CHAPTER 24

Brand New: Creating a Brand from Scratch

Paul Earle

No new product or service can launch anonymously—even, ironically, the global hacker collective Anonymous. Its cheeky name and iconic Guy Fawkes mask visual identity are as good as any new brand created by a professional, and Anonymous is now famous.

Similarly, Brandless—a new company that purports to be the antihero in a postapocalyptic brand world run amok—is of course itself a brand, and has now trademarked its name in nearly 70 categories.

The truth is that brands are omnipresent and inescapable. They impact everything: not just products and services, but people and places. Brands have impact, and great new ones can quickly take hold. Especially now.

Why now? I believe we are in the early stages of a full-fledged revolution in the consumer sector: within the next five years, practically every category will face radical change brought on by a new brand created from scratch. The big incumbent brands don’t have the cachet and consumer hold that they once did, and marketplace conditions—starting with the rise of e-commerce—are making it easier than ever for upstarts to get a new alternative commercialized.

As I often preach, a superb brand wrapped around an average product will outperform the inverse every time. If you’re interested in creating an instantly resonant and relevant brand that develops relationships with people, secures a real competitive advantage, and ultimately materially improves your company’s financial value, read on.

Four Steps to Creating a Brand that Wins

Here are the four steps to creating a powerful new brand, based on my decades of experience as a practitioner, academician, and writer.

Step 1: Look for a Hook: Finding Sparks

When creating a new brand, it must absolutely be rooted in, well . . . something. You just need some sort of hook, a spark, a way in. Great new brands are never arbitrary.

So what defines the “something” in which a brand must be rooted, and how do you uncover it? My partners and I explore product, story, and purpose.

Product

Deeply ponder the product or service that you’re looking to brand. What is unique about it? What’s special? What’s . . . a little weird, even? Any nuances or eccentricities of the product should be celebrated, not dismissed; this is the magic that can make a difference.

You can deploy what I’ll call the “Altoids convention.” Altoids is the confection that became a sensation in the 1990s when it was touted as “Curiously Strong,” a line that survives to this day. As you consider how to breathe life into your own new product or service, ask yourself, what is curiously strong about it? The answer to this question should spark a great brand idea or two (and if there simply isn’t anything, you have a product problem and had better solve that first).

Story

We’re innately narrative creatures: simply look at the petroglyphs on caves dating back thousands of years. Does your brand have an inspiring story construct? I was part of the team that created a successful new brand called High Noon vodka, inspired directly by a story about people enjoying each other’s company outside, under blue skies; imagining and capturing this moment far preceded landing on the name itself. Founder origin stories are also compelling . . . and even better, real! There is a great new brand of oatmeal called Mush, inspired by the product for sure, but also by a story that goes back to co-founder Ashley Thompson’s childhood and her unusual practice of soaking her breakfast cereal in milk overnight (see Figure 24.1).

Figure 24.1 Oatmeal Brand Mush

Purpose

The principles for which you stand make for great brand sparks, so your brand purpose should be articulated at the beginning of the process, not at the end. Consumers today want brands they can join, not simply buy. You should also consider the timeliness of your brand’s purpose. Nike is an example of a brand that is evergreen but also inextricably linked to the time of its birth. Coming of age in the 1960s and early 1970s, the Nike brand still has not completely lost its counterculture attitude. What is happening right now that moves people’s hearts and minds? The answer might lead to a powerful brand idea.

Step 2: The Name Game: Proving Shakespeare Wrong

In Romeo and Juliet, Shakespeare wrote: “What’s in a name? that which we call a rose / By any other name would smell as sweet.”

The Bard was one heck of a writer, but he was way off on this one. And apparently the big rose companies agree: the international rose grower David Austin, for example, owns over 60 active trademarks (including “Juliet”). And none of its branded roses have names such as “Sewer Gas” or “Donkey Vomit,” for obvious reasons. Do you think those handles would affect your perception of smell and your experience with the rose overall?

Names, of course, matter. Here are some markers for a great name.

Product Relevance

The name should tell a story that directly or at least indirectly ties to the product itself, its reason for being, and consumer needs/wants. A great example is Peloton, the new home exercise equipment company best known for its digitally connected stationary bike. In cycling parlance, a “peloton” is a group of cyclists at the front of the pack. This name is obviously relevant to cycling and leadership, but also speaks to the fact that via the online community, home cyclists are connected to each other—a “virtual pack” (see Figure 24.2).

