CHAPTER 3

Behavioral Economics, Thinking Processes, Decision Making, and Investment Behavior

INTRODUCTION

According to traditional economic theory embodied in the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), investor behavior should be rational in terms of incorporating all relevant information into the decision-making process, as well as being calculating, forward looking, and not subject to regret. Such behavior also is ideally bereft of emotions because emotions are assumed to bias decisions away from calculating, forward-looking, and maximizing outcomes. In other words, traditional economics assumes decisions result in optimal financial outcomes. What it assumes to be rational behavior should generate the highest possible returns compared to less rational or irrational behavior. Moreover, rational investor outcomes should be efficient such that, on average, market prices reflect the fundamentals of investment choices and therefore incorporate all relevant information about investment prospects.

This chapter addresses the empirical reality that investor behavior often does not generate outcomes that are efficient, yielding suboptimal financial returns, and market prices often deviate from their fundamental values (e.g., resulting in bubbles and busts) (Shiller 2000). Moreover, the evidence indicates that the returns of active market traders or investors are typically below those generated by passive (or systematic) investors (Malkiel 1973, 2003). This suggests that active decision-making strategies, using modern knowledge technology, including sophisticated financial data gathering and analyses typically do not beat less calculating behavior that relies on decision-making shortcuts. Thus, what many would deem to be more rational behavior often generates subpar economic and financial outcomes.

This chapter examines the contradictions between empirical reality and traditional economic theory through the lenses of behavioral economics. Behavioral economists and behavioral finance researchers play an important role in identifying these various mismatches between reality and theory. Many behavioral economists contend that individuals are characterized by large and persistent biases when making decisions, often driven by the leading role that emotions and heuristics (mental shortcuts or mistakes) play in the decision-making process (Tversky and Kahneman 1974; Kahneman and Tversky 1979, 2000; Kahneman 2003, 2011; Altman 2004, 2010b, 2012b; Shefrin 2007; Thaler and Sustein 2008). These biases result in decisions and outcomes that differ from the predictions of traditional economic wisdom, given its prior assumptions about what constitutes rational choice behavior.

Behavioral economics, rooted in the bounded rationality approach developed by Simon (1955, 1978, 1987) and March (1978), who were early pioneers of behavioral economics, also find that real world decision making generates choices and outcomes that deviate from the predictions of the traditional economic wisdom. But from this perspective, the decision-making heuristics are rational given the decision constraints faced by the individual and often generate superior outcomes than what would arise from adopting traditional economic decision-making norms. Errors in decision making can be corrected by improving the decision-making environment (incorporating informational and incentive variables) and through learning (Smith 2003; Gigerenzer 2007).

BEHAVIORAL ECONOMICS, HEURISTICS, AND DECISION MAKING

From the perspective of behavioral economics, both the limited and unique processing capacity of the human brain and the decision-making environment influence decision makers. People adopt ways to decide and choose that differ from how they would behave under the behavioral and institutional assumptions of traditional economics. For instance, many behavioral economists assume that individuals or organizations adopting non-conventional approaches to decision making, rooted in real world decision-making parameters, make rational or smart decisions. This would be the case for household decision makers, management, and investors (March 1978).

Simon (1978, 1987) developed the concepts of bounded rationality and satisficing to encapsulate smart decision-making processes that smart human decision makers develop, adapt, and adopt. Some view this approach as part of an alternative theoretical decision-making framework to the conventional concepts of pure rationality of narrowly calculating and materially maximizing individuals. A boundedly rational satisficing individual does the best she can, given her physiological, psychological, and institutional decision-making parameters. Simon (1987, p. 267) defines bounded rationality as “rational choice that takes into account the cognitive limitations of the decision-maker—limitations of both knowledge and computational capacity. Bounded rationality . . . is deeply concerned with the ways in which the actual decision-making process influences the decisions that are reached.”

Boundedly rational individuals can make errors in their decisions, but these are often correctable through learning and experience. Moreover, institutional change can reduce the extent of errors in decision making. This approach does not focus on possible biases or persistent errors in decision making. Following this approach, researchers offer arguments and evidence on boundedly rational behavior that often produce superior results (Smith 2003; Gigerenzer 2007; Altman 2012a, 2012b).

Todd and Gigerenzer (2003) and Gigerenzer (2007) refer to decision-making shortcuts that are satisficing by nature as fast and frugal heuristics. Such heuristics might be largely intuitive or more deliberative in nature. Kahneman (2011) calls the former fast thinking and the latter slow thinking. A key argument here is that individuals learn through education and experience as well as from others and develop methods of arriving at decisions that are best practice. These decision-making heuristics evolve over time (Hayek 1945). They develop through experience and learned behavior based on knowledge of best-practice decision-making behavior developed in one's family or community. Some refer to such evolved decision-making behavior as evolutionary rationality (Smith 2003; Gigerenzer 2007).

Fast and frugal heuristics are similar to the affect heuristic. It represents a decision-making shortcut that is quick and relatively easy and is typically predicated on intuition and influenced by emotional considerations. This reduces the cost of search and information processing. Given bounded rationality, efforts to reduce decision-making costs are eminently intelligent. However, the affect heuristic can result in errors in decision making or in superior decisions depending on the circumstance.

Although biases and persistent errors, often called irrational behavior, are not the mainstay of the boundedly rational approach, they are critical to the Kahneman-Tversky perspective. Here errors are all too often a product of cognitive biases, which persist over time with little or no substantive Bayesian updating taking place (i.e., individuals do not update their mental models with new and relevant information). Emotions, which are part of the human decision-making mechanism, play a vital role in generating errors and biases in decision making (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Kahneman 2003). In the errors and biases approach, even if no limitations exist to an individual's information gathering and processing capacity, the average individual would not behave in the fashion prescribed and predicted by the conventional wisdom because of the introduction of emotional considerations. Emotions would generate errors and biases in decision making.

