CHAPTER 15

Measuring Brand Relevance and Health

Julie Hennessy

Brands are assets of enormous impact and value. They are the lenses through which consumers see product features and decide whether they are interesting enough for further consideration. Brand stewards, from entrepreneurs to corporate managers, spend enormous effort and resources to support their brands and keep them strong and preferred. So how should we measure the productivity of these efforts? How do you track, tend, and measure the health and vitality of your brand?

Executives have asked this question for years, and the answer is not getting any easier to define. When we thought of brands as logos, trade dress, and intellectual property, the focus was on legal protection of our assets, control over their use, and defense against encroachments on our territory. We fought back when competitors got too close and imitated our brand assets, or even when our brand marks were used incorrectly within the company. To this day, there is swift reaction when a franchisee decides to alter the color of McDonald’s Golden Arches, or a dealer gets too creative with the iconic John Deere logo. But the focus of today’s efforts to protect the brand has shifted a bit, and digital access to voluminous data will accelerate the changes in how we track brand value.

A story illustrates this point. Over 20 years ago I worked for the packaged food giant Kraft and had responsibility for its iconic Kraft Macaroni and Cheese brand. Within this brand franchise, Kraft earns higher profit margins on the specialty-shaped, macaroni-like spirals and SpongeBob Shapes than the original tube-shaped variety. For years, Kraft has experimented with new shapes for the product. During my tenure, we had the brilliant idea of putting Mickey Mouse-shaped macaroni in the box. After all, mice love cheese, and Kraft has long been deemed the “cheesiest”—a match made in heaven. Out we flew to Southern California to meet with Disney executives and propose a cheesy partnership. Unfortunately, a deal did not result, and no mice ever entered the Kraft Mac and Cheese boxes (at least not on purpose). At the time, Disney was uncomfortable with the idea of people “eating” Mickey Mouse and feared that Mickey would be overexposed as a result of too many licensing deals.

But while at Disney, we caught a glimpse of the voluminous Mickey Mouse “brand standard”—page after page of documentation and guidelines that dictated and delineated the rules for Mickey Mouse. It included what he could wear, what he would say, and even the nature of that oh-so-ambiguous relationship he has with the object of his affection, Minnie Mouse. Clearly, Disney took brand control and protection very seriously.

Then, a year or so ago, I had another opportunity to discuss branding with a Disney executive. I told him about that long-ago meeting, and we laughed about the fact that Mickey Mouse had found himself in many, many food products in the intervening years. Finally, I asked about the old Mickey Mouse brand standard: the document that set the rules and boundaries for the brand that is Mickey Mouse. The executive sighed and commented, “That was a different era.” He continued, “Today, in a world of consumer-created content and easy ‘cut and paste,’ we figure that we control a very small fraction of the images of Mickey Mouse.”

While official licensing deals are still plentiful and lucrative, this illustrates the point that the days of controlling an asset and its every use are over. Today, we participate with consumers, and even competitors, in the use, interpretation, and protection of the brands we manage. As is true in so much of marketing today, managing brands is as much a conversation as a one-way dictation, where we must spend as much time asking consumers what a brand means as telling them what to think.

In this chapter, we will talk about today’s new definition of the brand, and discuss some cutting-edge techniques for making sure we really hear the voice of the customer in our efforts to track and measure brand value. We will discuss a model for understanding strategies for building a brand, from repositioning to brand extensions. And, we will discuss how the connected digital world impacts the challenges of brand tracking.

Brand Measurement Techniques

If we now think about brands not as logos and trademarks but as sets of associations in the minds and hearts of individuals, the challenge of measuring and tracking the health of brands fundamentally changes. First and foremost, all sorts of entities that we didn’t think of as brands before can now be studied. Certainly, companies such as Disney, McDonald’s, and Nike are still brands. But locations—such as Las Vegas, Paris, and Dubai—are also brands with rich associations. People are also brands—political figures such as Donald Trump, entertainers such as Beyoncé, and leaders such as Pope Francis. Any entity about which individuals have strong and plentiful associations can be thought of and measured as a brand.

