Chapter Five

Knowledge Building and Deep Learning

THE COVER STORY IN THE BUSINESS SECTION OF THE Toronto Globe and Mail was titled “Knowledge Officer Aims to Spread the Word” (2000a). In its profile of Rod McKay, international chief knowledge officer at KPMG, the article said, “McKay's challenge is to get KPMG's 107,000 employees at all levels worldwide to share information” (p. M1). “Knowledge sharing,” says McKay, “is a core value within KPMG. Every individual is assessed on their willingness to share their experience with others in the firm” (p. M1).

Knowledge building, knowledge sharing, knowledge creation, knowledge management. Is this just another fad? New buzzwords for the twenty-first century? They could easily become so unless we understand the role of knowledge in organizational performance and set up the corresponding mechanisms and practices that make knowledge sharing a cultural value.

Information is machines. Knowledge is people. Information becomes knowledge only when it takes on a “social life” (Brown & Duguid, 2000). By emphasizing the sheer quantity of information, the technocrats have it exactly wrong: if only we can provide greater access to more and more information for more and more individuals, we have it made. Not so! Instead what you get is information glut.

Brown and Duguid (2000) establish the foundation for viewing knowledge as a social phenomenon:

Knowledge lies less in its databases than in its people. (p. 121)

For all information's independence and extent, it is people, in their communities, organizations and institutions, who ultimately decide what it all means and why it matters. (p. 18)

A viable system must embrace not just the technological system, but the social system—the people, organizations, and institutions involved. (p. 60)

Knowledge is something we digest rather than merely hold. It entails the knower's understanding and some degree of commitment (p. 120)

If you remember one thing about information, it is that it only becomes valuable in a social context.

Attending too closely to information overlooks the social context that helps people understand what that information might mean and why it matters. (p. 5)

[E]nvisioned change will not happen or will not be fruitful until people look beyond the simplicities of information and individuals to the complexities of learning, knowledge, judgement, communities, organizations, and institutions. (p. 213)

Incidentally, focusing on information rather than use is why sending individuals and even teams to external training by itself does not work. Leading in a culture of change does not mean placing changed individuals into unchanged environments. Rather, change leaders work on changing the context, helping create new settings conducive to learning and sharing that learning.

Most organizations have invested heavily in technology and possibly training, but hardly at all in knowledge sharing and creation. And when they do attempt to share and use new knowledge, they find it enormously difficult. Take the seemingly obvious notion of sharing best practices within an organization. Identifying the practices usually goes reasonably well, but when it comes to transferring and using the knowledge, the organization often flounders. Hewlett-Packard attempted “to raise quality levels around the globe by identifying and circulating the best practices within the firm” (Brown & Duguid, 2000, p. 123). The effort became so frustrating that it prompted Lew Platt, chairman of HP, to wryly observe, “if only we knew what we know at HP” (cited in Brown & Duguid, p. 123).

In this chapter, we will see several examples of knowledge-creation and sharing from business and education. These organizations and schools are still in the minority, but they are the wave of the future. (And what we can learn from them dovetails perfectly with the discussion in previous chapters.) I will also describe major advances in deep learning that we are making in our multi-country initiative “new pedagogies in deep learning for deep learning” (Fullan, Quinn, & McEachen, 2018).

Examples from Business

In their study of successful Japanese companies, Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) explain that these companies were successful not because of their use of technology but rather because of their skills and expertise at organizational knowledge creation, which the authors define as “the capability of a company as a whole to create new knowledge, disseminate it throughout the organization, and embody it in products, services and systems” (p. 3).

