Chapter 5

Reporting Property Sales

Long-term capital gains are generally taxed at lower rates than those imposed on ordinary income. Depending on your taxable income, some or all of your long-term capital gains may qualify for a 0% rate and thus completely avoid tax (5.3). If the 0% rate does not apply, your long-term gains are subject to maximum rates of 15% or 20% depending on your income, or, for certain assets, a maximum rate of 25% or 28% (5.3), but regular tax rates apply if they result in a lower tax than the maximum rate.

If you sell property and will receive payments in a year (or years) after the year of sale, you may report the sale as an installment sale on Form 6252 and spread the tax on your gain over the installment period (5.21).

Sales of business assets and depreciable rental property are reported on Form 4797. Most assets used in a business are considered Section 1231 assets, and capital gain or ordinary loss treatment may apply depending upon the result of a netting computation made on Form 4797 for all such assets sold during the year (44.8).

Special types of sale situations are detailed in other chapters.

See Chapter 29 for the exclusion of gain on the sale of a principal residence.

See Chapter 32 for figuring gain or loss on the sale of mutual fund shares.

See Chapter 6 for tax-free exchanges of property.

See Chapter 30 for sales of stock dividends, stock rights, wash sales, short sales, and sales by traders in securities.

5.1 General Tax Rules for Property Sales

- Property is classified according to its nature and your purpose for holding it; see 5.2, Table 5-1, and holding period rules at 5.3 and 5.9–5.12.

- Sales of capital assets must generally be reported on Form 8949, with Part I used for short-term gains and losses and Part II for long-term gains and losses (5.8). However, in some cases you do not need Form 8949 and may report your transactions directly on Schedule D; see 5.8. If you file Form 8949, you must check a box to indicate whether you received a Form 1099-B from a broker showing your basis in securities sold. If you are reporting more than one sale of securities, you may need to file multiple Forms 8949 depending on how basis was reported on Form 1099-B. Total amounts for sales price and basis are transferred from Form 8949 to Schedule D of Form 1040. On Schedule D you net short-term and long-term transactions to figure your net gain or loss for the year and, if you have net long-term gain, you are directed to the appropriate IRS worksheet for computing your tax liability taking into account the favorable capital gain rates, as discussed in the next paragraph. Filing Form 8949 or Schedule D may not be necessary if your only capital gains are from a mutual fund or REIT (32.8).

- If you sell property at a gain, the applicable tax rate depends on the classification of the property (see Table 5-1) and, in the case of capital assets, the period you held the property before sale. A capital gain is long term if you held the asset for more than one year, short-term if you held it for one year or less. Short-term capital gains that are not offset by short- or long-term losses are subject to regular income tax rates.

If you have net capital gain for the year (net long-term gain over net short-term loss if any), your gains are subject to favorable capital gain rates. Depending on your taxable income and the amount and source of your long-term gains, the gains may be completely tax free under the 0% rate or subject to a maximum rate of 15%, 20%, 25%, or 28% where that maximum rate is less than the otherwise applicable regular tax rate (5.3).

If you do not have 28% rate gains or unrecaptured Section 1250 gains subject to a maximum 25% rate, you compute your tax liability taking into account the 0%, 15% and 20% capital gain rates on the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet in the Form 1040 instructions. If you have either 28% gain or unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, use the Schedule D Tax Worksheet in the Schedule D instructions to compute your tax liability.

- Loss deductions are allowed on the sale of investment and business property but not personal assets; see Table 5-1. Capital loss deductions in excess of capital gains are limited to $3,000 annually, $1,500 if married filing separately; see the details on the capital loss limitations later in this Chapter (5.4 – 5.5).

5.2 How Property Sales Are Classified and Taxed

The tax treatment of gains and losses is not the same for all types of property sales. Tax reporting generally depends on your purpose in holding the property, as shown in Table 5-1.

When capital gain or loss treatment does not apply. Certain sales do not qualify for capital gain or loss treatment. Business inventory and property held for sale to customers are not capital assets. Depreciable business and rental property are not capital assets, but you may still realize capital gain after following a netting computation for Section 1231 assets (44.8).

Although assets held for personal use, such as a car or home, are technically capital assets, you may not deduct a capital loss on their sale.

Certain other assets held for investment or personal use are excluded by law from the capital asset category. These include copyrights, literary or musical compositions, letters, memoranda, or similar property that: (1) you created by your personal efforts or (2) you acquired as a gift from the person who created the property or for whom the property was prepared or produced.

Although musical compositions and copyrights in musical works that you personally created (or you acquired as a gift from the creator) are generally excluded from the capital asset category, you can make an election on a timely filed (including extensions) Form 8949 for the year the musical composition or copyright is sold to treat the sale as a sale of a capital asset.

Also excluded from the capital asset category are letters, memoranda, or similar property prepared or produced for you by someone else. Finally, U.S. government publications obtained from the government for free or for less than the normal sales price do not qualify as capital assets.

Table 5-1 Capital or Ordinary Gains and Losses From Sales and Exchanges of Property

| If you sell— | Your gain is— | Your loss is— | Reported on— |

| Stocks, mutual funds, bonds, land, art, gems, stamps, and coins held for investment are capital assets. | Capital gain. Holding period determines short-term or long-term gain treatment (5.3). Security traders may report ordinary income and loss under a mark-to-market election. | Capital loss. Capital losses are deductible from capital gains with only $3,000 of any excess deductible from ordinary income, $1,500 if married filing separately (5.4). | Form 8949 and Schedule D (5.8). However, if the only amounts you have to report on these forms are mutual fund capital gain distributions, then you may report the distributions directly on Form 1040A or Form 1040 (Table 32-1). Form 4797 for gains and losses of a trader in securities who makes the mark-to-market election (30.15). |

| Business inventory held for sale to customers. Also, accounts or notes receivable acquired in the ordinary course of business or from the sale of inventory or property held for sale to customers, or acquired for services as an employee. | Ordinary income. Such property is excluded by law from the definition of capital assets. | Ordinary loss. Ordinary loss is not subject to the $3,000 deduction limit imposed on capital losses. However, passive loss restrictions, discussed in Chapter 10, may defer the time when certain ordinary losses are deductible. | Schedule C if self-employed; Schedule F if a farmer; Form 1065 for a business operated as a partnership; Form 1120 or 1120-S for an incorporated business. |

| Depreciable residential rental property or trucks, autos, computers, machinery, fixtures, or equipment used in your business. | Capital gain or ordinary income. Section 1231 determines whether gain is taxable as ordinary income or capital gain (44.8). Where an asset such as an auto or residence is used partly for personal purposes and partly for business or rental purposes, the asset is treated as two separate assets for purposes of figuring gain or loss (44.9). |

Ordinary loss if there is a net Section 1231 loss (44.8). However, if you are considered to be an investor in a passive activity, see 10.12 and 10.13. | Form 4797 for Section 1231 transactions. |

| Personal residence, car, jewelry, furniture, art objects, and coin or stamp collection held for personal use. | Capital gain. See the holding period rules that determine short-term or long-term gain treatment and the preferential tax rates applied to net long-term capital gains (5.3). Where an asset such as an auto or residence is used partly for personal purposes and partly for business or rental purposes, the asset is treated as two separate assets for purposes of figuring gain or loss (44.9). All or part of a profit from a sale of a principal residence may be excludable from income; see Chapter 29. |

Not deductible. Losses on sales of assets held for personal use are not deductible although profits are taxable. | Form 8949 and Schedule D |

Stock is generally treated as a capital asset, but losses on Section 1244 stock of qualifying small businesses may be claimed as ordinary losses on Form 4797, rather than on Schedule D as capital losses, which are subject to the $3,000 deduction limit ($1,500 if married filing separately) (30.11).

Traders in securities may elect to report their sales as ordinary income or loss rather than as capital gain or loss (30.14).

Small business stock deferral. Taxable gains from the sale of publicly traded securities may be postponed if you roll over the proceeds to stock or a partnership interest in a SSBIC (specialized small business investment company) (5.7).

Small business/empowerment zone business stock exclusion. Gains on the sale of qualifying small business stock held for more than five years qualify for an exclusion (5.7).

