Eight Greatest Ideas for Leading Innovation

Idea 93: Successful innovation

Changing things is central to leadership. Changing them before anyone else is creative leadership.

Ordway Tead, US author and educator

Innovation should not be a reactive process but part of a long-term strategy that gives direction. It needs to be fed by the dynamo of a corporate sense of purpose.

Such a strategy will balance the present needs of producing and marketing existing goods and services – the commercial priority –with the middle- and long-term requirement of research and development.

A balanced and coherent strategy will enable your organization to build on its past successes and create its desired future. It is the only sure pathway to profitable growth.

There are always reasons for not becoming an innovative organization, not least the fact that it costs money to go down that path. But can you afford the cost of the alternative?

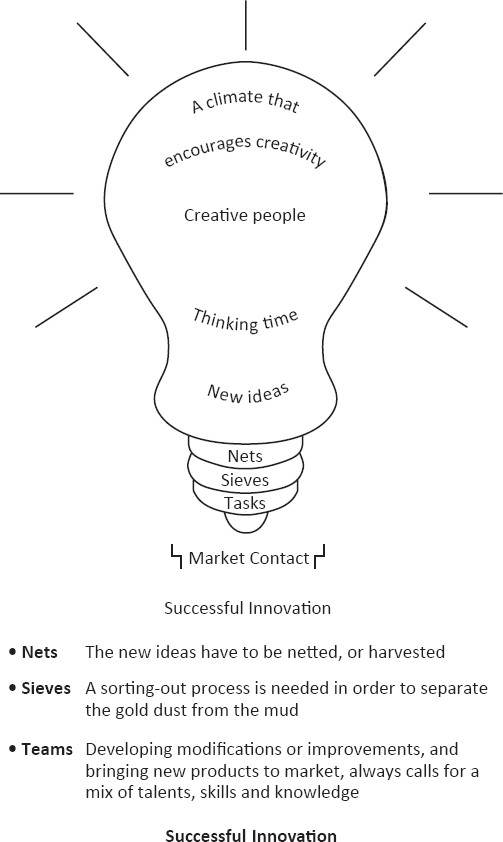

This model suggests that good new ideas are more likely to be forth-coming in an organization that encourages creative people and allows time for productive thinking. Needless to say, this requires leadership and vision to bring about and sustain the right climate.

The results of successful innovation include:

- stimulated team members

- delighted customers

- profitable growth

He who dares nothing need hope for nothing.

English proverb

Checklist for the innovative organization

Checklist for the innovative organization

- Is the top management team committed to innovation?

- Are mistakes and failures accepted as part of risk taking?

- Do creative people join and stay with the organization?

- Is innovation rewarded (financially or by promotion or both)?

- Can ideas be exchanged informally and are opportunities provided to do this?

- Are resources given for new ideas?

- Do all staff see themselves as part of the creative and innovative processes?

- Is it fun to work in your organization?

Idea 94: Team creativity in action

Many ideas grow better when transplanted into another mind than in the one where they sprang up.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, American jurist

The invention of Scotch Tape is a highlight in the story of 3M, the Minnesota corporation that grew from being a maker of mediocre sandpaper into an international conglomerate:

The salesmen who visited the auto plants noticed that workers painting new two-toned cars were having trouble keeping the colours from running together.

Richard G Drew, a young 3M lab technician, came up with the answer: masking tape, the company's first tape. Drew then figured out how to put adhesive on it and Scotch Tape was born, initially for industrial packaging.

It didn't really begin to roll until another imaginative 3M hero, sales manager John Borden, created a dispenser with a built-in blade.

You can see that members of this company had learnt to build on one another's ideas. The process of innovation is largely incremental. It requires the efforts and contributions of a team if an idea is to be brought successfully to the marketplace.

Building on ideas

At the core of team creativity is the capacity to build on or improve other people's ideas, and to subject your own ideas to the same process. ‘The typical eye sees the 10 per cent bad of an idea,’ writes Charles F Kettering, ‘and overlooks the 90 per cent good’.

Every fool can see what is wrong. See what is good in it!

Winston Churchill, speaking to his cabinet colleagues

| Questions/statements | Notes |

| Bringing in | |

‘Bob, you have had experience in several other industries, how did they tackle this problem?’ |

Meets individual needs as well as the task. |

| Stimulating | |

‘Imagine we were starting from scratch again. How would we do it?’ |

Brains are like car engines. They need warming up by outrageous ideas or thought-provoking suggestions. |

| Building on | |

‘Can't we develop the idea behind Mary's suggestion of cuting down the number of files? Could we use the computer more? How else can we improve our information storage system?’ |

Entails seeing the positive idea or principle in a suggestion and taking it further. |

| Spreading | |

‘We can also include Jim's suggestion about time keeping and Mary's point about safety in the plan.’ |

Helps to develop a team solution, a creative process of weaving separate threads and loose ends together into a whole. |

| Accepting while rejecting | |

‘Mike's proposal is an interesting and helpful one, but it would take us rather too long so we must leave it on one side for the present.’ |

You are accepting Mike, but rejecting his plan in a gracious way. He will not be resentful, and may come up with the winning idea next time. |

How to criticize other people's new ideas

‘A new idea is delicate,’ said US entrepreneur Charles Brewer. ‘it can be killed by a sneer or a yawn; it can be stabbed to death by a quip and worried to death by a frown on the right man's brow.’

