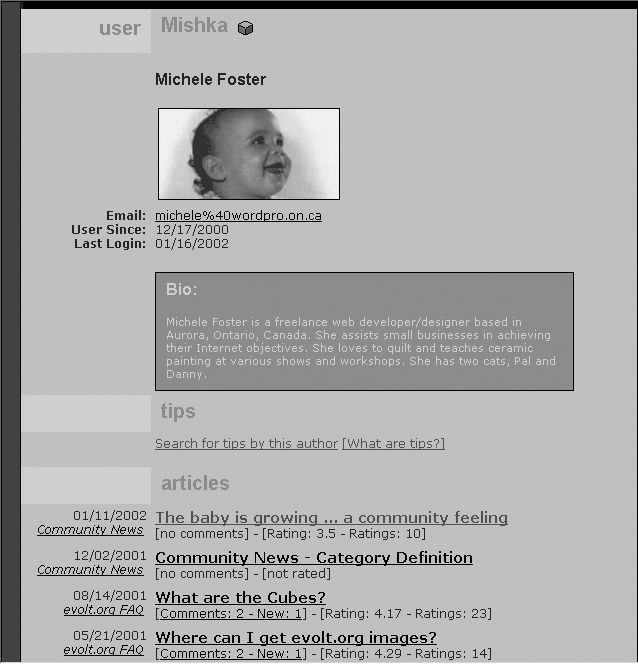

As authors create content over time, they can accrue more capital. This is reflected on article pages, where “cubes” and other cumulative information are displayed, as well as on authors’ biographical sketches in the evolt.org member directory.

Cubes are simply graphical representations of how prolific an author’s output is. The cube in Figure 21-5 shows that Mishka has authored one to five articles. The sidebar on the right shows us that she has in fact written exactly five articles, which have been rated 54 times at an average score of 3.86 (on a 1–5 scale). And there’s a cute photo to boot.

This information is useful to readers, who can quickly judge the quality of the author’s output; the photo and links to email address and other author information serve to personalize her. By making authors more familiar to readers, evolt.org’s information architecture may help increase the sense of community that reading an article brings. It’s also helpful to authors, whose initiative to contribute articles (not to mention their self-esteem!) may be driven by knowing that evolt.org colleagues are reading their articles, posting comments, and reacting strongly enough to rate the articles. (Writing with an audience in mind is a wonderful author motivator.)

Biography listings

Should readers wish to learn more about an author, or if members want to know more about one another in general, evolt.org provides more detailed biographical information in its member directory. Directory pages include member-entered information (e.g., email address and brief bio), and automatically display their contributed tips and articles with reader comments and ratings (Figure 21-6). Although evolt.org hasn’t chosen to do so, it might also be useful to link to a member’s recent discussion-list postings.