Building on earlier work by Polyani (1983), Nonaka and Takeuchi make the crucial distinction between explicit knowledge (words and numbers that can be communicated in the form of data and information) and tacit knowledge (skills, beliefs, and understanding that are below the level of awareness): “[Japanese companies] recognize that the knowledge expressed in words and numbers represents only the tip of the iceberg. They view knowledge as being primarily ‘tacit’—something not easily visible and expressible. Tacit knowledge is highly personal and hard to formalize, making it difficult to communicate or share with others. Subjective insights, intuitions, and hunches fall into this category of knowledge. Furthermore, tacit knowledge is deeply rooted in an individual's action and experience, as well as in the ideals, values, or emotions that he or she embraces” (p. 8). Successful organizations access tacit knowledge. Their success is found in the intricate interaction inside and outside the organization—interaction that converts tacit knowledge to explicit knowledge on an ongoing basis. My book Nuance makes exactly this point. Effective leaders—and I provide 10 case study examples in Nuance—get below the surface, helping others to do so. They constantly get at knowledge in context where (as we saw in the previous chapter) learning becomes the work.

The process of knowledge creation is no easy task. First, tacit knowledge is by definition hard to get at. Second, the process must sort out and yield quality ideas; not all tacit knowledge is useful. Third, quality ideas must be retained, shared, and used throughout the organization.

As Nonaka and Takeuchi (1995) say,

The sharing of tacit knowledge among multiple individuals with different backgrounds, perspectives, and motivations becomes the critical step for organizational knowledge creation to take place. The individuals' emotions, feelings, and mental models have to be shared to build mutual trust. (p. 85)

In further, more comprehensive work, von Krogh, Ichijo, and Nonaka (2000) subtitle their book “how to unlock the mystery of tacit knowledge and release the power of innovation.” Lamenting the overuse of information technology per se, von Krogh et al. take us on a journey that is none other than an explanation of how effective companies combine care or moral purpose with an understanding of the change process and an emphasis on developing relationships (corresponding, of course, to Chapters 2 through 4 in this book)—again, ideas we delved into in Chapter 4.

Knowledge enabling includes facilitating relationships and conversations as well as sharing local knowledge across an organization or beyond geographic and cultural borders. At a deeper level, however, it relies on a new sense of emotional knowledge and care in the organization, one that highlights how people treat each other and encourages creativity. (von Krogh et al., 2000, p. 4)

Knowledge, as distinct from information, “is closely attached to human emotions, aspirations, hopes, and intention” (von Krogh et al., 2000, p. 30). In other words, there is an explicit and intimate link between knowledge building and internal commitment on the way to making good things happen (see Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1).

I will soon take up the not-so-straightforward chicken- and-egg question of the causal relationship between collaborative work cultures and knowledge sharing, but let's stay for a moment with the conditions under which people share knowledge. Von Krogh et al. elaborate:

Knowledge creation puts particular demands on organizational relationships. In order to share personal knowledge, individuals must rely on others to listen and react to their ideas. Constructive and helpful relations enable people to share their insights and freely discuss their concerns. They also enable micro communities, the origin of knowledge creation in companies, to form and self-organize. Good relationships purge a knowledge-creation process of distrust, fear, and dissatisfaction, and allow organizational members to feel safe enough to explore the unknown territories of new markets, new customers, new products, and new manufacturing technologies. (p. 45)

Von Krogh et al. (2000) emphasize that a culture of care is vital for successful performance, which they define in five dimensions: mutual trust, active empathy, access to help, lenience in judgment, and courage. We have already seen some of these terms in Chapter 4 where we found that cultures in highly effective schools provide both technical and emotional support to system members. Similarly, the US Army, KPMG, Gemini Consulting, Monsanto, British Petroleum, Sears, and a host of other companies in “tough” businesses espouse quality relationships as vital to their success.