Recognizing the importance of emotions to decision making is critical to Kahneman and Tversky's development of prospect theory. It represents an alternative to subjective expected utility theory as a means of better understanding and describing decision making under uncertainty (Altman 2010b). Emotions and intuition inform decision-making heuristics, often resulting in suboptimal results (biases and errors) from an individual's long-term perspective.

INVESTMENT HEURISTICS AND INVESTING IN FINANCIAL ASSETS

Investors use various decision-making shortcuts or heuristics to save time and money in a world of uncertainty. Much of this uncertainty is immeasurable in contrast to risk, where probabilities of future events can be determined and assigned (Knight 1921). Using heuristics yields outcomes that often differ from what conventional wisdom predicts. Key questions are whether these heuristics are smart or rational from an individual and social perspective and whether these heuristics can be improved. To introduce some key decision-making variables most pertinent to investors, a good starting point is to provide a narrative on investor decision making in financial markets.

The manner in which individuals tend to invest in financial assets helps illustrate why and the extent to which individuals do not conform to traditional economics (i.e., neoclassical rational behavior) and how this affects economic outcomes. It also helps clarify the distinction between different approaches to behavioral economics and between such approaches and the traditional economic wisdom. Traditional finance's EMH maintains that not only should asset prices reflect the underlying fundamental values of the assets, incorporating all pertinent information, but also that no individual can predict future movements in asset prices because these prices follow a random walk. This is known as the random walk hypothesis, articulated in Malkiel (1973) and developed by Fama (1965). In terms of normative behavior, conventional wisdom holds that individuals should follow neoclassical behavior for market efficiency to prevail.

The EMH has three components. One relates to the notion that one cannot consistently predict short-term movements in asset prices. Another assumes that market prices reflect the fundamental value of assets. The third assumes that neoclassical behavior generates optimal financial results.

The evidence does not support the hypothesis that conventional behavioral norms yield optimal results. For example, passive investment (non-super-calculating) strategies typically yield higher returns than more aggressive calculating active approaches. If public policy succeeds in converting passive to active (super-calculating) traders or in hiring the services of active traders, the evidence suggests that such individuals would be worse off financially. Passive investment being superior in terms of outcomes is consistent with the EMH, but not with the normative behavioral perspective of the traditional economic wisdom or with the errors and biases approach to behavioral economics. All that is required for passive investment to be a superior decision-making heuristic is that one cannot predict day-to-day movements in stock and related prices (Thaler 2009).

Wärneryd (2001) concludes that passive investors are typically more successful than the relatively more neoclassical (super-calculating) oriented sophisticated investors. Passive investors hold on to their financial assets over the long term with only marginal adjustments in the short run. They make no effort to engage in active market analysis in an effort to beat the market. Passive traders apply the decision-making heuristic of buying and holding representative shares in, for example, the Standard & Poor's 500 index. This strategy is referred to as indexing. The objective is to replicate the returns of such a target fund. Passive investors do not try to beat the index's rate of return and remain passive when facing market volatility. This riding-the-wave heuristic does significantly better than actively engaging in intensive calculating behavior.

Gigerenzer (2007) finds that passive investing strategies are both rational and efficient. He uses the investment behavior of Harry Markowitz to exemplify his case. Markowitz (1952) developed a mathematical formulation to determine the structure of a rate of return maximizing asset portfolio, given an individual's risk preference. He uses what Gigerenzer refers to as the 1/N rule, wherein available investment funds are equally dispersed across each of the designated N funds. This is a form of passive investment, which is a type of satisficing behavior. This satisficing approach outperforms, net of investment fees, investment portfolios constructed using the optimal algorithms derived from economic theory, except over very long spans of time. For example, 50 assets distributed using the complex algorithm require 500 years to outperform the 1/N rule asset distribution. Passive-based portfolios typically outperform investment portfolios designed by major investment houses and fund managers using active investment strategies (Malkiel 2003). Although active investment strategies sometimes outperform passive, satisficing strategies, these successes do not persist over time and are largely idiosyncratic and consistent with a random walk. Active strategies might achieve superior returns based on superior heuristics, but the typical individual in a world of asymmetric information would have difficulty distinguishing the active investors whose superior results are idiosyncratic from those who results are time consistent.

Overall, passive investment strategies, exemplified by the 1/N heuristic, is a fast and frugal decision-making heuristic that is consistent with the computational capacities of the human brain working within the realm of imperfect and asymmetric information as well as uncertainty. Passive investment strategies also minimize emotional drivers to decision making, which often motivate and determine individuals' investment decisions and can generate errors in decision making. With passive strategies, individuals will not, for example, engage in herding behavior, which is one cause of severe bubbles and busts in asset prices. The passive investor maintains a default investment strategy irrespective of movements in asset prices.

An important caveat exists to this argument. Many individuals or groups of individuals who invest in active-led investment financial portfolios do so passively. They do not intentionally choose an active strategy. Given imperfect, asymmetric, and even incorrect information, they often follow passive strategies to select who will manage their funds. But they do so without necessarily knowing the details of how their funds will be managed or even the difference between passive and active investment strategies. Nor do they necessarily have true knowledge about the expected present discounted value of the returns of a fund managed using a passive versus an active investment strategy. But using passive heuristics to choose investment funds can be rational given a world of bounded rationality. Nonetheless, investors might end up holding a fund that they would have preferred not owning if they had better information and understood the risk-return differences among various funds.

The passive investment heuristic is not the preferred option of most investors who are intent on beating the market. Owners and managers as investors differ from individuals who are investing their money in financial assets but are not fund owners and managers. These are more akin to consumers of financial assets. These investor-consumers typically adopt passive strategies using fast and frugal heuristics. What the preferred investment strategy is for the consumer-investors is unclear because their choices are not based on whether a fund is managed passively or actively. The passive heuristic does a better job describing the behavior of consumer investors than the choices made by investors in general.

