Chapter Six

Coherence Making

CHANGE IS A LEADER'S FRIEND, BUT IT HAS A SPLIT personality: its nonlinear messiness gets us into trouble. But the experience of this messiness is necessary in order to discover the hidden benefits—creative ideas and novel solutions are often generated when the status quo is disrupted. If you are working on mastering the four leadership capacities we have already discussed—moral purpose, understanding change, developing team-based relationships, and building deep knowledge—you need to figure out how to integrate them. The mechanism for so doing is coherence making. This concept has become so important since I first wrote about it in 2001 that we have written a whole book on the topic (Fullan & Quinn, 2016). But first, let's set it up.

Striving for Complexity and Achieving Clutter

Humankind is capable of great rational thought, which turns out to be a liability. In the candy shop of change we want it all! Doug Reeves (2009) calls the problem initativitiis; many things ad hoc, one by one seemingly desirable. In education we have called these “Christmas tree” schools—so many superficial adornments.

Morieux and Tollman (2014) tell us that it is the same in business. The subtitle of their book is “how to manage complexity without getting complicated.” The authors were part of a group that created the “Complexity Index” by tracking the number of performance requirements at a representative sample of companies in the US and Europe from 1955 to 2010. The index shows that business complexity has multiplied sixfold over that period of 55 years. They state:

The real curse is not complexity so much as ‘complicatedness’ by which we mean the proliferation of cumbersome organizational mechanisms—structures, procedures, rules and roles—that companies put in place to deal with the mounting complexity of modern business. (p. 5)

Delving further into the number of procedures and rules, Morieux and Tollman calculated that a 6.7% increase annually in new procedures over the 55-year period resulted in a 35-fold increase. They reckon that managers in the top quartile spend 30–60% of their time coordinating meetings and writing reports—“work upon work” they call it. Touching base on one of our other indicators—engagement—Morieux and Tollman found that employees in organizations that scored high on the complexity index were three times more likely to be disengaged in their work. Further, the percentage of Americans who are satisfied with their work declined from 61% in 1987 to 47% in 2011.

Broadly speaking they argue that the solution is to develop cultures based on “autonomy and cooperation” (which the reader will notice is precisely what I concluded in Chapter 4 of this book). As they put it:

The simple rules do not aim at controlling employees by imposing formal guidelines and processes, rather, they create an environment in which employees work together to develop creative solutions to complex challenges. (p. 18)

All of this is compatible with what I have been saying throughout this book. In the book Coherence: The Right Drivers in Action for Schools, Districts, and Systems, Joanne Quinn and I addressed coherence more comprehensively in education (Fullan & Quinn, 2016).

Defining Coherence Making

Coherence is not alignment. The latter consists of the rational organization and explanation as to what the main pieces of the organization are and how they relate to each other: vision, goals, strategies, finances, accountability, training, and so on. If we addressed all of this rationally, it would bring us back to Morieux and Tollman's artificial complicatedness. Think of it this way:

- Alignment is rational.

- Coherence is emotional.

Rational explanations are less sticky—you have to memorize them. On the other hand, things you experience usually affect your emotions and stay with you. Thus, you must “experience” coherence. Our formal definition of coherence is:

The shared depth of understanding about the purpose and nature of the work. (Fullan & Quinn, 2016, p. 1)

I ask the reader to dwell on the definition. “Shared depth” is not something you can get from as document, a rousing speech, or even as good professional learning experience. I only know one way to develop “shared, collective understanding,” and that is through purposeful, day-to-day interaction. Coherence making is a cultural phenomenon. It is what you experience on a daily basis in the setting in which you work. If the collective culture is weak, there will be little retained learning. If it has the strength of collaborative professionalism, as we saw in Chapter 4, it has the ingredients for coherence making, as measured by the shared depth of understanding of the work and its outcomes. Learning in a culture of change includes learning deeply about the work as a group.