Many of us have experienced firsthand the consequences of not attending to these matters. Von Krogh et al. (2000, pp. 56–57) summarize Darrah's study (1993) of a computer components supplier. The company faced severe productivity and quality problems. Management's response was to punish ignorance and lack of expertise among factory-floor workers; at the same time, whenever they ran into manufacturing problems, it explicitly discouraged them from seeking help from the engineers who designed the components and organized the production line. These workers gained individual knowledge as best they could. They worked on sequentially defined manufacturing tasks and tried to come to terms with the task at hand, without thinking through the consequences for the performance of other tasks at other stages of the manufacturing process. When a new worker was employed, he received little training. Yet for productivity and cost reasons, the novice would be put to work as soon as possible. Knowledge transactions between workers and engineers were very rare, and most of the knowledge on the factory floor remained tacit and individual. The tacit quality of individual knowledge was pushed even farther because the foremen would not allow personal notes or drawings to help solve tasks.

Concerned with the severe productivity and quality problems, a new production director suggested a training program for factory workers that would help remedy the situation. The program was designed in a traditional teaching manner: The product and manufacturing engineers were supposed to explain the product design and give an overall view of the manufacturing process and requirements for each step. At the end of the training session, the engineers would ask the workers for their opinions and constructive input—a knowledge transaction intended to improve quality and communication. The workers, however, knew the consequences of expressing ignorance and incompetence, and they did not discuss the problems they experienced, even if they knew those problems resulted from flaws in product design. Nor did they have a legitimate language in which to express their concerns and argue “on the same level” as the engineers. The workers mostly remained silent, the training program did not have the desired effects, and the director left the company shortly thereafter.

What about the causal relationship between good relationships and knowledge sharing? Most people automatically assume that you build relationships first and information will flow. Von Krogh et al. (2000) seem to accept this causal direction: “We believe a broad acceptance of the emotional lives of others is crucial for establishing good working relationships—and good relations, in turn, lead to effective knowledge creation” (p. 51). However, I would venture to say, and again refer to Chapter 4, effective cognitive and emotional support occurs simultaneously. There is no separation of sequence between the two. They feed on each other in a virtuous spiral.

Von Krogh et al. (2000) draw the same conclusion when they talk about two interrelated responsibilities: “From our standpoint, a ‘caring expert’ is an organizational member who reaches her level of personal mastery in tacit and explicit knowledge and understands that she is responsible for sharing the process” (p. 52, emphasis in original).

Figure 5.1 illustrates the elements of knowledge exchange. Knowledge is constantly received and given, as organizations provide opportunity to do so and value and reward individuals as they engage in the receiving and sharing of knowledge. The logic of what we are talking about should be clear: (i) complex, turbulent environments constantly generate messiness and reams of ideas; (ii) interacting individuals are the key to accessing and sorting out these ideas; (iii) individuals will not engage in sharing unless they find it motivating to do so (whether because they feel valued and are valued, because they are getting something in return, or because they want to contribute to a bigger vision).

Figure 5.1. Knowledge-sharing paradigm.

Leaders in a culture of change realize that accessing tacit knowledge is crucial and that such access cannot be mandated. Effective leaders understand the value and role of knowledge creation; they make it a priority and set about establishing and reinforcing habits of knowledge exchange among organizational members. To do this, they must create many mechanisms for people to engage in this new behavior and to learn to value it. Control freaks need not apply: people need elbow room to uncover and sort out best ideas. Leaders must learn to trust the processes they set up, looking for promising patterns and looking to continually refine and identify procedures for maximizing valuable sharing. Knowledge activation, as von Krogh et al. (2000) call it, “is about enabling, not controlling…anyone who wants to be a knowledge activist must give up, at the outset, the idea of controlling knowledge creation” (p. 158). They elaborate:

From an enabling perspective, knowledge that is transferred from other parts of the company should be thought of as a source of inspiration and insights for a local business operation, not a direct order that must be followed. Control of knowledge is local, tied to local recreation…The local unit uses the received knowledge as input to spark its own continuing knowledge-creation process. (p. 213)

It is important to note that companies must name knowledge sharing as a core value and then establish mechanisms and procedures that embody the value in action. Dixon (2000) provides several illustrations. One involves British Petroleum:

British Petroleum's Peer Assist Program. Peer Assist enables a team that is working on a project to call upon another team (or a group of individuals) that has had experience in the same type of task. The teams meet face-to-face for one to three days in order to work through an issue the first team is facing. For example, a team that is drilling in deep water off the coast of Norway can ask for an “assist” from a team that has had experience in deep-water drilling in the gulf of Mexico. As the label implies, “assists” are held between peers, not with supervisors or corporate “helpers.” The idea of Peer Assists was put forward by a corporate task force in late 1994, and BP wisely chose to offer it as a simple idea without specifying rules or lengthy “how-to” steps. It is left up to the team asking for the assistance to specify who it would like to work with, what it wants help on, and at what stage in the project it could use the help. (p. 9)

That was 1994. In 2010, we see the danger of relying on ad hoc success stories when BP was responsible for one of the largest environmental disasters in history as it failed to control an explosion and consequent series of oil leaks in the Gulf of Mexico—the biggest leak in history, discharging some 4.9 million barrels (210 million US gallons) into a massive area, taking several years to control. BP was eventually convicted of gross negligence and reckless conduct and fined $42 billion, not to mention additional lawsuits. Peer-to-peer assistance is a good idea for using lateral knowledge, but it must be governed by an overall system of moral purpose and oversight.

Probably the best-known example of leveraging knowledge within a team is the US Army's use of after-action review (AARs). The AARs are held at the end of any team or unit action with the intent of reusing what has been learned immediately in the next battle or project. These brief meetings are attended by everyone who was engaged in the effort, regardless of rank. The US Army's simple guidelines for conducting AARs are (i) no sugar coating, (ii) discover ground truth, (iii) no thin skins, (iv) take notes, and (v) call it like you see it. The meetings are facilitated by someone in the unit, sometimes the ranking officer, but just as often another member of the team. The learning from these meetings is captured both by the members, who all write and keep personal notes about what they need to do differently, and by the facilitator, who captures on a flip chart or chalkboard what the unit as a whole determines that it needs to do differently in the next engagement. Army AARs have standardized three key questions: What was supposed to happen? What happened? And what accounts for the difference? An AAR may last 15 minutes or an hour, depending on the action that is being discussed, but in any case, it is not a lengthy meeting.

Bechtel's Steam Generator Replacement Group also uses this practice, although it calls the meetings “lessons learned” instead of AARs. Bechtel is a multibillion-dollar international engineering, procurement, and construction company engaged in large-scale projects, such as power plants, petro- chemical facilities, airports, mining facilities, and major infrastructure projects. Unlike other parts of Bechtel in which individuals work in ever-changing project teams, the Steam Generator Replacement Group is a small specialized unit that works on a lot of jobs together. Anything learned on one job can be immediately used by the team on the next job. The nature of its work leaves little room for error. The average window of time to replace a steam generator is 70 days or less, unlike the typical Bechtel project, which may last two years or more. This unforgiving schedule mandates that the Steam Generator Replacement Group learn from its own lessons, because even a small mistake can result in a significant delay to a project. The lessons are captured in two ways: first, in weekly meetings to which supervisors are required to bring lessons learned; then, at the end of each project, the project manager brings all players together for a full day to focus on the lessons learned (pp. 37–40).

The design criteria underlying these examples are crucial:

- They focus on the intended user(s).

- They are parsimonious (no lengthy written statements or meetings).

- They try to get at tacit knowledge (this is why personal interaction or exchange is key and why dissemination of “products” or explicit knowledge by itself is rarely sufficient).

- Learning takes place “in context” with other members of the organization.

- They do not aim for faithful replication or control.