For many behavioral economists and economic psychologists, the passive investment strategy of investing in a relatively diversified asset portfolio (such as is given by the 1/N rule) is the optimal heuristic for investor behavior. This assumes that investors are not privy to insider information. Of critical importance is that the active investing behavioral norm (the neoclassical heuristic) tends to result in suboptimal returns. Many investors adopt neoclassical behavioral norms despite the fact that passive investment strategies achieve superior returns. This raises the question: Why would rational individuals adopt investment strategies that are objectively known to yield inferior returns?

The reality of passive investment strategies outperforming active strategies is consistent with the bounded rationality approach to behavioral economics but it is inconsistent with neoclassical economics decision-making norms. However, the superiority of passive strategies is consistent with the hypothesis put forth by Kahneman (2003, 2011) that choices determined by emotional considerations can be error-prone and result in suboptimal decision making. Overall, behavioral economics helps explain why individuals make investment choices that are inconsistent with neoclassical predictions; why fast and frugal heuristics can generate superior financial results; and why some individuals make choices that produce suboptimal economic returns.

THE TRUST HEURISTIC AND DECISION MAKING

The trust heuristic is a nonconventional tool used by decision makers who might engage in irrational or error prone and biased behavior. This heuristic is part of the fast and frugal heuristic toolbox. Like many such heuristics, emotional and intuitive variables affect the trust heuristic. Trust has been part the human decision-making toolbox for a millennium. In the absence of legal guarantees for enforcing contracts, the trust heuristic becomes a substitute for such legal guarantees. It also lowers the transaction costs of engaging in contractual arrangements and buying goods and services, even when legal guarantees and redress are in place (Greif 1989; Landa 1994; Kohn 2008).

Trust is the high probability expectation that the other party to a transaction will deliver on promises made. The reputation of the other party often serves as the basis for trust. Trust-based transactions are often enforced through the negative reputational effect when reneging on a transaction or a relationship and the positive effect when holding true to a contract or a relationship. The reputational effect carries with it economic consequences. Over time, being trustworthy becomes a social norm and evolves into intuitive forms of behavior. Legal and informal sanctions and economic rewards encourage trust. Investors frequently use the trust heuristic as the most effective and efficient way to execute transactions.

When employing the trust heuristic, decision makers locate proxies for the trustworthiness for detailed, complex, and reliable information that cannot be accessed either at all or only at substantial economic and time costs. Among these proxies are the rating agencies of financial assets, government sanction of financial assets, expert opinion, and ethnic, neighborhood, religious, and racial groupings one identifies with or trusts. For example, if Standard & Poor's assigns a triple-A rating to particular financial asset, individuals and financial organizations are likely to trust that such a rating is reliable.

Individuals will invest with family, friends, and members of their community or religious group because they believe that these individuals can be trusted. This type of trust can be enforced if one believes that if the bonds of trust are broken the party in question will suffer reputational and/or economic costs. Moreover, individuals often follow the leaders whom they trust and engage in herding behavior when they are unsure about what product or financial asset to buy or sell. Herding can result in market inefficiencies called price cascades or asset price bubbles that can be severe, especially when based on misleading information. Investors often assume that portfolio managers are relatively better informed in a world of complex and often misleading information.

Although the trust heuristic is not part of the traditional economics toolbox, it provides an efficient decision-making tool that appears to achieve economic results that are often superior to those obtained when relying on conventional search and information gathering processing decision-making tools. It is also often more efficient and effective than relying on formal and detailed contracts. Thus, the trust heuristic is a form of rational or boundedly rational or smart behavior. However, the effectiveness and efficiency of the trust heuristic is a function of the extent to which trustworthiness and reciprocity in trust-based transactions have become part of one's community and society's social norms. It is also a function of the extent to which both proxies for trustworthiness can be trusted and decision makers have accurate and reliable information with which to make decisions. If someone makes a decision on the basis of false information that is believed to be true, this decision is not the individual's preferred decision and does not reflect her true preferences (Altman 2010b).

The trust heuristic results in a market failure in a world of false and deceptive information. This would be the case when individuals invest in triple-A rated assets when in fact the assets should be rated A or below. This would also be true when an individual invests in funds that she believe to be legitimate and whose rate of return and risk information are accurate and reliable. The Madoff Ponzi fund is a good example of individuals investing in a fund they falsely believed to be legitimate and subject to government regulatory scrutiny. People decide intuitively given the trust proxies and related signals at hand. Hence, this illustrates the importance of the trustworthiness of trust proxies for the efficiency of the trust heuristic.

Institutional design positively affects the efficiency of the trust heuristic and increases the probability that information to investors is reliable and accurate (i.e., trustworthy). This reduces the chances that consumer-investors and investors make choices on prospects that are inconsistent with their preferences. Although this does not preclude errors in decision making, it does reduce the probability of making errors. Also, enhancing the capacity of decision makers to understand the relevant information and presenting information in a relatively easily understandable format (known as financial literacy) also contributes to reducing the extent of decision-making errors. Such institutional design often involves government intervention in certifying and rating financial information, investment funds, and fund managers (Altman 2012a).

OTHER CRITICAL DECISION-MAKING HEURISTICS

Behavioral economists have identified other heuristics important to investor decision making. Some view these as generating errors and biases in decision making. Others arguably produce superior financial results. These heuristics, whether they result in optimal or best possible economic results, characterize the decision-making behavior of real world investors. One important determinant of the heuristics adopted is that immeasurable forms of risk, sometimes referred to as uncertainty, frequently characterize decision-making environments.

Knightian Uncertainty versus Risk

Behavioral economics views uncertainty where outcomes can be projected based on assigned probabilities (expected values) and also when uncertainty is such that expected outcomes cannot easily be predicted. Much of contemporary behavioral economics focuses on how humans would behave when probabilities are easily assigned to outcomes and when expected values can be computed with relative ease. However, the decision-making environment is also of considerable importance where investors cannot easily determine expected values.

