CHAPTER 1

Brand Positioning: The Foundation for Building a Strong Brand

Alice M. Tybout

In 2012, Blue Apron pioneered the meal kit concept—a “dinner in a box” for an entire family that provides a recipe and all its premeasured ingredients in a refrigerated box delivered to customers’ front doors. The founders anticipated that Blue Apron would attract consumers who like to cook but who don’t have time for menu planning and shopping. They also felt that their novel concept would be perfect for those who wanted to cook but lacked confidence in their ability to find tasty, easy-to-prepare recipes.

As this example illustrates, a product or service concept and a targeted group of consumers create the foundation for developing a strong brand positioning. The positioning then articulates how the company would like consumers to think about a brand. It does so by framing the brand in terms of a familiar way of achieving a goal and highlighting a basis of superiority relative to other alternatives in the frame. For example, Blue Apron might be presented as a more efficient alternative to shopping and preparing dinner recipes, because all the meal’s ingredients are delivered to the home in exactly the right quantity. Alternatively, Blue Apron could be presented as a substitute for a takeout dinner that provides more family fun because family members can prepare the meal together using fresh ingredients.

As in the case of Blue Apron, a brand typically can be positioned in more than one way. The manager selects the positioning that she believes is most compelling to the target, provides a sizeable market, and is defensible in the face of competition. The Blue Apron founders chose to launch the brand as a more efficient alternative to shopping and meal prep, because they judged that saving time was important to consumers and that grocery bills provide a larger opportunity from which to “steal” food-spending dollars than takeout. Once the concept of a home-delivered meal kit was established, subsequent entrants used the meal kit category as their frame of reference and sought to differentiate their brands from Blue Apron based on greater ease of preparation (HelloFresh); superior quality and taste (Plated); or healthier, more environmentally friendly meals (Purple Carrot).

This chapter addresses the challenge of developing and sustaining a strong brand positioning in a dynamic marketplace. We begin by examining the representation of a positioning strategy in a positioning statement. Next, we explore approaches to sustaining a brand position over time. In the final section, we assess the potential for repositioning a brand and identify the circumstances in which this strategy is likely to be successful.

The Brand Positioning Statement

A brand’s positioning strategy can be summarized in a formal positioning statement that includes four elements: a target, a frame of reference, a point of difference, and a reason to believe. This statement is an internal document that is used to align all consumer-facing decisions related to the brand (i.e., decisions about elements of brand design, touchpoints, advertising, etc.). To illustrate the structure and content of positioning statements, consider the following statements for Apple and Lite Beer from Miller.

For consumers who want to feel empowered by the technology they use regardless of their level of skill, Apple offers electronic devices that make you feel smarter because they incorporate leading-edge technology that is sophisticated, yet intuitive to use.

For 21-to-34-year-old males with blue-collar occupations, Lite is the great-tasting beer that lets you drink more without feeling filled up because it has fewer calories than regular beer.

In the Apple example, the target is consumers with varying levels of technological skill, the frame of reference is electronic devices, the point of difference is that Apple electronics make you feel smarter than you do when using a competitor’s brand, and the reason to believe is that the brand features superior technology. Similarly, in the Lite example, the target is males 21 to 34 years old, the frame of reference is beer, the point of difference is less filling, and the reason to believe is fewer calories. We begin our analysis of brand positioning by elaborating on each of these four elements of a positioning statement.

Target

The targeted customer for a brand is selected on the basis of many considerations, including the company’s goals, the segments targeted by competitors, and the firm’s financial resources. In the case of a new brand, the product or service may have been designed with the needs of a particular customer segment in mind. For example, the founders of Blue Apron designed their product for consumers who are interested in preparing meals at home but lack the time to plan menus and shop for ingredients. Such consumers may be distinguished from those uninterested in preparing meals at home by demographic factors (gender, age, income, family status, and geographic location) and psychographic factors (activities, interests, and opinions). For example, research might reveal that time-stressed, would-be cooks are likely to be women in dual- career households residing in urban areas who are concerned with health and nutrition. Describing a target in terms of demographic and psychographic features is useful for two reasons: first, it allows the manager to estimate the size of the targeted segment and, hence, whether it is sufficient to meet revenue goals; second, it informs pricing, distribution, and communication strategies that ultimately represent a brand’s position to the target.