New ventures

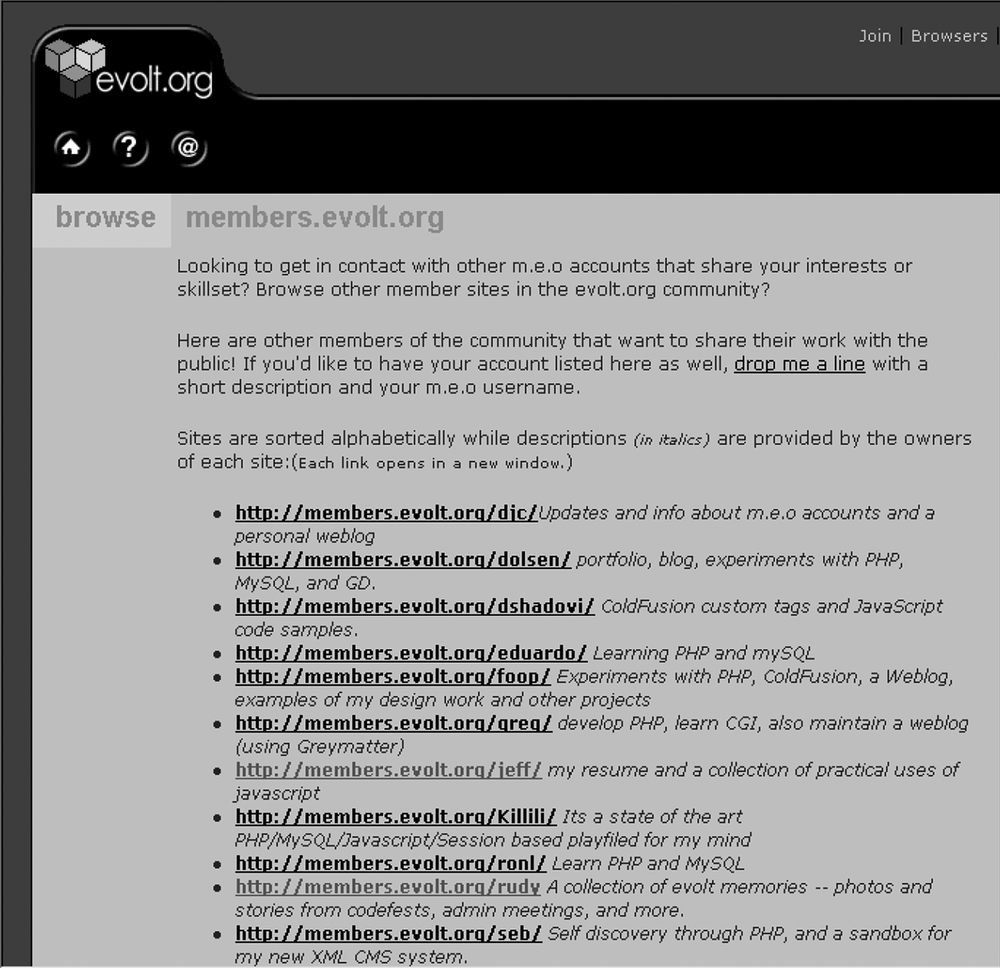

One of the great benefits of this era of cheap and powerful information technology is that, well, information technology is cheap and powerful! Cheap and powerful enough that a free community site like evolt.org can make it available as a sort of “venture capital” to its more entrepreneurial members.

This is the goal of members.evolt.org (m.e.o.): it serves as a development environment or “sandbox” for evolt.org members. It provides members with access to such web development essentials as ColdFusion, MySQL, Perl, PHP, Python, server-side includes, JSP and ASP capabilities, FTP, POP3 email, and, of course, disk space (currently 15 Mb per person). Instead of serving as an ASP or hosting service for operational sites, m.e.o. allows members to hone their web development expertise by working on experimental projects. Figure 21-7 shows a list of the projects that were being developed in the m.e.o. skunk works (which is unfortunately now defunct).

