Chapter 8

Listed private equitya

8.1 INTRODUCTION

Private equity vehicles that are quoted on international stock markets are the subject of this chapter. Listed private equity (LPE) are listed vehicles—companies or funds—that offer investors exposure to the private equity asset class. These vehicles pursue a defined private equity strategy (e. g., venture, buyout, mezzanine) and are committed to the private equity investment process in deal screening and selection, structuring transactions, and monitoring and divesting portfolio companies. Underlying investments must be predominantly non-public companies (for more precise classifications of LPE see Bilo, 2002; LPX GmbH, 2008; Partners Group, 2008; RedRocks LPE, 2008; Lahr and Herschke, 2009).

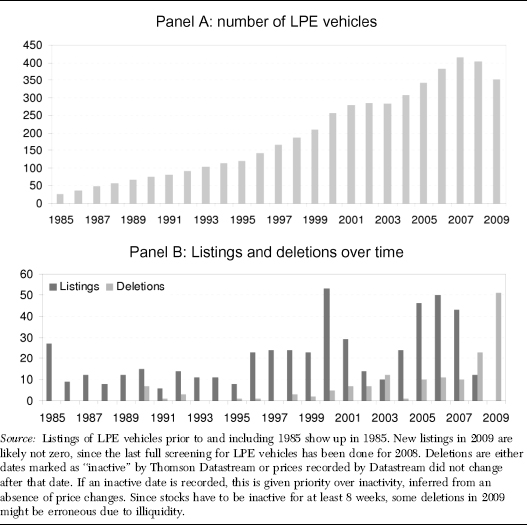

LPE has been around for a long time with the first listings of LPE vehicles dating back to the 1960s.1 Despite these early occurrences, LPE is a fairly new asset class. Exhibit 8.1 tracks listing and unlisting of funds during the 25-year period 1985–2009. Two peaks in the listing of private equity can be noticed from this figure: a surge during the dotcom era and from 2005 to 2007. In 2000, 53 LPE vehicles listed their stock on exchanges, while the latest peak occurred in 2006 when 50 companies went public. Listing numbers in general seem to follow the business cycle. Listings declined sharply in 2007, alongside the overall economic climate. De-listings reached their peak in 2008 when 23 vehicles dropped out. The relative proportion of de-listings is highest for IPOs in 2000, of which 37% have been de-listed since then. Altogether, 20 of all vehicles have been de-listed over the 25-year period, and an additional 10% of the vehicles lack any trading activity. Recent market consolidation left its mark on the total number of listed vehicles which had dropped significantly since its peak in 2007.

EXHIBIT 8.1 LISTED PRIVATE EQUITY VERHICLES OVER TIME: (A) NUMBER OF LPE VEHICLES; (B) LISTINGS AND DELETIONS OVER TIME

Total market capitalization of global LPE vehicles was USD141bn at the end of 2009, a 60% drop when compared with the overal size of USD350mn in early 2000 (see Exhibit 8.2). In terms of geography, most of the listed vehicles are located in Europe. Of the 512 private equity vehicles that have been in existence over the last 25 years, 210 were listed in the U.K., 67 were located in the U.S., and 41 in Germany. Other sizable markets are Israel (21), Australia (20), Canada (19), and Switzerland (16). The average market capitalization amounts to USD300mn with a median of USD32mn as of December 31, 2009. As such, many of the vehicles tend to be small and illiquid. In terms of volatility, LPE market cap shows large swings in excess of equity market movements, which is reflected by the large market betas of LPE (as will be discussed in Section 8.5).

EXHIBIT 8.2 MARKET CAPITALIZATION OF LPE VEHICLES

8.2 BENEFITS AND DISADVANTAGES OF LISTED PRIVATE EQUITY

LPE vehicles offer several advantages over more common LP/GP unlisted private equity funds. These advantages are mainly associated with investors being able to continuously trade shares on regulated public markets. The benefits and drawbacks can be summarized as follows:2

Advantages of listed private equity

- No minimum investment required thereby enables access to retail investors as well as institutions. These investors invest in a portfolio of mainly unlisted companies. In contrast, investing in private equity directly has high minimum commitments.

