Sixteen Greatest Ideas for Effective Managership

Idea 1: A brief history of managing and being a manager

It is the mark of the educated person that in every subject he looks for only so much precision as its nature allows.

Aristotle, Ethics

Manager and managing are impressive words in the English language, but that shouldn't prevent you from being clear about what they mean. By clear thinking you can avoid a lot of the confusion and empty modern disputes in business schools about, say, the difference between being a manager and being a leader.

Let's begin by trying to work out together what a manager is. The simple and most general definition is a manager is a person who manages something So what does the verb ‘to manage’ mean?

The clue lies in the word itself. It descends to us from a combination of two Latin words: manus, hand, and agere, to do. Originally, then, to manage was to handle something, usually for a purpose and with dexterity or skill.

The management of horses was an early use in the sixteenth century. Indeed, the very first School of Management to open its doors in London in Shakespeare's day was attended by horses!

The skilful handling of any implement, ranging from a full-rigged sailing ship to a pencil, falls within the broad compass of this early definition.

Then the verb was applied to something far less precise, the managing of affairs of one sort or another. Affair, from the French faire, to do, is a very general word: it means something that is to be done, a matter to be attended to, a concern, business or professional dealings or public matters. Vague as business affairs are as objects of managing, if we know the context, we are usually pretty clear in understanding what this entails.

Eventually in the slow-moving English language the noun manager followed the verb, like a cart trundling behind a horse. In the seventeenth century, for example, the members of either House of Parliament who were appointed to oversee some specified affair or piece of business that spanned the functions of the two Houses were called managers.

Finally, manager found its way into the expanding industries of the Industrial Revolution as a job title for those who occupied offices or positions below the owners but above superiors and foremen.

The first recruits for the offices of manager were drawn from the ranks of practical engineers and accountants. Their professional backgrounds would colour thinking about management for almost two centuries.

What did these managers do? The general word for professionals in their position was administration. Their form of administration was distinguished from other kinds, such as public, school or hospital administration, by calling it industrial administration.

As organizations grew larger, a distinction developed between higher and lower administration. The highest grade of the British Civil Service, for example, was the administrative grade.

In the field of commerce (industrial and financial businesses) the former came to be called business administration; hence a relic of those days, the degree of MBA (Master of Business Administration).

In what ways is being a manager different from being an administrator?

In what ways is being a manager different from being an administrator?

Idea 2: Case study – Henri Fayol

One of the earliest attempts to map the role and functions of the modern manager was made by a Frenchman. Henri Fayol's Administration Industrielle et Generale (1916) is still regarded as a landmark in thought about management.

Fayol began as a mining engineer. He then moved into research geology and in 1888 joined a medium-sized coal, iron and steel company called Comambault as director. Comambault was in difficulty, but Fayol turned the operation round. On retirement he published his work, a theory of how to organize commercial business operations and administer them effectively.

Fayol divided a business into six core activities: technical, commercial, financial, security, accounting and administration. The latter he analyzed into just five functions:

- Forecasting and planning: looking ahead and drawing up plans for action.

- Organizing: dividing up work and allocating duties; building up a structure for the undertaking.

- Commanding: maintaining activity; giving orders or instructions so that policies are carried out.

- Controlling: settng up policies, rules or standards; checking that everything done conforms to these; taking corrective action where necessary.

- Coordinating: binding together, unifying and harmonizing activity and effort.

Why commanding?

For us the word command has military overtones. It suggests an old-style ‘command-and-control’ style of management. It is worth recalling that when Fayol's book was published in France in 1916, the northern part of the country was a battlefield of mighty armies. The military was then the dominant institution of the day, and as such it was influential for all other types of organization.

The military model

‘The leaders of Industry’, Thomas Carlyle wrote in 1843, ‘are virtually Captains of the World’. Great engineering projects, such as those undertaken by Isambard Kingdom Brunel in England, and the rise of big business organizations in America created new armies.