Note that the target description in the positioning statement need not enumerate all the features that distinguish it. The target in the Apple positioning statement is described only in terms of its behavioral characteristics (technological skill), whereas the target in the Lite positioning statement is described in terms of demographic characteristics. The objective is to describe the target in sufficient detail so that an appropriate frame of reference and point of difference can be identified.

The target description in a positioning statement often includes insight about the motivation for category and brand use. For Apple, the insight presented in the positioning statement is that the consumer’s goal is to feel empowered to use technology while exerting limited effort. For Lite beer, the positioning statement represents the target’s goal to be indulgent without incurring its costs—the sin without the penalty. For both brands, the consumer insight suggests a consumer pain point that is overcome by the brand. (For more discussion of consumer insight, see Chapter 13.)

It warrants mention that nontargeted consumers may also be attracted to the brand because they wish to emulate the target, or because they view the target as the expert to whom they defer judgment. For example, women seeking a high-performance razor may select the male-targeted Gillette Fusion brand because they perceive men to be more knowledgeable and concerned about shaving than they are. Conversely, men seeking a way to manage dry or frizzy hair may embrace female-targeted hair-management products such as Aquaphor because they perceive the women in their lives to have greater knowledge about hair-grooming products than they do.

Once a brand is established, its image constrains the choice of target going forward. For example, a brand that has historically attracted young, blue-collar men (regardless of whether they were the intended target) is likely to limit the brand’s ability to attract, say, upscale females. We will return to this issue later in the chapter when we discuss repositioning.

Frame of Reference

The frame of reference informs consumers about the goal in using the brand. The most common way to represent a brand’s frame of reference is to specify the category in which it holds membership. Stating that Lite is a beer makes it evident to most people that it is an alcoholic beverage often consumed with friends and food. Along the same lines, when the iPhone launched in 2007, the brand name and advertising focused on announcing the brand’s frame of reference: a phone. This was important because at the time Apple was known for making computers, not phones (https://youtu .be/ohRQonYVcpU). It should be noted that in order to be credible when claiming membership in an established category, a brand must share key features (“points of parity”) with other category members. The assertion that a new brand is a beer would be suspect if it lacked alcohol or carbonation, or if it were best consumed hot.

The frame of reference can also be conveyed by comparing the brand to a different category, as Blue Apron did when it used grocery shopping as the frame. Brands that pioneer a new category employ this approach in an effort to help consumers understand a new concept by relating it to a familiar one. Once the new concept (meal kits) becomes familiar, the pioneer—as well as later entrants, such as Plated—adopts this category as the frame of reference. Like Blue Apron, Uber used an alternative category (taxi) as a frame of reference when it pioneered the ride-hailing concept. Lyft, which followed Uber into the category, relied on consumers’ understanding of ride-hailing and used that category rather than taxis as its frame of reference.

Even when a brand is not launching a new concept, it may use an alternative category because that category might more effectively specify both the brand’s frame of reference and its point of difference. Along these lines, Coke Zero Sugar compares itself to the flagship Coke brand in taste, rather than the Diet Coke brand. This tells consumers that although Coke Zero Sugar’s frame of reference is diet soft drinks, it is at parity with Coke in taste, implying that its point of difference is superiority in taste to other diet brands (https://youtu.be/zTZaZWkwC6E).

Finally, a frame of reference can be communicated by showing the goal that is achieved by using the brand. A humorous ad for eBay in Asia shows a man breaking an antique vase, which distresses his wife. To address this problem, he visits eBay and finds a similar vase, prompting him to celebrate by opening a bottle of champagne. His celebration quickly ends when the cork flies off the bottle and destroys the vase (https://youtu.be/26q6Pi_V6IQ).