With the advances in technology and artificial intelligence (AI), clearly the role of knowledge has become much more complex and problematic to harness. Two of the leading experts on new technologies are McAfee & Brynjolfsson. In Harnessing the Digital World (2017), they analyze the explosive and interactive development of Machines, Platforms and Crowds. Machines consist of the expansive capabilities of digital creations; platforms involve the organization and distribution of information; and crowds refer to “the startling amount of human knowledge, expertise, and enthusiasm distributed all over the world and now available, and able to be focused online” (p. 14). McAfee and Brynjolfsson suggest that successful enterprises will be those that integrate and leverage the new triadic set (machines, platforms, and crowds) to do things very differently than what we do today. If we don't learn this new way of learning and working, we “will meet the same fate of those that stuck with steam power” (p. 24).

In a similar vein, the start-up specialist Eric Ries says that adaptability is all the more necessary because the environment is awash with radical changes and unpredictability. Ries then comments on his experiences as an entrepreneur in developing and consulting with startups:

I have come to realize in today's organizations—both established and emerging—are missing capabilities that are needed for every organization to thrive on the century ahead: the ability to experiment rapidly with new products and new business models, the ability to empower their most creative people, and the ability to engage again and again in an innovation process—and manage it with rigor and accountability—so that they can unlock new sources of growth and productivity. (p. 3)

The long and the short of the situation, according to McAfee and Brynjolfsson, is there is no reliable playbook for what to do because “there is simply too much change and too much uncertainty at present” (p. 27). They argue that the best way forward is to “predict less, experiment more.” We are back to the culture of change: Build the capacity to change through “external adaptation and internal integration.”

Knowledge and Education

As some people observe, you can get any fact you want from Google. It has become increasingly clear that knowledge utilization is not that simple. Given, students can become whizzes at technology and access to information but still not be very smart when it comes to making insightful observations, let alone taking solid decisions and actions about life.

