Chapter 18

Realza Capitala

DECEMBER 2006

It was a cold night in Madrid in December 2006 as Alfredo Zavala and Martin Gonzaález del Valle walked back to the 10-square-meter office they were subletting from a venture capital firm in Madrid. The partners of Realza Capital (Realza), a fledgling mid-market private equity fund, had just returned from the company’s Christmas dinner and things were not going according to plan. Their cornerstone investors, who had verbally committed the initial €40mn for Realza’s first fund, had just called Zavala to say they were pulling out of the deal.

Realza’s goal had been to raise €150mn to €200mn for the fund. The process of raising money was well underway and Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had already built a small team. They had recruited Catherine Armand as administrative assistant and had just convinced Pedro Fernaández-Amatriain to take a risk, forego a steadier career in corporate finance and join them as an analyst. With the promise of future success, Armand joined for free and Amatriain for a very moderate sum for the next 6 months. But Armand and Amatriain were not the only ones with everything on the line. Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had both left lucrative jobs at leading Spanish private equity firms to pursue this entrepreneurial venture, which now appeared to be at risk. Three alternatives presented themselves to the partners. The first was that a major European private equity group was trying to convince them to join and create a south European private equity fund. The second was that they had an indication of a serious offer to become an asset manager for Spain for a high-net-worth individual. The last option was that a major European private equity firm had approached the partners to join as co-heads for a new Spanish office. But while these offers represented viable and immediate alternatives to the founders’ original ambitions, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle needed to carefully weigh all the variables.

Attractiveness of the Spanish Market Landscape

Macroeconomic Environment (2000–2006)

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle realized that the Spanish economy was performing extremely well in 2006 and that the country’s business landscape offered unique opportunities for private equity. Real GDP growth in Spain had averaged 3.7% annually in the period from the first quarter of 2000 until the end of 2006. By comparison, the average GDP growth in the European Union (EU) during the same period had been a little over 2% per year. Spain had almost consistently outperformed its Eurozone neighbors during this time by as much as 3.5%, even during the recessionary period triggered by the “dotcom” crash of 2002 (see Exhibit 18.1 for real GDP growth in Spain vs. EU 2000–2006).

This had not always been the case for Spain. When the country joined the EU in 1986, it was a laggard compared with existing member states and over the next two decades, it received billions of euros in EU development funding to boost growth. Between 1994 and 2005, increased construction investment and private consumption, reduced inflation, high levels of foreign investment, liberalization of the Spanish labor market, and significant immigration fed each other in a virtuous circle of wealth creation for the country.

The low end of the mid-market—the partners’ target segment

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle considered their target segment to be the low end of the mid-market, which consisted of businesses with an enterprise value (EV) in the range of €15mn to €100mn. They recognized that Spain was a land of family-owned, small-to-medium-size enterprises. Many SMEs were facing the challenges of succession planning for the first time in their history. Within this segment, when transactions occurred, they tended to take place without a financial adviser. Financial advisers were only used in 34% of all M&A transactions in the SME segment during 2006, whereas 90% of the 50 largest buyout transactions used a financial adviser.1 In addition, acquisition financing in this segment tended to be sourced from local banks at debt/EBITDA levels which rarely exceeded 3–4×.

The SME segment had many dynamic companies with capacity for growth, but generally these lacked good governance mechanisms as well as financial sophistication. Furthermore, SMEs needed to strengthen their management teams, business processes, and information systems. These types of companies presented attractive opportunities for private equity investors who were prepared to be hands on and to undertake a buy-and-build strategy.

Private equity in Spain

The potential for private equity in Spain was clear to Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle. Spain had a long history of risk capital dating back to the 1970s, but it was in the latter part of the 1990s that private equity and venture capital became significant. The Spanish private equity market grew by a factor of almost 3 between 2002 and 2006. And according to the Spanish Private Equity Association (ASCRI),2 €1,118mn was raised during the first 6 months of 2006, up 107% from the first half of 2005 (see Exhibit 18.2 for PE investment in Spain and Exhibit 18.3 for the number of PE deals in Spain).

EXHIBIT 18.2 PE INVESTMENT IN SPAIN (€ MILLIONS) 1995—2006

Source: Spanish Private Equity Association, ASCRI.

The two partners also knew that the Spanish government recognized the key role private equity could play in helping to develop the country’s economy and improve productivity. In 2005, a private equity regulatory bill was passed through parliament.3It sought to simplify regulation of the private equity industry. In particular, the bill stipulated

- Reduction of the administrative burden on private equity firms and funds

- Expansion of funds’ areas of activity

- Permission to invest in other private equity firms, funds of funds, and public-to-private transactions

- Creation of special regimes for closed-end entities and qualified investors that do not require “small investor” protection rules.