But how do we measure these nebulous and changing sets of associations in a way that is useful to the owners and managers of these brand equities? It is quite a challenge. Traditionally, brand monitoring and measurement has been conducted in two dominant ways: measurement of awareness and tracking of brand attitudes. Both of these methods are still valid today, so it is worth the time to discuss their use and limitations.

Awareness Tracking

Awareness tracking is the most frequently executed measure of brand health and relevance. Many executives think of this metric in a very simple way: they think of high-awareness brands as valuable and low-awareness brands as either troubled or underdeveloped. While awareness is still a relevant metric when considering a brand’s strength and health, this simplistic “more awareness is always better” thinking is not particularly accurate or useful. Understanding awareness levels is a piece of the puzzle needed for assessing a brand’s health, but it is not enough as a stand-alone measure. In fact, high brand awareness in itself can actually be a challenge or impediment to success.

Think of awareness as the likelihood of consumers knowing or recognizing your brand’s name. Certainly, it is impossible for someone who has never heard of you to love or want you. In that way, awareness is a necessary precursor for consideration, trial, purchase, or advocacy. Thus, awareness is the first level of most brand marketing funnels (see Figure 15.1).

Figure 15.1 A Typical Marketing Funnel

However, in some situations, awareness can also be an impediment. If everyone already knows your brand, it is harder to generate growth. And, if you are unfortunate enough to manage a brand that everyone already knows and thinks poorly of, you may be facing the toughest of all brand challenges—changing attitudes about a brand that consumers know well and dislike or distrust. High levels of awareness make the challenge of changing brand attitudes particularly difficult and sometimes even impossible. Thus, awareness can be a friend or foe.

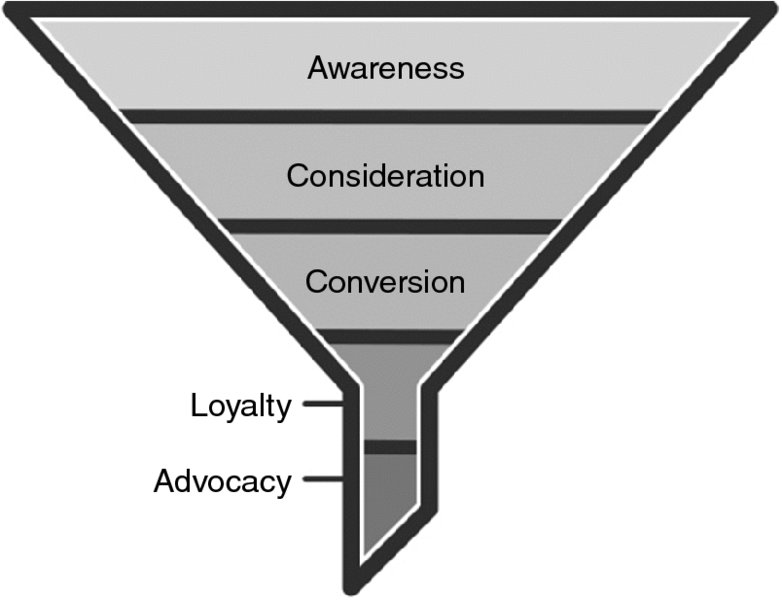

Companies measure brand awareness in two ways—aided awareness and unaided awareness. In an aided awareness measurement study, the consumer or respondent is presented with a list of brands and asked to check which ones he or she is familiar with. This, in effect, is the “aiding” of aided awareness. While aided awareness measures can be useful, the prompting done by showing consumers a list of brands in some ways confounds the testing. Aided awareness measures, for that reason, often overstate actual awareness.

Therefore, the more useful way of measuring awareness is unaided awareness. In an unaided awareness study, a respondent is given a category—such as hotels, athletic shoes, or candidates for president. They are then asked, without any hints or prompting, to list the brands that they can think of in that category. This type of unaided brand awareness is a true measure of actual brand awareness, and the order in which consumers list brands is a reasonable proxy for which are most top of mind (see Figure 15.2).