Figure 24.2 Home Exercise Equipment Brand Peloton

Another great example is the name for New England’s football team: the Patriots, which honors the region’s key role in the American Revolution. You may not like the team or Tom Brady, but it’s a great name. I shake my head when I see new sports franchises pick names that have nothing to do with their home cities. Exhibit A: Las Vegas’s recent selection of “Golden Knights” as the name for its new pro hockey team, pushed through by the owner because he was formerly in the U.S. Army and that was the name of its parachute team. Huh?!? Wouldn’t a moniker such as “Aces” or “Blackjack” be more of a fit, and more engaging?

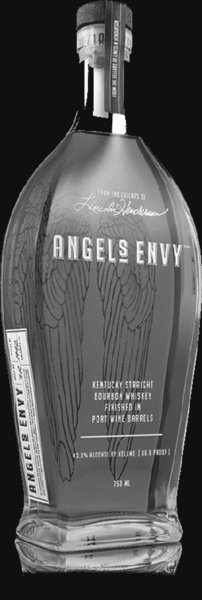

A few years ago, I was part of the team that created Angel’s Envy, a brown spirits brand that was eventually acquired by Bacardi for over $100 million. The name tells a compelling and useful story about the product: our master distiller figured out how to reduce the amount of distillate that would evaporate inside the barrel during aging, making the flavor more intense (the lost spirit is called the “angel’s share,” so we created heavenly envy, of course). The name highlights this innovation and enhanced experience in an interesting and memorable way.

The importance of product and consumer relevance is why I typically don’t care for names that are portmanteaus (new composites of existing words, or elements of words). What the heck is an “Accenture,” and what adds up to “Xfinity”? Again, these brands may work now, but only thanks to massive resources, a lot of time, and frankly, some luck. Of course, there are exceptions. Procter & Gamble’s “Swiffer” is an effective name, and it previously had no meaning at all. And one benefit of portmanteaus is that they can skirt trademark challenges, because by definition the composite word is unlikely to have previously existed.

Emotion

“Form follows function, but both report to emotion,” said Willie Davidson, superstar designer and grandson of the founder of a certain motorcycle company. Emotion is the king of the jungle in marketing and innovation, and it certainly wins in naming. A great name is essentially a short ad for the product, evoking feeling and inspiring some kind of action (consciously or unconsciously). If the name is met with indifference, it is by my definition a lousy name. Even slightly polarizing names are better than those bereft of all feeling (the previously mentioned oatmeal brand “Mush” is a great example; most love the name, but some really hate it. Nobody is indifferent, however, and that means the company is on to something!). The bottom line is that names must engage.

One reason Angel’s Envy is so engaging is that the name is rife with creative tension. “Envy” is one of the seven deadly sins in Roman Catholic theology, and certainly not what you’d expect from a divine figure such as an angel. The feminine associations with “angel” also clash with the overwhelmingly male skew of a bourbon’s consumer base. All this prompts intrigue, discovery, and dialogue—simply from the marriage of two words.

Ease of Use

Generally speaking, names should be as short as possible and roll off the tongue. Brevity is important not just because short names tend to be more memorable, but also because they make it easier for your design team, which has precious limited real estate to work with when creating packaging labels and other elements. Procter & Gamble has mastered the art of short, snappy names: Tide, Gain, Cheer, Scope, Bold, Crest, Joy, and so on. Again, there are exceptions to these unofficial rules. I think a name can be long, provided it is intentionally so and not because of sloppiness. I Can’t Believe It’s Not Butter is an example, as is the great old 1970s brand Gee, Your Hair Smells Terrific.

Regarding the important role of sound in branding, it’s best if your name is mellifluous (mellow or sweet sounding)—or at least not the antithesis. Avoid tongue twisters or names that might be confusing to pronounce. Try saying the name out loud a few times; if it sounds like you’re clearing your throat in the late stages of a cold, it’s time for plan B.

Names that are vaguely feminine are among my favorites, mainly because the abundant use of vowels just makes them nice to say and hear. Some of the great new names today hit this mark: Hello (oral care), Olly (vitamins), and Mio (water enhancers).

Marketability

Identifying a brand name that is inherently marketable reminds me of Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart’s comment on recognizing pornography: that it was impossible to define, but you know it when you see it. However it is defined, marketability is an important consideration in today’s world of hyper-connectedness. Put simply, the idea has to be hardwired for multidimensional engagement from the beginning. Run a few internal tests for what we call “campaignability”: What is a potential tagline? What about a launch act? Or a social campaign? If you find that it feels unnatural to market your name idea, it’s probably not a very good name. In the Angel’s Envy example, we knew early on that playing off the juxtaposition between an angel and a cardinal sin would be a winner in the marketplace.

