8 Conflict in close relationships

Abstract: A mountain of research focuses on how conflict interaction behaviors connect to relationship and individual factors (e.g., depression, health outcomes). We focus on how conflict behaviors connect to relationship satisfaction and stability. This chapter briefly and selectively represents this research: First, we frame our discussion in light of how cognitive processes limit people’s ability to discern conflict communication accurately. Second, we examine selected research on conflict in three close relationships: marital conflict, interparental conflict, and parent-child conflict. Finally, we present conclusions and implications regarding research on interpersonal conflict in close relationships.

Key Words: Marital conflict, interparental conflict, parent-child conflict, close relationships

1 Introduction

Twenty years have passed since Gottman’s (1994) influential book detailed how marital conflict predicts relational satisfaction and stability. Researchers continue to examine the role conflict plays in individual, marital, parent-child, and divorce outcomes (Canary and Canary 2013; Rhoades et al. 2012). The collective findings leave no doubt that communication constitutes the primary mechanism whereby people in close relationships manage conflict. As Heyman (2001: 6) stated, “Unifying the chaos [in research on relational dysfunction] is this simple fact: Couple communication is the common pathway across theories, therapies, therapists, and clients.” Both negative message behaviors and (often) positive communication affect and reflect relational quality and stability. For example, Graber et al. (2011) found that distressed couples are more likely than non-distressed couples to begin conflict interactions negatively and sustain that negativity throughout their interactions. And many theoretic models have been offered to explain how conflict combines with other variables to affect relational outcomes (e.g., Grych and Fincham 1990). These developments represent a new generation of conflict research. Also, recent models have emphasized how perceptions of conflict and actual interaction behaviors combine to affect individual as well as relational outcomes.

This chapter concerns the role that conflict plays in building or dismantling relational quality and stability. We divide our review into three major sections: (1) factors that influence the interpretation of conflict messages; (2) what constitutes conflict management communication; and (3) how conflict communication affects close relationships (i.e., marital, parent-child, and post-divorce relationships). Across various sections in this chapter, several themes emerge (e.g., interpretations of conflict carry biases that distort meaning of actual messages).

2 Cognitive processes and conflict

As a beginning point, we should note that several cognitions connect to conflict behavior (for a more extensive review, see Roloff and Miller 2006). Roloff and Miller analyzed five forms of social knowledge. For example, they examined how irrational beliefs lead to more negative conflict behavior. Irrational beliefs concern how one’s partner should be able to read one’s mind, sex should be perfect, sex differences are absolute, and so forth (see Eidelson and Epstein 1982, for others). Gaelick et al. (1985) found that holding irrational beliefs highly correlates with hostility during conflict interaction. In this section, we indicate what we view as the primary perceptual factors that work to interpret conflict management behaviors (see also Canary and Lakey 2013).

2.1 Myths surrounding understanding

First, people often rely on naive assumptions about the role of communication, understanding, and conflict. Sillars et al. (2005) exposed two assumptions: (1) understanding should induce communication that is responsive to individual and relational needs, and (2) marital and family members should engage in frequent, open, and direct communication. However, understanding has few consequences and conflict entails illusions that can promote or demote relational satisfaction. Also, both positive and negative associations can exist between understanding and marital satisfaction (Sillars et al. 2005: 106–107). As Sillars et al. (2005: 108) concluded, “understanding about conflict or discontent in a relationship might be a distinct phenomenon that does not follow baseline assumptions.”

Second, one cannot possibly attend to all the stimuli that occur during conflict. Berscheid and Regan (2005) reported that people can sense approximately 7,000,000 bites of information each second but can only attend to 10 or fewer bites of information per second. It follows that people must engage in very selective perception, simply because they cannot possibly attend to the stimuli at play during conflict. Given that conflict interactions are unstructured, goal changing, and self-serving, people can attend to and recall only a fraction of such interactions (Sillars and Weisberg 1987). For example, when people view their conflicts on videotape immediately following their interactions, recollections and interpretations of ones’ messages overlap only slightly with their partners’ recollections and interpretations (only 1% to 3%; Sillars et al. 2000). Moreover, the differential effects due to messages can vary between partners. For instance, Gaelic et al. (1985) reported that when men decrease their hostility, women interpret such decreases in hostility as love; this finding did not hold for women’s hostility.

One explanation for the near zero correlations in partners’ perceptions of each other concern how people mostly attend to their partner’s behavior, whereas they cannot attend much to their own behaviors. Storms (1973) explained that one’s field of vision focuses on external stimuli (i.e. partner behavior), yet peoples’ field of experience resides in their internal reactions (e.g., physiological changes, such as increased blood pressure). In this light, the partner’s behavior constitutes one’s external field of vision, and they can be literally seen as causing one’s own field of experience. At the same time, people’s own conflict behaviors do not affect their field of vision because they are invisible to self. The irony here concerns how one’s partner makes the same mistake of explaining the conflict in terms of one’s behavior within their field of experience.

Reaching understanding with one’s partner might increase if at least one person possess empathic accuracy, or the individual’s ability to infer correctly the other person’s thoughts and feelings, and assumed similarity, or the extent to which one’s rating of the partner coincides with how one feels the same emotion (Papp et al. 2010). Papp et al. found that wives and husbands infer the partner’s emotion through the use of behavioral cues from both self and other. However, Sillars et al. (2005: 123) found no direct correspondence with thoughts attributed to a family member; “they seem to have very little specific idea what others are thinking at a given moment during conversation.” Other researchers have investigated perceived empathic accuracy, which references perceptions of partners’ empathic accuracy and perceptions of understanding one’s partner (e.g., “I really understood my partner’s perspective”) (Bates and Samp 2011: 211). Bates and Samp found support for the general hypotheses that perceived empathic accuracy positively connects to resolution of conflicts. However, this research is constrained by how perceptions are compared instead of observational analysis tied to perceptions of the same event.

2.2 Attribution Dimensions

Next, and related to the point above, people can engage in negative attributions when explaining the cause of their conflicts. More precisely, negative attributions during conflict involve the dimensions of internality versus externality, stability versus instability, and globality versus specificity (Bradbury and Fincham 1990). In a word, dissatisfied couples rely on internal properties of the partner (e.g., the partner is selfish) that are stable over time (e.g., s/he drives recklessly, frightening others in the car) and global (e.g., selfishness explains his laziness, over-spending the family budget, and why he never does the laundry). Satisfied partners tend to rely on explanations that are external to the partner (e.g., the IRS just took all of his savings), unstable features of the conflict (e.g., he only drives fast when he is late), and specific to the conflict (e.g., he is angry only when paying the bills).

As one might anticipate, attributions for the cause of the conflict(s) affect one’s own reaction. That is, one’s explanation for the conflict directly affects one’s own behavior first, which behaviors in turn are perceived and explained by the partner using similar attribution dimensions. Sillars (1980) investigated the attribution dimensions that roommates made of each other and how these attributions associate with communication behaviors. When participants attributed more responsibility to their roommates, they perceived the cause of conflict as stable, were less likely to use integrative conflict strategies, and frequently relied on competitive conflict tactics. Roommates tended to use integrative strategies when they attributed cooperation to the other person and more responsibility of the conflict to themselves. Moreover, roommates reciprocated their conflict behaviors.