Figure 15.2 Questions to Measure Awareness

Attitudinal Brand Tracking

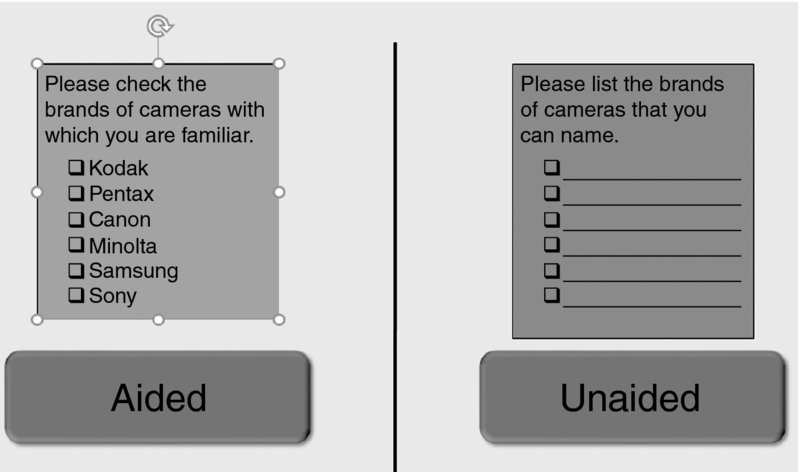

The second form of traditional brand measurement is attitudinal brand tracking. Here the effort moves beyond just understanding whether a consumer knows a brand or not and shifts to assessing what the consumer knows, thinks, or feels. Many companies conduct some sort of attitudinal brand tracking in order to take the pulse of what consumers are thinking about their brands. In these surveys, which may be fielded every few years or as frequently as weekly, consumers are asked to agree or disagree if a predetermined set of attributes is descriptive of a brand. This list of attributes is usually conceived by the managers of the brand and is usually fairly aspirational in nature. They are the brand managers’ words, not necessarily the consumers’ words (see Figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3 Example of Attitudinal Tracking of McDonald’s

Feedback from this sort of consumer survey can certainly be useful, especially if there is the ability to compare responses to the survey by current users of a brand versus nonusers over time, and if there is data on both the brand and its direct competitors. However, there is one factor that is missing in such a survey. Not unlike the criticism of measures of aided awareness, this sort of survey data does a weak job of capturing the consumers’ unvarnished thoughts and feelings. The survey itself suggests some thoughts that the consumer should have and not others. We get no sense of the words that consumers would use on their own to talk about brands.

Asking Open-Ended Questions: A Less-Biased Way To Measure Brand Associations

For these reasons, my research in the past few years has focused on a method for collecting brand associations without this bias. Consumers (or nonconsumers) of a brand are simply asked an open-ended question such as, “What comes to mind when you think of the brand__________?” followed by, “What else_____? What else____?” Data is tabulated across large enough groups of respondents to be useful and reliable, and yet the data comes in the form of respondents’ own words, thoughts, and feelings. Data is frequently collected online, to allow consumers to express themselves freely and without reservation. The recent results of these studies have often been surprising and illuminating.

For instance, surprisingly enough, Toyota drivers’ associations of “safety” increased as Toyota experienced problems and garnered bad press about unintended acceleration and recalls. While counterintuitive, consumers needed to believe that their own Toyota cars were safe to justify the daily decision to keep driving it. This enhanced belief in their own Toyota’s safety explains why Toyota’s repurchase and loyalty measures did not suffer after public scrutiny and multiple recalls.

Similarly, while it was conventional wisdom that 2016 U.S. presidential candidate Hillary Clinton would have a clear advantage with women voters, it was clear that a significant segment of women voters found her to be unlikeable. In fact, women were more likely than men to describe her with negative adjectives. This was a first window into the fact that Clinton would experience a problem with women’s support in the election.

