CHAPTER 12

Financial Counseling and Coaching

INTRODUCTION

We were headed for bankruptcy. We had an immense amount of debt. We were fighting and I felt depressed. I couldn't sleep and it became difficult to make decisions, even if they were minor ones. We didn't know what to do. Then, we learned about financial counseling. . . .

A financial counseling client

The term financial counseling, and by extension, activities performed by financial counselors, has evolved over the past century. In the early- to mid-twentieth century, financial counseling was a phrase most closely associated with investment guidance. Those working as a financial counselor were essentially performing what today might be described as investment advisory functions. Financial counselors were primarily interested in helping clientele increase their wealth through the design and implementation of investment strategies. By the 1960s, the names used by investment professionals to describe their business activities grew to such an extent that few advisors referred to their work as financial counseling. Instead, they adopted titles such as broker, investment representative, investment advisor, financial planner, and money manager to help consumers better understand the services being provided by a firm. Today, financial counseling is generally considered to be descriptive of a reactive, supportive, holistic, and remedial process that focuses on evaluating a client's past and current financial behavior, with an emphasis on current concerns and problems (e.g., overindebtedness, lack of cash flow, and access to public and community support). The ultimate goal associated with both financial counseling and financial coaching involves changing client financial behavior in order to meet financial goals.

The learning outcomes associated with this chapter are threefold. The chapter begins by providing a historical context for financial counseling and coaching. Next, it presents conceptual and theoretical approaches that are commonly used by financial counselors when working with clients. The chapter concludes with a discussion of professional directions in financial counseling in the twenty-first century. Specifically, the chapter describes extensions of financial counseling—coaching, financial therapy, and life planning.

FINANCIAL COUNSELING: A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

Financial counseling has been defined numerous ways. For example, Pulvino and Lee (1979) describe counseling as a process of orderly, systematic steps whereby counselors help clients understand and act on their concerns and of helping others understand who they are and what skills and abilities they have. The authors note that remedial counseling helps clients arrive at some solution and that productive counseling can help clients develop or expand existing resources. Pulvino and Lee comment that preventive counseling can help a client to meet immediate crises that may cause the person undue anxieties through wise money management and planning; preventative counseling can develop the attitude that the client is responsible and capable of controlling the future in a positive, purposeful way.

Williams (1991) views financial counseling as the professional field of assisting clients to obtain economic well-being and security. According to Williams, financial counseling is conceived in a broad sense. It uses skills and information to assist clients in changing behavior in financial management, consumption, lifestyle, and the use of all types of resources in order to obtain and maintain economic security.

By definition, financial counseling shares many of the features associated with psychotherapeutic and family counseling approaches (Williams 1991). For instance, financial counseling is premised on the following notions: (1) Counseling, as a process, is relationship oriented; (2) counseling is cooperative, with both client and counselor contributing to solutions; and (3) counselors ought to be both objective observers and active participants. Pulvino and Lee (1979, p. 5) summarize the client-counselor relationship as follows: “The counselor's responsibility revolves around structure, the client's around content.”

Although similar in many ways to other forms of interpersonal psychotherapy treatment, financial counseling differs from services provided by clinical social workers, psychologists, marriage and family therapists, and others in one significant way; namely, financial counselors do not treat clinical disorders and the focal point of advice and guidance is directed at a client's household or family financial situation. Williams (1991) contends that financial counseling's unique contribution is using economic theory as a guiding principle to improve the well-being of clients by improving standards of living and economic security. This is an important theoretical perspective that helps differentiate financial counseling from other forms of interpersonal therapy.

Often those unfamiliar with the financial services marketplace confuse financial counseling and investment/financial planning. Financial counseling is similar to, but different from, investment advisory work. In the case of investment planning, the goal of the investment management process is to increase wealth in pursuit of long-term financial goals. Financial counseling also differs from financial planning. Financial planners generally review a wide variety of topics related to a client's financial affairs (e.g., insurance, tax, retirement, estate, investments, and special needs). However, few planners get involved with helping clients create a spending plan (i.e., budget), negotiate with creditors, or change spending behaviors. An implicit assumption held by practicing financial planners in the mainstream is that a client's financial situation, as measured by factors such as cash flow and net worth position, should already be healthy enough to implement savings recommendations. That is, the role of a financial planner is to help clients manage their cash flow and net worth position in such a way that wealth is created over the life span as a way to fund tangible financial goals. Financial counselors, on the other hand, tend to provide guidance in ways that will achieve baseline levels of financial health without regard to wealth accumulation.

The market for financial counseling services is potentially quite large. The distressing reality is that few households in the United States can be described as financially healthy enough to value the services of either an investment advisor or financial planner. As of 2012, for example, Americans saved approximately 4 percent of their household income (U.S. Department of Commerce 2012). Financial planners typically recommend a household saving rate closer to 10 percent (Grable, Klock, and Lytton 2012). Based on aggregate figures in the United States, Americans owed over $2.5 trillion in consumer debt (Federal Reserve 2012). Of this amount, consumers held over $800 billion in open-ended revolving debt (i.e., credit card debt). Additionally, the average default rate on home mortgages was close to 10 percent in the period of 2009 to 2012, which represented a 50 percent increase over historical nonpayment rates (U.S. Census Bureau 2010).

