Practices

Are You Ready to Lead Innovation?

Just like a purposeful device or an elegant molecule, the practice of innovation has a structure and function that determine its level of success. This chapter will detail how diverse types of innovation, contributing a variety of solutions, move through an institution’s innovation infrastructure. We’ll also cover the basic proprietary tools that Cleveland Clinic Innovations (CCI) has developed to assess the value of individual technology disclosures and the preparedness of entire institutions to participate in structured innovation.

At its core, successful innovation is about execution. While CCI’s success is due to identifying promising technologies, it is equally derived from appropriately saying no and shutting down projects to suitably direct time and resources.

While exercising discipline in the handling of disclosed technologies may be paramount, almost as critical is developing an understanding of the various mechanisms by which mission-driven innovation is derived. Experience and insight is required to recognize and gestate ideas emanating from the different routes by which innovation is fostered. Expertise in both the intake and development processes maximizes the chances of success. Ultimately, this level of mastery allows the institutional innovation practice to be sustainable and scalable.

The Six Degrees of Innovation

In CCI’s nearly two decades of experience, we’ve identified six distinct varieties of innovation. In cataloging them, I’ve been inspired by Peter Drucker, who has contributed many concepts germane to our understanding of innovation and entrepreneurship.

There’s elegance in the simplicity by which he communicates the seven sources of innovation in his landmark book, Innovation and Entrepreneurship: Practice and Principles.1 This fundamental work inspired us to think more deeply about the varieties of mission-driven innovation, and we came up with a slightly different, yet intersecting approach called six degrees of innovation.2 We chose the term degrees to reflect the degrees of a compass. A compass is a fitting metaphor, as a sense of direction, along with organizational nimbleness, to adjust to changing conditions is crucial to the accomplished innovator. Additionally, a compass is an instrument that tracks where you have been and beckons you to unexplored territory on the journey—in this case, to cover the entire innovation landscape.

First-Degree Innovation: Opportunistic

F. Mason Sones, Jr., after whom the annual award recognizing Cleveland Clinic’s top innovator is named, was regarded personally as a curmudgeon, professionally as a genius. Though his seminal discovery of coronary angiography was made in 1958, his name is still invoked with just deference for the innovation’s huge impact on modern medicine—and on the reputation of Cleveland Clinic as the world leader in heart care. Dr. Sones’s discovery illustrates opportunistic innovation because his work exemplifies the intersection of serendipity and the prepared mind.

The aorta is the major vessel carrying blood away from the beating heart to nourish the rest of the body. Just after blood is ejected from the left heart chamber (the ventricle), smaller conduits, the coronary arteries, carry blood to the heart itself to keep the dynamic muscle alive.

Prior to 1958, direct imaging of the coronary arteries had not been attempted. In fact, it was believed that direct dye injection into these small arteries would cause sudden death. The Nobel laureate in 1956 for discoveries concerning heart catheterization, André F. Cournand, declared in 1950 that no physician should ever perform such a procedure.

Dr. Sones was a cardiac and aortic imaging expert. In October 1958, in his Cleveland Clinic basement laboratory, Sones was supervising trainee Royston C. Lewis in the study of a 26-year-old patient with rheumatic fever, a common malady of the time resulting from untreated streptococcal infections. Performing the angiography procedure was a two-person job: one physician threaded the tube into position in the circulatory system and prepared to inject the radiopaque dye that filled and defined the vessels, while the second manned the imaging screen sunk beneath the exam table in a pit. Neither physician could see what the other was doing.

That day, Dr. Sones was viewing the beating heart and great vessels through a periscope, while Dr. Lewis was positioning the hollow tube to deliver 50 cc of dye into the heart chambers and aorta, or so he intended. Instead, the catheter moved just a millimeter or two, which caused the dye to be delivered not into the capacious ventricle, but directly into the small-caliber coronary artery system. The bolus of dye injected into such a small vessel stopped the patient’s heart, but not before Dr. Sones witnessed the first elucidation of the coronary artery system by direct cannulation.

A happy ending was ensured when Dr. Sones restarted the patient’s heart within seconds. A new era in heart and vascular diagnostics was begun, with this discovery leading to greater understanding of coronary anatomy, physiology, and pathology.

Dr. Sones subsequently collaborated with René G. Favaloro, a young Argentinian cardiovascular surgeon visiting Cleveland Clinic to hone his craft, to perform the first coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). Prior to CABG, patients who suffered a heart attack were treated symptomatically with rest and pain medication, and the morbidity and mortality rates were unacceptably high. Although the frequency of CABG has decreased by nearly 50 percent in the past decade due to less-invasive alternatives, it still accounts for almost 2 percent of all annual U.S. operations, a number exceeding 200,000.3

In a letter some three decades later to fellow world-renowned cardiologist J. Willis Hurst, Dr. Sones reflected on the aftermath of the inaugural incident: “During the ensuing days, I began to think that this accident might point the way for the development of a technique which was exactly what we had been seeking.” An accident? This is a prime illustration of opportunistic innovation.

The Mason Sones example contains the two key elements essential for opportunistic innovation: a fertile environment and an opportune event. Opportunistic innovation is different from a so-called innovation “lightning strike,” because in that situation, prevailing randomness may not permit the germinal action to be witnessed or experienced by the appropriate agent.

A common lament when describing a medical diagnostic challenge is that the key piece of data “may have seen me, but I did not see it.” Some barrier prevents the eureka moment from occurring. Maybe it’s a knowledge gap. Perhaps the glimpse is experienced out of context or at a time of distraction or fatigue. Or maybe there’s just too much noise surrounding the would-be innovator because he or she is buried beneath the mundane or irrelevant.

Here’s the implication for mission-driven innovation champions and the institutional functions they lead regarding opportunistic innovation: it’s your responsibility to optimize the setting around your creatives and inform them of the benefits of perpetual preparedness to discover.

Expertise is ubiquitous around us; you must trust that each of your colleagues is as knowledgeable in their craft as you are. They know the unmet needs and where pressure points exist and very likely are presented with novel solutions. Make sure your associates are engaged thinkers who know how to recognize solutions that will make a difference. In addition, ensure that your would-be innovators are comfortable about engaging in your process and that it’s easy to do so. The moment may be fleeting when the right problem and the right innovator intersect; being equipped to receive the novel solution and run with it is the purview of the effective innovation function.