Likewise, as the press talked about the likely demise of the Volkswagen brand after the Volkswagen emissions scandal, it was clear that consumers, especially Volkswagen drivers, were just as likely to see the firm’s behavior as evidence of the sophistication of German engineering skill. While some consumers undoubtedly thought that the firm had acted in an unethical manner, others focused on how smart and crafty it was to create a “defeat” device in the emissions system.

Uber is another example. Collecting open-ended consumer brand associations provides insight into how the brand was impacted by the behavior of its controversial ex-CEO, Travis Kalanick, who resigned in 2017 over allegations of ignoring sexual harassment at the company. It also sheds light on how the scandal impacted its competitor, Lyft. Open-ended brand association tracking in 2017 and 2018 indicated several interesting findings about the impact that negative stories about Uber and its CEO were having on the Uber brand, competitive brand Lyft, and the category of ride-sharing as a whole. Uber, it turns out, was carrying a sea of negative associations. When asked what came to mind when they thought of the brand Uber, many consumers answered “unsafe,” “sketchy,” “dangerous,” or “be careful.” By contrast, Lyft was seen as decidedly more “fun” and “friendly.” This was true despite the similarity of the two companies’ rider and driver experiences.

As Uber’s press turned negative, the former copycat, Lyft, was seen as increasingly differentiated. Instead of the bad press hurting both players and ride-sharing in general, consumers who had fully adopted Uber in their travel routine were quick to switch to the kinder and gentler option, Lyft. While Uber was and is still seen as innovative by many, it is taking on the negative characteristics of being “experimental.”

Gender issues also play a role in the comparison of Uber and Lyft brand associations. Some of the negative allegations around Kalanick involved the firm’s female-unfriendly culture. As Uber’s press focused on sexism and arrogance, Lyft’s pink logo (see Figure 15.4) became an inadvertent asset.

Figure 15.4 Lyft and Uber Logos

Lyft is perceived as more playful, more female, and, as a result, for both men and women, more safe. Research conducted at Kellogg showed that females were at least three times more likely to lead with a negative comment when they were asked about Uber than when asked about Lyft. Lyft’s longstanding policy of encouraging tipping, which was initially seen as a negative from a rider standpoint, was now seen as being evidence of friendliness and positivity.

Finally, both brands elicited comments from consumers on the subject of alcohol and partying. Once again, the tone of the comments referencing each brand was starkly different. Uber has more associations with drunk, unruly passengers, and the brand even triggers concerns about potential drunk drivers. On the flip side, the perception of Lyft is that it is a way to get home safely and responsibly after drinking. Lyft has the positive associations of being the responsible and safe “designated driver.”

In this particular case, consumer association data is particularly important to the challenge of managing these brands. Despite continued growth in revenue and ridership, Uber has significant challenges, which become more obvious when brand associations are tracked in consumers’ own words. Meanwhile, Lyft has an opportunity to take advantage of a competitor’s problems and to elevate itself as a preferred alternative.

Assessing Brand Health and Defining Brand-Building Strategies

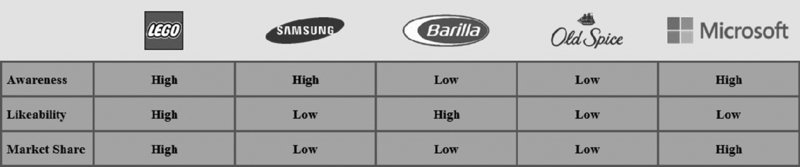

Beyond the simplistic thinking that says that high-awareness brands are strong assets and low-awareness brands are not valuable, we can combine several factors to assess brand health and recommend a path going forward. We create the awareness/liking/market-share model (see Figure 15.5) by combining (1) an unaided awareness measure, (2) data on “liking,” or preference, from brand associations or other measures, and (3) market share or another measure of the brand’s size and financial value.