These figures alone are not necessarily indicative of financial stress at the household level. If employment rates in a country are high, income is increasing at a rate faster than inflation, and asset values are rising, the ability of households to carry debt is less problematic, making the market demand for financial counseling relatively minor. What makes the statistics just described problematic is that the conditions necessary for aggregate financial health, particularly during the first decades of the twenty-first century, were missing. The situation facing Americans at this writing was not radically different from other distressed periods in American history when Americans faced decreases in wealth and restrictions on credit (e.g., bank run of 1907, deflation and high unemployment of the 1930s, and stagflation and severe household financial stress of the 1970s). In general, describing the average consumer as being in a position of financial health in the twenty-first century or at any sustained period of time during the twentieth century would be difficult.

The preceding discussion highlights the role financial counselors can play in the consumer finance marketplace. Many Americans face financial stress and worry on a daily basis. These consumers are not in a position to save and invest immediately. Rather, they face challenges associated with mismanagement of household financial resources that result in daily financial hardship and hassles. With the lack of assistance and services provided by traditional investment and financial planning professionals, consumers historically could turn to few help providers for expert advice. This has been true for well over a century in the United States (Churaman 1977). Financial counselors have been among the few providers of basic financial education, guidance, and assistance.

Home Economics' Influence on Financial Counseling

Financial counseling has its historical roots in the home economics movement that began in the mid- to late 1800s. The term home economics is a fair description of the early studies conducted to determine how households manage their resources (e.g., time, money, talent, and labor). Although “home economics” has come to be associated with training young women in household tasks such as sewing and cooking, the original basis of this offshoot of economics was to study how consumers and families make decisions when faced with limited resources and nearly unlimited wants. Considering the substantial impact household consumption has on gross domestic product (GDP), determining why the field of home economics failed to gain traction as an academic pursuit is somewhat puzzling.

Today, divisions of home economics in colleges and universities have generally been renamed; departments such as Family and Consumer Sciences, Human Sciences, or Human Ecology Now exist. Traditional economists who study household resource management sometimes refer to their work as “New Home Economics.” These economists apply principles of economics to study consumer and household consumption and decision-making in relation to the allocation of scarce resources, labor, household composition, transportation, fertility, and health (Grossbard-Shechtman 2001).

At nearly the same time, researchers and land-grant university extension specialists were taking steps to organize studies and training dedicated to the establishment of financial counseling as a field of study and practice. Family and consumer economists have traditionally maintained an interest in applying economic principles to develop normative strategies to help people function within the broader economic environment. Yet, the establishment of family resource management, within the context of family economic theory, gave financial counseling a true academic home (Williams 1991). Although some social workers, psychologists, marriage and family therapists, and other help providers (e.g., clergy) were active in providing financial counseling from a non-economic perspective, the financial aspects of literacy and advice was almost always secondary to the help provider's primary calling. Linking family resource management with financial counseling enabled new professionals to describe their primary client interaction activity as financial, rather than relational or psychotherapeutic.

Williams (1991) was among the first researchers to argue for a linkage between family resource management and financial counseling. She maintained that what makes financial counseling unique is the manner in which economic theory is blended with management processes. Specifically, as Williams (p. 7) notes, the basic tasks of financial counseling, as an offshoot of resource management, “are to reconcile expenses with income, provide a balance among needs and wants, maintain a life style in light of hazards against economic security, provide stability while promoting growth, and to distribute resources in a just way (which depends on one's philosophy of justice) equally, efficiently, and effectively.”

Financial Counseling as a Profession

The study of household decision-making is grounded in home, family, and consumer economics. Although financial counseling emerged from these studies in the 1960s (Churaman 1977), people have been providing financial counseling services from a multitude of professional perspectives for well over a century. According to Bagarozzi and Bagarozzi (1980), social workers, the clergy, and other paraprofessionals typically provided financial counseling before the 1960s. Rarely, however, was financial counseling offered as a primary service, but rather as a reaction to a client crisis in conjunction with another presenting issue.

Feldman (1976) categorized financial problems typically encountered by social workers and other help providers into four interrelated domains: (1) learned behavior; (2) behavior brought on through external stimuli, such as economic recession, deflation, and unemployment; (3) family crisis; and (4) financial behavior that is a symptom of emotional and/or personality characteristics. What makes this list unique from behavioral problems studied by family and consumer economists is the inclusion of family dynamic and psychosocial causal factors.

This list also indicates the chasm that existed among help providers who were interested in helping individuals and families deal with financial stress through the 1970s. On one side of the divide were those trained in traditional economics (also known today as standard or traditional finance) who viewed financial behavior from a perspective of normative resource allocation choice, in which decisions were based on quantitative or statistical attributes. On the other side were help providers who viewed financial behavior as a function of other underlying personal and family issues (e.g., overspending as an outcome of child deprivation). Their perspective tended to be more qualitative, with much looser theoretical assumptions related to utility maximization at the household level. The result was a mixed approach to the delivery of financial counseling services. The type of services provided, the materials presented, and the resources gained by a consumer would vary dramatically based on who was providing the counseling service and how the counselor was trained. Bagarozzi and Bagarozzi (1980) reasoned that, in many ways, this haphazard approach to financial counseling process development slowed the training and outcome effectiveness research needed to ground financial counseling as a professional field of endeavor.

Although social workers and the clergy continued to provide financial counseling services throughout the 1970s and still do, the field of financial counseling began to crystallize with the work of family economists and resource management specialists who began to study how traditional economic theory could be blended with organizational behavior, counseling, and household management concepts. Bagarozzi and Bagarozzi (1980) document three ways (i.e., remedial, preventative, and productive) in which financial counseling that originated from a resource management perspective was most often provided during the mid- to late 1970s.

