Chapter 25

Ducati and Investindustrial:Racing out of the pits and over the finish linea

It was a clear sunny day on June 5, 2010 in Mugello, Italy as Andrea C. Bonomi, the founder of Investindustrial, watched Team Ducati clinch the first place at the 2010 Moto GP Gran Premio D’Italia qualifications. As he ducked out of the stadium to head back to Lugano, Switzerland, Bonomi’s mind moved away from Ducati’s success on the track to its performance as an investment. Many events had transpired since Investindustrial uncharacteristically invested in a listed company by buying a stake in Ducati in 2005. At that time, the legendary bike manufacturer was on the verge of bankruptcy. Overleveraged and fraught with cash problems, Ducati was about to default on its existing loan obligations as the bank was unwilling to restructure the debt. Investindustrial rescued the company by injecting cash and taking over the remaining 30% equity stake of the Texas Pacific Group (TPG).

Over the next few years, Bonomi employed his hands-on style to effect a “revolution” inside the company that turned Ducati’s financial position around. The changes also unleashed the passion for innovation that Ducati had always been known for and the company began revamping its dusty product line.

In 2008, as the financial crisis started to unfold, Bonomi had a choice to alter his investment in Ducati. He was contemplating his options of exiting the investment, buying the remaining 70%, or maintaining the 30% stake.

Investindustrial was the brainchild of Bonomi who started the fund in 1990 after identifying an unmet need for private equity capital in Southern Europe, particularly in Spain and Italy. He explained:

“I noticed that the GDP of Spain and Italy combined is 1.5 times that of the U.K., yet the PE investments in these countries were less than 20% of that in the U.K. And these economies are about as advanced as the U.K. so there was a tremendous opportunity and I wanted to help create that market and lead it.”

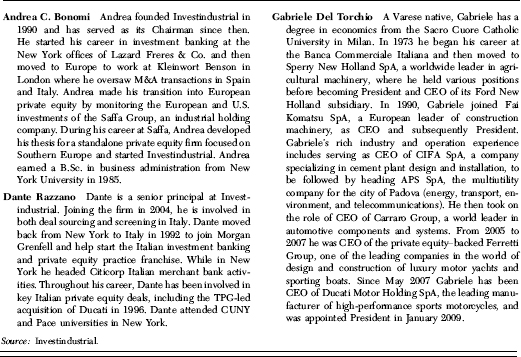

In the course of two decades, Investindustrial raised over €2bn to make 44 investments. With a team of 50 people focused on taking control positions, Bonomi made investments between €35mn and €200mn in companies with revenues of up to €1bn. A long-term investment horizon and an industrially driven approach had established Investindustrial as the leaders of private equity in Southern Europe. As of late 2010 Investindustrial had realized 28 exits generating a gross IRR of 39% and a money multiple of 2.4 × with just one writeoff. The firm had built a successful and consistent track record through a focused investment strategy and by maintaining a moderate debt level—typically below 3 × EBITDA—as a cushion against significant changes in the marketplace. Details of Investindustrial’s strategy, investment team, fund history, and current status are given in Exhibit 25.1.

EXHIBIT 25.1A PROFILES OF KEY PERSONNEL AT INVESTINDUSTRIAL AND DUCATI

EXHIBIT 25.1B INVESTINDUSTRIAL’S EVOLUTION 1990–2010

EXHIBIT 25.1C INVESTMENT PORTFOLIO OF INVESTINDUSTRIAL

Inspired by the infamous radio inventor and Bologna native, Guglielmo Marconi, the Ducati family began producing radios in the city in 1926. Building upon the initial success to invent new types of cameras, movie projectors, and other appliances, the business outgrew the family villa to eventually become the second largest manufacturing concern in Italy. Forced to retool their production facilities to meet the needs of the Italian government during the Second World War, Ducati became a repeated target of Allied bombing and was razed to the ground in 1943. Barely a month after the war, the Turin firm SIATA mounted a small pushrod engine on a bicycle and named it the Cucciolo (Italian for “puppy”, in reference to the distinctive exhaust sound). As the economy was recovering, The Cucciolo started to replace manual bicycles as the preferred driving vehicle for businessmen across the country. In 1950, Ducati produced its first motorized bicycles, a 60, cc bike with a tiny 15,mm carburetor delivering 85,km/L.

