Stage 0

Strategic Definition

Chapter overview

During this initial stage the tasks and information necessary to determine the feasibility, aspirations and outcomes of the project will be collated and reviewed. Assessing Feedback from similar projects, best practice research, Post-occupancy Evaluations and performance of systems in use will outline the principles required to develop and finalise a strategic appraisal. The Strategic Brief will record this approach and provide a solid foundation from which the development of the project, if appropriate, can be progressed.

The key coverage in this chapter is as follows:

Stage 0 is a new stage, during which the viability of a project is assessed, typically before a formal response is developed and large amounts of time and effort have been expended. The project team will focus on the development of the Strategic Brief; an ‘ends-driven’ document that succinctly sets out the client’s key outcomes and achievable objectives, including:

The Strategic Brief will not necessarily be a large document, but it will establish the appropriate information required to:

The final document will respond to the client’s Business Case, outlining a robust understanding of the key processes and requirements. The Core Objectives of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 at Stage 0 are:

At this stage, the Core Objectives are structured solely in support of the Strategic Brief, with much of the information developed from client-specific requirements, although other studies, such as precedents, research, performance data and Feedback, should be reviewed to test the Business Case, especially if the client is new to the design process. This approach will ensure that the Initial Project Brief can be developed appropriately within Stage 1 alongside any Feasibility Studies and prior to the Concept Design. Some of the most important project decisions are made during this stage, prior to the commencement of any design work, and it is highly likely that much of the success and value of the project will be determined during these early explorations. For example, the strategic appraisal may highlight that there is no need for a project at all, with the client’s requirements being achievable through an alternative route, or that a refurbishment approach is appreciably more viable and appropriate than a new-build facility. These early decisions are significant in defining the project direction and will help to minimise effort wasted on developing inappropriate briefs and concept designs. Given that these early decisions will have a fundamental impact on subsequent developments, a comprehensive evaluation of the project’s potential needs to be completed in order to demonstrate where value can be added to a client’s operations and aspirations. This strategic appraisal will need to address:

A robust understanding of these issues will enable the Initial Project Brief to be developed appropriately at the next stage, which will provide the basis from which any Feasibility Studies and the Concept Design can be developed. The Business Case for a project is the rationale behind the initiation of a new building project. It may consist solely of a reasoned argument. It may contain supporting information, financial appraisals or other background information. It should also highlight initial considerations for the Project Outcomes. The Business Case might contain:

The contents will vary from project to project; however, it is crucial that any drivers or influencing factors are recorded and signed off by the client. In summary, it is a combination of objective and subjective considerations. The Business Case might be prepared in relation to, for example, appraising a number of sites or in relation to assessing a refurbishment against a new-build option. The Strategic Definition stage should be considered as ‘beginning with the end in mind’. It is inherently dependent on the information and outputs collected from similar projects while they are in use. Collating this data can equally be considered as ‘ending with the beginning in mind’. This cyclical approach to understanding Project Outcomes and Feedback is essential to setting out the aspirations and performance requirements within the Strategic Brief. Feedback reviews are an important task: they will help to ensure that the Project Outcomes reflect both the client’s requirements and best practice. The process requires an understanding of a wide range of strategies, issues and approaches that will ultimately underpin the design information developed during the subsequent stages and the overall operation and performance of the project when ‘In Use’. Feedback reviews can include assessments of:

Understanding how these approaches performed on projects of a similar use, type and scale may influence the overall design approach and the strategic performance targets, outlining what ‘best practice’ considerations should be applied. Reviewing these strategies can also help to define the key Project Outcomes in terms of quality, performance and environmental aspirations. The iterative nature of the information review process, of learning from the end to define the beginning, is critical to the structure of the RIBA Plan of Work 2013, allowing successful objectives, tasks and information to be measured and assessed. Project Outcomes Using Project Outcomes to develop the brief represents a shift from physical, functional and budgetary requirements, to a focus on how a project can enhance aspirations, experiences, operation and performance for the client and users. Successful outcomes might include improvements to outputs and productivity in commercial environments, increased turnover and sales for retail schemes or improved personal development within educational facilities. The Value Handbook: Getting the most from your buildings and spaces, produced by the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment (CABE), outlines six specific value definitions:

These are detailed in table 0.1.