- Listing provides relative liquidity to an otherwise far less liquid private equity asset class. The typical 10-year time horizon of a fund and the obligation to undertake the unfunded portion of the capital commitment inhibits the size of the secondary market for unlisted private equity positions. In addition, transactions among limited partners are restricted in that they require the consent of the general partner and cannot be legally offered to the public.

- Ability to achieve a wide diversification within the private equity asset class, as each listed fund manager has different investment strategies and criteria.

- Capital gains retained within certain trusts are often not taxed.

- Listed vehicles handle the cash management and administration, which can be complex for limited partnership interests.

- The performance of an investment in a listed private equity vehicle can be easily observed through a quoted price.

Disadvantages of listed private equity

- Potential illiquidity of small closely-held listed private equity vehicles: although technically a holding in a listed private equity company can be bought or sold at any time, there are times when this is difficult to do in practice, especially with large blocks of shares.

- Less control over exposure to private equity investments, since listed funds often invest in instruments other than private portfolio companies.

- Leverage and, therefore, underlying exposure can vary considerably. Listed funds may borrow at times whereas, at other times, there may be a great deal of net cash in the portfolio (e.g., as a result of a number of realizations and a lack of immediate investment opportunities). Surplus cash may act as a drag on performance.

- Shares in listed private equity companies usually trade at a discount or premium to their net asset value (NAV). NAV is necessarily an estimate of the value of the underlying assets—albeit according to strict valuation guidelines—and these valuations are conducted infrequently and with a lag. Shares can trade at a discount to NAV for long periods, particularly when stock market sentiment is depressed or subdued.

8.3 ECONOMIC AND ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS

It should be noted that LPE vehicles can have different organizational characteristics reflecting differences in underlying economics. As opposed to traditional PE, where the vast majority of entities are structured as limited partnerships, the LPE universe is quite heterogeneous with respect to the vehicle’s legal and underlying economic structure.

Listed private funds fall under four main categories (see Lahr and Herschke, 2009):3

— Funds that invest directly in unlisted companies

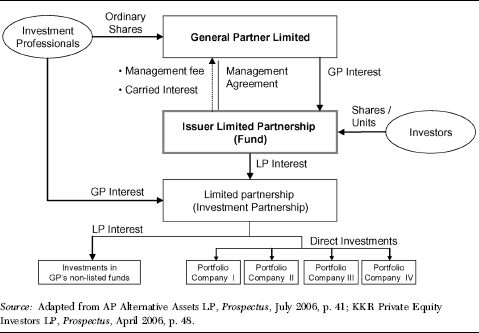

— Funds that invest in companies (henceforth “firms”) that provide investment management for funds (see Exhibit 8.3)

EXHIBIT 8.3 ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS OF LISTED PRIVATE EQUITY

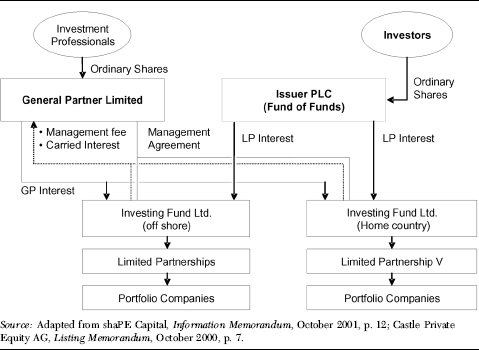

— Listed funds of funds, which offer indirect exposure but higher degrees of diversification

— Investment companies, which invest directly in private companies.

The four groups offer different value generation processes and, consequently, vary in their risk and return profiles. Exhibit 8.4 lists the 20 largest LPE vehicles and indicates for each of them the category in which they fall.

EXHIBIT 8.4 THE 20 LARGEST LPE VEHICLES BY MARKET CAPITALIZATION

Another way to present these distinctions is by grouping the listed vehicles along two dimensions:

— Internally or externally managed companies

— Single or multiple funds.

A further characteristic is the width of the investment mandates. Often, LPE funds are not restricted to invest in private companies, but are allowed to invest in other assets, such as AIM-quoted companies or third-party funds (see Exhibit 8.5).