2.3 Emotion

Finally, conflict involves emotion. Indeed, some scholars view emotions/affect as the most valuable phenomenon when examining conflict in close relationships (Graber et al. 2011). Guerrero and La Valley’s (2006) review revealed that four particular emotions – anger, jealousy, hurt, and guilt – often emerge during conflicts. For instance, people experience hurt primarily as attacks on one’s relational or personal identity. Examples of hurtful messages involve behaviors such as verbal attacks or insults, describing the other’s behavior as a consequence of that person’s faults, evaluating the other person in demeaning ways, showing contempt, and so forth (Gottman 1994; Guerrero et al. 2006; Vangelisti and Young 2000). Moreover, it appears likely that discussion partners in research studies bring both positive and negative sentiment override (Heyman 2001). That is, the valence and intensity from previous contextual emotions at least partially shape how partners perceive each other and the research task before them, an “event specific” emotion (Sanford 2012: 298). As Sanford argues, “Even though couples may sometimes try to conceal their emotions from each other, in a long term relationship, it may be difficult to keep an emotion hidden. Partners may be able to draw from their contextual knowledge gained over the history of their relationship to make inferences about what each other is likely feeling …” (p. 298). The point here is that sentiment override – both positive and negative – contaminates research on how specific emotions coincide with specific conflict messages.

3 Views on conflict

Researchers have defined conflict communication in many different ways (Putnam, 2006). Three types of conflict message forms appear to be these: conflict as negative events; conflict as positive versus negative behaviors; and conflict as strategic orientations. Perhaps the easiest way to operationalize conflict is to use the Braiker and Kelley (1979) measure that treats conflict as the mere frequency of disagreement. For example, Kamp Dush and Taylor (2012), Papp (2012), and others have been interested primarily in the frequency of negative conflicts. In a similar vein, one can examine characteristics of negative conflict. For instance, Fosco and Grych (2010) found that a combination of frequent, intense, and irrational conflicts between parents leads to children’s sense of threat, self-blame, and inability to cope with the parent’s conflicts. Additionally, researchers have prioritized negative conflict tactics over positive tactics. These negative behaviors include Gottman’s “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse”: criticism/complaint, disgust, defensiveness, and stonewalling. Ridley, Wilheim, and Surra (2001) examined aggression (e.g., insult partner, threaten), and withdraw (e.g., hide tensions, leave room). Also, Du Rocher-Schudlich, Papp, and Cummings (2004) looked at the negative behaviors of insults, physical aggression, defensiveness, withdrawal, showing depression, and so forth. Finally, Rhoades et al. (2012) assessed negative communication (e.g., accusations, criticisms), aggression (pushing, grabbing, etc.), and parental conflict (e.g., “I saw my parents arguing, “My parents nagged and complained to each other”). Such a focus on negative conflict behaviors presents only one indicator of partners’ relational climate, though such behaviors are intuitively grasped. Yet this focus does not provide insight with regard to how positive conflict behaviors might affect relational quality, stability, and other outcomes.

Other researchers have discriminated positive from negative communication messages. Although research shows that negative behaviors affect relational outcomes more than do positive behaviors, direct and cooperative messages are most functional most of the time. For instance, Birditt et al. (2010) found that the use of destructive tactics and exchanges involving withdrawal led to divorce, whereas constructive tactics reduced the likelihood of divorce over a 16-year period. Focusing on the positive side, Carroll et al. (2013) used three positive tactics: self-soothing, which means calming oneself during an argument; empathy, or understanding one’s partner; and clear sending, or the ability to express oneself. Also, Ackerman, et al. (2011) argued that positive engagement includes factors of attentiveness, warmth, cooperation, and clarity. Naturally, alternative categories of positive conflict behaviors exist.

Finally, many scholars show interest in identifying how communication tactics cluster according to their strategic orientations. Conflict strategies refer to people’s approaches to manage conflict, and these approaches include a broad array of tactics that institute strategies (Ridley et al. 2001). In a review of conflict strategies and tactics, Sillars and Canary (2013) divided conflict tactics into four strategic orientations by cataloging observational research and using van de Vliert and Euwema’s (1994) typology as an organizational schema. The first strategy is Negotiation, which entails direct and face-honoring tactics. Negotiation tactics include accepting responsibility, engaging in problem solving/information exchange, proposing change, attempting reconciliation, using conciliatory acts, and the like. Direct Fighting, the second strategy, includes direct and face attacking behaviors such as blaming the partner, confrontative acts, denying validity of other’s argument, engaging in negative mindreading, using interruption, and the like. Nonconfrontation tactics represent indirect and face honoring tactics, which include changing the topic, denying a problem exists, trying off topic statements, using topic shifts, attempting topic avoidance, et cetera. Finally, Indirect Fighting involves denial of responsibility (for the conflict), showing dysphoric affect, providing excuses for self, and engaging in withdrawal. Sillars and Canary also identified several conflict tactics that convey two or more strategic orientations and interpretations, which they called polysemous. For instance, expressing feeling about a problem can be taken as honest disclosure, an accusation, or even a purposeful hurtful message.

4 Marital Conflict

4.1 Types of marriage

At this point, we begin our discussion regarding the role of conflict in different close relationships. Naturally, not all family norms are the same and they yield alternative “relational standards” that social actors adopt to understand what occurs during conflict and to guide their interactions (Sillars and Canary 2013).

How communication varies according to relational types probably begins with Fitzpatrick (1988), who derived three “pure” couple types – the Traditional, the Separate, and the Independent. Both partners must accede to one of these types or else they are “mixed.” Which type garners the most couples varies from sample to sample. Gottman (1994) observed that three types of functional marriages he discovered correspond remarkably with Fitpatrick’s three pure types. He offered the following equations: traditional = validating; independent = volatile; and separate = avoider. The point here is twofold: (1) Gottman found relational types that differentially interact during conflict in ways that conform to Fitzpatrick’s couple types; and (2) all three types of relationships are viable, satisfactory, and stable (Gottman 1994). That is, one’s relational standard for marriage can take different forms and be satisfying with a partner who shares the same relational standard. For instance, Kamp Dush and Taylor (2012) reported that validators (54% of their sample) expressed high happiness but moderate conflict. They were less likely to dissolve. Of course, other relational standards exist that affect choices of appropriate conflict behavior (Fitzpatrick, 1988).

For instance, Koerner and Fitzpatrick (2002, 2006; see also Zhang 2007; Chapter 18, Koerner) applied the notion of different relational schemata to families. Schemata can reflect one’s implicit beliefs regarding how relationships should be, and Koerner and Fitzpatrick’s research reveals that schemata affect how members from different family types communicate. For example, people from conversation-oriented families tend to prioritize frequent and expressive communication, and they employ direct conflict styles. When high conversation orientation is combined with low conformity (i.e., the pluralistic family type), the finding of frequent and open communication holds true. Other family members engage in more indirect, avoidant behaviors, such as in conformity oriented families (Koerner and Fitzpatrick 2002). Schrodt (2005) found that expressiveness was the most predictive factor of family cohesiveness and adaptability (vs. structural traditionalism and avoidance), reflecting the U.S. emphasis on being open and direct.