Their captains or generals were men like Andrew Carnegie or John D Rockefeller. Business executives or managers were the new officer class; supervisors supported them as the senior ‘non-commissioned officers’, with foremen (from fore, being in front) as the corporals, or leaders of ten.

The limitations of command

Command emphasizes the official exercise of authority. It is not a word that touches the strings of the heart or mind.

Fayol was aware of this fact. Although in those days there was no word for leadership in the French language (it was imported recently from English), Fayol expected the general manager or director to seek willing obedience. A director, he said, should:

- Have a thorough knowledge of employees.

- Eliminate the incompetent.

- Be well versed in agreements binding the business and its employees.

- Set a good example.

- Conduct periodic audits of the organization using organizational charts for the purpose.

- Bring together his chief assistants for meetings to ensure unity of direction and focusing of effort.

- Not become engrossed in detail.

- Aim at making unity, energy, initiative and loyalty prevail among all employees.

Institutions and organizations are designed to run on command and compliance; leadership is far too unpredictable a fuel to be relied on alone. However, wise armies – and wise businesses – do all in their power to ensure that those who occupy leadership positions are able to secure the willing cooperation of their people.

Your example is stronger than your orders.

Idea 3: Understanding Groups and Organizations

A picture is worth a thousand words.

Chinese proverb

Working groups are more than the sum of their parts: they have a life and identity of their own. All such groups, provided that they have been together for a certain amount of time, develop their own unique ethos – their group personality.

The other side of the coin concerns what groups share in common as compared with their uniqueness. They are analogous to individuals in this respect: different as they are, working groups have in common certain needs.

There are three areas of need present in all working groups and organizations. They are:

- the need to achieve the common task

- the need to be held together or maintained as a team

- the needs that individuals bring into the group by virtue of being human beings.

Task need

Work groups and organizations come into being because there is a task to be done that is too big for one person. You can climb a hill or a small mountain by yourself, but you cannot climb Mount Everest on your own – you need a team for that.

Why call it a need? Because pressure builds up a head of steam to accomplish the common task. People can feel very frustrated if they are prevented from doing so.

Team maintenance need

Many of the written or unwritten rules of working groups are designed to promote unity and to maintain cohesiveness at all costs. Those who rock the boat or infringe group standards and corporate balance may expect reactions varying from friendly indulgence to considerable pressure.

This need to create and promote group cohesiveness I have called the team maintenance need.

Individual needs

Thirdly, individuals bring into the group their own needs, not just the physical ones for food and shelter (which are largely catered for by the payment of wages these days) but also the psychological ones: recognition; a sense of doing something worthwhile; status; and the deeper needs to give to and receive from other people in a working situation. These individual needs are perhaps more profound than we sometimes realize.

The three circles interact

The three circles model suggests quite simply that the task, team and individual needs are always interacting with each other, for good or ill.

To understand this dynamic positive or negative interaction, think of the knock-on effects in the other two circles of any change in one circle.

For example, if a group achieves its task, that in itself will tend to draw its members closer together.

On the negative side, if a group lacks harmony and has internal communication problems, it will be less capable of effective work on the common task, as well as being less likely to meet the social need of individual members.

Each of the circles must always be seen in relation to the other two. As a leader you need to be continually aware of what is happening in your group in terms of these three circles.

Each of the circles must always be seen in relation to the other two. As a leader you need to be continually aware of what is happening in your group in terms of these three circles.

Idea 4: The central functions of leadership and management

Not the cry but the flight of the wild duck leads the flock to fly and follow.

Chinese proverb

In order for the three overlapping areas of needs to be met, certain functions have to be performed. A function is what you do, as opposed to a trait or characteristic, which is what you are.

The generic role of leader can be refracted into three broad functions: achieving the task, building and maintaining the team and motivating or developing the individual. It can be further refracted into rather more specific functions. The diagram shows an indicative list.