Figure 15.5 Awareness/Liking/Market Share Model

In the following examples, we will rate different levels of awareness, liking/preference, and market-share status (high or low for each category) to define the classic situations that call for a set of different brand-building strategies, including these five:

- Category or brand expansion. This growth strategy is about taking a strong brand into new spaces. These spaces may be new geographic regions, or new product/service categories, or both.

- Rebranding. Rebranding refers to the stripping of a brand name from a product and giving it new consideration through a new brand name. This growth strategy may be employed when an established brand has so many negative associations that it becomes difficult for potential consumers to see positive features when connected with the current brand name.

- Awareness building. This growth strategy is usually executed through some combination of distribution expansion and advertising spending. It is fundamentally about making sure as many relevant purchasers as possible know about the brand.

- Repositioning. Unlike rebranding, which is about changing a name, repositioning is a growth strategy that is fundamentally about altering the dominant associations that consumers connect with a brand name. Interestingly, the higher a brand’s awareness rating, the more difficult the challenge of repositioning.

- Building relationships. Almost a subset of repositioning, building relationships acknowledges the difficulty of changing consumers’ minds and hearts about well-known, high-awareness brands. Choosing this strategy requires an understanding that changing made-up minds is difficult, and that it is particularly difficult to change consumers’ minds when they sense that you are trying to sell something. Therefore, activity behind this strategy focuses away from the transaction itself, where there is more ability to change consumer perceptions.

Lego (High-High-High): The Case for Brand Extension

A brand with high awareness, high likeability, and strong market share (high-high-high in our model) might seem like a no-problem situation. What could be wrong if everyone knows you, everyone likes you, and everyone buys you? But in fact, brands like this do have challenges, especially if they play in categories that are flat or declining. One of the biggest challenges is that you have no one new to tell about your great product, no one new to convince, and no easy way to grow.

Lego is a classic high-high-high brand, and a dominant player in a shrinking category. Unaided awareness is very high, with Lego freely volunteered as a brand name whether consumers are asked to name brands of toys or brands of children’s blocks. Almost all consumer associations are positive, with the exception of an occasional mention of how painful it is to step on Lego blocks left on the floor. Lego’s share of the block market is dominant. The problem is growth. Lego’s efforts over the past 10 years include a series of attempts to expand through licensing into other categories, including movies, video games, and theme parks. While some of these have been more successful than others, this approach makes strategic sense. Lego has also looked at expansion from the perspective of demographic target markets, by introducing products that appeal to girls as well as boys, and also to bring back adult men who are former Lego players and still Lego lovers.

Samsung (High-Low-Low): The Case for Rebranding

As we build our brand strategy matrix, we look at a situation in which a brand has high awareness, low liking, and low market share. In this case, the brand is well known and recognized, but consumers have negative associations about it. For this reason, most consumers choose other brands in the category. This is a challenge faced by many companies, including Spirit Airlines and Ryanair, Kmart and Sears, and Denny’s and Burger King. In these situations, sometimes negative associations with the brand overwhelm any efforts to design products and services to give consumers a good experience. Many consumers just cannot like anything these brands would offer. In this case, sometimes even the best product development efforts are for naught, until the brand name itself changes. Consumers need a new brand lens to be able to see quality from these providers.

In North America in the 1980s and 1990s, Samsung was a high-low-low brand. Consumers knew it well, but they thought of it as a cheap knockoff of Sony. As such, its market share was not substantial. For this reason, Samsung products were priced substantially below Sony’s as the brand fought to be considered by consumers. But this pricing reinforced beliefs that Samsung was a second-rate brand.

Samsung’s approach to remedy this issue is interesting because of the path it did not take: when it might have undertaken a rebranding, it did not. Samsung had considerable R&D resources and great ability to design good products. But the brand image and Samsung-branded products were not considered high quality. In a situation like this, the brand appears to have value because of its high awareness, but in reality it is not an asset because of the associations tied to the name. This is the classic situation where a firm must consider using a new brand name, with little or no connection with the first.

