Process

“Our need for rules does not arise from the smallness of our intellects, but from the greatness of our task. Discipline is not necessary for things that are slow and safe: but discipline is necessary for things that are swift and dangerous”

—G.K. CHESTERTON

The Importance of Innovation Infrastructure

Effective process is the singular asset that differentiates a creative institution from an innovative one. Unequivocally, this is where the rubber meets the road. An operational commercialization or technology-transfer infrastructure is the foundation for building a high-innovation environment. It’s the absolute minimum investment an organization can make to play in the contemporary sphere of modern mission-driven innovation.

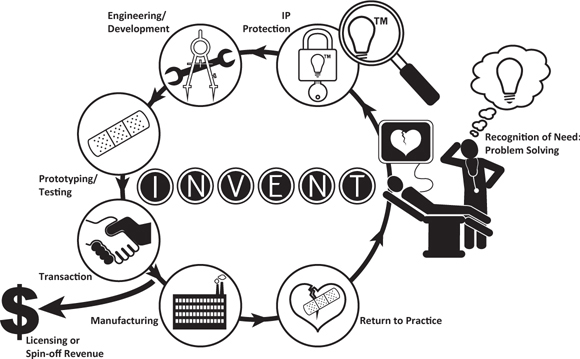

In the linear flow of product development that pervades most commercial markets, engineers try to predict market migration or “experts” use data from focus groups to predict consumer demand. The medical innovation journey, however, begins at the bedside or laboratory bench. An engaged caregiver recognizes an unmet need and draws upon his or her talents to address it. Then it’s incumbent upon the institutional innovation infrastructure to develop and divest the creative solution to return it to the clinician. This is the virtuous cycle.

Mastering the multi-step process by which technologies are gestated in this virtuous cycle revolving around the patient is both a challenge and an opportunity for newly emerging mission-driven innovation organizations. Details of how Cleveland Clinic Innovations (CCI) developed and operates its virtuous cycle—its commercialization infrastructure—are revealed in this chapter.

The success of such a model, and its major distinguishing characteristic from pure academic idea generation usually associated with research universities, is that the marketing is already done on the front end. Most of my colleagues have engaged in research and contributed robustly to discovery science, so we don’t diminish pursuit of “ideas for the sake of ideas,” but we’re sticking with our definition of innovation as meaning the process by which ideas are put to work.

The Virtuous Cycle: The Foundation of Mission-Driven Innovation

To participate in innovation today, an organization must invest in—or access through partnership—people and practices dedicated to operating healthcare innovation’s virtuous cycle. (See Figure 4.1.) A virtuous cycle, or circle, is the term used to describe a complex chain of related events or steps, involving strong expertise and engagement and compounding in a positive feedback loop. When operated optimally, it’s the opposite of the vicious circle, or cycle, a comparable set of recurring events that conspire to spin out of control and result in negative consequences.

We developed commercialization competencies and infrastructure early and robustly, and then grew them in a dynamic manner over the past two decades. While our earliest efforts were driven mainly by enthusiasm and old-fashioned trial and error, we quickly realized the necessity of approaching innovation with the same seriousness of purpose as establishing a new clinical program. We assembled the key players, mapped our needs, analyzed our capability, and designed a road map to become a leader.

We also developed disciplined processes so that inventors, investors, and market partners knew where they stood. A great deal of innovation administration relies on trust, which is the by-product of honest exchange, expectation setting, and delivery of the promised outcome or an honest explanation of failure. Only a disciplined engagement can yield such trust. Cleveland Clinic’s virtuous cycle evolved gradually, honed by repetition in handling thousands of new ideas.

Some of the more pertinent elements of our virtuous cycle include: (1) structured ideation engagements; (2) processes for handling of disclosure; (3) disciplined filters to identify viable and nonviable ideas; (4) development of metrics and monitoring milestones; and (5) engagement with advisors and deal makers. Key roles are also played by experienced legal, engineering, and regulatory professionals; these resources are integral to the operation of a world-class commercialization engine.

The virtuous cycle is easy to describe but challenging to erect and execute. Its success is first predicated on proximity to a wellspring of idea generation, the innovators that provide the raw material. At Cleveland Clinic, transformative concepts don’t emanate just from the physicians and research scientists, but from literally every corridor and echelon of the organization. This is why open access to the innovation apparatus is so critical. Cleveland Clinic’s advantage in stimulating widespread creative thinking is clear—an expert, often the world expert, recognized an unmet need and provided the makings of a solution.

The journey toward the marketplace, however, is a long one, during which the idea will take many forms. Within the virtuous cycle is a linear progression of those ideas toward commercialization, and the step that completes the cycle is when the innovation is returned to the inventor’s hands.

We coined an easily remembered acronym, INVENT, to cover the steps and events in the virtuous cycle. (See Figure 4.2.) Both seasoned and blossoming inventors have embraced the INVENT concept as a way to understand how successful ideas progress through the typical commercialization milestones.

FIGURE 4.2 Cleveland Clinic Innovations’ INVENT Commercialization Process

![]() Idea submission. An innovator completes our formal web-based Invention Disclosure Form (IDF), which describes the novel concept. The IDF (see Appendix A) is the basis for presentation of the idea to a clinical or administrative-specific Peer Review Committee (PRC).

Idea submission. An innovator completes our formal web-based Invention Disclosure Form (IDF), which describes the novel concept. The IDF (see Appendix A) is the basis for presentation of the idea to a clinical or administrative-specific Peer Review Committee (PRC).

![]() Need assessment. A PRC evaluates the clinical, scientific, and/or technical merit of the disclosure and considers and scores its ability to affect practice. High-scoring disclosures are passed on for evaluation of commercial potential.

Need assessment. A PRC evaluates the clinical, scientific, and/or technical merit of the disclosure and considers and scores its ability to affect practice. High-scoring disclosures are passed on for evaluation of commercial potential.

![]() Viability assessment. Endorsement from the PRC leads to attention from seasoned business leaders and staff advisors in the appropriate domain incubators. For Cleveland Clinic, these are medical devices, therapeutics and diagnostics, health information technology (HIT), and delivery solutions. A business case for the invention is prepared by domain experts, and an internal leadership group, the CCI Steering Committee, designs a path forward to the market for investors.

Viability assessment. Endorsement from the PRC leads to attention from seasoned business leaders and staff advisors in the appropriate domain incubators. For Cleveland Clinic, these are medical devices, therapeutics and diagnostics, health information technology (HIT), and delivery solutions. A business case for the invention is prepared by domain experts, and an internal leadership group, the CCI Steering Committee, designs a path forward to the market for investors.

![]() Enhancement. A development plan for the invention is prepared and executed. We reach out to the market to garner interest and gather relevant feedback. The commercialization strategy is refined by members of our Innovation Advisory Board (IAB), and inventions are marketed.

Enhancement. A development plan for the invention is prepared and executed. We reach out to the market to garner interest and gather relevant feedback. The commercialization strategy is refined by members of our Innovation Advisory Board (IAB), and inventions are marketed.

![]() Negotiation. Negotiations are initiated with interested corporate partners or investors. Decisions regarding the concept’s ultimate form, royalty-bearing license or spin-off company (NewCo), are made.

Negotiation. Negotiations are initiated with interested corporate partners or investors. Decisions regarding the concept’s ultimate form, royalty-bearing license or spin-off company (NewCo), are made.

![]() Translation. The original idea emerges on the commercial stage. Although operational responsibilities typically now fall to the licensee or NewCo operator, CCI usually maintains a governance role and monitors the licenses.

