11 Imagined interactions

Abstract: Imagined interactions (IIs) are a mechanism underlying intrapersonal communication. In this chapter, I briefly review levels of communication based on a continuum of communication ranging from the most personal or individualistic to the most collectivistic or public, followed by definitions of intrapersonal communication. Intrapersonal communication is necessary, but not sufficient for all other types of communication to take place. Subsequently, a typology of intrapersonal communication definitions is presented which leads into imagined interaction theory. The theory provides a mechanism for measuring intrapersonal communication. The attributes and functions of IIs are presented. This discussion is followed by a case study revealing physiological indicators of intrapersonal communication in the form of heart-rate variability while a couple is imagining a conversation discussing pleasing and displeasing issues in their relationship. Cardiovascular studies involving road rage are also presented. The chapter concludes with using IIs to alleviate communication apprehension while giving speeches.

Key Words: imagined interaction, social cognition, physiology, daydreaming, imagery

1 Introduction

Intrapersonal communication is the foundation of all communication and can be viewed as a cognitive and thinking process within an individual (Honeycutt 2003, 2010a). The way that society communicates in our complex daily lives may only be understood after we are able to comprehend that communication utterly relies on our particular perceptions of the reality that surrounds us. Intrapersonal communication encompasses daydreaming, nocturnal lucid dreaming in the form of rapid eye movement and introspection and includes emotions ranging from sadness to joy, including thoughts internal to the communicator. Over 60 years ago in their classic book Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry, Ruesch and Bateson (1951) argued that intrapersonal communication is indeed a special case of interpersonal communication, as internal dialogue is the foundation for all discourse.

Imagined interactions (IIs) allows the study of social cognition and communication. While definitions of intrapersonal communication vary and cover a number of facets including its operations and properties, they center on mentalist operations and cognitive processes (Cunningham 1989).

2 Imagined interactions defined

Imagined interactions (IIs) are a type of daydreaming and social cognition involving mental imagery that is theoretically grounded in symbolic interactionism and script theory in which individuals imagine conversations with significant others for a variety of purposes (Honeycutt 2003). Honeycutt and Bryan (2011) discuss how scripts are a type of automatic pilot providing guidelines on how to act when one encounters new situations. Scripts are activated mindlessly and created through IIs as people envision contingency plans for actions.

The term “imagined interaction” is strategically used instead of “imaginary conversation” or “internal dialogue;” because imagined interactions is a broader concept that takes into account nonverbal and verbal imagery (Honeycutt 2008). Visual imagery reflects the scene of the interaction (e.g., office, den, and car). Verbal imagery reflects lines of dialogues imagined by the self and by others (e.g., I recall speaking to my boyfriend on my cell phone when he told me that he had just gotten tickets to a concert that we wanted to attend. I was happy at the news since the performance was in demand).

2.1 Procedures for measuring IIs

Post positivists believe that human knowledge is based not on unchallengeable, rock-solid facts or truths, but rather upon human conjectures or suppositions. As human knowledge is unavoidably conjectural, the assertion of these conjectures is justified by a set of warrants, which can be modified or withdrawn in the light of further investigation (Robson 2002; Zammito 2004). A variety of methods are triangulated to test the theory out of the recognition that observations and measurements are inherently imperfect. IIs are measured through surveys, journals, and interviews. However, it is also possible to use two induction procedures in which individuals have a proactive II before a real conversation. We use two procedures in this induction: 1) a talk aloud procedure in which they role-play a conversation about the issue and voice their anticipated responses, and 2) a dialogue script in which they write down their statements and the anticipated statements of the partner (Honeycutt 2008).

2.2 Attributes of IIs

There are eight attributes or characteristics of IIs. Frequency simply represents individual differences in how often individuals experience them. Some people have them throughout the day while others rarely have them. Proactivity and retroactivity are concerned with the timing of the II in relation to actual conversations. Proactive IIs occur before an anticipated encounter while retroactive IIs occur after the encounter. Retroactivity is very common in films and movies in which characters are shown having flashbacks. Proactive and retroactive IIs can occur simultaneously as individuals replay prior conversations in their minds while preparing for ensuing interactions. Discrepancy occurs when what was imagined is different from what happens in actual conversations. IIs are used for message planning. Hence, most of the imagined talk comes from the self with less emphasis being placed on what the interaction partner says. This reflects the self-dominance attribute. The variety characteristic of IIs reflects individual differences in the number of topics that are discussed in the IIs and whom they are with. IIs tend to occur with significant others such as relational partners, family, and friends. They do not occur with people we rarely see. Finally, IIs vary in their specificity or how vague the imagined lines of dialogue are as well as the setting where the imaginary encounter occurs.

3 Personality and imagined interaction

Early II research examined the attributes of IIs and their association with personality attributes, gender differences, marriage types, and relational quality (for a review, see Honeycutt 2003). Honeycutt (2010a: 205) states the following in terms of the association between personality and imagined interactions: “The attributes and functions of imagined interactions (IIs) may be measured after the most recent II as well as a general, personality trait depending on your research needs. Contextualization of Items: The characteristics and functions may be measured in terms of overall usage as well as in specific contexts or the most recent II. It is important to contextualize items for specific research domains. Hence, the items may be modified to specify a particular interaction partner, scene, or situation.”

Sample findings reveal the dysfunctional association between loneliness and IIs. Lonely individuals tend to have fewer IIs than non-lonely people, but when they have them; they are discrepant from what actually occurs (Edwards, Honeycutt, and Zagacki 1988). Discrepancy is also negatively associated with communication competence. Lonely people have limited prior interactions upon which to base their IIs, so imagined interactions they experience prior to new interaction are likely to be high in discrepancy. The personality characteristic of locus of control in which people believe they are in control of their destiny and the environment is negatively associated with retroactivity but positively associated with having a variety of IIs; perhaps to figure out why they are victims of fate in so many instances (Honeycutt, Edwards, and Zagacki 1989–90).

Conversational sensitivity reflects a personality disposition to detect meanings, recall conversations, affinity, and eavesdropping enjoyment as well as interpret what is said (Daly, Vangelisti, & Daughton 1987). Having retroactive IIs over a variety of interaction partners and topics that are specific is associated with overall conversational sensitivity (Honeycutt, Zagacki, and Edwards 1992–93). Honeycutt (2003, 2010c) also has found that having frequent and proactive IIs that are specific in imagery is associated with verbal aggression where people use personal, verbal insults to attack another person’s character.

More recently, a study by Honeycutt, Pence, and Gearhart (2012–2013) examined the associations between II attributes and the Big Five personality traits. In terms of personality, IIs have trait characteristics to the extent they are enduring and stable across similar conditions. Conversely, they can also be measured in terms of state characteristics in which their usage would be higher or lower depending on the particular context.