During that time, credit unions were very active in providing financial counseling services to members. Credit unions required their members (i.e., depositors) who applied for a loan typically to receive a form of financial counseling. They provided remedial counseling in cases where a loan was rejected. The purpose of this form of counseling was to help members improve their financial situation so that they could receive loans in the future. Credit unions provided preventative counseling to members who were interested in learning strategies to avoid future financial difficulties. They offered productive counseling to credit union members who needed some form of long-term financial planning—investment, retirement, college savings, and other forms of proactive planning advice.

At the same time, many of the largest U.S. for-profit firms instituted corporate financial counseling programs. According to Bagarozzi and Bagarozzi (1980), some companies required all junior executives to receive financial counseling. This approach to human resource management is almost unheard of today. In general, however, the primary purpose of corporate financial counseling was to provide a competitive working environment by improving the human capital of the workforce by including financial counseling services among other human resource offerings.

The third, and largest, providers of financial counseling services were consumer credit counseling firms of which almost all were operating as 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporations. An active debate still exists as to whether consumer credit counseling firms were truly engaged in a core purpose of financial counseling—behavioral change. Bagarozzi and Bagarozzi (1980, p. 398) contend that many firms, both for profit and nonprofit operations, relegated clients “to the role of passive recipient of a weekly allowance while he/she temporarily surrenders his/her financial responsibilities to the consumer credit counselor.” To understand their concern requires recognizing how these firms typically operated.

Generally, consumer credit counseling companies marketed their expertise (e.g., firms widely advertised these services in radio and television commercials) to the most financially distressed consumers in the marketplace. In almost all cases, these consumers were on the brink of declaring bankruptcy. Knowing that bankruptcy can have a devastating impact on future credit acquisition, these consumers turned to “financial counselors” for immediate help in eliminating their debt while avoiding asset liquidation. On the whole, these firms did as advertised but little more. The financial counselor would meet with the client. During the initial meeting the client would assign responsibility for negotiating with creditors to the financial counseling firm. The financial counselor would work out a debt repayment plan with the client's creditors. Once the plan was established, the client would send a check once a month to the counselor who would distribute payments to each creditor. In most situations, the client and counselor would never meet again. The client's creditors directly paid the counseling firm. Credit card companies, for example, believed that a better approach was to negotiate repayments from a consumer and pay a financial counselor a percent of each payment rather than losing the entire debt through a bankruptcy filing.

This system of financial counseling was the dominant form of help for most resource constrained consumers throughout the century. As a result, financial counseling came to be most associated with debt restructuring and bankruptcy avoidance. In 2005, Congress passed the Uniform Debt Management Services Act. This law effectively altered the functional aspects of the credit counseling industry. For example, the law mandated additional consumer disclosures and prohibited certain practices, such as paying referral fees. Additionally, the act forced the Internal Revenue Service to more heavily scrutinize credit counseling firms. Consumer advocates argued for passage of the act on the basis that few credit counseling firms were truly acting for the public benefit and that nearly all such firms were in-fact for-profit enterprises.

The 2005 act prompted creditors, such as the major credit card companies, to substantially reduce the amount paid to credit counselors. As such, many counseling firms either went out of business or began charging fees for service. The act did promote some positive financial counseling changes, however. Today, for example, anyone who files for bankruptcy is required to receive debt and credit counseling from an approved organization within 180 days of filing for bankruptcy protection. Counseling organizations that want to provide this service must be approved through the U.S. Department of Justice's Trustee Program. Alabama and North Carolina have a separate counselor registration system.

As this discussion highlights, financial counseling has been burdened with two conceptual handicaps. As previously noted, financial counseling has its process roots in the early home economics movement. For whatever reason, many view home economics as a “soft” discipline. Although little evidence supports this perception, many people, both within and outside of the academy, hold a disparaging view of fields associated with the old and new home economics. Second, financial counseling has become most associated with credit counseling. In some respects, this is appropriate. Until the 1990s the majority of firms and organizations providing widespread counseling services were those whose primary role focused on restructuring consumer debt, especially revolving credit (e.g., credit card debt). Although an important and useful outcome associated with financial counseling, debt management is just one of many financial counseling goals, at least when defining financial counseling holistically. Even so, the general assessment of financial counseling in the early twenty-first century does not match well with the aspirations of those who envisioned a professional activity devoted to “assisting clients in the development and creative use of all their resources to achieve economic security or well-being generating alternatives” (Williams 1991, p. 1).

THEORETICAL APPROACHES: A FINANCIAL COUNSELING PERSPECTIVE

Financial counseling might have been founded with the academic study of economics of the home, but it had its coming of age during a time when strategic management was the dominant planning and decision-making framework used in government and corporate organizations (Overton 2008). Strategic management is not, and never was, a theoretical practice model or theoretical approach per se. Rather, strategic management was developed as an applied process approach to thinking focused on documenting how problems should be addressed. This explains how financial counseling practice models—distinct ways in which a practitioner approaches each financial counseling situation, excluding the economic approach—have emerged in an almost atheoretical manner. By contrast, other fields of study have developed practice models only after identifying theoretical perspectives. The pioneers of the modern financial counseling movement were interested in applying concepts from business management, economics, social work, and psychology. They were less interested in explaining behavioral phenomena; this led to the practice of borrowing theoretical concepts and conceptualizing financial counseling as a process akin to widely used strategic management processes being proposed in the 1960s and 1970s.

Consider the financial counseling process model first introduced by Pulvino and Lee (1979). Their model describes the steps involved in the counseling process, beginning with building a counselor-client relationship and ending with recommendation evaluation. The process is not a practice model, but rather a best-practices procedure. When viewed contextually, the process is quite similar to the traditional financial planning method of client engagement advocated by nearly all certification and designation boards (Grable et al. 2012). The process model assumes constant feedback from one element to another. For example, recommendation evaluation involves monitoring each client's progress. As information is obtained, the financial counselor can use new data to help strengthen the client-counselor relationship, diagnose additional needs, generate new counseling alternatives, provide additional core recommendation strategies, and work toward enhanced plan implementation.