Translation. The original idea emerges on the commercial stage. Although operational responsibilities typically now fall to the licensee or NewCo operator, CCI usually maintains a governance role and monitors the licenses.

For more information on the INVENT Process, visit http://innovations.clevelandclinic.org/Inventor/Commercialization-Process.aspx#.VWM96VVVhBc.

The Virtuous Cycle Meets the Scholarly Circuit

Although we work with many for-profit companies that seek to understand and integrate medical innovation into their portfolios, we have long associated with sister organizations in the nonprofit sector—AMCs and research universities. An increasing number now embrace the so-called virtuous cycle of innovation that has been so advantageous for bringing life science and/or biotechnology advances to the marketplace.

Cleveland Clinic is chief among the pioneers and practitioners of the virtuous cycle. The answers to tomorrow’s medical challenges are identified by innovators engaged at the forefront of care and research, and developed in-house by those institutions that have built infrastructures to gestate ideas into commercialized outcomes. From the protection of intellectual property (IP) to the core engineering or coding activities and development of the investment/divestment relationships, these functions can now be handled by the same hospital or institution of higher learning from which the innovations originated.

The shift in innovation locus from industry to the AMC means a corresponding shift in the relationship between hospitals and corporations. We no longer simply engage in the sale of commercially engineered wares. Instead, the marketplace is increasingly coming to hospitals and academic institutions to obtain our product lines. A swelling portfolio of homegrown technologies is now developed at the same institutions at which they were discovered.

What makes it a cycle is that ultimately the idea takes the form of commercialized products (devices, drugs, or software solutions) that are returned to the hands of the inventors. The creators or their clinical colleagues employ the products at the patient’s bedside to improve and extend human life.

The Next Step in Evolution

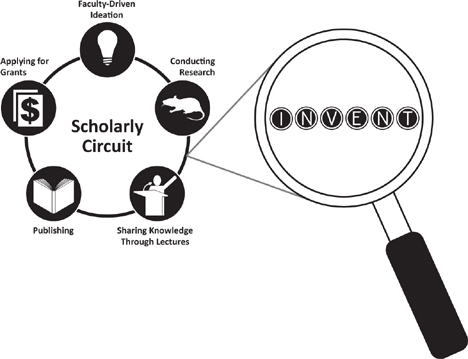

As a pioneer in commercialization, Cleveland Clinic has been active in discerning the next step in bringing ideas from the bedside and laboratory bench back to caregivers’ hands to help patients. It’s merging the innovation philosophies of AMCs and research universities to work better together on society’s healthcare challenges. Each party brings valuable components, and each can be equally rewarded.

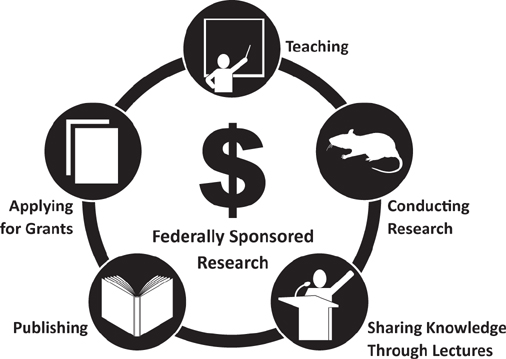

While universities typically pursue knowledge for the sake of expanding understanding, AMCs start with a problem and then bring to bear one or more expert minds to find the solution. The scholarly circuit moves on to share knowledge through presentations and publications. But according to the virtuous cycle within AMCs such as Cleveland Clinic, publication or public presentation is done after the IP has been secured, so that disseminated sharing doesn’t negate the ability to patent or otherwise protect our IP.

In the scholarly circuit, the holy grail of funding—from federal sources, special-interest funders, or philanthropists—starts another cycle. Regardless of the source, the goal is the funding itself, because it enables another trip around the circle, as depicted in Figure 4.3.

FIGURE 4.3 The Scholarly Circuit

A perfect storm of funding challenges is clouding the scholarly circuit. Let’s start with the biggie: federal funding for scholarly research is becoming scarcer, both decreasing and shifting away from basic and applied research toward some form of translational research. Additionally, healthcare reform has put pressure on hospital discretionary income, thus threatening research support. All of this is occurring at a time when industry’s investment in its own R&D is on the decline.

Can the more seasoned medical innovation process translate academic research into commercial outcomes? The result would be a win-win. The research accrues to the common good, and the funding gap is closed through revenue from commercialization.

What we suggest is akin to taking academic research to medical (innovation) school. Continue to celebrate discovery science, but amplify research with development approaches. Promote the liaison between the virtuous cycle and the scholarly circuit, while introducing industry as a trusted partner for funding and unmet need identification (Figure 4.4).

FIGURE 4.4 Uniting the Virtuous Cycle and the Scholarly Circuit

Tapping into the circuit at the appropriate time would align with mission-driven innovation in two ways: (1) by bringing the perspective of the healthcare-based innovation ecosystem to evaluate the developing technologies residing within research universities, more novel solutions to improve and extend human life could be recognized and pointed toward directly helping people; and (2) before patentability is precluded by public disclosure, the sophistication of the virtuous cycle could be employed to maximize commercial outcome, delivering additional sources to supplement grants to sustain the scholarly circuit.

The benefits are many and distributed. The medical innovation ecosystem would gain previously unavailable visibility into ideas evolving on university campuses that could cure diseases, and a new source of revenue could offset the decline in federally funded research dollars.

To summarize our key assertions about the university-based scholarly circuit and academic healthcare’s virtuous cycle:

![]() Healthcare innovation’s virtuous cycle has tended to realize more robust commercialization outcomes than the scholarly circuit.

Healthcare innovation’s virtuous cycle has tended to realize more robust commercialization outcomes than the scholarly circuit.

![]() Unprecedented funding pressures may be the catalyst for the two systems to find ways to work together productively to increase commercial outcome from research activity—research with development.

Unprecedented funding pressures may be the catalyst for the two systems to find ways to work together productively to increase commercial outcome from research activity—research with development.

![]() These models should be relatively facile to optimize by uniting them at a key stage of idea development—before ideas are publically shared in a manner that would negate patent protection.

These models should be relatively facile to optimize by uniting them at a key stage of idea development—before ideas are publically shared in a manner that would negate patent protection.

![]() Federal policy (the Bayh-Dole Act) is already in place to reward both members; alignment and execution of institutional policy could unite the virtuous cycle and the scholarly circuit for the benefit of both parties, their communities, and the patients they serve.

Federal policy (the Bayh-Dole Act) is already in place to reward both members; alignment and execution of institutional policy could unite the virtuous cycle and the scholarly circuit for the benefit of both parties, their communities, and the patients they serve.

Identifying, accepting, and addressing these realities is the first step in preparing the larger innovation ecosystem to withstand the pressures that will be applied to it in the new millennium. It paves the way for a convergence of the basic philosophies that allows ideas to become both intellectual and commercial successes. Ultimately, it doesn’t detract from, but adds to, the ability of the healthcare system to further its mission.

At its core, CCI is a service function. Our commercialization process provides professional amenities to inventors to develop and divest their IP. The lessons learned from managing assets as precious as a person’s ideas, especially ones that may save lives, are valuable. Dynamic effort should always be directed toward mastering each step, then aggregating the expertise into a reproducible practice, thus the virtuous cycle.