Like-kind exchanges of business or investment property. Exchanges of like-kind business or investment property are subject to special rules that allow gain to be deferred, generally until you sell the property received in the exchange (6.1). When property received in a tax-free exchange is held until death, the unrecognized gain escapes income tax forever because the basis of property in the hands of an heir is generally the fair market value of the property at the date of death (5.17). A loss on a like-kind exchange is not deductible.

Stock redemption allocation to covenant not to compete. If you sell company stock back to your employer and you are subject to a covenant not to compete with the company for a period of time, any portion of the purchase price for the stock that is allocated to the covenant in the contract is taxed to you as ordinary income and not capital gain.

5.3 Capital Gains Rates and Holding Periods

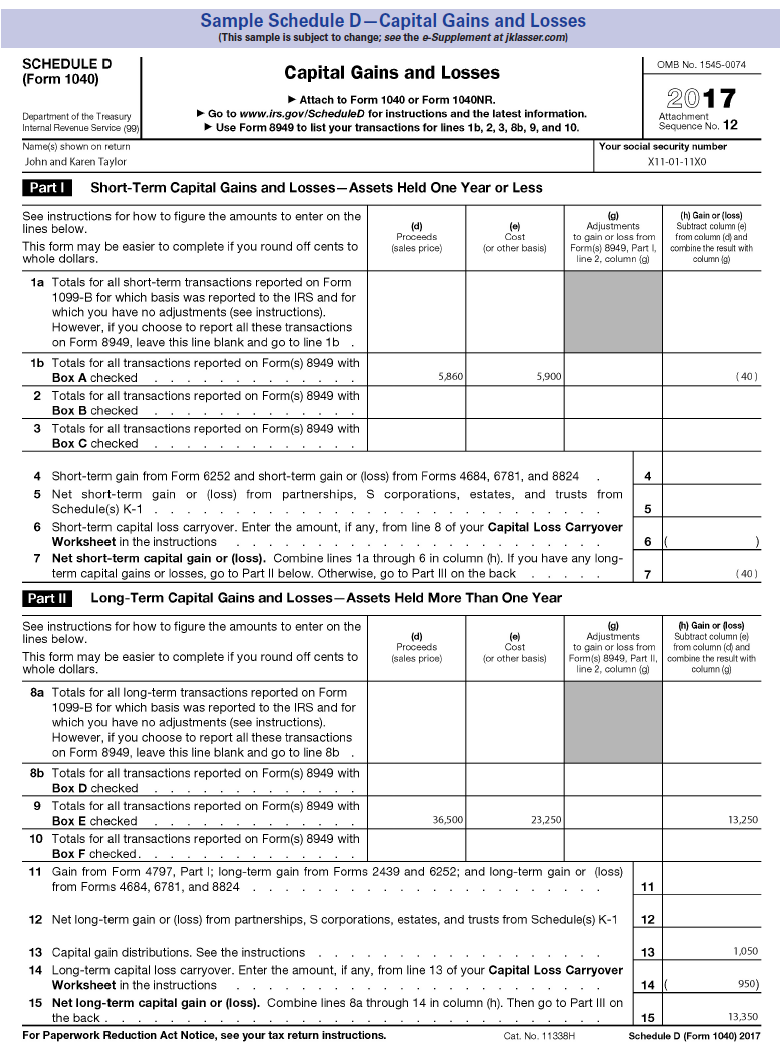

Form 8949 is used for reporting sales of capital assets. On Form 8949, you separate your sales into short-term and long-term categories. Assets held for one year or less are in the short-term category and assets held for more than one year are in the long-term category. The totals from Form 8949 are entered on Schedule D (Form 1040). See the Example in 5.8, which includes filled-in samples of Form 8949 and Schedule D.

The computation of tax liability using the favorable long-term capital gain rates is not made directly on Schedule D, but on worksheets in the IRS instructions. Mutual fund and REIT investors may be able to apply the favorable rates on the “Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet” included in the Form 1040 or Form 1040A instructions, without having to file Form 8949 or Schedule D (Table 32-1).

Held for a year or less. Details for sales of capital assets held for a year or less are reported in Part I of Form 8949 unless you are able to report them directly on Schedule D and you choose to do so. The total sales prices and total cost basis shown on Form 8949 for short-term transactions, along with any adjustments for such transactions, are transferred to Part I of Schedule D, where the net short-term gain or loss for the year is determined. A net short-term capital gain is subject to regular tax rates. On Part III of Schedule D, a net net short-term loss from Part I offsets a net long-term gain, if any, from Part II of Schedule D. A net short-term loss in excess of net long-term gain is deductible up to the $3,000 capital loss limit (5.4).

Held for more than a year. Details for sales of capital assets held for more than a year are reported in Part II of Form 8949, unless you are able to report them directly on Schedule D and you choose to do so. The total sales prices and total cost basis for all the long-term transactions shown on form 8949, along with any adjustments for such transactions, are transferred to Part II of Schedule D, where the net long-term gain or loss for the year is determined. A net long-term capital loss offsets a net short-term gain, if any, from Part I of Schedule D. If you have a net long-term capital gain on Part II and also a net short-term capital loss on Part I of Schedule D, the short-term loss offsets the net long-term gain. The offsets are made on Part III of Schedule D . If the net short-term loss exceeds the net long-term gain, the excess short-term loss is deductible up to the $3,000 capital loss limit (5.4). If you have a net long-term gain in excess of a net short-term capital loss (if any), the excess is called net capital gain and it is this amount to which the favorable capital gain rates may apply, as discussed below.

Reduced Rates on Net Capital Gain

Tax liability must be computed on IRS worksheets to benefit from capital gain rates. Net capital gain (net long-term capital gain in excess of net short-term capital loss) is subject to maximum tax rates that are generally lower than the rates applied to ordinary income. Qualified dividends (4.2) are subject to the same favorable rates as net capital gain.

If you have a net capital gain for 2017 that does not include a 28% rate gain or unrecaptured Section 1250 gain (see below), you should compute your 2017 regular tax liability on the “Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet” in the IRS instructions for Line 44 of Form 1040. On the Worksheet, you take into account the favorable capital gain rates, as applicable, and the regular tax rates on the rest of your taxable income. The Worksheet must be used to figure your regular tax liability instead of the regular IRS Tax Table (22.2) or Tax Computation Worksheet (22.3) in order to benefit from the maximum capital gain rates. The tax liability from the Worksheet is entered on Line 44 of Form 1040.

If you have a net capital gain that includes either a net 28% rate gain or unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, you must compute your tax liability on the “Schedule D Tax Worksheet” in the Schedule D instructions to benefit from the maximum capital gain rates applicable to those assets. The tax liability from the Worksheet is entered on Line 44 of Form 1040.

On both the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet and the Schedule D Tax Worksheet, net capital gain eligible for the maximum capital gain rates is reduced by any gains that you elect to treat as investment income on Form 4952 to increase your itemized deduction for investment interest (15.10).

The 0%, 15%, and 20% rates. Qualified dividends (4.1) and net capital gain (net long-term gains in excess of net short-term losses) are generally subject to the 0% or 15% capital gain rate on the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet or the Schedule D Tax Worksheet.

The 20% rate may apply if your taxable income exceeds the threshold for the 39.6% tax bracket. This means that for 2017 returns, the 20% rate cannot apply unless your taxable income exceeds $418,400 if single, $444,550 if a head of household, $470,700 if married filing jointly, or $235,350 if married filing separately. Even if taxable income does exceed the threshold, your qualified dividends and net capital gain are not necessarily taxed at the 20% rate. You may still be able to benefit from the 0% and 15% rates, provided that most of your taxable income is qualified dividends and net capital gain rather than ordinary income.

Note: The 0%, 15% and 20% rates do not apply to any portion of net capital gain that is 28% rate gain (from collectibles and Section 1202 exclusion) or unrecaptured Section 1250 gain (from post-1986 real estate depreciation); these are subject, respectively, to maximum rates of 28% and 25% as discussed below. Also keep in mind that if your MAGI exceeds the threshold for the 3.8% tax on net investment income (28.3), the effective rate on some or all of your gains (depending on MAGI) will be increased by 3.8%.