One obvious limitation associated with the financial counseling process model is that it is not unique to the financial counseling profession. Financial planners, for instance, use a similar process approach when working with their clientele. Additionally, the process model does not adequately define or explain how financial counselors do or should interact with clients. The process approach only describes the steps that should be taken—in specific order—when working with clients. The exact theoretical approach to be applied (i.e., practice model) is left undefined. For example, a financial counselor whose training is in psychology will approach the process of client interaction differently than someone trained using an economic perspective. Little empirical evidence exists within the literature to suggest that one practice approach is more effective than another. The unfortunate outcome associated with the lack of evidence-based evaluation is that beyond studying the process of counseling, few practitioners have been trained to use clinically adapted practice models.

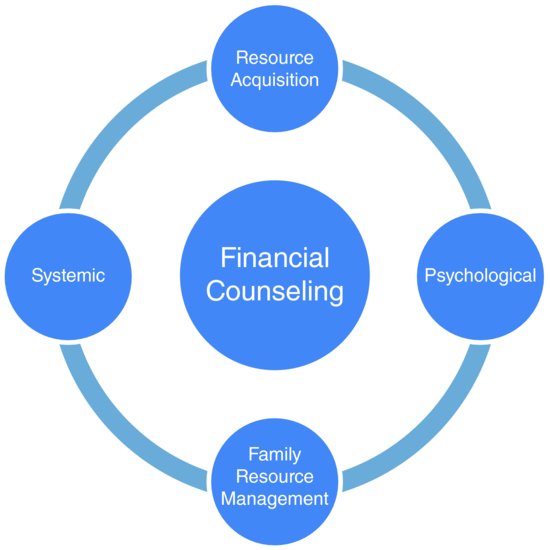

Wall (2002) maintains that the practice of financial counseling can be classified into one of three approaches: (1) psychological, (2) behavioral, and (3) pragmatic. In essence, the categories used in this section incorporate Wall's segmentation more broadly. As Exhibit 12.1 shows, financial counselors tend to use one of four broadly encompassing theoretical perspectives when working with clients. While nearly all counselors may apply a similar client engagement process, each practitioner's preferences, training, and core technical competencies tend to drive the choice of theoretical perspective when working with clients. The remainder of this section describes each theoretical perspective in greater detail.

Exhibit 12.1 Financial Counseling Perspectives

Family Resource Management Perspective

For many decades, Flora Williams, Professor Emeritus at Purdue University, was the leading spokesperson for the development of financial counseling as an academic field of study and practice. One of her foremost contributions to the field was integrating family economic theory with resource management and psychological concepts. She conceptualized her work in the following economic security model (Williams 1991, p. 5), which shows economic security to be a function of a variety of financial, psychosocial, and sociological concepts:

(12.1) ![]()

where E$ = economic security, which is conceptualized to be the result “of income in the total concept through developing, acquiring, and maintaining personal, household, and community resources”

$Mo = money income, transfer payments, and in-kind income

Fa = financial assets

Pa = personal and human assets

Cr = community resources

D = durable goods

At = attitude toward money

Mg = management abilities

Ct = control over financial affairs and resources

VS = value of simplicity

I = insurance; and

A = ability to adjust.

As conceptualized, the resource management approach is premised on several key assumptions. First, household resources are limited. For instance, income, assets, and access to help providers are restricted for most individuals and families. Second, household demands for additional resources are nearly limitless. Third, the inherent conflict between limited resources and unlimited needs results in unmet needs. Fourth, households act in a rational manner by identifying and ranking resources and resource demands when making decisions related to which needs will remain unmet. That is, households make cost-benefit choices in a rational manner by considering financial and opportunity costs, weighing alternatives, and choosing among preferences to reach predetermined financial objectives. Underlying theoretical approaches associated with the resource management approach include the permanent income hypothesis, the relative income hypothesis, and the theory of consumption.

Williams (1991) maintains that those who rely on a resource management perspective as a practice model share a common perspective that includes: (1) helping clients balance income and expenses, (2) developing procedures to help clients balance needs and wants, (3) providing rules to help maintain current living standards while maintaining economic security, (4) promoting financial growth and stability, and (5) teaching clients to distribute resources justly. The way in which these outcomes are accomplished involves combining aspects of economic theory (see key assumptions previously shown) with strategic management processes. Financial counselors who follow a resource management perspective tend to focus efforts on identifying and expanding concepts of income, time usage, social resources, household labor usage, household leadership, and knowledge enhancement related to consumer protection and choice, financial institution information, and public policy. The core underlying purpose driving nearly all financial counselors who employ a resource management perspective involves behavioral change at the individual and household level.

Resource Acquisition Perspective

Financial counselors whose practice model focuses on helping clients acquire resources often work from a social justice theoretical perspective. Broadly defined, social justice combines aspects of progressive economic thinking with social policy activism. Although social justice is a theoretical perspective that is still actively debated, common linkages underlying a social justice perspective include: (1) recognizing the inherent dignity and equality of all individuals, (2) creating opportunities for economic equality, and (3) redistributing income and wealth to produce economic equality.