It is noble to transport an idea from the moment it sparked in the innovator’s mind back to his or her hands to eradicate suffering. The distinguishing characteristic that allowed CCI to pioneer the leading innovation function in healthcare was identifying and internalizing the key steps in the virtuous cycle. The operation and outcome of this function is completely aligned with our mission. The efficiencies and experience we placed within our walls has become another distinguishing characteristic of our enterprise and is as integral to our fabric as our dedication to patient care, scientific inquiry, and teaching.

An example of the level and impact of commercialization services that CCI provides is the recent new company ImageIQ. Most of the IP commercialized to date by CCI has been aimed at fulfilling Cleveland Clinic’s mission of providing better care of the sick. ImageIQ, a 2011 spin-off, addresses another mission pillar: investigation into their problems.

ImageIQ supports clinical research and drug and medical device trials with cutting-edge image analysis and software technology. Its advanced and powerful tools can combine, analyze, and objectively interpret anything from microscopic slides to visible light pictures. Whether it’s 2-D, 3-D, or 4-D, ImageIQ technology is capable of reducing what it sees to quantifiable scientific measurements.

Capabilities were developed and refined over a decade in Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute and Biomedical Imaging and Analysis Center. Realizing the technology’s commercialization promise, CCI provided initial funding from its Global Cardiovascular Innovation Center (GCIC) incubator—and everything from phone and Internet service to physical space and bouncing ideas off other smart people, which allowed the entrepreneurs to focus solely on the emerging business.

The company started with four employees but now has more than a dozen. It relies heavily on software experts and found the talent it needed locally, thanks to the area’s many universities and software businesses. ImageIQ’s initial markets were envisioned to be medical devices, pharmaceutical, and research organizations, but other sectors, including agricultural science, industrial manufacturing, and behavioral sciences, are showing excitement.

ImageIQ moved to a stand-alone building in 2014 and launched two new product lines in early 2015, an imaging-enabled electronic data capture and management system for drug and device clinical trials and a cloud-based preclinical image analysis website.

Step 1: Engage Innovators Through Education

To access innovators’ creative hard drives and software, we stewards of innovation not only must set the culture, we must ensure that we’ve cultivated awareness of what innovation is and how it works. We must build rapport and trust with the inventors to make them not only comfortable but eager to turn their ideas over to a function in which they have confidence.

The first stake you drive when you’re building your institution’s innovation platform is inventor outreach. Identify members of the innovator pool, get their attention, engage their ambition, and teach them the innovation protocols. We accomplished this through a structured program of Inventors Forums that cycle annually. Never meant to replace one-on-one connection between CCI and the inventor, these sessions are the boot camp where intellectual creatives become innovators and the ingenious become inventive. Some 250 to 300 participants typically attend.

Our forums are the “grand rounds” of innovation, ensuring that all the basics are covered and our colleagues are level set on information and expectation. The tricky part is also providing enough depth that veteran innovators get credits toward their innovation “doctorates.” At minimum, there’s enough change in patent law, venture investment trends, institutional IP policy, and regulatory standards that refreshers are always warranted.

We typically kick off in May, National Inventors Month. The sessions are 90 minutes long and mix didactic elements with case examples and generous question-and-answer segments. The faculty is composed of CCI staff, successful inventors from the institution, and outside luminaries who bring unique viewpoints. The sessions are videotaped and made available on Cleveland Clinic’s intranet for later viewing. The sidebar features examples of our annual Inventors Forum topics and session descriptions.

The goal of robust and recurring educational modules is to connect the individual’s creative DNA with the structured ideation and process orientation of the contemporary innovation practice. Many inventors simply want to turn over their IP to the CCI function, while others insist on step-by-step updates and want to know when even incremental progress is made at any of the germinal stages. The next section lifts up the hood so the reader can see inside the process at its most intimate detail.

Step 2: Importance of Filters

You might be surprised to learn the most frequent complaint from innovators about their institution’s commercialization apparatus. It’s not hearing that their “baby is ugly,” our euphemism that an idea is unoriginal, inadequate, or uninvestable. Instead, it’s ambiguity and delay regarding outcome. And nothing damages an innovator’s spirit more than being in a perpetual state of uncertainty.

Three variables typically contribute to ambiguity: delay in communication of the outcome; belief that the idea was evaluated by individuals of lesser expertise than the inventor; and lack of clear reasoning or methodology for rejection of the concept.

Just as you can’t blame inventors for illiteracy in the language of innovation, they also can’t be expected to comprehend the economics. We all inherently understand the concept of allocation of scarce resources, but when inventors believe they have the next cure for cancer, the dollars and cents just don’t seem overly relevant to them. This is precisely why an initial filter that yields a reliable predictor of success is one of the most valuable tools the innovation function can maintain.

To satisfy the three “anti-ambiguity” criteria we set forth, CCI constructed a best process that has become best practice, our Peer Review Committees. They evolved from an earlier mechanism to evaluate the clinical relevance and technical or scientific merit, the Commercialization Council, which operated from the earliest days of CCI. Let’s compare and contrast the two approaches to emphasize what we believe to be the contemporary standard for launching the initial stage of the virtuous cycle that occurs right after disclosure.

To be clear, our current process could never have evolved without the foundation laid by its predecessor; this is meant to be an illustrative example of our evolution and should encourage other organizations preparing to launch innovation capabilities to entertain beginning with a structure more resembling today’s approach.

Commercialization Council

For an academic healthcare system, the initial gate where technologies are evaluated for viability and promise can take one of two forms: “an inch deep and a mile wide” or the inverse. The Commercialization Council was populated by motivated and knowledgeable physicians, scientists, and engineers from key areas of specialization who were known to be frequent contributors to the invention disclosure flow. Representation was broad, not necessarily deep, with one individual from each of several selected specialties.

Typically meeting bimonthly to quarterly, this body evaluated ideas using a standardized disclosure form, itself an early and important development and the predecessor of our present IDF. (See Appendix A.) The outcomes were binary, a thumbs-up or thumbs-down based upon collective wisdom and democratic process.

Imagine a single research scientist sitting next to an obstetrician, an ophthalmologist, and other specialists, and CCI asking them to opine on a specific implant modification that increases the longevity of total hip replacements. Even if the single representative from orthopaedic surgery was present, it was hard to convince an inventor we had the expertise around the table to make the best decision about his or her technology.

This lack of deep expertise, coupled with a somewhat subjective approach to ultimately determining feasibility, made the Commercialization Council effective, but not as efficient as we now have become. The shortcoming was not missing the next blockbuster—the council did an amazing job of picking the big winners. The limitation was a relative weakness in separating the solid and sustainable from the frail and failing. Furthermore, without a sophisticated instrument to do a deep dive into the technology, it was challenging to plot a path forward or even to look back with certainty on how or why specific decisions were made.

Everything in life falls onto a bell-shaped curve, so it’s not surprising that the technologies that were one or two standard deviations from the mean in either direction got the appropriate attention and resources. The problem was that technologies under the middle of the curve tended to get too little attention to determine if they were champs or also-rans. The result was—you guessed it—delay and ambiguity.

Those twin curses were locked in a cause-and-effect relationship with the third inventor concern—lack of expertise of the evaluator. Again, this example is not meant to impugn the valued volunteers who populated our Commercialization Council, but to highlight the shortcomings of the initial filtering process. It is nearly impossible to expect even the most intelligent and engaged evaluator to know everything about each potential need or market.