Knightian uncertainty is uncertainty that cannot be measured with any precision. Risk can be measured in terms of probabilistic outcomes, based on past parameters and outcomes. Although contemporary economics focuses on risk, Knight (1921) considers uncertainty to be critical to substantive economic analysis. Although risk is important, uncertainty is often more so. Rational individuals can be expected to behave differently when faced with risk as compared to uncertainty.

Animal Spirits

Animal spirits, also called irrational exuberance, is an important driver of investment behavior (Shiller 2000; Akerlof and Shiller 2009; Farmer 2010). In traditional economic modeling, animal spirits do not affect investor behavior. But animal spirits are certainly a fast and frugal heuristic that characterizes much investor decision making. They are highly intuitive and involve trusting one's gut instincts, which are often experientially based, as well as the gut instincts of others. In contemporary behavioral economics, animal spirits are often a source of error and bias in decision making, which can result in manias, panics, and eventually crashes in asset markets, with large repercussions for the rest of the economy. For Keynes (1936), animal spirits are much more than this. They characterize much of investor and consumer behavior and need to be integrated into the modeling of the economic decision making.

Keynes (1936) refers to animal spirits as behavior that is motivated by emotive factors, as opposed to calculating or hard-core economic rationality demanded by traditional economics. Keynes (pp. 161−162) speculates that decisions “can only be taken as the result of animal spirits—a spontaneous urge to action rather than inaction, and not as the outcome of a weighted average of quantitative benefits multiplied by quantitative probabilities.”

Although animal spirits are not calculating behavior, they are based on a sense of what one expects to occur in the near future and a heuristic based on one's expectations in a world of uncertainty. Animal spirits are informed by the information that an individual has at hand and by the behavior of others whom one believes or trusts have a better understanding of market movements and outcomes than oneself. Animal spirits would be most important when uncertainty is Knightian (incalculable), but also when risks are calculable in terms of assigned probabilities to outcomes.

Regarding animal spirits in general, government and central bank pronouncements can affect a person's beliefs about movements in future asset prices, as can the news and statements by preeminent and respected individuals. A key point in favor of introducing animal spirits as a variable in modeling decision making is that price movements such as interest rates and changes in income are not the only important variables determining behavior. Non-economic variables, especially psychological variables, embodied in the concept of animal spirits, are also of overriding importance. Even if interest rates are very low, individuals might not increase spending on financial assets and housing stocks (e.g., if animal spirits are depressed). Here the elasticity of demand relative to changes in interest rates is at or near zero. Keynes refers to this as the liquidity trap. The same elasticity of demand would be expected relative to price changes for a large set of marketed products given a depressed state of animal spirits.

The animal spirits heuristic is consistent with bounded rationality and satisficing. Using this heuristic is smart behavior given the constraints facing the individual. Nevertheless, animal spirits can serve to generate large deviations from economic fundamentals. This is especially true when information is false or misleading and public pronouncements of experts dampen or heighten the state of animal spirits, incentivizing decision makers to make economic choices that help create manias and panics and, hence, avoidable economic crisis. Methods of reducing such deviations involve improving the quality of information and having government recognize the importance of public pronouncements on the economy for decision making in the financial markets and the real economy. Recognizing the importance of animal spirits leads to improved modeling of decision making and to increased efficiency of public policy and institutional design.

Beauty Contest

The concept of a “beauty contest,” developed by Keynes (1936), follows from the assumption of Knightian uncertainty. Decision makers do not know what the future might bring. In economics, a beauty contest refers to rational individuals estimating what future prices (the beauty) might be by anticipating what other people believe future prices (the most beautiful) will be, as opposed to what the fundamental value (true beauty) of the assets actually is. Such beliefs, if actualized, help determine the direction and movements in future prices (i.e., investor sentiment and momentum).

Assume that how other people behave or how one expects other people to behave in the market motivates animal spirits. In a world of uncertainty, investors use proxies such as rumors or insights from experts to build their expectations. These information flows provide insight on how other investors will behave. Such flows also provide information to the decision maker to make more intelligent investment decisions predicated on gut feeling. This is important to investors who engage in active investment strategies in a world of bounded rationality and Knightian uncertainty. However, such strategies have little to do with the fundamental values underlying the assets.

Herding

Herding occurs when decision makers follow the leader in terms, for example, of investment decisions. Herding is a very common evolved heuristic. It is particularly characteristic of investor behavior and is related to Keynes' model of beauty context behavior. Herding occurs in the face of bounded rationality and Knightian uncertainty. It occurs when investors are unsure how asset prices will move and trust in the wisdom of the crowds or the leader of the crowd. Herding behavior, if persistent, results in price cascades (i.e., when prices increases at an increasing rate) and, therefore, bubbles in asset prices. In other words, such behavior can result in manias, panics, and crashes. Better information about the assets being purchased, especially their true risk and the fundamental value of the asset, can moderate the extent of herding and price cascades. The extent that individuals expect to bear the economic burden of any panics and crashes that invariably follow manias in asset prices is also important. This requires minimizing the extent of moral hazard (i.e., when individ uals do not bear the full risk of their choices) that characterizes investor behavior.

Loss Aversion

According to Kahneman and Tversky (1979), individuals have a strong aversion to losses (loss aversion) when holding risk parameters constant. The authors maintain that people weigh losses about twice as much as gains, so that $100 gained does not neutralize $100 lost, which would be the case based on conventional wisdom. Based on loss aversion, in the previous example, a person's utility would be reduced substantially. An individual characterized by loss aversion would avoid options that might be characterized by losses even when the expected value of such options is positive. Individuals are willing to sacrifice income or wealth to mitigate prospective economic loses. Income and wealth maximization would not be the objective of loss-averse individuals.