The management of criticism is almost as important as the management of innovation. Make no mistake, criticism has to be done. Expensive mistakes may occur, leading organizations up blind and profitless alleyways, if ideas are not evaluated rigorously at the right time.

Henry Ford used to content himself with just three questions:

- Is it needed?

- Is it practical?

- Is it commercial?

These three key questions and their satellites do have to be pressed home hard in commercial and industrial organizations in the right way, at the right time and in the right place. Don't confuse the art of the possible with the art of the profitable; at the same time, they should not be applied prematurely in the creative process.

Sometimes, however, ideas have to evolve quite far before any practical and commercial use becomes apparent. But tested they must be by others at various stages of their life history. The good ones are those that can jump the hurdles of criticism.

Testing or criticizing other people's new ideas – and being on the receiving end of that treatment – is often not a pleasant process. It can be downright demoralizing to the receiver. We have to learn ‘the manners of conversation’. In our context of criticism, that means learning to express our views with tact and diplomacy.

Idea 95: Harvesting ideas

The creative act thrives in an environment of mutual stimulation, feedback and constructive criticism – in a community of creativity.

William T Brady

Each person who works with you has about 10,000 million brain cells. Each of those cells can link up with about 10,000 of its neighbours, giving some 10 billion possible combinations. Each person has more brain cells than there are people on the face of the earth.

Your challenge as a leader is to elicit the new ideas and fresh thinking that are potentially there in those who work for you. In the coldest flint there is a hot fire, says an English proverb.

One way of doing so is to introduce what could be called innovative systems, notably suggestion schemes and quality circles, which are designed to encourage and harvest ideas at work.

Managers who are not leaders tend to believe that all problems can be solved by introducing a system. But systems are usually only half of the solution. The other half is the people running them and the people participating in them. That spells out the need for leadership at all levels, together with a sound recruitment policy coupled with a comprehensive training programme. There is no such thing as instant innovation.

In modern times the first managers who demonstrated real faith in the creativity within their people, and systematically went about harvesting ideas from the workforce, were the Japanese.

Of course, this wasn't an entirely new idea. Henry Ford introduced the world's first assembly line for car manufacture in 1913. Every man on the payroll was invited to contribute ideas, and the good ones were implemented without delay. Ford and his managers created an atmosphere in which improvement was the real product.

Suggestion schemes

In 1857 the Chance Brothers of Smethwick, surprised when their workers suggested ways of improving production and saving on materials, hit on the idea of putting a wooden box where such ideas could be posted. The scheme proved to be of immense worth to the firm and to the workers. It was the world's first suggestion scheme.

What is honoured in a country will be cultivated there.

Plato

Exercise

A staff member working in the transport industry got himself into the Guinness Book of Records with the number of suggestions he offered during a career of over 40 years. Tick the number of ideas he came up with:

The enthusiastic support of leaders at all levels is essential. Lazy managers who merely put up a box for suggestions in the workplace and sit back to await a few million-dollar ideas are wasting their opportunity. Ask some pointed questions. Give people a fairly specific direction for their thinking. Our imaginations must have bones to gnaw on.

Quality circles

A quality circle is a group of 4 to 12 people coming from the same work area, performing similar jobs, who voluntarily meet on a regular basis to identify, investigate, analyze and solve their own work-related problems. The circle presents solutions to management and is usually involved in implementing and later monitoring these. Notice that unlike suggestion schemes, quality circles employ the principle of team creativity.

Quality circles were developed after the Second World War in Japan. It is traditionally important there to ‘gather the wisdom of the people’. Japanese industry, once so notorious for shoddy workmanship and low-quality merchandise, was transformed by accepting the gospel of quality. At one time it was estimated that 11 million Japanese were organized into quality circles, and children were taught in school the problem-solving techniques they use.

The achievement of excellence can only occur if the organization promotes a culture of creative dissatisfaction.

Unattributed

By the way, the staff member in the transport company contributed more than 20,000 ideas.

Idea 96: Ploughing the ground

There is a natural opposition among men to anything they have not thought of themselves.