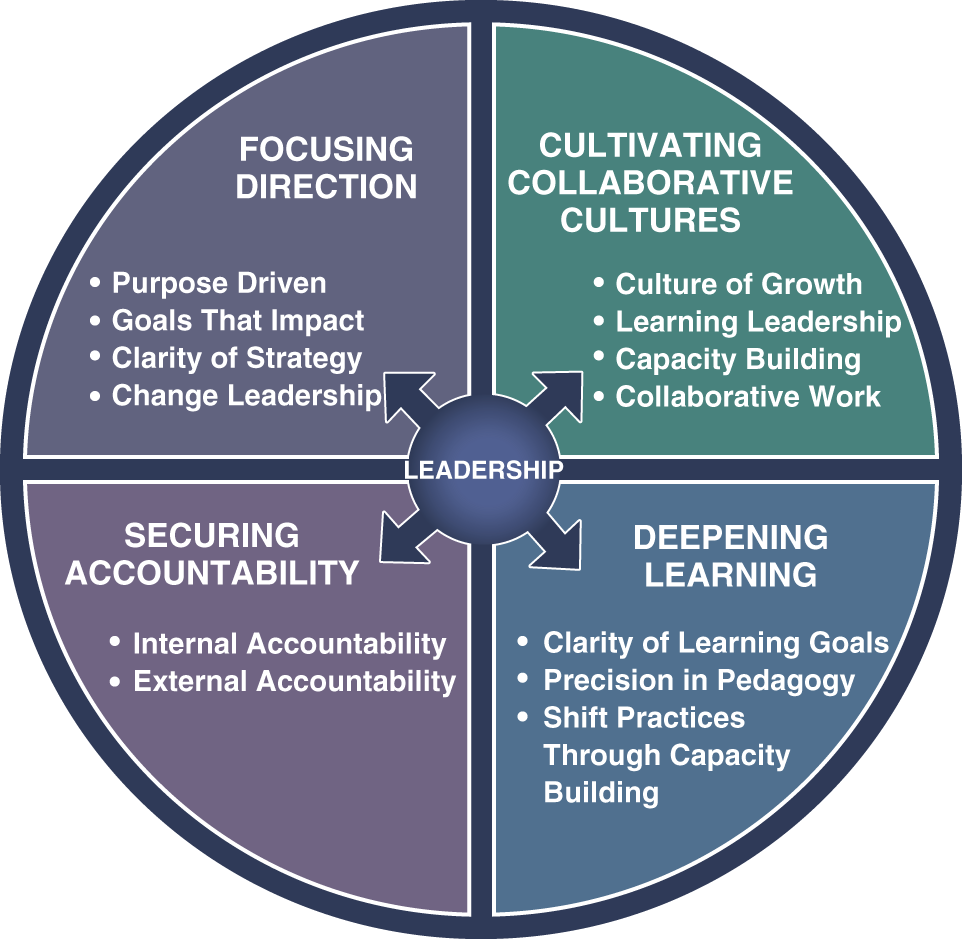

Our full Coherence Framework for Education is displayed in Figure 6.1, which is our attempt at avoiding clutter or making the complex too complicated. The framework has only four main components, yet it is comprehensive (i.e., covers the waterfront). It is also mutually exclusive (concepts don't overlap) and succinct (only four big pieces). We have discussed all of these elements across the chapters, so we can be brief here. Focusing direction is essentially about moral purpose, which is raising the bar and closing the gap for all students. We have added two critical elements to this definition. One is that we must consider clarity of strategy from the beginning of the process. Moral purpose does not go very far if it is not purposefully activated, as we discussed in Chapter 2. Second, as a result of our deep learning work we have widened the definition of moral purpose. At first it tended to be confined to literacy, numeracy, and high school graduation. After delving into Chapter 5, we see it as a matter of being “good at learning” and “good at life” (connectedness, and well-being)—see Quinn, McEachen, Fullan, Gardner, & Drummy (2020).

Figure 6.1. The Coherence Framework for Education.

Moral purpose is dynamically related to collaborative cultures. One could say that you cannot develop solid moral purpose in the absence of collaboration, which should be clear from our discussion of the nine insights into the change process (Chapter 3). In collaborative cultures, moral purpose is jointly determined by leaders and members through focused work.