Using these value definitions in association with operational performance requirements can inform the Strategic Brief, in addition to helping evaluate the overall success of the completed project. Analysing and assessing all the different forms of Feedback will help to outline best practice guidance to particular building sectors and types; however, these forms of feedback should always be assessed and measured within the context of their specific project in order to ensure they do not adversely impact other strategic requirements and aspirations. Economies of scale, environment, context, brief, budget and performance should all be assessed to test the viability of best practice approaches; for example, solar control systems found to be exceeding performance targets on a small project might not be suitable or as efficient on a larger project within the same sector.

Best practice information Best practice information documents a solution or an approach that has consistently achieved or exceeded its desired outcome/performance and can be used to develop a similar approach or as a benchmark against which to test and assess the performance of other systems. Post-occupancy Evaluation (POE) and building performance evaluation (BPE) utilise direct operational and user experiences as a basis for assessing whether a project works as intended, achieving its desired outcomes. Understanding performance data, such as productivity, profitability and energy use, in relation to how the building is used can provide valuable information for improving existing systems and for developing the design, procurement and operation of future projects. While key performance issues can be identified and resolved through POE and BPE, this process does tend to identify the areas of a project that have failed or are in the process of failing. Research has, for example, highlighted that thermal discomfort can tend to be associated with lower perceived workplace productivity and be a symptom of energy inefficiencies, badly configured control systems and poor management. Despite POE identifying problems, and even suggesting solutions, these negative insights can become a significant barrier to ensuring that appropriate reviews are implemented and, moreover, to the findings being made available to the team and other teams to learn from and develop. Fears of any liability or litigation will need to be overcome when identifying any areas that will ultimately increase the performance of a facility and, more significantly, the knowledge and competency of the profession to effect future solutions.

Methods of establishing POE and BPE There are a number of different methods of evaluating system performance and user satisfaction. Examples of these include:

The Soft Landings approach represents a significant review of the way the project team collects, analyses and uses operational and technical performance data from new-build and refurbishment projects. As a process it avoids many of the fears associated with highlighting poor areas of performance. For more information see the following publications from www.bsria.co.uk:

Access to use and performance data is invaluable for setting and achieving targets for future projects, and while some reliable information from existing studies is now available, Stages 0 and 7 recognise that a wider database and a cultural shift towards publishing these outputs will be required to ensure that information developed during this early stage benefits fully from the potential of Feedback. The project delivery is typically reviewed and defined within later stages of the Plan of Work. However, there may be specific processes and procedures, on the client’s side or otherwise, that have benefitted a previous project which can be used to inform and improve strategic outcomes at this stage. These lessons learnt can improve:

Understanding procedures and process performance will also inform decisions relating to the way information is produced and managed, either through a Building Information Modelling (BIM) approach or through 2D and 3D CAD processes.

How does CAD differ from BIM? The production of drawn information has progressed with the evolution of computer systems, from drawing boards and ink to a predominantly computer-aided design (CAD) approach, which, put simply, has digitalised the drawing process, allowing faster and more accurate provision of information. Drawing in pen or using CAD is still intrinsically the same process, using a vector-based approach to describe the design. Building Information Modelling, although more of a process, describes the design through the placement of objects, replicating the actual solution in a modelled format. These objects can also contain information relating to the cost, programme, specification, finish and maintenance requirements, allowing all the information relating to a project to be developed, accessed and maintained within a single source. Benchmarking employs actual metrics and measurable project-related research and data developed through precedent studies and the analysis of the outcomes from projects of a similar type and scale. The process measures and compares quantifiable variables, such as area, size of space, functional layout and cost/m2, against a number of different parameters, including:

Access to benchmarking data A number of professional bodies provide online access to benchmarking data, either openly or through a subscription service, providing quick and easy access to up-to-date best practice information. Other industry-related sites also provide measured data in relation to the parameters outlined above. These include:

Experienced clients may have completed projects from which they can offer benchmarked comparisons, and first-time clients might benefit from an understanding of how others have successfully achieved outcomes and aspirations, prior to determining their own brief. This type of analysis typically uses completed construction information to visually express successful areas for clients to review. This allows both a qualitative and comparative understanding of specific precedents and is a good opportunity for using the information to define aspirations, outcomes and requirements within the Strategic Brief. An extensive amount of data relating to specific parameters and functional requirements of building types is available on the internet. However, this information is often without context, incomplete and not validated. As highlighted above, some professional institutions and sector specialists record and validate data so that new projects can benefit from the benchmarked information, although both these forms of research should be substantiated using a number of alternative sources before being used to inform the Strategic Brief. In some instances, if locality is not an issue, it may be better to visit exemplary projects first hand and discuss with the owner/users how the building performs so that these insights can be reviewed and, if pertinent, captured within the brief. There are other embryonic forms of feedback associated with information modelling systems, such as those emerging from some of the GSL Early Adopter projects outlined on the BIM Task Group’s website (www.bimtaskgroup.org), where the opportunity for utilising a whole or a part of the digital model to form the brief for a similar project is being explored. These ‘digital briefs’ can comprise components that performed particularly well, or whole areas that demonstrate best practice in some spatial, functional or qualitative manner, that would be beneficial in the development of future designs. The HMYOI Cookham Wood Report (www.bimtaskgroup.org/reports) highlights the reuse of a prison cell, but this could also be a toilet pod, classroom, operating theatre or auditorium. Additionally, because of the way performance data and information are integrated within BIM objects, these digital briefs can not only highlight the spatial metrics, but can also include the environmental and construction performance, the specification and the final costs. This creates an element of certainty within the strategic requirements that may inform the budget and whole-life costing aspirations. Using modelled representations of successful performance and spaces as a brief will require a rigorous validation process in relation to context, use and the appropriateness and accuracy of any embedded information. With numerous BIM components, areas and spaces accessible online, care should be taken when assembling digital briefs to utilise only those from reliable sources, where the information has been independently checked against compliance and statutory issues, as a minimum. While the standardisation of a cell or a cell block can be understood in the context of outlining specific sector requirements within a digital brief, there is a danger that some briefs might begin to digitally assemble whole buildings as a representation of required outcomes, without the appropriate consideration of adjacencies, site and context, or the rigour of a process and a functional overview. Ultimately, a common sense approach will be required when compiling this information to ensure it is relevant and appropriate. Digital briefing will develop within sectors and building types to which it is particularly suited. If this approach is appropriately validated and utilised in context, the Strategic Brief might significantly change in the future, moving from a descriptive text-based document to an assembly of digital representations, performances and requirements defining the quality, outcomes and aspirations of the project. The Strategic Brief will form the basis of both the Initial Project Brief within Stage 1 and the Final Project Brief in Stage 2. In order to facilitate these future stages appropriately the Strategic Brief will, subject to the project requirements, endeavour to cover the principles outlined in the checklist below in order to define the client’s Core Objectives and outcomes.

The Strategic Brief – information checklist Typically, the Information developed within the Strategic Brief will include:

The information developed will document a broad understanding of:

The document may also:

The project responses to these issues will be determined by the size and scale of the scheme and the client’s requirements. It is important to consider carefully what areas are not needed at this stage to ensure that the Strategic Brief remains a simple, clear and concise document, delivering all the strategic information to progress the design. The Information Exchange required at the Strategic Definition stage comprises:

This document should be reviewed, approved and signed off at the end of the stage. In 2011, the UK government highlighted that it could significantly benefit from improvements in cost, value and carbon performance through the use of open, sharable asset information. It has subsequently produced a number of strategies to assist the implementation of BIM throughout the construction industry. These include:

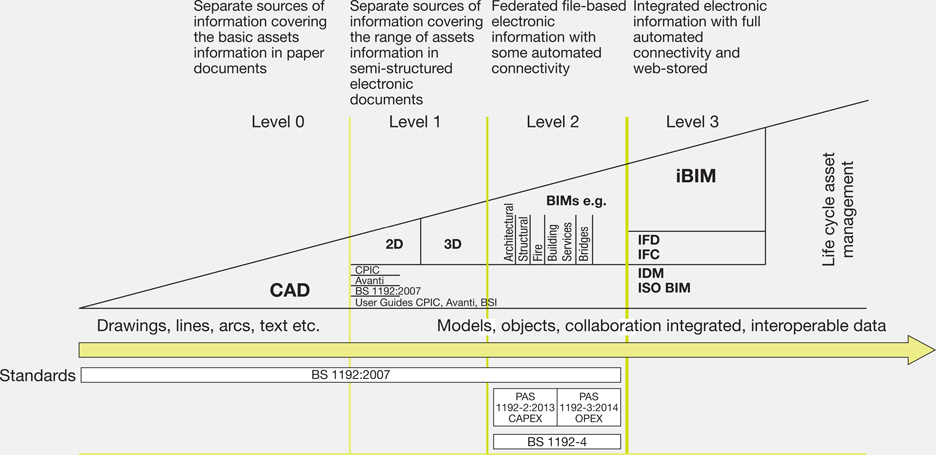

The UK government has also mandated that all publicly procured projects and assets will achieve the requirements of a Level 2 Building Information Model, as defined by the Bew-Richards BIM maturity diagram (figure 0.1). This will provide a ‘fully collaborative 3D BIM (with all project and asset information, documentation and data being electronic)’ (Government Construction Strategy, 2011). The mandate sets out a timeline to achieve this standard, as a minimum, by mid-2016. The BIM Task Group website (www.bimtaskgroup.org) provides a detailed overview of the strategies, systems and initiatives developed in support of this mandate, most of which are now in place to support a collaborative working environment.

What is BIM? BIM is an acronym that can be taken to represent either:

The use of these definitions remains fairly interchangeable and although consensus is beginning to settle on the model definition, its application is more accurately reflected when described as a wider process, such as building information management. The RIBA Plan of Work 2013 uses the acronym to mean ‘building information modelling’ (see page 229). However it is defined, BIM is more than just a modelling tool. It should be considered as a process that facilitates the delivery of a common output through collaboration and coordination. A BIM model is typically produced by a single discipline, eg the architectural model (AM) or the structural model (SM), and integrated with other design models to create a single representation of the project. This federated 3D model allows the full design to be accessed and viewed by the whole project team, including the client, users and stakeholders. PAS 1192-2:2013 refers to these models, federated or otherwise, as the Project Information Model (PIM), comprising graphical and non-graphical data and documents compiled throughout the design and construction stages. Once this information is verified as ‘as built’ the PIM is finally developed into the Asset Information Model (AIM) for assisting the operation and maintenance of the project during the In Use stage. A PIM is not drawn as with CAD systems, but rather assembled from a series of modelled components. These generic or very specific objects enable geometry and information to be coordinated and reviewed against other similar building elements and systems within the design. The objects can be developed to inform:

BIM represents a significant shift from traditional CAD methods, not only in the composition of the design, but also in both working methods and the transfer of information, with the whole project team sharing and utilising information within the context of the project model. This workflow can reduce the risk of coordination errors, and when additional clash detection software is used, issues within the developing design can easily be identified and resolved. Using a federated model to provide all Project Information digitally defines a Level 2 approach, as highlighted within the Bew-Richards level of maturity diagram. The plain language questions (PLQs) outlined by the BIM Task Group were created, using specific project examples, to set out the client’s minimum information requirements necessary to fulfil the Employer’s Information Requirements (EIRs) for each particular stage. The Digital Plan of Work (dPOW) highlights a number of Data Drops (specific information exchanges), which are defined by the model requirements and the resolution of each stage’s particular PLQs. All dPOW stages correspond to the RIBA Plan of Work 2013 stages, as highlighted in figure 0.2. There are no UK Government Information Exchanges (Data Drops) required at this stage. However, there are a number of PLQs, which require responses to define:

Although these questions are specific to government-procured projects, they can be used as a starting point to help outline the minimum requirements for information produced within this and subsequent stages in order to successfully progress the design.