Disposition Effect

The disposition effect results in individuals selling stocks too quickly that have appreciated in price, but holding on to stocks that have depreciated in price for too long. This is consistent with acknowledging gains but not losses. In this case, individuals will sell high too quickly to avoid possible losses (i.e., a decline in the value of a stock). They will resist selling stocks that are falling in value or a business losing money in an effort to avert losses, hoping that their investment will recover its value in time. Yet, the evidence suggests that in panics many individuals sell stocks that are falling in value too soon, precipitating market crashes.

Illusion of Control

An illusion of control occurs when decision makers believe they have some control over outcomes although they do not. These decision makers then proceed to design and adopt strategies that they believe will affect outcomes but which are determined either randomly or are outside of their control. The economic consequence of the illusion of control is that individuals subject to this illusion unnecessarily expend time, money, and mental energy trying to affect outcomes. A classic example of the illusion of control are gamblers who believe that they can consistently win fair bets by devising methods of gambling that objectively have no substantive effect on outcomes. Some contend that this would also be the case of amateur and even professional investors who believe that they can persistently outperform the market.

Overconfidence

Unlike the illusion of control, overconfidence pertains to scenarios in which decision makers can actually affect outcome. Overconfident individuals are those who subjectively believe that they can affect outcomes to a greater extent than they actually can. When this occurs they will invest in projects or overinvest because of overconfidence bias. When a person is 100 percent confident of her decision, this decision should be 100 percent correct ex post in terms of outcome (e.g., discounted net present value [NPV]). If a student believes that he will earn a grade of 90 on an exam and objectively can be expected to earn a grade of 60, this is another example of overconfidence bias. An overconfident investor will underestimate the risk of his investment and take greater risk than is wise. Such was the case with Long Term Capital Management, where its PhD-intensive financial management thought they were too smart to make poor and overly risky bets on the market, eventually requiring a $3.6 billion bailout orchestrated by the Federal Reserve. One source of overconfidence is ignoring sentiment-based risk (i.e., risk derived from decision makers acting on emotional considerations, which are often informed by the trust heuristic and herding).

Overconfidence bias is not confined to point estimates of prospective outcomes. It also refers to the subjective evaluation of confidence intervals around these point estimates. An individual might predict that he will earn a 30 percent rate of return on a prospect, but an overconfident individual ignores the probability of earning a negative rate of return. In this case, realizing a low probability but highly negative return could have severe economic consequences. This notion is related to what Taleb (2010) refers to as “black swan” events, which are very low probability events that, if they occur, can have major consequences.

Kahneman (2011) maintains that an important factor responsible for overconfidence is the illusion of validity. He contends that individuals tend to construct consistent narratives that confirm their prior beliefs. Developing such narratives that provide additional but irrelevant information for predictive purposes also tends to confirm individuals in their prior beliefs. If a narrative is inconsistent, this can motivate individuals to assume that an event is highly improbable when based on objective criteria. One example that follows from Kahneman relates to grades earned by students. One student has a mix of A and B grades (incoherent) and another has straight As (coherent). Some individuals assume that the straight A student is most likely to succeed. But objectively speaking, this is not the case. In the case of an investor, if one can tell a coherent story, for example as done by Bernard Madoff, his profile is that of a successful investor. Thus, consumer-investors assumed that Madoff was a successful investor without consulting more pertinent information. Many investors with coherent narratives are failures as investors including Madoff and Long Term Capital Management. A key supplementary assumption of the illusion of validity is that individuals will systematically ignore contrary evidence given the coherence of a particular narrative. This overlaps with confirmation bias as later discussed. Under the illusion of validity, individuals use inappropriate mental models to engage the decision-making process.

Overoptimism

Overoptimism occurs when an individual believes that he or she is less at risk or more likely to achieve a certain rate of return or outcome than is objectively true. An overly optimistic investor believes that he or she is less likely to fail or is more likely to succeed than another individual, even if no clear and unequivocal objective basis exists for this belief.

Overoptimism can be independent of overconfidence. Overconfidence is specific to an individual's subjective and exaggerated perception of his or her capabilities relative to objective standards. Overconfidence and overoptimism are related in that both overoptimistic and overconfident individuals tend to take excessive risks relative to what they would take if their perceptions of risks and reward were more aligned with objective analyses.

Overconfidence and Overoptimism

Both overconfidence and overoptimism characterize many investors. This would be expected in a world of bounded rationality and Knightian uncertainty, assuming a random distribution of preferences for overconfidence and overoptimism. Such individuals may make decisions that may be materially damaging to themselves and others. Determining the extent to which this negative spillover is a function of an incentive environment that facilitates or encourages moral hazard is important to determine. In other words, decision makers can engage in what appears to be overconfident and overoptimistic behavior if they believe that they will not be responsible for the downside of their relatively risky decisions.

Another issue related to both overconfidence and overoptimism is whether such behavioral preferences are necessarily bad for the economy. That is, does some optimal level of overconfidence and overoptimism exist that is good for the individual and the economy? Overconfidence and overoptimism appear to be critical characteristics of entrepreneurship when decision makers cannot predict with any substantial degree of confidence what the outcomes of particular decisions might be. Both entrepreneurs and investors in financial markets take Knightian risks, whereas non-entrepreneurial types have a strong predisposition toward certain outcomes. Individuals characterized by uncertainty avoidance would not be entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship is crucial to vibrant market economies. Such Knightian decision makers believe that they will succeed where their competitors will fail or not do as well.

Many behavioral economists note that overconfidence and overoptimism are not necessarily suboptimal from a societal perspective but rather that excessive overconfidence and overoptimism tend to produce suboptimal economic results. Moreover, excessive overconfidence and overoptimism are more likely to occur when individuals make decisions independently of others, which facilitate the prevalence of the conformation bias and limit the extent of relevant information available to the decision maker. One method of reducing the extent of excessive overconfidence and overoptimism is for one individual's decisions to be informed by other decision makers or advisors in an open-minded decision-making environment. This would avoid the possible negative spillovers from excessive overconfidence and overoptimism.