However, following years of hardship, the founders were left penniless and the company was rescued by the Italian government through the Institute for Industrial Reconstruction (IRI). Under IRI, the company was split into two concerns: Ducati Energia, a consumer electronics company, and Ducati Meccanica, the motorcycle company. It was Ducati Meccanica that created the Cucciolo. What really put Ducati on the map was the engine designed by Fabio Taglioni. The avant garde Taglioni design, also called the desmodromic distribution system, was partially designed out of necessity. As quality steel was unavailable in the postwar period in Italy, Taglioni invented a new type of engine that could allow valves to open and close at high revolutions without the use of springs. Over the next 40 years Ducati established itself as the premier Italian manufacturer of racing motorbikes.

In 1983 the Italian state suffered significant losses on Ducati due to management issues and sold the company to the Italian conglomerate Cagiva. Cagiva stood for “Castiglioni Giovanni Varese”, and was named after the founder and the town in which the company was based. While producing its own motorcycles since 1979, Cagiva had great frames but no engine whereas Ducati had a great engine but not an outstanding body. When the two were put together, the Ducati of today was born. Run by the Castiglioni brothers, Cagiva became an organization passionate about building world-class motorcycles. Giving the engineers free reign, the brothers enlisted a design group in San Marino, a principality 85 miles from the Ducati headquarters in Bologna, to create a portfolio of bikes. The team in San Marino, driven by independent-minded designers and engineers, operated in total secrecy. Castiglioni was given very little information on the kind of bike that was being built or the timeline for the release but was simply asked to meet the ongoing funding requirements. One of the bikes this team developed was the Monster motorcycle.

The Monster, with its revolutionary minimalist design, was a runaway hit becoming Ducati’s biggest selling bike in history. In spite of success in the marketplace, Ducati suffered from serious financial and management issues. Ducati’s marketing budget was a fraction of that of its competitors and its distribution channel comprised motorcycle enthusiasts who were not focused on maximizing sales or profitability. Ducati still operated like a family business with limited financial controls and poor corporate governance.

In 1996, after a challenging negotiation with the Castiglioni brothers, TPG made their debut European transaction by acquiring a 51% stake in Ducati based on the Italian lira equivalence of USD420mn transaction value of which two thirds (USD280mn) were financed by debt.1 The TPG acquisition was completed in 1998 to make the American private equity group the sole owner of Ducati. On the operational side, TPG recruited Federico Minoli, a former Bain consultant and executive of Benetton U.S.A., to run Ducati. Setting branding as a priority over fixing operations, the first move Minoli made after taking over the beleaguered company was to build a museum; an act that caused the workforce to promptly go on strike. That first day set the tone for the next 7 years. Focused on telling a unique story to fend off intense competition from the Japanese, Minoli positioned the Ducati brand as the Ferrari of motorbikes. In a few years, “the red motorcycle from Borgo Panigale” became synonymous with high-end racing performance and Italian style.2 TPG took Ducati public in 2000 and exited partially, leaving it with a residual 30% controlling stake in the company.

The successful turnaround and IPO gave TPG the credibility in Europe to raise its first European fund. As TPG shifted its focus towards making investments from the new fund, Ducati began to show signs of weakness. Minoli brought much needed marketing skills to augment the engineering background of Castiglioni’s Ducati; however, over time the company began to move away from its core competency of making great bikes. De-emphasizing product innovation, Minoli only launched one new bike during the TPG years. For a new concept, Minoli hired the best consultants to conduct extensive market research to determine the exact product that would meet customer needs. The idea was to create a bike that was low enough for women to ride but high enough for the road—a model that had enough of a new body to be deemed new, yet given financial constraints used the same technology as existing bikes. The 999 model was Ducati’s biggest flop. Looking more like a mainstream Honda than a Ducati, customers perceived the 999 as a bike of compromises without Ducati’s trademark passion. The company later realized that customers do not want—in Bonomi’s words—“A bike that is quiet, reliable, smooth and powerful. They want a Ducati made by a bunch of crazy passionate engineers. If it burnt your leg a little, well, isn’t that cool?!” (see Exhibit 25.2 for Ducati relevant market segments and Exhibit 25.3 for customer perception of motorcycle brands in 2005).

EXHIBIT 25.2 MOTORBIKES MARKET SEGMENTS

EXHIBIT 25.3 CUSTOMER PERCEPTION OF LEADING BRANDS IN 2005

INVESTINDUSTRIAL ACQUISITION OF DUCATI

For nearly 3 years investment bankers had repeatedly urged Investindustrial to acquire Ducati. Conceptually, it made perfect sense—Ducati was a famous Italian brand and Investindustrial was a leading private equity firm in Southern Europe. However, Bonomi questioned the upside potential since TPG had extracted the turnaround value. He was also concerned that buying a stake in a publicly listed company would likely limit the ability of Investindustrial to drive a proper repositioning process. Third, there was a free-riding problem where some of Investindustrial investors might have wondered why they couldn’t directly invest in the listed shares of Ducati, thereby avoiding Investindustrial management and performance fees.