Sir Barnes Wallis, English engineer and inventor

No farmer sows seeds into hard, frozen or unyielding ground. You have to prepare the way for change. Unless you can create some creative dissatisfaction with things as they are, you cannot foster a willingness to change. Complacency is a greater enemy to change than fear. Indeed complacency, arrogance and complexity are the three mortal diseases that bring great institutions down into the dust.

Like the prophets of old, go out into the highways and byways of your organization and cry out in a loud voice:

- A thing is not right because we do it.

- A method is not good because we use it.

- Equipment is not the best because we own it.

Your first target must be the assumptions and fixed ideas of the organization: the luggage it brings from its successful past. It is today's success that often breeds tomorrow's failure.

‘It is not only what we have inherited from our fathers that exists again in us’, wrote dramatist Henrik Ibsen, ‘but all sorts of old dead ideas and all kinds of old dead beliefs... They are not actually alive in us; but they are dormant, all the same, and we can never be rid of them.’ Watch out for these skeletons in the cupboard.

Notice that innovation often comes when a fresh mind, untrammelled by these dead ideas and assumptions, enters a traditional industry. Sir Henry Bessemer, the British civil engineer who invented the Bessemer process for converting molten pig-iron into steel, once said: ‘I had an immense advantage over many others dealing with the problem in as much as I had no fixed ideas derived from long-established practice to control and bias my mind, and did not suffer from the general belief that whatever is, is right.’ But in his case, as with many ‘outsiders’, ignorance and freedom from established patterns of thought in one field were joined with knowledge and training in other fields.

How do you plough up the ground? Ask plenty of questions, such as:

- Why are we doing it this way rather than any other?

- What are the criteria for success?

- What is the evidence that we are being successful?

- When did we last review these procedures?

- Who among our competitors is doing things differently and with what results?

- Where is the key research and development being done in this area?

‘When a road is once built,’ wrote Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘ It is a strange thing how it collects traffic, how every year as it goes on, more and more people are found to walk thereon, and others are raised up to repair and perpetuate it, and keep it alive.’

The kinds of questions listed above, repeated often, are like the points of a pneumatic drill digging up the hardened roads of organizational procedures. You cannot sow the seeds of desirable change on tarmac roads.

Idea 97: Market your ideas

The burden of proof is on you and your colleagues to persuade others in the organization, not least the top management, that the change you propose is a good one, namely a significant and cost-effective improvement on present practice.

As money is the language of business, you have to be able to show that, at least in the medium term, the new idea or innovation will cut costs, add to profits or serve some other legitimate corporate interest. You sell ideas best by pointing out the benefits it will confer on the ‘buyer’, be he or she an external customer or an internal member of the same organization as yourself.

In the legal sphere it is a principle that no one should be allowed to act as judge in their own case. The same principle applies in innovation. Your own ideas do need to be subjected to critical evaluation by others.

‘New ideas can be good or bad, just the same as old ones,’ remarked Franklin D Roosevelt. Organizations, like society at large, have to protect themselves against needless innovation, including perhaps some of your less than brilliant brainwaves. The ‘newer-is-truer’ assumption is so often found to be a false one.

In a truly innovative organization, with developed team creativity at all levels, your critics will fortunately have open and positive minds. They will perceive the positive element in what you are proposing. They will test your ideas and, if necessary, reject them with tact. Or they may accept them and build on them, so that the process of innovation gets underway. You can help them to see the value of a proposed change if you present it to individuals and groups with skill.

Some creative thinkers are quite adept at finding their way through the political undergrowth of the organization. Others are not so good at presenting their ideas, getting them accepted and securing the necessary resources. That is where introducing the system of project sponsors can be such a help. Someone high in the organization is appointed to help the innovator gain access to resources and to protect the project when it falters.

Acting as a sponsor for an untried project is no picnic. Most sponsors, I believe, tend to bet on people rather than on products. As the proverb says, captains bite their tongues until they bleed. This means that they have to keep their hands off the project. The first virtue of a sponsor is faith. The second is patience. And the third is understanding the differences between temporary setbacks and terminal problems.

It is at this level – the level of the sponsor – that there is a real opportunity to grow the seeds of innovation. Make sponsoring an explicit part of the job description of every top manager. When managers come in for appraisals, they should be asked about the new projects under their wings. The economics of projects is not the first issue to raise. Always consider first the vision of the payoff.

In organizations that rate low in creativity and innovation, the process is considerably less effective and much more painful for all concerned if they do not appoint sponsors to act as godparents to new ideas.

William James summed up a familiar pattern:

First a new theory is attacked as absurd; then it is admitted to be true but obvious and insignificant; finally it is seen to be so important that its adversaries claim that they themselves discovered it.

In what ways can I improve my ability to market new ideas, both within the organization I work for and to potential customers?

In what ways can I improve my ability to market new ideas, both within the organization I work for and to potential customers?

Idea 98: Have a practice run

What is conservatism? Is it not adherence to the old and tried against the new and untried?