EXHIBIT 8.5 ORGANIZATIONAL FORM OF A TYPICAL LPE FUND

8.3.1 Funds

LPE funds are externally managed vehicles that invest directly in private companies similar to traditional PE funds (e.g., Electra Private Equity, KKR Private Equity Investors, and HgCapital Trust). From a legal perspective, funds could either be organized as public limited partnerships or be incorporated (PLC, AG, SA, etc.). These vehicles invest their balance sheet, which consists of funds provided by unit-holders or shareholders with the purpose of earning capital gains from investments in private companies.

Similar to conventional traditional private equity limited partnerships, investment management is provided by a third party (i.e., a management company), which is often a traditional general partner. Managers are paid management fees as well as performance-based fees, which are mostly based on net-asset-value returns, but sometimes depend on the fund’s market value. Funds typically invest directly or hold co-investments alongside traditional private equity funds that are managed by the same general partner.

8.3.2 Funds of funds

Funds of funds are externally managed investment vehicles (see Exhibit 8.6). Legally structured as limited liability entities (e. g., PLC, etc.) they pursue investments as limited partners in traditional private equity funds (e.g., Pantheon International Participations and Castle Private Equity). Cash flow is generated from investment activities within the private equity business cycle.

EXHIBIT 8.6 ORGANIZATIONAL FORM OF A TYPICAL LPE FUND OF FUNDS

Similarly to their unlisted counterparts, listed funds of funds tend to diversify across a broad spectrum of strategies: financing stages, general partners (PE groups), fund vintage years, and geographical region. Investments are managed by a management company which is typically paid management fees and carried interest. From an investor’s perspective, these fees constitute a second fee layer between the investor and underlying portfolio investments. However, funds of funds offer access to due diligence expertise and long-standing relationships with private equity groups. For a further discussion see Chapter 7.

8.3.3 Firms

Listed private equity firms are internally managed vehicles that have a similar role to that of general partners in traditional private equity groups (see Exhibit 8.7). However, they typically take the legal form of a standard listed company (e. g. PLC, AG), although partnership structures exist in some cases. Management is rewarded in much the same way as GPs are motivated in private PE vehicles: through management agreements and performance fees (carried interest).

EXHIBIT 8.7 ORGANIZATIONAL FORM OF A TYPICAL LPE FIRM

8.3.4 Investment companies

Investment companies hold a portfolio of direct investments in private companies and are internally managed by professionals. Investment companies come in a wide range of local flavors. Many jurisdictions provide a special legal status to investment companies, such as business development companies in the U.S. and venture capital trusts in the U.K. (see Exhibit 8.8).

EXHIBIT 8.8 ORGANIZATIONAL FORM OF A TYPICAL LPE INVESTMENT COMPANY

Except for their commitment to the private equity business model, investment companies often lack features that distinguish them from ordinary holding companies. They usually report both a consolidated financial statement alongside a detailed portfolio breakdown, which is similar to the reporting of fair values of portfolio investments by listed funds. Portfolios held by investment companies are comparable with those of listed funds. However, investment companies tend to use considerably more debt financing, in much the same way as any conventional company.

8.4 LEGAL FORMS

The organizational forms described above could be obtained through diverse legal structures. Several legal structures that are well suited for private equity investments have emerged, particularly in the U.K. and the U.S., countries where LPE is concentrated.

8.4.1 Investment trusts

Investment trusts are a special type of U.K. investment companies, which invest in securities and whose shares are quoted on the London Stock Exchange.4 Their organizational form classifies them as closed-end fund vehicles. These vehicles have to comply with Section 842 of the Income and Corporations Taxes Act 1988, which states that the company’s income must be derived wholly or mainly from shares or securities, and no holding in a company other than an investment trust represents more than 15% of the trust’s assets. The distribution of capital gains as dividends must be prohibited by the company’s memorandum or articles of association, and the trust must not retain more than 15% of the income it derives from shares and securities every year.

