Chapter Seven

Leadership for Change

IN AESOP'S FABLE, THE TORTOISE AND THE HARE, THE hare is quick, clever, high on hubris, and a loser. The tortoise is slow and purposeful; it adapts to the terrain and is a winner. The lesson is very close to my own adage: “Go slow to go fast.” The beginning is very important. Going fast can miss context and fail to connect people to their issues and their potential. Too quick and you miss vital learning. Just right and you create accelerating momentum.

There is a difference in my model since the leaders are not exactly tortoise-like. In given change situations, if you lead effectively (as in a culture of change), you gain momentum as you go because more and more people are on board, and they have great specificity and shared coherence. Go slow to go fast, as we call it. I do believe that we can accomplish greater change in shorter periods of time if we understand what it means to lead in a culture of change. Thus, we need to dig deeper into what effective leadership looks like in these complex times.

In this chapter, I begin with the observation that overall, leadership is a mess, not at all up to the challenge of leading effectively in a culture of dynamic and complex change. Then I turn to a threefold framework: appointing leaders; learning as you go; and leaving a legacy.

Leadership Is a Mess

We can start with the widespread finding that almost two-thirds of employees on the average are not actively engaged in their organizations (see Chapter 2). This applies to teachers and students as well as members of most organizations. It is slightly unfair to call this a “leadership problem” but it is. If not the fault of individual leaders, it is the failure of organizations to position leadership effectively. It is accurate to conclude that leadership has not yet found its niche in leading dynamic complex systems.

Recall from the Gallup review in Chapter 2 that the single biggest factor in the performance of individuals and teams is the quality of management. The problem starts with the hiring and appointment of leaders. Peter Cappelli (2019) from the Wharton School in Philadelphia completed a review and titled his report “Your Approach to Hiring Is All Wrong.” He found only a third of companies check whether their recruitment process produces good employees. There is now a tendency to hire from outside. Up until the 1970s, 90% of leadership vacancies came from inside the company. Today, according to Cappelli, barely a third hire from within. Outside hiring has more unknowns—at least in terms of how organizations go about it. It is often outsourced to headhunters; it depends too much on interviews that are notoriously open to bias; it doesn't get at past performance; and it takes longer for outsiders to get up to speed. Selection techniques, concludes Cappelli, “are a bit of a mess.”

We also saw in Chapter 1 Chamorro-Premuzic's (2019) findings that 75% of workers who quit their job do so because of their direct line manager (p. 1). He concludes that “most leaders are bad” and that we overvalue “confidence and assertiveness” (p. 12). He also makes the case for hiring more women, which is another matter. The point is that we often appoint leaders for superficial reasons because they look and sound good, not necessarily whether they can do good.

I did a small, informal test in June 2019 via my Twitter account, where I have 51,000 followers. This is by no means a scientific study (for one thing people who have bad bosses would be unlikely to say so on Twitter). My questions was, “What percentage of leaders are good as in focusing the agenda, working alongside others to get results, and having a positive impact on the organizations?” Incidentally, I think it is difficult under conditions of growing complexity to be this effective. But that is the point. We need especially good leaders to lead cultures of change, and if anything we are not being careful in the recruitment and cultivation of leaders.

Personally, I had predicted that around 20% of leaders would be considered to be highly effective. Within a week, I received 136 replies. Here are some of them:

- 20%, being optimistic.

- 10%—so sad.

- 90% mean well; only 45% truly engage the group.

- In my 20 years of teaching: 1 in 20.

- Less than 10%; the rest think they are—just ask them.

- 95% best intentions; but would guess it is really about 25%.

- At best 7%. The rest are maintaining the status quo with only incremental changes and calling them innovations.

- It doesn't look good—20%. Keep in mind it's a tough gig.

- 30% with a crisis brewing.

The modal response was in the 5–30% range; a handful of responders estimated 65% or so.

Speaking of Twitter, my good colleague Terry Grier, who was the brilliant superintendent of the large, complex, and successful Houston Independent School District, had this to say on June 16, 2019. I think he was lamenting that there were too many bad choices when he offered:

When selecting leaders, how do you identify ‘the real deal’? Ask additional questions tied to your organizational goals; ask probing questions to people NOT listed as references; and monitor once hired; replace a bad hire as quickly as possible—don't wait until year's end!