Garasky, Nielsen, and Fletcher (2008) provide a broad summary of the issues facing low- and moderate-income families in the United States. They show that between 10 and 20 percent of households in the United Stated do not have a bank account. Fewer have adequate savings or asset accumulation strategies to meet an emergency. When viewed holistically, this helps financial acquisition counselors explain why many households engage in credit abuse and borrowing from predatory lenders. In general, financial counselors who use a resource acquisition approach when working with clients focus on helping their clientele increase access to resources, such as income, assets, and insurance. Often, the focus is on helping clients obtain publicly available—either governmental or private donation based—resources. These counselors tend to be less fixated on the behavioral change aspects of financial counseling primarily because they believe the free-market financial marketplace is fundamentally unfair, and this unfairness limits choice and creates uncertainty for vulnerable households. Focusing on behavioral change, at least in relation to resource allocation choices, would be, for a resource acquisition counselor, of modest value compared to improving a client's access to income, asset, and insurance resources.

Psychological Perspectives

Nearly all the discussion up until this point has focused on the economic aspects of financial counseling. In some respects, this is logical. An easy assumption to make is that financial issues should be of primary importance when someone seeks financial counseling services. Consider the resource management and resource acquisition practice models. While these seem at odds with each other, both share a common economic foundation—just different core assumptions. Yet, not all financial counselors view their interactions with clients from a core economic or resource development viewpoint. Some financial counselors incorporate psychologically based approaches in their work with clients. Psychology is the study of normal and abnormal functioning of individuals, in which physiological and psychological aspects are considered and the applied goal is to help individuals with cognitive, behavioral, and emotional problems.

One psychological approach used by financial counselors is the practice of psychoanalysis, which Sigmund Freud developed to help explain how unconscious thought, primarily developed in youth, creates historical precursors of current behavior (Burke 1989; Klontz and Klontz 2009). Multiple philosophical approaches fall under the psychotherapy umbrella. Examples include Gestalt models (i.e., methods that assume self-actualization occurs by focusing on analyzing the present rather than the past), existential frameworks (i.e., approaches that encompass an evaluation of the entire human condition), Adlerian models (i.e., methods that focus on each person's self-centeredness, vulnerability, and powerlessness), and trait-factor counseling (i.e., a general approach designed to help clients value their unique motivations, skills, and abilities) (Williams 1991).

Cognitive/Behavioral Approaches

Cognitive/behavioral counseling is a common psychological approach typically applied to financial counseling. Although conceptualized distinctly when originated in the 1940s and 1950s, many theorists now consider cognitive and behavioral perspectives to be closely linked. As Williams (1991) notes, a practitioner's philosophical approach has a direct influence on the type of recommendations made to help a client deal with financial stress. Cognitive theory suggests that humans make behavioral decisions based on factors such as perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs (Burke 1989; Williams 1991). Those working from a cognitive perspective assert that any behavior can be changed by restructuring how an action or behavioral outcome is contextualized. Behaviorists contend that human activity is a function of stimuli response. That is, some people react to positive stimuli; others respond to negative inducements. Control of stimuli and reinforcement of positive behavior and punishment of negative behavior are characteristics of a behavioral perspective.

During the formative years when the two theoretical perspectives were being intellectualized, a common tendency was to choose one practice approach, rather than both. Today, practitioners more commonly combine elements of the two into a practice framework. Common assumptions held by cognitive/behavioral practitioners include the following: (1) Individuals can control their own environment, (2) human behavior can be changed, (3) people prefer to be in control of their own thoughts and actions, and (4) humans are constantly learning. What differentiates this practice approach from, say, a resource management perspective, is a counseling focus on helping clients gain control over their financial situation rather than a focus on maximizing a client's financial satisfaction, although this can be an outcome associated with the cognitive/behavioral approach.

Techniques that might be used by a cognitive/behavioral counseling practitioner include helping clients redefine what appropriate behavior is and then reinforcing the new definition with rewards and/or punishments. For example, assume a client falls prey to high pressure salespeople when shopping at the mall. The outcome is impulse purchasing, high credit card debt, and financial stress. In contrast, a practitioner employing a psychoanalytic approach might first focus on tracing the client's buying behavior to childhood trauma; a cognitive/behavior practitioner might begin by helping the client redefine what the purpose of shopping means for the client. This might be supplemented with assertiveness training to empower the client to “say no” when feeling pressured to purchase an expensive unneeded item. Depending on the client's preferences, a form of reward or punishment would then be instituted to support behavioral change. For example, each time the client leaves the mall without an impulse purchase, the client may reward his effort by having a milkshake or going to a movie. But when the impulse is too great and the client “fails,” the client might punish his own effort by making a donation to a charitable organization that supports a cause counter to the client's core belief. In this way, the client has cognitively changed his behavioral pattern and reinforced the change through conditioned stimuli.

Systems Perspective

Thus far, financial counseling has been discussed as a personal endeavor, focusing solely on an individual from economic and psychological perspectives. Thinking about finances as an individual concern is easy. However, what happens when more than one person is involved in the financial counseling process? Family systems theory is a perspective that is increasingly being applied when working with individuals and with groups in a financial counseling setting. Family systems theory grew out of psychological processes by addressing similar issues related to cognition, behavior, and emotion. Systems theory also encompasses issues associated with relational aspects of a client's life. Family systems theory has its roots in Bertalanffy's general systems theory and cybernetics, which views an individual as being part of larger family and social systems. Nichols and Schwartz (2001, p. 104) describes a system as “an organic whole whose parts function in a way that transcends their (i.e., individuals) separate characteristics.” In short, this means that individuals are still individuals, but understanding a person's behavior without considering her social or family context is impossible. Like the psychological approaches mentioned, many psychotherapy approaches are rooted in systems theory, including solution-focused grief therapy, Bowen family therapy, and structural therapy, to name a few. Psychological perspectives that primarily address individual needs such as psychoanalysis and cognitive-behavioral approaches can be practiced with a systemic twist. In these cases, the individual's family and social contexts are considered as a way to help understand a client's behavior.