Points of Difference and Reasons to Believe

In addition to a frame of reference, a positioning statement requires the specification of a benefit that serves as a point of difference from competition. Benefits are abstract concepts, such as empowering, convenient, and safe. The benefit selected should be important to consumers and one that the brand can own. The choice of benefit depends on a brand’s rank in a category: leaders select the benefit that reflects the main reason for using the category (e.g., Tide cleans best), whereas follower brands reflect a niche benefit (Gain makes clothes smell fresh). A brand’s ownership of a benefit is enhanced when it is supported by a reason to believe, which is concrete proof that gives credence to the claim that a brand has the benefit. The reason to believe that Apple will make the consumer smarter is the series of cutting-edge products the company has produced—iPod, iPhone, iPad, and Macintosh computers. Similarly, the reason to believe that Harry’s bread delivers the benefit “nice and soft” is the image of a child napping with her head on the bread (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Reason to Believe

One way to present a brand’s reason to believe is to feature an attribute. This might entail specifying ingredients: Jif tastes better than other peanut butters because it is made with fresh-roasted peanuts. Or, the attribute might relate to a brand’s equity: Louis Vuitton’s luggage is superior because of the brand’s travel heritage. In addition, for some products, country of origin provides an attribute reason to believe: Perrier is the most refreshing sparkling mineral water because it comes from a spring in Vergèze, France.

The other type of reason to believe involves the presentation of an image—that is, the people involved and occasions when the brand is used. This might entail using a spokesperson with an established and favorable personal brand. Stephen Curry, who is recognized as a professional basketball superstar, serves as a spokesperson for Under Armour basketball shoes, which is a personification of the reason to believe Under Armour’s superior performance point of difference.

In selecting a reason to believe, attributes that are important to consumers are generally considered first, because they are the most compelling way to provide evidence that a brand possesses the claimed benefit. Sales of the Instant Pot programmable pressure cooker grew rapidly because it provided a means of cooking foods more quickly, reliably, and safely than other pressure cookers, due to its programmable feature. The challenge in developing an attribute reason to believe is that in most instances it is imitable. Thus, there is often a small window of opportunity to achieve scale before an attribute point of difference is matched by a competitor, making it into a point of parity. For example, in response to Instant Pot’s success, a number of competitors have entered the programmable pressure cooker category, including Ninja, All-Clad, and Phillips.

The difficulty in sustaining an attribute reason to believe in the face of competition prompts the choice of an image reason to believe in the majority of instances. This approach allows the brand to own the reason to believe by frequently advertising people and/or occasions of product use. Moreover, the choice of an appropriate image can induce substantial growth in sales. Along these lines, the promotion of Dos Equis beer by “the most interesting man in the world” (who did not always drink beer, but when he did, he drank Dos Equis) grew brand sales by 34.8 percent between 2007 and 2015.1

Representing a Point of Difference in Terms of Value

A brand’s point of difference is often represented by the value it provides consumers, which can be assessed in terms of the following conceptual equation:

The numerator of the equation represents benefits in terms of the brand’s physical quality and the emotional response it evokes, whereas the denominator presents the costs in terms of both monetary and time expenditures associated with acquiring and using the brand.

Brands often compete on value in either the numerator or denominator. For example, in the coffee shop category, Starbucks competes in the numerator with superior-tasting coffee (physical) and offering a comfortable destination (emotional). By contrast, McDonald’s and Dunkin’ compete in the denominator: these brands offer coffee quickly and inexpensively for people on the go. The elements of value that are not the basis for differentiation serve as points of parity with other brands in the competitive frame. Thus, Starbucks must avoid the perception that waiting times are inordinately long or that the brand is too expensive, and McDonald’s and Dunkin’ must have good enough tasting coffee and pleasant enough stores lest consumers reject them as options when purchasing a cup of coffee.