While rebranding would have been an obvious answer to Samsung’s quality- perception issue, it was a difficult conclusion for Samsung executives to embrace for several reasons. First, these decisions, even for the North American business, were made in South Korea. In Korea, the Samsung brand is strong: it is a very high-awareness, high-liking, high-share asset. In fact, at the time, Samsung was the unofficial national brand of South Korea. Appropriately, Samsung’s brand strategy in Korea was one of category expansion. It had taken the Samsung brand successfully into categories as diverse as shipbuilding, insurance, and hospitals. The executives felt that surely this strong, healthy, and valuable brand would be an asset in the United States, just as it was in South Korea. Further, ceding the Samsung name to Japanese rival Sony in the North American market would have been totally unacceptable.

And so the executives stuck with the Samsung brand, even to the point of avoiding any major sub-brands. Eventually, they were able to chip away at the negative perceptions of Samsung—through the passage of time, through entry to new categories like handsets, and as a result of Sony’s mistakes and troubles. They did not rebrand; instead they took the longer route of repositioning. But it took nearly 30 years to change the image. Contrast this with the renaming of another Korean electronics firm: from Lucky Goldstar to LG. With no link to the past, LG was able to quickly establish positive equity.

This example demonstrates the power of the rebrand option. Building awareness is expensive, to be sure. But changing perceptions, especially on a high-awareness brand, is not only expensive, it is also very, very, slow. The LG strategy and the Samsung strategy were both successful; it just depends whether you need to get the job done in 3 years or 30.

When a high-awareness brand wants to mean something it doesn’t, look for the use of a new moniker. If McDonald’s someday wanted to run a chain of super-healthy fast-food restaurants, it might launch under a name with no link to McDonald’s. When Toyota wanted to play a significant role in luxury automotive, out came the stand-alone brand, Lexus. And, as Facebook’s most committed users became older, the firm focused its youth efforts under a different brand name, Instagram.

Barilla: (Low-High-Low): The Case for Awareness Building

The case of low awareness, high liking, and low share is a clearer, more easily understood problem and solution. Here, most potential targets are unaware of the brand, but those who know it like it a lot. Share is low, but awareness is the clear culprit. In this case, the obvious answer is also the right one: awareness building.

A great example here is Barilla pasta’s entry into the U.S. market. In Italy, Barilla is a dominant, mass brand of pasta, perhaps like Prince or Creamette in the United States. It is solid quality but not perceived as anything special. Looking for a way to grow, the firm began importing to the United States, where the brand was an unknown entity, the classic low-awareness situation. However, it was obvious from the packaging that the brand was from Italy. Therefore, in the United States, the product took on all of the positive associations of the “brand of Italy,” along with perceptions of authenticity and imported quality. The fact that Barilla was more expensive than domestic pasta didn’t hurt. Therefore, though the brand had low awareness, it had high liking among those who saw it. Margins were higher for Barilla than for U.S. brands, and so the brand was given more shelf space by the retailers who stocked it. As it became more visible to consumers, its share rose. Finally, the brand became large enough to afford U.S. advertising, and its managers were smart enough to play on the perceptions of Italian authenticity. Thus, this low-awareness, high-liking, low-share brand became a high-high-high success.

Old Spice (Low-Low-Low): The Case for Repositioning

What do you do if you find yourself in the situation of running a low-awareness, low-liking, and low-market share brand? While this situation might appear to be disheartening, there is a reason to think positively. In fact, the hope in this situation lies in a strange place—the good news is that you have low awareness. Here’s why: in a case like this, most potential consumers do not know the brand name, which is a good thing, because those who do know it have negative perceptions. Both the lack of awareness and negative perceptions contribute to low sales. However, in this case, low awareness is the ticket to a potentially brighter future—it provides the opportunity for potential repositioning.