Can Your Gains/Dividends Avoid Tax Completely Under the 0% rate? You qualify for the 0% rate if your top tax bracket is 10% or 15%. This means that if your taxable income is within the 10% and 15% brackets, and none of your long-term capital gains are 28% rate gains or unrecaptured Section 1250 gains, then all of your gains and qualified dividends are tax free under the 0% rate. On 2017 returns, the top of the 15% bracket is taxable income of $37,950 for single taxpayers and married persons filing separately, $50,800 for heads of household, and $75,900 for married persons filing jointly and qualifying widows/widowers. Thus, if your 2017 taxable income is no more than the applicable amount for your filing status, all of your net capital gain and qualified dividends are tax free.

Perhaps surprisingly, individuals with a top bracket higher than 15% may also be able to benefit from the 0% rate. The extent to which higher-bracket taxpayers can benefit from the 0% rate depends on their taxable income, their filing status, which determines the top of their 15% bracket, and the amount of their qualified dividends and net capital gain. On the IRS worksheets used to figure tax liability (the “Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet,” or the “Schedule D Tax Worksheet,” as applicable), your taxable income is reduced by your qualified dividends and net capital gain (other than 28% rate gain and unrecaptured Section 1250 gain). The resulting amount is treated as ordinary income and if it is less than the top of your 15% bracket, your qualified dividends and capital gains (other than 28% rate gain and unrecaptured Section 1250 gain) are tax free under the 0% rate to the extent that they “fill up” the rest of the 15% bracket.

For example, if you are single and for 2017 you have taxable income of $47,200, including $2,000 of qualified dividends and $12,000 of eligible net capital gain, your ordinary income for purposes of the 2017 worksheet computation is $33,200 ($47,200− $14,000), and since the top of the 15% bracket for single taxpayers is taxable income of $37,950, there is still $4,750 left within the 15% bracket ($37,950-$33,200). The 0% rate applies to $4,750 of your gains/dividends, and the $9,250 balance ($14,000 − $4,750) is taxed at 15%. Also see Example 2 below for how a married couple filing jointly with a top bracket exceeding 15% can benefit from the 0% rate.

If the ordinary income is equal to or more than the top of your 15% bracket ($37,950, $50,800, or $75,900, as applicable), the 0% rate will not apply to any of your qualified dividends and eligible gains; see Example 3 below.

Caution: Children subject to the kiddie tax. If your child is subject to the kiddie tax (24.2) and has net investment income exceeding $2,100 for 2017, the excess is treated as your own income and subject to your tax rate. If the excess includes net capital gains and qualified dividends, your maximum capital gain rate will apply if it is higher than your child’s rate. Even if the 0% rate would apply to your child’s 2017 gains and dividends based on his or her taxable income, the 0% rate will not be available unless your rate is also 0% when you make the kiddie tax computation on Form 8615.

28% rate gains from sales of collectibles and small business or empowerment zone business stock eligible for exclusion. Long-term gains on the sale of collectibles such as art, antiques, precious metals, gems, stamps, and coins are considered “28% rate gains.” If you sell qualified small business stock eligible for an exclusion (Section 1202 exclusion (5.7)), the taxable portion of the gain is also treated as a 28% rate gain. The 28% rate transactions are reported first in Part II (long-term capital gains and losses) of Form 8949 and then transferred to Schedule D, unless you are able to directly report them on Schedule D. If taking into account all your transactions you have both a net long-term capital gain for the year and a net capital gain (excess of net long-term gain over net short-term loss if there is one), you have to complete the “28% Rate Gain Worksheet” in the Schedule D instructions. On the Worksheet, 28% rate gains are reduced by any long-term collectibles losses and net short-term capital loss for the current year, and any long-term capital loss carryover from the previous year.

A net 28% rate gain from the 28% Rate Gain Worksheet is entered on Line 18 of Schedule D and then on the “Schedule D Tax Worksheet” in the Schedule D instructions. The Schedule D Tax Worksheet is used to figure the regular tax on all of your taxable income (not just on your net capital gain and qualified dividends). The effect of the worksheet computation is to tax 28% rate gain at either the 28% rate or at the regular rates on ordinary income, whichever results in the lower tax.

The tax figured on the “Schedule D Tax Worksheet” is entered on Line 44 of Form 1040.

Unrecaptured Section 1250 gain on sale of real estate. Long-term gain that is attributable to real estate depreciation is not taxable at the 0%, 15% or 20% capital gain rate. Gain attributable to pre-1987 depreciation may be recaptured as ordinary income (44.2). To the extent your gain is attributable to post-1986 depreciation, the gain is considered “unrecaptured Section 1250 gain.” Unrecaptured Section 1250 gain is figured on the “Unrecaptured Section 1250 Gain Worksheet” in the Schedule D instructions. The worksheet computation reduces unrecaptured Section 1250 gain by a net loss, if any, from the 28% rate group.

The net unrecaptured Section 1250 gain from the worksheet is entered on Line 19 of Schedule D and then on the Schedule D Tax Worksheet, where tax liability on all of your taxable income is computed. The effect of the computation on the Schedule D Tax Worksheet is to tax unrecaptured Section 1250 gain at either a 25% rate or at the regular rates on ordinary income, whichever results in the lower tax. The tax figured on the Schedule D Tax Worksheet is entered on Line 44 of Form 1040.

Capital gain distributions from mutual funds. Your fund will report long-term capital gain distributions on Form 1099-DIV. See Chapter 32 for details on how to report the distributions.

Capital gain from Schedule K-1. Net capital gain or loss from a pass-through entity such as a partnership, S corporation, estate, or trust is reported to you on a Schedule K-1. Report net short-term gain or loss in Part I of Schedule D and net long-term gain or loss in Part II of Schedule D.

5.4 Capital Losses and Carryovers

Capital losses are fully deductible against capital gains on Schedule D, and if losses exceed gains, you may deduct the excess from up to $3,000 of ordinary income on Form 1040. Net losses over $3,000 are carried over to future years. On a joint return, the $3,000 limit applies to the combined losses of both spouses (5.5). The $3,000 limit is reduced to $1,500 for married persons filing separately.

Although qualified dividends (4.1) are subject to the same rates as net capital gain, the dividends are not reported as long-term gains on Part II of Form 8949 or Schedule D and thus are not offset by capital losses in determining whether you have a net capital gain or loss for the year.

In preparing your 2017 Schedule D, remember to include any capital loss carryovers from your 2016 return. Use the carryover worksheet in the 2017 Schedule D instructions for figuring your short-term and long-term loss carryovers from 2016 to 2017. Short-term carryover losses are entered on Line 6 of Part I and long-term carryover losses are entered on Line 14, Part II.

Losses from wash sales not deductible. You cannot deduct a loss from a wash sale of stock or securities unless you are a dealer in those securities. A wash sale occurs if within 30 days before or after your sale at a loss, you acquire substantially identical securities or purchase an option to acquire such securities (30.6). A disallowed wash sale loss should be reported in Box 1g of Form 1099-B.

Report a wash sale on Part 1 (short-term) or Part II (long-term) of Form 8949 and enter code “W” in column (f) to identify the wash sale loss. In column (g) enter the disallowed loss as a positive amount.

Death of taxpayer cuts off carryover. If an individual dies and on his or her final income tax return net capital losses, including prior year carryovers, exceed the $3,000 or $1,500 limit, the excess may not be deducted by the individual’s estate. If the deceased individual was married, his or her unused individual losses may not be carried over by the surviving spouse (5.5).

5.5 Capital Losses of Married Couples

On a joint return, the capital asset transactions of both spouses are combined and reported on one Schedule D. A carryover loss of one spouse may offset capital gains of the other spouse on a jointly filed Schedule D. Where you and your spouse separately incur net capital losses, $3,000 is the maximum capital loss deduction that may be claimed for the combined losses on your joint return. This limitation may not be avoided by filing separate returns. If you file separately, the deduction limit for each return is $1,500. Neither of you may deduct any of the other’s losses on a separate return.

Death of a spouse. The IRS holds that if a capital loss is incurred by a spouse on his or her own property and that spouse dies, the loss may be deducted only on the final return for the spouse (which may be a joint return). The surviving spouse may not claim any unused loss carryover on a separate return and the decedent’s estate may not deduct the unused carryover.