Some brands compete on all the benefits represented in the value equation. For example, GEICO’s positioning highlights the insurance brand’s superior quality that consumers can trust (numerator of the value equation), and announces that consumers can save money in as little as the 15 minutes it takes to sign up (denominator). This strategy has the advantage of framing the brand as all-inclusive, which implies that other brands are deficient on some benefit. However, consumers who want to maximize one benefit, say price or quality, may be attracted to a GEICO competitor that emphasizes only what they seek. Thus, a potential liability of the “does it all” strategy is that it may result in other brands dominating on specific elements in the value equation. Even when the claim that the brand “does it all” is warranted, consumers may perceive the claim lacks credibility because it runs afoul of their lay theories about the way the world works (“You get what you pay for”).

A virtue of the value equation in developing a brand’s position is that it links the position to the marketing mix. The physical quality is determined by the brand’s product or service characteristics, the emotional benefits are derived from the consumption experience and the brand image, time costs are linked with the channel of distribution, and monetary costs are determined by the price charged.

Orchestrating the Frame of Reference and Point of Difference

An effective brand positioning strategy requires that the frame of reference, point of difference, and reason to believe are aligned in a way that maximizes demand. Consider Bounty, the paper towel brand that attempted to enhance its growth by adding strength as a benefit to the brand’s greater absorbency equity. The reason to believe was that Bounty was not only effective for quickly cleaning up spills, but also for scrubbing pots and pans and cleaning fish tanks. However, presenting these applications as reasons to believe Bounty’s strength changed Bounty’s frame of reference from paper towels to sponges, which put Bounty in competition with brands such as Scotch-Brite sponges. The sponge category frame of reference is characterized by absorbency and durability, characteristics on which it would be difficult for Bounty to compete. Bounty does dominate Scotch-Brite on the hygienic dimension, in that a Bounty paper towel is a one-use disposable and a sponge is not. However, this point of difference is a point of parity with other paper towels, and it risks undermining Bounty’s absorbency point of difference in relation to other paper towel brands if strength were associated with a lack of absorbency.

The Bounty example illustrates that a brand should select the frame of reference that will attract the most substantial demand for the brand while also providing it with a defensible point of difference. Bounty’s effort to broaden its frame of reference resulted in a different frame becoming salient, which, in turn, obscured Bounty’s point of difference in relation to other paper towels.

Another alignment issue pertains to the fit between the frame of reference and the reason to believe a point of difference. In the positioning statement for Lite beer presented earlier, the brand was represented as tasting great (a way of presenting the beer frame of reference) and as having fewer calories (the reason to believe “less filling”). Here, consideration should be given to whether “fewer calories” is negatively correlated with great taste. If it is, the credibility of the great taste claim is likely to be undermined by the fewer calories reason to believe, which is used to support the less filling benefit.

Testing Your Brand Positioning Statement

Once you have developed a positioning statement, it is useful to check it for clarity, credibility, and distinctiveness. First, show it to people outside the company. For many consumer products and services, friends and family will work well. However, when products require special expertise, targeted customers should be sought. Ask these individuals to read the positioning statement and to indicate the situations in which the brand would be used, why it is claimed to be superior to other options, and whether they believe these claims. If people outside your company cannot grasp the positioning from the statement, it lacks clarity. If they do not believe the statement, it lacks credibility. Second, replace your brand name in the positioning statement with that of a competitor. If the statement still seems reasonable, it lacks distinctiveness. Failing either test indicates that additional work on the statement is warranted.

Sustaining a Brand Position

Once a brand’s position gains traction, in most instances the goal is to sustain that position over time. Some brands have a position that is timeless, and thus sustaining it is straightforward. For many years, Marlboro cigarettes were represented by cowboys, which implied that the brand was for independent individuals who empowered themselves to reach their goals. This campaign was run in the United States for about 50 years. However, for many, additional strategies are needed to sustain a position. Here we discuss several of the more frequently used approaches.