Consider, for example, solution-focused financial counseling. This is a pragmatic, person-centered, and present- and future-oriented counseling approach that helps clients understand their strengths in such a way that client skills are used to meet current and future financial constraints. Sometimes strengths, when defined by solution-focused practitioners, include resources such as income and assets. Often, however, strengths represent forms of human capital (e.g., knowledge and experience) and family and community support systems. Unlike other psychotherapy approaches, a solution-focused financial counselor is not likely to dwell on a client's past actions or mistakes. Instead, the solution-focused counselor will take a stance of curiosity and ask questions to help the client search for exceptions to the disruptive financial behavior, identify what is working well for the client—and encourage the client to do more of it—and help the client take small steps in order to reach established financial goals.

Examples of other systems theory approaches include both Bowen family (intergenerational) systems counseling and structural therapy approaches. These practice models use interventions tailored to change family dynamics. According to Nichols and Schwartz (2001, p. 153), Bowen family systems counseling aims to lower anxiety and increase “the ability to see and regulate one's own role in an interpersonal process” as mechanisms to change behavior. Structural therapy approaches aim to change behavior and the experience of family members to change family functioning patterns by using altering boundaries and realigning subsystems. What separates each of the psychotherapy (i.e., psychological and systemic) practice models mentioned here from more traditional financial counseling approaches is a philosophical perspective that focuses primarily on human attitudes and behavior and less on an assumption of economic rationality or utility maximization.

FINANCIAL COUNSELING IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY

The following discussion highlights three fields of practice that have their roots in traditional financial counseling: (1) financial coaching, (2) financial therapy, and (3) life planning. What makes these three approaches of interest is that each relies on a unique theoretical perspective that helps shape the way in which client issues and concerns are addressed.

Financial Coaching

Wall (2002, p. 17) defines financial counseling in the following way:

Financial counseling is a short-term educative process concerned with helping people to help themselves through the application of financial information, education, and guidance to specific situations. It typically involves helping people clarify issues, explore options, assess alternatives, make decisions, develop strategies, and plan courses of action.

Williams (1991) would argue that what this definition lacks is a focus on behavioral change and would not be alone in offering this critique. Many practitioners and policy makers have expressed concern that financial counseling, as generally practiced, tends to be too short-term oriented. This helps explain the growing interest in exploring new models and approaches that blend the best aspects of financial counseling with other interpersonal behavioral change techniques. One relatively new practice approach is known as financial coaching. Financial coaching is a subset of something known as personal coaching, which has been practiced since the 1970s. Financial coaching combines aspects of financial counseling, financial planning, and personal coaching.

Consider a report funded by the Annie E. Casey Foundation (Collins, Baker, and Gorey 2007). The authors contend that financial coaching is increasingly being applied as an intervention technique that can be used effectively with high-, moderate-, and low-income households. Rather than directing efforts at helping clients solve short-term financial emergencies, financial coaches tend to focus on helping their clientele establish and reach long-term financial goals through directed behavioral change. Financial coaching is premised on five key assumptions: (1) Long-term, rather than short-term goals are of most importance; (2) helping clients achieve long-term financial goals is a collaborative process between client and coach; (3) the coach's primary role is to provide support to clients; (d) each client has unique skills and abilities and the coach's task is to help each client discover and use these resources; and (5) clients have the capacity to change behavior.

According to Collins et al. (2007), those delivering financial coaching are typically volunteer coaches, staff working for a nonprofit organization, and for-profit financial advisors. Yet, financial planners are increasingly incorporating aspects of coaching into their practices (Dubofsky and Sussman 2009). Clients who seek the help of a financial coach often find the term coach to be attractive because the idiom is most often associated with athletic success. Coaches are known to help others set goals, develop strengths to meet and surpass goals, and provide ongoing feedback and guidance. In some ways, financial coaching combines aspects of resource management and cognitive/behavioral frameworks associated with financial counseling. Because of the relative newness of the financial coaching movement, no generally established and monitored ethical guidelines, practice models, or training requirements are available to become a financial coach. However, two organizations provide a professional home for financial coaches: Association for Financial Counseling and Planning (AFPCE) and the International Coach Federation (ICF). Collins et al. conclude that financial coaching may, in fact, provide some individuals and households with meaningful help. Ideal candidates for behavioral coaching are those whose (1) financial situation is relatively simple, (2) financial and personal situation is stable, and (3) ability to engage in behavior change is high. Clientele who need more fundamental resource acquisition help and/or therapy to delve into deep emotional issues typically do not find financial coaching to be quite as valuable.

Financial Therapy

Financial therapy is an emerging area of study and practice that has its roots in the financial counseling, financial planning, and mental health fields. Financial therapy is conceptualized as the integration of cognitive, emotional, behavioral, relational, and economic aspects that promote financial health (Financial Therapy Association 2012). Financial therapy is often practiced when a professional has training in both personal finance and mental health or when a financial professional (e.g., advisor, planner, counselor, or coach) and a mental health clinician (e.g., marriage and family therapist, psychologist, or social worker) collaborate (Archuleta et al. 2011). Financial therapists typically engage in a process to help clients improve their overall quality of life by helping clients improve their financial well-being (Archuleta et al. 2012). The process typically consists of (1) developing a relationship between the client and practitioner, (2) addressing presenting issues and goals, and (3) creating an intervention or introducing tools as a mechanism to meet clients' expected outcomes and goals (e.g., changing one's relationship with money). As financial therapy continues to grow, and as the field transforms into a credible profession, researchers are studying the mechanisms of financial therapy and approaches that are effective in helping clients not only change behavior but also increase overall quality of life, financial well-being, and health. The Journal of Financial Therapy is publishing much of this work.