The Big Five Personality Traits include the following: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness. Neuroticism is characterized by “a tendency to experience negative affect, such as anxiety, depression or sadness, hostility, and self-consciousness; as well as a tendency to be impulsive” (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996: 777). Extraversion is characterized by a tendency to experience “positive emotions and to be warm, gregarious, fun-loving, and assertive” (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996: 777). Those scoring high on the third dimension, openness, tend to be “curious, imaginative, creative, original, artistic, psychologically minded, and flexible” (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996: 777–778). Agreeableness “has been found to be the opposite pole of antagonism … (It) reflects a proclivity to be good-natured, acquiescent, courteous, helpful, and trusting” (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996: 778). Conscientiousness “has been found to be the opposite pole of undirectedness … characterized as having a tendency to be habitually careful, reliable, hard-working, well-organized, and purposeful” (O’Brien and DeLongis 1996: 778).

The data reveal that the frequency and proactivity attributes of imagined interactions are correlated with lack of neuroticism and openness. Neuroticism increases egocentrism, depression, and anxiety (Hamilton et al. 2009). High anxiety is characterized by being more worrisome in general than those who are non-anxious, and it is from this assumption that the correlation is explained. Highly anxious people would indeed have less frequent IIs as means to predict their believed unstable environment. Additionally, frequency was also correlated with the personality dimension of openness – openness being defined by the scale questions, such as “likes to reflect”, “active imagination”, and “deep thinker” (John, Donahue, and Kentle 1991). The assumption these researchers made is that openness and frequency are correlated because these people are extraverts. Analysis of that assumption proved it to be true, as the correlation between extraversion and openness was significant. Indeed, people who are extraverted are more likely to imagine themselves frequently interacting with other individuals.

These findings are interesting in view of poetic imagination. Over a century ago, Freud (1908) discussed poetic imagination in terms of the dialectic relationship between creativity and reality. Freud argued that creativity is typically presented in terms of fantasy, daydreams, and nocturnal dreaming. Frequency is related to neuroticism and openness. Freud notes that secretly people daydream because of unfulfilled desires. This belief reflects the imagined interaction characteristic of discrepancy. Through poetry, readers are helped to participate in daydreaming in terms of unconscious wish fulfillment in tragedy or heroics. Fantasy in the work of art provides relief from the harshness of reality. Freud claimed that “happy people never make fantasies, only unsatisfied ones. “Unsatisfied wishes are the driving power behind fantasies; every separate fantasy contains the fulfillment of a wish, and improves on unsatisfactory reality” (Freud, 1908: 37).

Additional significant findings revealed that having non-discrepant IIs that are pleasant with the self talking more in the II is moderately associated with the personality dimensions of extraversion and conscientiousness. The explanation for the link between experiencing self-dominant imagined interactions and extraversion is clear- extraverts by nature interact with more individuals than do introverts, so extraverts would therefore imagine themselves having these interactions more often than those who are not extraverted. Another finding from their study is that extraverts have more pleasant IIs- this is explained through another relationship between extraversion and narcissism. Extraverts therefore think highly of themselves, and most likely portray themselves in a pleasant manner in their imagined interactions.

An interesting finding is the correlation between extraversion and non-discrepancy. It seems plausible that people who more frequently interact with others would be better predictors of how a given situation is going to turn out, due to a plentitude of past experience. Additionally, there is an association between conscientiousness and non-discrepant IIs. This finding is explained via the items used to measure conscientiousness, which reflect traits such as “is reliable”, “does through job” (John, Donahue, and Kentle 1991). People who are more thorough are more likely to be prepared for social interactions (and, for that matter, interactions in general); given this proclivity, the experiences they have in reality should mirror their through imagined interactions.

4 Functions of IIs

While several II attributes have been identified, there are six functions that research has revealed. More specifically, imagined interactions function in the following ways: (1) they compensate for lack of real interaction, (2) they maintain conflict as well as resolving it, (3) they are used to rehearse messages for future interaction, (4) they aid people in self-understanding through clarifying thoughts and feelings, (5) they provide emotional catharsis by relieving tension, and (6) they help maintain relationships through intrusive thinking about a relational partner outside of their physical presence. Of course, too much intrusive thinking reflects obsession. The following is a brief review of each function.

Compensation is the inability to actually communicate with someone; so introspective thought substitutes for the lack of opportunity to talk. The compensation function is rampant during electrical outages or when cell phone towers are blown down during tornadoes, hurricanes, or other environmental disasters (Honeycutt and Mapp 2011). From their early development, IIs have been purported to take the place of real interaction when it is not possible to actually communicate with a given individual. In their discussion of IIs used for counseling, Rosenblatt and Meyer (1986) indicate that an individual may choose to use IIs in place of actually confronting a loved one for fear that the loved one would be hurt by the message. Honeycutt (1989) discusses the use of IIs as a means of compensation by the elderly who may not see their loved ones as often as they would like.

Boldness has been identified as a possible function of IIs, but it appears to reflect compensation. McCann and Honeycutt (2006) discussed how individuals may feel “emboldened” in situations where there are sanctions for voicing opinion. They found that the Japanese used IIs more to suppress communication and as mean for voicing disagreement because they felt empowered in their imaginary conflicts since there would be no repercussions. Indeed, scholars have described the highly elaborate rules of manners and conduct in Japan that include compliance to others, self-restraint (passivity), suppression of inner feelings, observance of formal greetings and speech, and appropriate gestures (Rothbaum et al. 2000). McCann and Honeycutt (2006) concluded that IIs might have served as a “safe,” punitive-free outlet for self-expression for their Japanese participants. To the Thais and Americans, who perhaps operate under comparatively less rigid norms for individual expression (Embree, 1950; Triandis, 1995), this “safe” II outlet may not have been as necessary.

Cross-cultural research comparing the imagined interactions of Americans, Japanese, and the Thais reveals that the Japanese participants use the boldness function to escape from societal norms via their IIs, more than the Thais and Americans. Additionally, the Japanese and Thais reported that they keep conflict alive via their IIs more than the Americans, whereas the Thais utilize the II rehearsal and self-understanding functions the least.

A second function of IIs is managing conflict; also referred to as conflict linkage because a series of conversations are linked together in the mind in terms of serial arguing. Serial arguing occurs when people repeat the same arguments over multiple interactions. Imagined interactions help us manage conflict as individuals replay old disagreements with loved ones. Research on rumination and depression reveals that it is difficult to either forgive or forget despite the cultural maxim to the contrary (McCullough et al. 2001).

This function has resulted in a secondary, axiomatic theory consisting of three axioms and nine theorems that explain the persistence and management of daily conflict (Honeycutt 2004). The axioms are concerned with how relationships are conceptualized in terms of thinking about relational partners outside of their physical presence. Hence, IIs occur with important people in our lives including loved ones, work associates, and rivals. There is the assumption that a major theme of relationships concerns balancing cooperation and competition (Honeycutt and Bryant 2011). This balance is discussed later in the context of II conflict-linkage theory.