Recommendations to inspire and capture opportunistic innovation include:

![]() Continually remind your colleagues that everyone is an expert and an innovator. Keep innovation top of mind and foster connectivity by holding specific events throughout the year and by creating a site for information exchange on your institution’s intranet.

Continually remind your colleagues that everyone is an expert and an innovator. Keep innovation top of mind and foster connectivity by holding specific events throughout the year and by creating a site for information exchange on your institution’s intranet.

![]() Educate your organization about the powerful, yet ephemeral nature of creative thought. Encourage colleagues to record their aha moments. Provide simple tools to promote this activity, such as small notebooks. Have paper napkins at meal functions that carry the message and the metaphor; encourage attendees to flip the napkins over and note their burgeoning ideas.

Educate your organization about the powerful, yet ephemeral nature of creative thought. Encourage colleagues to record their aha moments. Provide simple tools to promote this activity, such as small notebooks. Have paper napkins at meal functions that carry the message and the metaphor; encourage attendees to flip the napkins over and note their burgeoning ideas.

![]() Ensure that your idea development process is easy to access and nonthreatening to the inventor. We don’t advocate a one-size-fits-all or black-box approach for opportunistic innovation.

Ensure that your idea development process is easy to access and nonthreatening to the inventor. We don’t advocate a one-size-fits-all or black-box approach for opportunistic innovation.

Second-Degree Innovation: Organic

One of the reasons I have the best job in all of healthcare is that I work at a physician-led institution where the CEO is one of the world’s foremost proponents of medical innovation. Toby Cosgrove is not only a highly respected medical executive, he’s a fellow surgeon and prolific inventor holding more than 30 patents. Before taking the helm of Cleveland Clinic, Dr. Cosgrove performed some 22,000 cardiac surgeries, and he has authored nearly 450 scholarly articles and book chapters. Treating disorders of the heart’s mitral valve is among his fortes. Dr. Cosgrove is an example of an organic innovator.

The importance of the mitral valve cannot be underestimated. Blood is collected in the upper chamber of the heart, the right atrium, after delivering its precious cargo, oxygen, to tissues all over the body. Before the right ventricle propels blood to the lungs to reload oxygen for another round, the blood transits through the mitral valve. If damaged by disease or disorder, the valve can become floppy, rendering it inefficient in its work guarding the aperture between the two chambers. The results can be benign, such as a heart murmur, a nuisance to be explained each time you get a physical, or it can be life-threatening.

A structure as delicate as the mitral valve is challenging to reconstruct. Even the skilled surgeon encounters difficulty in achieving the right balance between flexibility and tautness—and remember, the heart is beating during this technical exercise!

Drawing on a design reminiscent of his wife’s embroidery hoop, Dr. Cosgrove figured out that by employing a cloth-covered, semicircular spring device called an annuloplasty ring, the mitral valve could be repaired predictably with lower complication rates. This device put capability in the hands of many surgeons and improved the lives of thousands. It represents organic innovation at its finest.

Organic innovation arises when experts, in the course of their frontline experiences, recognize ways to advance their craft. It’s the workhorse of all mission-driven innovation. In many ways, it’s the most important and fundamental form of reducing transcendent thought to practice. It’s often the most hard-won, but also the stickiest and most sustainable. Organic innovation is the most common type of creative thought generation and the one around which every innovation function or technology transfer office must build its infrastructure.

At Cleveland Clinic, every specialty is replete with one or more colleagues considered among the world’s experts, and each vertical care delivery unit (we call them institutes) maintains a deep bench. The collaboration with fellow experts that is so catalytic to innovation is a distinctive strength of the Cleveland Clinic community. It’s a great place to practice and innovate because none of us perceive we’re alone in being at the top of our game, and there is never a barrier to seeking the opinion of another maven practicing alongside us.

Two issues require clarification and differentiation from opportunistic innovation. First, just because organic innovation is the blocking and tackling of innovation does not automatically imply that organic innovation is incremental. In fact, organic innovation can be disruptive.

Second, the distinction between opportunistic and organic innovation is that the former is a spark, the proverbial lit match that lands in the gasoline shed. The latter is the smoldering ember that finally reaches the right temperature and conditions to ignite evident and actionable breakthrough. Both opportunistic and organic innovation can feature the same elements, human and otherwise. But the essential catalyst for the opportunistic innovator is attentiveness to the unexpected, while the organic innovator mines ideas over time through ceaseless exposure.

It shouldn’t be surprising that opportunistic and organic innovation track together. The most experienced people are often the most prepared to recognize and accept the unique stimulus.

Recommendations to inspire and capture organic innovation include:

![]() Cultivate frequent contact with your most experienced personnel and prolific innovators. From casual lunches to recurring meetings, hearing what the experts see, think, hear, and say is valuable to an innovation team.

Cultivate frequent contact with your most experienced personnel and prolific innovators. From casual lunches to recurring meetings, hearing what the experts see, think, hear, and say is valuable to an innovation team.

![]() Maintain the crucial processes that propel innovation through the virtuous cycle.

Maintain the crucial processes that propel innovation through the virtuous cycle.

![]() Be a proponent for innovation in its most basic form, both inside and outside of your institution or organization.

Be a proponent for innovation in its most basic form, both inside and outside of your institution or organization.

Third-Degree Innovation: Synthetic

Synthetic innovation reflects the belief that innovation occurs best at the intersection of domains. Whether the commodity is knowledge, experience, resources, relationships, or even culture, uniting creative people and institutions is one of the most catalytic ways to advance innovation. Furthermore, allowing creatives to bring their life experiences into medical innovation can also pay dividends.

Innovation can come from a doctor-patient interaction at the bedside, a research inspiration at the laboratory bench, or seemingly out of thin air. When Anesthesia Institute chair David L. Brown, a general aviation and former military pilot, was making a cross-country flight, the advanced avionics controlling his plane inspired him to conceive a novel system to help manage patients’ anesthesia needs during surgery.

Much like a pilot, an anesthesiologist relies on numerous complex factors to keep patients safe while in the medically induced state that allows surgery to be performed painlessly and without recollection. Anesthesiologists, however, didn’t have computers or control towers to help guide clinicians to the correct decisions. In addition, complex surgeries can take many hours, and as is the case with all humans, clinicians are subject to fatigue and distraction.