Idea 5: Eight functions for brilliant managers to master

These functions need to be performed with excellence and this is achieved by practising them so that your skill level increases. Remember that functions don't become skills until you make them so. This takes hard work and persistence. But did I ever say that becoming a brilliant manager would be easy?

Which is my strongest function? And which is the function I most need to improve?

Which is my strongest function? And which is the function I most need to improve?

Idea 6: Leadership (1) and leadership (2)

He had no aptitude for leadership in any direction, either good or bad.

Greek historian Plutarch, on Gaius Antonius,

younger brother of Mark Antony

Few words have caused as much confusion in modern times as leadership. It is no good consulting the internet for clarification: if you Google ‘leadership books’ there are more than 35 million entries! So we need to think about the issue together, as if from first principles.

The first part of the word is clear enough. The Anglo-Saxon root of the words lead, leader and leadership incidentally, is laed, which means a path or road. It comes in turn from the verb leaden, to travel or to go, especially the causative form: to cause or make to want to go. It implies keeping people together or in order, too; a leader is more than a mere guide.

The Anglo-Saxons extended the word to refer to the journey that people make on such paths or roads. Being seafarers, they also used it for the course of a ship at sea. A leader was the person who showed the way. On land he would do so normally by walking ahead, or taking the lead as we say. At sea he would be the navigator and steersman, for in those days the same person performed both functions.

It is the second part of the word – the suffix ship – that has confused thinkers and writers, for it has two distinct but hidden meanings in English:

- Leadership (1) – The role, office or position of a leader; collectively, the leadership of a nation, profession or organization (as in directorships).

- Leadership (2) – Ability or skill in a certain capacity (as in craftsmanship or penmanship).

It is quite possible for institutions and organizations to survive, as many do, if those who occupy leadership (1) roles or offices are devoid of leadership (2). They get by on command, the lawful use of authority and compliance. Nevertheless, they seldom flourish.

Idea 7: Leaders and followers

‘She still seems to me in her own way a person born to command,’ said Luce…

‘I wonder if anyone is born to obey,’ said Isabel.

‘That may be why people command rather badly, they have no suitable material to work on.’

Ivy Compton-Burnett (1892-1969), British novelist

You can't be a doctor without patients, a teacher without students or a king without subjects. Nor can you be a leader, or a manager, without followers.

Followers, of course, is being used metaphorical. It is a mistake to take it too literally. True leaders create partners, not followers.

There are no bad soldiers, only bad officers. When I joined the British army to do National Service I picked up that military proverb. It may not be quite true – there have been bad soldiers – but it is a very good maxim to teach young officers. It invites them to avoid blaming their mistakes on their soldiers, and instead to work on improving themselves.

A complementary proverb for followers might be: There are no bad officers, only bad soldiers. What do you think?

No leader is perfect. Mature, wise and skilful followers accept that fact and work with their leaders; they build on their strengths and make good their deficiencies.

In any organization you are always in three roles: leader, team member and colleague (or, to give these their Latin-derived names, superordinate, subordinate and coordinate). Your task is to achieve excellence in all three roles.

‘Rome showed itself to be truly great, and hence worthy of great leaders’ wrote Plutarch in his biography of Cato the Elder. Is your organization ‘worthy of great leaders’ ?

‘Rome showed itself to be truly great, and hence worthy of great leaders’ wrote Plutarch in his biography of Cato the Elder. Is your organization ‘worthy of great leaders’ ?

Idea 8: What gives you the right to manage?

A sage's question is like half the answer.

Chinese proverb

In any field of study or inquiry it is important to formulate the right question. Here it is:

Why is it that one person is perceived to be, and accepted as, the leader in a group rather than anyone else?

Traditionally, there are three routes to answering that question and, like paths on a mountain converging on the summit, ultimately they blend into one.

- Qualities – A person becomes a leader because they have certain innate qualities, the qualities of leadership. They are born to lead and will do so in any context.

- Situational – Leadership depends on the context: in one context a person will be accepted as leader, in another they may not. Leadership goes to the one most suited for the situation, especially by knowledge.