Situated at the heart of the financial community of northern Italy, it was no wonder that Bonomi had close personal connections with Ducati. He repeatedly received calls from friends who sat on the board of Ducati and others close to the company to look at it on the grounds that it was a great opportunity as the company was mismanaged. Internally, Dante Razzano, a senior principal at Investindustrial who had helped TPG to acquire Ducati in 1996 and served on its board, also started to see a new opportunity emerge. Investindustrial, however, declined all invitations to invest.

The turning point came in January 2006 when a leading Italian merchant banker from Mediobanca known for his frugality insisted on taking Bonomi to the most expensive restaurant in Milan. “The company must really be in trouble,” thought Bonomi. He learned that Ducati was in breach of loan covenants and would be facing bankruptcy soon and so decided to meet the CEO, Federico Minoli. During their meeting, Bonomi expected to discuss Ducati’s impending bankruptcy. Instead, Minoli focused on Ducati’s upcoming product placement in the new Batman movie. Bonomi thought:

“Here was the CEO of a company facing bankruptcy and he’s talking to me about celebrities and racing. Maybe there is a leadership problem in this company—this could be an opportunity.”

He decided to approach David Bonderman, the founder of TPG. As TPG was buying Investindustrial’s stake in another company, Bonomi had built a strong relationship with him and asked for exclusivity to evaluate Ducati for a possible acquisition. With no lawyers and bankers in the middle, TPG gave free access to Investindustrial. Being listed on the Milan exchange and controlled by a globally leading PE firm, Ducati’s books were surely in order. Exhibit 25.4 provides key financial figures for the 1996–2001 growth phase and, then, for the latest year 2005. From a preliminary financial inspection and by talking to management, Investindustrial realized the potential value of a deal. As Razzano commented:

EXHIBIT 25.4 DUCATI’S MILESTONES: OWNERSHIP AND KEY FIGURES

“We realized that since the fundamentals of the company were still strong, that with the right people, the least we could strive to do was to bring the performance back up to 2000–2001 levels. With a few changes, like refreshing the product lineup, the company could be able to lift back the EBIT margin from nothing to a double-digit percentage over a 4-to-5-year period. That should generate a decent return.”

As part of the strategic due diligence Investindustrial retained Porsche Consulting, the leading automotive manufacturing consulting firm in Europe, to prepare a comprehensive turnaround plan. This included revamping the customer acquisition model by repositioning the Ducati brand through premium models, as well as a detailed plan to improve efficiency in all areas (see Exhibits 25.5 and 25.6, respectively). The deal was completed shortly afterwards in March 2006 whereby a consortium led by Investindustrial acquired TPG’s remaining 30% stake for €74.5mn. The investment was made by Investindustrial Fund III (€38.7mn),3 where the rest of the funding was shared between one of its limited partners Hospitals of Ontario Pension Plan and another Italian private equity firm, BS Investimenti. Through this structure, Investindustrial obtained a controlling position in Ducati, which by Italian corporate law enabled it to nominate all but one of the directors on the board.

EXHIBIT 25.5 2005 DUE DILIGENCE: REVISING THE CUSTOMER ACQUISITION MODEL

EXHIBIT 25.6 2005 DUE DILIGENCE: STRONG POTENTIAL IMPROVEMENT IN ALL AREAS

Alongside €137mn of Ducati debt, the transaction represented an enterprise value (EV) of €306mn, 2.0 × of forecast 2006 sales, and 22.1 × of forecast 2006 EBITDA (24.8 × actual 2005 EBITDA). While this may seem a high entry valuation, Investindustrial did not perceive the current performance as indicative, as it expected to triple EBITDA within a few years. Paying off the entire debt and assuming a contraction of the entry multiple to 8.0 × EBITDA, Ducati would generate a 2.5 × return to investors.

IMPROVING THE COMPANY (2006–2008)

With the focus on operations instilled by the new owner and implementing the due diligence plan, Minoli managed to return the company to profitability. Revenue in 2007 jumped 30% over the previous year to €398mn, driven largely by the success of the new models (the 1098 and the Hypermotard) at higher price points. Actual unit sales grew from 35,095 in 2006 to 39,687 in 2007 to almost equal Ducati’s historical unit sales record achieved in 2001. Sales performance also reflected the strategic decision, taken in 2006, to lower inventory levels throughout the network which allowed fewer retail markdowns.