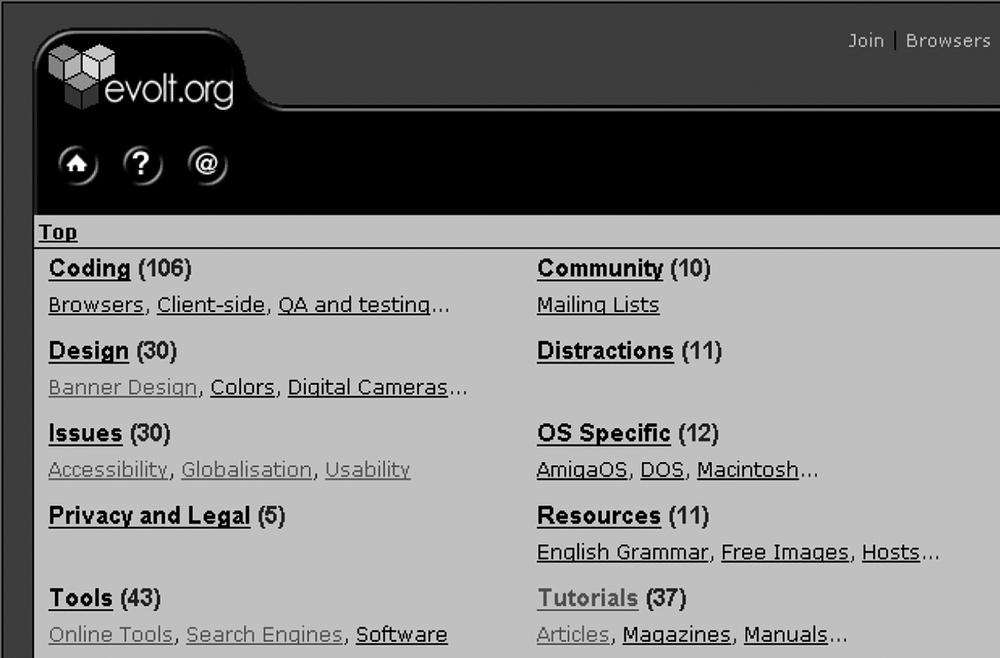

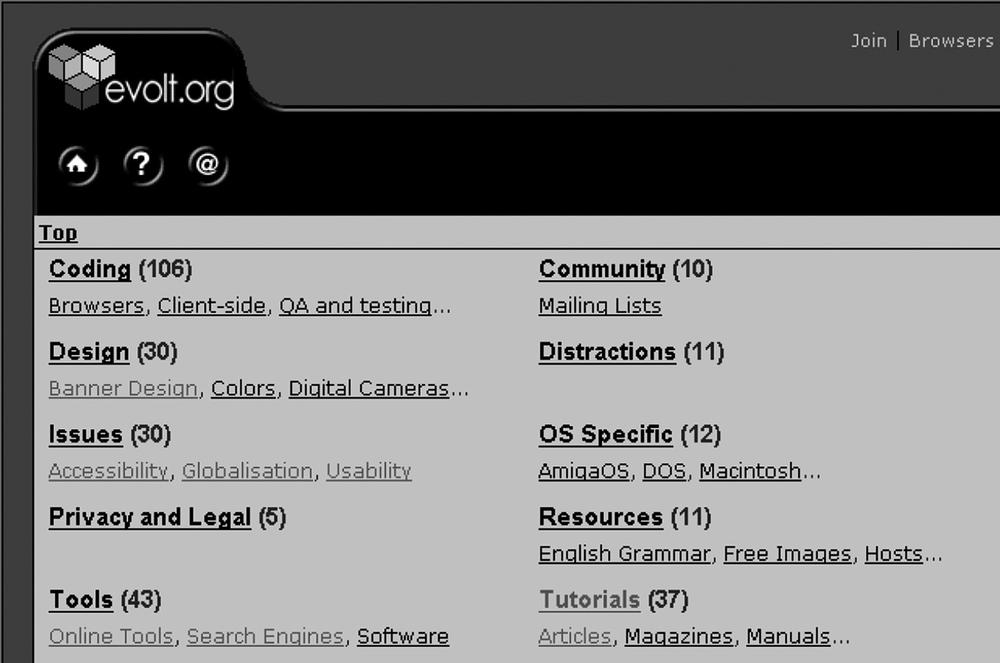

What does evolt.org get out of making all these goodies freely available? Besides goodwill, m.e.o. also inspires members to be entrepreneurial—to develop new concepts that might serve the greater good of the evolt.org membership. One evolt.org administrator describes m.e.o. as akin to a “government grant for scientific research,” and that investment has started to pay dividends. One member’s coding experiment has evolved into a live directory that allows members to contribute to a growing collection of web development resources (see Figure 21-8).