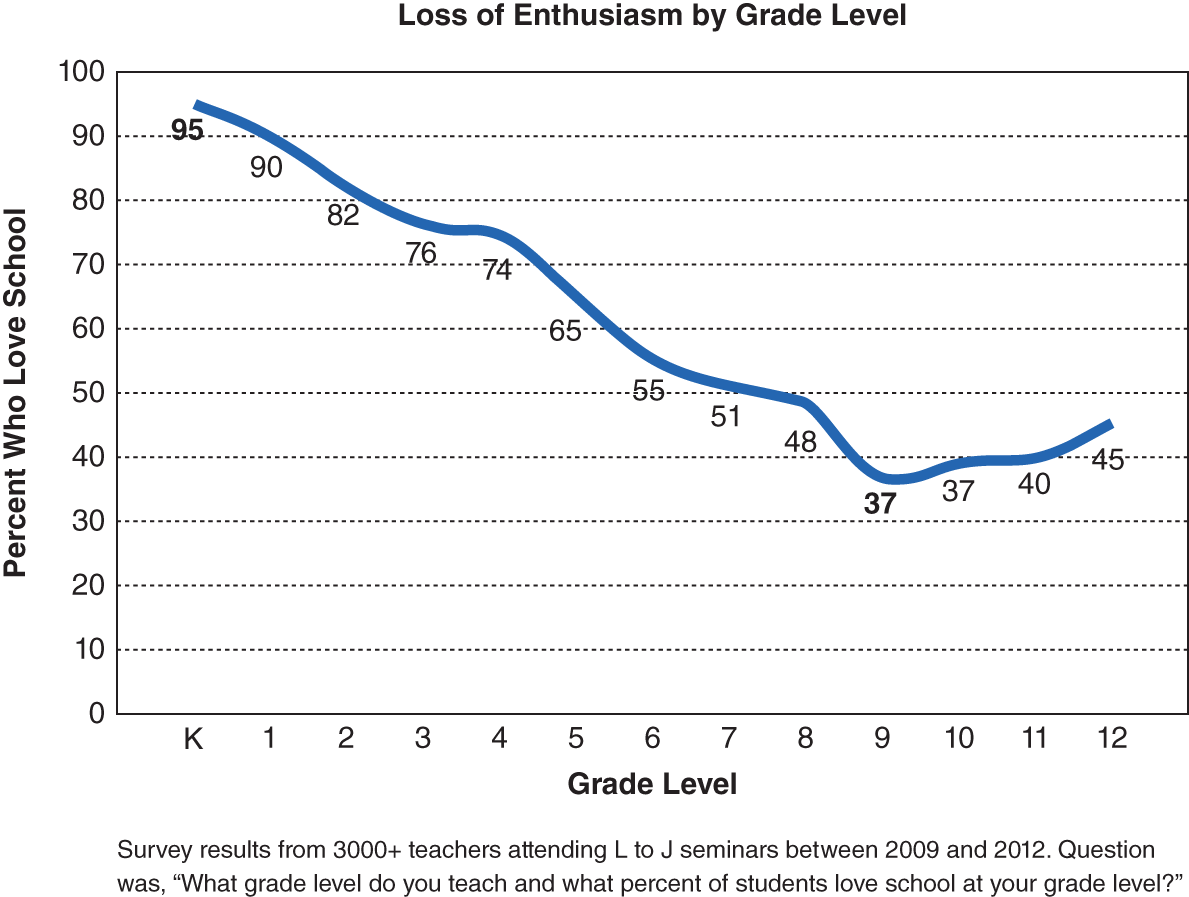

Acquiring sheer knowledge doesn't seem to be the answer. For one thing, students are incredibly bored at the prospect. I referred earlier to the fact that students are less and less engaged as they go up the grades, as the following graph shows. Lee Jenkins asked several thousand teachers at different grade levels “what percentage of your students are enthused about learning.” He found a steady decline from kindergarten to grade 9 where barely more than a third of students found learning worthwhile (Figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2. Loss of enthusiasm (Lee Jenkins, 2012).

In 2014, we decided to act on the knowledge that the present system wasn't working spurred on by the interest of some schools and district or system leaders that wanted to change the public education. We formed a global partnership we called “new pedagogies for deep learning.” We had a framework for action that guided the work and intended the “product” would come from the partnership. We started with the 6Cs, called the “global competencies”:

- Character—Proactive stance toward life and learning to learn, grit, tenacity, perseverance and resilience, empathy, compassion, and integrity in action.

- Citizenship—A global perspective, commitment to human equity and well-being through empathy and compassion for diverse values and worldviews, genuine interest in human and environmental sustainability, solving ambiguous and complex problems in the real world to benefit citizens.

- Collaboration—Working interdependently as a team; interpersonal and team-related skills; social, emotional, and intercultural skills; managing team dynamics and challenges.

- Communication—Communication designed for audience and impact, message advocates a purpose and makes an impact, reflection to further develop and improve communication, voice and identity expressed to advance humanity.

- Creativity—Economic and social entrepreneurialism, asking the right inquiry questions, pursuing and expressing novel ideas and solutions, leadership to turn ideas into action.

- Critical thinking—Evaluating information and arguments, making connections, and identifying patterns, meaningful knowledge construction, experimenting, reflecting, and taking action on ideas in the real world.