Modern Instantiation

Modern instantiation sustains a position by focusing on the same brand benefit over time, but depicting it in a contemporary context. For example, since its introduction in 1898, the Grape-Nuts cereal brand has been positioned as the natural, ready-to-eat cereal that contributes to health and well-being. However, the context in which this benefit is presented has changed over time to reflect consumers’ view of the meaning of health. In the early 1970s, Grape-Nuts promoted health and well-being with TV advertising featuring naturalist Euell Gibbons as a spokesperson. This reflected consumers’ interest in communing with nature at that time. In the mid-1980s, the context for Grape-Nuts advertising was a consumer’s country house, which mirrored the aspirations and lifestyle of the me generation. In 2013, Grape-Nuts represented health with TV advertising that featured Sir Edmund Hillary—the first person to climb Mount Everest—consuming the brand during a break in a climb, paralleling consumers’ interest in extreme sports as a way of achieving health and well-being.

Switching from Attribute to Image Reasons to Believe

Another means of sustaining a position is to switch from an attribute reason to believe that is no longer news to consumers to an image reason to believe a brand benefit. For example, Extra gum initially promoted its long-lasting flavor, which prompted users to chew it longer, which in turn reduced acid in the mouth, thereby providing some protection against cavities (https://youtu.be/PeTS0sWFSLE). More recently, the brand extended this equity through the characters Sarah and Juan, where Juan used the Extra wrapper and pen to create art, including a drawing of himself asking Sarah to marry him, which she saw exhibited in a gallery (https://youtu.be/upsrMt-JMzA). Thus, Extra’s long-lasting attribute was extended by an image campaign presenting a long-lasting relationship. In the process, the focus changed from personal hygiene to community and sharing.

Laddering

A brand’s point of difference benefit can also be sustained by a laddering-down or laddering-up strategy. Laddering down involves starting with an abstract benefit and enumerating multiple attribute reasons to believe, which are concrete. For example, Volvo used a laddering-down strategy by introducing a variety of attributes, including antilock brakes, a collision warning system, and a blind-spot warning system, all of which serve as reasons to believe the functional benefit of enhanced protection for the driver and passengers. The presentation of various reasons to believe a point of difference benefit sustains news about the brand.

Laddering up involves a more complicated process. First, the brand presents an attribute reason to believe, which is concrete. This attribute implies a functional benefit of that attribute, which in turn implies an emotional benefit, which serves as the basis for the brand’s essence. Volvo employed a laddering-up strategy when it presented the safety attributes noted earlier to support the functional benefit of enhanced protection, which in turn implied the emotional benefit of peace of mind. This emotional benefit was the basis for implying the brand’s essence, which is “Volvo is the brand for people who embrace life.”

Laddering up sustains interest by relating the brand to increasingly abstract and enduring consumer goals. Along these lines, Volvo’s laddering up suggested a contemporary way to express the brand’s commitment to safety. The company noted that 19,000 cyclists in the United Kingdom are involved in accidents every year, and many of these accidents occurred at night when bikers are difficult to see. Further, many luxury car owners (Volvo’s target) also cycle as a hobby. These observations motivated the company to create LifePaint, a paint that is invisible during the day but reflective in the dark, making it easy for drivers to see bicycles painted with it. LifePaint provided news about Volvo’s commitment to safety and preserving lives, and its sale at dealerships resulted in a sales increase of more than 1,000 cars.2

Brand Purpose

A brand positioning statement answers the question, “How do we want targeted consumers to think about the brand in relation to other brands?” A brand purpose statement answers the question, “Why does the brand exist (beyond the goal of financial gain)?” The answer to the “why” question reflects the beliefs and values of the organization. As such, it goes beyond the positioning statement’s focus on a particular target and addresses the concerns that encompass other stakeholders, such as employees and investors. Chapter 2 provides a detailed discussion of brand purpose and its importance. Here, we offer a few observations about the relationship between brand positioning and brand purpose.