In the errors and biases approach, excessive overconfidence and overoptimism are assumed to overwhelm loss avoidance. Another approach is that loss avoidance does not characterize all individuals. Those individuals characterized by excessive overconfidence and overoptimism in the economic domain might be neoclassical in their preferences about losses and gains. This would be particularly true of entrepreneurs.

Overoptimism and overconfidence are related to the illusion of certainty, where an individual believes that something is true even though objectively it might not be. It is also related to hindsight bias, where individuals believe that given the occurrence of an event, they are responsible for it. This is a form of spurious correlation. The fact that a person's past actions are highly correlated with current positive outcomes does not necessarily mean that the individual's past decisions were responsible for current outcomes. This is synonymous with the illusion of control, where a person believes that he has control over outcomes that might occur for random reasons or for reasons unrelated to his behavior. A close connection exists between the illusion of certainty and hindsight bias.

Also related to both overoptimism and overconfidence is confirmation bias. Individuals ignore information or other people who challenge their prior hypotheses. Instead, they focus their attention on information and people such as advisors who confirm their prior hypotheses. Such contrary information and people can be dismissed as not being pertinent to their unique situation.

Also pertinent to overoptimism and overconfidence is representativeness bias. People believe that past returns or events are indicative or representative of future returns or events, ignoring the probabilistic nature of future outcomes. This is related to the recency bias where individuals evaluate economic and financial performance based on the most recent results. In this case, decision makers ignore past events, such as historical market downturns, and assume that the more recent events, such as the upside of asset bubbles, are representative of what one should expect in the future. Although many behavioral economists give the impression that these various biases and illusions are a general human characteristic, they might simply characterize a subset of human decision makers.

Lack of Bayesian Updating

One argument put forth by the errors and biases school in behavioral economics is the persistent lack of updating preferences, decisions, and choices based on new and better information sets. If this were the case, individuals could not and would not learn. Evidence suggests, however, that individuals tend to engage in Bayesian updating. So, in one-shot games, decision makers can make mistakes. But with experience, individuals tend to correct the errors of their ways as long as they have adequate incentives to do so. Bayesian updating over time is consistent with the bounded rationality approach to behavioral economics.

Ambiguity Aversion

Ambiguity aversion occurs when an individual avoids prospects where the outcome is ambiguous (i.e., less information and certainty about ambiguous outcomes exist) and favors more certain outcomes. This is the case even if the expected value of the ambiguous prospect is greater than the present value of the more certain prospect. Some refer to ambiguity aversion as a cognitive bias, although it is actually a by-product of imperfect information and Knightian uncertainty. Given these environmental constraints, the expected value cannot be easily determined and a large band or high variance exists around the point estimate, which is the expected value. The issue is not whether ambiguity-averse individuals do not want to increase their income or wealth. Rather, in any income or wealth maximizing exercise, individuals can be expected to choose the prospect with the less ambiguous outcome. Different individuals can be expected to be characterized by different levels of ambiguity aversion.

Winner's Curse

Some evidence indicates that in auctions and initial stock offerings, investors pay more than the intrinsic value of these options (Thaler 1988; Kagel and Levin 2002). So, if exploration rights to an oil field are auctioned off and this property has an expected present value of $1 billion, the winning bid would be $1.2 billion. The winner is cursed by winning a prospect that either generates financial losses or generates gains that are less than expected. The winner is cursed by overvaluing the intrinsic value of the prospect for which they bid. Although the winner's curse is most prevalent for bidders who are least experienced and poorly informed, it often persists even for experienced investors when faced with many bidders. More competition can result in suboptimal outcomes even for the more experienced and informed investors (a winner's curse). Also, the probability of the being cursed by a winning bid increases with the uncertainty of outcomes. In such situations, experience matters. But individuals continue to bid in auctions even when they know that the winner might be cursed. One way to minimize the probability and extent of a winner's curse is to design auctions such that the second highest bid wins (second-price auction) or introduce Vickrey auctions where the highest bid wins, but the winner only pays the value of the second highest bid.

RATIONAL INVESTOR DECISION MAKING IN A WORLD OF COMPLEX INFORMATION

The errors and biases approach to investor behavior focuses on systematic errors and biases in decision making. In contrast, the bounded rationality approach pays at least as much attention to the decision-making environment, which is assumed to have a critically important effect on decision making. Errors and biases can be a product of this environment as opposed inherent cognitive illusions. Posner (2009) provides an example of this. He contends, as do Lewis (2010) and Roubini and Mihm (2010), that a major cause of the severity of the 2008−2009 financial crisis was the incentive environment that evolved over the prior two decades. This decision-making environment, which was also a by-product of financial market deregulation, reduced the cost to rational individuals and large financial corporations of knowingly engaging in very high-risk behavior. Individuals were protected from downside risks while benefiting from the success of risky bets. This created a classic moral hazard environment that eventually resulted in catastrophic damage to financial markets and to the real economy because markets never internalized the negative externalities. This institutional failure was a product of the belief that individuals will self-regulate, fearing the negative reputational effects of poor decisions. This did not occur. Given, for example, a predisposition toward overconfidence and overoptimism by investors, an appropriately designed decision-making environment could minimize the extent of socially suboptimal economic decisions. Overconfidence and overoptimism need not generate severe booms and consequent busts.

Apart from incentives, the state of information is important to the decision-making environment. Misleading information and information that is difficult to understand or locate can contribute to errors in decision making, given the incentive environment, even in the absence of relevant cognitive biases. For example, informational failures can generate serious and avoidable errors in decision making. Such failures can occur if stocks are inappropriately rated, if individuals falsely believe that funds are properly regulated, if information is framed in a misleading manner, and if managers do not understand the theoretical basis (often scripted in sophisticated mathematical language) for their companies' decisions.

Shiller (2009, 2010) contends that an impartial body, such as a government agency, should be responsible for the provision of quality information. This is akin to the regulation and provision of product labels for foods and certificates of cleanliness earned by restaurants. Without high quality information, rational individuals will most likely make choices that they will regret. This is a form of avoidable market failure. Trustworthy information will increase the probability that individuals will not invest in assets that have higher risks than they can tolerate.

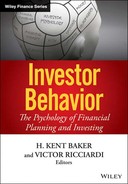

Exhibits 3.1 and 3.2 illustrate some of these arguments. Exhibit 3.1 highlights some main distinctions between the different approaches to behavioral and traditional economics regarding decision making. The errors and biases approach uses the neoclassical benchmark to measure the efficiency of decision-making processes and outcomes. The neoclassical production possibility frontier (PPF) given by (ac) is regarded as optimal, whereas the actual PPF (fg) is assumed to be achieved using heuristics. The gap between (ab) and (fg) is a function of persistent errors and biases in decision making. In the bounded rationality approach, neoclassical decision making yields a PPF of (cd) in Exhibit 3.1, whereas heuristics typically result in a PPF analogous to the thick PPF of (mstn). If the actual outcome is given by PPF (st) or (fg), there might be correctable errors in decision making. The actual outcomes need not be optimal or the best possible given constraints. The possibility for error as well as room for improvement in decision-making processes and environment always exists in the bounded rationality approach.

Exhibit 3.1 Errors and Biases and Bounded Rationality Perspectives

Note The errors and biases (EB) and bounded rationality (BR) approaches to behavioral economics use different benchmarks for best-practice decision-making tools and related outcomes. For EB, traditional economic (neoclassical) decision-making tools are the benchmark for optimality, where persistent biases and errors in decision making are common and hardwired into human decision makers. For BR, evolved heuristics are best-practice, although errors and suboptimal outcomes occur for informational, computational, and institutional reasons. Conventional neoclassical decision-making tools often result in seriously suboptimal outcomes.

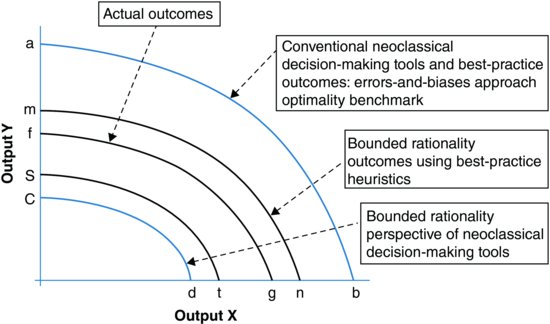

Exhibit 3.2 Asset Prices and the Decision-Making Environment

Note The buying and selling of assets can be modeled as a positive function of the expected net present value of assets. Increases in demand (shifts in the demand curve) can cause manias and bubbles—serious deviations from fundamental values—and, thereafter, severe crashes of asset bubbles. Increases in supply, based on overoptimism and false expectations, can feed back into demand, driving it upward and generating asset bubbles. Internalizing risk, increased moral sentiment, appropriate financial market regulations, improvements to information, and financial education can moderate these movements in demand and supply.

Exhibit 3.2 maps out demand and supply functions for financial or housing assets as these relate to asset prices. A simplifying assumption here is that supply and demand are a positive function of the expected net present value (ENPV) of these assets. Changes in the supply and demand of assets yield changes in price or ENPV of assets. Increases in demand for assets that can cause large manias and bubbles can be moderated by shift factors such as internalizing risk, moral sentiment, improved regulations, improved information sets, and changes to expectations and animal spirits. The same variables affect the supply function. This is an important point because increasing the supply of assets can spark a more than proportionate increase in demand, generating manias and bubbles through feedback loops, illustrated by a shift from S0 to S1 increasing demand from D0 to D2.

SUMMARY

Humans have evolved various decision-making heuristics or fast and frugal shortcuts to cope with a world of bounded rationality. These heuristics might also be optimal given bounded rationality, whereas the neoclassical decision-making alternative might generate suboptimal results. These heuristics can involve both what Kahneman (2011) calls intuitive decision-making processes (fast thinking) or more careful decision-making processes (slow thinking). Sometimes fast thinking processes can generate errors in decision making or decisions that are privately utility maximizing and socially suboptimal, such as the behavior that generated the 2008−2009 stock market and housing market crashes. Much depends on the decision-making environment and the opportunities investors and other decision makers have to learn from their mistakes. Incentives, the quality of information, the ability to understand information, the decision-making process, and moral sentiment all affect the decision-making process, given whatever cognitive shortcomings characterize decision makers.

Behavioral economics recognizes the importance of non-neoclassical decision-making processes as a staple for human decision makers. The errors and biases approach views many of these heuristics as inbred defects in the human decision-making modus operandi, which too often generate errors in decision making and thereby suboptimal outcomes from the perspective of the individual and society at large. Investors are very much party to this defective decision-making apparatus. Moreover, changing error-prone behavior is very difficult. From the perspective of the bounded rationality approach, these heuristics are rational and typically superior in outcomes than what flows from neoclassical decision-making processes. These nonconventional heuristics often make sense given imperfect information, the brain's limited and unique processing capacity, and Knightian uncertainty. From the bounded rationality approach, decision makers can make decision-making errors or make decisions that are suboptimal socially. Changing institutional parameters inclusive of new and improved information sets can seriously and positively affect these decisions.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. Highlight key differences between the two major approaches to behavioral economics for investment behavior.

2. Identify some issues about financial market outcomes that behavioral economics attempts to address and explain.

3. Compare the errors and biases approach to the origins of financial crises with the bounded rationality approach.

4. Identify the critical differences between conventional risk and Knightian uncertainty and the importance of these differences for understanding investor behavior.

5. Discuss the concept of overconfidence and how this relates to investment failure and possible errors in investor decisions.

REFERENCES

Akerlof, George A., and Robert J. Shiller. 2009. Animal Spirits: How Human Psychology Drives the Economy, and Why It Matters for Global Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Altman, Morris. 2004. “The Nobel Prize in Behavioral and Experimental Economics: A Contextual and Critical Appraisal of the Contributions of Daniel Kahneman and Vernon Smith.” Review of Political Economy 16:1, 3−41.

Altman, Morris. 2010b. “Prospect Theory and Behavioral Finance.” In H. Kent Baker and John R. Nofsinger, eds., Behavioral Finance, 191−209. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Altman, Morris. 2012a. “Implications of Behavioral Economics for Financial Literacy and Public Policy.” Journal of Socio-Economics 41:5, 677−690.

Altman, Morris. 2012b. Behavioral Economics for Dummies. Mississauga, Canada: John Wiley & Sons.

Fama, Eugene F. 1965. “Random Walks in Stock Market Prices.” Financial Analysts Journal 21:5, 55–59.

Farmer, Roger E. A. 2010. How the Economy Works: Confidence, Crashes and Self-fulfilling Prophecies. New York: Oxford University Press.

Gigerenzer, Gerd. 2007. Gut Feelings: The Intelligence of the Unconscious. New York: Viking.

Greif, Avner. 1989. “Reputation and Coalitions in Medieval Trade: Evidence on the Maghribi Traders.” Journal of Economic History 49:4, 857–882.

Hayek, Friedrich A. 1945. “The Use of Knowledge in Society.” American Economic Review 35:4, 519−530.

Kagel, John H., and Dan Levin. 2002. Common Value Auctions and the Winner's Curse. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2003. “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics.” American Economic Review 93:5, 1449−1475.

Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 1979. “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decisions under Risk.” Econometrica 47:2, 313−327.

Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky. 2000. Choices, Values and Frames. New York: Cambridge University Press and Russell Sage Foundation.

Keynes, John Maynard. 1936. The General Theory of Employment Interest and Money. London: Macmillan.

Knight, Frank H. 1921. Risk, Uncertainty, and Profit. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Kohn, Marek. 2008. Trust: Self-Interest and the Common Good. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Landa, Janet T. 1994. Trust, Ethnicity, and Identity: The New Institutional Economics of Ethnic Trading Networks, Contract Law, and Gift-Exchange. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

Lewis, Michael. 2010. The Big Short: Inside the Doomsday Machine. New York: Allen Lane.

Malkiel, Burton G. 1973. A Random Walk Down Wall Street, 6th ed. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Malkiel, Burton G. 2003. “Passive Investment Strategies and Efficient Markets.” European Financial Management 9:1, 1–10.

March, James G. 1978. “Bounded Rationality, Ambiguity, and the Engineering of Choice.” Bell Journal of Economics 9:2, 587–608.

Markowitz, Harry. 1952. “Portfolio Selection.” Journal of Finance 7:1, 77–91.

Posner, Richard A. 2009. A Failure of Capitalism: The Crisis of '08 and the Descent into Depression. Cambridge, MA and London: Harvard University Press.

Roubini, Nouriel, and Stephen Mihm. 2010. Crisis Economics: A Crash Course in the Future of Finance. New York: Penguin.

Shefrin, Hersh. 2007. Behavioral Corporate Finance: Decisions That Create Value. New York: McGraw-Hill/Irwin.

Shiller, Robert J. 2000. Irrational Exuberance. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Shiller, Robert J. 2009. “How about a Stimulus for Financial Advice?” New York Times, January 17. Available at www.nytimes.com/2009/01/18/business/economy/18view.html?_r=1.

Shiller, Robert J. 2010. “How Nutritious Are Your Investments?” Project Syndicate. Available at http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/how-nutritious-are-your-investments.

Simon, Herbert A. 1955. “A Behavioral Model of Rational Choice.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 69:1, 99–188.

Simon, Herbert A. 1978. “Rationality as a Process and as a Product of Thought.” American Economic Review 70:2, 1–16.

Simon, Herbert A. 1987. “Behavioral Economics.” In John Eatwell, Murray Millgate, and Peter Newman, eds., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, 266–267. London: Macmillan.

Smith, Vernon L. 2003. “Constructivist and Ecological Rationality in Economics.” American Economic Review 93:3, 465–508.

Taleb, Nassim N. 2010. The Black Swan. New York: Penguin.

Thaler, Richard H. 1988. “Anomalies: The Winner's Curse.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 2:1, 191–202.

Thaler, Richard H. 2009. “Markets Can Be Wrong and the Price Is Not Always Right.” Financial Times. Available at www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/efc0e92e-8121-11de-92e7-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2LsDJHp2e.

Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sustein. 2008. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New Haven, CT and London: Yale University Press.

Todd, Peter M., and Gerd Gigerenzer. 2003. “Bounding Rationality to the World.” Journal of Economic Psychology 24:2, 143–165.

Tversky, Amos, and Daniel Kahneman. 1974. “Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases.” Science 185:4157, 1124–1131.

Wärneryd, Karl-Erik. 2001. Stock-Market Psychology.Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Morris Altman is Head of the School of Economics and Finance at Victoria University of Wellington, where he is also Professor of Behavioral and Institutional Economics. He is also Professor of Economics at the University of Saskatchewan, serving as elected head from 1994 to 2009. Professor Altman was President of the Society for Advancement of Behavioral Economics from 2003 to 2006 and the Association for Social Economics in 2009, and Editor of the Journal of Socio-Economics for nine years until 2012. He was selected for the Marquis Who's Who of the World. Professor Altman has published 90 refereed papers and six books on behavioral economics, economic history, empirical macroeconomics, and public policy. He has made more than 150 international presentations on these subjects and is actively researching behavioral economics involving choice behavior, institutional frames, and ethical considerations.