All and all, my point is not just that there are bad or ineffective leaders, but more that leading in a culture of change is more complex than recognized. To put it another way, leading in systems of growing complexity requires another level of leadership than was hitherto required.

In the rest of this chapter, I first examine the new complexity of leadership including my newest findings about Nuance. I then conclude with what it takes to become highly effective, that is, how do the best leaders actually get that good.

Lessons for Leading in a Culture of Change

There is no question that the environment is changing at an accelerating rate. Under these conditions, it is understandable that some leaders want to match speed with speed. If you go fast and it is superficial, you end up spinning your wheels. Typically, people get left behind. What looks like fast change is an illusion. It feels hectic, but there is little substance.

Change has changed. It is more dynamic with many more opportunities—to fail as well as to succeed. If I distill the lessons in this book, they come down to saying that leadership needs to change because the situation has changed in irreversible ways. Essentially, leadership must become less linear without losing focus.

Heifetz and Linsky (2017) capture the nature of this new leadership work as they expand on the difference between “technical and adaptive work.” Technical change is when the problem is straightforward and requires the use of existing knowledge to address it. In this case, people look to proven experts to solve the problem. The authors then say that almost all of our problems (and they are growing in number and difficulty) require “adaptive solutions.”

The leadership challenge is very different for adaptive problems as they express:

For transformative change to be sustainable it not only has to take root in its own culture, but also has to successfully engage its changing environment. It must be adaptive to both internal and external realities. Therefore, leadership needs to start by listening and learning, finding out where people are, valuing what is best in what they already know, and do, and build from there. (Heifetz & Linsky, 2017, p. xiv)

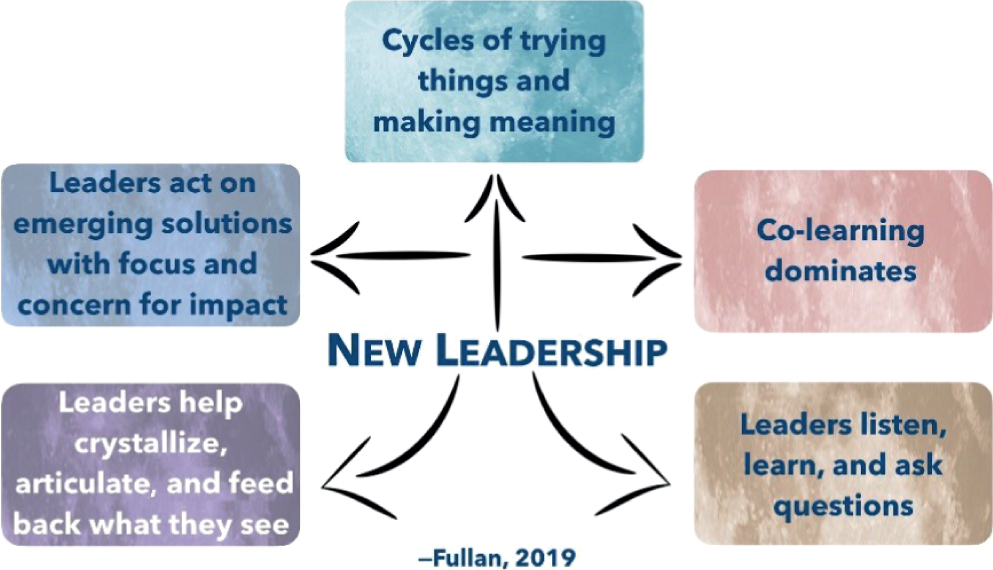

To continue with the spirit of this new leadership, I reproduce in Figure 7.1 a diagram we use in workshops when we are training people in the new leadership.

One can readily see how this sequence of learning and development maps onto Heifetz and Linsky's conclusions about the need for adaptive (but nonetheless focused) leadership.

Let's also examine the new leadership as a list of traits or characteristics as in Figure 7.2.

Figure 7.1. New leadership.

Figure 7.2. Leadership for change.