Rehearsal in the form of message planning is the third function. II research has examined planning and message rehearsal. For example, rehearsal has been analyzed in relation to attachment styles. Regression analysis revealed that a secure attachment is predicted by rehearsal as compared to other attachment types (Honeycutt 1998–99). Perhaps strategic planning for various encounters may enhance security in romantic relationships. This use of IIs seems also to be linked to cognitive editing, which allows adjustments to messages after their potential effects on a given relationship have been assessed (Meyer 1997).

Proactive IIs are a means by which to plan anticipated encounters. Plans are broader than IIs since rehearsal is just one function. Plans may be nonverbal in the pursuit of actions or goals (e.g., realizing it’s your anniversary coming up and buying a gift that does not involve any communication). When used for rehearsal, IIs allow for a decrease in the number of silent pauses and shorter speech on-set latencies during actual encounters and allow for an increase in message strategy variety (Allen and Honeycutt 1997).

The fourth II function is self-understanding which serves to aid people in uunderstanding themselves better as they help to uncover opposing or differing aspects of the self (Honeycutt, 2008). More specifically, this function is concerned with the self understanding the basis for their beliefs, attitudes, values, opinions, and ideology. For example, why do people believe in corporal punishment if they have to discuss this issue with someone else? Hence, introspective thinking may be used in order to understand the etiology of beliefs. Although less research has been done on this function, Zagacki and his associates (1992) indicated that those IIs involving conflict increase understanding of the self. Self-understanding involves more verbal imagery with the self playing a greater role in the II, or being more dominant. Catharsis is the fifth function in which people use IIs to relieve tension and anxiety which further reduces uncertainty. IIs provide a mechanism to internally get “things off of one’s chest” and release emotions.

The final function, relational maintenance is concerned with intrusive thinking in which individuals think about interaction partners. Imagined interactions (IIs) help sustain relationships. People often imagine talking with others that are important in their lives. Research reveals that relational happiness is associated with having pleasant IIs (Honeycutt and Wiemann 1999; Honeycutt 2008–09). Furthermore, engaged couples who were more likely to live apart used IIs to compensate for the absence of their partner compared to married couples. Honeycutt and Keaton (2012–2013) found that having more specific, frequent and pleasant IIs was positively associated with relational satisfaction. Additionally, increased uses of proactive and retroactive IIs aided the ability of imagined interactions to predict relational quality. Furthermore, relational satisfaction was simultaneously predicted by extraversion and being a judger based on the Myers-Brigg personality inventory in which judging reflects placing a premium on organized environments, competence, performance and independence. The finding that extraversion has been more typically associated with positive affect and well-being would signify a positive association with relationship satisfaction. Additional personality findings are discussed below.

5 Correspondence between II attributes and functions

Although II theory has been a productive framework for research on communication and social cognition, there is an underlying and yet untested assumption within II theory that the eight attributes are related to all six functions and that II functions can be compared and contrasted in terms of II attributes. Recently, Bodie, Honeycutt, and Vickery (2013) conducted two studies exploring the multidimensional nature of functions and attributes. The first study revealed both corroborative and counter evidence for II theory. In line with the internal structure of II theory, it was found that conflict linkage and catharsis IIs are more negatively valenced than those used for compensation and relational maintenance. Rehearsal IIs are more likely to be discrepant than all functions except relational maintenance and are the most proactive. When compared to all other functions, compensatory IIs contain references to more people and were more frequent. It also appears that compensatory and relational maintenance functions are similar insofar as each is equally directed to others and highly specific, providing support for the role of each in close interpersonal relationships (Honeycutt 2003). Relational maintenance and conflict IIs were used just as frequently as those for catharsis, and relational maintenance IIs were directed toward others in an equivalent manner as those used for conflict.

In the second study, employing canonical correlation analysis, II attributes were simultaneously correlated with II functions that yield three dimensions. The first dimension contained all functions except compensation and all attributes except frequency. The second dimension contained the compensation, conflict, and self-understanding functions along with five of the eight attributes (excluding both timing attributes and specificity). The final dimension contained the functions of catharsis, conflict, and relational maintenance along with the discrepancy and dominance attributes. Thus, when using IIs to manage relationships and handle conflict with the absence of emotional catharsis, people report them to be more self-dominant and less discrepant.

Both studies confirmed that conflict linkage and catharsis IIs are more negatively valenced than those used for compensation and relational maintenance; rehearsal IIs are more likely to be discrepant than all functions except relational maintenance and are the most proactive. When compared to other functions, compensatory IIs contain references to more people and were more frequent. Careful examination of the nuances of the three canonical dimensions, however, reveal some differences from the results in Study 1. For example, in Study 2 IIs used for rehearsal had a negative loading on the first canonical dimension while pro and retroactivity had positive loadings; however, in Study 1 IIs used for proactivity were most associated with rehearsal and least associated with retroactivity. So how are such differences between these studies reconciled? One explanation has to do with measurement. Honeycutt (2010) discusses how IIs may be assessed through triangulation of measures including surveys, qualitative journal accounts, interviews, and the induction of IIs using a talk aloud procedure and written protocols. He has reviewed the literature on the veridicality of retroactive reports of cognitive processes. Furthermore, as indicated earlier, Honeycutt (2010) offers precise instructions for contextualizing items from the Survey of Imagined Interaction. The first study used contextualized items while the second study did not. Hence, the correspondence between attributes and functions measured as a trait in the second study revealed different findings than when contextualizing attributes within each function as was done in the first study.

6 Personality and II functions

Neuroticism is associated with the imagined interaction function of catharsis and a lack of conscientiousness is compatible with Freud’s (1908) discussion of neuroticism and poetic imagination. Freud (1908) contended that neurotic individuals have a tendency to engage in too many “flights of fancy” that distract from the reality of the present moment (cf., Klinger 1980) and cannot constructively negotiate the dialectical tension between reality and fantasy. Neuroticism increases egocentrism, depression, and anxiety (Hamilton et al. 2009). Additionally, Hamilton and his associates (2009) suggest that anxious, depressed people are likely to find catharsis (“relieve tension and reduce uncertainty” as described by Honeycutt (2010b) through the act of imagined interactions; in fact, the imagined interactions that people who are low on neuroticism are likely to have are increasingly positive in terms of valence (see Honeycutt, 2010c, for further explanation on negative affect and rumination). Additionally, people who lack conscientiousness (i.e., “don’t do a thorough job”) tend to be more anxious (increase in neuroticism) about interactions because they are likely to not be prepared for them.

An additional finding is the relationship between relational maintenance and neuroticism as well as lack of conscientiousness. John, Donahue, and Kentle (1991) partially defined a conscientious person as someone who “isn’t lazy”; assuming that people who lack conscientiousness are indeed lazier, the relationship between relationship maintenance and neuroticism becomes clear. Relationship maintenance requires more than simply having imagined interactions involving one’s partner; relationship maintenance means actively interacting with the partner to create a healthy relationship. One possibility is that lazy individuals do not take an active role in their relationships; future research should examine this possibility.