Third, deep learning is essential for giving coherence substance. Content is crucial here. Finally, securing accountability is built into our model because it becomes part of the culture—literally a culture of accountability that is part and parcel of the work.

We also do not see the Coherence Framework as step by step. It is like a pulsating heart; when all four chambers are operating, the organization is healthy. In some ways, quadrants 1 and 2 can be thought of as going together. You can't really focus direction without interacting with others. Focusing direction means you should select a small number of ambitious goals (a maximum of three). Developing collaborative cultures is hard because in involves changing culture—the daily habits of people. In Chapter 4, we saw how specific and persistent the actions must be, and how peers must be part and parcel of changing culture. Deep learning (Chapter 5) represents another cultural change, literally changing the nature of schooling as we know it. Quadrant four requires integrating a new culture of accountability.

Coherence making is complex, but I hope the agenda is clear. Leadership is crucial, as we will take up in the next chapter. Basically, leaders need to be “coherence makers.” I can also note that coherence making is never completed. People come and go. Coherent systems have lower turnover of staff (because they are better places to work), but all organizations have turnover if you take any two or three years. Second, the environment changes—new policies and different political and demographic forces enter for better or worse. Third, hopefully you and your colleagues have new ideas along the way. All of these changes present additional coherence-making propositions. Coherent organizations have a more stable base, but they still must establish coherence making as an ongoing capacity.

Readers tell us that the Coherence Framework and its details are clear. We have 33 protocols aligned to support implementation (Fullan, Quinn, & Adam, 2016). People read the book, many times in study groups, and go away to implement the solution. Then they return and ask us, “How do you implement this stuff?” This involves another dimension of the change process: the nine change capacities in Chapter 2, for example. Change requires leadership that puts in the time to understand and work in each context, because each context in some respects is unique—a point we will return to in the next chapter.

In the meantime, if you appreciate that coherence is core, that you can only get it through thoughtful shared, purposeful interaction, and you must attend to it at all times—if you and your colleagues do all of these things daily, then you are in the game.

In effect, Chapter 4 on collaborative cultures addresses coherence in the individual organization. Recall Collins's flywheel effect when the interactive factors—such as passionate individuals, collaborative teams, good data, and so forth—generate ongoing focus.

Here I want to add to the challenge, “How do you achieve coherence when there are multiple subparts?” For example, the Toronto District School Board has 100 branch plants, or 583 schools. This takes us to our bigger “system coherence” framework that we call “leadership from the middle.”

Leadership from the Middle

When we shift our lens to the system level—multiple levels and units—the matter of coherence obviously becomes more difficult. In system change—let's say the whole organization assuming multiple units—there are at least three levels: top management, middle management, and individual local units. In education, for example, this includes, respectively, state level, districts, and local schools.

After years of attempts at whole system change, we know that top-down change doesn't work (too complex, too much turnover, people don't follow orders). We also know that bottom-up change is not the answer (too many ad hoc pieces and uneven development). New Zealand, for example, in 1989 established a radical new plan called “Tomorrow's Schools,” where each one of its 2,500 or so schools became autonomous with its own local board of governors. Over the ensuing decades, the gap between schools doing well or poor became significantly greater. In 2018, a new government established a new “Tomorrow's Schools Task Force” whose focus is how to coordinate schools to work together. It is still not determined what the solution will be, but hopefully ideas in leading in a culture of change will find a place.

If top-down doesn't work and bottom-up fails, where is the glue? We find it in the middle! Hargreaves and Shirley (2018) first surfaced this finding when they studied an initiative in Ontario, where the government funded a consortium of districts to implement a special education initiative. They found great cooperation across districts, innovations that had support, and results that the districts collectively had caused.

Our team has since developed “leadership from the middle” (LftM) as a major component of our system strategy. We are using LftM, for example, to guide and interpret the reforms in California. The government over the past six years has developed a radical new system transformation called the California Way (Fullan, Rincón-Gallardo, & Gallagher, 2019). Its goal is to achieve success for all students in the state in terms of measurable results in excellence and equity. There are 1,009 local districts and 58 counties, about 12,000 regular and charter schools, and more than 6 million students. Overseeing the system there is the governor, a state superintendent of public instruction (an elected position), the California Department of Education (CDE), and several other agencies.