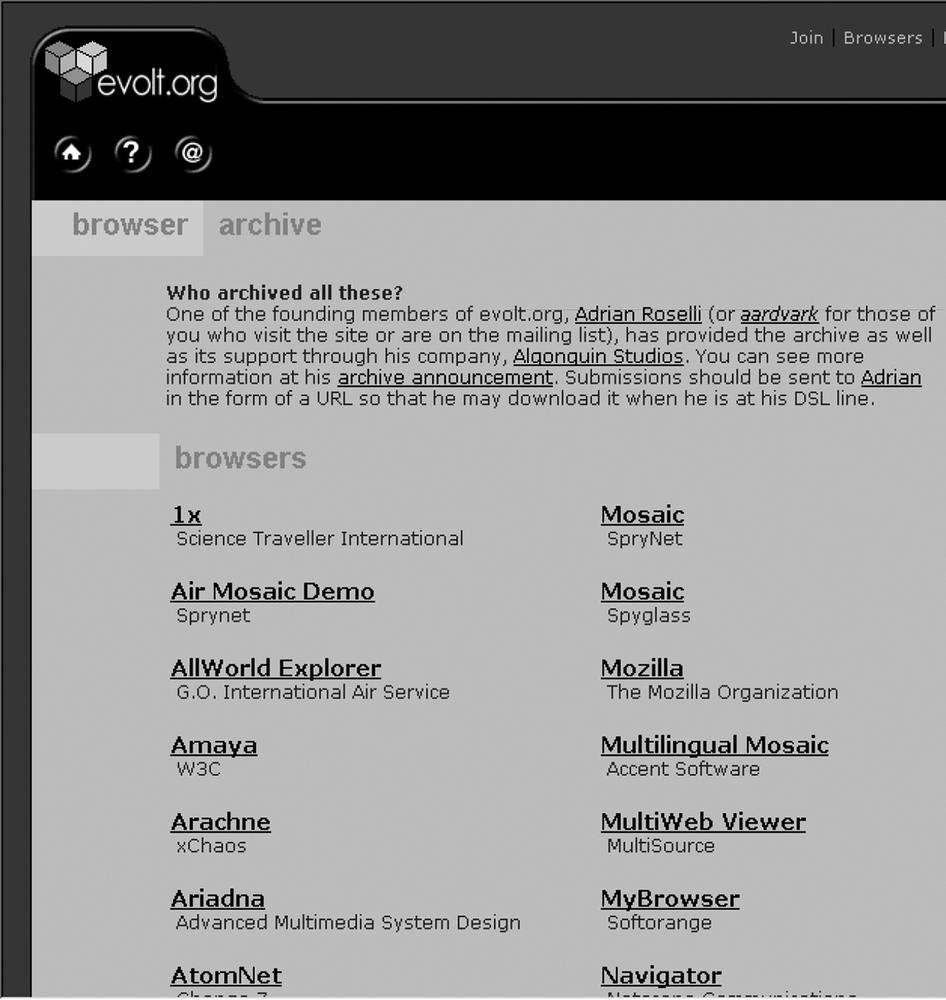

The evolt.org community also spawned the creation of a well-regarded archive of browsers, shown in Figure 21-9. The Browser Archive is handy for web developers who want to download copies of various browsers for testing their designs.

Decision-making

Decisions regarding evolt.org’s direction are another type of transaction in the evolt.org economy. Initially, the site placed decision-making in the hands of administrators, many of whom were founders of the community. In their Godlike role, admins created the rules, roles, economy, and infrastructure that allow evolt.org to function on its own.

As the community matured and the maintenance workload increased, decision-making became more democratized and was placed directly into the hands of evolt.org members. Two discussion lists were created specifically for decision-making: “theforum” (for the community’s general direction and policy) and “thesite” (for decisions and work on the site’s “back end”). This democratization and expansion of decision-making was possible and sensible once the size of the community and its members’ sense of ownership and responsibility had reached a critical mass. In effect, evolt.org’s creators set up the community’s infrastructure and waited for members to “move in” and achieve the ability to self-police their community. When they moved in and began to feel comfortable and invested in the place, they could be expected to take on responsibility for guiding evolt.org’s future.

In this context, decisions are made informally: the community’s size renders decision-making by consensus infeasible, and formal majority voting cumbersome. Despite this informality, the system works; members are neither shut out of decision-making nor overburdened by it.

And despite shedding much of their decision-making power, admins still play an important role—they approve or deny article submissions, and they have the ability to edit those submissions. They also answer user questions, help write the site’s FAQs, settle ties, and occasionally represent evolt.org in public settings. This broader set of roles is the most demanding of any in evolt.org; however, it’s also considered an honor since not everyone gets to be an admin. To be admitted to the “club,” one must be invited by its current members. The honor typically falls to long-time members who have made active and visible contributions to the community.

How Information Architecture Fits In

In this discussion of evolt.org, we haven’t covered much in terms of the basic nuts and bolts of information architecture; we haven’t shown a single blueprint or wireframe, or discussed how users might search and browse the site.

In fact, evolt.org’s information architecture is extremely simple, and perhaps not all that interesting if examined in a vacuum. However, it is extremely interesting to see how the site’s information architecture enables the community to create and share content—this, after all, is the ultimate challenge in online-community sites. The architecture’s minimalism is what makes it superlative.

The information architecture simply doesn’t get in the way of people who wish to create content, but it does actively support getting that content in all sorts of volumes, sizes, and degrees of structure. It displays content captured elsewhere—ratings, comments, biographical information, and so on—in new settings, such as member directory entries, and in new forms, such as cubes. It provides an open canvas for experimentation that leads to innovation.

Therefore, evolt.org’s information architecture has a lot to do with many of the characteristics of a successful online community. It shows how and why one might participate, provides valuable original content, helps promote a sense of ownership among its members, makes sure that contributors are recognized, and taps and repays members’ philanthropy and sense of altruism.