In some instances, a brand’s purpose is front and center in the positioning, serving as the basis for differentiation or the reason to believe. Title Nine is a women’s athletic-wear company that follows this approach to positioning. The company develops products specifically for women’s bodies. It began in the 1990s with a line of sports bras for runners and expanded its offerings to include a range of women-specific gear well before Athleta, Lululemon, and others entered the market. Arguably, the availability of Title Nine clothing contributed to more women and girls participating in and succeeding at sports. Named for the landmark Title IX legislation from 1972, which stipulated gender equality and prohibited gender discrimination in education, the brand highlights the value-based goal that the brand established for itself—more girls and women would transform their lives through the achievement and attendant esteem benefits that sports provide. As founder Missy Park noted, “We were working to build a business around the idea that we would change the world, if we could just get our workout in.”3

For other brands, the role of brand purpose is apparent only as a company considers the implications of a brand’s point of difference and reasons to believe. Always is a brand of feminine hygiene pads and panty liners produced by Procter & Gamble. These categories (rather than tampons) are often the ones used by young women when they begin menstruating. The Always brand claims to provide a leak-free, comfortable fit. It supports this claim by featuring demonstrations of absorbency and showing the curved shape of its products in advertising. These attributes provide the emotional benefit of enabling young women to feel confident in coping with the new experience of menstruation. In recent years, Always has extended this equity to present the brand’s purpose—helping young women feel confident in dealing with the stereotypes they face (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VhB3l1gCz2E).

As the Always example suggests, a brand’s positioning that is abstracted to a higher purpose can engage consumers about issues that matter to them. This is especially important in today’s always-on digital world, because brands generate limited news. Yes, a new feature may be added to a brand or an existing one enhanced, but such improvements are infrequent and thus not sufficient to sustain engagement. The outdoor sportswear company Patagonia does a good job of engaging its customers through its brand purpose. The brand sells technical gear and apparel for “silent sports,” which are those that do not have motors but instead connect people with the natural world. Patagonia’s point of difference is its commitment to the highest-quality minimalism in all of its products, with a do-no-harm mentality in both the manufacturing and use of its products. The reasons to believe this point of difference include not only the technical performance aspects of its designs, but also its pioneering use of organic cotton and innovation in using recycled plastic bottles to create synthetic fibers.

The higher purpose of the brand is to facilitate access to and participation in “wild and beautiful places,” and to play an active role in protecting these places. To support this commitment, the company offers grants to climate, environmental, and sustainability groups and uses its web site to promote opportunities to volunteer or otherwise engage with such groups. Recently, Patagonia founder Yvon Chouinard led lobbying and advocacy efforts against reducing the size of Bear Ears National Monument in Utah. Further, the company has sued the U.S. federal government to reverse the decision to reduce the park’s size. The purpose of these initiatives is to provide the opportunity to deepen Patagonia’s connection to its customers around shared goals.

Even brands that might seem to lack an obvious link to brand purpose may uncover one with reflection. Honey Maid graham crackers are positioned as a nutritious snack because they are made with wholesome ingredients, including whole grains and real honey. Honey Maid’s brand purpose is linked to its equity by elevating “wholesome” to celebrate and honor families of all stripes, colors, and definitions. Honey Maid uses social, digital, and traditional media to showcase LGBTQ and racial inclusivity in specifying what it means to be a wholesome family. Honey Maid even turned the anti-gay response to its TV ad featuring gay dads and biracial families into digital content (coupled with the hashtag #thisiswholesome) that transformed hate into love (https://www .youtube.com/watch?v=cBC-pRFt9OM).4

Authenticity in walking the talk proved critical in making Honey Maid’s brand purpose more than just an assertion. The company’s actions spoke to the authenticity of its elevated version of what wholesome means. However, when positioning at the level of purpose, a brand should recognize that it will be held to the standard espoused, and that all employees must walk the talk. Starbucks, a firm committed to social justice, was taken to task in spring 2018 when an employee at a Philadelphia store acted in a manner suggesting racial bias.5 Had the same deplorable incident occurred at say, 7-Eleven or Dunkin’, one suspects it would have received less attention in the press and provoked less outrage by customers.