- Group or functional – Leadership is a role within a group. It is the one who is most able to enable a group to achieve its task while maintaining unity who is accepted as leader.

In its active form the three circles model serves as a catalyst. It invisibly blends together the three main approaches to understanding leadership – qualities, situational and group or functional – into one integrated whole.

A leader is the kind of person (qualities), with the appropriate knowledge (situational), who is able to provide the necessary skills (functions) to enable a group to achieve its task, to hold it together as a cohesive team and to motivate and develop individuals; the leader does so with the right level of participation from other members of the group or organization.

This cumbersome sentence is clearly not meant to stand alone as a definition, but it is one way in which I can pull the threads together for you.

By necessity, leading and managing have to be something of a team effort, especially as you move into the higher levels of leadership. Or, to put it another way, your team becomes one composed of leaders within the organization.

You need to fulfil or master the generic role. Your style, which is an expression of you, will then emerge naturally as you apply yourself to the simple functions. Leadership and management consist mainly of doing some relatively simple and straightforward things, and doing them extremely well.

At whatever level you find yourself, you should think and communicate about the task in terms of values as well as needs. Then the common purpose will tend to be in harmony with the values of your team and of all the individuals in the organization – including your own.

Idea 9: What you have to be or become

I cannot hear what you say, because what you are is thundering at me.

Zulu proverb

We do now know some things about the personal qualities or characteristics that good managers ought to and tend to possess.

Although one cannot draw any hard-and-fast lines in this area, I make a rough working distinction between what could be called representative and generic qualities.

The former are more rooted in a given working situation; the latter are found more widely across the spectrum, in most leaders and at all times in history.

Representative qualities

Managers tend to possess and exemplify the qualities expected or required in their working groups. Physical courage (which appears on most of the lists of military leadership) will not actually make you a leader in battle, but you cannot be one without it.

If you aspire to be a sales manager, you should possess in large measure the qualities of a good salesperson. The head of an engineering department ought to exemplify the characteristics of an engineer, otherwise they will not gain and hold respect.

Thus, a manager should mirror the group's characteristics. You cannot expect others to show qualities in their daily work – the compassion, kindness, warmth and courtesy of a good nurse, for example – if you as their leader do not show them yourself.

It all comes back to leading by example. Do not be like the hypocrite who tells others to do what you don't practise yourself.

Some generic qualities

I have been lucky over a long career to meet many leaders in many different fields, and I have heard or read about a legion of other ones too. Certain personal qualities have begun to stand out in my mind as being common, if not general or even universal. They are both qualities that effective managers tend to have and qualities that globally people now look for in their leaders.

When the author John Buchan, then Governor-General of Canada, gave what I regard as a great lecture on the subject of leadership at the University of St Andrews in 1930, he offered his own list of leadership qualities, although he wisely added: ‘We can make a list of the moral qualities of leaders but not exhaust them’ (my italics). I agree with him.

Therefore you should take the list I offer you below as indicative rather than exhaustive. It is open ended and you are free to add or subtract.

- Enthusiasm

- Integrity

- Toughness or demandingness and fairness

- Warmth and humanity

- Humility

Exercise: Leadership qualities

Take a piece of paper and write across the top the names of two individuals know to you personally whom you regard as leaders.

See if you can explore the above qualities in them by giving them a mark out of ten for each quality.

Can you think of an episode where a particular quality was exemplified?

Idea 10: What you have to know or learn

There is a small risk that leaders will be regarded with contempt by those they lead if whatever they ask of others they show themselves best able to perform.

Xenophon, Greek historian

Who becomes a leader of a particular group engaging in a particular activity is always related to the situation. Situation here can refer either generally to the field of work or more particularly to a situation that arises, such as a crisis or opportunity.

Focusing on this situational dimension emphasizes the importance of knowledge in the person selected for the role of leader – knowledge relevant to the particular field.