Abraham Lincoln, 16th US President

Men and women tend not to believe in new things until they have experience of them. Therefore why not suggest an experiment? If something is tried and tested, so that it can be matched against the present state, then it is much more likely to be accepted.

Remember that experimenting involves only a limited commitment. People are usually much more comfortable with that. An experiment is only worth conducting, however, if there will be a fair and comprehensive review of the results. That does not preclude hard debate, for results are often open to several interpretations and it is important to arrive at the truth of the matter.

In the politics of innovation the proposal for a trial run – in, for example, one sector of the organization – is often an acceptable compromise as far as ‘conservatives’ are concerned. Its drawback is the extra time it adds on to the bill. Indeed, it can be used merely as a delaying tactic by those who have no intention or willingness to change.

Nevertheless, it is always wise to assume the best motives in your adversaries and attribute to them the same rationality that you believe you possess yourself. In this way, they will surprise you by their willingness to change.

‘Progress is the mother of problems,’ wrote G K Chesterton. You only have to contemplate the problems posed to us by the advance of science to see the truth of his statement. If any change is made there will be both manifest and latent consequences. The manifest consequences are the ones that can be foreseen; the latent ones only emerge during or after the innovation has been made.

Sometimes hindsight shows that the innovation has not yielded the promised benefits. Perhaps the original produce or service had some quality that has been lost in the improvement? In that case, if it is not too late, why not revert to the original?

Hence the wisdom, if time permits, of conducting trials or experiments before adopting any innovation wholesale. Who would like to fly in a new aircraft that had not undergone rigorous test flights?

Time spent on reconnaissance is seldom wasted.

Idea 99: Make change incremental

Organizational inertia is not entirely detrimental. Sometimes it protects individuals and groups within the organization from constant knee-jerk reactions to fluctuations in conditions, often engineered by mindless, mercenary managers who are here today and gone tomorrow.

Only when change – social, economic and technological – is rapid in the environment does torpid inertia become a real liability. For rapid change calls for a rapid response.

Organizations that put their head in the sand and ignore change may find that they have to make sudden and relatively great changes in order to catch up and survive. This form of crisis management should be avoided. It arouses too much anxiety and fear about the personal consequences of change.

Gradual or incremental change is much better. As we have seen, innovation should always be evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Wearing these clothes, it is much less threatening.

Therefore innovation should be planned in gradual stages, part of a continuous process of adaptation to changing circumstances. It should not be a panic response to change that is now taking an organization by the throat because yesterday that same organization failed to take it by the hand.

Use the time available to communicate carefully about the need for change, experiment and review. ‘Desire to have things done quickly prevents their being done thoroughly,’ reflected Confucius. With innovation it is usually best to make haste slowly.

An inch is a cinch, a yard is hard.

Idea 100: Communicate to innovate

Good communication supplies a vital dimension in the climate that fosters innovation. You as an individual manager have your share in the responsibility for ensuring that it happens. That means that you should:

- Seize opportunities to talk to your people about the importance of new ideas for improving the product range and reducing costs. Give examples and tell stories of changes that have been successfully implemented.

- Explain why suggested ideas have been accepted or rejected for further investigation and development. What are the selection criteria for ideas? Give your team regular progress updates on the passage through the organization of ideas that originated within its discussions.

- Give recognition and reward appropriately – the most powerful communication of all – the ideas that really do make a difference for the better to your business.

Remember that progress motivates. If you never give people feedback they will soon lose interest. Remember, too, that innovative change may be exciting to you, a vista of new opportunity, but to others in your organization it may appear to be a threat. Does it, for example, involve job losses? Or a reduction in take-home pay? Or more unsocial hours of work?

Make sure that you bear the circle of individual needs in mind when you communicate about necessary and desirable corporate change. If you can demonstrate that the innovation, be it large or small, benefits the individuals who will have to implement it as well as the common good, your task of improvement becomes a lot easier. So be truthful – and be prepared to spend a lot of time talking!

The willing bird flies farther than the thrown stone.

Follow-up test

- Successful innovation requires real commitment from the top. Are you giving that positive lead?

- Reviewing its track record for innovation in the last two years, would you say that your organization was ahead of all its competitors? If not, why not?

- Have you built a climate of team creativity at all levels: team, operational and strategic?

- Have you developed the personal skill of listening to other people's good ideas, building on them and developing them as far as they can go?

- Are you tactful with people's feelings when it comes to appraising critically their ideas, suggestions and proposals?

- Does your organization have nets, such as suggestion schemes and quality circles, to harvest the creativity of your people?

- When seeking to introduce desirable change do you always:

- plough the ground?

- market your ideas?

- have a practice run?

- make change incremental?

- communicate to innovate?

- Have you created a climate or atmosphere in your organization that positively encourages and supports innovation at all levels of desirable change?