Chapter 40

Income or Loss From Your Business or Profession

As a self-employed person, you report income and expenses from your business or profession separately from your other income, such as income from wages. On Schedule C, you report your business income and itemize your expenses. Any net profit is subject to self-employment tax, as well as regular tax. A net profit can also be the basis of deductible contributions to a SEP or qualified retirement plan, as discussed in Chapter 41.

If you work out of your home, you may deduct home office expenses (40.12).

If you claim a loss on Schedule C, be prepared to show that you regularly and substantially participate in the business. Otherwise, your loss may be considered a passive loss deductible only from passive income, as discussed in Chapter 10.

If you have a business loss that exceeds your other income, you may carry back the loss and claim a refund. For a loss in a tax year ending in 2017, the carryback period is generally two years (40.18).

If you have no employees and business expenses of $5,000 or less, you may be able to file a simplified schedule called Schedule C-EZ (40.6).

40.1 Forms of Doing Business

The legal form of your business determines the way you report business income and loss, the taxes you pay, the ability of the business to accumulate capital, and the extent of your personal liability. It is beyond the scope of this book to discuss the pros and cons of each form. The decision should be made with the services of a professional experienced in both the legal and tax consequences of doing business in a particular form as it applies to your current and future business prospects.

If you are going into business alone, your choices are: operating as a sole proprietor, incorporating, and forming a limited liability company (LLC). If you are going to operate with associates, you may choose to operate as a partnership, a corporation, or an LLC. If you are concerned with limiting your personal liability, your choice is between a corporation or an LLC. An LLC gives you the advantage of limited liability without having to incorporate.

As a sole proprietor, you report business profit or loss on your personal tax return, as explained in this chapter. If you are a partner, you report your share of partnership profit and loss as explained in Chapter 11. If you incorporate, the corporation pays tax on business income. You are taxable on salaries and dividends paid to you by the corporation. You may avoid this double corporate tax by making an S corporation election, which allows you to report corporate income and loss (11.14).

If you operate through an LLC with no co-owners, you report income and loss as a sole proprietor. If you operate an LLC with associates, the LLC reports as a partnership and you report your share of income and loss. However, under check-the-box rules, the LLC may elect on Form 8832 to report as an association taxable as a corporation.

40.2 Reporting Self-Employed Income

You file a Schedule C along with Form 1040 if you are a sole proprietor of a business or a professional in your own practice. If you do freelance work as an independent contractor, you are self-employed and use Schedule C. If you are an employee with a sideline business (e.g., you work for Uber, or TaskRabbit, or Lyft, or Upwork), report the self-employment income and expenses from that business on Schedule C. File a separate Schedule C for each different business you run (e.g., one for being a freelance writer and another for running a boutique). Do not file Schedule C if your business is operated through a partnership or corporation. Seethe guide to Schedule C in 40.6.

On Schedule C, you deduct your allowable business expenses from your business income. Net business profit (or loss) figured on Schedule C is entered on Line 12, Page 1 of Form 1040. Thus, business profit (or loss) is added to (or subtracted from) nonbusiness income on Form 1040 to compute adjusted gross income. This procedure gives you the chance to deduct your business expenses, whether you claim itemized deductions or nonbusiness deductions on Schedule A, such as charitable contributions, taxes, and medical expenses, or you claim the standard deduction where it exceeds your allowable itemized deductions (13.2).

You may be able to file a simplified schedule, Schedule C-EZ, if your income and expenses are below certain limits (40.6).

Passive loss restrictions. Pay special attention to the passive loss restrictions discussed in Chapter 10. Generally, if you do not regularly and substantially participate in your business, losses are considered passive and are deductible only against other passive income.

Recordkeeping. You are required to keep books and records for your business activities, tracking your income and expenses carefully so you can report them accurately on your return. You enter this information according to your method of accounting (40.3).

The tax law does not determine the way in which you must keep these records; today most self-employed taxpayers use computer-based or cloud-based recordkeeping systems.

Tax ID number. As a sole proprietor, you usually do not need a separate tax ID number for Schedule C; you can use your Social Security number as your tax ID number. However, you must obtain an employer identification number if you have any employees and/or maintain a qualified retirement plan (you may also need one to open a business bank account). You can obtain your employer identification number online at www.irs.gov/Businesses/Small-Businesses-&-Self-Employed/Employer-ID-Numbers-EINs.

Table 40-1 Key to Reporting Business and Professional Income and Loss

Item— |

Comments— |

|

Tax return to file |

If you are self-employed, prepare Schedule C to report business or professional income. If your business expenses are $5,000 or less, and you have no employees, you may be able to file a simplified Schedule C-EZ (40.6). If you are a farmer, use Schedule F. You attach Schedule C and/or F to Form 1040. If you operate as a partnership, use Form 1065; if you operate as a corporation, use Form 1120S or Form 1120. If you are a one-member limited liability company that has not elected to be taxed as a corporation, file Schedule C. |

|

Method of reporting income |

The cash or accrual accounting rules determine when you report income and expenses. You must use the accrual basis if you sell a product that must be inventoried unless a safe harbor exception applies. The cash-basis and accrual-basis methods are discussed at 40.3. |

|

Tax reporting year |

There are two general tax reporting years: calendar years that end on December 31 and fiscal years that end on the last day of any month other than December. Your taxable year must be the same for both your business and nonbusiness income. Most business income must be reported on a calendar-year basis. If, as a self-employed person, you report your business income on a fiscal-year basis, you must also report your nonbusiness income on a fiscal-year basis. Use of a fiscal year is restricted for partnerships and S corporations. |

|

Office in home |

To claim home office expenses as a self-employed person, you must use the home area exclusively and on a regular basis either as a place of business to meet or deal with patients, clients, or customers in the normal course of your business or as your principal place of business (40.12). You may claim a standard amount (simplified method) on Schedule C or use Form 8829 to compute the deduction based on actual expenses (40.13). |

|

Social Security coverage |

If you have self-employment income, you may have to pay self-employment tax, which goes to financing Social Security and Medicare benefits; see Chapter 45. |

|

Passive participation in a business |

If you do not regularly, continuously, and substantially participate in the business, your business income or loss is subject to passive activity restrictions. A loss is deductible only against other passive activity income. The passive activity restrictions are discussed in detail in Chapter 10. |

|

Self-employed retirement plan |

You may set up a retirement plan based on business or professional income. Individuals who are self-employed may contribute to a self-employed retirement plan, according to the rules in Chapter 41. |

|

Health insurance |

You may deduct 100% of premiums paid for health insurance coverage for yourself, spouse, and dependents. This deduction is claimed directly from gross income on Line 29 of Form 1040. You may also take advantage of a health savings account plan; see Chapter 41. |

|

Depreciation |

Under the first-year expensing deduction, you generally may deduct up to $510,000 for equipment placed in service in 2017 (42.3). Depreciation rules for assets not deducted under first-year expensing are in Chapter 42. Cars and trucks are subject to special depreciation limits; see Chapter 43. |

|

Net operating losses |

A loss incurred in your profession or business is deducted from other income reported on Form 1040. If the loss (plus any casualty loss) exceeds income, the excess may generally be first carried back two years, and then forward 20 years until it is used up. A loss carried back to a prior year reduces income of that year and entitles you to a refund. A loss applied to a later year reduces income for that year. In some cases a three-year or five-year carryback applies (40.18).You may elect to carry forward your loss for 20 years, foregoing the carryback (40.22). |

|

Sideline business |

You report business income of a sideline business following the rules that apply to full-time business. For example, if you are self-employed, you report business income on Schedule C or C-EZ. You may also have to pay self-employment tax on this income; see Chapter 45. You may also set up a self-employment retirement plan based on such income; see Chapter 41. If you incur losses over several years, the hobby loss rules (40.10) may limit your loss deduction. |

|

Domestic production activities deduction |

If your business produces something in the U.S., you may be eligible for a 9% deduction, which effectively reduces the tax rate you would otherwise pay on this income (40.23). |

40.3 Accounting Methods for Reporting Business Income

Business income is reported on either the accrual or cash basis. If you have more than one business, you may have a different accounting method for each business.

Inventories. Unless a cash method safe harbor (discussed below) applies, the IRS requires inventories at the beginning and end of every taxable year in which the production, purchase, or sale of merchandise is an income-producing factor. If you must keep inventories, you must use the accrual basis.