4.2 Conflict sequences: Demand-withdraw pattern

Importantly, conflict sequences differentiate satisfied from dissatisfied couples. Negative sequences include agreement–disagreement, proposal–counterproposal, attack–defend, demand-withdraw, and others. Positive sequences include validation, contracting, and supportiveness–supportiveness (e.g., Ting-Toomey 1983). The demand-withdraw pattern has received the lion’s share of recent research (Caughlin and Vangelisti 2006; see Chapter 19, Segrin and Flora). In this pattern, one person (typically the wife) attempts to approach the partner (the husband) about some issue, perhaps even through nagging and complaining, and that partner denies a problem exists, through avoidance, denial of any problem, refusal to discuss it, and so forth (Caughlin and Vangelisti 2006; Christensen and Heavy 1990). The demand-withdraw pattern has been consistently found to be detrimental to marital satisfaction (Birditt et al. 2010). However, Siffert and Schwartz (2011) reported that individual behavior was more predictive of subjective well-being than was demand-withdraw patterns between partners.

There are several explanations for the demand-withdraw pattern (Caughlin and Vangelisti 2006). Women tend to demand more than men; yet whoever wants change in the partner tends to demand more. First, the escape conditioning model holds that women are more likely to demand and men to withdraw because men want to leave the situation. Men are more sensitive to their physiological reactions, so they more likely want to leave the situation. Meanwhile, women tend to ignore their physiological changes and continue the pursuit of change. Second, the social structure model stresses how sex differences in demand/withdraw occur because women often lack the power that men enjoy. Because they are inequitably treated, women often demand change to obtain a balance of power and equity. Third, the conflict structure model holds that the person seeking change (the requestor) more likely continues the conflict; whereas, the person who is the target of change (the requestee) tends to withdraw. Finally, the individual difference model (Caughlin and Vangelisti 2000) holds that individual differences affect who demands as well as who withdraws. Accordingly, personality factors can predict the demand-with-draw pattern. For example, argumentativeness, conflict locus of control, and neuroticism are tied to the demand-withdraw pattern.

One critical issue regarding the demand-withdraw pattern concerns how very different behaviors constitute demand and withdraw. For many people, demand-withdraw involves behaviors that intuitively present what is meant by demand-withdraw. For example, Eldridge et al. (2007: 218) defined this pattern as “… one member (the demander) criticizes, nags, and makes demands of the other, while the partner (the withdrawer) avoids confrontation, withdraws, and becomes silent.” Such definitions narrowly describe what constitutes demand and withdraw and, accordingly, operationalize this pattern in intuitive and uniform ways (e.g., Caughlin and Vangelisti 2000: 555). Perhaps the most widely used measure of demand-withdraw is Christensen and Sullaway’s (1984). Their three items that measure demand-withdraw contain the following: “Woman [Man] tries to start a discussion while [Woman] Man tries to avoid a discussion;” “Woman [Man] nags and demands while [Woman] Man withdraws, becomes silent, or refuses to discuss the matter further;” and “Woman [Man] criticizes while Man [Woman] defends him/herself.” We believe that these items clearly represent demand-withdraw tactics and possess face validity and predictive validity, whereas more broadly defined operationalizations do not focus exclusively on demand-withdraw tactics.

For instance, Papp et al. (2009) defined demanding behavior using two subcategories of pursuit and personal insult. Pursuit refers to not relinquishing the issue or allowing the other person to leave the scene. Personal insult refers to direct and negative tactics, including making accusations, insulting the partner, blaming, rejecting, and use of sarcasm. Additonally, Papp et al. (2009: 291) defined withdraw behavior using three subcategories. First, defensiveness involves escaping blame, refusing responsibility, and offering excuses for one’s behavior, reacting to criticism with criticism, and so forth. Second, change topic refers to “changing the topic to avoid the interaction.” Finally, withdraw involves attempts to create distance from the interaction partner; these include stonewalling, leaving the scene, avoiding eye contact, and so forth. In brief, some demanding as well as some withdrawing behaviors often include a wide range of negative and positive behaviors that do not necessarily represent what most people think when discussing the demand-withdraw pattern. Accordingly, one cannot be certain that these behaviors actually refer to other positive and negative conflict patterns rather than the demand-withdraw pattern (e.g., attack-defend, Ting-Toomey 1983).

4.3 Ratios of positive and negative behaviors

Recently, several authors have examined positive/negative ratios of conflict communication. Perhaps the most recognized is Gottman’s (1994) work (see also Chapter 19, Segrin and Flora). According to Gottman, stable couples use five positive, constructive actions for every negative communication tactic, whereas unstable couples use slightly less than one positive/negative communication tactics. Leggett et al. (2012) found that positive/negative behaviors, in addition to cooperative conflict behaviors, accounted for up to 39% of the variance in marital satisfaction. Also, for dissatisfied couples, an increase occurs in the relative percentage of negative emotions over the course of conflict conversations (Gottman, 1994; Billings, 1979). The proportion of negative tactics among unhappy couples dramatically increases such that approximately 50% of the conflict interaction comprises negative emotions, reaching a 1 : 1 ratio of positive/negative tactics. However, satisfied couples do not escalate the relative proportion of negative tactics, and such couples’ conflict contain only 20% of negative conflict messages; so their ratios of positive to negative behaviors remains at 5 : 1.

At least three reasons explain the increased difference between satisfied and dissatisfied married couples in their ratios of positive/negative behavior. First, Gottman explained that these ratios reflect how couples balance each type of relationship. That is, partners engage in conflict behaviors that define the couple. In this manner, satisfied and stable couples balance every negative comment with five positive ones; dissatisfied and unstable couples balance every negative comment with one positive tactic. Second is that marital partners reciprocate behaviors, both positive and negative, which can escalate in a negative manner for dissatisfied couples more so than satisfied couples (Gottman, 1994). Gaelick et al. (1985) found that although partners attempt to reciprocate their partner’s emotions, they did so only for hostility and not love. Gaelick found that hostility increases over time, whereas statements involving love did not. A third reason concerns how interaction behaviors are largely scripted (Roloff & Miller, 2006). As dissatisfied partners begin their conversational exercise, they attempt to display courteous behavior. Once dissatisfied marital partners finish initial politeness, their typical and scripted conflict behaviors emerge regardless of the study’s procedures. People can only act the way they normally act; they know no other way to behave toward their partner. That is, married partners cannot adopt different cognitions of their partner, nor can they create new identities or roles after a few minutes of conflict conversation.