The Partners—Alfredo Zavala and Martín Gonzaález del Valle

Alfredo Zavala and Martín Gonzaález del Valle were both recruited in 1989 by Mercapital, a merchant bank involved in private equity investments and corporate finance. Though they had only casually known each other before joining Mercapital, they had taken strikingly similar directions in life; both studied economics at Madrid University, and then obtained an MBA from INSEAD before moving on to spend some years working in industry (see Exhibit 18.4 for Realza founding partners’ CVs).

EXHIBIT 18.4 REALZA FOUNDING PARTNERS’ CVS—ALFREDO ZAVALA AND MARTíN GONZAÁ LEZ DEL VALLE

In 1995, Gonzaález del Valle left Mercapital to become Deputy General Manager and Head of Investment Banking at Banque Indosuez. Then in 2000, he was recruited as a partner by InvestIndustrial to head and build a private equity business in Spain. Zavala, on the other hand, remained at Mercapital for 17 years, where he became one of the founding partners when Mercapital carried out a management buyout in 1996 before leaving in 2006.

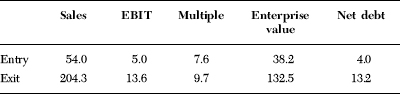

Their combined track record in private equity and investment banking over the years resulted in total investments of €427mn in 22 companies that generated €568mn in proceeds from 16 exits. They led 14 of the 22 deals and exited 10 of these companies. These 10 exits generated an average multiple of 2.9× (see Exhibit 18.5 for the track record of realized and unrealized investments and Exhibit 18.6 for case studies of prior investments).

EXHIBIT 18.5 TRACK RECORD OF REALIZED AND UNREALIZED INVESTMENTS WHERE ZAVALA AND GONZAÁ LEZ DEL VALLE WERE PRIMARILY RESPONSIBLE FOR THE TRANSACTION

EXHIBIT 18.6 CASE STUDIES OF PRIOR INVESTMENTS

Launching Realza Capital

Background, motivation, and vision

One afternoon in November 2005, the two met at the home of Gonzaález del Valle in Madrid to discuss where their respective private equity careers were heading. As they reflected on the opportunities that might follow, they agreed that the environments at their respective firms were changing. As Zavala put it, “Mercapital was moving into the upper end of the private equity market. Martín and I felt we had exhausted our opportunities to grow at our current firms.” Gonzaález del Valle added, “We realized that, at heart, Alfredo and I are entrepreneurs. We wanted to be part of something we could start and build from the beginning.” With this in mind, the two decided to start Realza Capital. “Realza” means “to enhance” in Spanish.4 They felt the name succinctly captured their vision for the new company.

This vision was to create value for investors by leveraging their own prior experience and making primarily control investments in Spanish SMEs. Initially, they sought to raise €150mn for their first fund, with a target portfolio of 8 to 12 companies. The equity investment was expected to be anywhere from €5mn to €25mn per portfolio company. As a key feature, their strategy for creating value was not based primarily on leverage. Within a segment comprised of companies sorely lacking in management expertise, they sought to bring their significant operating experience to bear, moving their portfolio companies into “the next stage of their development”.

Strategic positioning, organization, and team

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle chose to focus on the SME segment described above for a number of reasons:

- Companies in this segment accounted for a significant portion of the economic “value-added” in Spain (see Exhibit 18.7 for “value added” by SMEs within the Spanish economy).

- Both founders had spent the majority of their careers building a successful track record in this segment.

- The vast majority of companies in this segment were family owned, lacking sophisticated operational strategies, processes, and structures; therefore, this segment represented an opportunity to add value upon acquisition.

- Deal transactions in this segment were most often proprietary (as opposed to auctioned) deals, thus offering the opportunity for more favorable acquisition prices.

- The sheer number of companies in this segment ensured a wealth of “buy and build” investment opportunities and a good quality deal flow. Both partners were familiar with this type of investment, given their prior experience.

- There was virtually no competition in this segment, either from Spanish funds (very few with comparable experience) or international funds.

Once a fund was successfully raised, the partners anticipated having a team of six investment professionals (two partners, two investment managers, and two analysts) and two administrative staff. As the number of companies in the portfolio were to grow, the partners planned to strengthen the team accordingly, intending to hire an additional investment manager and analyst within 2 to 3 years after Realza’s final closing.