Luckily, there were other forces at work that brought evolution to the PRCs: more interest and understanding of the innovation process and an increase in the number of disclosures from a more diversified field of inventors.

The Commercialization Council was pioneering and deserves respect—both the concept and the individuals who generously dedicated themselves to service. It was well suited for a nascent innovation function and provided the building blocks for CCI to become a worldwide leader in bringing ideas to the marketplace. Today, the stakes and inventor expectations are higher; the only constant is that resource allocation, including the time of experts to evaluate technology, remains challenging.

Peer Review Committees (PRCs)

You’ll recall my two basic models of distributed expertise—“an inch deep and a mile wide” and the inverse. Our two decades of commercialization success, the velocity of medical innovation and the pressing need to transform healthcare have spawned a third model: “a mile deep and a mile wide.”

Cleveland Clinic has the benefit of scale that germinated the concept of the PRC, with 3,200 physicians and scientists and more than 43,000 caregivers. We consider them all at the top of their game and potential innovators. Simultaneously, we have 400 to 500 invention disclosures per year from our campus alone. Both numbers increase when we include our Global Healthcare Innovations Alliance (GHIA) partners.1

With the anticipated quality and volume of disclosures generated in our environment, we required a strong mechanism to combat the trilogy of ambiguity. The answer was embodied in the PRCs.

After operating since the mid-1990s, the innovation and commercialization ecosystem at Cleveland Clinic had produced a large number of successful inventors, including those who enjoyed considerable financial return on their IP, either through a royalty-bearing license or equity in a spin-off company. Many were interested in giving back to the process that enriched them, as well as mentoring future generations of creators.

In addition, a fortuitous enterprise reorganization occurred in 2008. Cleveland Clinic is a vertically oriented, horizontally integrated multispecialty healthcare system. Our basic units of clinical care delivery departed from traditional academic departments and were reorganized around patient and pathology, becoming institutes. For example, orthopaedics and rheumatology were combined into the Orthopaedics & Rheumatology Institute. Neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry formed the Neurological Institute. The merits of this approach for the patients we serve are considerable. Aside from the convenience of physical colocation, the system or disease orientation promotes physician collaboration and efficiencies that translate into better care and patient experience.2

The direct benefit of the institute reorganization to the innovation process was that deep domain expertise was more easily solicited and accessed. We found that clinical and scientific leaders, many of whom had been successful innovators, were interested in deeper engagement in the commercialization process. We now had the logical assembly to evaluate technologies across the entire spectrum of care delivery with greater specificity and expertise.

Having multiple institute representatives populating the PRCs brought extraordinary breadth and depth of expertise to the front end of the evaluation process. For example, an orthopaedic disclosure is evaluated by five to eight fellow surgeons, usually all engaged inventors.

It became prestigious, in addition to fun and stimulating, to be involved in the PRCs. Institute leadership recognized the extra time demands, and we even saw a bump in the number of disclosures coming from PRC members.

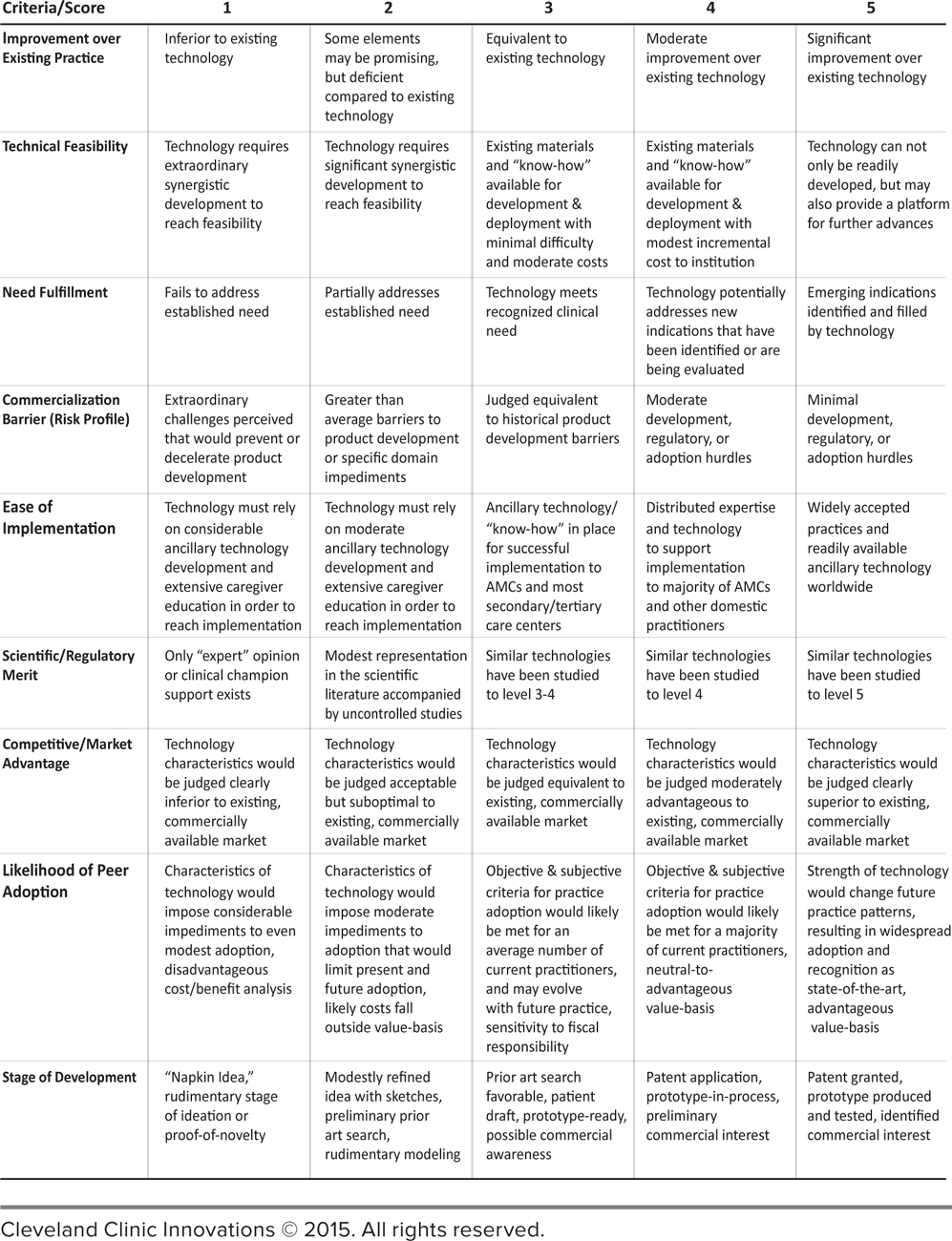

So the final requirement was to equip the PRCs with an instrument that allowed them to objectively describe their thoughts on the current status of disclosed ideas and the potential of new innovations to transform their specialties. This was accomplished by developing multivariable technology scoring platforms. (See Figure 4.5.) Nine essential criteria were divided into three levels and weighted according to their influence on both practice and prospective adoption. Experts could score a disclosed technology from 1 to 5, depending on alignment with clearly articulated criteria.

FIGURE 4.5 Cleveland Clinic Innovations Scorecard. This represents original Peer Review Committee scorecard matrices. This process is dynamic and ever-evolving.

The criteria are tough because the demands of investors and the marketplace are tough. The scorecard strips away wishful thinking from a proposal and helps to determine whether the idea is a superior one, can be built with existing technology, meets a demonstrable need, presents no extraordinary challenges, can be readily adopted by users, is based on verifiable principles, can compete for leadership in its space, and has a receptive target market.