4.4 The punctuation problem

At this juncture, we discuss the “punctuation problem” (Watzlawick, Beavin, and Jackson 1967). Watzlawick et al. noted that people attempt to make sense to themselves and others by determining who is responding to whom. People need coherence and structure, but the lack of coherence and structure during conflict leads people to engage in irrational ways (Sillars and Weisberg 1987). The punctuation problem can be witnessed in negative reciprocation of conflict tactics that typically blame the other person for causing the conflict. Consider the example below, which illustrates the punctuation problem.

| Turn | Speaker | Message |

| 153 | M | I’m not mad about last night, I just want you to accept the fact that some, a lot of it was your fault and say “I’m sorry.” That’s all I want to hear. And for you to mean it, and say it won’t happen again, next time you say “I’m sorry;” it’s so hard for you to say. That’s all I want you to say is, “I’m sorry, it was my fault.” |

| 154 | F | Well, it wasn’t my fault. (Laughs) |

| 155 | M | How was it not your fault is what I’m saying? |

| 156 | F | Dave, I’m trying to tell you I came in last night and it was not my fault. I came in, expecting you to say, “Hi, honey”; you don’t say dirt to me for fifteen minutes and all of the sudden … |

| 157 | M | It was like five minutes, if that, and I was watching a game. Just like if you we’re watching a sad movie and I come in. |

| 158 | F | So what Dave? You always greet me. |

| 159 | M | So, so if I didn’t greet you maybe you should have seen that something was wrong with me. |

| 160 | F | I was too pissed off at my own little world to care about yours. |

| 161 | M | Exactly. |

| 162 | F | So what? |

| 163 | M | So what? So I was pissed off in my own world. |

| 164 | F | So that made us pissed off at each other. So it’s really nobody’s fault, is that what you’re trying to say? |

| 165 | M | No. |

| 166 | F | No you still think it’s my fault. God forbid (sarcastically). Let it go at that. |

| 167 | M | Because it always just goes at that. All I want you to say is “I’m sorry dude.” |

| 168 | F | I’m not saying “I’m sorry” because I didn’t … |

| 169 | M | Because you feel no fault, right? |

| 170 | F | Right. Right, I was upset. |

| 171 | M | So you’re blowing up at me tremendously … |

| 172 | F | So were you, tremendously yelling at me … |

| 173 | M | I NEVER YELLED AT YOU! |

This charged exchange of blame between partners reveals the punctuation problem this couple finds hard to escape. It also indicates one way that rational discussion deteriorates and partners appear to state whatever comes to mind in the heat of the moment – for instance, turns 156–165. Finally, this sequence illustrates how both partners can deny any responsibility for the conflicts. The following section reveals how such conflict between partners affects their children.

5 Interparental conflict

Interparental conflict constitutes a separate line of research from marital conflict. Although many parents are married to each other, and likely engage in marital conflict, studies of interparental conflict focus on the effects that interparental conflict have on children. This body of research contributes to conceptualizing conflict as a cross-relationship phenomenon that variously affects different relational partners. Scholars have emphasized four important processes regarding interparental conflict: transmission effects, spillover effects, triangulation, and appraisals (see Canary & Canary 2013 for more elaboration of this material).

5.1 Transmission effects

One line of interparental conflict research investigates how children learn conflict behaviors by watching their parents engage in conflict. This is known as a transmission effect. For example, Crockenberg and Langrock (2001) found that six-year-olds mimicked the behaviors of their same-sexed parents. Van Doorn, Branje, and Meeus (2007) also tested the transmission hypothesis. Results of that study support the transmission hypothesis for certain conflict behaviors, specifically in finding that conflict engagement (e.g., “getting furious and losing my temper”) and problem-solving (e.g., “compromising and discussion”) led to differences in parent-adolescent engagement and problem-solving two years later. Moreover, Cue et al. (2008) found that young adults’ relational quality depends on their conflict behaviors, which were previously influenced by their parents’ conflict behaviors. In a longitudinal study, Miga, Gdula, and Allen (2012) examined how parental conflict behaviors associate with children’s peer and romantic relationship negotiation and their romantic relationship quality from early adolescence to young adulthood. Results indicated that interparental reasoning when the adolescent was 13-years old affected the adolescent’s behaviors with close peers a year later. Also, interparental reasoning was associated five years later with adolescents relying less on autonomy/undermining behaviors with romantic partners (Miga et al. 2012: 452). Moreover, reasoning during interparental conflict episodes positively associated with positive romantic relationship quality in early adulthood. Although the focus of much interperental conflict research emphasizes the transmission of negative behaviors to parent-child and other relationships, research clearly points to positive benefits of transmission effects when adaptive tactics and strategies are used.

5.2 Spillover effects

Krishnakumar and Buehler (2000) defined spillover as “emotions, affect, and mood generated in the marital realm [that] transfers to the parent-child relationship” (p. 26). Spillover of conflict also refers to parents transferring their own marital conflict tactics to conflicts with their adolescents. According to O’Donnell et al. (2010: 13), “the core tenet of the spillover hypothesis is that the emotional distress and distractions of interperental conflict drain parental resources and make it less likely that parents will provide children with warmth, support, and structure, which in turn negatively impacts children’s emotional well-being.” As one might expect, negative emotions in marital interactions correspond with negative behaviors in the parent-child relationship (Crockenberg and Langrock 2001; Krishnakumar and Buehler 2000). Two common conflict spillover parental behavior tactics appear especially corrosive: increased harshness/aggressiveness and lack of involvement/responsiveness (Webster-Stratton and Hammond 1999). For instance, Fosco and Grych (2010) found that negative interperental conflicts reduced the amount of closeness and increased conflicts between children and parents. However, the converse of this hypothesis is that one can provide warm, involved, and responsive parenting, which in turn buffers the effects of interparental conflict (DeBoard-Lucas et al. 2010).

Negative spillover from interperental conflict coincides with child adjustment problems. For example, Buehler and Gerard (2002: 88) found that childhood maladjustment occurred as a result of parental spillover of negative conflict in terms of harsh parental discipline and lack of parental involvement. Negative interperental conflict also coincides with children’s perceptions of having negative relationships with their parents (Osborne and Fincham 1996) and children’s perceptions that their parents are unavailable (Clark and Phares 2004). Such perceptions of parental negativity and unavailability associate with child adjustment problems (e.g., internalizing and externalizing problems; Benson, Buehler, and Gerard 2008; Webster-Stratton and Hammond 1999).

5.3 Triangulation

Triangulation concerns an interaction pattern in which a child becomes involved in the parents’ conflict, either as a go-between or by feeling pressured to take one parent’s side in the conflict (Grych, Raynor, and Fosco 2004). In most cases, triangulation reflects a lack of appropriate boundaries between the parent’s role and the child’s role, which can lead to child confusion and dismay (Grych et al. 2004; Robin and Foster 1989). For example, mothers might be better able to conscript their children’s help during chronic negative conflicts, whereas fathers might minimize the nature of those same conflicts. Approximately one-third of children (mostly girls) are occasionally caught in the middle between their parents in conflict (Amato and Afifi 2006; Buchanan et al. 1991). Triangulation is experienced more often by children whose parents engage in negative, competitive conflict than by children whose parents engage in cooperative conflict interactions (Amato and Afifi 2006; Buchanan, Maccoby, and Dornbasch 1991; Grych et al. 2004). The focus of this research remains clearly on negative conflict communication. The focus concerns partners’ frequent, intense, and irrational conflict behaviors. We should underscore that these are the most studied features of conflict communication in the interparental conflict literature. Note that a focus on negative conflict limits our understanding of the role of positive and even perhaps avoidant communication strategies during triangulation.