When we introduced LftM into the California system, educators and others by and large loved it (not to say that implementation is smooth). The reason that LftM has appeal is that those in the middle find that they have a proactive role. My image of the traditional middle is that the top tells them what to do, while the bottom complains that they are doing it. In LftM, the middle becomes a system resource. In the case of California, the middle are districts and counties. The solution requires districts and counties to work more closely together locally (vertically so to speak), and laterally across districts and counties—and for all of these to work more closely with CDE and related agencies. After six years, progress is being made, with crucial next steps before them (see Fullan, Rincón-Gallardo & Gallagher, 2019).

Our formal definition of the middle is:

A strategy that increases the capacity of the middle as it becomes a better partner laterally, upward and downward.

Most groups instantly find LftM appealing. As I said, the vast middle immediately sees a potentially new positive role for them. We have encountered many people in higher education and in K–12 systems that start using LftM thinking right away. We are also using LftM with several systems around the world: California, Victoria, Australia, and in our Deep Learning initiatives such as in Uruguay (see Quinn et al., 2020).

These various applications have led to further development and thinking about system change. Figure 6.2 represents our latest thinking.

Apologies for the slick jargon, but the essence of Figure 6.2 is:

- The top shapes the direction, invests, interacts, monitors direction, and proactively liberates downward.

Figure 6.2. General principles.

- The middle increases its capacity, interacts laterally within the middle, exploits upward, proactively liberates downward, and demonstrates accountability.

- The bottom exploits upward, interacts laterally, and demonstrates accountability.

A few words require explanation. Although it is oddly put, exploit upwardly is the correct concept for system change. Levels below the top should not want to find themselves constantly on the receiving end of top-down polices. By exploit, I mean that the lower levels proactively take into account and act on government policies relative to local priorities. In a word, they exploit polices in relation to local priorities. Liberate those below you means that you want to free “groups” to act on policies with some degree of freedom. When individuals are free, they act randomly; when groups are free, there are checks and balances that combine autonomy and collaboration (see my discussion in Chapter 4).

If you ask, “Where is the glue (the accountability)?” the answer is that it is in the combination of the focuses and the purposeful interaction. Yes, continuous interaction vertically and horizontally about progress serves the accountability function better than traditional accountability. Transparent and focused interaction sorts out what is working and what is not. Note: There are still the measures of progress, but they operative in a more interactive, supportive climate.

Independent from us, Morieux and Tollman (2014)—the “manage complexity without getting too complicated” authors—arrived at the same conclusions. They call one of their recommendations “increase reciprocity” that includes the concept multiplexity (networks of interaction). Leading in a culture of change means increasing the capacity of individuals and groups to make better decisions and engage in corresponding actions. It is purposeful interaction on a daily basis that feeds such capacity. In effect, Morieux and Tollman argue that such interactions “create feedback loops that expose people, as directly as possible to the consequences of their actions” (p. 110).

Multiplexity, say the authors, consists of “creating networks of interaction.” Basically this takes us back to the collaborative cultures we discussed in Chapter 4. Teams doing the work get together regularly to review how things are going. Sometimes, this involves a given team examining its own work; other times teams compare notes, or engage in cross-visitations to learn from each other,

Morieux and Tollman conclude, as I do, that focused interaction—learning is the work—produces “greater accountability, less complicatedness” (p. 133). The objectives are ambitious combined with transparent actions and feedback that allow for corrective action:

These feedback loops allow for decentralized control, since it is based on the interaction among people, each one partly controlling the behavior of others. Control becomes distributed and flexible, as opposed to top down and rigid, which enables the organization to be more adaptive to changing conditions. (p. 134)

In pursuing leadership from the middle, we also acknowledge that many efforts at change are ad hoc and piecemeal in business and in education. I mentioned in Chapter 4 my work with Laura Schwalm, the former superintendent of Garden Grove Unified School District in Anaheim, California. As we do our current work in the state to increase the collective focus of districts improving learning for all students, we encounter the tendency to take on ad hoc initiatives that, by definition, undermine coherence. In the rush to solutions, people inevitably operate more superficially. To counter this problem, we compiled a simple guideline that we called “Getting Serious about Getting Serious” (Figure 6.3).