Another crucial component of Realza’s organization was an informal advisory board, comprised of a network of seven to ten senior managers and sector experts with whom Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had worked in the past. For each portfolio company, one or more members of this board would be designated to support the team in reviewing the due diligence and executing the business plan. These professionals would be compensated via a combination of “directors’ fees”, stock options, and the opportunity to participate in the investments in which they were involved.

Competitive landscape

In Spain, the private equity market in 2006 was stratified into three levels (see Exhibit 18.8 for an illustration of competitive landscape). The first tier was a large buyout fund, which targeted investments greater than €300mn in EV and was represented by global organizations with operations in Spain. This highly competitive tier was populated by both top-tier U.S. and pan-European funds.

EXHIBIT 18.8 ILLUSTRATION OF COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE

Source: Capital & Corporate Magazine and Realza Capital.

The mid-level competitors were a more mixed group. Some global organizations such as 3i rubbed shoulders with the larger Spanish firms—Mercapital being a prime example. Deal sizes ranged from €100mn to €300mn in this mid-level. Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had observed that the size of these organizations’ deals had been increasing significantly, and that more of them were being completed through advisers and auction processes.

Finally, the closest competitors to Realza were the small buyout funds, typically targeting €100mn or less in deal size. In this segment, having a strong local team and network was vital for deal origination. As the partners recognized, competition was limited in this space.

Realza’s investment strategy

During their time in private equity and industry, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had developed an extensive network that gave them excellent access to the business community in Spain. As their former firms moved away from the smaller transactions, the newly formed Realza could capitalize on the opportunities in the market that were left behind. In particular, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle directly approached the intermediaries they had dealt with before, given their deep expertise in the smaller transactions that no longer interested Mercapital and InvestIndustrial.

Realza’s strategy was to invest in buyouts in the low end of the mid-market in Spain. 76% of Spanish companies are family owned and 97% of companies have a headcount greater than 10, but less than 200. The partners felt strongly that this strategy offered some uniquely attractive opportunities. The SME companies are generally less structured, which allows experienced investors to make a significant contribution to value creation by working closely with the existing management teams.

Realza shared the view, which is widely consistent in PE, that creating value by providing not only financial, but also strategic business partnership was the key. Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had also proven themselves to be adept at this. Exhibit 18.9 illustrates how the partners created value during the 22 investments they were involved in prior to forming Realza. Business plan development and implementation, professionalization, and strengthening of management were persistent themes, even more so than execution of the acquisition and financial restructuring. From the outset, it was agreed that Realza would not invest in startups or distressed companies. Family-owned, SME enterprises seemed to be the right fit.

EXHIBIT 18.9 VALUE CREATION BY ALFREDO ZAVALA AND MARTIN GONZÁLEZ DEL VALLE IN PRE-REALZA INVESTMENTS

The partners determined that Realza would invest with a target outlook of 3 to 5 years, a reasonable period in which to generate value. Disinvestment in companies would principally be through sale to strategic (trade) buyers and, to a lesser degree, through secondary transactions to private equity (financial) investors interested in furthering the business project underway and supporting the management teams.

The return on investment was to be achieved through the following factors, listed here in order of importance to Realza:

- Expansion of operating profit (EBITDA), through organic growth and acquisitions.

- Increase in the EV/EBITDA multiples, compared with the corresponding multiples paid at acquisition. While GPs in general have little control over market multiples, these multiples usually reflect expected growth opportunities for the company and GPs do have control over improving the company’s ability to pursue these growth opportunities.

- De-leveraging/Financial restructuring—using the cash flow of the business to pay down a portion of the debt on the company’s balance sheet.

Realza’s investment process and portfolio management

Realza’s investment process would involve the deal team (one partner, one investment manager, and one analyst) visiting the potential target, deepening their knowledge of the company, and writing a “preliminary investment memorandum” on the opportunity. Once the potential deal was agreed internally, a “letter of intent” would be issued between Realza and the target company, giving Realza a period of exclusivity on the deal (around 3 months, but varies from deal to deal). Realza would then conduct the more costly, in-depth due diligence on the company, before completing the deal.

The intention of the partners was to have the same team that did the acquisition remain in place to monitor and manage the investment, and eventually to undertake any buy-and-build acquisitions. Realza would also work very closely with its Industrial Board in this regard.