Triangulation affects children’s internal and external adjustment. For example, Grych et al. (2004) found that triangulation explained the effects of interparental conflict on adolescents’ adjustment. They found that triangulation itself led to both internalizing (e.g., withdrawal) and externalizing (e.g., aggression) problems in adolescents. Also, Buchanan et al. (1991) found that triangulation mediated the effects of interparental conflict on adolescent depression and deviance, which represent internalizing and externalizing problems. Importantly, children tend to blame themselves for their parent’s conflict especially if the children are triangulated (Fosco and Grych 2010; Grych and Fincham, 2001). Additionally, Grych et al. (2004) found that the closeness of the family served a protective function against triangulation.

5.4 Appraisals and emotional security

An important concept for understanding transmission, spillover, and triangulation concerns how children make sense of interparental conflict, or their appraisals. Appraisals refer to evaluations of whether and how particular events relate to one’s well-being (Maguire, 2012: 52). For children and interparental conflict, two appraisals become especially important – threat and self-blame (e.g., Fosco and Grych 2007, 2010; Grych et al. 2004). Threat refers to the extent that the child fears the possible outcomes of interparental conflict for them, for example, the parent-child relationship is in jeopardy, the interparental conflict will escalate, one parent might leave the scene, and other concerns. Self-blame refers to the extent that the child feels responsible for interparental conflict; that is, the child believes that the conflict occurs because of him/her. The more children believe that their parents’ conflicts threaten their well-being and are their fault (“Please … I’ll be better.”), the more interparental conflicts will be salient and affect the children negatively. Research indicates that negative and competitive interparental conflict leads to appraisals of threat and self-blame (e.g., Grych et al. 2004). In particular, the more frequent, intense, and irrational the conflicts, the more likely they negatively affect appraisals. For example, Fosco and Grych (2010) found that intense and poorly managed conflicts increase the child’s sense of threat, self-blame, and inability to cope with the parent’s conflicts (for a fuller treatment of this topic, see Grych and Finchman, 2001).

The emotional security theory offers insight into interparental conflict processes (Cummings and Davies 2010). The emotional security hypothesis “posits that preserving and promoting [children’s] own sense of emotional security is a primary goal that motivates children’s actions and reactions” (Davies and Cummings 1998: 125). Also, the child’s sense of emotional security mediates the connection between interparental conflict and childhood adjustment (Davies and Cummings 1998). That is, the fear, resentment, threat, and self-blame that often accompany interparental conflict depend on whether or not the child feels safe. A combination of destructive conflict and insecurity lead to two problems in the parent-child relationship. The first problem concerns parenting difficulties, such as decreases in warmth, involvement, and acceptance. The second problem concerns how destructive conflicts harm the married partners’ attachment systems. If married partners “learn” from their hostile conflicts not to trust others, to show warmth, or to support others, they are less likely to show their children positive models for how relationships work.

6 Parent-child conflict

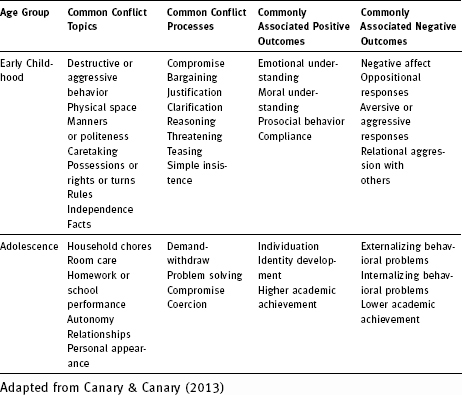

A critical relational context for interpersonal conflict research involves the parent-child relationship. Parent-child conflict influences, and is influenced by, other family experiences such as interparental conflict, child behavior, and parent-child relationship qualities (Burt et al. 2005; Ostrov and Bishop 2008). The bulk of parent-child conflict research concerns early childhood and adolescence; accordingly, we divide our discussion by age groups most representative of the research. The concentration on these age groups makes intuitive sense, considering the dramatic developmental changes children encounter during the toddler-preschool years and during adolescence. Table 1 summarizes research findings for early childhood and adolescent age groups. Although much research investigates topics regarding parents and children in conflict, our discussion focuses on research concerning conflict processes and outcomes.

6.1 Early childhood

Observational studies of mothers and young children reveal the importance of constructive conflict interaction. Laible and Thompson (2002) found that mothers’ use of conflict mitigating strategies, such as compromise and bargaining, and justification strategies, such as clarifications and reasoning, associate with several positive characteristics in toddlers six months after observations. These positive outcomes included children’s emotional understanding, sociomoral competence, and prosocial perceptions of relationships. However, maternal references to rules and consequences did not associate with similar positive socioemotional characteristics in their children. In a similar study, Huang et al. (2007) analyzed children’s reactions to mothers’ responses during mother-child conflicts. Mothers’ uses of constructive responses (e.g., distraction, reasoning, negotiating) and simple oppositional responses (saying “no”) positively associated with children’s adaptive responses (e.g., obeying or negotiating) but were negatively associated with children’s overt oppositional responses (e.g., saying “no,” throwing temper tantrums). Huang et al. reported that less favorable outcomes, such as unresolved conflicts between mothers and children, were associated with destructive maternal responses (e.g., criticisms, threatening).

6.2 Adolescence

During adolescence, children transition into adulthood that leads to a variety of contentious topics and processes. Research indicates that parent-child conflict frequency tends to be lower in early and late adolescence but peaks in mid-adolescence (Allison and Schultz 2004; Smetana et al. 2003). This inverted U pattern reflects developmental processes of children asserting their identies in a conflictual manner and then moving toward adulthood with less conflict. Interestingly, conflict intensity steadily increases throughout adolescence (Cicognani and Zani 2010; Flannery et al. 1993; Smetana et al. 2003). The increased intensity might be at least partially explained by different perceptions of conflict interactions held by teens and their parents. To investigate this idea, Sillars, Smith, and Koerner (2010) found that parents over-attributed negative thoughts to their adolescents, whereas adolescents over-attributed controlling thoughts to their parents (Sillars et al. 2010: 742).