Life Planning

Life planning, while similar to both financial coaching and financial therapy, has a longer history of development and use. Life planning emerged as an alternative practice approach for financial planners who were less interested in following the systematic financial planning process, which, by definition, tends to be focused heavily on financial problem analyses and solutions. Those advocating the life planning method, such as Carol Anderson, Mitch Anthony, Roy Diliberto, George Kinder, Ross Levin, and Richard Wagner, contend that helping clients achieve financial objectives is essentially ineffectual unless other elements in the client's life are also addressed and improved. This is the core perspective of life planners; namely, the advisor must first help clients establish a general life, rather than financial goals, and objectives. This is the starting point in the client-advisor relationship.

Many definitions of financial life planning are available. For example, Sharpe et al. (2007, p. 2) state that life planning is “a holistic, values-based, client-centered approach to financial planning.” Anthes and Lee (2001, p. 90) define life planning as follows:

A process of helping people focus on the true values and motivations in their lives, determining the goals and objectives they have as they see their lives develop, and using these values, motivations, goals, and objectives to guide the planning process and provide a framework for making choices and decisions in life that have financial and non-financial implications or consequences.

These two definitional frameworks highlight the following core assumptions underlying life planning: (1) Clients are viewed holistically rather than financially; (2) planner advice must be multidimensional, looking at financial and non-financial aspects of each client's situation; (3) financial recommendations and solutions create interactions in other areas of a client's life; and (4) attitudes, feelings, and interactions with others influence a client's behavior. Life planners also describe their work as client-centered planning or counseling, values-based planning or counseling, and as interior-finance (Kinder 2000; Wagner 2000).

The unique contribution of life planning, as it relates to the historical development of financial counseling, is the recurring requirement to continually focus on each client as an individual interacting in a complex world. Rather than separating client goals and objectives into financial and other, life planners attempt to provide counsel that addresses multiple life outcomes simultaneously. To date, however, little empirical evidence suggests that life planning provides better overall outcomes for clients compared to other forms of financial therapy and/or counseling. Sharpe et al. (2007) note that life planners can use effective communication strategies to improve client outcomes by enhancing trust and commitment, but this insight applies to nearly all forms of financial planning, coaching, therapy, and counseling. Whether and how financial life planning will grow in the future is unknown. Given the high financial, emotional, and time commitments necessary to be an effective life planner, the life planning process may become a niche approach used with high net worth clientele who can afford the costs of such specialized care.

SUMMARY

This chapter has highlighted several important factors associated with the manner in which financial counseling and financial coaching is currently practiced. First, nearly all financial counseling practitioners agree that the counseling process as illustrated in Exhibit 12.1 is an appropriate framework to guide client-advisor interactions. Although little empirical evidence supports this assertion, experience among financial counselors suggests the assertion is correct.

Second, no consistent or correct practice model is currently being taught in colleges and universities. As currently practiced, each financial counselor is responsible for selecting a philosophical approach to guide his practice. The approach selected has a direct impact on the type of counseling services provided to clients. Because of this inconsistency, few empirical studies exist to document the effectiveness of financial counseling in general or the usefulness of specific practice management models specifically.

Third, unlike the fields of psychology or marriage and family therapy, those interested in learning the art and craft of financial counseling and financial coaching are forced to choose, sometimes without enough information, a philosophical practice approach before entering school rather than learning multiple approaches and later choosing a framework that matches the student's skills and abilities. This occurs because few academic programs offer more than one philosophical approach when training students. Nearly all students must select between the four philosophical approaches described in the chapter when choosing an academic degree program. This leaves consumers facing a quandary. Few financial counselors and financial coaches advertise their theoretical approach. Some might argue that even fewer counselors and coaches could articulate their practice model approach well enough to create such an advertisement. This means, for better or worse, those seeking financial counseling and financial coaching services receive services that tend to be inconsistent from one counselor/coach to the next with no evidence to support that the approach the counselor/coach is using actually works any better than another approach in any context.

Finally, behavioral change is a common, hoped-for outcome associated with counseling and coaching processes. Yet, the road to change and the empirical evidence to support such change continue to hinder the potential growth and impact of financial counseling and financial coaching as helping professions.

DISCUSSION QUESTIONS

1. When and where did financial counseling develop as a field of study and practice?

2. Identify and briefly explain the four approaches that financial counselors commonly use when engaging with clients.

3. Describe the differences among financial counseling, financial coaching, financial therapy, financial planning, and life planning.

4. Go to www.youtube.com/watch?v=wEfQ4nOz6s8&feature=youtube and watch the video in order answer the following questions:

- What kind of help did this couple receive from Housing and Credit Counseling, Inc. as it relates to this chapter?

- How was the help the couple received from HCCI beneficial?

- If financial counseling services were unavailable for this couple, where could they have sought help?

5. How can the fields of financial counseling and coaching increase their credibility and quality of services?

REFERENCES

Anthes, William, and Shelley A. Lee. 2001. “Experts Examine Emerging Concept of Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 14:6, 90–101. Available at www.fpanet.org/journal/articles/2001_Issues/jfp0601-art11.cfm.

Archuleta, Kristy L., Emily A. Burr, Anita K. Dale, Anthony Canale, Dan Danford, Erika Rasure, Jeff Nelson, Kelley Williams, Kurt Schindler, and Brett Coffman. 2012. “What Is Financial Therapy? Discovering the Mechanisms and Aspects of an Emerging Field.” Journal of Financial Therapy 3:2, 57–78.