Broadly speaking, there are three kinds of authority at work:

- The authority of position – job title, badges of rank, appointment

- The authority of personality – the natural qualities of influence

- The authority of knowledge – technical, professional

Whereas leaders in the past tended to rely on the first kind of authority – that is, they exercised mastery as the appointed boss – today managers have to draw much more on the second and third kinds of authority.

Professional or technical knowledge is not the whole story. It is especially important in the early stages of your career, when people tend to be specialists. As your career broadens out, however, more general skills, such as communication and decision making, come into their own. You need to acquire these general skills, for technical knowledge alone will not make you into a brilliant manager.

Case study: Michael

Michael, aged 36, had a brilliant career as a ‘back-room boy’ in the accounts department of a British pharmaceutical company. He had passed all the examinations and specialized in tax matters, winning himself a solid reputation. He had been with the same firm for 12 years.

On situational grounds Michael was the ideal man to become the manager of his department when the job fell vacant. When that promotion came his way, however, it took him by surprise. He was not prepared for the challenges of being a business leader. The company was in recession and morale in the department was low.

He soon found himself faced with all sorts of problems, in relation to both the department's effectiveness and to people, where his expertise in tax law was of no help. He floundered for a while and then in desperation left the company to set up business on his own as a tax consultant.

How far are the general skills of leadership transferable from one working situation to another? They certainly are transferable, but often the people are not. One reason may be that those concerned do not have the technical or professional knowledge required for another field, and therefore find it difficult to gain the respect of those they are leading.

Authority flows from the one who knows.

Idea 11: Levels of business leadership

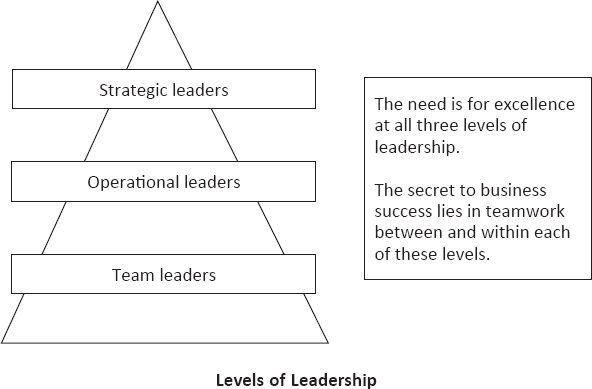

Leadership exists on different levels. Thinking of organizations, there are three broad levels or domains of leadership, as shown in the diagram.

Three kinds of leader

- Strategic – The leader of a whole organization, with a number of operational leaders under their personal direction.

- Operational – The leader of one of the main parts of the organization, with more than one team leader under their control. It is already a case of being a leader of leaders.

- Team – The leader of a team of some 10 to 20 people with clearly specified tasks to achieve.

The same generic role of leader, symbolized by the three circles model, is present at each level. What differs with the levels is the degree of complexity. For example, planning is relatively simple at team level compared with the kind of strategic planning that the chief executive officer of a large organization needs to deliver.

‘An institution is the lengthened shadow of one man,’ wrote American thinker Ralph Waldo Emerson. It used to be assumed that all that was needed was a great strategic leader. This is not true. What all organizations need is excellence of leadership and management at all levels: team, operational and strategic. A simple recipe for organizational success is to have effective leaders occupying these roles and working together in harmony as a team.

Idea 12: Can you manage people?

This isn't a personal question. What I mean is can anyone manage people? You may reply that it's an academic question, because you are managing people. But it's worth thinking about for a moment or two.

The objects of the verb to manage have tended to be one of two things: concrete things like horses, implements and money, or more abstract things like business, affairs or expenditure.

People did occasionally come into the picture. The household administrator or steward, for example, controlled the staff along with the accounts. And Jane Austen in Persuasion talks about a mother managing her unruly young children.

Nevertheless, normally we talk about managing things and leading people.

Have you noticed how management jargon is always trying to turn individuals into things, such as labour or human resources? Only if people are turned into things can they be managed! As the Chinese proverb says, When a cat wants to eat its kittens it calls them mice.