The two main advantages of U.K. investment trusts are their exemption from tax on chargeable gains at the company level and the tax deductibility of management charges.5 The lack of dividend payments can be seen as a disadvantage, in addition to the fact that management charges are subject to value-added tax.

Investment trusts can borrow to purchase additional investments. This ability to take on debt distinguishes them from other collective investment schemes like unit trusts.

8.4.2 Split capital trusts

Investment companies that issue only one class of shares are commonly known as “conventional” investment companies. Split capital trusts (splits) were introduced in the U.K. in 1965 and originally had a limited life with a fixed windup date and two classes of shares: income shares and capital shares.6 The different classes of share are designed to meet different investors’ needs, as they entitle investors to income generated from the investments (income shares) or the capital value of the company at windup (capital shares). Over time, several more share types have developed, such as zero-dividend preference shares. At least one share class within a split capital trust is likely to have a limited life (usually between 5 and 10 years) with a fixed windup date. The different share class priorities and entitlements lead to varying risk levels between these classes. Other kinds of collective investment vehicles cannot offer different share classes within one fund.

8.4.3 Venture capital trusts (VCTs)

Venture capital trusts (VCTs) are a type of company very similar to investment trust companies. They were introduced in the U.K. in 1995 and invest in small potentially high-growth private companies and new shares of companies that are traded on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) and PLUS Market.7

VCTs offer investors income and capital gains tax reliefs, which include income tax relief on the initial investment when subscribing to new VCT share issues, tax-free dividends, and tax-free capital gains. To qualify for income tax relief on subscription, investors must hold VCTs for a minimum of 5 years. These rules governing the tax benefits of VCTs have, however, changed several times over the past years. VCTs have to adhere to several restrictions with respect to the types of companies they can invest in. At least 70% of their investments must be in shares in private U.K. companies which must have pre-money valuations of less than GBP7mn although, prior to April 2006, this limit was GBP15mn. The maximum amount any VCT can invest in a single company in any tax year is GBP1mn. Because of tax benefits and due to their special statutory governance mechanisms, VCTs are sometimes believed to underperform the market on a share price basis (see Cumming, 2003).

8.4.4 Business development companies (BDCs)

Business development companies (BDCs) are publicly traded closed-end companies that are regulated under the U.S. Investment Company Act of 1940, Section 54 (Election to be regulated as business development company) and seek to invest in small and mid-sized private companies. They are required by law to provide support and significant managerial assistance to their portfolio companies. To qualify as a BDC, companies must elect to be registered in compliance with the Investment Company Act. A major difference between BDCs and traditional PE funds is that BDCs allow smaller non-accredited investors to invest in startup companies.

The Investment Company Act imposes certain restrictions on the operations of a BDC. They must hold at least 70% of their total assets in shares of private companies or securities for which there is no ready market, cash equivalents, U.S. government securities, or high-quality debt securities maturing in 1 year or less from the time of investment. Most BDCs have regulated investment company (RIC) status, which requires them to distribute at least 90% of their taxable income to shareholders every year. No more than 5% of their assets can be from a single issuer, and 10% is the upper limit BDCs are allowed to own of the outstanding voting securities of any one issuer. BDCs cannot invest more than 25% of their assets in businesses that they control or businesses that are in similar or related trades or businesses.

8.4.5 Special purpose acquisition companies (SPACs)

A special purpose acquisition company (SPAC) is a shell company (or blank check company) registered with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) which is formed to raise capital for a yet unidentified business that will be acquired in the future.8 Similar to internally managed investment companies, SPACs provide investors with potential access to acquisitions of private companies. They have become a popular new investment vehicle, raising more than USD20bn since 2003 and comprising 20% of total funds raised in U.S. IPOs in 2007 (see Lewellen, 2009; Jenkinson and Sousa, 2009). Moreover, there have been recent listings of SPAC shares in Europe issued as units consisting of common stock and one or two separate warrants that typically can be exercised only if the SPAC completes an acquisition. The warrants, which are normally callable by the firm at any time during the exercise period, may trade separately from the common stock 90 days after the IPO.