Of course, this isn’t to say that evolt.org’s information architecture couldn’t be improved. Like any information architecture organically developed by a geographically disparate community, evolt.org’s silos could be better integrated from the bottom up. And certain areas of the site haven’t yet found an “economic model” to ensure their survival.

Cracking the Nut of Integration

evolt.org’s information architecture features some major silos:

Discussion lists and their respective archives

Tips and their archive

Articles

The member directory

The web development resource directory

The browser archive

The developmental area (m.e.o.)

These are reasonably well integrated. For example, articles and tips link to their author’s entries in the member directory; additionally, articles embed biographical content directly in the page. Tips are ingenious in that they are created specifically to be used again and again, either by being read on the fly or accessed from the tips archive.

On the other hand, there are additional opportunities for further bottom-up integration. For example, the discussion-list postings don’t link to their authors’ entries in the member directory, and vice versa. The discussion postings are an incredibly rich resource, but it’s a bit of a hassle to find out who’s responsible for them; you’d need to go to the evolt.org site, log in, and search the member directory to find out the source of that brilliant posting. Threads aren’t treated as objects that can be searched or browsed. The discussion archives themselves aren’t easily searchable, and it could be useful to search them all together, instead of one by one.

Integration is also tricky from the top down. While the site’s primary organization scheme (Join, Browsers, Lists, Tips, Members, and Directory) works well for now, it probably won’t scale well as new content areas spring from the m.e.o. skunk works.

Fit Enough to Survive?

Integration aside, the other major architectural challenge that online communities face is ensuring that each of their components has a sufficiently robust “economic model.” The best example of this concern can be found in evolt.org’s resource directory (Figure 21-10). Created and maintained by one person, the Directory accepts suggestions for resources to include from anyone who wishes to submit them. The obvious concern is that if not enough resources are submitted, the Directory will have limited utility. If too many are submitted, the maintainer will drown in a sea of cataloging and classification.

How should this problem be addressed? Typically, evolt.org would look to broaden participation by incenting other members to help manage the Directory. However, developing controlled vocabularies, identifying resources, and consistently indexing and classifying content are not easy tasks for lay people (especially volunteers) in distributed environments. Controlled vocabularies in particular require a high degree of central control, something that may not be practically (or philosophically) in accord with how evolt.org works.

The Yahoo! directory faced similar challenges in 1996, but Yahoo! had ample venture capital to fund its efforts. Despite that, the Yahoo! directory’s quality began to erode over time, and in fact, most people now use Yahoo! for services other than its directory. The Open Directory Project, staffed completely by volunteers, has also encountered similar scaling problems. It will be difficult for evolt.org to solve this one; online communities don’t typically spawn or operate by approaches that rely on significant central control. Perhaps this would be a great place to apply user tagging—folksonomies, à la del.icio.us and Flickr. Certainly, metadata control would be sacrificed, but a more sustainable model—one in line with evolt.org’s philosophy—would take its place.

The “Un-Information Architecture”

Despite these concerns, evolt.org and its information architecture are impressive and successful. We should celebrate its very existence and also congratulate its founders on developing a flexible model that is likely to survive through the next generation of administrators.

Yet the process by which evolt.org took shape is anathema to “traditional” information architecture; there was minimal planning, formal process, or methodology. The whole approach has a “throw it against the wall and see what sticks” flavor to it.

And you know what? That’s OK.

When a site operates on the goodwill of volunteers who create its infrastructure and populate it with content, it’s hard to get them to follow a plan. Nothing about evolt.org—including its information architecture—can be forced. Accommodation, flexibility, and the willingness to experiment (and to live with those experiments!) are what drive the information architecture, not the other way around.

So, like the site itself, the architecture is a work in progress. Someone comes up with a good idea and floats it, others encourage him to try it, and suddenly there’s a new section of the site. Integration with the rest of the site comes afterward, if at all. This constant morphing is the case with more than just the actual site architecture; it applies to the people involved—the volunteers and decision-makers—and the policies as well.

Transitional architectures can succeed only if the community is true to its goal of broad participation. In an environment where ideal methods such as contextual inquiry and content analysis are too expensive to be practical, volunteers must be counted on to take an active role in coming up with ideas that contribute to a better information architecture in their own way. Members ultimately design the information architecture for one another. Like the participatory economy, participatory information architecture will ultimately be the reason why sites like evolt.org survive and prosper.