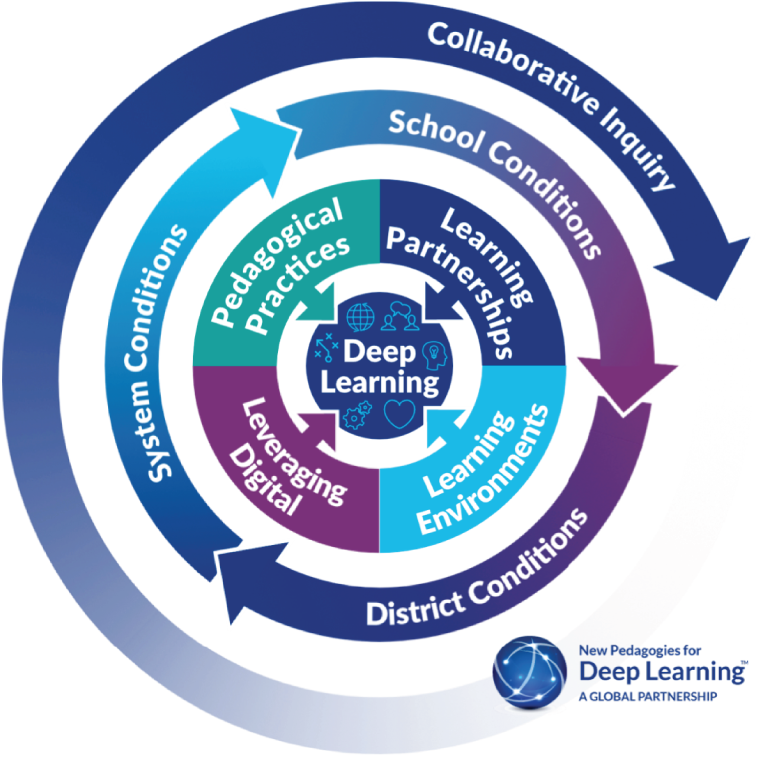

Over the past five years we have worked with over 1,200 schools in eight countries or regions (subsets of schools worked with us, some sponsored by the government, but most coming from clusters and the regional or local levels: Australia, Canada, Finland, Hong Kong Netherlands, New Zealand, Uruguay, and United States). The full model is simple and complex at the same time (Figure 5.3).

Figure 5.3. Deep learning.

We have already seen the 6 Cs that are the center of Figure 5.3 labeled as deep learning. In turn, the Cs are guided by a four-part learning model (partnerships, pedagogical practices, learning environment, and leveraging digital), and supported by organizational and system conditions (school, region, state). All 13 of these components (6 Cs, 4 learning supports, and 3 system supports) have detailed rubrics enabling the use or application of the elements. Schools are supported on an ongoing basis by local cluster leaders with whom our central team works. The result has been thousands of learning examples from schools of the model in action (see also Quinn, McEachen, Fullan, Gardner, & Drummy, 2020).

Let's take two examples out of literally 1,000 or more I could select. The first, from Australia, is called “Young Minds of the Future,” where three elementary schools worked together for three years “to develop ideas that would benefit the world.” The second is a school-district-wide deep-learning endeavor in Avon Maitland District School Board (AMDSB) in Western Ontario that helped engage disconnected students in meaningful learning.

Our video, Young Minds of the Future clearly shows the enthusiasm and crystal-clear articulation (what we call the capacity to “talk the walk”) by students of what they are doing, why, and with what results (for the video see http://www.npdl.global).

In Ontario, Canada we pick up the story of Gabe (pseudonym).

Gabe is part of our working hypothesis that “deep learning” is valuable for all students but is especially effective with students who have been previously disconnected from school and from learning. There are several key points to be made about our deep learning initiative. First, it dramatically caught the interest of students and teachers and those who worked with them. It caused new energy for learning, covered the basics of literacy and math, and created countless “applied” projects. Second (again, us learning from the field), we labeled the work “Engage the World, Change the World,” essentially discovering that once they got going, most students wanted to work on some aspect of a local or global issue, learn about it in teams, and draw conclusions that reflect deep understanding and an aptitude for improvement.

We ended up defining deep learning as having these characteristics:

- Learning that sticks with you the rest of your life

- Learning that connects with passion

- Learning that is team related

- Learning that has significance for the world

- Learning that involves higher-order skills

We also identified what we ended up calling “emergent discoveries” that included the following themes:

- Helping humanity.

- Life and learning merge.

- Students are change agents.

- Working with others is an intense motivator.

- Character, citizenship, and creativity are catalytic Cs.

- Attack equity with deep learning.