The scorecard was a game changer because it directly addressed the exact concerns that our inventors were articulating all along. Now domain experts, usually inventors in their own right, were evaluating the intellectual contributions of their peers—just like refereed journals or grant applications.

One of the attractions of working at a great institution is the invisible power of culture that pervades every aspect of engagement. It comes back to that ubiquitous alignment with enterprise mission. We’ve never lacked for volunteers to populate and participate in our PRCs. The clinical and scientific leadership believe it is a duty and privilege to contribute to the innovation process in this fundamental manner.

With willing contributors and a steady flow of IP disclosures to assess, PRC meetings are held with regular frequency every four to six weeks. Inventors learn the fate of their technologies in a timely fashion and with objective evaluation criteria expressed across the multiple dimensions. While the inventor’s clock is ticking continually during the development cycle, the ticking is loudest and most anxiety-producing during the need assessment stage. When we became able to notify inventors within a specified time, their satisfaction skyrocketed.

Perhaps the most attractive component of the new PRC process was that inventors could react to an overall score as well as subcategory grades. This replaced the binary response that previously informed inventors only that their disclosure would either live or die, based upon a single show-of-hands vote. Even if the initial determination is that the technology needs improvement, there is an immediate and specific road map to enhance it. Precise deficiencies can be remedied more easily than vague objections.

Correspondingly, the scoring system has given CCI a mechanism by which we can validate our process and hone our capabilities. Initial scoring can now be corroborated by commercial success. We continually gain confidence regarding our adeptness at identifying winners and losers. This approach has improved our efficiency and resource deployment immeasurably.

We view the scoring system as a dynamic exercise. We are consistently evaluating the metrics that surround the process and its outcomes, and adjusting to take into account the market performance of the rated technologies. We believe that refreshing the methodology and membership of the PRCs will continue to be one of our key assets that differentiate our process.

Step 3: Determine the Innovation Destination: Commercialize, Monetize, Operationalize, Strategize

The role of an innovation unit in an organization’s success is not confined to technology-transfer activities. Innovation leaders would agree that transformation in their enterprises will not occur simply by securing a few more patents or a handful of additional licenses. The reason to maintain a robust innovation function is to make the entire organization more innovative. The presence and influence of an innovation crucible can set the culture and stimulate both creative thinking and disciplined practice toward bringing new solutions to reality—regardless of whether they “spin in” or “spin off.”

Innovation is a horizontal function, and it strengthens the fiber of most institutions that are, by nature, vertically organized into divisions, departments, or institutes. For this reason, innovation leaders must have an appreciation for both the overarching enterprise strategy and the aspirations of the individual organizational units. The way this plays out at Cleveland Clinic can best be understood by following the progression of new ideas through our process.

Once the PRC has opined, the nascent idea is considered an initially vetted and scored disclosure. Innovation functions must develop the antennae to determine whether an innovation has merit and to route the idea to its logical endpoint—or to say no or “not yet.” Granted, not every creative disclosed IP results in a spin-off company or a royalty-bearing license. But that doesn’t mean the remaining ones are not valuable, and we have emphasized a path for remediation and enhancement as a vital component of our process.

Although commercialization in the marketplace is the recognized outcome with which all are familiar, there are other ways to extract success and advance institutional goals with innovations that could deliver internal operational efficiencies or strategic advantage. The routing map for innovations emanating from a healthcare organization parallels that practiced in almost any business.

Ultimate decisions to spin off or spin in are complex; recognizing whether to direct innovations to the marketplace or retain them for strategic advantage is a critical skill that can be developed and measured. Admittedly, innovation on the campus of a healthcare system tends toward the model of disseminating scholarly research—we share our discoveries with the world. However, there are ideas that incrementally enhance processes or improve operational activities that may not have market traction but do create internal value.

To reiterate, the initial filter (CCI’s PRCs, for example) should inform the innovator and the institution whether the disclosure has what it takes to undergo the journey to ultimate commercial utility. When scientific and technical merit are verified and clinical feasibility is validated, then something of value has been identified. The question that follows is how the greatest value can be extracted. There is not just one type or method of handling for creative thought. The potential outcomes usually considered by CCI include commercialize, monetize, operationalize, and strategize.

Commercialize

The most readily recognizable and concrete innovation outcome is traditional commercialization. In general, this is reserved for protectable (patent-worthy) IP, most of which resides in the medical devices and therapeutics and diagnostics domains. Licensing IP to a larger organization, resulting in a royalty-bearing license, or creating a spin-off company are familiar ways to capitalize on transcendent thought in these specific areas.

We employ the term protectable IP to highlight the difference between ideas that are patentable and those that are not. There are different types of patents. Utility patents reflect the technological novelty and process by which the mechanical or chemical entity works. In the United States, design patents are available that cover the ornamental appearance of an article. Design registrations may be secured abroad. There are additional mechanisms by which IP can be protected, including copyright, trademark, trade secrets, and international options, such as CE marking, which abbreviates Conformité Européenne and indicates compliance with all legislative requirements for European Union sale. Experienced IP attorneys are the best resource for directing the innovator toward the proper choice.

Verifying that there’s no prior art, or evidence that the invention is not new, is often the first and fastest way to filter whether resources should be deployed for development. Innovators increasingly are performing their own preliminary patent searches on sources such as Google Patents. Most prolific creators have experienced the transient disappointment of learning that their “brand-new lightbulb” has been discovered by someone across the street or across the globe before they had the chance to announce it. The best do not wallow in defeat but go back to the drawing board.

If the professionals at CCI judge that the technology emerging favorably from our PRC process meets the criteria of novelty for a patent and would be served best by routing it to the commercial market through a license or company, then the next stop is one of our internal incubators. Modeled after the stand-alone incubator, which typically has more relevance after emerging companies are formed, our incubators are overseen by staff highly experienced in transactions with deep domain expertise.

Because of the large volume of disclosures and more mature IP that we manage, it’s simply not feasible to build an operational, financial, and governance structure around each one. Instead, multiple evolving concepts can be managed via a portfolio approach until they reach the critical mass to attract the talent and capital necessary to get to the marketplace.

Our incubator leads are impressive—in many ways, it’s harder to be the CEO of dozens of ideas than of a single company. Our leads continually bring their A game to please not a consolidated board of directors but individual inventors, themselves often acting as founders or CEOs.

Because these are homegrown technologies and processes, we don’t have a competition for entry or a prescribed time for the development stage. Instead, the incubator is the perfect stop for an innovation after it’s passed the technical filter and before market viability is determined by investment from outside entities.

Monetize

There is a difference between commercializing and monetizing. To commercialize involves the protection and transaction surrounding patented IP, while to monetize means to find new ways to leverage ideas and brand to create economic opportunity.

At Cleveland Clinic, we consider all of our colleagues to be experts, and there’s value in the level of mastery each caregiver develops in his or her sphere. Can this expertise be converted into a salable article that extends beyond the walls of our institution? Can caregivers’ know-how be defined, repackaged, and sold to others? The answer is often yes, and the intrinsic value is multiplied by brand identity and perceived level of achievement in the marketplace.

Cleveland Clinic is a $6.5 billion healthcare system. Forget for a minute that we exist to care for the sick, investigate their problems, and train future medical leaders. We manage large facilities, run a revenue cycle, direct a supply chain, operate parking facilities, serve thousands of meals, maintain a large fleet of vehicles, the list goes on. There is a great deal of expertise that accrues in the practice of these activities that can assist other hospital systems, as well as companies outside healthcare.