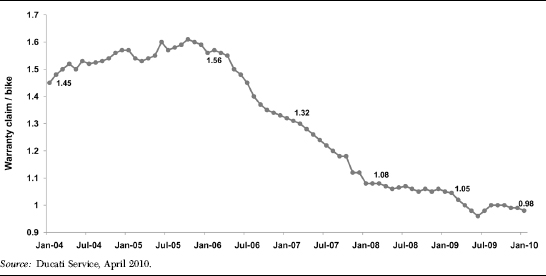

Previously, Ducati customers would have to wait 18 months to take delivery of the bike they ordered. By implementing the kaizen method popularized by Toyota, the lead time was reduced to a mere 40 days. These sweeping changes, along with the success of the new models in the marketplace, helped the company post consistent earnings over the period. The operational changes implemented to improve Ducati’s performance are summarized in Exhibit 25.7.

EXHIBIT 25.7A OPERATIONAL IMPROVEMENTS INITIATED BY INVESTINDUSTRIAL, 2006–2007

EXHIBIT 25.7B TREND OF WARRANTY CLAIMS PER BIKE, 2004–2010

As a result of a successful turnaround, Investindustrial understood that Ducati was ready for new management to take it forward to the next phase of growth. Minoli was replaced by Gabriele Del Torchio, who had years of experience working directly with a number of private equity houses—some spent as CEO of the global yacht manufacturer Ferretti. In August 2007, a recapitalization of the investment vehicle in Ducati generated a significant distribution to Investindustrial III, returning 118% of its investment in just 1.5 years.

THE WORLD MOTORCYCLE INDUSTRY IN 2008

The overall motorcycle market can be separated into bikes that are used as a primary means of transportation and bikes that are used for recreation. Almost all bikes with engines larger than 500,cc fall into the latter category. These recreational bikes can be broadly split into three subsegments—sport bikes, touring bikes, and cruisers. Sport bikes are aggressively styled motorcycles that closely resemble the features of a racing bike. The rider leans forwards into the wind improving aerodynamics, thus allowing higher speeds. Touring bikes are straightforward, versatile motorcycles where the rider sits upright or leans forward slightly. Cruisers emphasize comfort at the expense of performance. The rider sits at a lower seat height, leaning slightly backwards.

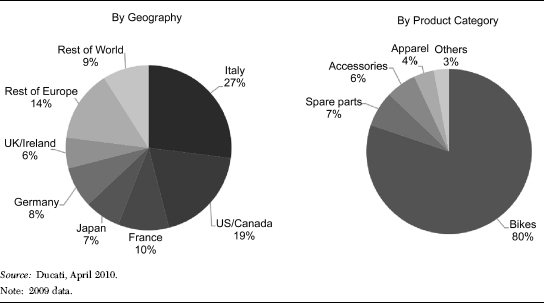

Worldwide sales of recreational bikes had reached an unprecedented high, primarily fueled by increasing discretionary income for a second or third vehicle. While Europe, North America, and Japan constituted the majority of sales, the importance of Asian and South American markets was increasing (see Exhibit 25.8 for a breakdown of Ducati’s sales by geography and product line). This worldwide demand was generally met by Japanese manufacturers—Suzuki, Honda, Yamaha, and Kawasaki—who dominated the market and produced the best-selling bikes in all categories. The sport bike segment was similarly dominated by Japanese manufacturers. Even in Europe, Japanese brands controlled over 70% of the sport bike market.

EXHIBIT 25.8 DUCATI TURNOVER BREAKDOWN

The Japanese manufacturers were the market leaders and catered products to the needs of the mainstream audience, with a focus on reliability and value for money. However, in each segment there were a few key niche players who defined the category and had a cult-like following. In the cruiser segment, that leader was Harley-Davidson which had built its reputation as the bike for the “wild child” in the 1960s and continued to occupy a strong place in the consciousness of the American consumer as a lifestyle product. The touring category was led by BMW which was able to apply the manufacturing principles of the automobile business to produce motorbikes that effectively balanced reliability and performance. Last, in the sport bike segment, the image leader and key niche manufacturer was Ducati, which translated technology developed by its racing subsidiary, Ducati Corse S.r.l., to produce models that captured the hearts and minds of motorcycle enthusiasts worldwide (see Exhibit 25.9 for market positioning and Exhibit 25.10 for Ducati Corse’s track record).