Repositioning a Brand

When a brand position is developed, the goal is to sustain it over time. However, certain circumstances may require the repositioning of a brand, which may involve changing the frame of reference or reframing. This typically is necessary when a brand is the first entrant in a category.

Consider the introduction of Miller Lite, which was the first successful light beer in the United States. Its frame of reference was regular beer, which had great taste, and its point of difference was less filling, which was supported by fewer calories than other beers as the reason to believe. The entry of Bud Light resulted in consumers changing their perception of the frame of reference from regular beer to light beer. This new frame changed Miller Lite’s point of difference—less filling—to a point of parity and thus part of the frame of reference. To differentiate the brand, Lite had to develop a new point of difference. Bud Light beat Miller Lite to the punch by promoting its superior taste, which was supported by the fact that Budweiser’s base brand was the “King of Beers.” By focusing on its superior taste, Budweiser adopted the point of difference that is a key determinant of beer choice, leaving Lite to find a niche benefit. Blue Apron faces a similar challenge with the emergence of other brands in the meal kit category.

Repositioning is also warranted when a brand’s position is too broad to be supported by the reason to believe. For example, Aleve was positioned as a convenient analgesic that effectively relieved pain and only needed to be taken every 12 hours. However, this broad frame of reference did not fit with the brand’s reason to believe. In fact, for consumers, 12-hour dosing implied slow acting rather than convenient. To align the reason to believe with the frame of reference, Aleve was repositioned as the brand that relieves arthritis pain. Narrowing the position in this way made the convenience of infrequent dosing a compelling reason to believe for those suffering chronic pain. Although this frame narrowed the number of people being targeted, Aleve was relevant to the 40 million people in the United States who suffer with arthritis. Moreover, it set Aleve apart from Advil and Tylenol, which require more frequent dosing to sustain pain relief.

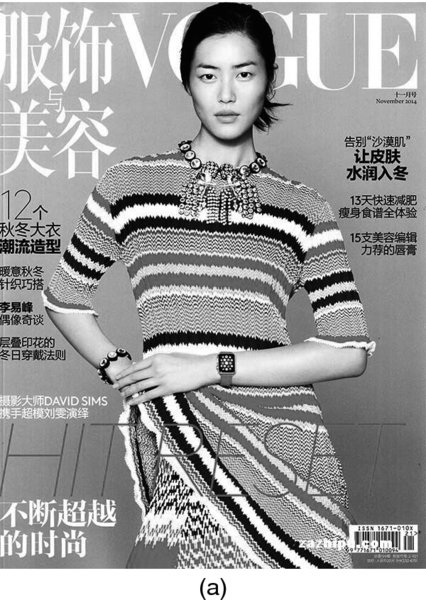

Another situation in which repositioning can be achieved readily occurs when the initial position failed to gain traction. For example, Apple introduced its first-generation watch as a fashion item whose band could be changed to accommodate different wearing occasions (see Figure 1.2a). This position was changed a year later when the watch was reframed as a functional device for those interested in health and fitness (see Figure 1.2b). This repositioning was successful because the Apple Watch never gained traction as a fashion accessory but was relevant for monitoring health and fitness.

Figure 1.2 Apple Watch Initial (a) and Revised (b) Positioning

Changing or sharpening a position may also be appropriate and feasible when the original positioning has been diluted due to licensing or other growth-motivated activities, or the brand has been “hijacked” by consumers who are not the desired target. Such was the case for Burberry in the early 2000s. Loose control over licensing deals resulted in the brand name appearing on a wide range of products (including chocolate) at price points that varied dramatically. Further, football (soccer) hooligans (“chav”) had embraced the brand and sported caps and umbrellas with the distinctive plaid pattern (often counterfeit) at games where brawls in the stands were common.