Caregivers engaged in these pursuits often see ways to improve incrementally how their jobs get done. Not infrequently, these caregivers also come up with disruptive advancements that may be industry-changing. This expression of innovation is just as valid as a new drug or device; these are transaction opportunities. In today’s healthcare landscape, when value basis is the driver, advancements that improve access, elevate quality, and control cost are vital.

Do they need to be registered, and can they be protected? We leave that to the attorneys to decide. Many of the developments fall under copyright, trademark, or trade secret. This is especially true in the field of software development, where copyright law is catching up to the pace of innovation. Regardless of whether these innovations can be protected by traditional marks, they still can potentially be transacted.

A supplementary way an organization may capitalize on expertise is through an advisory or consulting function. For decades, organizations have turned to the large consulting houses for strategic direction and tactical improvements, but in recent years we’ve increasingly seen peer-to-peer information sharing. Possibly galvanized by the external pressures we all feel in healthcare, and inspired by the new sharing economy, there has been a paradigm shift in the competitor-collaborator relationship model.

Once an organization has conducted a seemingly simple, but absolutely vital introspection to determine “what makes us us,” then core competencies can be codified and evaluated as teachable, scalable, or transferable. The plan to spin off the capability, and in what form, will eventually be a relevant discussion for the institutional and innovation leadership. So even if there’s not a patent plaque to hang on the wall, there may be a check from an innovative monetization in the mailbox.

Operationalize and Strategize

These two potential outcomes are fundamentally different from the two preceding ones. Commercialization and monetization are basically spin-off results of the innovation process. They are outward-facing engagements that translate the innovation identity of an innovator or organization to the marketplace. They’re designed to expand capability or brand awareness outside the walls of the organization in which they were gestated.

Two other innovation outcomes can be equally important, yet are not as readily identifiable. The difference resides in the predictors of their eventual success and influence on institutional practice.

The term operationalize describes the outcome for incremental process improvements that would be best developed and employed at the operational unit level. Ideas that may not have the qualities of protectable IP but could have substantive impact on patient care deserve to be treated as true innovations and also have the chance for their own impact trial. There are innumerable advancements that CCI never sees or that it immediately routes to the appropriate institute for further development and deployment. While plenty of these ideas undergo a similar litmus test to the one to which we subject marketable innovation, they are determined to be best developed and employed locally.

The strategize outcome is for innovations that may have institutional impact on competitive advantage. These are the “secret sauces” that create a margin of difference or distinguish a benefit in highly competitive markets. Institutional integration of innovation and strategic functions is required; innovation must not be marginalized from the overarching enterprise strategy, but instead interwoven with it. This is why so many individuals carry the dual title of “innovation and strategy officer”; these offices are physically and philosophically close.

What makes innovation-outcome decisions exciting yet challenging is the debate regarding whether to reveal and share versus integrate and operationalize. Would the idea garner more attention and potential revenue if commercialized? Or should the idea be developed within and then deployed to advance the enterprise? Obviously, such decisions are made case-by-case through discourse between the innovation hub and the C-suite.

It’s the responsibility of the innovation officers to be the champions of the creator contributing ideas to be operationalized or strategized. Whatever the method by which recognition and reward is distributed at your enterprise, you must credit those individuals who supply creative energy and content that may not fall to the bottom line. Fullest investment in innovation creates a generous platform that can accommodate creative expression of all types, regardless of whether it can be patented or banked.

Step 4: Employ Internal Incubation and Advisory Services

The incubator stage is the pressure test for market viability following the clinical and technical validation of the PRC process. Instead of a veteran business builder stewarding a single entity, our internal incubators take a portfolio approach. Because the stage, size, and level of complexity of these aspiring companies or concepts lend themselves to an aggregated management strategy by an expert, we’re able to advance multiple entities at a time. By leveraging shared services, internal and secured pools of proof-of-concept funds, and consistent contact with potential market acquirers, the incubator leader can successfully guide an ever-refreshing assembly of novel ideas.

Oversight provided by the incubator directors affords another unique advantage: they can detect complementary capabilities in two or more companies that may be fused into one in order to maximize success. This cross-pollination function could only be possible if one individual presides over the pool of emerging entities.

External advisory is also welcome at entry into the incubator and throughout the maturation of the progressing innovation. Early on, CCI recognized that the advice of experts in the investment and industrial sectors was vital for the success of mission-driven innovation. Inviting the marketplace in has been a key differentiator in our success. Establishing the Innovation Advisory Board has become a signature of our process and a model for others.

Unlike the PRC, the IAB provides the perspective of the marketplace, essentially presenting emerging technologies with the ultimate filter: will somebody buy or invest? Because the members are derived from the realms of venture capital, commercial innovation, institutional investment, corporate venture, and public policy, their viewpoints provide both immediate feedback and future direction for the most efficient and effective commercialization plans. Careful institutional policy analysis and development has created an environment in which direct investment by IAB members in the technologies they assess is permitted.

Interaction between the incubator directors and the IAB members is akin to a board of directors guiding the CEO of an early-stage company. Each interaction is a focused one that helps to determine the best plan for a technology’s journey to the market. The difference lies in that incubator directors are managing a larger portfolio of companies in their respective domains. For this reason, IAB members are drawn from our “big four” (medical devices, therapeutics and diagnostics, HIT, and delivery solutions), but their diversified knowledge gained by investing across the spectrum makes their advice relevant to almost all technology and service innovations, at whatever stage.

I want to recognize the vital contribution of current and past members of the IAB to the development and present status of CCI. Our success has largely been predicated on activating and connecting all members of the innovation ecosystem. To a significant extent, the IAB is the capstone to our structure.

Step 5: Execute Transactions

In addition to the collective expertise I have described, we have a deal team. We’re consistently negotiating with transaction pros from potential acquirers, so we must maintain competency.

Armed with fiduciary responsibility to optimally represent the inventor’s technology, as well as the expectations of our institution, we’ve honed this craft over many years. Spinning off more than 70 companies and managing about 600 royalty-bearing licenses has afforded us domain-specific and market-relevant insight.

The flippant dismissal that “doctors aren’t good at business” isn’t an acceptable reality when you’re charged with professionally managing the IP of your colleagues. We have approached business with medical ethics, but also with nothing less than a clear focus on achieving favorable outcomes for all parties involved in critical negotiations.

The backbone of our transactional arsenal is the finance committee of our Innovations Governance Advisory Board. Made up of our highest-level institutional officers, additional members of the office of the CFO, and selected members of the IAB, this ultimate connection with the enterprise ensures that we are making consistent and confident deals that align with our strategy and mission.

It’s Not a Sport Until You Keep Score

Innovation is a discipline with measurable results that reflects and stimulates a creative culture. One of the catalysts allowing CCI to excel in mission-driven innovation is measurement of outcomes. Dashboard indicators of the inventive potential and production of our caregivers are tracked and analyzed monthly, including patent activity, invention disclosures, transaction activity, and accounting.

Initially, it may be exciting to recount anecdotal expressions of creativity at your institution, but it’s not until you treat even the most innovative activity with objectivity that you join the modern practice of innovation. You must be able to plot your institution’s performance metrics and compare your capabilities to those of leaders in your industry and others.