Computers don’t have these stresses and are great vigilance monitors. Dr. Brown invented Decision Support Systems (DSS), which amplified physician judgment and increased capacity to manage multiple patients. DSS is like a tap on the shoulder to keep clinicians ahead of the case, providing anesthesia staff with an extra set of eyes and extensive cognitive processing power both to improve clinical and management decision making in the perioperative environment and to allow anesthesiologists to react more rapidly to potentially harmful trends.

DSS was commercialized and further developed by CCI’s ninth spin-off health information technology (HIT) company, Talis Clinical, LLC. The DSS platform has been combined with additional HIT tools to help manage patients in other acute care settings. The volume of hospitals, clinicians, and patients this technology benefits is remarkable.

Dr. Brown’s contribution exemplifies one form of synthetic innovation, in which the inventor removes partitions in his brain to allow mingling of experiences and expertise. When inventors feel that freedom to ideate, the job of the innovation leader is to remove roadblocks.

Cleveland Clinic’s most tangible expression of synthetic innovation at work on an institutional scale has been the Global Healthcare Innovations Alliance (GHIA), the largest consortium of academic medical centers (AMCs), research universities, and aligned corporate partners dedicated to mission-driven innovation. The alliance has paid dividends in co-invention and sharing of innovation culture.

Recommendations to inspire and capture synthetic innovation include:

![]() Cross-pollinate within your own organization, across the street, across the country, or around the globe.

Cross-pollinate within your own organization, across the street, across the country, or around the globe.

![]() Be proactive about defining the rules by which partnerships will be executed, including joint management agreements and definitions on how ownership and distributions will be executed.

Be proactive about defining the rules by which partnerships will be executed, including joint management agreements and definitions on how ownership and distributions will be executed.

![]() Consider relationships with organizations that don’t look like you. Whether bringing together urban and rural hospitals or combining healthcare entities with industrial giants, concentrate less on what each party does and more on how and why they do it. When you ensure cultural alignment first, complementary and supplementary facets are much easier to identify.

Consider relationships with organizations that don’t look like you. Whether bringing together urban and rural hospitals or combining healthcare entities with industrial giants, concentrate less on what each party does and more on how and why they do it. When you ensure cultural alignment first, complementary and supplementary facets are much easier to identify.

![]() Don’t try to advantage yourself or your institution against a potential or secured partner. It will either be obvious from the outset and derail the relationship or will besmirch your reputation when discovered and forever going forward.

Don’t try to advantage yourself or your institution against a potential or secured partner. It will either be obvious from the outset and derail the relationship or will besmirch your reputation when discovered and forever going forward.

Fourth-Degree Innovation: Geographic

A compelling example of geographic innovation is the partnership CCI developed with Parker Hannifin Corp. For those unfamiliar with Parker, chances are the company’s products have touched you, or vice versa, multiple times today, especially if you drove in a car, flew in a plane, or operated a machine. Parker is a Cleveland-based motion-control giant that solves some of the world’s most challenging engineering problems.

When we sat down to explore whether there was commonality on which to build a sustainable relationship, there was an initial polite but palpable level of incredulity in the room. To paraphrase Parker executives, “I’m not sure that you would be interested in what we do. We solve problems such as getting fluids to flow through tubes with valves in them.” CCI responded, “That’s exactly what our cardiologists and urologists do.” Since those initial meetings, we’ve built a robust medical device portfolio with Parker and a valuable intellectual property (IP) estate through co-innovation.

I’ve had many of my best ideas in orthopaedic device development walking through the hardware store. Translocating an idea—even existing technology—for use in an entirely different discipline is also an expression of geographic innovation.

Another expression of geographic innovation is attracting successful innovators who have never resided in our sphere into medical innovation to leverage their talents to help patients. That’s what we did with our hugely successful spin-off company, Explorys, which was recently purchased by IBM’s Watson Group.

Big data is big news these days, and Explorys is one of the leaders in harnessing a powerful, secure software platform to provide near-instantaneous answers that ultimately lead to better treatment, enhanced access, and lower cost. Explorys can examine its 315 billion data points from a population health perspective or do a deep dive into a single patient’s medical record. There is amazing potential for clinical care delivery and research.

One would think that cofounders Stephen McHale and Charlie Lougheed spent decades in and around hospitals to garner the depth of understanding required to bring such a powerful tool to healthcare, but not so. These computer geniuses came from the worlds of banking, defense, and telecom, where facility with big data has thrived for years. Their association with cofounder and Cleveland Clinic physician Anil Jain and CCI “took them to medical school.” The result was a unique archival and analytic tool that logically fits in healthcare but might have been sequestered outside of the sector if not for geographic innovation.

Explorys was acquired by IBM’s amazing Watson Healthcare team in early 2015 after CCI spun off the company in 2009. At the time of the IBM acquisition, Explorys neared 150 employees and had curated anonymized records on more than 50 million patients in databases that can be mined to gain insight on activities ranging from medical research to care delivery.

Healthcare is trending up toward 20 percent of the U.S. gross domestic product. If a company isn’t already in healthcare, it’s trying to get in, or at least considering it. The most successful mission-driven innovation organizations in healthcare will be portals of bilateral information flow that enhances the creative potential of both the medical sector and nontraditional partners from outside healthcare. This will include adapting existing consumer technology to medical applications and vice versa, or promoting collaboration. In either case, visionary institutions will act as the stewards that translocate people, technology, or both between adjacent or even remote sectors.

Recommendations to inspire and capture geographic innovation include:

![]() Keep your eyes open. Just as a great athlete in one sport can appreciate the level of mastery of another in his or her own sport, recognize a disruptive technology or breakthrough idea when you see it, regardless of the sphere.

Keep your eyes open. Just as a great athlete in one sport can appreciate the level of mastery of another in his or her own sport, recognize a disruptive technology or breakthrough idea when you see it, regardless of the sphere.

![]() Actively solicit ideas and critical analysis from respected innovators in different disciplines. Fresh thinking and a worldview unencumbered by historical interaction may provide just the insight needed to propel an innovation to new heights. Remember, innovation happens best at the intersection of knowledge domains.

Actively solicit ideas and critical analysis from respected innovators in different disciplines. Fresh thinking and a worldview unencumbered by historical interaction may provide just the insight needed to propel an innovation to new heights. Remember, innovation happens best at the intersection of knowledge domains.