Case study: Man management

The Indian Army invented the phrase ‘man management’. Field Marshal Lord Slim, who served in India, told me that the first manual produced was called Mule Management; mules were widely used for transport. Man Management, the companion manual, was modelled on this.

However Slim, one of the great military leaders of the Second World War, detested the phrase man management. As he said of people in one of his lectures: ‘Like me, they would rather be led than managed. Wouldn’t you?’

Idea 13: You don’t need charisma

Many books that exhort managers to show leadership are really talking about charisma. But that is the last thing you need as a manager.

Webster's Dictionary defines charisma as a ‘personal magic of leadership arousing special popular loyalty or enthusiasm for a statesman or military commander'.

It has since been applied much more widely to leaders in fields other than politics or war. Indeed, it is now in danger of losing all its distinctive meaning and becoming synonymous with public attractiveness: a mixture of good looks, a striking manner, a winning smile and self-proclamation.

So often such charisma proves to be like a coat of fresh paint, which quickly reveals a lasting inadequacy underneath it.

Don't mistake me, there is such a thing as real charisma. Think of Nelson Mandela or his namesake, Admiral Lord Nelson.

Case study: Admiral Lord Nelson

Few commanders or managers have received a better appraisal than young Captain Horatio Nelson. In a letter the Commander-in-Chief Admiral Lord St Vincent wrote:

I never saw a man in our profession who possesses the magic art of infusing the same spirit into others which inspired their own actions… all agree there is but one Nelson.

Thiat is true charisma, but it is not the whole story. Nelson's lifelong friend Collingwood wrote of him:

He possessed the zeal of an enthusiastic, directed by talents which nature had very boastfully bestowed on him, and everything seemed, as if by enchantment, to prosper under his direction. But it was the effect of system, and nice calculation, not of chance.’

His fleet captain Berry wrote:

It was his practice during the whole of his cruise, whenever the weather and circumstances would permit, to have his captains on board the Vanguard, where he would fully develop to them his own ideas of the different and best modes of attack, in all possible positions.

In eight weeks he had made of them a band of brothers. Admiral Lord Hone said of the victory of the Nile:

It stood unparalleled and singular in this instance, that every captain distinguished himself.

In other words, Nelson gave only the simplest directions to his captains, relying on the intelligent responses of his ‘band of brothers’ as they faced particular opportunities. And it worked.

There is no such thing as instant leadership. You cannot get charisma out of a bottle. You can't have the sizzle without the sausage.

Be as systematic as Nelson in doing the right things as a leader – including the more routine and administrative tasks. Master your business. Fulfil the natural role of leader.

Then one day, if you have an ounce of Nelson's enthusiasm, you will discover that your example and your words are having an inspiring influence on others.

Managership is prose; leadership is poetry.

Idea 14: Case study – Xenophon

Those having torches will pass them on to others.

Plato, Greek philosopher

Xenophon, an Athenian writer and military leader, was a disciple and friend of Socrates and a fellow student with Plato in the Socratic circle.

Xenophon has a double distinction: he wrote the world's first book on leadership (read by Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar and Hannibal) and also the world's first book on management.

The Greek title of Xenophon's book on management is Oikonomia, derived from the Greek word for a manager or steward of a large household and its surrounding land. Its English descendant is of course economy. The English also borrowed the French word ménage or manage for husbandry or household administration.

Xenophon was a famous general by the age of 26, a profession he followed in the employ of Sparta. But later in life he had first-hand experience of managing the large and profitable estate that Sparta gave him as a reward, hence his book.

With his Greek sharpened by Socrates, Xenophon looked for underlying principles. He saw, for example, the same principles underlying the conduct of a good general and a good manager. Consider his views and see whether you can answer the questions on p.32.

For some commanders make their men unwilling to work and take risks, disinclined and unwilling to obey, except under compulsion, and actually proud of defying their commander. Yes, and these commanders cause these men to have no sense of dishonour when something disgraceful happens.