Unlike rebranding, which involves switching to a new brand identity, repositioning is fundamentally about changing the way consumers think and feel about a brand and creating a more positive set of associations around an already existing equity. This is always a challenge, but as we have discussed before, it is even more of a challenge when awareness is high. The more people know a brand, the more difficult it is to tell them something different from what they already believe about it. This is true particularly with political candidates’ brands—the more well known a candidate is, the less able he or she is to change positions on issues to please an electorate.

When most potential customers don’t know the brand, they become, in a sense, a clean slate where we can start fresh in building positive associations. In fact, when we look at the challenge of repositioning, the greatest success stories often deal not with changing the minds of past customers who have negative perceptions, but with engaging a new group of consumers and building positive associations with this new audience. Sometimes this new audience is a new generation, sometimes it is a new market segment, and sometimes it is in a new country or geographic location. But in all of these cases, marketers are speaking to a fresh target.

A great repositioning example here is the brand Old Spice. When acquired by Procter & Gamble in 1990, this brand was in rough shape. The brand had low awareness and relevancy, especially among young to middle-aged consumers. Among the aware, associations were negative—old men, ships, fish, and the sea—not great associations for a cologne or grooming brand.

As P&G went to work on repositioning and breathing new life into the Old Spice brand, it did many things, including updating product forms, scents, and packaging. But one of the most important things it did was to speak to a new target: both a new generation and a new gender. In “The Man Your Man Could Smell Like,” the most famous of all Old Spice television ads (in fact, the 2011 Grand Effie-winning ad), the brand did just that. The spot starts sonorously with, “Hello ladies. Look at your man. Now back to me. Now back to your man. Now back to me. Sadly, he isn’t me. But if he stopped using lady-scented body wash and switched to Old Spice, he could smell like he’s me.”1 Now Old Spice has a new target—women. And P&G had uncovered a terrifically useful insight: men had started becoming more interested in grooming. The women in their lives were thrilled. However, the men’s first steps often involved borrowing the products and scents of a wife or girlfriend. Here was the brand growth opportunity. Get the “lady” to support her man’s new interest in grooming by purchasing products just for him. Combine a new target with a great consumer insight, and a brand is reborn.

Many of the most successful brand repositionings of this era, including IBM, Stella Artois, and Havaianas, have one strategic aspect in common. Enabled by low overall awareness, the brand managers changed the brand image largely by speaking to a new target. Instead of convincing the old users that they were wrong, they spoke to a new group to breathe life into a brand again. This is the hope of the low-awareness, low-liking, low-share brand.

Microsoft (High-Low-High): The Case for Building Relationships

And now, the last case, and one of the most challenging ones: the high-awareness, low-liking, high-market share brand. In this situation, everyone knows the brand, no one likes the brand, but they buy it anyway. The last time we examined the high-awareness, low-liking combination, the recommendation was to walk away from the brand through rebranding. However, in this situation, that is probably neither advisable nor possible. The brand has far too much financial value. So how do you convince consumers who know a brand well—and are committed nonfans—to think again? It’s not going to be easy, but there is a way.

More brands find themselves in this situation than you would think. Often, these are brands—Microsoft, Commonwealth Edison, and many dominant airlines—whose users feel they have no choice. The brands are well known and have significant negative associations, but consumers buy anyway. Fifteen years ago, Microsoft was in this situation. It was one of the most well-known brands on the planet, but among its top associations in consumers’ minds were “evil” and “monopoly.” Nevertheless, consumers bought PCs anyway, because computers were important, and the risks of buying a non-Windows PC seemed very high. While Microsoft’s image today is hardly beloved, it is far less negative. A look at this transformation will reveal the underpinnings of the interesting “build relationships” strategy.

Once consumers know and dislike a brand, it is hard to change their minds. Ironically, it is most difficult to change their minds when trying to sell something. When someone is selling—whether it’s a candidate trying to get a vote or a salesman trying close a deal—consumers know to suspect the messenger. Therefore, efforts to change the mind of a customer who thinks they know best are best placed away from the act of making a sale. To this end, the softening of the image of Microsoft was greatly helped by the halo from publicity around the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, the founder’s private charitable fundraising arm. Along with the Microsoft associations “evil” and “monopoly” was the association with Bill Gates, the firm’s early leader. In the past 15 years, his efforts have shifted from running the firm to other activities, including an active role in the philanthropic foundation that bears his name. Early efforts of the Gates foundation often involved giving away technology to parts of the world that needed it.