![]() Appreciate the power of platform technologies—those capabilities that can be employed in different scenarios and circumstances.

Appreciate the power of platform technologies—those capabilities that can be employed in different scenarios and circumstances.

Fifth-Degree Innovation: Strategic

Cleveland Clinic is always searching for greater ways to fulfill its mission to provide better care of the sick, investigation into their problems, and further education of those who serve. Having just mentioned IBM with respect to geographic innovation, one of the company’s shared values as an organization is to pursue “Innovation that matters, for our company and for the world.”4 When IBM leadership identified the Watson supercomputer as promising a significant difference in medicine, Cleveland Clinic explored a strategic innovation relationship that would leverage the strengths and resources of both organizations.

Beginning in 2002, Cleveland Clinic was an early adopter of electronic medical records. While we strive to remain in the forefront of managing healthcare informatics, challenges have expanded as the body of patient data multiplies exponentially. In addition, our physicians struggle to keep up with the explosion of medical information, which doubles every 18 months. We needed a computing partner to help.

Similarly, IBM needed a healthcare partner to leverage Watson’s cognitive computing, voice recognition, and machine learning capacities to extract pertinent data from the ever-increasing medical literature and simultaneously sift through individual clinical records with a speed and sensitivity exceeding the capability of the caregiver.

For a problem of this scope and impact, it would be hard to find a better correspondence of needs, complementary resource inventory, and understanding of potential barriers. What might have been an exceedingly complex engagement was reduced to the comparatively simple assignment to innovate around specific needs that had been already identified by market leaders using best practices—that is the essence of strategic innovation.

Strategic innovation is the holy grail of the practice; it increases efficiency and accelerates results. Strategic innovation also reduces variables and streamlines the creative development process. Laser-like focus on technology or solution development that fills a recognized need, usually of an eagerly waiting consumer base or partner, is an additional hallmark of strategic innovation. Strategic innovation takes an endeavor typically characterized by frequent failure and challenging algorithmic decision making and makes it more linear, while removing the ambiguity of whether the market will adopt the solutions.

Strategic innovation is the inverse of opportunistic innovation. The latter is a passive rebound of new knowledge that comes the way of the innovator in an unanticipated circumstance. The former starts with collected expertise and robust resources ready to pounce on an already-identified market need.

Another example of strategic innovation is our spin-off CardioMEMS, Inc. With our heart program ranked as best in the nation for 20 consecutive years by U.S. News & World Report, Cleveland Clinic has a strategic priority to continually develop lifesaving cardiovascular technologies. In development of the CardioMEMS system for treating congestive heart failure (CHF), we had three imperatives: (1) replace pharmacologic treatments with a medical device solution, (2) utilize microelectromechanical systems (MEMS) technology, essentially extremely small devices, and (3) find applicability to additional problems.

The CardioMEMS technology was developed by collaborators from Cleveland Clinic and Georgia Institute of Technology. While always targeting treatment of CHF, the technology was first used to sense leaks when an endovascular graft was implanted during abdominal aortic aneurism surgery. Once proof of concept was established with that application, CardioMEMS advanced to its primary objective of managing CHF patients without hospitalization.

A sensor the size of a small paper clip is permanently placed in the pulmonary artery to monitor pressure. Patients take a daily reading from home and send the information to their doctor, who can adjust medication as needed. Previously, such patients would frequently be hospitalized—usually in the intensive care unit—to treat the condition pharmacologically.

St. Jude Medical, Inc., saw the value and purchased an initial $60 million stake in CardioMEMS. Four years later, the company was fully acquired by the global medical technology leader for $375 million.

The development and divestment of CardioMEMS represents the hallmark of strategic innovation: solution development that fills a recognized need among eagerly awaiting customers. The result was introduction of a bold new technology, the first of its kind for treatment of CHF, and its commercial success has been profound.

There is both synergy and synchronicity expressed in strategic innovation that differentiate it from synthetic innovation and build on its foundation. Individuals or institutions aren’t simply joining forces, pooling resources, and comparing notes. Strategic innovation is set in motion by a mature system of problem identification and by market readiness to adopt novel, customized answers.

Recommendations to inspire and capture strategic innovation include:

![]() Establish close relationships with your divestment and transactional partners. Do as much as you can to identify their unmet needs, and then leverage your creative minds to meet the challenges.

Establish close relationships with your divestment and transactional partners. Do as much as you can to identify their unmet needs, and then leverage your creative minds to meet the challenges.

![]() While taking care not to diminish opportunistic and organic innovation, assemble multifunctional teams of experts to participate in structured ideation sessions around specific, market-generated opportunities.

While taking care not to diminish opportunistic and organic innovation, assemble multifunctional teams of experts to participate in structured ideation sessions around specific, market-generated opportunities.

![]() Maintain a list of high-concept, high-impact problems that we all should be pursuing. This innovation bucket list may never be fully achieved but will stimulate the minds of your creatives.

Maintain a list of high-concept, high-impact problems that we all should be pursuing. This innovation bucket list may never be fully achieved but will stimulate the minds of your creatives.

Sixth-Degree Innovation: Telescopic

In 2014, more than 230,000 new U.S. cases of invasive breast cancer were expected, with an additional 62,000-plus new cases of noninvasive (in situ) breast cancer. One in eight U.S. women will be diagnosed with breast cancer during their lifetime.5

If these statistics reflect the numbers afflicted by breast cancer, 100 percent of us are affected by this pervasive disease. I have yet to meet someone who doesn’t have a loved one or friend who has been touched by breast cancer.

Vincent K. Tuohy is a talented and visionary scientist at Cleveland Clinic’s Lerner Research Institute who turned his interests to the prevention of breast cancer. He determined that a specific protein expressed in breast cancer patients was not present in healthy women. From his scientific foundation in immunology, he recognized that the immune system works best at controlling pathologic entities when it can concentrate on prevention and not play catch-up after the disease process has taken hold.