I turn first to my new study of “nuanced” leaders (who are essentially like those depicted in Figure 7.1).You may recall Marie-Claire Bretherton from Chapter 2, who was appointed as the new principalship of an absolutely terrible school in northern England that had been stuck near the bottom of performance for a decade. It was obvious “what” needed to be changed, but not “how.” Instead of jumping into changes right away, Marie-Claire did two things. She interviewed all staff from cleaners to deputy head. Then she and her assistant, Sam, went on a learning mission.

Myself and Sam had a policy. For the first 8 weeks we would not give any feedback. We literally went on a mission to find anything that we could possibly observe that was good. (Fullan, 2019, p. 17)

Within 18 months the school went from being a failing disaster to winning an award for school of the year—a clear example of go slow to go fast.

Similarly, how could John Malloy go about making progress in the Toronto District School Board (TDSB) with its 583 schools when he was appointed director in January 2016. He talks about the starting point: “I inherited a culture that when you talk about system direction, people then start expecting the templates, the recipes and the roadmaps” (Fullan, 2019, p. 51).

John then restructured the local subsystem to create 28 clusters of 20 schools each (compared to the previous 20 clusters of 30 schools). He then set up a system where he accompanied his 28 area superintendents on school visits throughout the year in order to learn more about the schools and what they might need, and notably to model with the area superintendents what lead learners should do on a daily basis. John, too, was a leader and learner from day one.

In both cases, Bretherton and Malloy were lead learners from the get-go. They were trying to make meaning in the system. At the beginning they had more questions than answers, then they learned more and more. Time and again in cases of success we see leaders “participate as learners” with teachers, principals, and others as they move schools and the system forward.

Such leaders blend and integrate qualities 1 and 2 in Figure 7.2. They are role models for their systems. They learn deeply about the culture and the people through such immersion. At first they have more questions than answers. They listen and listen and then they learn and learn. Before long they learn things perhaps more than others in the system as they cut across the schools. Their questions and suggestions become more informed.

I thank my colleague Roger Martin and fellow researcher Sally Osberg for our third revelation in Figure 7.2. In their study of social entrepreneurship in developing countries where the worlds of the expert and the roles of those living in the situation were vastly different, Martin and Osberg (2015) found that both groups were sources of expertise, knowledge, and insights.

Expert knowledge in a given domain is only one part of the solution, note Martin and Osberg. Effective leaders learn to draw on the wisdom of those not seen or classified as “experts.” Leaders need to position themselves “to absorb lessons from ecosystem actors, especially those disadvantaged by the existing equilibrium” (p. 92). Leaders in a culture of change are not afraid to display their knowledge about things they know (even then they are ready to learn), but they are also hungry to learn when it comes to areas about which they are less knowledgeable. I learned this as well about nuanced leaders. They were relentlessly committed to solving problems, but they were also humble when it came to things they did not know.

Fourth, we have encountered several times in this book the new finding (it should have been obvious) that lead learners always become knowledgeable about the context in which they work. My colleague and fellow consultant, Brendan Spillane, defines nuance as “action informed by deep contextual literacy” (personal communication). All if the elements in Figure 7.2 feed into this notion.

A corollary of “learn in context” is another new finding. Every time you go to a new context, such as change jobs as a leader, you automatically become deskilled in relation to new context. Acting in the manner of expert and apprentice in a new situation is a winning combination. Of course you learn more each time so it accumulates. I would venture to say, given our discussion of ineffective leadership in Chapter 1, that many a leader does not learn deeply within their own cultures even though they may have been on the job for a decade or more. It is all about fashioning yourself as a learner, but also not being afraid to be assertive when the situation calls for it. If it is clear that you are a learner, people will welcome your decisiveness when it is needed.

Fifth, making your moral compass dynamic or active means that your moral values and commitments must be evident to all. Remember the LRN study in Chapter 1 that observable moral purpose on the part of senior management was absent in the eyes of most employees. The consequence:

When CEOs do not consistently behave as moral leaders, 89% of managers under them fail to lead with moral authority. (LRN, 2019, p. 5)

Recall that moral leadership was based on letting purpose lead, inspiring others, animating values and virtues, and building and keeping the moral agenda front and center.