5.6 Losses May Be Disallowed on Sales to Related Persons

A loss on a sale to certain related taxpayers may not be deductible, even though you make the sale at an arm’s-length price, the sale is involuntary (for example, a member of your family forecloses a mortgage on your property), or you sell through a public stock exchange and related persons buy the equivalent property; see Examples 1 and 2 in this section.

If you have a nondeductible related party loss, identify it by entering code “L” in column (f) of Form 8949 (Part I or Part II as appropriate), and enter it as a positive amount in column (g).

Related parties. Losses are not allowed on sales between you and your brothers or sisters (whether by the whole or half blood), parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, children, grandchildren, or great-grandchildren. Furthermore, no loss may be claimed on a sale to your spouse; the tax-free exchange rules discussed in Chapter 6 apply (6.7).

A loss is disallowed where the sale is made to your sister-in-law, as nominee of your brother. This sale is deemed to be between you and your brother. But you may deduct the loss on sales to your spouse’s relative (for example, your brother-in-law or spouse’s step-parent) even if you and your spouse file a joint return.

The Tax Court has allowed a loss on a direct sale to a son-in-law. In a private ruling, the IRS allowed a loss on a sale of a business to a son-in-law where it was shown that his wife (the seller’s daughter) did not own an interest in the company. Losses have been disallowed upon withdrawal from a joint venture and from a partnership conducted by members of a family. Family members have argued that losses should be allowed where the sales were motivated by family hostility. The Tax Court ruled that family hostility may not be considered; losses between proscribed family members are disallowed in all cases.

Losses are barred on sales between an individual and a controlled partnership or controlled corporation (where that individual owns more than 50% in value of the outstanding stock or capital interests). In calculating the stock owned, not only must the stock held in your own name be taken into account, but also that owned by your family. You also add (1) the proportionate share of any stock held by a corporation, estate, trust, or partnership in which you have an interest as a shareholder, beneficiary, or partner; and (2) any other stock owned individually by your partner.

Losses may also be disallowed in sales between controlled companies, a trust and its creator, a trust and a beneficiary, a partnership and a corporation controlled by the same person (more than 50% ownership), or a tax-exempt organization and its founder. An estate and a beneficiary of that estate are also treated as related parties, except where a sale is in satisfaction of a pecuniary bequest. Check with your tax counselor whenever you plan to sell property at a loss to a buyer who may fit one of these descriptions.

Related buyer’s resale at profit. Sometimes, the disallowed loss may be saved. When you sell to a related party who resells the property at a profit, he or she gets the benefit of your disallowed loss. Your purchaser’s gain is not taxed to the extent of your disallowed loss; see Example 4 below.

5.7 Deferring or Excluding Gain on Sale of Small Business Stock Investment

To encourage investments in certain “small” businesses, the tax law provides special tax benefits.

Rollover of gain from sale of qualified small business stock (Section 1045 rollover). Gain on the sale of qualifying small business stock (QSB stock) held for more than six months may be rolled over tax free to other QSB stock. The rollover must be made within 60 days of the sale. To qualify as QSB stock, the stock must be stock in a C corporation (not S corporation) that was originally issued after August 10, 1993. The gross assets of the corporation must have been no more than $50 million at all times after August 9, 1993, and before issuance of the stock, as well as immediately after issuance of the stock. You must have acquired the stock at its original issue, as a gift or inheritance from a qualifying transferor, or in a conversion of other qualified stock. The C corporation must have met an active business requirement for substantially the entire time you held the stock. The active business test generally requires that the C corporation used at least 80% of its assets (by value) in the active conduct of at least one qualified trade or business, which is any business not specifically excluded by the law. However, many types of businesses are excluded from the “qualified” category. These are: (1) service businesses in the fields of health, law, accounting, financial services, brokerage, consulting, actuarial science, engineering, architecture, performing arts, or sports, (2) any business whose principal asset is the skill or reputation of one or more of its employees, (3) restaurants, hotels, motels or similar businesses, (4) insurance, banking, financing, leasing or similar businesses, (5) farming, and (6) oil, gas, and extraction businesses that can use percentage depletion. See the Schedule D instructions and IRS Publication 550 for further QSB requirements.

If the sale proceeds exceed the cost of the replacement stock, your gain is taxed to the extent of the difference. The basis of the replacement stock is reduced by the deferred gain.

To elect deferral, report the sale on Part I (short-term gain) or Part II (long-term gain) of Form 8949. Enter code “R” in column (f) and enter the deferred gain as a negative adjustment in column (g).

Generally, the election to defer gain must be made by the due date or extended due date for your return. If you timely file your original return without the election, the election may be made on an amended return filed no more than six months after the original due date.

Exclusion of gain on small business stock (Section 1202 exclusion). If you sell qualified small business stock (QSB stock) after holding it more than five years, 50%, 75% or even 100% of the gain is excludable from your income, depending on when you acquired it. For exclusion purposes, QSB stock is defined the same way as for purposes of the Section 1045 rollover rules discussed above.

If you acquired the QSB stock before February 18, 2009, 50% of the gain is excludable from income. If you acquired the QSB stock after February 17, 2009, and before September 28, 2010, the exclusion is 75%. The 100% exclusion applies to the gain on a sale of QSB stock acquired after September 27, 2010, if the over-five-year holding period was met.

If you qualify for the exclusion, report the sale in Part II of Form 8949. Enter code “Q” in column (f) and enter the excluded amount as a negative adjustment in column (g). If you have a net capital gain (net long-term gain in excess of net short-term loss, if any) on Schedule D, include the taxable portion of the QSB stock gain on the 28% Rate Gain Worksheet in the Schedule D instructions (5.3).

There is an annual and lifetime limit on the Section 1202 exclusion for QSB stock from any one issuer. The amount of gain from any one issuer that is eligible for the exclusion in 2017 is limited to the greater of (1) 10 times your basis in the qualified stock that you disposed of during 2017, or (2) $10 million ($5 million if married filing separately) minus any gain on stock from the same issuer that you excluded in prior years.

Will there be a 60% exclusion for empowerment zone business stock sold in 2017? A 60% exclusion (instead of 50%) applied to gain on sales before 2017 of QSB stock acquired after December 21, 2000, and before February 18, 2009, in a corporation that qualified as an empowerment zone business during substantially all the time you held the stock. However, the law authorizing the designation of an area as an empowerment zone expired at the end of 2016, and without an extension of the law, there will be no empowerment zone designations in effect for 2017. This would mean that for 2017 sales of stock acquired before February 18, 2009, that otherwise qualify for the QSB exclusion, the exclusion would be 50%. See the e-Supplement at jklasser.com for an update, if any, on whether the empowerment zone rules are extended beyond 2016, thereby allowing an increased exclusion of 60% for sales that otherwise would be subject to the 50% exclusion. This issue is irrelevant for QSB stock acquired after February 17, 2009, since on a sale of such stock, the exclusion is either 75% or 100% as discussed earlier.

Will rollover of gain be allowed for empowerment zone business stock sold in 2017? As noted above, the law authorizing the designation of an area as an empowerment zone expired at the end of 2016. Without an extension of the law, 2017 sales will not qualify for a rollover provision that allows gains on sales of qualifying empowerment zone assets held over one year to be deferred if a replacement asset is bought in the same empowerment zone during the 60-day period beginning on the date of the sale. See the e-Supplement at jklasser.com for an update, if any, on an extension of the law allowing empowerment zone designations.

Rollover from publicly traded securities to SSBIC. You may be able to defer taxable gain on the sale of publicly traded securities provided the sale proceeds are rolled over within 60 days into common stock or a partnership interest in a “specialized small business investment company,” or SSBIC. An SSBIC is a partnership or corporation licensed by the Small Business Administration to invest in small businesses that are owned by socially or economically disadvantaged individuals. Subject to the deferrable limit, the entire gain is deferrable if the cost of your SSBIC stock or partnership interest is at least equal to the sale proceeds. If the SSBIC investment is less than the sale proceeds, your gain is taxed to the extent of the difference. The deferred gain reduces the basis of your SSBIC stock or partnership interest.