It’s useful to monitor two broad sets of metrics: operational and outcome numbers. The former are barometers about how your process operates, and they illuminate pressure points that require attention if your institution’s innovation group is to function at highest effectiveness. The latter define your innovation identity in the marketplace through commercial success and its downstream impacts.

Operational Metrics

Mission-driven innovation is essentially the why of our work, and throughout this book are best practices regarding how we’ve built a successful innovation engine. Operational metrics described how well we’re doing our job.

Our innovation professionals are motivated to pursue constant improvement and innovate around their own processes to enhance output and satisfaction for inventors. They embrace that this as a dynamic process, and they must maintain flexibility. No two technologies are the same, as no two inventors are the same. We strive to have the fundamentals down, but we value being nimble enough to adjust on the fly.

The following are descriptions of some of the typical operational metrics we monitor and what they mean.

![]() Number of disclosures. The lifeblood of any innovation function is the flow of new ideas. The number of disclosures represents the turns “at bat” that an institution gets to develop meaningful IP. Maintaining an accessible yet detailed mechanism by which innovators can relate their novel concepts is critical, especially when it comes to patent protection. Our development of a web-based process for initial disclosure and tracking has been well received. To help increase the number of disclosures, we utilize all available internal communication channels to get the word out about our robust innovation entity. Our Inventors Forums bring creative minds together and disseminate information to a large group simultaneously.

Number of disclosures. The lifeblood of any innovation function is the flow of new ideas. The number of disclosures represents the turns “at bat” that an institution gets to develop meaningful IP. Maintaining an accessible yet detailed mechanism by which innovators can relate their novel concepts is critical, especially when it comes to patent protection. Our development of a web-based process for initial disclosure and tracking has been well received. To help increase the number of disclosures, we utilize all available internal communication channels to get the word out about our robust innovation entity. Our Inventors Forums bring creative minds together and disseminate information to a large group simultaneously.

![]() Number of returned/advanced disclosures. If the raw number of disclosures represents the “at bats,” then the disposition of these into the incubator stage, reflecting viable ideas from a clinical or technical standpoint, provides the numerator for calculating the “batting average.” When mature, an organization may experience an increase in both the number of disclosures and their quality, but in the beginning, the best way to improve batting average is to conduct a thorough analysis of the technology by domain experts at the outset.

Number of returned/advanced disclosures. If the raw number of disclosures represents the “at bats,” then the disposition of these into the incubator stage, reflecting viable ideas from a clinical or technical standpoint, provides the numerator for calculating the “batting average.” When mature, an organization may experience an increase in both the number of disclosures and their quality, but in the beginning, the best way to improve batting average is to conduct a thorough analysis of the technology by domain experts at the outset.

![]() Number of patent applications. Patents aren’t the only route to recognize intellectual accomplishment, but patents are the acknowledged vehicle for protecting IP. One decision that may face the sophisticated innovation leader is in what geographies to protect IP. For that discussion, it’s best to include the innovator who knows international practice patterns and a seasoned patent attorney with strong global experience.

Number of patent applications. Patents aren’t the only route to recognize intellectual accomplishment, but patents are the acknowledged vehicle for protecting IP. One decision that may face the sophisticated innovation leader is in what geographies to protect IP. For that discussion, it’s best to include the innovator who knows international practice patterns and a seasoned patent attorney with strong global experience.

![]() Amount of time between submission and decision. Keeping score shouldn’t simply be confined to volume or dollars. One of the most sensitive indicators of the performance of a commercialization engine is its timing in hitting milestones. This is especially true because inventors are appropriately impatient; they want to know the fate of their ideas, and this is true for the initial step and for subsequent steps as well. To enhance communication, as well as to hone our own processes, we’ve instituted electronic databases that track the progress of the disclosure through every step of our INVENT process. The inventor can monitor the progress, and just as important, the innovation managers can identify bottlenecks or underperforming assets.

Amount of time between submission and decision. Keeping score shouldn’t simply be confined to volume or dollars. One of the most sensitive indicators of the performance of a commercialization engine is its timing in hitting milestones. This is especially true because inventors are appropriately impatient; they want to know the fate of their ideas, and this is true for the initial step and for subsequent steps as well. To enhance communication, as well as to hone our own processes, we’ve instituted electronic databases that track the progress of the disclosure through every step of our INVENT process. The inventor can monitor the progress, and just as important, the innovation managers can identify bottlenecks or underperforming assets.

![]() Number of resubmitted disclosures. Most people don’t think of this one. However, if your evaluation process is fully developed, a remediation plan should accompany all but the IP nullified by prior art. This demonstrates the value of having multiple dimensions for evaluating technologies and ways to specifically describe the pluses and minuses of an inventor’s submission. If the process is executed correctly, the inventor will not only have the opportunity to resubmit an initially declined technology, but will have a road map regarding how to pursue improvement. Don’t just discard ideas that didn’t make the first cut; have a remediation function that follows a prescribed plan. We encourage the innovator to contemplate, refine, and resubmit the idea. You’d be surprised how some reflection and direction can resurrect an embryonic idea and ultimately get it over the finish line if the inventor is not discouraged but mentored.

Number of resubmitted disclosures. Most people don’t think of this one. However, if your evaluation process is fully developed, a remediation plan should accompany all but the IP nullified by prior art. This demonstrates the value of having multiple dimensions for evaluating technologies and ways to specifically describe the pluses and minuses of an inventor’s submission. If the process is executed correctly, the inventor will not only have the opportunity to resubmit an initially declined technology, but will have a road map regarding how to pursue improvement. Don’t just discard ideas that didn’t make the first cut; have a remediation function that follows a prescribed plan. We encourage the innovator to contemplate, refine, and resubmit the idea. You’d be surprised how some reflection and direction can resurrect an embryonic idea and ultimately get it over the finish line if the inventor is not discouraged but mentored.

![]() Inventor satisfaction. Dollars and cents are important, but the innovation function can never lose sight of the fact that it’s a service organization. Develop objective and subjective systems to ask inventors for feedback on how you’re doing. Open discourse about performance sharpens your capabilities and creates an even greater connection. Comfort and trust are critical lubricants to what can be an arduous process; these are best maintained by consistent communication and adherence to a service mentality. There is a fundamental difference between criticism and critical analysis; request the latter from your inventors, and use the information constructively when addressing your colleagues’ work.

Inventor satisfaction. Dollars and cents are important, but the innovation function can never lose sight of the fact that it’s a service organization. Develop objective and subjective systems to ask inventors for feedback on how you’re doing. Open discourse about performance sharpens your capabilities and creates an even greater connection. Comfort and trust are critical lubricants to what can be an arduous process; these are best maintained by consistent communication and adherence to a service mentality. There is a fundamental difference between criticism and critical analysis; request the latter from your inventors, and use the information constructively when addressing your colleagues’ work.

There are publicly reported numbers often used as benchmarks for institutional performance, such as those from the Association of University Technology Managers. I believe that engaging in comparison between institutions or in some form of ranking is largely unproductive. This may sound contrarian for one who espouses objectivity in analyzing the performance of his unit, but there’s not a lot of logic in scoring innovation production against the yardstick of another institution.

Innovation is not a competitive race between organizations. The factors that contribute to the number of disclosed or patented technologies or the number of spin-off companies can be fairly opaque. The value in recording metrics over time resides in determining the trajectory of your own group, year-on-year. If done with intellectual honesty and a dash of intuition, the answers that emerge from keeping an eye on trends can be invaluable.