The result is a promising breast cancer vaccine. While the rest of clinical and academic medicine was focused on breast cancer treatment, taking the typical weapons of drugs and surgery into battle, Dr. Tuohy thought differently about the problem to establish a new discipline: adult vaccination against aging-related tumors such as breast, ovarian, and prostate tumors. The implications may be far-reaching. Dr. Tuohy’s new idea has garnered support from members of the philanthropic community touched by breast cancer who want to see the disease eradicated, and CCI spun off a company, Shield Biotech, to further the commercial possibilities associated with this discovery science. Dr. Tuohy’s vaccine is still in early clinical trials and may not be available for a decade.

Similar to Dr. Tuohy, Stanley L. Hazen looked in a different direction, but also looked further and forever changed our understanding of the link between diet and heart disease. Ask virtually anyone about the relationship between eating red meat and developing artery-clogging, cholesterol-derived plaques that limit blood flow to the heart, and he or she will espouse a direct correlation. Even answers from the nutrition and scientific communities would point to excess saturated fat in the diet.

As Dr. Hazen’s work has shown, this blame may be misplaced. It appears that a bacterium in the gut of those who regularly eat eggs, meat, and other animal products readily converts nutrients in those foods to compounds that play a significant role in the evolution of heart disease. In an ingenious experiment, Dr. Hazen and colleagues gave vegetarians and vegans a chemical found abundantly in red meat and dairy products (L-carnitine) and followed the subsequent production of a related compound trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) known to alter the metabolism of cholesterol, curtailing its removal from the bloodstream.

Dr. Hazen recognized that there is a completely different bacterial population in the intestinal tracts of meat eaters and vegetarians or vegans. Even when the non–meat eaters were loaded up with L-carnitine—and some even crossed the line and ate meat—they still didn’t manifest increased levels of TMAO in the short term. Ushering in broad transformational thinking—not only in this field but across many disciplines—is recognition that gut microflora may be the key to unlocking disease processes.

Cleveland Clinic and its spin-off Cleveland HeartLab, Inc. recently announced a collaboration with Procter & Gamble to develop and commercialize a diagnostic and management solution. Cleveland HeartLab will develop a test to measure blood levels of TMAO, while Cleveland Clinic researchers will work with Procter & Gamble to develop an over-the-counter product to help manage TMAO levels.

Innovation is like optics. Opportunistic innovators transition from being creative to becoming inventive by seeing a shooting star. Organic innovators look through a microscope to see how incremental improvements in techniques or technologies can have a magnified impact.

Telescopic innovation embodies two concepts: these innovators literally look through a different lens at problems and solutions, and they combine intelligence with insight to see solutions to big problems in greater detail than others. While their ideas may initially seem like innovation from another planet, entire disciplines subsequently pivot to follow these pioneers. There’s a viral effect as breakthroughs proliferate.

Is Your Organization Prepared to Innovate?

It’s true that innovation—in at least one, if not all of the six degrees—is occurring throughout your organization. But making the most of your organization’s inherent innovation is a challenging endeavor. There must be institutional preparedness to tackle, sustain, and scale innovation.

Before the mantle of “innovative” can be bestowed, an organization must succeed at getting technology developments across the finish line and into the market, or growing the institutional brand by monetizing a core competency through consulting or another form of dissemination of IP.

How is preparedness for innovation determined? Typically, managers compare current and historical data to evaluate where their organization stands, an example being comparison of prior-year and actual financials. A similar “retrospectoscope” is employed to benchmark against regional or even national clinical practice competitors, such as comparing number of new patients seen or amount of funded research.

While there’s no doubt that looking in the rearview mirror can be a logical and useful operations management exercise, evaluating innovation capability is not exactly like calculating EBITDA. Assessing innovation readiness or measuring innovation output demands a balance—contemplating the rearview, but spending most of the time peering through the expansive windshield.

As Cleveland Clinic has organically grown its innovation function over the past two decades, we’ve been pioneers. CCI trailblazers embarked upon the journey without a map and with few other institutions against which to measure our plans or progress. Out of necessity, we had to find a way to examine our own performance and the characteristics of other institutions to determine their present and future promise in this field.

It isn’t reasonable to expect that those running your P&L will automatically share your level of enthusiasm for the part innovation could play in your organization’s future. Recalling that innovation is nonlinear, can be painfully inefficient, and is failure-laden, how can you blame your CFO for getting nervous when you present these factors as normal? Innovation leaders can’t simply ignore requests for data-driven confirmation that they are providing value and executing optimally, despite the normal headwinds that face our practice. The scrutiny directed to performance reporting is greater now than at any time in history because of financial pressures placed on all healthcare organizations (or universities or commercial businesses).

Thus, there’s a growing demand on the part of C-suite executives to measure organizational preparedness to enter into or excel in innovation. Despite the fact that innovation can be expensive and carries with it a high failure rate, practically everyone wants to be in the game. Organizations must consider innovation investment, which has greater inherent risk and delayed reward, against the resource requirements of their core, which delivers incremental growth. Today’s healthcare decisions must be data-driven; for innovation-related metrics, this means technical, cultural, and economic data.

Leaders now have a choice about diving into the deep end of the innovation pool—is it a buy or a build? Stated alternatively, should they seek a partner or go it alone and build an innovation function from scratch? As institutional pioneers in innovation, and as originator of the GHIA, we assumed responsibility for developing instruments to conduct the right inquiry and glean the right information for decisions about innovation execution. In the process, we discovered the optimal way to validate our own practice and choose the best partners for our growing alliance. Following are the tools we developed and employ to evaluate institutional innovation capability and culture.

The Innovation Global Practice Survey (iGPS)

The scholarly literature is dotted with reports detailing innovation capability maturity models (ICMM). These instruments began to emerge in the late 1980s and throughout the 1990s, designed primarily by software engineering concerns, such as the Software Engineering Institute, and sometimes funded by government agencies, including the Department of Defense. ICMMs started to gain more traction in the 2000s, owing to increased scientific rigor and applicability to contemporary R&D functions.

In 2010, CCI’s growth in size, scope, and level of success required us to think more critically about our own cultural and operational assets. We were also experiencing a growing demand to assist AMCs, research universities, and nontraditional partners in industry and government in maximizing their innovation potential.

For these reasons, we sought guidelines from the existing literature, but we strongly believed that industrial models for interrogating innovation capability were not directly applicable to healthcare- and bioscience-sector institutions. Naturally, we sought to fill the void. Not only did CCI need a valid instrument for introspection and benchmarking of our existing function, many of our partners in mission-driven innovation needed one as well to help determine if and how they might enter the innovation ecosystem.