Archuleta, Kristy L., Anita K. Dale, Dan Danford, Kelley Williams, Erika Rasure, Emily Burr, Kurt Schindler, and Brett Coffman. 2011. “An Initial Membership Profile of the Financial Therapy Association.” Journal of Financial Therapy 2:2, 1–19.

Bagarozzi, Judith I., and Denis A. Bagarozzi. 1980. “Financial Counseling: A Self Control Model for the Family.” Family Relations 29:3, 396–403.

Burke, Joseph F. 1989. Contemporary Approach to Psychotherapy and Counseling: The Self-Regulation and Maturity Model. Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks-Cole.

Churaman, Charlotte. 1977. “Home Economists at Work: A Roundup of Experiences.” Journal of Home Economics 19:1, 18–21.

Collins, J. Michael, Christi Baker, and Rochelle Gorey. 2007. “Financial Coaching: A New Approach for Asset Building.” A Report for the Annie E. Casey Foundation. Available at http://fyi.uwex.edu/financialcoaching/files/2010/07/Financial_Coaching_Policy_Lab_Paper.pdf.

Dubofsky, David, and Lyle Sussman. 2009. “The Changing Role of the Financial Planner Part 1: From Financial Analytics to Coaching and Life Planning.” Journal of Financial Planning 22:8, 48–57.

Federal Reserve. 2012. “Consumer Credit—G.19.” Available at www.federalreserve.gov/releases/g19/current/default.htm.

Feldman, Frances L. 1976. The Family in Today's Money World. New York: Family Service Association of America.

Financial Therapy Association. 2012. Available at http://financialtherapyassociation.org/About_the_FTA.html.

Garasky, Steven, Robert B. Nielsen, and Cynthia Needles Fletcher. 2008. “Consumer Finances of Low-Income Families.” In Jing Jian Xiao, ed., Handbook of Consumer Finance Research, 223–237. New York: Springer.

Grable, John E., Derek Klock, and Ruth H. Lytton. 2012. A Case Approach to Financial Planning, 2nd ed. Cincinnati, OH: National Underwriter.

Grossbard-Shechtman, Shoshana. 2001. ”The New Home Economics at Colombia and Chicago.” Feminist Economics 7:3, 103–130.

Kinder, George. 2000. The Seven States of Money Maturity. New York: Dell.

Klontz, Brad, and Ted Klontz. 2009. Mind over Money: Overcoming the Money Disorders That Threaten Our Financial Health. New York: Crown Business.

Nichols, Michael P., and Richard C. Schwartz. 2001. Family Therapy: Concepts and Methods, 5th ed. Needham Heights, MA: Pearson.

Overton, Rosalyn. 2008. “Theories of the Financial Planning Profession.” Journal of Personal Finance 7:1, 13–41.

Pulvino Charles J., and James L. Lee. 1979. Financial Counseling: Interviewing Skills. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Sharpe, Deanna L., Carol Anderson, Andrea White, Susan Galvan, and Martin Siesta. 2007. “Specific Elements of Communication that Affect Trust and Commitment in the Financial Planning Process.” Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning 18:1, 2–17.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2010. “Banking, Finance, and Insurance.” Available at www.census.gov/prod/2011pubs/11statab/banking.pdf.

U.S. Department of Commerce. 2012. “Personal Income and Outlays, October 2012.” Available at www.bea.gov/newsreleases/national/pi/pinewsrelease.htm.

Wagner, Richard. 2000. “The Soul of Money.” Journal of Financial Planning 13:8, 50–54.

Wall, Ronald W. 2002. Financial Counseling in Practice: A Practical Guide for Leading Others to Financial Wellness. Honolulu, HI: Financial Wellness Associates.

Williams, Flora L. 1991. Theories and Techniques in Financial Counseling and Planning: A Premier Text and Handbook for Assisting Middle and Low Income Clients. West Lafayette, IN: Purdue Research Foundation.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

John E. Grable is Professor and Athletic Association Endowed Professor of Family Financial Planning at the University of Georgia. He teaches and conducts research in the Certified Financial Planner™ Board of Standards Inc. undergraduate and graduate program at the University of Georgia where he holds an Athletic Association Endowed Professorship. Professor Grable served as the founding editor for the Journal of Personal Finance and coeditor of the Journal of Financial Therapy. His research interests include financial risk tolerance assessment, psycho-physiological economics, and financial planning help-seeking behavior. He has been the recipient of several research and publication awards and grants. Professor Grable is active in promoting the link between research and financial planning practice where he has published numerous refereed papers, coauthored two financial planning textbooks, and coedited a financial planning and counseling book of scales. Professor Grable currently writes a quarterly column for a leading financial services journal. He received his undergraduate degree in business/economics from the University of Nevada, an MBA from Clarkson University, and a PhD in resource management at Virginia Tech.

Kristy L. Archuleta is an Associate Professor in the Personal Financial Planning program in the School of Family Studies and Human Services at Kansas State University and a licensed marriage and family therapist in the state of Kansas. Her research integrates interpersonal and relational factors with financial counseling and planning. She is cofounder and co-director of the Institute of Personal Financial Planning Clinic where she conducts research and practices in the area of financial therapy. Professor Archuleta is a cofounder and currently serves as a board member for the Financial Therapy Association and is coeditor of the Journal of Financial Therapy. She teaches undergraduate and doctoral level financial counseling courses. Professor Archuleta obtained a BS in family relations and child development with a minor in business management from Oklahoma State University, and an MS and PhD in marriage and family therapy with an emphasis in personal financial planning from Kansas State University.