We see in Figure 6.3 that each of the 10 items are strong in their own right, and they operate as a cluster of mutually reinforcing factors that constitute a system that transforms the culture of learning. You will also see that our set of “getting serious” elements compares favorably with Susan Moore Johnson's (2019) account of schools “where teachers thrive” that I described in Chapter 4. The difference is one of scale. Most of the examples of success in Chapter 4 deal with individual schools, whereas my work with Schwalm is about entire school districts—system with 40 or more schools, for example.

In any case, leadership from the middle is a coherence maker for systems. Coherence making is an integral part of our model, as it serves to bring together moral purpose, new insights about the change process, and knowledge.

We have pursued system change more systematically in a new study where we examined the roles and relationships across three levels: local, middle and top in a book with the tantalizing title: The Devil is in the details: System solutions for equity, excellence and wellbeing (Fullan & Gallagher (2020).

| Getting Serious about Getting Serious Laura Schwalm and Michael Fullan January 2019 |

|

| For those who believe a school system cannot be better than its teachers and understand that if teachers are expected to thoughtfully build student capacity, the same thought must be given to teacher capacity building. We hope these scenarios will provoke your thinking. | |

| Scenario A: A system very serious about capacity building |

Scenario B: A system not serious about capacity building |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| While the scenarios above are designed to provoke thinking about how to build and sustain strong professional capacity building for teachers, training and coaching alone will not make a great teacher. The importance of hiring practices that yield teachers who have naturally high expectations for all students, combined with true caring for their achievement and well-being, is critical. Suffice it to say that if you expect your teachers to truly care about all of their students, your teachers must feel that you have the same care and concern for them. | |

Figure 6.3. Getting Serious about Getting Serious.

Conclusion

Remember from Figure 1.1 in Chapter 1 that the route to making more good things happen and preventing more bad things from occurring is a process that generates widespread internal commitment from members of the organization. When change occurs, there will be disturbances, and this means that there will be differences of opinion that must be reconciled. Effective leadership means guiding people through the differences and, indeed, making differences a source of new insights as they lead to more integrative and focused solutions. . . .

Working directly on coherence making is essential in a world that is loaded with uncertainty and confusion. But you do need to go about coherence making by honoring the change guidelines in previous chapters, which in effect require differences about the nature and direction of change to be identified and confronted. Rest assured, also, that the processes embedded in pursuing moral purpose, the change process, new relationships, and knowledge sharing do actually produce greater and deeper coherence as they unfold.

This is a time to emphasize that there is a great deal of coherence making in Figure 1.1 from start to finish. Moral purpose sets the context; it calls for people to aspire to greater accomplishments. The standards embedded in strong moral purpose in relation to outcomes can be very high indeed, as they are in the cases cited in this book.

This moral purpose–outcome combination won't work if we don't respect the messiness of the process required to identify best solutions and generate internal commitment from the majority of organization members. Within the apparent disorder of the process there are hidden coherence-making features. The first of these features is what can be called lateral accountability. In hierarchical systems, it is easy to get away with superficial compliance or even subtle sabotage. In the interactive system I have been describing, both good and bad work get noticed (or, more accurately, people recognize and sort out what is working). Over time, things that work get retained and what doesn't work gets discarded. This process is built into the culture of daily interaction.

We have come on a pretty complicated journey. I have said that leadership in a culture of change requires a new mind-set that serves as a guide to day-to-day organization development and performance. We obtained, I hope, a good sense of what the mind-set consists of and a good sense of how it plays itself out in actual cases from businesses and school systems.

Ideas about the new leadership required have been dispersed throughout the chapters. Also, the key leadership competencies have been implied rather than systematically considered. It is time to pull together more comprehensively what the new leadership looks like. Be prepared. It is different from what we might have assumed. It is, as you might have inferred, more dynamic, less linear, and, in a word, more nuanced.