There is an annual and lifetime limit on the deferrable gain. The deferrable limit each year is limited to the smaller of (1) $50,000, or $25,000 if you are married filing separately, or (2) $500,000, or $250,000 if married filing separately, minus any gains deferred for all prior years.

To elect deferral, you must report the sale on Form 8949. In column ( f ), enter code “R” and in column (g) enter the deferred gain as a negative adjustment. Also attach an explanation detailing the SSBIC investment and how you figured the deferred gain.

5.8 Reporting Capital Asset Sales on Form 8949 and on Schedule D

You generally must report sales and other dispositions of capital assets on Form 8949, but in some cases (see below), you can report your transactions directly on Schedule D without having to report them on Form 8949. You report on Form 8949/Schedule D sales of securities, redemptions of mutual fund shares, worthless personal loans, sales of stock rights and warrants, sales of land held for investment, and sales of personal residences where part of the gain does not qualify for the home sale exclusion (29.1).

Although capital gain distributions from mutual funds and REITs are generally reported as long-term capital gains on Line 13 of Schedule D, investors who receive such distributions but have no other capital gains or losses to report may generally report the distributions directly on Form 1040 or 1040A without having to file Schedule D; see 32.8 for details.

The favorable maximum capital gain rates (5.3) apply to net capital gain (net long-term capital gain in excess of net short-term capital loss) from Schedule D, and also to qualified dividends (4.2). Although qualified dividends are subject to the same favorable maximum rates as net capital gain, they are not entered as long-term gains in Part II of Schedule D. The favorable rates are applied to qualified dividends when tax liability is computed on either the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet or the Schedule D Tax Worksheet. You must use the applicable worksheet to obtain the benefit of the favorable maximum capital gain rates for your net capital gain and qualified dividends. The Schedule D Tax Worksheet in the Schedule D instructions is used only if you have a net 28% rate gain or unrecaptured Section 1250 gain (5.3). If you do not have a net 28% rate gain or unrecaptured Section 1250 gain, use the Qualified Dividends and Capital Gain Tax Worksheet in the Form 1040 instructions.

Basis of “covered” securities reported on Form 1099-B. When you sell a “covered” security, the broker must report your basis in the security in Box 1e of the Form 1099-B sent to you and the IRS. Box 3 should be checked where the basis is being reported to the IRS. In general, a covered security is stock acquired after 2010, mutual fund shares acquired after 2011, stock acquired after 2011 in a dividend reinvestment plan eligible for the average basis method, futures contracts entered into after 2013, certain bonds acquired after 2013 (described in the Form 1099-B instructions) and certain bonds acquired after 2015, including variable rate and inflation-indexed bonds (see further details in the Form 1099-B instructions).

Even if you sell a “noncovered” security, the broker may report basis in Box 1e and if so, Box 3 should be checked to indicate that basis is being reported to the IRS. For a noncovered security, Box 5 should have been checked whether or not basis is reported. If the broker does not check Box 5 for a noncovered security, penalties can be assessed against the broker for not correctly completing Boxes 1b (date acquired), 1e(basis), 1f(accrued market discount), 1g (disallowed wash sale loss) and 2 (short-term or long-term gain or loss or ordinary income).

If during the year you have sold more than one security with the same broker, each transaction is generally reported on a separate Form 1099-B (or equivalent statement); there is an exception for futures, option and foreign currency contracts that may be reported on an aggregate basis.

If in the same transaction both covered and noncovered securities were sold, each type should be reported on a separate Form 1099-B (or equivalent statement). If some covered securities were held short term and others long term (over a year), the short-term transactions should be reported separately from the long-term transactions.

Can you report directly on Schedule D? You do not need to report certain transactions on Form 8949. You can aggregate the transactions reported on Forms 1099-B that show (in Box 3) that basis was reported to the IRS and report them directly on Schedule D if you do not have to adjust the basis, the amount of gain or loss, or the type of gain or loss (short-term or long-term). Check the Form 8949 instructions for other requirements. You may choose to report the transactions separately on Form 8949 even if direct reporting on Schedule D is allowed. If you qualify for direct reporting and choose to do so, the aggregated short-term transactions are entered on Line 1a of Schedule D and the aggregated long-term transactions are reported on Line 8a of Schedule D.

Reporting transactions first on Form 8949 and then entering totals on Schedule D. Use Part I of Form 8949 for short-term gains and losses (assets held one year or less) and Part II for long-term gains and losses (assets held more than one year). You may have to file more than one Part I or Part II, or multiple copies of both, depending on whether and how your transactions were reported on Form 1099-B (“Proceeds From Broker and Barter Exchange Transactions”). In Parts I and II of Form 8949, you must check a box to indicate whether your basis for sold securities was reported to the IRS by your broker on Form 1099-B. When reporting short-term transactions in Part I, check Box A if Form 1099-B shows that basis was reported to the IRS; check Box B if Form 1099-B shows that basis was not reported to the IRS; and check Box C if you did not receive Form 1099-B for the transactions. In Part II of Form 8949 for long-term transactions, you check Box D if Form 1099-B shows that basis was reported to the IRS, Box E if Form 1099-B shows that basis was not reported to the IRS; and Box F if you did not receive Form 1099-B for the transaction. If you need to check more than one type of box in either Part I or Part II, as when you have some Box A and some Box B or C transactions in Part I, or some Box D and some Box E or F transactions in Part II, you must complete a separate Part I or Part II for each type of box.

In the columns of Form 8949, you report transaction details. You report the sale proceeds in column (d) and your basis in column (e). Report your gain or loss in column (h).

If you did not receive a Form 1099-B (or substitute statement) for your transaction, enter in column (d) of Form 8949 the net proceeds. That is, reduce the gross proceeds by your selling expenses such as broker fees, commissions and state and local transfer taxes. Similarly, if you sold real estate and did not receive a Form 1099-S (or substitute statement), you should enter the net proceeds (gross proceeds minus your selling expenses) in column (d) of Form 8949.

If you received a Form 1099-B, the net proceeds should have been reported in Box 1d. If securities were sold because of the exercise of an option, the broker may either report the gross proceeds or reduce the proceeds by the option premiums; a box in Box 6 will be checked to indicate if the gross proceeds or net proceeds have been reported.

If a “covered” security was sold, the basis will be reported in Box 1e, and even if a “noncovered” security was sold (if so, Box 5 will be checked), basis may be shown in Box 1e.

On Form 8949, report the sales proceeds and basis as shown on Form 1099-B, and if you have to adjust the amounts shown, follow the Form 8949 instructions for entering the adjustment in column (g) and the adjustment code in column (f).

If you received a Form 1099-S for a real estate sale, you must enter your selling expenses as a negative adjustment in column (g) of Form 8949, with code “E” entered in column (f), to take into account your selling expenses not taken into account on the Form 1099-S.

Form 8949 must be attached to Schedule D. The totals from columns (d), (e), (g) and (h) of Form 8949 are transferred to the appropriate lines of Schedule D, depending on which Box was checked on Form 8949 (Box A, B, C, D, E, or F).

The Example below for John and Karen Taylor and accompanying worksheets illustrate how transactions are entered on Form 8949 and Schedule D.

5.9 Counting the Months in Your Holding Period

The period of time you own a capital asset before its sale or exchange determines whether capital gain or loss is short term or long term.

These are the rules for counting the holding period:

- A holding period is figured in months and fractions of months.

- The beginning date of a holding month is generally the day after the asset was acquired. The same numerical date of each following month starts a new holding month regardless of the number of days in the preceding month. If you acquire an asset on the last day of a month, a holding month ends on the last day of a following calendar month, regardless of the number of days in each month.

- The last day of the holding period is the day on which the asset is sold.

5.10 Holding Period for Securities

Rules for counting your holding period for various securities transactions are as follows:

Stock sold on a public exchange. The holding period starts on the day after your purchase order is executed (trade date). The day your sale order is executed (trade date) is the last day of the holding period, even if delivery and payment are not made until several days after the actual sale (settlement date).

Stock subscriptions. If you are bound by your subscription but the corporation is not, the holding period begins the day after the date on which the stock is issued. If both you and the company are bound, the date the subscription is accepted by the corporation is the date of acquisition, and your holding period begins the day after.