After price manipulations in blank check companies (BCCs), the SEC adopted Rule 419, which imposes several restrictions on BCCs, prohibiting trading of the BCC’s securities by requiring them to be held in an escrow or trust account until consummation of an acquisition (see Sjostrom, 2008).9 SPACs avoid the application of Rule 419 by not issuing penny stock. However, SPACs voluntarily incorporate a number of Rule 419–type provisions in their IPO terms. For example, SPAC charters usually require an acquisition within 18 to 24 months after the effective date of the offering. Until that date, 90% of the IPO proceeds must be held in an escrow or trust account. The initial target must have a fair market value of at least 80% of the SPAC’s net assets excluding deferred underwriters’ discounts and commissions. If management does not find a target within a specified period, the SPAC is liquidated and the firm’s net assets are returned to shareholders.

SPACs resemble a risk-free asset in the early stages of their lifecycle, yet many become single-transaction buyout funds if successful. They trade on stock exchanges and invest in private companies and, therefore, may be considered LPE. In order to qualify as LPE, companies must commit to the private equity business model, which includes buying and selling portfolio companies. The selling part is clearly up to the investor. After an acquisition has been consummated, SPACs are very similar to normal holding companies from an economic point of view. SPACs should therefore be excluded from most analyses of LPE on these grounds, as do most LPE indexes.

8.4.6 Structured trust acquisition company (STACs)

Structured trust acquisition companies (STACs) are tax-structured corporate entities that initiate offerings to acquire private companies (see Davidoff, 2008). Similar to traditional private equity fund group structures, investors buy shares in an entity whose sole property is shares in a holding company that invests in private portfolio companies. A management company provides investment services to the holding company. In contrast to SPACs, a STAC identifies its target before going public. Furthermore, STACs enable long-term control-stake ownership of operating companies, and no shareholder approval is necessary for business combinations. They must consolidate financial statements of majority-owned businesses and are subject to “pass-through” taxation instead of entity level taxation of income and capital gains received from portfolio companies. Two STACs have listed their stock so far: Macquarie Infrastructure Company Trust and Compass Diversified Trust, each raising more than USD700mn, which was immediately used to acquire previously earmarked private companies (see Krus et al., 2006).

8.5 ESTIMATED RISK PROFILE OF LISTED PRIVATE EQUITY

As discussed in previous chapters, measuring risk, return, and market correlation are difficult for traditional (i. e., unlisted) private equity investments. The LPE segment lends itself to studying these patterns in a straightforward way using readily available market prices. Since business models and organizational forms of LPE vehicles bear a strong resemblance to traditional PE funds and firms, statistical results obtained from examining LPE vehicles should shed light regarding the broader asset class as well.

However, LPE vehicles exhibit different exposures to market risk depending on organizational forms. In a study of 274 liquid LPE entities, Lahr and Herschke (2009) find that externally managed LPE vehicles exhibit a substantially lower systematic risk than internally managed entities (see Exhibit 8.9). For value-weighted indexes, the estimated beta for investment companies is 2.0 and for firms 1.5. These figures differ from a beta estimate of 1.3 for funds and a mere 0.8 for funds of funds.10 In equal-weighted spread-adjusted indexes, these betas are 1.4 for investment companies and firms, but 1.0 and 0.7 for funds and funds of funds, respectively. The different betas for value-weighted and equal-weighted indexes indicate the impact of a few large volatile investment companies on LPE returns. Betas for the entire LPE sample are 1.8 for a value-weighted index and 1.2 for an equal-weighted and spread-adjusted index. Excess returns (alphas) in these CAPM regressions are generally negligible.

EXHIBIT 8.9 ORGANIZATIONAL FORMS AND RISK (MARKET BETA) OF LPE VEHICLES

In addition to the large variance of betas across vehicles, Kaserer et al. (2010) find that aggregate market risk of LPE vehicles varies strongly over time and is positively correlated with market return variance as given in Exhibit 8.10. Individual betas are found to be highly unstable and are predictable only up to 2 to 3 years into the future. Beta stationarity over time depends, however, on individual fund risk profile. High-risk and low-risk LPEs portray a stationary beta over time, whereas betas of medium-risk companies vary more.