The result was CCI’s Innovation Global Practice Survey (iGPS), a suite of diagnostic instruments that yields objective and subjective data about an institution’s past, present, and future innovation capabilities. Our tool is designed to assess past activity, highlight current status, and forecast future success. It is best when deployed broadly across an organization from the C-suite to the frontline innovator to evaluate the entire organization’s preparedness to innovate. It provides leaders with a playbook that identifies core competencies, practice efficiencies, optimization opportunities, and potential collaborators. The iGPS can be used to track an organization’s growth trajectory or benchmark the organization against its peers of similar size and composition.

The utility of the iGPS resides in its disciplined methodology and ability to reduce variables to metrics. We identified the right variables, quantified them, and weighed the relative importance of selected characteristics. The level of specificity permits innovation leaders to inventory, recognize, rate, and prioritize opportunities. Strategies for improvement in selected parameters can then be furnished by collaboration or consultation.

The components of the iGPS range from the concrete descriptors of innovation architecture to the cultural characteristics that reveal the amount of innovation DNA that resides within an organization. We have validated the instruments through thousands of hours of assembly, interview, analysis, and reporting. The insight gleaned by utilizing the iGPS, as opposed to an undisciplined cursory assessment, has allowed CCI to be a better partner and choose better partners.

The iGPS has four individual components. Each is described in turn.

![]() The Innovation Infrastructure Inquiry (3i)

The Innovation Infrastructure Inquiry (3i)

![]() The Medical Innovation Maturity Survey (MiMS)

The Medical Innovation Maturity Survey (MiMS)

![]() The Graded Perspective Analysis (GPA)

The Graded Perspective Analysis (GPA)

![]() Business Engineering (BE)

Business Engineering (BE)

The sum of these parts has proven to be a valuable 360-degree evaluation of an organization’s place in the innovation universe. As demand grows for institutional leaders to set the innovation course for their holdings, proven tools like the iGPS will be even more valuable.

The Innovation Infrastructure Inquiry (3i)

CCI developed a survey to assess innovation architecture, which we termed, appropriately, Innovation Infrastructure Inquiry (3i). It has become the foundation upon which we build our more sophisticated evaluations.

There are three primary factors to be monitored and maximized to achieve a satisfactory score or rating on 3i: (1) dedicated innovation resources, (2) commercialization processes, and (3) favorable innovation outcome metrics. Additional factors may augment these basics, but without this foundation even the most prolific engines of transcendent thought will prove unsuccessful in presenting solutions to the marketplace.

In 2013, CCI invited dozens of AMCs and research universities to participate in the 3i survey to catalog their innovation profiles. Questions related to licensing revenue, invention disclosures, licenses executed, startups created, patents filed and issued, and commercialization budgets and infrastructure. Results were published in the Medical Innovation Playbook, a CCI publication in collaboration with the Council for American Medical Innovation.6

Perusing the Playbook gives an institution’s innovation leadership a contemporary scorecard that can be used to evaluate and optimize their functions. The goal was not to rank programs or even identify best practices. The goal was to create an unprecedented catalog of the commitment to innovation and present success in delivering breakthrough biomedical advancements.

The reported components also include human and financial resources dedicated to innovation, domains in which creative thought is developing, structure and operation of technology transfer units, and how commercial proceeds are distributed. Following is a summary of the survey results that informed the Playbook. Individual institutional profiles are detailed in the publication.

Operational Characteristics

The overwhelming majority of technology commercialization offices (TCOs) operate as a subsidiary of their parent organizations. Only about 10 percent of innovation functions are independent, some as for-profit spin-offs. This is the structural manifestation of the mission-driven innovation philosophy.

The number of TCOs that derive their funding solely from a direct budget line item in their organization’s P&L is roughly equivalent to those that diversify their funding sources by reinvesting their commercialization revenues (39 percent versus 35 percent). Government grants and various forms of philanthropy are becoming increasingly important to resourcing innovation functions.

One of the distinguishing characteristics of successful mission-driven innovation entities is the commitment to internalize the core capabilities that advance creative thought. In order to translate technologies to the marketplace, proof-of-concept funding is required to accomplish legal, engineering, prototyping, and transactional milestones. Approximately two-thirds of Playbook respondents maintain a dedicated budget for these developmental investments.

Average operating budget per full-time equivalent dedicated to innovation and commercialization is about $232,000 and relatively consistent across the cohort. Twenty-five percent of respondents have an executive or entrepreneur in residence (EIR), a seasoned business expert who may be between opportunities after an early exit and coaches the young innovators and business builders. Some EIRs donate their time or are paid a salary, while others negotiate for equity in the evolving companies they mentor.

Nonprofits can and should engage in the creation of companies that reinforce their mission to improve and extend human life. Some 85 percent of Playbook respondents are at least partially involved in incubation, with 49 percent being the sole entity engaged in startup gestation. Nearly 60 percent of the institutions polled have developed institutional incubators or accelerators to augment the chances for success of nascent companies.

Portfolio Characteristics

HEALTHCARE-RELATED ACTIVITY AS A PERCENT OF KEY COMMERCIALIZATION METRICS

The Playbook cataloged the combined innovation activity of more than 65 AMCs and research universities. This created an overview of nearly 10,000 invention disclosures, 6,400 patent applications, and almost 2,000 issued patents. These translated into 2,600 royalty-bearing licenses, 280 spin-off companies, and $1.5 billion in healthcare/bioscience commercialization revenue. TCOs or innovation functions on the campuses of healthcare systems dedicated essentially their entire commercialization efforts to medical innovation, while multidisciplinary TCOs attribute approximately two-thirds of their commercialization activity to healthcare.

HEALTHCARE INVENTION DOMAIN DISTRIBUTION

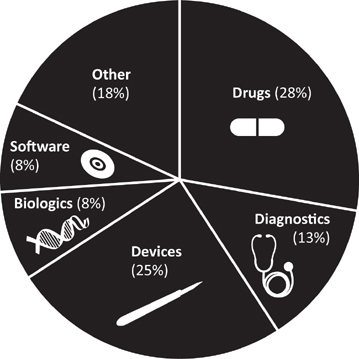

Institutions have distinct capabilities and characteristics and direct their innovation activity accordingly. The typical portfolio includes medical devices, drugs and other “molecules” (diagnostics, biologics, and research assays), and HIT. Many progressive institutions also have developed mechanisms by which the know-how and experience resulting from core functions can be monetized. At Cleveland Clinic, we call this delivery solutions. Many delivery solutions are enabled by HIT platforms.