We are learning some other things about how to lead in a culture of change (for more detail on the above, see Fullan et al., 2018). How, for example, do you change a stodgy system (boring schooling) into a new enterprise? Part of the answer is to identify a problem and provide the direction of a solution with accompanying supports. We also wondered how much support would be needed to be effective. We developed “tools” in the form of rubrics to guide the key elements of the model. It turned out that these were essential. Participants told us “the tools help us focus” without suffocating local initiative. We have just taken a step to move this forward with another publication, called Dive into Deep Learning: Tools for Engagement (Quinn et al., 2020).

Part and parcel of all this, as you will have surmised, is that the role of teachers and students relative to each other and to knowledge has radically changed closer to the worlds that McAfee, Brynjolfsson, and Ries portrayed (“predict less, experiment more”).

For teachers, we see in Table 5.1 that the knowledge role is squarely as partners being “activators, culture builders, and collaborators.”

These radical alterations in learning, especially in the role of knowledge relative to the roles of students and teachers, have been corroborated in a thorough study of deep learning by Jal Mehta and Sarah Fine (2019). First, despite following promising leads, Mehta and Fine found disappointingly few examples of deep learning in US high schools. This mainly confirms that the knowledge revolution has not infiltrated into the cultures of schools.

Table 5.1. A New Role for Teachers

| Activator | Culture builder | Collaborator |

| Establish challenging learning goals, success criteria, and deep learning tasks that create and use knowledge. | Establish norms of trust and risk-taking that foster innovation and creativity. | Connect meaningfully with students, family, and community. |

| Access a repertoire of pedagogical practices to meet varying needs and contexts. | Build on student interests and needs. Engage student voice and agency as co-designers of the learning. |

Engage with colleagues in designing and assessing the process of deep learning using collaborative inquiry. |

| Provide effective feedback to activate next level of learning. | Cultivate learning environments that support students to persevere, to exercise self-control, and to feel they belong. | Build and share knowledge of the new pedagogies and the ways they impact learning. |

Digging deeper (no pun intended), Mehta and Fine did discover examples of deep learning. Some of these were at what the authors call “the periphery”—in after-hours programs, theater clubs, and sports. A few instances were found in the odd classroom. In these cases, we see that the new role of knowledge is very different in terms of its nature and the roles of teacher and the student, respectively (Table 5.2).

Now we see a more dynamic role of students as creators and investigators of knowledge, passionately pursuing their interests with teachers as enablers and collaborators. Whether any of the above represents the beginning of a new cultural revolution in education remains to be seen. If it does, its success will require all of the ideas in leading cultures of change that I have been amassing in this book.

Table 5.2. Differences in Teaching Practice

Note. Mehta and Fine (2019, p. 351).

| Traditional teachers | Deep-learning teachers |

| Knowledge as certain | Knowledge as uncertain |

| Cover the material | Do the work of the field or domain |

| Student as receiver of knowledge | Student as creator of knowledge |

| Ethos of compliance | Ethos of rigor and joy |

Conclusion

Using education as the focus, the point of all this is that guided deep learning greatly increases the relevance of schooling; it galvanizes students into studying and action. It integrates moral purpose, relationships, and detailed learning. It provides a frame of learning that is good for all students but is especially good for those students who are disaffected from regular schooling (which turns out to be a higher percentage than Jenkins found, as more and more students find that the desperate race for grades is alienating). It finds common ground between education and business and education. It prepares students for the future that turns out to be now, not tomorrow.

In short, this foray into deep learning epitomizes a great deal of what is crucial about knowledge seeking, and what it is like to lead in a world where there is a glut of information, and a massive challenge to make sense of it for learning, and for the world at large. The changes are radical and relentless, and are of a different character than we have seen before. They are unpredictable. They are dangerous, played out in a troubled world. Knowledge is deeper, more dynamic, and in the service of transformation, not just improvement. Success will depend on more of us figuring out how to master the themes in this book.

I now turn to one of the most powerful needs in our framework: how to increase our capacity for coherence making—a theme that we have worked on diligently for the past decade.