EXHIBIT 8.10 MEAN 1-YEAR BETA

8.6 LPE INDEXES

Several stock indexes based on varying subsamples of the LPE universe have been developed to measure the performance of this sector. ETFs, certificates, and mutual funds tracking these indexes are offered by financial intermediaries such as ALPS Fund Services, BlackRock Advisors, Deutsche Bank, Invesco, Merrill Lynch, RBS, and UBS.

8.6.1 LPX® listed private equity index family

The first and probably best known provider of LPE indexes is LPX GmbH. Since 2004, a family of indexes have been developed consisting of global indexes varying in scope (LPX Composite, LPX50®, and LPX Major Market®), regional reach (LPX Europe, LPX UK, and LPX America) as well as in investment style (LPX Buyout, LPX Venture, LPX Direct, LPX Indirect, and LPX Mezzanine).11 A database of over 300 LPE companies listed worldwide provides the basis for the construction of all LPX indexes.12 In order to be eligible for inclusion, a proportion of net assets greater than 50% must be private companies.

8.6.2 Red Rocks LPE indexes

Red Rocks provides LPE indexes similar to those constructed by LPX GmbH. Their index family consists of three indexes with different geographical focus. The Listed Private Equity Index (LPEI) covers the 25–40 largest and most liquid LPE companies that are traded on nationally recognized exchanges in the U.S. To qualify for inclusion, these companies can invest in, lend capital to, or provide services to privately held businesses. The International Listed Private Equity Index (ILPEI) focuses on 30–50 companies traded outside the U.S., whereas the Global Listed Private Equity Index (GLPEI) comprises the 40–60 most liquid LPE vehicles worldwide. Index constituents must have, or publicly intend to reach, a majority of their assets invested in equity, loans, or services to private companies.13

8.6.3 S&P Listed Private Equity Index

Standard & Poor’s Listed Private Equity Index is constructed from 30 large liquid LPE companies trading on exchanges in North America, Europe, and the Asia–Pacific region, which meet the size, liquidity, exposure, and activity requirements.14 Index constituents are drawn from Standard & Poor’s Capital IQ (CIQ) database and must engage in the private equity business, excluding real estate income and property trusts. Stocks that have an exposure score of 1.0 or 0.5 to PE investments (out of the three assigned values 0, 0.5, and 1.0) are eligible for inclusion.

8.6.4 SG Private Equity Index (Privex)

The Société Génréale Private Equity Index includes the 25 most representative stocks of the private equity companies listed on a stock exchange in Western Europe, North America, Singapore, Hong Kong, Japan, South Korea, Australia, and New Zealand. Constituents must be covered by Dow Jones in the Dow Jones World Index and have their largest revenue share in the private equity sector.15 To be included, companies must be involved in private equity investment activities such as leveraged buyouts, venture capital, or growth capital.

8.6.5 DJ STOXX® Europe Private Equity 20

The Dow Jones STOXX® Europe Private Equity 20 index is constructed to reflect the performance of the 20 largest LPE companies in Europe.16 Constituents must be classified by the Industry Classification Benchmark (ICB) as either “specialty finance” or “equity investment instruments” and/or must have at least 40% of their investments in private equity assets.

8.7 REFERENCES

BERG, A. (2005) What Is the Strategy for Buyout Associations? Verlag für Wissenschaft und Forschung, Berlin.

BERGER, R. (2008) “SPACS: An alternative way to access the public markets,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 20 (3), 68–75.

BILO, S. (2002) “Alternative asset class: Publicly traded private equity, performance, liquidity, diversification potential and pricing characteristics,” Ph.D. thesis, University of St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland.

CUMMING, D. J. (2003) “The structure, governance and performance of UK venture capital trusts,” Journal of Corporate Law Studies, 3 (2), 191–217.

CUMMING AND MACINTOSH (2007) “Mutual funds that invest in private equity? An analysis of labour-sponsored investment funds,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, 31(3), 445–487.

DAVIDOFF, S. M. (2008) “Black market capital,” Columbia Business Law Review, 1, 172–268.

DIMSON, E. (1979) “Risk measurement when shares are subject to infrequent trading,” Journal of Financial Economics, 7, 197–226.