Tax-free stock rights. When you exercise rights to acquire corporate stock from the issuing corporation, your holding period for the stock begins on the day of exercise, not on the day after. You are deemed to exercise stock rights when you assent to the terms of the rights in the manner requested or authorized by the corporation. An option to acquire stock is not a stock right.

FIFO method for stock sold from different lots. If you purchased shares of the same stock on different dates and cannot determine which shares you are selling, the shares purchased at the earliest time are considered the stock sold first; this is called the FIFO (first-in, first-out) method (30.2).

Commodities. If you acquired a commodity futures contract, the holding period of a commodity accepted in satisfaction of the contract includes your holding period of the contract, unless you are a dealer in commodities.

Employee stock options. When an employee exercises a stock option, the holding period of the acquired stock begins on the day after the option is exercised. If an employee option plan allows the exercise of an option by giving notes, the terms of the plan should be reviewed to determine when ownership rights to the stock are transferred. The terms may affect the start of the holding period for the stock.

Wash sales. After a wash sale, the holding period of the new stock includes the holding period of the old stock for which a loss has been disallowed (30.6).

Other references. For the holding period of stock dividends, see 30.3; for short sales, see 30.5; and for convertible securities, see 30.7.

5.11 Holding Period for Real Estate

Your holding period starts on the day after the date of acquisition. The acquisition date is the earlier of: (1) the date title passes to you or (2) the date you take possession and you assume the burdens and privileges of ownership under the contract of sale; taking possession under an option agreement does not start your holding period. In disputes involving the starting and closing dates of a holding period, you may refer to the state law that applies to your sale or purchase agreement. State law determines when title to property passes.

If you convert a residence to rental property and later sell the home, the holding period includes the time you held the home for personal purposes.

Year-end sale. The date of sale is the last day of your holding period even if you do not receive the sale proceeds until the following year. For example, you sell land held for investment at a gain on December 29, 2017, receiving payment in January 2018. Your holding period ends on December 29, although the sale is reported in 2018 when the proceeds are received. Note that the December 29 gain transaction can be reported on your 2017 return by making an election to “elect out” of installment reporting (5.23). If you had a loss on the sale, it is reported as a loss for 2018, when the proceeds are received.

5.12 Holding Period: Gifts, Inheritances, and Other Property

Gift property. If, in figuring a gain or loss, your basis for the property under 5.17 is the same as the donor’s basis, you add the donor’s holding period to the period you held the property. If you sell the property at a loss using as your basis the fair market value at the date of the gift (5.17), your holding period begins on the day after the date of the gift.

Inherited property. The law gives an automatic holding period of more than one year for property inherited from someone who died before or after 2010. Report the transaction in Part II of Form 8949 (“Long-Term”) and enter “INHERITED” in column (b) as the date of acquisition. If property was inherited from someone who died in 2010 and the executor elected on Form 8939 to apply modified carryover basis rules (5.17), the holding period for property subject to those rules includes the period that the deceased held it; see Publication 4895 and Revenue Procedure 2011-41.

Where property is purchased by the executor or trustee and distributed to you, your holding period begins the day after the date on which the property was purchased.

Partnership property. When you receive property as a distribution in kind from your partnership, the period your partnership held the property is added to your holding period. But there is no adding on of holding periods if the partnership property distributed was inventory and was sold by you within five years of distribution.

Involuntary conversions. When you have an involuntary conversion and elect to defer tax on gain, the holding period for the qualified replacement property generally includes the period you held the converted property. A new holding period begins for new property if you do not make an election to defer tax.

5.13 Calculating Gain or Loss

In most cases, you know if you have realized an economic profit or loss on the sale or exchange of property. You know your cost and selling price. The difference between the two is your profit or loss. The computation of gain or loss for tax purposes is similarly figured, except that the basis adjustment rules may require you to increase or decrease your cost and the amount-realized rules may require you to increase the selling price. As a result, your gain or loss for tax purposes may differ from your initial calculation.

When reporting a sale on Form 8949, follow the form instructions for reporting sale proceeds, basis, and selling expenses (5.8).

Table 5-2 Figuring Gain or Loss on Form 8949 and Schedule D

| 1. | Amount realized or total selling price (5.14), minus selling expenses*. |

$ ___________ | |

| 2. | Cost or other unadjusted basis (5.16). | $ ___________ | |

| 3. | Plus: Improvements; certain legal fees (5.20). | $ ___________ | |

| 4. | Minus: Depreciation, casualty losses (5.20). | $ ___________ | |

| 5. | Adjusted basis: 2 plus 3 minus 4 (5.20). | $ ___________ | |

| 6. | Gain or loss: Subtract 5 from 1. | $ ___________ |

*Selling expenses on Form 8949 and Schedule D. As discussed in 5.8, the Form 8949 instructions require you to report the net proceeds (gross proceeds minus your selling expenses) if you did not receive a Form 1099-B or Form 1099-S for your transaction. If you received a Form 1099-B or 1099-S on which the net proceeds shown does not include all of your selling expenses, you enter on Form 8949/Schedule D the proceeds shown on Form 1099-B and then enter the additional selling expenses as a negative adjustment.

5.14 Amount Realized Is the Total Selling Price

Amount realized is the tax term for the total selling price. It includes cash, the fair market value of additional property received, and any of your liabilities that the buyer agrees to pay. The buyer’s note is included in the selling price at fair market value. This is generally the discounted amount that a bank or other party will pay for the note.

Sale of mortgaged property. The selling price includes the amount of the unpaid mortgage. This is true whether or not you are personally liable on the debt, and whether or not the buyer assumes the mortgage or merely takes the property subject to the mortgage. The full amount of the unpaid mortgage is included, even where the value of the property is less than the unpaid mortgage. Computing amount realized on foreclosure sales is discussed in Chapter 31 (31.9).

If, at the time of the sale, the buyer pays off the existing mortgage or your other liabilities, you include the payment as part of the sales proceeds.

5.15 Finding Your Cost

In figuring gain or loss, you need to know the “unadjusted basis” of the property sold. This term refers to the original cost of your property if you purchased it. The general rules for determining your unadjusted basis are in 5.16. Basis for property received by gift or inheritance is in 5.17; rules for surviving joint tenants are in 5.18. Keep in mind that you have to adjust this figure for improvements to the property, depreciation, or losses (5.20).

5.16 Unadjusted Basis of Your Property

To determine your tax cost for property, first find in the following section the unadjusted basis of the property, and then increase or decrease that basis (5.20).

Property you bought. Unadjusted basis is your cash cost plus the value of any property you gave to the seller. If you assumed a mortgage or bought property subject to a mortgage, the amount of the mortgage is part of your unadjusted basis.

Purchase expenses are included in your cost, such as commissions, title insurance, recording fees, survey costs, and transfer taxes.

If you buy real estate and reimburse the seller for property taxes he or she paid that cover the period after you took title, and you include the payment in your itemized deduction for real estate taxes (16.4), do not add the reimbursement to your basis. However, if you did not reimburse the seller, you must reduce your basis by the seller’s payment.

If at the closing you also paid property taxes attributable to the time the seller held the property, you add such taxes to basis.

Property obtained for services. If you paid for the property by providing services, the value of the property, which is taxable compensation, is also your adjusted basis.

Property received in taxable exchange. Your unadjusted basis for the new property is generally equal to the fair market value of the property received. See below for tax-free exchanges.

Property received in a tax-free exchange. The computation of basis is made on Form 8824. If the exchange is completely tax free (6.1), your basis for the new property will be your basis for the property you gave up in the exchange, plus any additional cash and exchange expenses you paid. If the exchange is partly nontaxable and partly taxable because you received “boot” (6.3), your basis for the new property will be your basis for the property given up in the exchange, decreased by any cash received and by any liabilities on the property you gave up, and increased by any cash and exchange expenses you paid, liabilities on the property you received, and gain taxed to you on the exchange. Gain is taxed to the extent you receive “boot,” in the form of cash or a transfer of liabilities that exceeds the liabilities assumed in the exchange; see 6.3 for a discussion on taxable boot. The Example in 6.3 illustrates the basis computation.