The sixth and final attribute is revealing. Basically, it says that your job as a leader is to spend six or seven years or so developing a collaborative culture of leadership to the point where you become “dispensable.” If you don't leave a legacy culture of the kind we have been discussing in this book you will have failed as a leader. When you do all the things in Figure 7.2 you are de facto a mentor for your organization. You can do other things such as being more aware of and attentive to the kind of human and social talent needed in the organization, establish formal mentoring programs, promote the culture we have been discussing in this book, and being more proactive and explicit about the culture you are cultivating with others.

How Do Highly Effective Leaders Become So Good?

In this book we have examined the five main dimensions of leading in a culture of change: moral purpose, understanding change, relationships, knowledge creation and use, and coherence making. We saw that ineffective leaders often have high degrees of confidence and assertiveness. The deeper aspects of effective leadership require the would-be leader to put in the time to learn them as he or she gets better and better each step of the way. The good news is that good leadership accelerates because by definition you are learning daily.

To capture the nature and spirit of getting better at complex endeavors, I turn to Anders Ericsson, the researcher that Malcolm Gladwell made famous by citing the 10,000-hour rule that states that anybody can become an expert if they put in the 10,000 hours of practice. Ericsson and Pool (2016) wrote the definitive book partly to set the record straight. It turns out that what makes the difference is 10,000 hours of cumulative deliberate practice.

Long a tenet of our approach, this is the idea that you get better at something by doing the work itself with a purposeful practice mindset. Ericsson says that such practice has four characteristics:

- It has well-defined, specific goals.

- It is focused.

- It involves feedback.

- It requires getting out of one's comfort zone (Ericsson & Pool, pp. 15–17).

For leadership Ericsson notes, “Our starting point is the measurement of performance in the real world” (personal communication, April 2016).

In every case of expert performance, leaders become much better at what Ericsson calls “mental representations” of the situation at hand. The good news is that almost all of us can get better over time through deliberate practice:

The main thing that sets experts apart from the rest of us is that their years if experience have changed the neural circuitry in the brain to produce highly specialized mental representations, which in turn makes possible the incredible memory pattern recognition, problem solving, and other sorts of advanced abilities needed to excel in their particular specialties. (p. 46)

If we examine two of our most accomplished “nuanced” leaders—Marie-Clare Bretherton and John Malloy—you will see the development of this expertise at work (Fullan, 2019). They both have a strong sense of moral direction. They are committed to making a difference. But at the early stages they did not know “how” to do this. They saw it as essential that they needed to figure it out by getting inside the problem as a learner. They were willing to get outside their comfort zones. They become clearer and more committed through the work.

After a while, they developed greater insights. It seems that their sense of intuition increased. I would say that this was not because they were born with greater intuition but, rather, that increased intuition is derived from their experiences of taking on more difficult challenges (outside their comfort zones, to quote Ericsson).

All of this is very much compatible with the discoveries about nuance. Nuance leaders immerse themselves in context because they know that context is crucial. They build relationships and get insights with the people they are leading. Each new context, as I said before, to a certain extent “de-skills leaders”—because you need to learn the details and nuances of the new context in order to be effective in it. But it gets easier as you go from context to context for two reasons. First, you know that becoming context-literate is essential so you become oriented and committed to learning about each new context. Second, you start to recognize patterns, and therefore you see patterns more readily.

Nuance revealed another insight about one of the most elusive concepts in leadership, namely courage. Observers of leadership have always touted “courage” but it came across as you either have it or not. Now we see something more subtle. Our effective leaders certainly have a strong moral compass. Then, through attempting more and more and being successful, they actually become more courageous. Marie-Claire Bretherton put it this way: “I think I have probably underestimated in the past the power of your own sense of vision and hope, and your own mental discipline, and your own belief” (Fullan, 2019, p. 41).