Additional research on neuroticism and perceived social support sheds light onto the finding that links relational maintenance and neuroticism. Swickert and Owens (2010: 388) found that “females who are high in neuroticism experience increased levels of negative affect, which may lead to greater dissatisfaction within highly neurotic females’ social relationships as compared to females who are low in neuroticism.” Additionally, Swickert and Owens (2010) stated that neurotic individuals experiencing stressful events are more likely to perceive the incidents in a pessimistic manner. The findings indicate that those high in neuroticism possibly see stressful situations in a more pessimistic light than those low in neuroticism, and that those high in neuroticism perceive a lack of social support from their partners (Swickert and Owens 2010). There are numerous other studies showing the relationships between other personality traits and IIs (Honeycutt 2010c). The studies reviewed here also demonstrated that the primary epistemology of IIs can be described as post-positivist (Honeycutt 2008), an issue that is briefly discussed below.

7 Conflict-Linkage Theory

The conflict linkage function of IIs explains pervasive conflict in personal relationships and the difficulties in managing conflict in constructive ways. This function has resulted in the development of a secondary, axiomatic theory consisting of three axioms and nine theorems that explain the persistence and management of daily conflict (Honeycutt, 2004; Honeycutt and Bryan 2011). The axioms are concerned with how relationships are conceptualized in terms of thinking about relational partners outside of their physical presence. Hence, IIs occur with important people in our lives including loved ones, work associates, and rivals. This secondary theory assumes that a major theme of relationships is concerned with balancing cooperation and competition. Indeed, a pioneer study on the dimensions of interpersonal relationships revealed that people view the relationships of others and ones they are involved with along four bipolar dimensions, one of which is competition versus cooperation (Wish, Deutsch, and Kaplan 1976). Recently imagined interaction conflict-linkage theory has been examined in serial arguing (Wallenfelsz and Hample 2010) with results providing support for various theorems.

The conflict linkage function of IIs highlights the role of rumination in which people have recurring thoughts about conflict and arguing that make it difficult to focus on other things. Research on rumination and depression reveals that it is difficult to forgive or forget despite the cultural maxim to the contrary (McCullough et al. 2001). Rumination about prior conflict is associated with depression, hopelessness, and lack of motivation (Honeycutt, 2003). McCullough et al. (2011) discuss how rumination is also associated with vengefulness, as people reflect on the injustices and harm they have suffered. Indeed, people believe that their rumination facilitates focusing on balancing the scales, retribution, or saving face, even though studies reveal that rumination is actually associated with poor problem solving (Nolen-Hoeksema 1991). A comprehensive discussion of the various theorems and the research supporting them can be found in Honeycutt (2003, 2004, 2010c).

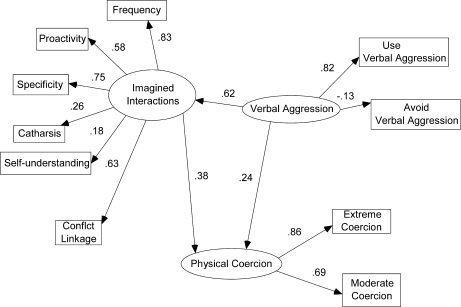

Fig. 1: Standardized Mediational Model of Imagined Interactions, Verbal Aggression, and Physical Coercion.

Honeycutt and Bryan (2011) tested a model in which IIs mediated the relationship between verbal aggression and physical coercion or abuse. Essentially, this means the abuser is thinking about his/her actions and verbal taunts. Characteristics of this type of imagined interaction as revealed in Figure 1 are having frequent IIs (activity) that occur before the incidents (Proactivity) that reflect conflict linkage. Yet, the loading of the specificity factor (.75) on imagined interactions reflects the idea that the abuser is thinking of relatively precise visual and verbal images. For example, he/she anticipates what they are going to say at the anticipated encounter as well as imagining the scene of the interaction. The imagined interaction is characterized by repetitive thoughts about the areas of conflict. For examples, individuals replay arguments in their mind while simultaneously preparing for the next encounter. In addition, the catharsis index is slightly related to imagine interactions in this context as the abuser may report feeling better by using imagined interactions to relieve pent-up emotions, tension, and stress in their mind. Indeed, one of the catharsis items assesses the extent that people report IIs help to get “things off their chest.” To the extent IIs partially mediate the association between verbal aggression and physical coercion, communication intervention may be used for the abuser who plans their violence. Indeed, communication intervention may foster the role of forgiveness which has been shown to be negatively associated with rumination about seeking revenge (McCullough, Bono, and Root 2007).

Data on serial arguing reveal that the degree to which one personalizes conflict is associated with both rumination and imagined conflict interaction (Wallenfelsz and Hample 2010). Taking conflict personally is a stable personality trait and temporary trait (Hample and Dallinger 2005). Yet, conflict is more likely to be taken personally if the conflict is stressful or if there is a perception of inequity or aggression. Taking conflict personally may be manifested as aggression or avoidance, and can result in reciprocal reactions. Theorem 3 of II conflict-linkage theory proposes that negative IIs intrude when an individual attempts to purposely creative positive IIs as a therapy for conflict. A reason for this intrusion may be the tendency to take conflict personally. Wallfenfelstz and Hample (2010) found that that II valence correlated positively with taking conflict personally. People who enjoy conflict also tend to enjoy imagining conflict. Additionally, individuals who believe that conflict has a positive effect on relationships tend to have more pleasant IIs about conflict than those who do not.

Hample, Richard, and Na (2012) conducted an empirical test of the conflict-linkage model in terms of serial arguments. These arguments can be trivial even though they recur, but they can also be quite consequential for one’s relationship and personal health (Johnson and Roloff 1998; Malis and Roloff 2006; Roloff and Reznik 2008). The imagined interactions can create self-fulfilling prophecies and can also be cognitive records and reflections on the actual episodes. Evidence favoring the theory would show that attributes of imagined interactions predict features of serial arguments and that the arguments influence the elements of the imagined interactions. Hample and his colleagues found that the willingness to hurt other in order to benefit self increased with activity and the prominence of the other person in the imagined interactions. Mutuality was increased by positive valence for the imagined interaction. The impulse for negative expression was increased by retroactivity and low variety. High activity implicated a clear focus on decided whether or not to progress in the relationship. The desire to change the other person was increased by high discrepancy, proactivity, and retroactivity, but reduced with high variety. Hample and his associates concluded the following:

What seems to be going on is that the imagined interactions have a consistent character of their own, and so offer a standard platform from which people enact their conflicts. People have consistency in the features of their imagined interactions across various communication episodes (Honeycutt 2003). The essential causal process seems to be that imagined interactions remain fairly consistent with one another, more or less regardless whatever happens in the world of actually enacted interpersonal communication. Rather than the communication episodes having very much to do with the imagined interactions, the imagined interactions are a continuing set of causal influences on the behaviors. This is not the only causal process going on, because we found some influence from the episodes to the imagined interactions. But we believe we have evidence that the imagined interactions have more to do with the nature of the episodes than the episodes have to do with the imagined interactions (Hample, Richards, and Na 2012: 476).