Indications of the inverted U pattern of frequency and the linear increase in intensity across the adolescent age range have led researchers to differentiate early, mid, and late adolescence. These studies isolate one sub-group (e.g., Rinaldi and Howe 2003), compare sub-groups (Branje et al. 2009), or longitudinally follow participants from early adolescence to late adolescence (van Doorn et al. 2007). For example, Branje et al. (2009) found that older adolescents were more likely than younger adolescents to use positive conflict management strategies, such as trying to understand the other person, using reasoning, and searching for compromise. Younger adolescents were more likely than older adolescents to use negative strategies, such as attacking the other, being verbally abusive, or withdrawing. Also, younger adolescents were more likely than older adolescents to end interaction without resolving the conflict. The researchers also investigated how conflict strategies associated with internalizing behaviors (e.g., depression) and externalizing behaviors (e.g., delinquency) among participants. Early adolescents’ use of withdrawal in parent-child conflict associated with externalizing behaviors. Additionally, participants who combined multiple negative conflict management strategies, such as aggression, withdrawal, and exit without resolution, reported more internalizing problems. On a more positive note, adolescents who used effective conflict management strategies characterized by high levels of positive problem solving and low levels of the negative strategies experienced low to medium levels of conflict with their parents and lower levels of externalizing and internalizing adjustment problems.

Much of the parent-child conflict research relates to, or includes, interparental conflict research discussed earlier. These studies focus on transmission effects, spillover, or both. For example, Rinaldi and Howe (2003) studied marital conflict, sibling conflict, and parent-child conflict. Children recruited for their study were early adolescents. That study found that parent-child reasoning, verbal aggression, and avoidance conflict strategies were positively correlated with the same strategies in interparental conflict (Rinaldi and Howe 2003: 455). This study supports the spillover hypothesis with marital conflict interactions spilling into parent-child conflict interactions. In a similar manner, Van Doorn et al. (2007) investigated conflict across family sub-systems to determine whether explanations other than the spillover hypothesis might help inform how sub-systems influence family members over time. Van Doorn et al. (2007) found that parents’ use of positive problem solving and negative conflict engagement, but not withdrawal, positively associated with adolescents’ use of the same strategies in parent-child conflict two years later. However, bi-directionality of influence was not found, indicating that a stronger influence exists in conflict dynamics from parents to children than from children to parents.

Parent-adolescent conflict research has also focused on conflict strategies, tactics, and sequences. For example, Caughlin and Malis (2004) examined whether the demand-withdraw pattern emerges in parent-adolescent conflict. They examined how parent–demand/adolescent–withdraw associates with relationship satisfaction. Results revealed that the more participants reported the demand-withdraw pattern in their parent-child conflicts, the less they reported being satisfied with their parent-child relationships. These results comport with findings of marital conflict, indicating the pervasive negative effect this sequence can have across family subsystems. Cicognani and Zani (2010) also studied parent-adolescent conflict strategies and outcomes. Results of that study were encouraging, with participants reporting the use of compromise strategies more than aggressive strategies and reporting that their conflicts tended to end with more intimacy than frustration.

7 Conclusions and implications for future research

We conclude this chapter by discussing some challenges that the conflict research present. These sub-sections concern other domains of behavior, different definitions of conflict, positive outcomes of conflict, and inclusion of different relationships.

7.1 Other domains of behavior can complement conflict

Of course, conflict does not capture the entire nature of relationship processes. Several recent efforts to examine how conflict messages affect relational satisfaction and stability have included other types of behavior. Coupling conflict to another domain of behavior often increases the amount of variance accounted for in relational satisfaction and stability. The most commonly studied domain of behavior that complements conflict is supportiveness. Supportive messages and conflict messages often work independently to predict relational satisfaction (Pasch and Bradbury 1998; Sullivan et al. 2010). Supportiveness can limit the effects of negative conflict (Sullivan et al. 2010). Also, using more supportive than unsupportive behaviors assists people in their conflict management (Gottman and Levenson 1992; Sullivan et al. 2010). Lack of supportive behaviors, however, can increase negative emotions expressed during conflict. Stable and satisfied couples report higher levels of support and lower of levels of conflict than do their counterparts (Pasch and Bradbury 1998; Sullivan et al. 2010). Finally, high levels of conflict and low levels of support have consistently been linked negatively to individual well-being (Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton 2001).

This research presents strong evidence that researchers should consider the overall role conflict management has when predicting outcomes. The question is whether one should include other variables in conflict research and, if so, which factors theoretically operate in conjunction with conflict. This issue should be addressed by first examining the outcomes that one aims to explain. For example, research on conflict that attempts to explain indicators of relationship quality (e.g., satisfaction, commitment) would most likely benefit from including other behaviors that define relationships (e.g., social support, maintenance behaviors).

7.2 Conceptual and operational definitions vary

Second, alternative definitions and measures of conflict make synthesis very difficult. We do not claim that researchers should have similar conceptual or operational definitions. Rather, we argue that strong generalizations about the nature, function, and scope of conflict should acknowledge the wide range of behaviors that researchers call conflict. At a minimum, one cannot presume uniformity regarding what conflict is or how it functions. Moreover, theoretic and modeling approaches can affect how one makes use of conflict message. For instance, and as described above, definitions and operationalizations of the demand-withdraw pattern differ in terms of how narrow researchers conceptualize these behaviors. In a word, one cannot currently make strong generalizations about demand-withdraw behaviors. Similarly, scholars should reference their definitions of other conflict strategies and sequences.

Other method-based factors interleave the conflict communication literature. For example, differences in discussion task appear to affect conflict outcomes. Bates and Samp (2011) found that the type of discussion task affected whether conflict was resolved. A non-relational discussion was more often perceived as resolved, whereas a relational discussion task (e.g., disagreements regarding commitment) were more often perceived as unresolved. Moreover, the kinds of topics discussed can alter people’s use of communication. For example, Eldridge et al. (2007) examined demand-withdraw patterns in interactions about relationship versus individual issues. Eldridge et al. found that demand-withdraw behaviors occurred more when parties discussed relationship issues. Graber et al. (2011) argued that having participants engage in problem-solving interactions is not enough to predict marital quality. Rather, interactions regarding positive topics (i.e., “love task”) can buffer the effects due to negative conflict strategies. Still Graber et al. found that wife expression of contempt and affection during a conflict discussion each predicted the likelihood of divorce 16 months later. Clearly, the type of discussion task affects people’s communication behavior. The question becomes for conflict researchers whether they should provide topics for discussion that are largely unrelated to conflict issues (e.g., a love task).

7.3 Positive outcomes of conflict

Putnam (2006) observed that negative correlates of conflict abound in the research literature, devoting much less spaces to positive outcomes. We concur. Negative aspects of conflict in close relationships dominate research findings, for instance interparental research focuses almost exclusively on parents’ frequent, intense, and irrational behaviors. Thus, research on interparental conflict largely neglects how positive interparental conflict tactics might affect children’s triangulation and appraisals.

Other research points to ways in which positive conflict behaviors might lead to positive individual and relationship outcomes. For example, Ackerman et al. (2011) observed family conflict interactions over a three-year period to assess individual, relationship, and family-level variance in positive behaviors. That study found notable consistency over time in family members’ use of positive engagement behaviors in conflict, consisting of communicating ideas effectively and appropriately, being attentive and expressing interest in others’ messages, being cooperative and helpful, and assertively expressing opinions (Ackerman et al. 2011: 722). Ackerman et al. also found significant reciprocity effects in horizontal family relationships, indicating that mother-father pairs and sibling pairs reciprocate positive conflict strategies. Because family members’ conflict strategies largely remain stable, the development of family norms for positive interpersonal behaviors persists over time and is demonstrated in conflict interactions.