This conclusion about the role of courage in leadership—it is a product of action (and then becomes a greater force in its own right)—is corroborated by Povey and McInerney's (2019) book, The Leadership Factor. They identify six Cs as leadership factors: curiosity, changeability, charisma, connection, collaboration, and courage (mostly these are compatible with what I have been saying, although “charisma” would be questionable in my model). Povey and McInerney conclude that “courage” develops as a result of working on the other six factors. The “how” of developing courage is to immerse oneself with others in trying to change something significant, using the skills that I have been addressing in this book, and becoming more courageous as a result of your experiences, skill development, and accomplishments. As I concluded in Nuance, such leaders become courageously and relentlessly committed to a better future. They maintain their humility and empathy, but are passionately loyal to achieving with others a better future that improves humanity (Fullan, 2019, p. 112).

Nuanced leaders—leaders in a culture of change—see the bigger picture; they don't panic when things go wrong in the early stages of a major change initiative. It is not so much that they take their time, but rather that they know it takes time for things to gel. In a sense, they establish the conditions for change and become increasingly persistent about progress.

All through this book the message has been that organizations transform when they can establish mechanisms for learning in the dailiness of organizational life. As Elmore (2000) stated:

People make … fundamental transitions by having many opportunities to be exposed to ideas, to argue them to their own normative belief systems, to practice the behaviors that go with those values, to observe others practicing those behaviors, and, most importantly, to be successful at practicing in the presence of others (that is, to be seen to be successful). In the panoply of rewards and sanctions that attach to accountability systems, the most powerful incentives reside in the face-to-face relationships among people in the organization, not in external systems. (p. 31)

When Henry Mintzberg was asked what organizations have to do to ensure success over the next 10 years, he responded:

They've got to build a strong core of people who really care about the place and who have ideas. Those ideas have to flow freely and easily through the organization. It's not a question of riding in with a great new chief executive on a great white horse. Because as soon as that person rides out, the whole thing collapses unless somebody can do it again. So it's a question of building strong institutions, not creating heroic leaders. Heroic leaders get in the way of strong institutions. (quoted in Bernhut, 2000, p. 23)

Strong institutions have many leaders at all levels. Those in a position to be leaders of leaders, such as the CEO, know that they do not run the place. They know that they are cultivating leadership in others, and they realize that they are doing more than planning for their own succession—that if they “lead right,” the organization will outgrow them. Thus, the ultimate leadership contribution is to develop leaders in the organization who can move the organization even further after they have left (see Lewin & Regine, 2000, p. 220).

I feel compelled to argue again that the main message of this book is not to develop better individual leaders. Rather, the key point is to develop and foster better leadership cultures. We know that this is going to be enormously difficult for two reasons. The first is that the incentives seem to favor hiring what appear to be confident, articulate individuals—what Chamorro-Premuzic (2019) called “confidence disguised as competence” (Chapter 2). We can't get there (leadership cultures) from here (hiring overconfident individuals).

There is certainly a bias in the literature favoring human capital, or individual heroism—a problem recently stressed by Jonathan Aldred (2019) in a new book titled Licence to Be Bad: How Economics Corrupted Us. Economists, argues Aldred, take a narrow view of humans as selfish creatures. Alfred likely overstates the case, but even if humans are not as self-centered calculators as he claims, he is likely right that we do not have enough social learning and collective efficacy in our institutions. I also referred in Chapter 4 to the $575 million multiyear effort undertaken by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation to increase (individual) teacher effectiveness, which failed to make a difference because it focused mainly on the individual teacher (Stecher et al., 2018).

The good news in “leading in a culture of change” is that people rise to the occasion when they are helped by leaders who develop others to do something that is individually and collectively worthwhile. Such leaders tap into fundamental virtues of humans—and when they do, improvement happens quickly.

One of the main conclusions I have drawn is that the requirements of knowledge societies bring education and business leadership closer than they have ever been before. Corporations need souls and schools need minds (of course they need both) if the knowledge society is to survive—sustainability demands it. New mutual respect and partnerships between the corporate and education worlds are needed, especially concerning leadership development. Such endeavors must be based on and guided by the forces discussed in Chapters 2 through 6.