While arguing or even ruminating about conflict, it is common for people to become vigilant, energized, focused, and fly into rages. As a consequence, research has examined physiological arousal while thinking about arguments as well as during arguments. The notion of physiological linkage is discussed next.

8 Physiology and IIs

Honeycutt (2010d) discusses the importance of physiological variables in order to measure imaging. Physiological data complement existing methods for measuring II including surveys, interviews, and observation of individuals discussing recent conversations which reflect retroactive imagined interactions. Additional measures include a “talk out loud” procedure in which individuals role-play what they might say in a conversation and how they envision the partner responding.

Consider a study of positive and negative emotional affect in discussing issues in intimate relationships such as exclusive daters or intimate Facebook friends. We measure the physiological arousal of couples who are asked to imagine either discussing a topic that they are highly pleased with (e.g., sharing time together) or displeased with (e.g., how they communicate) and then to actually discuss the topics. The former is referred to as an induced imagined interaction. We observe positive and conflictual interaction in the Matchbox Interaction Lab at our university (see link: http://appl003.lsu.edu/artsci/cmstweb.nsf/$Content/Match+Box+Interaction+Lab?OpenDocument) The laboratory resembles a living room, containing a comfortable coach, easy chair, coffee table, magazines, and paintings. Most physiological measures are not under conscious control; hence, physiological measures offer a means of circumventing the self-presentation bias that is endemic to observational studies of communication. Because imagined interactions are characterized by a variety of emotions and emotional intensity, it is prudent to measure heart rate in positive and negative II conditions. Conflict is associated with adrenalin and these emotions (Gottman, 1994).

8.1 Physiological arousal

Our ancestors’ physiology evolved to deal rapidly with physical threats such as fighting a rival for food or fleeing from predators (Sapolsky 1998). In contemporary society, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) becomes activated when faced with a psychological or social threat. The SNS is part of the autonomic nervous system that tends to act in opposition to the parasympathetic nervous system, as by speeding up the heartbeat and causing contraction of the blood vessels. It regulates the function of the sweat glands and stimulates the secretion of glucose in the liver. The sympathetic nervous system is activated especially under conditions of stress. For example, one may be faced with a crucial deadline, one is cut off by a driver in traffic, and one wonders what others think about one’s work at a job. Once activated, the SNS releases epinephrine, norepinephrine, and coritosol into the bloodstream. Correspondingly, there is increased respiration, blood pressure (BP), heartbeat, and muscle tension.

The second part of the autonomic nervous system is the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The PNS acts to dampen the effects of the SNS: Its activation decreases heart rate, increases digestion, and so on. Hence, the relaxation response turns SNS arousal off by turning on the PNS. So, in essence, one doesn’t really control the relaxation response; instead, one does the things that result in the PNS taking control.

Physiological arousal involves the autonomic nervous system in a state of adrenalin release and includes pulse (heart rate beats per minute [bpm]), interbeat intervals (IBI), and somatic activity measured in terms of a wrist monitor. IBI is a measure of the time in milliseconds between adjacent heart beats. High IBI rates are related to increased levels of adrenalin, anxiety, and arousal (Porges 2011). The lower the IBI value, the shorter the cardiac beat, which reflects a faster heart rate. Under normal conditions, the heart’s rate is under control of the PNS. Baseline measures of heart rate are taken before participants are exposed to experimental stimuli, and the baseline measure and age are used as a covariates in analyzing subsequent mean differences between experimental groups.

The importance of measuring heart rate variables cannot be stressed enough. Research by Childre and Martin (1999) revealed that the heart helps us respond to environmental cues through the production of mood-enhancing hormones. The electromagnetic signal that the heart sends to the brain and every other cell as well is the most powerful signal in the body (Hughes, Patterson, and Terrell 2005). Furthermore, Damasio (2003) presented evidence that individuals cannot make decisions without processing emotional information that incorporates beliefs about how positive and negative the situation is. These judgments actually reflect the synthesis of both heart and brain functions weaving together cognition and emotion in a joint, intertwined fabric.

8.1.1 Physiological linkage in social interaction

Gottman (1994: 72) defined the notion of physiological linkage in distinguishing happy from unhappy couples in which there would be a reciprocity of negative affect (misery loves company) as well as temporal predictability and “reciprocity in physiology” in physiology as well. A pioneering study by Kaplan et al. (1964) paired people on the basis of mutual liking or disliking and they found that predictability from one person’s electrodermal response to another person only existed for people who disliked each other. Simple correlations were used to measure the extent of physiological relatedness between partners. There are serious problems with using bivariate correlations because physiological data including heart-rate variability are cyclical and can be autocorrelated. Actually, this is both strength and a weakness for case studies. Most studies rely on sample size and the unit of analysis is the number of cases, but for case studies, there is only one case. Yet, the strength is that unit of analysis is that IBI is measured in milliseconds and there are multiple data points. Conversely, heart-rate averages usually are measured in terms of average beats per minute. Hence, for a five-minute observation, there would only be five data points.

A weakness has to do with autocorrelation. This means that data can be forecast from their past. As Gottman (1994: 73) notes, “if data can be forecast from their past, it is difficult to make inferences about linkages between variables.” Hence, if IBI can be predicted from previous values, it is difficult to estimate how IBI between relational partners while having imagined interactions on pleasing or displeasing topics (again, it may be a substantive recurring topic that typically elevates adrenalin, thereby increasing IBI). The solution is to statistically test for the presence of autocorrelation at different time periods or lags and remove the autocorrelation. Informally, it is the similarity between observations as a function of the time separation between them. Statistical removal of the autocorrelation yields an unbiased indicator of physiological linkage between two people.

The following is a case study of an engaged couple that had a long-distance relationship for a period of 6 months. He was 25 and she was 23. He was in graduate school and was spending a semester overseas in a cultural exchange, internship program studying Dutch pumps. His fiancée was studying social work. Each person completed an induced II. He imagined discussing with his fiancée a pleasing topic which was their shared goals and interests including their desire to go on a cruise and a displeasing topic (his separation from her while he would be away). Her pleasing topic was how open she felt he was in communicating with her revealing flexibility and disclosure. Her displeasing topic was also the separation due to the cultural exchange program. Both partners used the talk aloud procedure to have their II which lasted three minutes. They then discussed the displeasing and pleasing topics with each other. Each person’ IBI was assessed during their individual IIs and the discussion afterward. Comparing his heart rate in the II induction with his heart rate while actually discussing a pleasing topic with his partner resulted in a cross-correlation of .10, while it was .17 when compared to her discussing her pleasing topic. Essentially, these low correlations reveal no physiological linkage between the partners. Originally, Gottman (1994) indicated that physiological linkage occurred more often among unhappy couples than happy couples. This couple was relatively happy. The strongest sign of physiological linkage occurred when both partners were discussing their pleasing topic (partial r = .25). Conversely, when discussing their displeasing topics, the partial cross-correlation was only .10. Additionally, a repeated measures analysis of covariance in which heart rate variability measured in a baseline, resting state for a period of two minutes before the induced II revealed that the male had larger heart-rate variability than the female during the induced II session, F(2, 376) = 4.19, p = .016. Follow-up, t-tests revealed he had a higher IBI (M = 699.83, SD = 57.80) during the induced II than she did (M = 642.91, SD = 64.24; t(656) = 17.58, p = .000. Hence this finding indicates that he had a lower rate heart rate during the induced II.