Cash method. You report income items in the taxable year in which they are received; you deduct all expenses in the taxable year in which they are paid. Under the cash method, income is also reported if it is “constructively” received. You have “constructively” received income when an amount is credited to your account, subject to your control, or set apart for you and may be drawn by you at any time. For example, in 2017 you receive a check in payment of services, but you do not cash it until 2018. You have constructively received the income in 2017, and it is taxable in 2017.

On the cash basis, you deduct expenses in the year of payment. Expenses paid by credit card are deducted in the year they are charged. Expenses paid through a “pay by phone” account with a bank are deducted in the year the bank sends the payment. This date is reported by the bank on your account statements.

Advance payments. Generally, no immediate deduction can be claimed for advance rent or premium covering charges of a later year. However, under a “12-month rule,” you can claim an immediate deduction for prepayments that create rights or benefits that do not extend beyond the earlier of: (1) 12 months after the first date on which the taxpayer realizes rights or benefits attributable to the expenditure, or (2) the end of the taxable year following the taxable year in which the payment is made. However, prepayments of rent remain nondeductible for accrual-method taxpayers under the economic performance rules.

Cash method of accounting limited. The following may not use the cash method: a regular C corporation, a partnership with a C corporation as a partner, a tax shelter, or a tax-exempt trust with unrelated business income. Exceptions: A farming or tree-raising business may use the cash method even if it operates as a C corporation or a partnership with a C corporation as a partner. The cash method may also be used by personal service corporations in the fields of medicine, law, engineering, accounting, architecture, performing arts, actuarial science, or consulting. To qualify, substantially all of the stock must be owned directly or indirectly (through partnerships, S corporations, or personal service corporations) by employees.

If the production, purchase, or sale of merchandise is not an income-producing factor, the cash method may be used by a C corporation or a partnership with a C corporation as a partner if the average annual gross receipts over the prior three-year period were $5 million or less.

Cash method safe harbors. Business owners with average annual gross receipts of $10 million or less may be able to use the cash method if they qualify under the rules of Revenue Procedure 2002-28. For those who do not qualify for the $10 million safe harbor, such as retailers, wholesalers, and manufacturers, a $1 million safe harbor may be available under Revenue Procedure 2001-10. If either safe harbor applies, the cash method can be used even if the business owner would otherwise have to account for inventories under the accrual method. A qualifying taxpayer may not deduct items purchased for resale to customers or used as raw materials for producing finished goods until the year the items are provided to customers if that is later than the year the items were purchased. A qualifying small business that wants to apply the safe harbor guidelines must file for an accounting method change as explained in the instructions to Form 3115.

$10 million safe harbor. The taxpayer’s average annual gross receipts must be $10 million or less for the three taxable years ending with each taxable year ending on or after December 31, 2000. If the test is not met, the cash method cannot be used. If the business has not been in existence for three prior taxable years, including the period of any predecessor, the average is figured for the years it has been in existence.

The cash method safe harbor applies to service businesses, custom manufacturers, and any other taxpayer whose principal activity is not specifically ineligible under Revenue Procedure 2002-28. If a taxpayer’s principal business activity is any of the following, Revenue Procedure 2002-28 bars the cash method safe harbor for that activity: retail or wholesale sales, manufacturing (other than eligible custom manufacturers), publishing, sound recording, or mining. The “principal” activity is the activity that produced the largest percentage of gross receipts in the prior year or the largest average percentage over the three prior years.

Where the taxpayer’s principal activity is not in the prohibited group, the taxpayer may use the cash method for all of its businesses. Where the principal activity is in the prohibited group, the cash method safe harbor may not be used for that activity but it may be used for a separate secondary activity that does not fall within the ineligible group if a complete and separate set of books is maintained for it. For example, a plumbing contractor satisfies the prior-year principal activity test if in the prior year 60% of its gross receipts were from plumbing installations and 40% were from selling plumbing equipment at its retail store. Plumbing installation is a construction activity that is not within the prohibited group. The taxpayer may use the cash method for both the plumbing installation and retail businesses, subject to the timing rule for items purchased for resale and raw materials used to produce finished goods. If the principal activity had been retail sales, the cash method could not be used for that ineligible activity. However, if the taxpayer treats the two activities as separate businesses, each with it own complete set of books, the cash method could be used for the installation business assuming the $10 million gross receipts test is met.

$1 million safe harbor. This safe harbor applies to business owners whose average annual gross receipts are $1 million or less for the three taxable years ending with each taxable year ending on or after December 17, 1998. SeeIRS Publication 538 and Revenue Procedure 2001-10 for details.

Accrual method. On the accrual method, report income that has been earned, whether or not received, unless your right to collect the income is unsure because a substantial contingency may prevent payment; seethe Example below.

Where you are prepaid for services to be performed in a later year, the IRS allows you to defer the prepayment until the next taxable year. Deferral cannot extend beyond the year following the year of payment even if the term of the agreement is for a longer period. Seethe following Examples and Revenue Procedure 2004-34 for further details.

Expenses under the accrual method are deductible in the year your liability for payment is fixed, even though payment is made in a later year. To prevent manipulation of expense deductions, there are tax law tests for fixing the timing of accrual method expense deductions. The tests generally require that economic performance must occur before a deduction may be claimed, but there are exceptions, such as for “recurring expenses.” These rules are discussed in IRS Publication 538.

Expenses owed by an accrual method business owner to a related cash basis taxpayer. A business expense owed to your spouse, brother, sister, parent, child, grandparent, or grandchild who reports on the cash basis may not be deducted by you until you make the payment and the relative includes it as income. The same rule applies to amounts owed to a controlled corporation (more than 50% ownership) and other related entities.

Long-term contracts. Section 460 of the Internal Revenue Code has a special percentage of completion method of accounting for long-term construction contractors.

Capitalize costs of business property you produce or buy for resale. A complicated statute (Code Section 263A) generally requires manufacturers and builders to capitalize certain indirect costs (such as administrative costs, interest expenses, storage fees, and insurance), as well as direct production expenses, by including them in inventory costs; seeIRS Publication 538, Form 3115, and the regulations to Code Section 263A.

Non-accrual experience method (NAE) for deferring service income. Taxpayers using the accrual method who either provide services in the fields of health, law, accounting, actuarial science, engineering, architecture, performing arts, or consulting, or who meet a $5 million annual gross receipts test, can use the non-accrual experience method (NAE). If you qualify, you do not have to accrue amounts that on the basis of your experience will not be collected. However, if interest or a penalty is charged for a failure to make a timely payment for the services, income is reported when the amount is billed. Furthermore, if discounts for early payments are offered, the full amount of the bill must be accrued; the discount for early payment is treated as an adjustment to income in the year payment is made.

Regulation Section 1.448-2T allows four safe harbor NAE methods.

40.4 Tax Reporting Year for Self-Employed

Your taxable year must be the same for both your business and nonbusiness income. If you report your business income on a fiscal year basis, you must also report your nonbusiness income on a fiscal year basis.

Generally, you report the tax consequences of transactions that have occurred during a 12-month period. If the period ends on December 31, it is called a calendar year. If it ends on the last day of any month other than December, it is called a fiscal year. A reporting period, technically called a taxable year, can never be longer than 12 months unless you report on a 52-to-53-week fiscal year basis, details of which can be found in IRS Publication 538. A reporting period may be less than 12 months whenever you start or end your business in the middle of your regular taxable year, or change your taxable year.

To change from a calendar year to fiscal year reporting for self-employment income, you must ask the IRS for permission by filing Form 1128. Support your request with a business reason such as that the use of the fiscal year coincides with your business cycle. To use a fiscal year basis, you must keep your books and records following that fiscal year period.

Fiscal year restrictions. Restrictions on fiscal years for partnerships, personal service corporations, and S corporations are discussed in 11.11 and IRS Publication 538.

40.5 Reporting Certain Payments and Receipts to the IRS

In certain situations, you are required to report payments and receipts to the IRS. If you fail to comply with this reporting, you can be penalized.

Payments to independent contractors. If you pay independent contractors, freelancers or subcontractors a total of $600 or more within the year, you must report all payments to the IRS and the contractors on Form 1099-MISC. For 2017 payments, furnish the contractor with the form and provide a copy to the IRS by January 31, 2018, whether you file by paper or electronically.

The penalty for not filing or filing late depends on the extent of tardiness. For example, the penalty is only $50 per information return if you miss the due date but then file correctly within 30 days. The maximum penalty for 2017 returns filed in 2018 can go as high as $187,500 for a small business, which includes a self-employed individual with average annual gross receipts for three years of $5 million or less.

Receipts of cash payments over $10,000. If you are paid more than $10,000 in cash in one or more related transactions in the course of your business, you must report the transaction to the IRS. “Cash” includes currency, cashier’s checks, money orders, bank drafts, and traveler’s checks having a face amount of $10,000 or less received in a transaction used to avoid this reporting requirement. File Form 8300 with the IRS no later than the 15th day after the date the cash was received. For example, if you receive a $12,000 cash payment on May 1, 2018, you must report it by May 16, 2018.

You have until January 31 of the year following the year of the transaction to give a written statement to the party that paid you. In the example above, this means giving the statement to the party that paid you on May 1, 2018, by January 31, 2019.

There can be civil and even criminal penalties for not filing this return.

Pension distributions to employees. If your business maintains a qualified retirement plan and makes distributions from the plan to you or any employee, you must report the distributions to the IRS on Form 1099-R and furnish a copy to the recipient.

Furnish each contractor and the IRS with a Form 1099-R by January 31, 2018, for 2017 payments.

The penalty is $50, $100, or $260 per return for late filing, depending on the lateness of the return (see the general instructions for Forms 1099).

Retirement plans. If you maintain a qualified retirement plan (other than a SEP or SIMPLE-IRA), you must file an annual information return with the Department of Labor unless your plan is exempt.

No return is required if you (or you and your spouse) are the only participant(s) and plan assets at the end of 2017 do not exceed $250,000. However, regardless of the amount of plan assets, a return is required in the final year of the plan.

File Form 5500-EZ if you (or you and your spouse) are the only participant(s). If your plan covers employees, file Form 5500. The form is an IRS form, but it is filed with the Employee Benefits Security Administration of the U.S. Department of Labor. The due date for the form is the last day of the seventh month after the close of the plan year (e.g., July 31, 2018, for 2017 calendar-year plans).

The late filing penalty is $25 per day (up to $15,000).

Small cash transactions. If you are in a business, such as a convenience store, liquor store, or gas station, that sells or redeems money orders or traveler’s checks in excess of $1,000 per customer per day or issues your own value cards, the government asks that you report any suspicious transactions that exceed $2,000. While this filing isn’t mandatory (there is no penalty for nonfiling), the Treasury Department asks that you report when someone provides false or expired identification, buys multiple money orders in even hundred-dollar denominations or in unusual quantities, attempts to bribe or threaten you or your employee, or does anything else suspicious.

File FinCEN Form 109, “Suspicious Activity Report by Money Services Business,” with the Treasury Department within 30 days of the suspicious activity (it is filed electronically by submitting a “Registration of Money Service Business (RMSB)” form through the BSA e-filing system at http://bsaefiling.fincen.treas.gov/main.html). Under federal law, you are protected from civil liability so the person you report cannot sue for damages.

Wages to employees. If you have any employees, including your spouse or child, you must report wages for the year to the Social Security Administration and the employee. Furnish the employee with Form W-2 and a copy plus a transmittal form with the Social Security Administration by January 31 of the year following the year in which the wages were paid.

40.6 Filing Schedule C

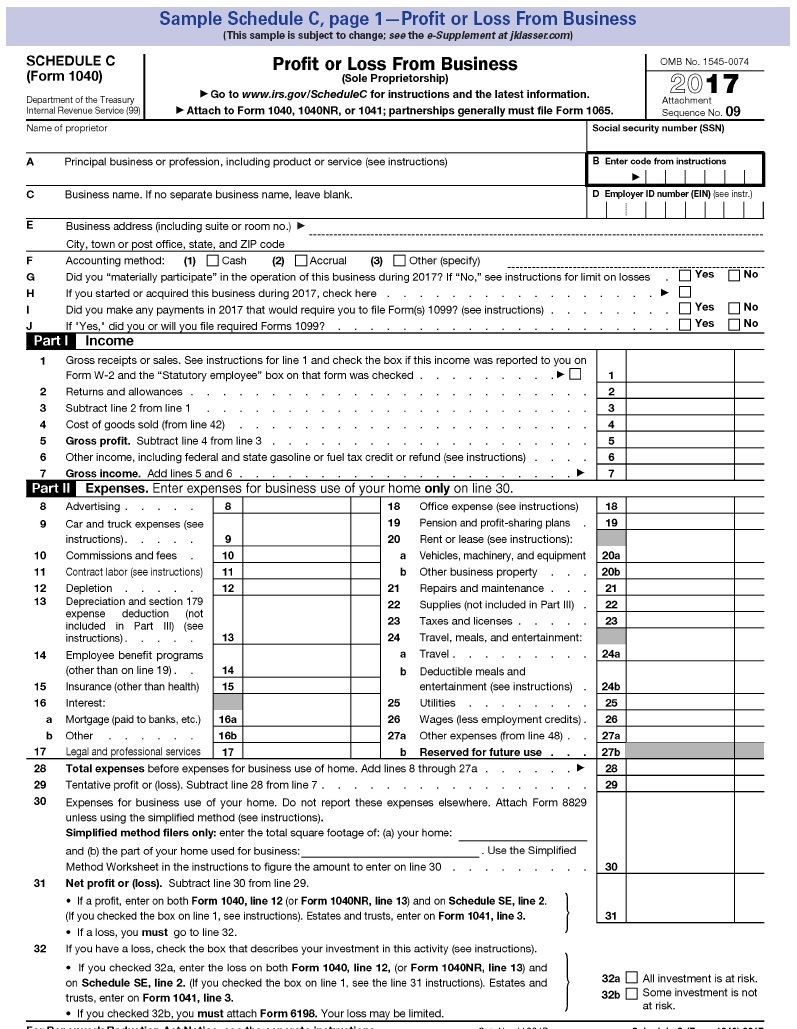

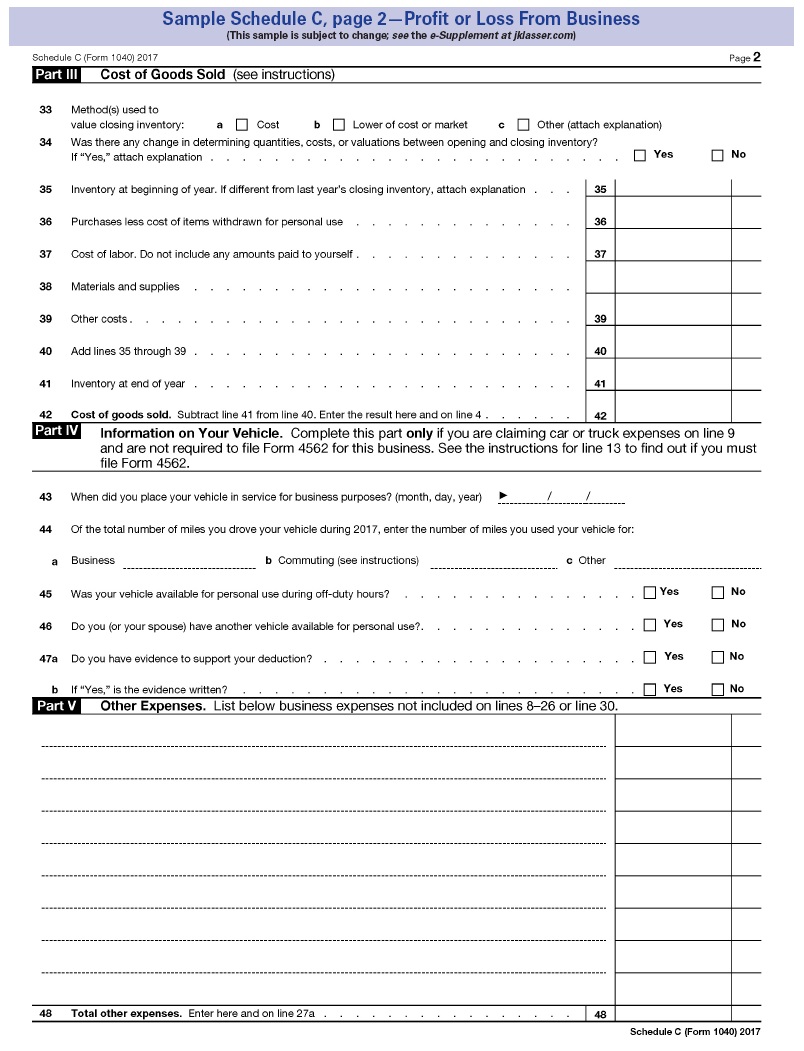

In this section are explanations of how a sole proprietor reports income and expenses on Schedule C, a sample of which is on page 673. If you have more than one sole proprietorship, use a separate Schedule C for each business.

Schedule C-EZ. This simple form is designed for persons on the cash basis who do not have a net business loss and have:

- Business expenses of $5,000 or less;

- No inventory at any time during the year;

- Only one sole proprietorship;

- No employees;

- No home office expense deduction;

- No prior year suspended passive activity losses from this business; and

- No depreciation to be reported on Form 4562.

Statutory employees. Statutory employees report income and expenses on Schedule C. Thus, expenses may be deducted in full on Schedule C rather than as a miscellaneous itemized deduction (19.1), subject to the 2% of adjusted gross income (AGI) floor on Schedule A. Statutory employees are full-time life insurance salespersons, agent or commission drivers distributing certain foods and beverages, pieceworkers, and full-time traveling or city salespersons who solicit on behalf of and transmit to their principals orders from wholesalers and retailers for merchandise for resale or for supplies.

The term full time refers to an exclusive or principal business activity for a single company or person and not to the time spent on the job. If your principal activity is soliciting orders for one company, but you also solicit incidental orders for another company, you are a full-time salesperson for the primary company. Solicitations of orders are considered incidental to a principal business activity if you devote 20% or less of your time to the solicitation activity. A city or traveling salesperson is presumed to meet the principal business activity test in a calendar year in which he or she devotes 80% or more of working time to soliciting orders for one principal.

IRS regulations give this example: A salesperson’s principal activity is getting orders from retail pharmacies for a wholesale drug company called Que Company. He occasionally takes orders for two other companies. He is a statutory employee only for Que Company.

If you are a statutory employee, your company checks Box 13 on Form W-2, identifying you as a statutory employee. Although a statutory employee may treat job expenses as business expenses, the employer withholds FICA (Social Security and Medicare) taxes on wages and commissions.

If you received a Form W-2 with “Statutory employee” checked in Box 13, include the income from Box 1 of the W-2 on Line 1 of Schedule C (or C-EZ) and check the box on that line. If you also have self-employment earnings from another business, you must report the self-employment earnings and statutory employee income on separate Schedules C. If both types of income are earned in the same business, allocate the expenses between the two activities on the separate schedules.

Gross receipts or sales on Schedule C. Your gross receipts are reported on Line 1 of Schedule C.

If you received business payments through merchant credit cards and third party networks such as PayPal and Google Checkout, such payments should have been reported to you by banks and third party network payers in Box 1 of Form 1099-K if your total transactions exceeded $20,000 and the number of transactions exceeded 200 for the year. No special reporting on Schedule C is required; report gross receipts as you would whether or not you receive Form 1099-K. As discussed above, “statutory employee” income from Form W-2 is entered on Line 1.

Do not report as receipts on Schedule C the following items:

- Gains or losses on the sale of property used in your business or profession. These transactions are reported on Schedule D and Form 4797.

- Dividends from stock held in the ordinary course of your business. These are reported as dividends from stocks that are held for investment.

Deductions on Schedule C. You can usually deduct most expenses incurred in your business, although there may be limits on the amount or timing of deductions. The basic requirement for deductibility is that expenses must be ordinary and necessary to your business. An ordinary expense is one that is common and accepted in your business; a necessary expense is one that is helpful and appropriate to your business.

Deductible business expenses are claimed in Part II; the descriptive breakdown of items is generally self-explanatory. However, note these points:

Car and truck expenses (Line 9): In the year you place a car in service, you may choose between the IRS mileage allowance and deducting actual expenses, plus depreciation. You must also attach Form 4562 to support a depreciation deduction; see Chapter 43.

Depreciation (Line 13): Enter here the amount of your annual depreciation deduction or Section 179 expensing. A complete discussion of depreciation may be found in Chapter 42. You must figure your deduction on Form 4562 for assets placed in service in 2017, or for cars, computers, or other “listed property,” regardless of when the assets were placed in service.

Employee benefit programs including health insurance (Line 14):Enter your cost for the following programs you provide for your employees: accident or health plans; group-term life insurance; long-term care insurance coverage; wage continuation; self-insured medical reimbursement plans; dependent care assistance; educational assistance programs; supplemental unemployment benefits; and prepaid legal expenses. Retirement plan contributions for employees, such as to pension and profit-sharing plans, are reported separately on Line 19.

Insurance other than health insurance (Line 15): Insurance policy premiums for the protection of your business, such as accident, burglary, embezzlement, marine risks, plate glass, public liability, workers’ compensation, fire, storm, or theft, and indemnity bonds upon employees, are deductible. State unemployment insurance payments are deducted here or as taxes if they are considered taxes under state law.

Premiums paid on an insurance policy on the life of an employee or one financially interested in a business, for the purpose of protecting you from loss in the event of the death of the insured, are not deductible.

Under a “12-month” rule, prepaid premiums can be deducted in the year paid if the coverage term does not extend more than 12 months beyond the first date coverage is received, and also does not extend beyond the taxable year following the year in which the premium is paid.

Premiums for disability insurance to cover loss of earnings when out ill or injured are nondeductible personal expenses. But you may deduct premiums covering business overhead expenses.

Interest (Line 16): Include interest on business debts, but prepaid interest that applies to future years is not deductible.

Deductible interest on an insurance loan is limited if you borrow against a life insurance policy covering yourself as an employee or the life of any other employee, officer, or other person financially interested in your business. Interest on such a loan is deductible only if the policy covers an officer or 20% owner (no more than five such “key persons” can be counted) and the loan is no more than $50,000 per person. If you own policies covering the same employees (or other persons) in more than one business, the $50,000 limit applies on an aggregate basis to all the policies. The interest deduction limit applies even if a sole proprietor borrows against a policy on his or her own life and uses the proceeds in a business; interest is not deductible to the extent the loan exceeds $50,000.

Pension and profit-sharing plans (Line 19): SEP, SIMPLE, or qualified retirement plan contributions made for your employees are entered here; contributions made for your account are entered directly on Form 1040 (Line 28) as an adjustment to income. In addition, you may have to file an information return by the last day of the seventh month following the end of the plan year (41.8).

Rent on business property (Line 20): Rent paid for the use of lofts, buildings, trucks, and other equipment is deductible. Prepaid rents can be deducted by cash-method taxpayers in the year of payment if the rent term does not extend more than 12 months beyond the first day of the lease and also not beyond the end of the taxable year following the taxable year in which the prepayment is made. However, the economic performance rules prevent accrual-method taxpayers from deducting prepaid rent; economic performance occurs only ratably over the lease term.

Taxes on leased property that you pay to the lessor are deductible as additional rent.

Repairs (Line 21): The cost of repairs and maintenance generally is deductible. Expenses of repairs or replacements that increase the value of property, make it more useful, or lengthen its life are capitalized and their cost recovered through depreciation unless safe harbors or de minimis rules under final repair regulations are used.

Taxes (Line 23):

Deduct real estate and personal property taxes on business assets here. Also deduct your share of Social Security and Medicare taxes paid on behalf of employees and payments of federal unemployment tax. Federal highway use tax is deductible. Federal import duties and excise and stamp taxes normally not deductible as itemized deductions are deductible as business taxes if incurred by the business. Taxes on business property, such as an ad valorem tax, must be deducted here; they are not to be treated as itemized deductions. However, the IRS holds that you may not deduct state income taxes on business income as a business expense. Its reasoning: Income taxes are personal taxes even when paid on business income. As such, you may deduct state income tax only as an itemized deduction on Schedule A. The Tax Court supports the IRS rule on the grounds that it reflects Congressional intent toward the treatment of state income taxes in figuring taxable income.

For purposes of computing a net operating loss, state income tax on business income is treated as a business deduction.

If you pay or accrue sales tax on the purchase of nondepreciable business property, the sales tax is a deductible business expense. If the property is depreciable, add the sales tax to the cost basis for purposes of computing depreciation deductions.

Travel, meals, and entertainment (Line 24): Travel expenses on overnight business trips while “away from home” (20.5) are claimed on Line 24a. Total meals and entertainment expenses, reduced by 50%, are claimed on Line 24b. The 50% limit for meals and entertainment is increased to 80% for transportation industry workers subject to the Department of Transportation hours of service limits.

Self-employed persons may use the IRS meal allowance rates (20.4), instead of claiming actual expenses. Recordkeeping requirements for travel and entertainment expenses are discussed in Chapter 20 (20.26–20.28).

Utilities (Line 25): Deduct utilities such as gas, electric, and telephone expenses incurred in your business. However, if you have a home office (40.12), you may not deduct the base rate (including taxes) of the first phone line into your home (19.15).

Wages (Line 26): You do not deduct wages paid to yourself. You may deduct reasonable wages paid to family members who work for you. If you have an employee who works in your office and also in your home, such as a domestic worker, you deduct that part of the salary allocated to the work in your office. If you claim any employment-related tax credit (40.26), the wage deduction is reduced by the credit.

Other expenses (Line 27): In Part V of Schedule C, you list deductible expenses not reported in Part II, such as amortizable business start-up costs (40.11), business-related education (33.15), subscriptions, and professional dues, and enter the total on Line 27.

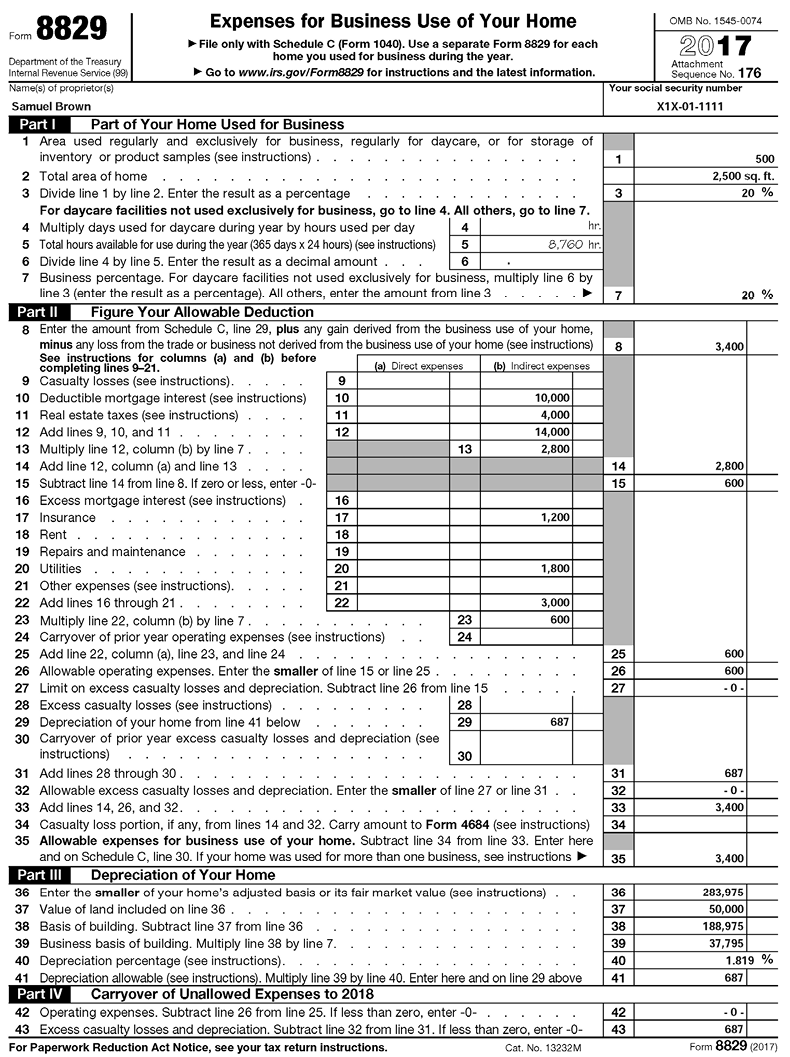

Home office deduction (Line 30): If you qualify for this deduction, it is first figured separately on Form 8829 if you use the actual expense method, or multiply your square footage (up to 300 square feet) by $5; the deductible amount is then entered here (40.12).

Net profit (or loss) (Line 31): The net results of your entries on lines 1 through 30 will produce a profit (or loss). A profit, called net earnings from self-employment, is subject to self-employment tax (45.1-45.6). It may also be subject to a 0.9% additional Medicare tax (28.2).

40.7 Deductions for Professionals

The following expenses incurred by self-employed professionals in the course of their work are generally allowed as deductions from income when figuring profit (or loss) from their professional practices on Schedule C:

- Dues to professional societies.

- Operating expenses and repairs of car used on professional calls.

- Supplies.

- Subscriptions to professional journals.

- Rent for office space.

- Cost of fuel, light, water, and telephone used in the office.

- Salaries of assistants.

- Malpractice insurance (40.6).

- Cost of books, information services, professional instruments, and equipment with a useful life of one year or less. Professional libraries are depreciable if their value decreases with time. Depreciation rules are discussed in 42.1.

- Fees paid to a tax preparer for preparing Schedule C and related business forms.

Professionals as employees. Professionals who are not in their own practice may not deduct professional expenses on Schedule C. Salaried professionals may deduct professional expenses only as miscellaneous itemized deductions on Schedule A, subject to the 2% of adjusted gross income (AGI) floor (19.1). However, “statutory” employees may use Schedule C (40.6).

The cost of preparing for a profession. You may not deduct the cost of a professional education (33.16).

The IRS does not allow a deduction for the cost of a license to practice. However, the Tax Court has allowed attorneys to amortize over their life expectancy bar admission fees paid to state authorities.

Payment of clients’ expenses. An attorney may follow a practice of paying his or her clients’ expenses in pending cases. The IRS will disallow a deduction claimed for these payments on the grounds that the expenses are those of the client, not the attorney. The courts agree with the IRS position where there is a net fee agreement. In a net fee agreement, expenses first reduce the recovery before the attorney takes a fee. However, where the attorney is paid under a gross fee agreement, an appeals court has reversed a Tax Court decision that disallowed the deduction of the attorney’s payment of client expenses. Under a gross fee agreement, the attorney’s fee is based on the gross award; the prior payment of expenses does not enter into the fee agreement and so is not reimbursed. Because he would not be reimbursed, an attorney claimed his payment of client expenses was deductible. An appeals court accepted this argument and allowed the deduction. The court allowed the deduction although California law disapproved of the practice of paying client expenses without a right of reimbursement. The court believed that there is no ethical difficulty with the practice and other jurisdictions approve of it. It is necessary for and it is the practice of personal injury firms to pay the costs of many of their clients.

If you are not allowed a current deduction for payment of clients’ expenses, you may deduct your advance as a bad debt if the claim is worthless in another year (40.6).

An attorney might deduct a payment to a client reimbursing the client for a bad investment recommended by the attorney. A court upheld the deduction on the grounds that the reimbursement was required to protect the reputation of an established law practice. However, no deduction is allowed when malpractice insurance reimbursement is available but the attorney fails to make a claim.

Daily business lunches with associates have been held to lack business purpose. Courts agree with the IRS that professionals do not need to have lunch together every day to talk shop. The cost of the meals is therefore not deductible.

40.8 Nondeductible Expense Items

Capital expenditures may not be deducted. Generally, the cost of acquiring an asset or of prolonging its life is a capital expenditure that must be amortized over its expected life. If the useful life of an item is less than a year, its cost, including sales tax on the purchase, is deductible. Otherwise, you generally may recover your cost only through depreciation except to the extent first-year expensing applies (42.3). IRS regulations provide safe harbors, including a “12-month” rule, for expenditures relating to intangible assets or benefits (40.3).

Expenses while you are not in business. You are not allowed to deduct business expenses incurred during the time you are not engaged in your business or profession.

Bribes and kickbacks. Bribes and kickbacks are not deductible if they are illegal under a federal or a generally enforced state law that subjects the payer to a criminal penalty or provides for the loss of license or privilege to engage in business. A kickback, even if not illegal, is not deductible by a physician or other person who has furnished items or services that are payable under the Medicare or Medicaid programs. A kickback includes payments for referral of a client, patient, or customer.

In one case, the IRS, with support from the Tax Court and a federal appeals court, disallowed a deduction for legal kickbacks paid by a subcontractor. The courts held that the kickbacks were not a “necessary” business expense because the contractor had obtained nearly all of its other contracts without paying kickbacks, including contracts from the same general contractor bribed here.

40.9 How Authors and Artists May Write Off Expenses

Self-employed authors, artists, photographers, and other qualifying creative professionals may write off business expenses as they are paid. The law (Code Section 263A) that requires expenses to be amortized over the period income is received does not apply to freelancers who personally create literary manuscripts, musical or dance scores, paintings, pictures, sculptures, drawings, cartoons, graphic designs, original print editions, photographs, or photographic negatives or transparencies. Furthermore, expenses of a personal service corporation do not have to be amortized if they directly relate to expenses of a qualifying author, artist, or photographer who owns (or whose relatives own) substantially all of the corporation’s stock.

Current deductions are notallowed for expenses relating to motion picture films, videotapes, printing, photographic plates, or similar items.

An author or artist with expenses exceeding income may be barred by the IRS from claiming a loss under a profit motive test; in that case, the profit-presumption rule (40.10) may allow a deduction of the loss.

40.10 Deducting Expenses of a Sideline Business or Hobby

There is a one-way tax rule for hobbies: Income from a hobby is taxable as “other income” on Form 1040; expenses are deductible only to the extent you report hobby income, and the deduction is limited on Schedule A by the 2% of adjusted gross income (AGI) floor for miscellaneous itemized deductions (19.1) and subject to the reduction in itemized deductions for high-income taxpayers (13.7). Hobby losses are considered nondeductible personal losses; these losses in excess of income from a hobby activity do not carry over and are lost forever. A profitable sale of a hobby collection or activity held long term is taxable as capital gain; losses are not deductible.

How to deduct hobby expenses. If the profit presumption discussed later does not apply and the activity is held not to be engaged in for profit, business operating expenses and depreciation are deductible only as miscellaneous itemized deductions and only up to the extent of income from the activity; a deduction for expenses exceeding the income is disallowed.

A special sequence is followed in determining which expenses are deductible from income. Deducted first on Schedule A are amounts allowable without regard to whether the activity is a business engaged in for profit, such as mortgage interest and state and local taxes, as well as casualty losses (after applying the dollar and percentage casualty floors (18.12)). These amounts are deductible in full on the appropriate lines of Schedule A without regard to income from the activity. However, they reduce gross income from the activity for purposes of figuring whether other deductions may be claimed. If after deducting these amounts from gross income there is any income remaining, “business” operating expenses such as wages, utilities, insurance premiums, interest, advertising, repairs, and maintenance may be claimed. Then deduct depreciation and excess casualty losses not allowed in the first step to the extent of remaining income. The “business” expenses, depreciation, and excess casualty losses are allowed only as miscellaneous itemized deductions subject to the 2% of AGI floor (19.1). Thus, even if the expenses offset income from the activity, none of the expenses will be deductible unless your total miscellaneous expenses (including those from the activity) exceed 2% of your adjusted gross income.

Presumption of profit-seeking motive. You are presumed to be engaged in an activity for profit if you can show a profit in at least three of the last five years, including the current year. If the activity is horse breeding, training, racing, or showing, the profit presumption applies if you show profits in two of the last seven (including current) years. The presumption does not necessarily mean that losses will automatically be allowed; the IRS may try to rebut the presumption. You would then have to prove a profit motive by showing these types of facts: You spend considerable time in the activity; you keep businesslike records; you have a written business plan showing how you plan to make a profit; you relied on expert advice; you expect the assets to appreciate in value; and losses are common in the start-up phase of your type of business.

Election postpones determination of profit presumption. If you have losses in the first few years of an activity and the IRS tries to disallow them as hobby losses, you have this option: You may make an election on Form 5213 to postpone the determination of whether the above profit presumption applies. The postponement is until after the end of the fourth taxable year (sixth year for a horse breeding, training, showing, or racing activity) following the first year of the activity. For example, if you enter a farming activity in 2017, you can elect to postpone the profit motive determination until after the end of 2021. Then, if you have realized profits in at least three of the five years (2017–2021), the profit presumption applies. When you make the election on Form 5213, you agree to waive the statute of limitations for all activity-related items in the taxable years involved. The waiver generally gives the IRS an additional two years after the filing due date for the last year in the presumption period to issue deficiencies related to the activity.

To make the election, you must file Form 5213 within three years of the due date of the return for the year you started the activity. If before the end of this three-year period you receive a deficiency notice from the IRS disallowing a loss from the activity and you have not yet made the election, you can still do so within 60 days of receiving the notice. These election rules apply to individuals, partnerships, and S corporations. An election by a partnership or S corporation is binding on all partners or S corporation shareholders holding interests during the presumption period.

40.11 Deducting Expenses of Looking for a New Business

When you are planning to invest in a business, you may incur preliminary expenses for traveling to look at the property and for legal or accounting advice. Expenses incurred during a general search or preliminary investigation of a business are not deductible, including expenses related to the decision whether or not to enter a transaction. However, when you go beyond a general search and actually go into business, you may elect to deduct or amortize your start-up costs.

Deductible or amortizable start-up costs. If you began your business in 2017, up to $5,000 of eligible start-up expenses is allowed. The limit is reduced by the amount of start-up costs exceeding $50,000. Start-up costs over the first-year deduction limit may be amortized over 15 years. An election to amortize is made by claiming the deduction on Form 4562, and it is then entered in Part V (“Other Expenses”) of Schedule C.

Eligible costs include investigating and setting up the business, such as expenses of surveying potential markets, products, labor supply, and transportation facilities; travel and other expenses incurred in lining up prospective distributors, suppliers, or customers; salaries or fees paid to consultants or attorneys, and fees for similar professional services. The business may be one you acquire from someone else or a new business you create.

Organizational costs for a partnership or corporation. Costs incident to the creation of a partnership or corporation are also deductible or amortizable under the rules for start-up costs discussed above. For a partnership, qualifying expenses include legal fees for negotiating and preparing a partnership agreement, and management, consulting, or accounting fees in setting up the partnership. No deduction or amortization is allowed for syndication costs of issuing and marketing partnership interests such as brokerage and registration fees, fees of an underwriter, and costs of preparing a prospectus.

For a corporation, qualifying expenses include the cost of organizational meetings, incorporation fees, and accounting and legal fees for drafting corporate documents. Costs of selling stock or securities, such as commissions, do not qualify.

An election to amortize is made on Part VI of Form 4562 for the first year the partnership or corporation is in business. The election on Form 4562 and the required statement must be filed no later than the return due date, including extensions, for the year in which the business begins.

Nonqualifying expenses. Deductible and amortizable expenses are restricted to expenses incurred in investigating the acquisition or creation of an active business, and setting up such an active business. They do not include taxes or interest. Research and experimental costs are not start-up costs, but are separately deductible or amortizable; seeIRS Publication 535 and Code Section 174. For rental activities to qualify as an active business, there must be significant furnishing of services incident to the rentals. For example, the operation of an apartment complex, an office building, or a shopping center would generally be considered an active business.

If you do not elect to deduct or amortize qualifying start-up costs, you treat the expenses as follows:

- Costs connected with the acquisition of capital assets are capitalized and depreciated; and

- Costs related to assets with unlimited or indeterminable useful lives are recovered only on the future sale or liquidation of the business.

If the acquisition fails. Where you have gone beyond a general search and have focused on the acquisition of a particular business, but the acquisition falls through, you may deduct the expenses as a capital loss.

Job-hunting costs. You may deduct the expenses of looking for a new job under certain circumstances (19.8).

40.12 Home Office Deduction

If you operate your business from your home, using a room or other space as an office or area to assemble or prepare items for sale, you may be able to deduct expenses such as utilities, insurance, repairs, and depreciation allocated to your business use of the area. Collectively, these expenses are deducted as a single write-off, called the home office deduction. There are now two ways to figure the deduction: using your actual expenses or relying on an IRS-set standard amount (40.13).

Exclusive and regular use. To deduct home office expenses, you must prove that you use the home area exclusively and on a regular basis either as:

- A place of business to meet or deal with patients, clients, or customers in the normal course of your business (incidental or occasional meetings do not meet this test), or

- Your principal place of business.Your home office will qualify as your principal place of business if you spend most of your working time there and most of your business income is attributable to your activities there.

Administrative (recordkeeping) activity. A home office meets the principal place of business test (Test 2), even if you spend most of your working time providing services at outside locations, if: (1) you use it regularly and exclusively for administrative or management activities of your business and (2) you have no other fixed location where you do a substantial amount of such administrative work. Self-employed persons are the beneficiaries of this administrative/management rule. Employees usually may not take advantage of the rule because of the application of the convenience-of-the-employer test to an employee’s use of a home office; seethe Example at 19.14. Examples of administrative and management activities include billing customers, clients, or patients; keeping books and records; ordering supplies; setting up appointments; forwarding orders; and writing reports.

According to the IRS, performance of management or administrative activities under the following conditions do not disqualify a home office as a principal place of business:

- You have a company send out your bills from its place of business (see Example 1 below).

- You do administrative or management activities at times from a hotel or automobile (seeExample 2 below).

- You occasionally conduct minimal administrative or management activities at a fixed location outside your home.

- You have suitable space to do administrative or management work outside your home but choose to use your home office for such activities (seeExample 3 below).

If you work at home and also outside of your home at other locations and you do not meet the administrative/management rule, deductions of home office expenses should be supported by evidence that your activities at home are relatively more important or time consuming than those outside your home.

Exclusive and regular business use of home area required. If you use a room, such as a den, both for business and family purposes, be prepared to show that a specific section of the den is used exclusively as office space. For example, a real estate operator was not allowed to deduct the cost of a home office, on evidence that he also used the office area for nonbusiness purposes. A partition or other physical separation of the office area is helpful but not required.

Under the regular basis test, expenses attributable to incidental or occasional trade or business use are not deductible, even if the room is used for no other purpose but business.

Even if you meet these tests, your deduction for allocable office expenses may be substantially limited or barred by a restrictive rule that limits deductions to the income from the office activity. This computation is made on Form 8829 (40.15).

Multiple business use of home office. If you use a home office for more than one business, make sure that the home office tests are met for all businesses before you claim deductions. If one business use qualifies and another use does not, the IRS will disallow deductions even for the qualifying use, seethe following paragraph.

Employee with sideline business. Employees who use a home office for their job and for a sideline business also should be aware of this problem. Most employees are unable to show that their home office is the principal place of their work (19.14). Claiming an unallowable deduction for employee home office use will jeopardize the deduction for sideline business use. This happened to Hamacher, who as a self-employed actor earned $24,600 over a two-year period from an Atlanta theater and a few radio and television commercials. He also earned $18,000 each year as the administrator of an acting school at the theater. For his job as administrator, Hamacher shared an office at the theater with other employees. He had access to this office during nonbusiness hours. He also used one of the six rooms in his apartment for an office. Because of interruptions at the theater, he used the home office to work on the school curriculum and select plays for the theater. In connection with his acting business, he used the home office to receive phone calls, to prepare for auditions, and rehearse for acting roles.

The IRS disallowed his deduction for both self-employment and employee purposes because Hamacher’s office use as an employee did not qualify. The Tax Court agreed. A single-office space may be used for different business activities, but all of the uses must qualify for a deduction. Here, Hamacher’s use of the home office as an employee did not qualify. He had suitable office space at the theater. He was not expected or required to do work at home. As the employee use of the home office did not qualify, the Tax Court did not have to determine if the sideline business use qualified. Even if it had qualified, no allocation of expenses between the two uses would have been made. By requiring that a home office be used “exclusively” as a principal place of business or place for seeing clients, patients, or customers, the law imposes an all-or-nothing test.

Separate structure. If in your business you use a separate structure not attached to your home, such as a studio adjacent but unattached to your home, the expenses are generally deductible if you satisfy the exclusive use and regular basis tests discussed earlier. A separate structure does not have to qualify as your principal place of business or a place for meeting patients, clients, or customers. However, an income limitation (40.15) applies. In one case, a taxpayer argued that an office located in a separate building in his backyard was not subject to the exclusive and regular business use tests and the gross income limitation. However, the IRS and Tax Court held that it was. The office building was “appurtenant” to the home and thus part of it, based on these facts: The office building was 12 feet away from the house and within the same fenced-in residential area; it did not have a separate address; it was included in the same title and subject to the same mortgage as the house; and all taxes, utilities, and insurance were paid as a unit for both buildings.

Day-care services. The exclusive-use test does not have to be met for business use of a home to provide day-care services for children and handicapped persons, or persons age 65 or older, provided certain state licensing requirements are met. If part of your home is regularly but not exclusively used to provide day-care services, you may deduct an allocable part of your home expenses. You allocate expenses by multiplying the total costs by two fractions: (1) The total square footage in the home that is available for day-care use throughout each business day and regularly so used, divided by the total square footage for the home. (2) The total hours of business operation divided by the total number of hours in the year (8,760 in 2017).

If the area is exclusively used for day-care services, only fraction (1) applies.

In one case, the Tax Court held that utility rooms, such as a laundry and storage room and garage, may be counted as part of the day-care business area. The IRS had argued that because the children were not allowed in these areas, the space could not be considered as used for business. The Tax Court disagreed. The laundry room was used to wash the children’s clothes; the storage room and garage were used to store play items and equipment. Thus, the space was considered as used for child care even though the rooms were off limits to the children.

Storage space and inventory. If your home is the only location of a business selling products, you may deduct expenses allocated to space regularly used for inventory storage, including product samples, if the space is separately identifiable and suitable for storage. The space does not have to be used exclusively for business.

40.13 Write-Off Methods for Home Office Expenses

There are two ways in which you can figure your home office deduction: deduct your actual expenses or rely on an IRS-set standard deduction (simplified method). The two methods are explained below.

Simplified method. As long as the use of a portion of your home qualifies as a home office (40.12), you can choose to use a standard home office deduction (safe harbor) amount. For 2017, the amount is $5 per square foot for up to 300 of square feet of office space (maximum deduction is $1,500). Figure the deduction using a worksheet in the instructions for line 30 of Schedule C

.

You can decide whether to use the safe harbor method from year to year. In making your choice, keep in mind that the portion of the safe harbor amount that is not deductible because of the gross income limit (40.15) cannot be carried over and is lost forever. However, if in 2015 you deducted actual costs and switched to the simplified method for 2016 and for 2017 you are going back to deducting actual expenses, any unallowed expenses from 2015 may be deducted on your 2017 Form 8829.

When you opt for the safe harbor amount, no additional depreciation allowance can be claimed. If, in a future year you deduct your actual costs, ignore the year or years in which depreciation was not claimed and figure depreciation accordingly.

Actual expense method. For a qualifying home office (40.12) for which the actual expense method is used, deductible costs may include real estate taxes, mortgage interest, operating expenses (such as home insurance premiums and utility costs), and depreciation allocated to the area used for business. The deduction figured on Form 8829 may not exceed the net income derived from the business (40.15).

The deduction from Form 8829 is entered on Line 30 of Schedule C.

Expenses that affect only the business part of your home, such as repairs or painting of the home office only, are entered on Form 8829 as “direct” expenses. Expenses for running the entire home, including mortgage interest, taxes, utilities, and insurance, are deductible as “indirect” expenses to the extent of your business-use percentage (40.14).

Household expenses and repairs that do not benefit the office space are not deductible. However, a pro rata share of the cost of painting the outside of a house or repairing a roof is deductible. Costs of a new roof and landscaping are capital improvements according to the IRS, and so are not deductible immediately but may be recovered through depreciation.

If you install a security system for all your home’s windows and doors, the portion of your monthly maintenance fee that is allocable to the office area is a deductible operating expense. Furthermore, the business portion of your cost for the system is depreciable. Thus, if the office takes up 20% of your home (40.14) you may deduct, subject to an income limitation (40.15), 20% of the maintenance fee and a depreciation deduction for 20% of the cost.

Figuring depreciation. Even though a home is a residence, depreciation on a home office usually is figured as if it were commercial property using a 39-year recovery period (see Table 40-2). For depreciation purposes, the cost basis of the house is the lower of the fair market value of the house at the time you started to use a part of it for business or its adjusted basis, exclusive of the land. Only that part of the cost basis allocated to the office is depreciable. Form 8829 has a special section, Part III, for making this computation.

40.14 Allocating Expenses to Business Use

Allocate to home office use qualifying operating expenses (40.13) as follows: If the rooms are not equal or approximately equal in size, compare the number of square feet of space used for business with the total number of square feet in the home and then apply the resulting percentage to the total deductible expenses.

If all rooms in your home are approximately the same size, you may base the allocation on a comparison of the number of rooms used as an office to the total number of rooms.

Table 40-2 Nonresidential Real Property (39 years—Property placed in service after May 12, 1993)

|

Use the column for the month of taxable year placed in service. |

||||||||||||

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

10 |

11 |

12 |

|

|

Year |

||||||||||||

1 |

2.461% |

2.247% |

2.033% |

1.819% |

1.605% |

1.391% |

1.177% |

0.963% |

0.749% |

0.535% |

0.321% |

0.107% |

2–39 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

2.564 |

40 |

0.107 |

0.321 |

0.535 |

0.749 |

0.963 |

1.177 |

1.391 |

1.605 |

1.819 |

2.033 |

2.247 |

2.461 |

40.15 Business Income May Limit Home Office Deductions

Even if your home business use satisfies the deduction tests (40.12), deductions for the business portion (40.14) of utilities, maintenance, and insurance costs, as well as depreciation or rent deductions, may not exceed net business income after reducing the tentative profit from Schedule C by allocable mortgage interest, real estate taxes, and casualty deductions. To make sure that deductible expenses do not exceed income, the IRS requires you to use Form 8829. If you do not realize income during the year, no deduction is allowed. For example, you are a full-time writer and use an office in your home. You do not sell any of your work this year or receive any advances or royalties. Therefore, you may not claim a home office deduction for this year. See also the rules for writers and artists earlier in this chapter (40.9).

Part II of Form 8829 limits the deduction of home office expenses to net income derived from office use. You start with the tentative profit from Schedule C. If you sold your home during the year, increase the tentative profit by any net gain (or decrease tentative profit by any net loss) that is allocable to the office area and reported on Schedule D or Form 4797. The following expenses are listed first in Part II of Form 8829 for purposes of applying the income limit: Casualty losses affecting the residence, deductible mortgage interest, and real estate taxes. If there is income remaining after these expenses are subtracted from the Schedule C tentative profit, then home insurance premiums, repair and maintenance expenses for the residence, utility expenses, and rent are claimed against the remaining income. Depreciation is taken into account last, in Part III of Form 8829.

Business expenses not related to the home are deducted on the appropriate lines of Schedule C. For example, a salary paid to a secretary is deducted on Line 26 of Schedule C; the cost of depreciable business equipment used in your home is deducted on Line 13 of Schedule C.

The amount of real estate taxes, mortgage interest, or casualty losses not allocated to home office use may be claimed as itemized deductions on Schedule A.

40.16 Home Office for Sideline Business

You may have an occupation and also run a sideline business from an office in your home. The home office expenses are deductible on Form 8829 if the office is a principal place of operating the sideline business or a place to meet with clients, customers, or patients. Seethe deduction tests (40.12) and the income limit computation (40.15) for home office deductions. Managing rental property may qualify as a business.

Managing your own securities portfolio. Investors managing their own securities portfolios may find it difficult to convince a court that investment management is a business activity. According to Congressional committee reports, a home office deduction should be denied to an investor who uses a home office to read financial periodicals and reports, clip bond coupons, and perform similar activities. In one case, the Claims Court allowed a deduction to Moller, who spent about 40 hours a week at a home office managing a substantial stock portfolio. The Claims Court held these activities amounted to a business. However, an appeals court reversed the decision. According to the appeals court, the test is whether or not a person is a trader. A trader is in a business; an investor is not. A trader buys and sells frequently to catch daily market swings. An investor buys securities for capital appreciation and income without regard to daily market developments. Therefore, to be a trader, one’s activities must be directed to short-term trading, not the long-term holding of investments. Here, Moller was an investor; he was primarily interested in the long-term growth potential of stock. He did not earn his income from the short-term turnovers of stocks. He had no significant trading profits. His interest and dividend income was 98% of his income. Seethe discussion of trader expenses in 30.15.

40.17 Depreciation of Office in Cooperative Apartment

If your home office meets the tests discussed in 40.12, you may deduct depreciation on your stock interest in the cooperative. The basis for depreciation may be your share of the cooperative corporation’s basis for the building or an amount computed from the price you paid for the stock. The method you use depends on whether you are the first or a later owner of the stock.

You are the first owner. In figuring your depreciation, you start with the cooperative’s depreciable basis of the building. You then take your share of depreciation according to the percentage of stock interest you own. The cooperative can provide the details needed for the computation.

If space in the building is rented to commercial tenants who do not have stock interests in the corporation, the total allowable depreciation is reduced by the amount allocated to the space used by the commercial tenants.

You are a later owner of the cooperative’s stock. When you buy stock from a prior owner, your depreciable basis is determined by the price of your stock and your share of the co-op’s outstanding mortgage, reduced by amounts allocable to land and to commercial space.

40.18 Net Operating Losses (NOLs)

A loss incurred in your profession or unincorporated business is deducted from other income reported on Form 1040. If the loss exceeds your other income, you may have a net operating loss (NOL). An NOL can be used to offset income in other years. More specifically, you can usually carry the NOL back for two years and then forward for up to 20 years. A three-year carryback is allowed for an NOL attributable to casualty or theft losses, and for a qualified small business NOL attributable to a Presidentially declared disaster. A farming net operating loss may be carried back five years. Seethe instructions to Form 1045 for further details. A loss carried back to a prior year reduces income of that year and entitles you to a refund. A loss applied to a later year reduces income for that year. You may elect to carry forward your 2017 loss for 20 years, foregoing the carryback (40.22).

The rules below apply not only to self-employed individuals, farmers, and professionals, but also to individuals whose casualty losses exceed income, stockholders in S corporations, and partners whose partnerships have suffered losses. Each partner claims his or her share of the partnership loss.

Carryover of loss from prior year to 2017. If you had a net operating loss in an earlier year that is being carried forward to 2017, the loss carryover is reported as a minus figure on Line 21 of Form 1040. You must attach a detailed statement showing how you figured the carryover.

Change in marital status. If you incur a net operating loss while single but are married filing jointly in a carryback or carryforward year, the loss may be used only to offset your own income on the joint return.

If the net operating loss was claimed on a joint return and in the carryback or carryforward year you are not filing jointly with the same spouse, only your allocable share of the original loss may be claimed; seeIRS Publication 536.

Passive activity limitation. Losses subject to passive activity rules of Chapter 10 are not deductible as net operating losses. However, losses of rental operations coming within the $25,000 allowance (10.2) may be treated as net operating loss if the loss exceeds passive and other income.

40.19 Your Net Operating Loss

A net operating loss is generally the excess of deductible business expenses over business income. The net operating loss may also include the following losses and deductions:

- Casualty and theft losses, even if the property was used for personal purposes; see Chapter 18.

- Expenses of moving to a new job location; see Chapter 12.

- Deductible job expenses such as travel expenses, work clothes, costs, and union dues (19.3).

- Your share of a partnership or S corporation operating loss.

- Loss on the sale of small business investment company (SBIC) stock.

- Loss incurred on Section 1244 stock.

An operating loss may not include:

- Net operating loss carryback or carryover from any year.

- Capital losses that exceed capital gain.

- Excess of nonbusiness deductions over nonbusiness income plus nonbusiness net capital gain.

- Deductions for personal exemptions.

- A self-employed person’s contribution to a qualified retirement plan or SEP.

- An IRA deduction.

Income from other sources may eliminate or reduce your net operating loss.

40.20 How To Report a Net Operating Loss

You compute your net operating loss deduction on Schedule A of Form 1045 (40.21). You start with adjusted gross income and personal deductions shown on your tax return. As these figures include items not allowed for net operating loss purposes, you follow the line-by-line steps of Schedule A (Form 1045) to eliminate them. That is, you reduce the loss by the nonallowed items such as deductions for personal exemptions, net capital loss, and nonbusiness deductions exceeding nonbusiness income. The Example at the end of this section illustrates the steps in the schedule.

Adjustment for nonbusiness deductions. Nonbusiness deductions that exceed nonbusiness income may not be included in a net operating loss deduction. Nonbusiness deductions include deductions for IRA and qualified retirement plans and itemized deductions such as charitable contributions, interest expense, state taxes, and medical expenses. Do not include in this non-allowed group deductible casualty and theft losses, which for net operating loss purposes are treated as business losses. If you do not claim itemized deductions in the year of the loss, you must treat the standard deduction as a nonbusiness deduction.

Nonbusiness income is income that is not from a trade or business—such as dividends, interest, and annuity income. The excess of nonbusiness capital gains over nonbusiness capital losses is also treated as part of nonbusiness income that offsets nonbusiness deductions.

At-risk loss limitations. The loss used to figure your net operating loss deduction is subject to the at-risk rules (10.17). If part of your investment is in nonrecourse loans or is otherwise not at risk, you must compute your deductible loss on Form 6198, which you attach to Form 1040. The deductible loss from Form 6198 is reflected in the income and deduction figures you enter on the Form 1045 schedule to compute your net operating loss deduction.

Reporting NOLs. NOLs carried forward from prior years are reported on Line 21 of Form 1040 as “other income.” The NOL is entered as a negative amount. When amending prior returns to account for an NOL carryback, the NOL is entered as a negative amount.

40.21 How To Carry Back Your Net Operating Loss