An “innovation quotient,” or a level of IP flow, will eventually reveal itself as an innate characteristic. The reason why our practice may never come up with a true “IQ” is that the denominator is elusive. It’s exceedingly difficult to determine the divisor in the innovation equation—is it number of caregivers, size of technology transfer operation, research dollars, etc.? You get the idea. It’s possible to identify the number of patents or the size of the transaction, but nearly impossible to pick the right denominator.

This is why we usually tell organizations that the denominator is best considered your institution, until we can determine a better way to measure the variables. Your organization, assuming stability of size and dedication to a sustained business focus, will exhibit an inevitable leveling off in number of disclosures. It is then that you can determine how to rightsize your innovation apparatus and adjust the expectations of leadership around measurable outcomes.

Outcome Metrics

Sometimes we use the term outcome when we’re really speaking about income. That is partially true here, but tracking innovation success goes beyond the monetary measure. It’s frustrating that we can never really track the most important result of our ideas and the labors directed to bringing them into practice, the impact on the patient. As a substitute, we follow numbers that are relevant to our function.

![]() Number of granted patents. Many variables affect the ultimate procurement of a U.S. patent. It’s an achievement that turns an innovator into an inventor, and it should be a source of great pride and accomplishment. Innovation leaders should not only keep track of granted patents, they should celebrate them. We give the inventor a plaque with the first page of the patent emblazoned and recognize inventors at an inventors’ annual dinner. It’s a big deal to have a creative thought turn into a tangible advancement that will be forever memorialized. Celebrate it!

Number of granted patents. Many variables affect the ultimate procurement of a U.S. patent. It’s an achievement that turns an innovator into an inventor, and it should be a source of great pride and accomplishment. Innovation leaders should not only keep track of granted patents, they should celebrate them. We give the inventor a plaque with the first page of the patent emblazoned and recognize inventors at an inventors’ annual dinner. It’s a big deal to have a creative thought turn into a tangible advancement that will be forever memorialized. Celebrate it!

![]() Royalty-bearing licensing activity. Somewhere along the way, a decision becomes evident regarding the dispensation of a particular technology or suite of IP. Should it be licensed or spun off? A minority can stand alone and develop into a spin-off company, while a decided majority are attractive to larger operating entities to enhance their catalogs; such transactions are licenses. I’ve been disappointed that there is an outsize focus on spinning off companies, while royalty-bearing licenses are relegated to the backseat. We educate our inventors about the value of licensing technology and the recurring financial benefits they can receive. As seductive as it may sound to get the six- or seven-figure payday that may be associated with a company acquisition based on your technology, the veritable “home run,” hitting a bunch of singles and doubles isn’t a bad strategy. Our experience is that education, expectation setting, and common sense are valuable tools when discussing dispensation of technology with all institutional stakeholders. Don’t try to force every development into a mold for which it may not be best suited.

Royalty-bearing licensing activity. Somewhere along the way, a decision becomes evident regarding the dispensation of a particular technology or suite of IP. Should it be licensed or spun off? A minority can stand alone and develop into a spin-off company, while a decided majority are attractive to larger operating entities to enhance their catalogs; such transactions are licenses. I’ve been disappointed that there is an outsize focus on spinning off companies, while royalty-bearing licenses are relegated to the backseat. We educate our inventors about the value of licensing technology and the recurring financial benefits they can receive. As seductive as it may sound to get the six- or seven-figure payday that may be associated with a company acquisition based on your technology, the veritable “home run,” hitting a bunch of singles and doubles isn’t a bad strategy. Our experience is that education, expectation setting, and common sense are valuable tools when discussing dispensation of technology with all institutional stakeholders. Don’t try to force every development into a mold for which it may not be best suited.

![]() Number and valuation of spin-off companies. I’ve already lamented that our innovations community has become entranced by quantity over quality when it comes to spin-off companies. Hanging another logo in your reception area can be a badge of honor in the game of moving a large number of ideas down the path of commercialization. But there are two cautions to avoid: (1) overly incentivizing your innovation leaders to produce spin-offs, and (2) demoting the opportunity for a lucrative license and holding out too long because a spin-off is “sexier.” Go in with an open mind, and let the educated discussion of stakeholders and the market dictate the right choice.

Number and valuation of spin-off companies. I’ve already lamented that our innovations community has become entranced by quantity over quality when it comes to spin-off companies. Hanging another logo in your reception area can be a badge of honor in the game of moving a large number of ideas down the path of commercialization. But there are two cautions to avoid: (1) overly incentivizing your innovation leaders to produce spin-offs, and (2) demoting the opportunity for a lucrative license and holding out too long because a spin-off is “sexier.” Go in with an open mind, and let the educated discussion of stakeholders and the market dictate the right choice.

This scorecard of operational and outcome metrics forms a solid basis for launching or refreshing an institutional innovation function. Tracking these parameters lets you know your game. Innovation is not a pursuit in which benchmarking is either logical or healthy; perhaps you can pressure a physician to see three more patients per clinic to increase her numbers, but you can’t extract more innovation from a creative mind by waving benchmark data in the face of an inventor. Likewise, if the hospital system across town or the university across the country has more patents or licensing revenue than yours, it didn’t use up the “creative karma” in the universe and leave you inadequately resourced to come up with the next idea. It’s not a zero-sum game.

Work on optimizing your own innovation process, and the results will follow—some dollars, some handshakes, and many patient lives improved or extended.

It’s Not the Big That Eat the Small—It’s the Fast That Eat the Slow

A final variable remains: the elusive and ubiquitous influence that Father Time has on everything we do in innovation.

When the prize is a first-to-market or first-mover advantage, then speed matters. The challenges to innovation, especially in academic settings, can range from institutional inertia and lack of infrastructure to the arduous patent process and regulatory hurdles. Acceleration in innovation is not achieved by cutting corners, but by learning efficiencies, economy of action, and the power of simultaneous versus sequential action. Identifying choke points and developing strategies to alleviate them is the purview of the chief innovation officer.

Another way time impacts the innovation process concerns the decisions regarding when and how to pull the plug on a technology. Innovation leaders often speak of the Three Fs of successful innovation: fast, frugal failure. The innovation champion must learn how to filter the promising solutions from the inferior ones. It’s always tough to sundown a project, but the anguish is multiplied when you’ve nurtured and resourced it, or worse yet, practiced alongside its originator.

At CCI, we’ve equipped ourselves with the right tools so we won’t be the limiting factor. We’ve also identified appropriate milestones and processes common to the development of most technologies in key domains.

Some ideas die natural deaths, while others linger before the determination that they were ahead of their time or market demand, didn’t have ultimate customer appeal, or would consume too many resources or too much effort per unit. I’d simply remind innovation leaders to keep an eye on the clock, while also looking at the dashboards constructed from the elements discussed previously. There’s a reason why some projects take longer, but when the calendar drags out of proportion to your experience and the market cycle, the initiative itself may be begging to be put out of its misery.

The most successful organizations are intrinsically agile—nimble in delivery by seizing advantage of opportunity windows. This means having sufficient resources to direct to the “next big thing” when necessary. If your resources are deployed in life support for failing concepts, you’ll never realize the benefits of speed.

The business of innovation has been portrayed alternatively as a marathon or a sprint. Nowadays, it feels like a marathon at sprinter’s pace. Unpromising projects shackling your ankles will prevent you from reaching the finish line in a timely manner to satisfy inventors or conserve your resources. The answer is to build time sensitivity into all of your processes and honor it just as much as dollars, patents, and spin-off companies.