Interestingly, at first this charitable activity was seen through the lens of “evil monopoly” as an extended effort to build Microsoft’s global dominance. However, more recent efforts of the foundation, focused on global health and the eradication of malaria in the world, have had a positive impact on perceptions of the Gates Foundation, Bill Gates himself, and even Microsoft. Note that getting farther from the act of selling a product or service, and farther from self-interest, was crucial to the progress on moving the brand association to be less negative.

The key to the slow work of changing the image of the high-awareness, low-liking, but high-market share brand is more about making friends than driving sales. To change this brand image, we must focus on building quality relationships away from the act of completing a transaction.

Digital Data and the Tracking of Brands

How does the digital world change the world of brand tracking? First, it allows quicker, cheaper, and more continuous execution and analysis of existing brand tracking activity. Firms that have historically checked their brand perceptions on an annual basis often field trackers monthly or weekly, especially during times of change. When a new advertising campaign is launched, when a crisis hits a brand, or when competitors introduce a new product, it is useful to keep continual track of consumer perceptions of your brand. Online tracking mechanisms make information turnaround quicker and cheaper, and they also allow continuous versus periodic tracking. Tracking can be done through quick, online fielding of simple surveys, or by analyzing consumer sentiments on social media sites through algorithms. Here, marketers benefit not only from hearing consumer opinions in their own words, but also by capturing sentiments as consumers communicate with each other instead of being asked for their opinions in a survey.

Second, the digital environment has provided marketers with an entirely new set of metrics, with data collected as consumers interact with a brand online. We can track size of audience, how long individuals spend on our images, and how deeply they connect in our content. The cost-per-click metric counts clicks as a measure of depth of engagement. More broadly, firms measure cost per action when the desired action is something other than clicking—often downloading an app or registering interest by leaving an email address. And finally, firms calculate cost per acquired customer (CAC), measuring the cost of all activities attributed to driving a consumer to actually make a purchase.

Increasingly, we also can learn not only about our buyers, but also about those who don’t buy—consumers who search our categories, investigate our brands, or even place us in a shopping cart, but do not pull the purchase trigger. These hot prospects are in some ways even more useful to identify than the consumers who have already purchased.

In digital environments, the ability to track the activity of consumers and the productivity of our content truly expands. However, this data still begs for interpretation. Whether CAC is high or low, we are challenged to diagnose and explain why. Does lack of customer acquisition stem from an awareness problem? Or are consumers aware of our brand, but just not compelled to buy? If so, why? What do they think and feel, and how should we act to become more compelling? The digital measures are useful, but they do not replace the need to understand how many consumers know us and what they think and feel. Digital measures enhance our decision-making ability, but they must be accompanied by an understanding of awareness and associations.

Summary

Brands are important assets, and so the tracking and measurement of brand health has never been more important. Digital environments make this even more true. It is key to keep a pulse of what users and nonusers think and feel about our brands and to understand these perceptions in an authentic way. As we do so, we must measure consumers’ tendency to think of our brands first, their likelihood to consider them a favorite, and the conversion of these thoughts to purchase. Using all of these factors together, we have discussed the awareness/liking/market-share model for determining brand-growth strategy. Building business through awareness building, advertising, repositioning, category expansion, consumer relationship building, and sometimes by even walking away from a brand name, are all useful tools in the brand steward’s bag of tricks.

Julie Hennessy is a clinical professor of marketing at Kellogg and associate chair of the Marketing Department. She is one of Kellogg’s most recognized teachers, having received more than a dozen teaching awards. She began her career in marketing at General Mills and then spent more than a decade at Kraft Foods. She received her BS from Indiana University and her MBA from Kellogg.