In addition to considering general family norms, several studies indicate that positive outcomes are related to interparental and parent-child conflict. For example, Van Doorn et al. (2007) found that parents’ strategies used in marital conflict, including positive problem solving, predicted adolescents’ use of similar strategies two years later. Similarly, studies of mother-toddler conflict interactions indicate that early parent-child conflict interactions can lead to positive behavioral and developmental outcomes in young children (e.g., Huang et al. 2007; Laible and Thompson 2002). These positive outcomes of conflict interaction behaviors, for whole families, specific relationships, and individuals deserve more empirical and theoretical attention.

7.4 Consideration of multiple relationships

Finally, recent research indicates the importance of considering multiple relationship influences in the complex process of conflict in close relationships. For example, Ackerman et al. (2011: 729) found significant effects of family norms for positive interpersonal behaviors in conflict interactions over a three-year period. Using a social relations model (SRM), they separated actor, partner, relationship, and family influences. They concluded that dyadic behavior is not always unique to the dyad. Several studies, reviewed in this chapter and elsewhere (Canary and Canary 2013), consider ways in which various dyadic family conflicts affect other members in the family. Future research should continue to consider conflict in multiple relationships within larger relational systems.

In addition to influences of multiple family relationships, some research has begun to investigate how conflict in close relationships is influenced by other understudied relationships. For example, Ehrlich, Dykas, and Cassidy (2012) found an important parent-adolescent conflict by friend-adolescent conflict interaction effect on adolescent social functioning. Only adolescents who experienced high conflict with their best friends and their parents displayed poor social functioning. Little research has explored such interaction effects and this appears to be a productive direction for future research.

To conclude, contemporary research shows that conflict communication continues to provide an abundance of information about how people interact with each other in ways that affect each other and their relationships. Advances in this research have provided new platforms from which researchers can launch further compelling work on this important domain of behavior.

References

Ackerman, Robert A., Deborah A. Kashy, M. Brent Donnellan and Rand D. Conger. 2011. Positive-engagement behaviors in observed family interactions: A social relations perspective. Journal of Family Psychology 25: 719–730.

Allison, Barbara N. and Jerelyn B. Schultz. 2004. Parent-adolescent conflict in early adolescence. Adolescence 39: 101–119.

Bates, Christina E. and Jennifer A. Samp. 2011. Examining the effects of planning and empathic accuracy on communication in relational and nonrelational conflict interactions. Communication Studies 62: 207–223.

Berscheid, Ellen and Pamela C. Regan. 2005. The psychology of interpersonal relationships. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall.

Birditt, Kira S., Edna Brown, Terri L. Orbuch and Jessica M. McIlvane. 2010. Marital conflict behaviors and implications for divorce over 16 years. Journal of Marriage and the Family 72: 1188–1204.

Bleil, Maria E., Jeanne M. McCaffery, Matthew F. Muldoon, Kim Sutton-Tyrrell and Stephen B. Manuck. 2004. Anger-related personality traits and carotid artery atherosclerosis in untreated hypertensive men. Psychosomatic Medicine 66: 633–639.

Bradbury, Thomas N. and Frank D. Fincham. 1990. Attributions in marriage: Review and critique. Psychological Bulletin 107: 3–33.

Braiker, Harriet. B. and Harold. H. Kelley. 1979. Conflict in the development of close relationships. In Burgess, Robert. L. and Ted L. Huston (Eds.), Social Exchange in Developing Relationships, 135–168. New York: Academic Press.

Branje, Susan J. T., Muriel van Doorn, M., Inge van der Valk and Wim Meeus. 2009. Parent-adolescent conflicts, conflict resolution types, and adolescent adjustment. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology 30: 195–204.

Burpee, Leslie C. and Ellen J. Langer. 2005. Mindfulness and Marital Satisfaction. Journal of Adult Development 12: 43–51.

Burt, S. Alexandra, Matt McGue, William G. Iacono and Robert F. Krueger. 2006. Differential parent-child relationships and adolescent externalizing symptoms: Cross-lagged analyses within monozygotic twin differences design. Developmental Psychology 42: 1289–1298.

Canary, Daniel J. and Sandra Lakey. 2013. Strategic Conflict. New York, NY: Routledge.

Canary, Heather E. and Daniel J. Canary. 2013. Family Conflict. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Carroll, Sarah June, E. Jeffrey Hill, Jeremy B. Yorgason, Jeffry H. Larson and Jonathan G. Sandberg. 2012. Couple communication as a mediator between work-family conflict and marital satisfaction. Contemporary Family Therapy: 1–16.

Caughlin, John P. and Rachel S. Malis. 2004. Demand/withdraw communication between parents and adolescents as a correlate of relational satisfaction. Communication Reports 17: 59–71.

Caughlin, John P. and Anita L. Vangelisti. 2000. An individual difference explanation of why married couples engage in demand/withdraw pattern of conflict. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17: 523–551.

Caughlin, John P. and Anita L. Vangelisti. 2006. Conflict in dating and marital relationships. In John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, 129–58. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Choi, Heejeong and Nadine F. Marks. 2008. Marital conflict, depressive symptoms, and functional impairment. Journal of Marriage and the Family 70: 377–390.

Cicognani, Elvira and Bruna Zani. 2010. Conflict styles and outcomes in families with adolescent children. Social Development 19: 427–436.

Christensen, Andrew and Megan Sullaway. 1984. Communication patterns questionnaire. Unpublished document. University of California, Los Angeles.

DeBoard-Lucas, Renee L., Gregory M. Fosco, Sarah R. Raynor and John H. Grych. 2010. Interparental conflict in context: Exploring relations between parenting processes and children’s conflict appraisals. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 39: 163–175.

Du Rocher-Schudlich, Tina D., Lauren M. Papp and E. Mark Cummings. 2004. Relations of husbands’ and wives’ dysphoria to marital conflict resolution strategies. Journal of Family Psychology 18: 171–183.

Ehrlich, Katherine B., Matthew J. Dykas and Jude Cassidy. 2012. Tipping points in adolescent adjustment: Predicting social functioning from adolescents’ conflict with parents and friends. Journal of Family Psychology 25: 77–783.

Eldridge, Kathleen, A., Mia Sevier, Janice Jones, David C. Atkins and Andrew Christensen. 2007. Demand-withdraw communication in severely distressed and nondistressed couples: Rigidity and polarity during relationship and personal problem discussions. Journal of Family Psychology 21: 218–236.

Eidelson, Roy J. and Norman Epstein. 1982. Cognition and relationship maladjustment: Development of a measure of dysfunctional relationship beliefs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 50: 715–720.

Flannery, Daniel J., Raymond Montemayor, Mary Eberly and Julie Torquati. 1993. Unraveling the ties that bind: Affective expression and perceived conflict in parent-adolescent interactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 10: 495–509.