Property received from a spouse or former spouse. Tax-free exchange rules apply to transfers of property to a spouse, or to a former spouse where the transfer is incident to a divorce (6.7). The spouse receiving the property takes a basis equal to that of the transferor. Certain adjustments may be required where a transfer of mortgaged property is made in trust. The tax-free exchange rule applies to transfers between spouses after July 18, 1984.

If you received property before July 19, 1984, under a prenuptial agreement in exchange for your release of your dower and marital rights, your basis is the fair market value at the time you received it.

New residence purchased under tax deferral rule of prior law. If you sold your old principal residence and bought a qualifying replacement under the prior law deferral rules, your basis for the new house is what you paid for it, less any gain that was not taxed on the sale of the old residence.

Property received as a trust beneficiary. Generally, you take the same basis the trust had for the property. But if the distribution is made to settle a claim you had against the trust, your basis for the property is the amount of the settled claim.

If you received a distribution in kind for your share of trust income after June 1, 1984, your basis is the basis of the property in the hands of the trust. If the trust elects to treat the distribution as a taxable sale, your basis is generally fair market value. For distributions before June 2, 1984, the basis of the distribution is generally the value of the property to the extent allocated to distributable net income.

Property acquired with involuntary conversion proceeds. If you acquire replacement property (18.23) with insurance proceeds from destroyed property, or a government payment for condemned property, basis is the cost of the new property decreased by the amount of the gain that is deferred (18.24). If the replacement property consists of more than one piece of property, basis is allocated to each piece in proportion to its respective cost.

5.17 Basis of Property You Inherited or Received as a Gift

Special basis rules apply to property you received as a gift or that you inherited. Gifts from a spouse are subject to the rules discussed in 6.7. If you are a surviving joint tenant who received full title to property upon the death of the other joint tenant, see 5.18.

Basis of Property Received as Gift

If the fair market value of the property equaled or exceeded the donor’s adjusted basis (5.20) at the time you received the gift, your basis for figuring gain or loss when you sell it is the donor’s adjusted basis plus all or part of any gift tax paid; see the gift tax rule below. Additional adjustments to basis (plus or minus) may be required for the period you held the property (5.20).

If on the date of the gift the fair market value of the property was less than the donor’s adjusted basis, there are two basis rules, one for determining if you have a gain, and another for determining if you have a loss. For purposes of figuring gain when you sell the property, your basis is the donor’s adjusted basis, and your basis for figuring loss is the fair market value on the date of the gift. Additional adjustments to basis (plus or minus) may be required for the period you held the property (5.20).

Depending on your selling price, it is possible that you will have neither gain nor loss when you sell. This happens when you figure a loss when using the donor’s basis as your basis (the basis rule for determining if you have a gain), and you figure a gain when using the fair market value of the property at the time of the gift as your basis (the basis rule for determining if you have a loss); see Line 3 of Example 1 below.

Did the donor pay gift tax? If the donor paid a gift tax (39.2) on the gift to you, your basis for the property is increased under these rules:

- For property received after December 31, 1976, the basis is increased by an amount that bears the same ratio to the amount of gift tax paid by the donor as the net appreciation in the value of the gift bears to the amount of the gift after taking into account the annual gift tax exclusion (39.2) that applied in the year of the gift. The increase may not exceed the tax paid. Net appreciation in the value of any gift is the amount by which the fair market value of the gift exceeds the donor’s adjusted basis immediately before the gift. See Example 3 below.

- For property received after September 1, 1958, but before 1977, basis is increased by the gift tax paid on the property but not above the fair market value of the property at the time of the gift.

Depreciation on property received as a gift. If the property is depreciable (Chapter 42), your basis for computing depreciation deductions is the donor’s adjusted basis (5.20), plus all or part of the gift tax paid by the donors as previously discussed.

To figure gain or loss when you sell the property, you must adjust basis for depreciation you claimed and make other adjustments required for the period you hold the property (5.20). If accelerated depreciation is claimed and you sell at a gain, you are subject to the ordinary income recapture rules (44.1).

Basis of Inherited Property

Your basis for property inherited from someone who died before or after 2010 is generally the fair market value of the property on the date of the decedent’s death. If the executor of the decedent’s estate elected to use an alternate valuation date (within six months after the date of death), your basis is the fair market value on the alternate valuation date. If the decedent died in 2010, your basis may be the fair market value, but see below for the exception where the executor filed Form 8939.

If the property increased in value while the decedent owned the property, the “step-up” in basis to its fair market value can provide a substantial tax break. If your basis is the value at the decedent’s death or at the alternate valuation date, then, when you sell the property, you completely avoid income tax on the appreciation in value that occurred while the decedent owned it.

If you inherit property that was reported on an estate tax return (Form 706) filed after July 31, 2015, the executor is generally required to report the value of the estate assets to the IRS on Form 8971 and Schedule A, and if the property you inherit increased estate tax liability, you will face a penalty if you claim a basis for the property that exceeds the value shown on your copy of Schedule A. See below for details of this basis consistency rule.

If you owned the property jointly with the deceased, see 5.18.

If you inherit appreciated property that you (or your spouse) gave to the deceased person within one year of his or her death, your basis is the decedent’s basis immediately before death, not its fair market value.

If the inherited property is subject to a mortgage, your basis is the value of the property, and not its equity at the date of death. If the property is subject to a lease under which no income is to be received for years, the basis is the value of the property—not the equity.

You might be given the right to buy the deceased person’s property under his or her will. This is not the same as inheriting that property. Your basis is what you pay—not what the property is worth on the date of the deceased’s death.

If property was inherited from an individual who died after 1976 and before November 7, 1978, and the executor elected to apply a carryover basis to all estate property, your basis is figured with reference to the decedent’s basis. The executor must inform you of the basis of such property.

Community property. Upon the death of a spouse in a community property state, one-half of the fair market value of the community property is generally included in the deceased spouse’s estate for estate tax purposes. The surviving spouse’s basis for his or her half of the property is 50% of the total fair market value. For the other half, the surviving spouse, if he/she receives the asset, or the other heirs of the deceased spouse have a basis equal to 50% of the fair market value.

Did executor of decedent who died in 2010 elect modified carryover basis rules on Form 8939? If you inherited property from a person who died in 2010, you get a full stepped-up basis (to fair market value on date of death or alternate valuation date), provided the executor did not elect to file Form 8939. Under the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010, the executors of estates of individuals dying in 2010 were allowed to opt out of estate tax entirely (no estate tax at all applied even if the gross estate exceeded the $5 million exemption) provided an election was made on Form 8939 to apply modified carryover basis rules under which the heirs generally received a stepped-up basis only for the first $1.3 million in assets, plus an additional $3 million for property passing to a surviving spouse. Executors had to make the modified carryover basis election on Form 8939 by January 17, 2012. Further details on the modified carryover basis rules are in Publication 4895 and Revenue Procedure 2011-41.

If the executor of a 2010 estate did not elect on Form 8939 to apply the modified carryover basis rules, the regular stepped-up basis rules apply.

Farm or closely-held business property. If for estate tax purposes the executor of the estate valued qualifying real estate based on its use as a farm or use in a closely-held business, rather than at its fair market value, that farm or business value is the basis for the heirs. If you inherit such property, contact the executor for the special valuation.

Basis consistency requirement may apply to you if you inherit property reported on estate tax return filed after July 31, 2015. Legislation was enacted in 2015 in an attempt to ensure that the values reported for property on a federal estate tax return (Form 706) are used by the estate beneficiaries as their basis for the assets they inherit. Congress was concerned that some beneficiaries understate their gain when they sell inherited property, or overstate a loss (for investment property), by claiming a basis for the property that is more than the fair market value reported by the executor on the estate tax return. Similarly, deductions for depreciation or amortization could be inflated by using a basis higher than the estate tax value of the property.

Reporting by executor to the IRS and beneficiaries on Form 8971 and Schedule A. An executor who files an estate tax return generally must report the value of the property included in the gross estate to the IRS on Form 8971 and Schedule A no later than 30 days after the date the estate tax return is filed, or if earlier, 30 days after the filing due date with extensions. Executors are subject to penalties for failure to file timely and correct Forms 8971 and Schedules A. The penalty amounts generally depend on how late the filing is; details are in the Form 8971/Schedule A instructions.