Conclusion

Just after 2 A.M., Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle resigned themselves to returning home to try and get some sleep. The following day they would need to begin re-engaging vigorously with potential investors. How should they promote the fund and reach the right investors? Would they be able to successfully close the fund and achieve the €150mn to €200mn target size? Or should they more seriously consider, for the sake of stability for themselves and their team, the three alternatives that currently were available to them?

Madrid was just coming to life with evening revelers braving the cold as they walked to their cars. Although the partners had a clear vision of where they wanted Realza Capital to go, they knew they were still far from being able to celebrate success.

DECEMBER 2008

As Martin Gonzaález del Valle and Alfredo Zavala (the partners) discussed where to hold Realza Capital”s Christmas party in December 2008, they reflected on the events of the past 2 years. They recalled how grim the mood had been at their Christmas dinner in late 2006. Key investors had withdrawn their commitments and a wealthy family had offered the partners a fallback from their dream of setting up and running their own, independent fund.

How times had changed since then. At the end of 2005, they resolved to create Realza Capital. By the end of 2006, they had made three further decisions; first, to reject the alternative offers that had presented themselves. Second, despite a difficult beginning they had decided to pursue an international base of limited partners (LPs) rather than just domestic Spanish companies. Third, in order to successfully attract international LPs and raise funds, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle engaged a placement agent. Just 3 months ago, Realza had completed its fourth and final closing. Overall, the fund had raised €170mn, well within the desired range. The mood within the firm as 2008 came to a close was buoyant.

Yet, as they entered 2009 the partners knew there were new challenges on the horizon. The Realza team, so intensely focused on fundraising until now, needed to quickly shift gears into “investing and operating mode” and start realizing value for its investors. This would have to happen against the backdrop of a deteriorating economic climate in Spain. The country was now truly starting to feel the effects of the global financial crisis.

While the turn of the year was surely a time to celebrate the achievements of the past 2 years, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle knew that the real challenges still lay ahead.

Placement agents

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle knew that private equity funds often use placement agents, or intermediaries, to connect them with investors. The agent is typically compensated based on a percentage of funds raised. The agent’s role includes

- Working with the partners of the fund to create investor due diligence materials, including a private placement memorandum (PPM), sales presentation, due diligence questionnaire (DDQ), and references to support the partners” track records

- Finding potential investors, primarily through personal contacts

- Scheduling the investor “roadshow”, a process whereby the partners (usually accompanied by the placement agent) “sell” the fund to potential investors

- Providing advice and support to the partners on how to effectively present the investment opportunity during the roadshow.

The larger the fund being raised, the larger the placement agent because typically larger agents work with the bigger investors that large funds are targeting.

Etienne Deshormes and Elm Capital

Etienne Deshormes, a native of Brussels, had a diverse career including managing directorships at both JP Morgan and later Zurich Capital. He also had a short stint founding an internet startup, just before the dotcom crash, to help corporations select financial advisors (see Exhibit 18.10 for Etienne Deshormes’ CV).

EXHIBIT 18.10 ETIENNE DESHORMES’ CV

After the demise of the startup, Deshormes had been considering his next career move, when a former colleague approached him to ask for help in raising money for a first-time fund in Italy. The venture was challenging but ultimately successful, with the fund closing within 6 months of Deshormes becoming involved in the process. He realized that a gap existed in the market for a placement agent with his background and a track record in raising money for first-time funds As Deshormes put it, “First-time funds have no existing investor base or direct track record to leverage … and this is a difficult story to tell to relatively risk-averse investors. In addition, raising a country-specific fund is tough, as there are fewer investors with an allocation in their portfolio for country-focused investments.” With this in mind, Deshormes established Elm Capital in 2001 and went on to place a further six funds, before being introduced to Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle by a mutual acquaintance.

Realza engages Elm Capital

In November 2006, Deshormes flew to Madrid to meet with the partners of Realza. Deshormes recalls, “As I sat in their sublet office, I noticed that the main meeting room was also the only route for everyone in the office to get to the bathroom … I hoped that they had an alternative meeting room for visiting investors! Nevertheless, the meeting was great and I felt confident that I could work with Martín and Alfredo.”

As he boarded the flight back to London, Deshormes reflected further on the appeal of working with Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle. He recalls “Both Alfredo and Martín had significant experience in the Spanish market, and a strong track record and reputation in the mid-market in particular. In the context of the Spanish economic environment at the time, I felt that the best deals [in terms of potential to create value] were the smaller ones. Also, given that larger private equity funds in Spain had recently shown pretty erratic performance, I felt that investors were looking for a fund with this type of focus.”

Meanwhile, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle also considered their options. In the European marketplace, they assessed the merits of working with placement agents across the three broad tiers:

- Large market (large funds, typically more than €1bn in funds raised)—examples included Credit Suisse, Merrill Lynch, and UBS.

- Mid market (mid-size funds, typically €500mn to €1bn in funds raised)—examples included MVision, Campbell Lutyens, Helix, JP Morgan Cazenove, and Lazard.

- Small market (small funds, typically less than €500mn in funds raised)—examples included Capstone, Accantus Advisers, Triago, and Elm Capital.

Although Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle felt they would get more attention and focus from a smaller agent, they realized that one possible downside of working with a smaller agent could be lack of resources to dedicate to producing due diligence materials for potential LPs. However, in the case of Realza, this was less of a concern, as the partners had already generated most of the required information.

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle decided to partner with Elm Capital as a placement agent and quickly settled on terms. As per the typical placement agent model, they agreed that Elm would get compensated via a fee based on a percentage of funds raised. As it turned out, Deshormes and Elm would spend the ensuing 18 months working exclusively with Realza.

Overview of the fundraising process

Deshormes outlined the fundraising process to the Realza team, taking them through the following three broad phases:

- Preparation of due diligence materials

- Conducting the roadshow

- Conducting follow-up meetings and finalizing terms with the LPs.

Preparation of due diligence materials

Deshormes explained to Realza that there are certain documents investors typically require to enable them to make a decision on whether to invest in the fund. These include a presentation for the roadshow meetings, a private placement memorandum (PPM), a due diligence questionnaire (DDQ), and references for the partners of the fund. The partners and the placement agent typically work together in preparing these materials and, where possible, customizing them to address particular investor “hot buttons”.

The roadshow presentation is typically a slide presentation outlining the macroeconomic and competitive landscape, the partners’ motivations for setting up the fund, the fund’s investment strategy and structure, and the backgrounds of the key investment professionals working for the fund. Deshormes knew from experience that a crucial piece of the background of the founding partners is their track record. A significant portion of the presentation is usually devoted to describing the track record, both at an overall performance level over their careers and for each deal separately. The goal of the presentation is to excite potential investors in the relatively short period of time available at the introductory roadshow meeting. Typically, the PPM is a more detailed, “leave behind” booklet version of the presentation, while the DDQ aims to answer all further questions a potential LP might have. Exhibit 18.11 contains an outline of the key topics covered in Realza’s PPM and DDQ.

EXHIBIT 18.11 OUTLINE OF THE CONTENTS OF THE PRIVATE PLACEMENT MEMORANDUM AND DUE DILIGENCE QUESTIONNAIRE

Deshormes was impressed by the fact that Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle prepared many of the presentations and the due diligence material in advance. This reflected well on their professionalism and understanding of the private equity process. They were also aware that potential investors want to see references and gathered the information from several CEOs of the portfolio companies with whom they had worked in the past, two of which are shown for illustration in Exhibit 18.12.

Conducting the roadshow

Deshormes played a key role in contacting target investors and arranging the roadshow for Realza. Through his network, Deshormes approached close to 300 potential LPs. Deshormes, Zavala, and Gonzaález del Valle were soon on the road; they embarked upon an intensive 3-week European trip, meeting more than 40 potential investors in 16 countries. Typically, the Realza partners were the main presenters on the day, with Deshormes playing the main role before (preparation, packaging, tailoring the messages, and delivery) and after the meetings (providing feedback).

After each roadshow presentation, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle sent investors who had expressed an interest a copy of the DDQ and, facilitated by Deshormes, followed up with the investors regarding specific queries. Once their interest became serious, the investors were invited to visit Realza’s office in Madrid and spend the day with Zavala, Gonzaález del Valle, and their team.

Deshormes recalls some of the concerns prospective investors had at the time. “They were concerned about attribution. How much of the value that Alfredo and Martín had created had been due to them as opposed to market conditions, leverage, or other factors? And how much of it was accurate? We had to show them numerous references from the CEOs with whom the partners had worked. And, even if the track record was to be believed, there was some concern around the fact that the partners had been in the private equity market for about 20 years and had only completed 22 deals. Finally, there were some reservations expressed about the ability of Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle to work together to reproduce their track record. The two had of course worked together before, but that had been quite a long time ago.”

Deshormes and Realza knew that, after the office visit, potential investors who wanted to proceed usually had to present the opportunity to their own investment committees, often multiple times. During this process, Deshormes and the partners did their best to answer questions and support these internal presentations. Once the prospective investors gained approval from their internal committees, the lawyers representing Realza and the potential LPs would meet to hammer out the term sheets and legal agreements (Exhibit 18.13 provides a summary of principal terms for Realza).

First investment and fund closing

By the spring of 2007, Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle knew it was going to be important to demonstrate to potential investors that Realza had the right network of contacts to originate a solid deal flow in the SME segment. Zavala put the issue succinctly: “Without the money you can’t do the deal, but without the deal you may not be able to attract the investors and close.” Clínica Perio, Spain’s largest chain of high-end dental clinics, offered just such a chance for Realza.

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle found the dental market in Spain highly attractive. First, it had demonstrated double-digit growth consistently for the past two decades. Second, it was highly fragmented with 24,000 dentists and 14,000 clinics (i.e., an average of 1.7 dentists per clinic). Realza’s investment thesis was to consolidate the market by building a national chain. Such a chain would enjoy massive scalability of common back office and procurement. Furthermore, existing clinics lacked the ability to borrow money and, therefore, were unable to reduce their cost of capital. Clearly, a national chain would be able to enjoy far superior terms. Finally, the rationale for acquisitions was supported by the lack of a secondary market for selling or buying clinics.

The Clínica Perio opportunity also demonstrated an ability to be a majority investor alongside existing management. Realza negotiated to acquire 62% of the equity from its three founders, who reinvested to take the remaining stake.5 Realza signed the stock purchase agreement (SPA) with Clínica Perio (subject to due diligence) on July 10, 2007.

Unusually, Realza actually signed the SPA prior to the first close (hence before being able to make the actual capital call). However, this was not as risky at it might appear, as the only step remaining to complete the first close was final approval for the fund’s incorporation from the Comisioán Nacional del Mercado de Valores (CNMV—the Spanish financial services regulator). Most of the soon-to-be LPs had already signed letters of commitment and the SPA for Clínica Perio contained a clause making the deal contingent upon a successful first close.

With an investment under their belts, the Realza Capital story became a more tangible proposition to potential investors. A €43mn first close in August 2007 was followed by a second close at €87mn in January 2008 and a third close at €142mn in May of the same year. Meanwhile, the overall economic picture in Spain had continued to worsen. Real GDP growth in Spain had been vigorous since 2003 but by 2008 forecasters were expecting to see the first contraction since 1993. The housing sector was showing significant signs of decline and the levels of corporate debt across the Spanish economy were at almost 115% of total GDP. Despite these concerning signs, demand from investors for Realza’s fund meant they were able to exceed their target €150mn and reach €170mn by the final close in September 2008.

Conclusion

Gonzaález del Valle and Zavala knew the Realza team had accomplished a tremendous amount over the past 2 years. The partners had begun with an ambition to start their own fund and stay independent, and had stuck to their guns in the face of investor withdrawals and fallback options they really did not want to entertain. They successfully raised €170mn, well within their original target range.

But meanwhile, Spain was not immune to the global financial crisis. Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle were acutely aware that Spain was beginning to show the telltale signs of an overheating economy. The country was entering a new phase in its downturn, and it was in this context that Realza needed to shift from “fundraising mode” to “investing and operating mode” to start delivering value to its LPs; and they needed to do this quickly.

Would Realza have the right balance of skills on their team to source and invest in portfolio companies in the current environment? Would the managers on their Industrial Board have the right skills to create value within the portfolio companies during a time of considerable economic distress? And how might the evolving (largely worsening) macroeconomic conditions impact the exit strategy for their portfolio companies?

Zavala and Gonzaález del Valle had much to think about as the winding road of 2009 stretched out ahead of them.

a This case was co-authored with Jo Coles and Vijay Sachidanand (Executive MBA 2009). We have benefited from valuable comments by Jim Strang (Jardine Capital) and Hans Holmen (Executive Director, Coller Institute of Private Equity, London Business School).

1. Source: Thomson Financial Research, 2006.

2. ASCRI, founded in 1986, states its purpose as “representing, managing and defending the professional interests of its members, as well as promoting and encouraging the creation of entities whose objective is the taking of temporary stakes in the capital of non-financial enterprises that are not quoted on a stock market.”

3. Law 25/2005 simplifies the regulatory burden, allows acquisition of listed firms in order to de-list them, and permits the creation of private funds of funds aimed at institutional investors.

4. The word also has “regal” implications; real means royal in Spanish.

5. No debt existed on the company’s balance sheet or was used to finance the investment.