When I’m deep into a naming dive, my internal name finder is at a very high state of alert practically around the clock. Once I’m “on,” every word I see or hear might be repurposed into a winning name. It might be in print or in online media, on television, in conversation with a Lyft driver, on street signs, or on a bumper sticker. Or it might be on a menu at a restaurant, a lyric of a song on the radio, a paper flyer stapled to a telephone pole, the air safety manual on a 737—anything, anywhere. And if it’s interesting to me, I’ll write it down. Some collect stamps, or coins, or antiques: I collect words.

I have heard lots of chatter about technology-based solutions to name creation, but I’m dubious that naming can be done well without a really intense and really analog, old-fashioned human touch.

Step 3: A Click and a Prayer: Searching the Trademark Office

As with all other functions of the innovation game, an idea that is never implemented has essentially no value. In context: you will need to properly clear your name of all trademark issues if you want to comfortably (and responsibly) use it.

In the United States alone, there are over 400,000 new trademark applications every year. This inventory of potential land mines and roadblocks is massive, and chances are that name you love has already been conceived of by someone else. Anxiety, for me, is that couple of seconds waiting for the return from a search for a name I love on the trademark office web site. Usually, the results are disappointing.

To improve your odds of success, it’s helpful to know how trademark law actually works. With a few exceptions, rights to a mark are specific to a predefined class of goods. For example, the mark “Acme” may be in use in beverages but available in laundry detergent. Where things can get tricky is the standard of “confusingly similar,” which is ultimately a matter of judgment. If there is a valid Acme trademark for beverages and you file for Acme-1 in the same category, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office examiner might argue that your mark would be confusingly similar and refuse it. Even if you did get your application through, the Acme brand owner could still litigate if you persist. In this instance, the plaintiff would probably win.

At their essence, trademarks are indications of source—the roots of this idea go back to the mark or “brand” used to identify cattle. I would argue that, indeed, Acme-1 might confuse consumers into thinking that the product is related to the original Acme. However, you can certainly try altering your trademark through unusual spellings or other forms of modification. For example, Yoplait named its latest yogurt “Plenti,” not the more common “Plenty,” and passed the trademark test.

The strongest rights to a trademark that you can have still come from actually using it. In trademarks, use reigns. A trademark owner can even lose rights to a brand if usage stops; in trademark parlance we often say, “use it or lose it.” If you desire a trademark in a particular category, and you think that a trademark that is blocking you has not been in bona fide use within the past three years, you can actually move to cancel that mark and take it as your own. This happens all the time.

Indeed, much of trademark management is an art, not a science. With a few extreme and obvious exceptions (I would not recommend that you file a trademark application for “Coca-Cola”), practically everything lives in a gray area. You have to be smart and try to find creative work-arounds to problems. Experience and judgment are key (and so is a good trademark lawyer).

Step 4: Say It with Pictures: Developing Brand Design

Once you have your name, you still need to take the final step toward creating your great new brand. You have to animate it—bring life to it—through great design. If done well, design has nearly magical qualities. Design can work at a very powerful psychological level and provide incredible depth and breadth of meaning to an otherwise lifeless word.

Design can be as simple as a logo and preliminary color scheme, or it can be as complex as full packaging concepts. When he was first starting out, my friend Craig Dubitsky was able to generate substantial interest in his Hello oral-care brand with many sophisticated retail buyers simply by using the name and its backstory along with beautifully designed packaging: while he had a smart point of view on formulation, he didn’t even have a finished product yet! (See Figure 24.3.) This interest helped him raise capital and sign up retailers—and the rest is history. When combined with design, names make for very valuable brands, right from the beginning. Design can also be a real asset financially (it is categorized most often under copyrights, one of the four pillars of intellectual property assets).

Figure 24.3 Toothpaste Brand Hello

As an example, the Angel’s Envy design was instantly one of the enterprise’s most important elements (see Figure 24.4). The angel’s wings painted on the back of the bottle took on the illusion of glowing and nearly taking flight when backlit on a bar shelf. This design treatment instantly made the new brand intriguing and engaging. It also helped with investor and customer pitches, long before the first case of bourbon was finished. A well-developed brand design is a great selling tool.

Figure 24.4 Bourbon Brand Angel’s Envy

Summary

Creating a new brand is an incredibly challenging process. It can also be thrilling, should you go all the way from a blank piece of paper to a gleaming, purposeful, beautiful new brand that is out in the world.

It’s a contact sport, for sure. But if you follow the guidance here, you might just find yourself still standing when the whistle blows at the end . . . a winner.

Paul Earle is principal of Earle & Company, an innovation, branding, and design collective, an adjunct lecturer of innovation and entrepreneurship at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, and a monthly contributor to Forbes. He previously served as founder and president of the brand acquirer River West Brands, and executive director of Farmhouse, the innovation center at the global creative agency Leo Burnett. He received his BA from Hamilton College and his MBA from Kellogg.