Plain language questions The full list of standard PLQs used to develop EIRs in conjunction with the dPOW can be reviewed at www.thenbs.com/BIMTaskGroupLabs/questions.html

Standards and protocols The protocols and standards developed by the UK government underpin a ‘push’ and ‘pull’ strategy for adopting and developing Level 2 BIM processes within the construction industry. The dPOW and the unified classification system are the only two processes that have yet to be finalised in support of the overall BIM strategy. These are currently being developed within a BIM Toolkit produced by NBS, in conjunction with a number of other BIM-focused organisations. The BIM Toolkit will be freely accessible during 2015 and will help to ‘define, manage and validate responsibility for information development and delivery at each stage of the asset lifecycle’. In addition to supporting all the current key standards and guidelines, the outputs from the BIM Toolkit will also assist the development and production of the brief, Schedules of Services and the Design Responsibility Matrix. The Strategic Brief represents the beginning of a project’s development. While it is not uncommon for experienced clients to use their own in-house professional team to outline their Business Case and initial operational requirements, it is likely that most clients will be less sophisticated and will require the input of an architect or other design team member to help develop and articulate the required information. This assistance could also be provided by an independent consultant, such as an RIBA Client Advisor, who will provide impartial advice on critical issues and assist in developing the strategic appraisal and brief for the project.

RIBA Client Advisor An RIBA Client Advisor is typically an architect sitting on the client’s side of a project, independent of the ‘design team’, monitoring and helping to manage the process during its earliest stages. Putting you in control: The RIBA Client Design Advisor can be downloaded from:

www.architecture.com/Files/RIBAProfessionalServices/Directories/ClientDesignAdvisor.pdf

Depending on the nature of the project, the client in conjunction with the project manager and the lead designer/design adviser might also set out how the project team will be structured, what the scope of work for each team member might be and when they will be appointed.

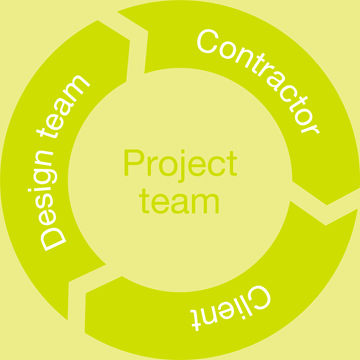

The project team Assembling a Collaborative Project Team (by Dale Sinclair, RIBA Publishing, 2013) suggests that those elements outlined in figure 0.3 will in many cases comprise the basis of the project team. In addition it highlights that cultural changes in the way the construction industry procures and delivers projects, better informed clients, the early involvement of the contractor and the expanding scope of the design team have resulted in a shifting dynamic that will need to be reviewed on a project-by-project basis in order to develop a coherent approach with the project team. Figure 0.3 The structure of the project team Some clients, in order to minimise design costs, may not want to appoint numerous consultants for the early design stages, prior to a planning permission being secured. The risks associated with this approach should be clearly outlined within the brief, so that any significant changes occurring as a result of delayed specialist or professional input can be addressed accordingly. Should the project implement a BIM approach at this stage, it is essential to involve the core design consultants early on, to assess and test the key constraints and outcomes, so that the Project Information is progressed using a collaborative approach.

Chapter 0 summary

Stage 0 is a new stage, during which project-specific needs are defined based on organisational requirements and on knowledge derived from the client’s ambitions and from successful projects of a similar type and scale. While the Strategic Brief is principally derived from these client-specific requirements, such as the Business Case and stakeholder input, Feedback is fundamental to understanding performance and outcomes from similar projects and how achievable aspirations and targets can be defined and delivered from the outset. Being able to identify theses core objectives succinctly at this stage enables a thorough appraisal to be developed and reviewed, ultimately determining whether the project progresses. The data and information produced and gathered from projects in operation is key to structuring the overall strategic response. Any improvements that can be identified by looking at how buildings have been produced and operate may result in significant changes to the way subsequent strategic aspirations are defined, with both the constructed and operational information becoming essential to the overall process. The Stage 0 Information Exchange is:

Additional information reviewed might include:

Introduction

What are the Core Objectives of this stage?

Developing a strategic approach

The Business Case

Exploring Project Outcomes and requirements

What are the Suggested Key Support Tasks and Project Strategies?

![]()

![]()

How can successful Project Outcomes be targeted?

![]()

How can the delivery process contribute to the Strategic Brief?

![]()

What information can constructed projects contribute?

![]()

How is Feedback evolving?

Documenting the Strategic Brief

![]()

General

Functional

Environmental

Statutory

Financial

What are the Information Exchanges at the end of Stage 0?

What are UK Government Information Exchanges?

![]()

Why is BIM different?

![]()

![]()

Who produces the Strategic Brief?

![]()

![]()