For example, Cleveland Clinic has traditionally been a strong surgical institution, especially in highly technical subspecialties. This forte also reflects the ethos of the industrial Midwest, which has long been a leader in advanced manufacturing. Therefore, it should be no surprise that medical device innovation, as reported in the Playbook, dominated CCI’s portfolio at 58 percent.

Since the Playbook was published, Cleveland Clinic’s portfolio has grown in number, but it has also broadened in distribution with the amazing growth trajectory of HIT advancements and greater equality between the major technology domains as percentage of invention disclosure. (See Figure 6.1.)

FIGURE 6.1 Healthcare Invention Disclosures by Type. Healthcare invention disclosure by domain among the 60-plus institutions reporting in Cleveland Clinic’s Medical Innovation Playbook.

The Medical Innovation Maturity Survey (MiMS) and Graded Perspective Analysis (GPA)

Innovation can be among the most powerful forces defining individual or institutional success, yet it remains mysterious to many contemporary leaders. C-suite executives know they want their organizations to be innovative and good at it, but many can’t quite get a handle on their own innovation identities.

Recall that every patent or product, each invention and industry, started with an innovation. The question facing C-suite leaders, and especially chief innovation officers, is how to cultivate and sustain innovation to create competitive advantage and serve enterprise mission. How do leaders instill or inspire innovation into their individual colleagues and make its pursuit an enterprise priority and competency?

How the transcendent idea set forth by a creative individual or team is handled makes the difference between delivering a game-changing advancement that helps people (and makes money) and one that fizzles unrequited. It sounds a bit like the age-old nature-versus-nurture debate, parsing the contribution of objective assets like personnel and process against delicate cultural characteristics. Cleveland Clinic believes the correct answer is a hybrid. But we also seek to minimize the frustration and variability associated with balancing the encoded with the elusive.

One of the core competencies that have allowed CCI to grow and succeed is our development of and adherence to disciplined processes to gestate ideas. But we also benefit from a unique environment in which these promising concepts mature. To better understand our own culture and to help colleagues similarly desiring to contribute to the knowledge-based, innovation-driven economy, we sought to better define medical innovation maturity on an institutional level.

We began by building consensus around a working definition of innovation maturity. Our group of professionals from all facets of the innovation community collaborated on the following:

Medical innovation maturity reflects the level to which an organization fosters, supports, and capitalizes on the structural and cultural assets and capabilities associated with developing creative thought to tangible outcomes for the purpose of achieving mission-related goals.

With the foundation in place, we sought to make the assessment of organizational preparedness to innovate in healthcare and the biosciences as objective as possible. The result was our proprietary Medical Innovation Maturity Survey. This simplistically elegant, yet comprehensive instrument interrogates institutional leaders, scholars, and inventors across multiple dimensions of innovation-related variables. The responses are weighted according to their importance and impact on the innovation practice. The utility of the MiMS results from its ability to identify the present status of the innovation culture and recognize pathways to improvement in specific elements or engagements.

The MiMS instrument yields a numerical score (0 to 100) with corresponding subsection scores in three fields: people, process, and philosophy. (See Appendix C for a sample scoring.) Subordinate to the three fields are 17 dimensions that compose a complex mosaic defining innovation in space and time. The process is highly analytical, with a focus on understanding the philosophical and aspirational objectives of all stakeholders who use or influence the innovation infrastructure. The scored survey transforms subjective responses into objective data through the carefully constructed cross-referencing and weighting systems built into the tool. The final score is correlated to a level of innovation maturity that we delineate as entering, engaging, emerging, excelling, or extending.

The MiMS is a 360-degree evaluation of innovation. We’ve found it to be an indispensable tool in three ways. First, it fosters consistent improvement of Cleveland Clinic’s own culture of innovation. Second, it promotes the ability to optimize the GHIA by assisting our existing partners. Finally, it expands our portfolio of offerings to organizations aspiring to participate in the formalized practice of innovation by helping them understand their current status and future potential.

The first cousin and complementary tool of MiMS is the Graded Perspective Analysis (GPA). Aptly named because it applies a letter grade (A–F) derived from the traditional 4.0 scale, the GPA scores the free responses to 10 questions carefully designed to supplement the data gleaned during the MiMS. (See sidebar.) These questions address categories—definition, aspiration, status, legacy, opportunity, responsibility, barriers, recognition, collaboration, and economic development—that contribute to a comprehensive commercialization ecosystem.

Aside from the letter or numerical grade, however, one of the other benefits of the GPA is that it provides direct quotes from innovation stakeholders that can be very informative to those leading or analyzing an innovation effort. In a broader assessment, anonymous quotes can still be related, but ascribed to the interviewee’s level at the organization. For example, alignment or discord between C-suite executives and frontline innovators can be discerned easily through their quotes.

Although the MiMS and the GPA are designed as companion pieces, the GPA can be used alone as a conversation starter around innovation with the uninitiated. It has cultivated a deeper understanding of how intrinsic innovation has become in organizations with mature practices.

The combination of MiMS and GPA has put a very valuable arrow in CCI’s quiver. With these additional results sitting beside the 3i, we can now uncover the previously invisible elements that define the culture of innovation in a healthcare or academic enterprise, or throughout a network of organizations such as the GHIA. Perhaps just as important, armed with identification of specific areas of strength and weakness, CCI can now pick and promote partners in ways that were heretofore unavailable.

Innovation culture is thought to be more like an art, but we have endeavored to add as much science to its assessment as we can. We don’t interfere with the creative process, we interrogate it. These tools have allowed us to bring innovation maturity out of the shadows and into the light, where it can grow and develop into an asset to be managed and shared to better serve the enterprise missions.

Business Engineering (BE)

Business Engineering (BE) completes the quartet of assessment tools under the iGPS umbrella, tools that have empowered CCI to become not only a leading practitioner of mission-driven innovation but also its major purveyor. BE was established to wed entrepreneurial ideas developed outside of our institution or in the GHIA with CCI’s experience in spinning off more than 70 companies. Cleveland Clinic believes providing fledgling prerevenue or early revenue companies with access to its expertise will accelerate market entry and adoption of innovations. Further, the potential to marry elements of our large aggregated IP portfolio to an early or incomplete commercial concern could position our BE clients for sustainable success, thus improving patient care on a global scale.