Recent conclusions by evolutionary biologists have placed new more dramatic spotlights on the crucial state of human and moral purpose as we complete the first fifth of the twenty-first century. There is little doubt that the world is becoming more troubled: climate change, unknown future of jobs and the economy; dramatically increasing inequity across the world (the discrepancy between the haves and the have nots), increased stress and anxiety across all groups, unintended consequences of technology including more impersonal connections, decrease in trust, and ultimately threats to global social cohesion.

What do the evolutionary biologist have to say about the trends? I referred to this earlier. The argument is complex, but not difficult to amass (see especially Wilson, 2014; Wilson, 2019, and neuroscientist, Antonio Damasio, 2018, p. 2). Here are some of the key conclusions:

- Humans are not intrinsically good. Each of us is conflicted; sometimes selfish, other times committing to others and the common good (only sociopaths—1% or so of the population—are oblivious to good).

- We are social beings (born to connect). “The inherited propensities to communicate, recognize and evaluate, bond cooperate, compete, and from all these, the deep warm pleasure of belonging to our own special group” (Edward, O. Wilson, p. 75). BUT, this can just as easily take the form of “tribalism”—my group good; all others bad or irrelevant.

- Goodness can evolve. Building on (2), David Sloan Wilson states: “Modern evolutionary theory tells us that goodness can evolve, but only when special conditions are met. That's why we must become wise managers of evolutionary processes. Otherwise evolution takes us where we don't want to go” (pp. 13–14).

- We are a population of groups. “This means that an evolving population is not just a population of individuals, but also a population of groups. If individuals vary in their propensity for good and evil, then this variation will exist at two levels: variation among individuals within groups, and variation among groups within the entire population” (David Sloan Wilson, p. 77).

- Forming harmonious groups is becoming more challenging. Damasio argues that in simpler times, things turned out well because our instincts to form groups and to achieve levels of harmony eventually prevailed. Now, says Damasio, given our more complex evolution and the troubling challenges we face, things may become radically different: “To expect spontaneous homeostatic harmony from large and cacophonous human collectives is to expect the unlikely” (p. 219, italics in original).

These potential developments raise moral purpose to a whole new level—the survival of humankind and the planet itself! We already know that engagement and satisfaction with work and life is on the wane in most organizations, businesses, or schools alike. Now we have one more compelling reason to pay heed—survival itself. But there is more than this. Leading in a culture of change is about fulfillment and flourishing.

When you strip away all the layers, “leading in a culture of change” is about human fulfillment. Why are we on this earth? There is no answer really, but the notion of creating things individually and collectively beyond our imagination, and then some—let's call it the Leonardo da Vinci factor—is not a bad aspiration. This is where Edward O. Wilson ends up going. His solution is to combine a greater respect for the mysteries and ideas within evolutionary biology with the creative freedom of the humanities: “The creative arts for their part continued to flower with brilliant and idiosyncratic expressions of the human imagination” (p. 39).

We can ground this even more. Yes, worry about survival. And at the same time, develop the profound strengths of our fivefold solution: pursue moral purpose, understand change dynamics, establish multiple focused relationships, probe the depths of knowledge creation, and work on the dynamics of coherence-making.

Conclusion

Within all of this is the realization that business, education, governments, and the variety of other agencies have something in common: the moral purpose of living in a dynamic, exciting, and admittedly dangerous world.

The closeness of business and education entities has been further reinforced by our work on “Deep Learning.” The focus on the 6Cs (character, citizenship, collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking), and the link to the theme of “Engage the world, Change the world” provides a common and urgent agenda (Fullan, Quinn, & McEachen, 2018; Quinn, McEachen, Fullan, Gardner and Drummy, 2020). The world is currently going down an extremely challenging path—one that calls for urgent, joint action that has leading in a culture of change as its common theme of salvation and flourishing.

As world problems continuously emerge and show up at our doorstep, and as we experience the virtues and uplifting impact of leaders who know how to lead and shape cultures of change we may, just may, see a rise in the quality of leadership, which at the current time is woefully weak.

David Sloan Wilson observed that “goodness can evolve, but only when special conditions are met.” One of these special conditions is the development of “leadership for and within cultures of change.” Ultimately, your leadership in a culture of change will be judged as effective or ineffective not just by who you are as a leader but by what leadership you produce in others. There is no time to waste.