EXHIBIT 25.9A DUCATI MARKET SHARE

EXHIBIT 25.9B DUCATI’S STRATEGIC POSITIONING—FOCUSED NICHE BRAND

EXHIBIT 25.10 DUCATI’S RACING RECORD

RAISING A NEW FUND

By 2007 over 60% of the Investindustrial Fund III was invested and Bonomi was working closely with Mounir Guen, CEO of MVision, a leading global placement firm, to raise Investindustrial Fund IV. After spending 4 months on the road in Europe and the U.S., Investindustrial raised a record €1bn in 2008, twice the size of the previous fund. The strenuous process was over, as was uncertainty on Investindustrial’s ability to seal the target fund size. Now was the time to initiate a new of round of investments building on Investindustrial’s demonstrated accomplishment.

The new fund provided Investindustrial the capability of evaluating secondary investments in existing portfolio companies like Ducati where they held a minority stake.

A “WILD RIDE” FOR DUCATI’S STOCK

In November/December 2007, movements in Ducati’s stock price caused concern to Razzano. The stock lost half of its value only to quickly regain it and then lose it once again. Unprecedented volumes of stock were affected by fluctuations in value that were not in line with general movements in the Italian stock market or for comparable motorbike manufacturers worldwide. Razzano, a seasoned investment banker, suspected that this activity might be the result of a takeover attempt on Ducati—someone could be secretly buying enough of the company to emerge with a controlling stake.

Coincidentally, there was an indirect contact by a large player in the manufacturing sector who expressed interest in buying Investindustrial’s 30% stake in Ducati for a sizable premium. What started off as an exploratory conversation only a few weeks ago quickly escalated into real tangible interest. Given that Ducati had already returned Investindustrial investors their money, the extra return from an outright sale would deliver an excellent IRR.

Just a few months earlier, a number of bankers had also tried to persuade Investindustrial to take the company private. They were turned down since there were quite a few operational improvements under way and Investindustrial wanted to see them through before deciding to put any further money in. Since then, Gabriele Del Torchio, the new CEO, had done an excellent job in continuing the EBITDA growth, and Razzano felt more comfortable exploring this option. In line with a take-private practice, the bankers advised Investindustrial to offer a premium over the market price of €1.47 to ensure the success of the tender offer (see Exhibit 25.11 for Ducati’s key financial performance figures during the period and forecasts and Exhibit 25.12 for its balance sheet).

EXHIBIT 25.11 DUCATI’S KEY FINANCIAL PERFORMANCE AND FORECASTS (€ MILLION)

EXHIBIT 25.12 DUCATI: CONSOLIDATED BALANCE SHEET (DECEMBER 31, 2007)

Yet, at the same time the global stock market was tumbling on the back of the subprime crisis that had exploded in the U.S. several months prior. The equity market was taking a beating, with the S&P dropping 15% in just the previous 3 months. On Monday, January 21, 2008 oil prices broke the USD100-a-barrel psychological barrier for the first time. This caused a sharp drop in global equities triggered by concern that higher commodity prices would sharply impair corporate profits. With the FTSE 100 experiencing the biggest ever 1-day fall in points and European stocks closing with their worst results since September 11, 2001, some news headlines and general columnists termed it Black Monday and anticipated a global shares crash. Bonomi wondered if he should follow other private equity firms and hold off on transactions or continue to evaluate this deal on its own merit (see Exhibit 25.13 for 2008 macroeconomic parameters).

EXHIBIT 25.13 ITALIAN CAPITAL MARKET DATA

Following weeks of intensive research, Bonomi and Razzano felt they had sufficient information. They were in an enviable position where all options had strong merit. On one hand, Ducati could be exited to a trade buyer, thereby providing investors with an exceptional return. However, Investindustrial believed that Ducati had further growth potential and, thus, they might be leaving “money on the table” by exiting too early.