Fosco, Gregory M. and John H. Grych. 2010. Adolescent triangulation into parental conflicts: Longitudinal implications for appraisals and adolescent-parent relations. Journal of Marriage and the Family 72: 254–266.

Gaelick, Lisa, Galen V. Bodenhausen and Robert S. Wyer. 1985. Emotional communication in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49: 1246–1265.

Gottman, John M. 1994. What Predicts Divorce? The Relationship Between Marital Processes and Marital Outcomes. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Graber, Elana, C., Jean-Philippe Laurenceau, Erin Miga, Joanna Chango and James Coan. 2011. Conflict and love: Predicting newlywed marital outcomes from two interaction contexts. Journal of Family Psychology 25: 541–550.

Guerrero, Laura K. and Angela G. La Valley. 2006. Conflict, emotion, and communication. In John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, 69–96. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Grych, John H. and Frank D. Fincham. 1990. Marital conflict and children’s adjustment: A cognitive-contextual framework. Psychological Bulletin 108: 267–90.

Grych, John H. and Frank D. Fincham. 2001. Interparental conflict and child development: Theory, research, and application. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Heyman, Richard E. 2001. Observation of couple conflicts: Clinical assessment applications, stubborn truths, and shaky foundations. Psychological Assessment 13: 5–35.

Huang, K.-Y., Teti, D. M., Caughy, M. O., Feldstein, S., & Genevro, J. 2007. Mother-child conflict interaction in the toddler years: Behavior patterns and correlates. Journal of Child & Family Studies 16: 219–241.

Kamp Dush, Claire M. and Miles G. Taylor. 2012. Trajectories of marital conflict across the life course: Predictors and interactions with marital happiness trajectories. Journal of Family Issues 33: 341–368.

Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K and Tamara L. Newton. 2001. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychological Bulletin 127: 472–503.

Koerner, Ascan. F. and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick. 2002. Toward a theory of family communication. Communication Theory 12: 70–91.

Koerner, Ascan F. and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick. 2006. Family conflict communication. In John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, 159–185. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Laible, Deborah J. and Ross A. Thompson. 2002. Mother-child conflict in the toddler years: Lessons in emotion, morality, and relationships. Child Development 73: 1187–1203.

Leggett, Debra G., Bridget Roberts-Pittman and Sara Bycek. 2012. Cooperation, conflict, and marital satisfaction: Bridging theory, research, and practice. The Journal of Individual Psychology 68: 182–199.

Miga, Erin M., Julie Ann Gdula and Joseph P. Allen. 2012. Fighting fair: Adaptive marital conflict strategies as predictors of future adolescent peer and romantic relationship quality. Social Development 21: 443–460.

Ostrov, Jamie M. and Christa M. Bishop. 2008. Preschoolers’ aggression and parent-child conflict: A multiinformant and multimethod study. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology 99: 309–322.

Papp, Lauren M. 2012. Longitudinal associations between parental and children’s depressive symptoms in the context of interparental relationship functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies 21: 199–207.

Papp, Lauren, M., Chrystyna D. Kouros and E. Mark Cummings. 2010. Emotions in marital conflict interactions: Empathic accuracy, assumed similarity, and the moderating context of depressive symptoms. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 27: 367–387.

Pasch, Lauri A. and Thomas N. Bradbury. 1998. Social support, conflict, and the development of marital dysfunction. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66: 219–230.

Putnam, Linda L. 2006. Definitions and approaches to conflict management. In John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, 1–32. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Rhoades, Galena K., Scott M. Stanley, Howard J. Markman and Erica P. Ragan. 2012. Parents’ marital status, conflict, and role modeling: Links with adult romantic relationship quality. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage 53: 348–367.

Ridley, Carl A., Wilheim, Mari S., & Surra, C. A. 2001. Married couples’ conflict reponses and marital quality. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 18: 517–534.

Rinaldi, Christina M. and Nina Howe. 2003. Perceptions of constructive and destructive conflict within and across family subsystems. Infant and Child Development 12: 441–459.

Roloff, Michael E. and Courtney Waite Miller. 2006. Social cognition approaches to understanding interpersonal conflict and communication. In John G. Oetzel and Stella Ting-Toomey (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Conflict Communication: Integrating Theory, Research, and Practice, 97–128. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sanford, Keith. 2012. The communication of emotion during conflict in married couples. Journal of Family Psychology 26: 297–307.

Schrodt, Paul. 2005. Family communication schemata and the circumplex model of family functioning. Western Journal of Communication 69: 359–376.

Siffert, Andrea and Beatrice Schwarz. 2011. Spouses’ demand and withdrawal during marital conflict in relation to their subjective well-being. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 28: 262–77.

Sillars, Alan L. 1980. Attributions and communication in roommate conflicts. Communication Monographs 47: 180–200.

Sillars, Alan L. and Daniel J. Canary. 2013. Conflict and relational quality in families. In Anita L. Vangelisti (Ed.), Handbook of Family Communication (2nd ed.), 338–357. New York, NY: Routledge.

Sillars, Alan L., Ascan Koerner and Mary Anne Fitzpatrick. 2005. Communication and understanding in parent-adolescent relationships. Human Communication Research 31: 102–128.

Sillars, Alan L., Linda J. Roberts, Kenneth E. Leonard and Tim Dun. 2000. Cognition during marital conflict: The relationship of thought and talk. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17: 479–502.

Sillars, A., Traci Smith and Ascan Koerner. 2010. Misattributions contributing to empathic (in)accuracy during parent-adolescent conflict discussions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 27: 727–747.

Sillars, Alan L. and Judith Weisberg. 1987. Conflict as a social skill. In Micahel E. Roloff & Gerald R. Miller (Eds.), Interpersonal Processes: New Directions in Communication Research, 140– 171. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Smetana, Judith G., Christopher Daddis and Susan S. Chuang. 2003. “Clean your room!” A longitudinal investigation of adolescent-parent conflict and conflict resolution in middle-class African American families. Journal of Adolescent Research 18: 631–650.

Storms, Michael D. 1973. Videotape and the attribution process: Reversing actors’ and observers’ points of view. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 27: 165–175.

Ting-Toomey, Stella. 1983. An analysis of verbal communication patterns in high and low marital adjustment groups. Human Communication Research 9: 306–319.

Van de Vliert, Evert and Martin C. Euwema. 1994. Agreeableness and activeness as components of conflict behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 66: 674–687.

Van Doorn, Muriel D., Susan J. T. Branje and Wim H. J. Meeus. 2007. Longitudinal transmission of conflict resolution styles from marital relationships to adolescent-parent relationships. Journal of Family Psychology 21: 426–434.

Vangelisti, Anita and Stacy L. Young. 2000. When words hurt: The effects of perceived intentionality on interpersonal relationships. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 17: 395–424.

Watzlawick, Paul, Janet Beavin and Don D. Jackson. 1967. Pragmatics of Human Communication: A Study of Interactional Patterns, Pathologies, and Paradoxes. New York, NY: Norton.