The repositioning of the Burberry brand, which was led by Christopher Baily and Angela Ahrendts, involved regaining control of licensing and distribution, dialing back the use of the Burberry plaid in the apparel, stepping up innovation in design, using supermodel Kate Moss and other celebrities in advertising, and creating a strong online presence. These activities drove sales growth for a decade and reestablished Burberry as a luxury brand that blends fashion and function in a uniquely British way. In late 2017, the new CEO, Marco Gobbetti, who was recruited from Céline, announced his plan to reposition Burberry as a super luxe brand, similar to Dior, Hermès, and Gucci. The jury is out as to whether this repositioning will succeed, but the brand’s heritage in functional outdoor attire may limit how far upscale it can move. At a minimum, Old Navy’s experience serves as a cautionary tale about the difficulty in moving a brand up to a higher fashion or luxury tier.

Old Navy was a brand for value-oriented families interested in purchasing casual clothing. Old Navy’s reason to believe was the unusually wide selection of T-shirts, jeans, khakis, and other casual attire. When a new chief marketing officer was hired, a line of trendy but inexpensive clothing was introduced with the goal of appealing to young, fashion-conscious women. However, the space allocated to the trendy items reduced the breadth of selection that was central to Old Navy’s position and frustrated its core consumers. Old Navy sales declined dramatically—over 20 percent in several months. Similar, equally disastrous results occurred when new CEOs at JCPenney and Lands’ End attempted to reposition those brands as more fashion-forward. Existing customers were not impressed, and not enough new customers were attracted to offset the defecting old customers.

In sum, once a brand has traction in its current position, repositioning is a strategy of last resort, as it is likely to alienate the brand’s core users. It may also conflict with the prior brand position and thus confuse consumers. And even if these issues do not arise, repositioning typically takes considerable time and financial resources. Nevertheless, modest changes in a position are sometimes warranted to better align a brand’s frame of reference with its point of difference and reason to believe, as was described for Aleve. Moreover, when a brand is the first entrant in a category where the frame of reference is typically another category, repositioning is generally required, as we noted for Lite beer and Blue Apron. Finally, when a brand has not gained traction in a position, adopting a new frame of reference may be warranted, as was the case for Apple Watch. However, consideration should first be given to the strategies for sustaining a position discussed earlier.

Summary

A brand’s positioning serves as the foundation for all brand-building activities. It is summarized in a statement that captures the target, frame of reference, point of difference, and reason to believe the point of difference. This statement is a succinct summary of how the brand will compete in the marketplace and guides all decisions related to the marketing mix. Ideally, the positioning endures over decades, though changes will be needed to maintain relevance to new generations of the target and to maintain customer engagement. A variety of strategies are available to help achieve this goal, including modern instantiation, laddering, and brand purpose. Nevertheless, repositioning is sometimes necessary. This is likely to be the case when a new category is being established and the initial frame of reference is, of necessity, an alternative category. Repositioning may also be necessary when a brand position has been diluted or abandoned through undisciplined tactics or the market opportunity for the current position is limited. However, repositioning an established brand is always a challenge, because consumers’ perceptions of it are slow to change. Repositioning failures outnumber the successes, which highlights the importance of getting things right the first time!

Alice M. Tybout is the Harold T. Martin Professor of Marketing and a past chairperson of the Marketing Department at the Kellogg School of Management. She is also co-director of the Kellogg on Branding Program and director of the Kellogg on Consumer Marketing Strategy Program at the James L. Allen Center. She is co-editor of two previous Wiley books, Kellogg on Branding (John Wiley & Sons, 2005) and Kellogg on Marketing, 2nd ed. (John Wiley & Sons, 2010). She received her BS and MS from Ohio State University and her PhD from Northwestern University.