A second option would be to “double down” by taking the company private. They could take advantage of the market dip to acquire equity at relatively attractive valuations. The interest of a first-tier industry player to purchase the existing stake gave Investindustrial a credible reference point to determine how much to offer for the remaining 70% of the total 328 million outstanding shares. For a tender offer to succeed, it would require at least a ![]() 20 premium over the current €1.5 share price. To finance a possible tender offer, a short-term facility was secured from Banca Popolare di Milano and the Royal Bank of Scotland. Thereafter, Intesa Sanpaolo, leading a syndicate of Italian banks, would provide a permanent package consisting of €240mn senior debt and €35mn mezzanine (see Exhibit 25.14 for the terms). However, there were some issues they needed to address. Investindustrial, like other private equity firms, had limits on the amount it could invest from a fund in any single portfolio company. Depending on the price Bonomi had to pay to acquire the rest of Ducati, this could force him to concentrate close to 20% of the fund into just this investment. Also, since the capital would have to be drawn from the new fund, both Investindustrial III and Investindustrial IV would be investing in the company. Bonomi was worried that this might create an internal conflict of interest. A clear solution to this problem had to be presented to the investment committee before a follow-on investment could be authorized. The fact that a trade buyer had offered to buy Investindustrial’s stake in Ducati for a higher price than the proposed tender offer gave Investindustrial additional comfort and an arm’s length pricing benchmark.

20 premium over the current €1.5 share price. To finance a possible tender offer, a short-term facility was secured from Banca Popolare di Milano and the Royal Bank of Scotland. Thereafter, Intesa Sanpaolo, leading a syndicate of Italian banks, would provide a permanent package consisting of €240mn senior debt and €35mn mezzanine (see Exhibit 25.14 for the terms). However, there were some issues they needed to address. Investindustrial, like other private equity firms, had limits on the amount it could invest from a fund in any single portfolio company. Depending on the price Bonomi had to pay to acquire the rest of Ducati, this could force him to concentrate close to 20% of the fund into just this investment. Also, since the capital would have to be drawn from the new fund, both Investindustrial III and Investindustrial IV would be investing in the company. Bonomi was worried that this might create an internal conflict of interest. A clear solution to this problem had to be presented to the investment committee before a follow-on investment could be authorized. The fact that a trade buyer had offered to buy Investindustrial’s stake in Ducati for a higher price than the proposed tender offer gave Investindustrial additional comfort and an arm’s length pricing benchmark.

EXHIBIT 25.14 BANK DEBT PACKAGE FOR DUCATI’S TENDER OFFER (FEBRUARY 2008)

Third, there was the option of doing nothing. This could play out in an interesting way as, in the event of a hostile takeover, the acquirer might be ready to pay a significant premium to gain control of the company. However, this strategy also came with its own set of risks as there was no certainty that an acquirer would in fact materialize, and Investindustrial might lose the opportunity to either exit its investment or buy the remaining shares at a great price.

Bonomi had spent long days working with Razzano and the bankers to closely evaluate the financials behind each of the three options. As he headed home after a marathon working session, his phone rang. The strategic buyers interested in Ducati wanted to visit the Ducati plant in Bologna before making their formal bid for the Investindustrial consortium’s 30% stake in Ducati. He needed to think quickly in order to give them an answer.

JUNE 2010

Two years later, Bonomi wondered whether he had made the right decision in February 2008 when completing a public tender offer for Ducati in its entirety. At the time, the take-private had been at a much lower EV/EBITDA valuation than in the original entry, and the deal would make Investindustrial the most experienced public-to-private investor in the Italian market. Ducati had been one of four companies that Investindustrial had taken private for a combined enterprise value of €2.0bn. However, in the subsequent two years global financial markets had become profoundly jittery and in the process depressed consumption. Luxury good manufacturers were hit particularly hard. Many things that private equity had relied on were disappearing: loose credit fueling buoyant acquisitions had dried up and the IPO markets were firmly shut. In June 2010 the stability of financial markets was being tested again with Greece teetering on the brink of bankruptcy and analysts worrying about Ireland, Spain, Portugal, and Italy being next.

With €1bn of “dry powder” from its recent fund, the financial crisis felt like a perfect storm as the competition had difficulty in raising new capital. With the volume of activity in recent years, the Investindustrial team felt cohesive and experienced enough to face whatever new challenges presented themselves.

Bonomi picked up the phone to talk to Del Torchio about the sales of Ducati’s recently launched Multistrada model, an important step towards hopefully making “the Red One” from Borgo Panigale also a roaring investment success.

a This case was co-authored with Ashish Kumar, Norman Lee, and Vishal Radhakrishnan (LBS MBA 2010). Hans Holmen and Luca Simonazzi provided valuable comments.

1 This acquisition figure includes USD40mn of transaction costs.

2 Borgo Panigale is the suburb of Bologna where the Ducati factories are located.

3 Additional shares were purchased during 2007 thereby increasing Investindustrial Fund III’s investment to €41.3mn.