GOMPERS, P. A., AND LERNER, J. (2000) “Money chasing deals? The impact of fund inflows on private equity valuation,” Journal of Financial Economics, 55, 281–325.

HALE, L. M. (2007) “SPAC: A financing tool with something for everyone,” Journal of Corporate Accounting & Finance, 18 (2), 67–74.

JENKINSON, T., AND SOUSA, M. (2009) “Why SPAC investors should listen to the market,” paper presented at AFA 2010 Atlanta Meeting.

KASERER, C., LAHR, H., LIEBHART, V., AND METTLER, A. (2010) “The time-varying risk of listed private equity,” Journal of Financial Transformation, 28, 87–93.

KRUS, C., PANGAS, H., BOEHM, S., AND ZOCHOWSKI, C. (2006) “United States: Taking private equity public,” available at http://www.mondaq.com/article.asp?articleid= 41446

LAHR, H., AND HERSCHKE, F. T. (2009) “Organisational forms and risk in listed private equity,” Journal of Private Equity, 13 (1), 89–99.

LEWELLEN, S. (2009) “SPACs as an asset class,” working paper, available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1284999

LPX GMBH (2008) “Listed private equity index,” available at http://www.lpx.ch (last accessed March 17, 2010).

PARTNERS GROUP (2008) Available at http://www.partnersgroup.ch (last accessed December 17, 2009).

REDROCKS LPE (2008) “Listed private equity,” available at http://www.listedprivate equity.com (last accessed March 17, 2010).

RITTER, J. R. (1984) “The “hot” issue market of 1980,” Journal of Business, 57 (2), 214–240.

SJOSTROM, W. K. (2008) “The truth about reverse mergers,” Entrepreneurial Business Law Journal, 2, 743–759.

a This chapter was co-authored with Henry Lahr (Centre for Business Research, University of Cambridge) and Christoph Kaserer (Center for Entrepreneurial and Financial Studies, TUM School of Management, Technical University Munich). We thank Hans Holman for valuable comments.

1. For example, Capital Southwest in 1961.

2. Based in part on http://www.lpeq.com

3. In practice there is considerable overlap between the groups. Therefore, classifying listed vehicles into categories requires close inspection of portfolios and legal structures.

4. See http://www.aitc.co.uk/Guide-to-investment-companies/What-are-investment-companies/How-they-work/ (last accessed March 17, 2010).

5. See s100(1) Taxation of Chargeable Gains Act 1992 (TCGA).

6. See http://www.theaic.co.uk/Documents/Factsheets/AICSplitsFactsheet.pdf (last accessed March 17, 2010).

7. See http://www.theaic.co.uk/Documents/Factsheets/AICVCTFactsheet.pdf (last accessed March 17, 2010). Similar structures under Canadian Law are labor-sponsored investment funds (LSIFs) and labor-sponsored venture capital corporations (LSVCCs), which are organized as mutual funds and therefore excluded (see Cumming and MacIntosh, 2007).

8. See Hale (2007) for this definition, Davidoff (2008) for a legal description of SPACs, and Berger (2008) for an economic discussion of three case studies.

9. See 17 C.F.R. §230.419(b)(2)(i) & (vi) (2007).

10. For all figures, the Dimson (1979) procedure was used to handle infrequent trading.

11. See Guide to the LPX Indices, February 2009, available at http://www.lpx-group.com/lpx/fileadmin/images/indices/LPX_Guide_to_the_Equity_Indices.pdf

12. See Deutsche Bank, 2005, DB Platinum V Liquid Private Equity Funds, fund brochure.

13. See http://www.redrockscapital.com/lpei_meth.html (last accessed March 17, 2010).

14. See http://www.standardandpoors.com/indices/sp-listed-private-equity-index/en/us/? indexId=spsal-lpe-usdw—p-rgl— (last accessed March 17, 2010).

15. See http://www.sgindex.com/services/quotes/details.php? family=6 (last accessed March 17, 2010).

16. See http://www.stoxx.com/indices/index_information.html? symbol=SPEP (last accessed March 17, 2010).