Contrast the brave and skilful general with a natural gift for leadership. Let him take over command of these same troops, or of others if you like. What effect has he on them? They are ashamed to do a disgraceful act, think it better to obey and take price in obedience, working cheerfully – each man and all together – when it is necessary to work.

Just as a love of work may spring up in the mind of a private soldier here and there, so a whole army under the influence of a good leader is inspired by love of work and ambition to distinguish itself under the commander's eye. If this is the feeling of the rank and file for their commander, then he is an excellent leader.

So leadership is not a matter of being best with bow and javelin, nor riding the best horse and being foremost in danger, nor being the most knowledgeable about cavalry tactics. It is being able to make his soldiers feel that they must follow him through fire and in any adventure.

So, too, in private industries the man in authority – the director or manager – who can make the workers eager, industrious and persevering – he is the man who grows the business in a profitable way.

On a warship, when out on the high seas and the rowers [lower-class Athenian citizens, not slaves] must toil all day to reach port, some rowing-masters can say and do the right thing to raise the men's spirits and make them work with a will. Other rowing-masters are so lacking in this ability that it takes them twice the time to finish the same voyage. Here they land bathed in sweat, with mutual congratulations, master and oarsmen. There they arrive with dry skin; they hate their master and he hates them.

Exercise

Please answer the following questions:

- What stands out for you in Xenophon's portrait as the essence of leadership?

- Have you experienced personally such an inspiring leader?

- Can you ‘do and say the right thing’ to create willing workers?

Idea 15: Four stages of learning to lead and manage

You are not born a leader, you become one.

A proverb of the Bambileke people in West Africa

If you want to be a brilliant golfer, natural ability takes you only half way there. At that stage you need to learn to do nine or ten things that seem both unnatural and awkward at first. You are unlearning your natural game and having to put the pieces together again in a new, creative configuration. When these new skills become unconsciously habitual, then you are on the final ascent to the summit of excellence.

Learning to play golf is a parable for learning to become an excellent leader. There are four broad phases:

In my experience, the state of unconscious competence seldom lasts very long, otherwise it could degenerate into complacency. You need to keep on learning.

Remember that the word competence, strictly speaking, only implies adequate performance in your role. What you are seeking is not to be adequate, good or even very good – you want to be excellent in your field. And excellence is really always just beyond your grasp.

With luck, you will continually encounter leaders and managers who embody excellence in some particular aspect, function or quality. Learn from them.

Am I a born leader yet?

Am I a born leader yet?

Where do you start? To become an effective leader you should make it your first priority to develop in three areas:

- Awareness – Becoming sensitive to what is happening in groups or organizations, and why it is happening – the ‘group dynamics’ of the situation.

- Understanding – Knowing what leadership function or act is required at any given time.

- Skill – Having the skill to undertake the function effectively in order to achieve the desired result.

Leadership attracts us because it is such an inexhaustible subject. As you go deeper into it you will see that skill and technique are not enough by themselves. As author Joseph Conrad said:

Efficiency of a practical flawless kind may be achieved naturally in the struggle for bread. But there is something beyond – a higher point, a subtle and unmistakable touch of love and pride beyond mere skill; almost an inspiration which gives to all work that finish which is almost art – which is art.

Idea 16: A vision of excellence

Excellence and humility go hand in hand. The best managers are not self-centred egotists. They put their role and responsibilities as leaders first; they emphasize the dignity of their office, not of themselves. They serve people through that role. Their eyes are on the truth, not on themselves.

A leader is best

When people barely know that he exists,

Not so good when people obey and acclaim him,

Worst when they despise him.

‘Fail to honour people,

They fail to honour you’;

But of a good leader, who talks little,

When his work is done, his aim fulfilled,

They will all say, ‘We did this ourselves.’

Lao Tzu, Chinese thinker in the sixth century BCE

The best leaders lack vanity and self- importance.

The best leaders lack vanity and self- importance.