The same pattern occurred for discussing the pleasing and displeasing topics. Yet, it is worth noting that his highest IBI occurred when discussing the displeasing topic (M = 718.74, SD = 61.72) while her IBI was lower (M = 617.06, SD = 55.32; t(221) = 19.83, p = .000. Therefore, she had a higher heart rate while discussing the displeasing topic of separation than he did. It is plausible that since she was staying behind during the separation, she felt lamentation or sadness while he felt the excitement of traveling abroad. Consequently, her lamentation may have been manifested in her elevated heart rate during this discussion. Consistent with this possibility, in a post-experiment debriefing she indicated how she felt left out while he was going to be away and she was disappointed with the situation.

8.1.2 Physiology of IIs and road rage

We have measured change in adrenalin and anxiety levels in terms of imagined interaction and emotion as automobile drivers are “venting” at offending drivers in heavy traffic conditions when they are late for an important meeting with business clients (Honeycutt 2006). We have employed Applied Simulation Technologies that are used to train state police officers in driving skills. Aggressive driving reflects lack of dialogue with the offending driver. It represents the I-It metaphor in which the self is stereotyped, as being “good” while the offending driver is “evil.” However, even in some road rage incidents, there are anecdotal reports of dialogue with passengers who may encourage the driver to be aggressive. Indeed, social comparison theory could be operating in the situation in which there is a diffusion of responsibility, as car occupants may feel uninhibited in expressing coercive actions. Hence, we have compared driving alone with a condition in which the driver has an intimate partner (e.g., spouse) as a passenger (Honeycutt 2010d).

There are individual differences in having imagined interactions while driving. Some of the personality differences in driving profiles involve being an angry, impatient, competing, or punishing driver. We have measured the use of IIs for venting at offending drivers reflecting the catharsis and conflict-linkage functions. The presence of passengers, music, weather conditions, drinking patterns, driving personality profiles are correlated with aggressive driving tendencies including acceleration, braking, swerving, and tailgating.

We have found consistent correlations (Honeycutt 2010d). For example, partial correlations controlling for the baseline level of heart rate beats per minute (BPM) and the baseline heart rate variability have revealed that while driving a car in heavy traffic conditions in which a person is late for an important meeting and is being boxed in by an offending driver who is using a cell phone; heart rate BPM is negatively correlated with using IIs to vent at other drivers (partial r = –.36). Venting at other drivers is associated with tailgating distance in which the driver in heavy traffic pulls up to the vehicle that is immediately in front of them (partial r = .37). We have found that using IIs to vent at other drivers is associated with being a punishing driver, such that the car is used as a weapon, being an impatient driver, and being a competitive driver. While venting, the driver is certainly not apprehensive about communicating. Part of this may be due to the “security” of being in the car; while it could be different if the drivers faced each other on a parking lot. The relationship between different types of communication and apprehension is discussed next.

9 Using IIs to alleviate Communication Apprehension

Since the time of its conceptualization, communication apprehension (CA) has been the subject of extensive study within the field of communication. According to McCroskey (1977: 78), CA can be defined as “an individual’s level of fear or anxiety with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons.” A critical word in this definition is “anticipated” and it is important to note that the anxiety regarding a future communicative encounter can be as powerful as the real interaction itself. The transitive verb, anticipated, implies foresight which implies proactive IIs. Recall that a major attribute of IIs is proactivity in which individuals envision encounters beforehand in order to rehearse messages. We have examined how catharsis and rehearsal functions of IIs as well as discrepancy facilitating or reducing the level of CA in conversations, groups, meetings, and public speaking (Honeycutt, Choi, and Deberry 2009).

CA can be thought of as an experienced feeling of discomfort resulting in ineffective communication when experienced in high amounts. CA can also be defined as an individual’s “… anxiety syndrome associated with either real or anticipated communication with another person or persons” (McCroskey 1977: 28). Many studies have examined overall CA as an enduring personality disposition across different communication contexts and across time (e.g., Daly et al. 2009). However, we examined CA in terms of a contextual approach across dyadic conversations, group meetings, and public speaking. Individuals with high CA tended to avoid thinking about impending interviews, and instead focused on note taking for preparation (Ayres et al. 1998). Honeycutt and his associates (2009) found that II catharsis was negatively associated with CA only within the public speaking context.

The discrepancy characteristic of IIs is of relevance to CA since previous research indicates that introversion, shyness, and loneliness are all associated with high levels of CA. For instance, Opt and Loffredo (2000) observed that individuals with high CA levels also exhibited high levels of the personality trait of introversion. Such findings are consistent with Richmond and McCroskey’s (1998) work demonstrating that individuals with high CA levels have fewer interpersonal relationships and increased levels of shyness compared to individuals with low levels of CA. The relationship between loneliness and CA is thus well documented as Honeycutt and his colleagues (1990) found that loneliness was related to II discrepancy. Indeed, there is a positive association between discrepancy and all types of CA whether it is in dyadic communication, groups, meetings, or in public speaking.

The study also revealed that discrepancy was a significant predictor of CA. This finding is contrary to prior research which suggested that individuals with high CA levels focused on non-communicative rehearsal methods, such as note taking (Ayers et al. 1998). Yet, their findings suggest that although individuals high in CA might focus more on note taking, the note taking is accompanied by mental rehearsal. The implication is that regardless of their CA standing, individuals rehearse for interactions at similar levels which are often discrepant. Therefore, discrepant IIs have the potential to act as “catastrophizing” agents when individuals imagine the worst case scenario, and the II becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy (Honeycutt and Ford 2001).

Currently systematic desensitization, cognitive modification, and visualization are used to treat individuals with high levels of CA. Systematic desensitization involves the construction of hierarchies of anxiety producing events, the graduated paring of anxiety-eliciting stimuli, and deep muscle relaxing techniques (Friedrich and Goss 1984). In using cognitive modification, anxious individuals are encouraged to identify their negative rehearsal statements and replace them with positive rehearsal statements (Glaser 1981). Finally, in the case of visualization individuals are encouraged to picture themselves succeeding in the communication situation. The data presented by Honeycutt and his associates (2009) suggest that cognitive modification would be the most appropriate because the technique specifically addresses negative discrepancy. However, repeated replication of these findings among more diverse samples is need before any substantial changes to CA treatment techniques can be advanced.

10 Summary

There are different levels of communication ranging from the most individualistic to the most collectivistic. Intrapersonal communication is the foundation of all human communication and should be recognized as such. A major mechanism for analyzing intrapersonal communication and social cognition is through the study of IIs. They are frequently used in everyday life and serve a variety of functions including understanding, rehearsal, conflict management, relational maintenance, catharsis, and compensation. They are associated with personality, quality relationships, ability to argue, and mental health. Retroactive IIs are often portrayed in movies or television in the form of flashbacks.

Moreover, individuals often confuse imagined interactions with fantasies. Caughey (1984) discusses fantasy as a type of daydreaming in terms of a sequence of mental images that occur when attention drifts from focused rational thought. On the other hand, IIs simulate conversational encounters that individuals expect to experience or have experienced during their lives. Some of these encounters may never transpire or they may be quite different from what was envisioned. Yet, communication fantasies involve highly improbable or even impossible communication encounters (Edwards, Honeycutt, and Zagacki 1988). For example, it would be a fantasy to imagine talking to the President of the U.S. if one did not personally know him and the probability was low that one would ever meet him face-to-face or correspond via e-mail. Common fantasies occur among so-called “groupies” who follow celebrities and believe that they intimately know the celebrities in terms of para-social relationships.

As discussed in the present chapter, considerable research has involved how conflict is repetitive and festers within an individual. Hence, there are cultural maxims such “I can forgive, but cannot forget.” Enduring conflict is manifested within the human mind as individuals sometimes become caught in an absorbing state of recall old arguments. Indeed, recurring arguments can be likened to malignant cancer as it metastasizes and spreads. II conflict-linkage theory explains the recurrence of arguments and IIs mediate the relationship between verbal aggression and physical coercion. While anticipating arguments, individuals may rehearse what they are going to say as well as have online IIs during ongoing actual conversations. People often have retroactive IIs or flashbacks causing rumination in which conflicts are continually manifested within their minds. Research has revealed the connection between physiological arousal while thinking about arguing and while arguing. Studies of couples who imagine discussing pleasing and displeasing topics reveal that various levels of heart rate variability accompany IIs and actual discussions. Moreover, this work extends to practical activities including driving and so-called road rage where people may vent at “offending” drivers.

Finally, research reveals that people who are highly apprehensive about giving speeches have catharsis while imagining the speech. This makes sense as the catharsis function is designed to relieve tension and anxiety. The fact that II discrepancy was associated not only with overall CA, but also of CA in four specific contexts has important implications for treatment. In cognitive modification, individuals are encouraged to identify their negative rehearsal statements and replace them with positive rehearsal statements (Glaser 1981). This means having positively valenced IIs before speaking. Yet, this advice is not new and indeed reinforces classic advice given over 60 years ago by Norman Vincent Peele. He authored a book titled, “The Power of Positive Thinking” (Peele 1952). Of course, he was unaware of the various contingencies affecting optimism such that the advice is too simplistic and may backfire to the discrepancy between what was positively imagined and what actually occurs (e.g., think of a failed, last second field goal and the repercussions for the football kicker). Still, we believe that Peele’s advice is more right than wrong based on numerous studies of optimism and pessimism in psychology. On this note we conclude with the following advice: Have positive IIs that serve a rehearsal function so that even if they prove to be discrepant, one is in a stronger position to adapt to the changing situation. Indeed, the power of planning often allows people to anticipate contingencies and more quickly adapt to the circumstances (Berger 1997; Honeycutt 2003). Enjoy your imagined interactions for they may be serving a catharsis function for you.

References

Ayres, Joe., Tanichya Keereetaweep, Pao-En Chen and Patricia A. Edwards. 1998. Communication apprehension and employment interviews. Communication Education 47: 1–17.

Berger, Charles R. 1997. Planning Strategic Interaction. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Bodie, Graham. D., James M. Honeycutt and Andrea J. Vickery. 2013. An analysis of the correspondence between imagined interaction attributes and functions. Human Communication Research 39: 157–183.

Cunningham, Stanley B. 1989. Defining intrapersonal communication. In Charles V. Roberts, Kittie W. Watson, and Larry L. Barker (eds.), Intrapersonal Communication Processes 82–94. New Orleans, LA: SPECTRA/Gorsuch-Scarisbrick.

Daly, John A., James C. McCroskey, Joseph Ayres, Timothy Hopf and Ayres, D. M. 2009. Avoiding Communication: Shyness, Reticence, and Communication Apprehension.3rd edition. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Daly, John A., Anita L. Vangelisti, and Suzanne M. Daughton. 1987. The nature and correlates of conversational sensitivity. Human Communication Research 14: 167–202.

Edwards, Renee, James M. Honeycutt, and Kenneth S. Zagacki. 1988. The development of social cognitions: An investigation of imagined interaction. Western Journal of Communication 52: 23–45.

Friedrich, Gustav and Blaine Goss. 1984. Systematic desensitization. In John A. Daly and James C. McCroskey (eds.), Avoiding Communication: Shyness, Reticence, and Communcication Apprehension, 173–187. Beverly Hills, Calif.: Sage.

Freud, Sigmund. 1908. The relation of the poet to day-dreaming. In Philip Rieff (ed.), Character and Culture, 34–43. New York: Collier Books [1972].

Glaser, Stanley R. 1981. Oral communication apprehension and avoidance: The current status of treatment research. Communication Education 30: 321–341.

Gottman, John M. 1994. What Predicts Divorce? Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hamilton, Mark A., Ross W. Buck, Robert M. Chory, Michael J. Beatty and Linda A. Patrylak. 2009. Individualistic and cooperative affect systems as determinants of aggressive or collaborative message choice. In Michael J. Beatty, James C. McCroskey, and Kory Floyd (eds.), Biological Dimensions of Communication, 227–250. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press.

Hample, Dale and Judith M. Dallinger. 1995. A Lewinian perspective on taking conflict personally: Revision, refinement, and validation of the instrument. Communication Quarterly 43: 297– 319.

Hample, Dale, Adam S. Richards and Ling Na,. 2012. A test of the conflict linkage model in the context of serial arguments. Western Journal of Communication 76: 459–479.

Honeycutt, James M. 1989. A pilot analysis of imagined interaction accounts in the elderly. In Ronald Marks and Julianna Padgett (eds.), Louisiana: Health and the Elderly, 183–201. New Orleans, LA: Pan American Life Center.

Honeycutt, James M. 1995. Imagined interactions, recurrent conflict and thought about personal relationships: A memory structure approach. In J. Aitken and L. J. Shedletsky (Eds.), Intra personal Communication Processes, 138–151. Plymouth, MI: Midnight Oil and National Communication Association.

Honeycutt, James M. 2003. Imagined Interactions: Daydreaming about Communication. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Honeycutt, James M. 2004. Imagined interaction conflict-linkage theory: Explaining the persistence and resolution of interpersonal conflict in everyday life. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 23: 3–25.

Honeycutt, James M. 2006. Enhancing EI intervention through imagined interactions. Issues and Recent Developments in Emotional Intelligence, [On-line serial], 1(1), 1–4.

Honeycutt, James M. 2008. Imagined Interaction Theory: Mental Representations of Interpersonal Communication. In L. A. Baxter and D. Braithwaite (eds.). Engaging Theories in Interpersonal Communication, 77–87. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Honeycutt, James M. 2008–2009. Symbolic interdependence, imagined interaction, and relationship quality. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 28: 303–320.

Honeycutt, James M. 2010a. Introduction to Imagined Interactions. In James M. Honeycutt (ed.), Imagine that: Studies in Imagined Interaction, 1–14. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Honeycutt, James M. 2010b. Dialogue Theory and Imagined Interactions. In James M. Honeycutt (Ed.), Imagine that: Studies in Imagined Interaction, 195–206.

Cresskill, NJ: Hampton. Honeycutt, James M. 2010c. Forgive but don’t Forget: Correlates of Rumination About Conflict. In James M. Honeycutt (Ed.), Imagine that: Studies in Imagined Interaction, 17–29. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Honeycutt, James M. 2010d. Physiology and Imagined Interactions, In James M. Honeycutt (ed.), Imagine that: Studies in Imagined Interaction, 43–64. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton.

Honeycutt, James M. and Suzette P. Bryan. 2011. Scripts and Communication for Relationships. New York: Peter Lang.

Honeycutt, James M., Charles W. Choi and Randy D. Deberry. 2009. Communication apprehension and imagined interactions. Communication Research Reports 26: 228–236.

Honeycutt, James M., Renee Edwards and Kenneth S. Zagacki 1989–1990. Using imagined interaction features to predict measures of self-awareness: Loneliness, locus of control, self-dominance, and emotional intensity. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 9: 17–31.

Honeycutt, James M. and Sherry G. Ford. 2001. Mental imagery and intrapersonal communication: A review of research on imagined interactions (IIs) and current developments. In William B. Gudykunst (ed.), Communication Yearbook 25: 315–345. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Honeycutt, James M. and Shaughan A. Keaton. 2012–2013. Imagined interactions and personality preferences as predictors of relationship quality. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 32: 3–21.

Honeycutt, James M., Christopher Mapp, Khaled A. Knasser and Joyceia M. Banner. 2009. Intrapersonal communication and imagined interactions. In Michael B. Salwen and Donald W. Stacks (eds.) An Integrated Approach to Communication Theory and Research, 323–335. NY: Routledge.

Honeycutt, James Michelle E. Pence and Christopher C. Gearhart. 2012–2013. Associations between Imagined Interactions and the “Big Five” Personality Traits. Imagination, Cognition, and Personality 32: 273–289

Honeycutt, James M. and John M. Wiemann. 1999. Analysis of functions of talk and reports of imagined interactions (IIs) during engagement and marriage. Human Communication Research 25: 399–419.

Honeycutt, James M., Kenneth S. Zagacki and Renee Edwards. 1992–1993. Imagined interaction, conversational sensitivity and communication competence. Imagination Cognition, and Personality 12: 139–157.

John, Oliver P., Eileen M. Donahue, and Robert L. Kentle. 1991. The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley, CA: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Johnson, Kristen L. and Michael E. Roloff. 1998. Serial arguing and relational quality: Determinants and consequences of perceived resolvability. Communication Research 25: 327–343.

Malis, Rachel S., and Michael E. Roloff. 2006. Demand/withdraw patterns in serial arguments: Implications for well-being. Human Communication Research 32: 198–216.

McCann, Robert M., and James M. Honeycutt. 2006. A cross-cultural analysis of imagined interaction. Human Communication Research 32: 274–301.

McCroskey, James C. 1977. Oral Communication apprehension: A summary of recent theory and research. Human Communication Research 4: 78–96.

McCullough, Michael E., C. Garth Bellah, Shelley D. Kilpatrick and Judith L. Johnson. 2001. Vengefulness: Relationships with forgiveness, rumination, well-being, and the Big Five. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 27: 601–610.

McCullough, Michael E., Giacomo Bono and Lindsey M. Root. 2007. Rumination, emotion, and forgiveness: Three longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 92: 490–505.

Meyer, Janet R. 1997. Cognitive influences on the ability to address interaction goals. In J. O. Greene (Ed.), Message Production: Advances in Communication Theory, 71–90. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Nickel, Peter and Friedhelm Nachreiner. 2003. Sensitivity and Diagnosticity of the 0.1-Hz Component of Heart Rate Variability as an Indicator of Mental Workload. Human Factors 45: 575–590.

Nolen-Hoeksema, Susan. 1991. Responses to depression and their effects on the duration of depressive episodes. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 100: 569–582.

O’Brien, Tess B. and Antia DeLongis. 1996. The interactional context of problem-; emotion-; and relationship-focused coping: The role of the Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality 64: 775–813.

Opt, Susan K. and Donald A. Loffredo. 2000. Rethinking communication apprehension: A Myers-Briggs perspective. Journal of Psychology 134: 556–570.

Porges Stephen W. 2011. The Polyvagal Theory: Neurophysiological Foundations of Emotions, Attachment, Communication, and Self-Regulation. New York: Norton.

Richmond, Virginia and James C. McCroskey. 1998. Communication: Apprehension, Avoidance, and Effectiveness, 5th edition. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Robson, Colin. 2002. Real World Research. A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers (Second Edition). Malden: Blackwell.

Roloff, Michael E. and Rachel M. Reznik. 2008. Communication during serial arguments: Connections with individuals’ mental and physical well-being. In Michael T. Motley (ed.), Studies in Applied Interpersonal Communication, 97–120. Los Angeles CA: Sage.

Ruesch, James and Gregory Bateson. 1951. Communication: The Social Matrix of Psychiatry. New York: W. W. Norton and Company.

Sapolsky, Robert M. 1998. The Trouble with Testosterone and Other Essays on the Biology of the Human Predicament. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Swickert, Rhonda and Taylor Owens. 2010. The interaction between neuroticism and gender influences the perceived ability of social support. Personality and Individual Differences 48: 385–390.

Wallenfelsz, Kelly P. and Dale Hample. 2010. The role of taking conflict personally in imagined interactions about conflict. Southern Communication Journal 75: 471–487.

Wish, Myron, Michael Deutsch, and Susan J. Kaplan. 1976. Perceived dimensions of interpersonal relations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 33: 404–420.

Zammitto, John H. 2004. A Nice Derangement of Epistemes. Post-positivism in the study of Science from Quine to Latour. Chicago & London: The University of Chicago Press.