Opening the BE funnel as an access point to our normal operating platform is logical. We have considerable proficiency in bringing the technologies of our institution and partners to the marketplace, so why not permit access to ideas that gestated outside of our consortium? The offerings of BE include, but are not limited to:

![]() IP review and management

IP review and management

![]() Access to key opinion leaders

Access to key opinion leaders

![]() Business plan support

Business plan support

![]() Leadership and governance identification

Leadership and governance identification

![]() Market analysis and validation

Market analysis and validation

![]() Incubation mentorship

Incubation mentorship

![]() Financial/financing assessment

Financial/financing assessment

![]() Clinical validation

Clinical validation

CCI realizes many benefits from engagement in BE. Chief among them is to refresh our enthusiasm through exposure to the zeal of the outside entrepreneurs who share the mission to extend and improve human life.

In more concrete terms, two facets stand out as the reasons behind opening the aperture to our process and engaging in “intake” rather than just “output.” First, we’re already engaged in the development of spin-off companies; why not get a head start by associating with companies that have moved through the development cycle, albeit from external ideas? Second, the chance to cross-pollinate is compelling; whether by introducing two or more BE clients, adding organic IP we already control, or exposure to emerging entities that can catalyze faster and more voluminous market success.

Given the constant and dramatic shifts in healthcare delivery, reimbursement, and paths to market, many young businesses are finding that going it alone is no longer a viable option for commercialization. A seasoned partner like CCI can help emerging entities avoid the typical pitfalls and hurdles that come with building companies in the healthcare sector. While also providing access to a growing network of investors, corporate partners, and subject matter experts, collaboration with CCI leads to fewer costly delays or misdirected drifts that can challenge the viability of the most fragile startups.

Minding the Gaps

The preceding section of this chapter described our assessment instruments that have allowed us to interrogate the innovation infrastructure and the culture of our organization and any other that wishes to engage with us in the contemporary innovation ecosystem. These exercises have provided us with unprecedented insight into the innovation signature of an organization through which we can interpret the personality and promise of future innovation success.

Like its namesake, the global positioning system, the iGPS really does simultaneously tell you where you are and where you’re going. It has become one of the most important engagement tools in our practice and has allowed us to assist other institutions. The iGPS’s other parallel to the popular navigation aid is that it’s dynamic: the course can be altered to make sure you arrive at your desired destination. When we perform the iGPS and discover an institution’s innovation assets and liabilities, we can then assist in adjusting the pathway by providing advice or resources. We can amplify operational prowess while identifying discrepancies, redundancies, and deficiencies.

We have identified the five most common gaps, some of which exist in almost any innovation infrastructure or institution:

![]() Mission gap. Discord can develop between innovators dedicated to mission and those entrusted with the financial health of an institution. The most common way we have seen this manifest is when the innovation function reports to the CFO, instead of the CEO or research director. We caution any organization that looks at innovation just as a revenue generator and not as an identity builder and mission server.

Mission gap. Discord can develop between innovators dedicated to mission and those entrusted with the financial health of an institution. The most common way we have seen this manifest is when the innovation function reports to the CFO, instead of the CEO or research director. We caution any organization that looks at innovation just as a revenue generator and not as an identity builder and mission server.

![]() Infrastructure gap. In many ways, this is one of the easiest gaps to close. Even when other factors are aligned, there can simply be paucity of professionals familiar with the process of innovation. It’s a highly specific engagement that also requires the ability to deal with several factions: innovators, investors, and industry. The two most straightforward ways to remedy this deficiency are to increase institutional investment in recruitment or seek an alliance such as the GHIA.

Infrastructure gap. In many ways, this is one of the easiest gaps to close. Even when other factors are aligned, there can simply be paucity of professionals familiar with the process of innovation. It’s a highly specific engagement that also requires the ability to deal with several factions: innovators, investors, and industry. The two most straightforward ways to remedy this deficiency are to increase institutional investment in recruitment or seek an alliance such as the GHIA.

![]() Strategic gap. This is an internal mismatch within the C-suite when the nonclinical revenue-producing faction and operational leadership cannot agree on the importance of integrating innovation into the overall enterprise direction. In today’s terms, an attitude of cutting to prosperity has supplanted a balanced approach to managing assets, including exploiting the potential of IP and relationships derived from it. This must be an internal fix that begins with innovation practitioners demonstrating the multiple benefits that innovation creates.

Strategic gap. This is an internal mismatch within the C-suite when the nonclinical revenue-producing faction and operational leadership cannot agree on the importance of integrating innovation into the overall enterprise direction. In today’s terms, an attitude of cutting to prosperity has supplanted a balanced approach to managing assets, including exploiting the potential of IP and relationships derived from it. This must be an internal fix that begins with innovation practitioners demonstrating the multiple benefits that innovation creates.

![]() Capital gap. Successfully funding organic innovation is the most readily recognizable and persistent challenge that all programs face today. The lament from the investment community that what we do can be “too early and too risky” has created a gap between what institutions can fund from their own P&L and what’s required to adequately support the growing company.

Capital gap. Successfully funding organic innovation is the most readily recognizable and persistent challenge that all programs face today. The lament from the investment community that what we do can be “too early and too risky” has created a gap between what institutions can fund from their own P&L and what’s required to adequately support the growing company.

![]() Talent gap. When mission-driven innovation is successful in bringing an idea to the level of company creation, attracting leadership to take the company to the next stage is critical. The barriers to accomplish this are many, but they may be ameliorated by innovation leadership by maintaining entrepreneur-in-training (EIR) programs or working with internal or external incubators or accelerators.

Talent gap. When mission-driven innovation is successful in bringing an idea to the level of company creation, attracting leadership to take the company to the next stage is critical. The barriers to accomplish this are many, but they may be ameliorated by innovation leadership by maintaining entrepreneur-in-training (EIR) programs or working with internal or external incubators or accelerators.

Once gaps are defined, they can be addressed. Combining the ability to identify areas of potential improvement with the competencies to augment deficiencies is the formula for building a sustainable and successful innovation program.