However, the Form 8971 and Schedule A requirements do not apply if the gross estate (plus adjusted gifts) was under the filing threshold for Form 706 and the sole reason for filing the estate tax return was to make a portability election that allows the decedent’s unused estate tax exemption to be preserved for the decedent’s surviving spouse (39.9). Also, the reporting requirements do not apply if the estate tax return is filed solely to make a generation-skipping transfer election.

Certain proprty included in the gross estate is exempt from reporting. This includes (1) cash bequests, but not coins or bills with numismatic value, (2) income in respect of a decedent (11.16), (3) small items of tangible personal property (generally household and personal effects) that do not require an estate tax appraisal, and (4) property sold by the estate and therefore not distributed to a beneficiary.

Where reporting is required, the executor must submit to the IRS a separate Schedule A for each beneficiary receiving property from the estate, and give each beneficiary (within the above 30-day deadline) a copy of his/her Schedule A. Schedule A provides information about the beneficiary and the property he or she has inherited (e.g., the beneficiary’s name and tax identification number, description of the property, and its valuation). If the executor has not yet determined which beneficiary will receive an item of property as of the due date of the Form 8971 and Schedule(s) A, that property must be reported on a Schedule A for each beneficiary who might receive it. In this case, the same property will be reported on multiple Schedules A, and when the property is actually distributed, or the property is used to fund the distributions of multiple beneficiaries, the executor may file a supplemental Form 8971 and corresponding Schedules A to each of the affected beneficiaries.

Potential penalty for beneficiary. You will receive a copy of your Schedule A from the executor, but not a copy of the Form 8971 and Schedules A prepared for other beneficiaries. Column C of Schedule A will indicate if the property you inherited increased the estate tax liability payable by the estate. If it did (“Y” will be entered in this column), there is a notice on your Schedule A warning you that you are subject to the basis consistency requirement. This means that you are required to use as your basis the estate tax value for that property, which is shown in Column E of the Schedule A. If you claim a basis that exceeds the estate tax value when reporting a sale or other taxable event (such as depreciation), you are subject to a 20% “accuracy-related” penalty (48.6). If the value reported to you in Column E subsequently changes (such as when a valuation dispute is settled), the executor must send you (and the IRS) an updated Schedule A within 30 days after the adjustment.

If you are a surviving spouse and received property that qualified for the marital deduction, that property did not increase the estate tax liability (“N” should be entered in Column C) and the basis consistency rule and potential penalty do not apply.

5.18 Joint Tenancy Basis Rules for Surviving Tenants

If you are a surviving joint tenant, your basis for the property depends on how much of the value was includible in the deceased tenant’s gross estate, and this depends on whether the joint tenant was your spouse or someone other than your spouse.

Caution: If you inherited property from a person who died in 2010 and the executor elected on Form 8939 to apply the modified carryover basis rules (5.17), basis will be determined under that election.

Qualified joint interest rule for survivor of spouse who died after 1981. A “qualified joint interest” rule applies to a joint tenancy with right of survivorship where the spouses are the only joint tenants, and to a tenancy by the entirety between a husband and wife. Where the surviving spouse is a U.S. citizen, one-half of the fair market value of the property is includible in the decedent’s gross estate. This is true regardless of how much each spouse contributed to the purchase price. Fair market value is fixed at the date of death, or six months later if an estate tax return is filed and the optional alternate valuation date is elected.

The qualified joint interest rules do not apply if the surviving spouse is not a U.S. citizen on the due date of the estate tax return. In this case, the basis rule is generally the same as the rule discussed below for unmarried joint tenants.

Surviving spouse’s basis. Under the qualified joint interest rules, the surviving spouse’s basis equals 50% of the date-of-death fair market value (the amount included in the decedent’s gross estate), plus one-half of the original cost basis for the property; see Example 1 below. Similarly, if no estate tax return was due because the value of the estate was below the filing threshold, the surviving spouse’s basis is one-half of the fair market value of the property at the date of death (alternate valuation is not available) plus one-half of the original cost basis. If depreciation deductions for the property were claimed before the date of death, the surviving spouse must reduce basis by his or her share (under local law) of the depreciation; see Example 2 below.

Unmarried joint tenants. If you are a surviving joint tenant who owned property with someone other than your spouse, your basis for the entire property is your basis for your share before the joint owner died plus the fair market value of the decedent’s share at death (or on the alternate valuation date if the estate uses the alternate date). Even if the estate is too small to require the filing of an estate tax return, you may still include the decedent’s share of the date-of-death value in your basis. However, if no estate tax return is required, you may not use the alternate valuation date basis.

Exception for pre-1954 deaths. Where property was held in joint tenancy and one of the tenants died before January 1, 1954, no part of the interest of the surviving tenant is treated, for purposes of determining the basis of the property, as property transmitted at death. The survivor’s basis is the original cost of the property.

Survivor of spouse who died before 1982. The basis rule for a surviving spouse who held property jointly (or as tenancy by the entirety) with a spouse who died before 1982 is generally the same as the above rule for unmarried joint tenants. However, special rules applied to qualified joint interests and eligible joint interests are discussed below.

Qualified joint interest and eligible joint interest where spouse died before 1982. Where, after 1976, a spouse dying before 1982 elected to treat realty as a “qualified joint interest” subject to gift tax, such joint property was treated as owned 50–50 by each spouse, and 50% of the value was included in the decedent’s estate. Thus, for income tax purposes, the survivor’s basis for the inherited 50% half of the property is the estate tax value; the basis for the other half is determined under the gift rules (5.17). Personal property is treated as a “qualified joint interest” only if it was created or deemed to have been created after 1976 by a husband and wife and was subject to gift tax.

Where death occurred before 1982 and a surviving spouse materially participated in the operation of a farm or other business, the estate could have elected to treat the farm or business property as an “eligible joint interest,” which means that part of the investment in the property was attributed to the surviving spouse’s services and that part was not included in the deceased spouse’s estate. Where such an election was made, the survivor’s basis for income tax purposes includes the estate tax value of property included in the decedent’s estate.

5.19 Allocating Cost Among Several Assets

Allocation of basis is generally required in these cases: when the property includes land and building; the land is to be divided into lots; securities or mutual fund shares are purchased at different times; stock splits; and in the purchase of a business.

Purchase of land and building. To figure depreciation on the building, part of the purchase price must be allocated to the building. The allocation is made according to the fair market values of the building and land. The amount allocated to land is not depreciated.

Purchase of land to be divided into lots. The purchase price of the tract is allocated to each lot, so that the gain or loss from the sale of each lot may be reported in the year of its sale. Allocation is not made ratably, that is, with an equal share to each lot or parcel. It is based on the relative value of each piece of property. Comparable sales, competent appraisals, or assessed values may be used as guides.

Securities. See 30.2 for details on methods of identifying securities bought at different dates. See 30.3 for allocating basis of stock dividends and stock splits and 30.4 for allocating the basis of stock rights.

Mutual fund shares. See 32.10 for determining the basis of mutual fund shares where purchases were made at different times.

Purchase price of a business. See 44.9 for allocation rule.

5.20 How To Find Adjusted Basis

After determining the unadjusted cost basis for property (5.16 – 5.19), you may have to increase it or decrease it to find your adjusted basis, which is the amount used to figure your gain or loss on a sale (5.13).

- Additions to basis. You add to unadjusted basis the cost of these items:

- All permanent improvements and additions to the property and other capital costs. Increase basis for capital improvements such as adding a room or a fence, putting in new plumbing or wiring, and paving a driveway. Also include capital costs such as the cost of extending utility service lines, assessments for local improvements such as streets, sidewalks, or water connections, and repairing your property after a casualty (for example, repair costs after a fire or storm).

- Legal fees. Increase basis by legal fees incurred for defending or perfecting title, or for obtaining a reduction of an assessment levied against property to pay for local benefits.

- Sale of unharvested land. If you sell land with unharvested crops, add the cost of producing the crops to the basis of the property sold.

- Decreases to basis. You reduce cost basis for these items: