Chapter Four

Relationships, Relationships, Relationships

IF MORAL PURPOSE IS JOB ONE, RELATIONSHIPS ARE job two, as you can't get anywhere without them. If you asked someone in a successful enterprise what caused the success, the answer almost always is, “It's the people.” But that's only partially true: It is actually the relationships that make the difference.

In pursuing the importance of relationships in this chapter, I will do something different. Let's talk about businesses as if they had souls and hearts, and about schools as if they had minds. We will see that moral purpose, relationships, and organizational success are closely interrelated. We will also find that businesses and schools have much in common. Businesses are well advised to boost their moral purpose—for their own good as well as for the good of society. Schools, particularly because we live in the knowledge society, need to strengthen their intellectual and social (group) quality as they deepen their moral purpose. We will conclude with what businesses and schools, in fact what all successful organizations, have in common, namely, “learning is the work” is their center of gravity.

Businesses as If They Had Souls

In “Relationships: The New Bottom Line in Business,” the first chapter of their book The Soul at Work, Lewin and Regine (2000) talk about complexity science:

This new science, we found in our work, leads to a new theory of business that places people and relationships—how people interact with each other, the kinds of relationships they form—into dramatic relief. In a linear world, things may exist independently of each other, and when they interact, they do so in simple, predictable ways. In a nonlinear, dynamic world, everything exists only in relationship to everything else, and the interactions among agents in the system lead to complex, unpredictable outcomes. In this world, interactions, or relationships, among its agents is the organizing principle. (pp. 18–19)

For Lewin and Regine, relationships are not just a product of networking but “genuine relationships based on authenticity and care.” The “soul at work” is both individual and collective:

Actually, most people want to be part of their organization; they want to know the organization's purpose; they want to make a difference. When the individual soul is connected to the organization, people become connected to something deeper—the desire to contribute to a larger purpose, to feel they are part of a greater whole, a web of connection. (p. 27)

It is time, say Lewin and Regine, to alter our perspective: “to pay as much attention to how we treat people—co-workers, subordinates, customers—as we now typically pay attention to structures, strategies, and statistics” (p. 27). Lewin and Regine make the case that there is a new style of leadership in successful companies—one that focuses on people and relationships as essential to getting sustained results.

It's a new style in that it says, place more emphasis than you have previously on the micro level of things in your company, because this is a creative conduit for influencing many aspects of the macro level concerns, such as strategy and the economic bottom line. It's a new style in that it encourages the emergence of a culture that is more open and caring. It's a new style in that it does not readily lend itself to being turned into “fix it” packages that are the stuff of much management consultancy, because it requires genuine connection with co-workers; you can't fake it and expect to get results. (p. 57)

Many other studies along the way have shown that companies that place high value on the quality of their employees end up doing best in the market. Recall that Sisodia, Wolfe, and Sheth (2007) identified firms of endearment, drawing their sample by developing a list of companies that met their “humanistic performance criterion,” that is, these companies paid equal attention to all five stakeholders (customers, employees, investors, partners, and society). Sisodia and his colleagues then examined the financial performance of these companies using the Standard and Poor's performance index over a 10-year period. They found that the firms of endearment outperformed the S&P index by 122% over that period. Several other studies have produced similar results.

These results do not just show that some companies produce better results because they are nice to employees. Most of all, they create and support the conditions for employees to be successful. As I said in The Six Secrets of Change, the best way for employers “to love their employees” is to create the conditions for their success. We have already seen in Chapter 1 that businesses have a very poor track in establishing the conditions for success. Chamorro-Premusic provides a nice twist on assessing leaders when he argues that “to judge leaders talent, we need to objectively consider their teams' performance” (p. 123). Put positively, he says, “The key goal of a leader should be to help the team outperform its rivals” (p. 122).

Other business authors echo the newly founded emphasis on relationships: Bishop (2000) argues that leadership in the twenty-first century must move from a product-first formula to a relationship-first formula; Goffee and Jones (2000) ask, “Why should anyone be led by you?” Their answer is that we should be led by those who inspire us by

- Selectively showing their weaknesses (revealing humanity and vulnerability);

- Relying on intuition (interpreting emergent data);

- Managing with tough empathy (caring intensely about employees and about the work they do); and

- Revealing their differences (showing what is unique about themselves).

This sets us up to consider schools. This question is more than a matter of “minds.” It also relates to the question of the quality of relationships in schools.

Schools as If They Had Minds

The key question is, do schools have collective minds? It turns out that this is a tricky question, and its answer seems encouraging, at least in the argument. The course of the argument goes in two parts: (i) a promising start; and (ii) autonomy, collaboration, and the promise of more.

A Promising Start: 1990s

Nothing presents a clearer example of school district reculturing than School District 2 in New York City. Elmore and Burney (1999, pp. 264–265) provide the context:

District 2 is one of thirty-two community school districts in New York City that have primary responsibility for elementary and middle schools. District 2 has twenty-four elementary schools, seven junior high or intermediate schools, and seventeen so-called Option Schools, which are alternative schools organized around themes with a variety of different grade configurations. District 2 has one of the most diverse student populations of any community district in the city. It includes some of the highest-priced residential and commercial real estate in the world, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and some of the most densely populated poorer communities in the city, in Chinatown in Lower Manhattan and in Hell's Kitchen on the West Side. The student population of the district is twenty-two thousand, of whom about 29 percent are white, 14 percent black, about 22 percent Hispanic, 34 percent Asian, and less than 1 percent Native American.

Anthony Alvarado became superintendent of District 2 in 1987. At that time, the district ranked tenth in reading and fourth in mathematics out of 32 subdistricts. Eight years later, by 1996, it ranked second in both reading and mathematics. Elmore and Burney describe Alvarado's approach:

Over the eight years of Alvarado's tenure in District 2, the district has evolved a strategy for the use of professional development to improve teaching and learning in schools. This strategy consists of a set of organizing principles about the process of systemic change and the role of professional development in that process, and a set of specific activities, or models of staff development, that focus on systemwide improvement of instruction (1999, p. 266).

The seven organizing principles of the reform strategy are as follows:

- It's about instruction and only instruction.

- Instructional improvement is a long, multistage process involving awareness, planning, implementation, and reflection.

- Shared expertise is the driver of instructional change.

- The focus is on systemwide improvement.

- Good ideas come from talented people working together.

- Set clear expectations, then decentralize.

- Collegiality, caring, and respect are paramount.

Elmore and Burney (1999, p. 272) explain:

In District 2, professional development is a management strategy rather than a specialized administrative function. Professional development is what administrative leaders do when they are doing their jobs, not a specialized function that some people in the organization do and others do not. Instructional improvement is the main purpose of district administration, and professional development is the chief means of achieving that purpose. Anyone with line administrative responsibility in the organization has responsibility for professional development as a central part of his or her job description. Anyone with staff responsibility has the responsibility to support those who are engaged in staff development. It is impossible to disentangle professional development from general management in District 2 because the two are synonymous for all practical purposes.

So, it looked like District 2 was an out-and-out success. And it was in its own right, but it did not last nor did the concepts travel well. Alvardo went on in 1998 to become Chancellor of Instruction (reporting to a Superintendent) at San Diego Unified School district and left in 2003 under a cloud of dissatisfaction and little success.

My point here is that this is part of a bigger story. We know that quality relationships and focused teamwork result in success. Schools are caring institutions that should have a leg up on this, but care by itself does not lead to increased performance. It has also been the case that studies of collaboration and “professional learning communities” as they are often called have been going on for four decades. So far they have proven little. I suspect the reason is that the quality of collaboration has been superficial and uneven.

Learning Is the Work

Let's shift focus and gears. What if we thought of the main function of organizations as “learning is the work”? When learning is confined to workshops, training, performance appraisals, and the like, we see the intended learning as one or more steps removed from actually doing the work.

Every important point in this book brings us back to culture. Culture is the way we do things around here. In successful organizations, the culture is based on daily learning built into daily interaction. Think of it this way: it is what happens in between meetings or workshops that counts.

Frederick Taylor is known as the father of scientific management. According to Taylor's studies in the steel industry, work tasks could be broken down, and workers could be taught to perform them with maximum efficiency and productivity. Taylor (2007) developed four principles of scientific management:

- Replace rule-of-thumb work methods with methods based on scientific study of tasks.

- Scientifically select, train, and develop each worker rather than passively leaving them to train themselves.

- Cooperate with workers to ensure that the scientific methods are followed.

- Divide work nearly equally between managers and workers so that the managers apply scientific management principles to planning the work and workers actually performing the tasks (p. 31).

Taylor was on the right track, but his approach was too literal and dehumanized to say the least. He was right about precision, but wrong about prescription. Taylor sought prescription; today, we want to figure out how to get consistent precision without imposing it. And we want it all—precision and innovation. Now that Tiger Woods is back in good graces, we can recall his Accenture ad: “Relentless consistency, 50%; willingness to change, 50%.”

The essence of learning is the work that concerns how organizations address their core goals and tasks with relentless consistency, while at the same time learning continuously how to get better and better at what they are doing through innovation and refinement.

Atul Gwande is a general surgeon at the Brigham and Women's Hospital in Boston. Let's start with a seemingly straightforward innovation: doctors and nurses regularly washing their hands. In his book Better, Gwande (2007) reports that every year, 2 million Americans acquire an infection while they are in a hospital, and 90,000 die from that infection. Yet one of the greatest difficulties that hospitals have “is getting clinicians like me to do the one thing that consistently halts the spread of infections: wash your hands” (p. 14). Hospital statistics show that “we doctors and nurses wash our hands one-third to one-half as often as we are supposed to” (p. 15).

As we will see with each of the examples in this chapter, successful workers mobilize themselves to be “all over the practices that are known to make a difference.” In Gwande's seemingly simple problem, it took consistent education, conveniences of hand-washing facilities, and frequent random spot checks to monitor and improve performance on something as simple as washing one's hands regularly.

We see time and again that new technology (in this case, hand-washing dispensers) is not sufficient to spur behavioral breakthroughs. Technology is at best an accelerator; culture is the driver.

Toyota has made a science of improving performance. The essence of Toyota's approach to improved performance in all areas of work consists of three components:

- Identify critical knowledge.

- Transfer knowledge using job instruction.

- Verify learning and success. (Liker & Meier, 2007)

This is not a “project, but rather a process that will require continued, sustained effort forever” (Liker & Meier, 2007, p. 82, italics in original). Welcome to “learning is the work”!

Liker and Meier make the critical point that going about identifying and standardizing critical knowledge is not just for technical tasks, such as those performed on assembly lines. To illustrate, they use three examples: manufacturing (bumper molder operator), a nurse in a busy hospital, and an entry-level design engineer. This universal applicability is a key message: consistency and innovation can and must go together, and you can achieve them though organized learning in context.

Liker and Meier estimate “that Toyota spends five times as much detailing work methods and developing talent in employees as any other as any other company we have seen” (p. 110). Then: “If we were to identify the single greatest difference between Toyota and other organizations (this includes service, healthcare and manufacturing organizations), it would be the depth of understanding among Toyota employees regarding their work” (p. 112, italics added).

On the question of whether focusing on the consistency of practice inhibits creativity, Liker and Meier reflect: Is Toyota producing “mindless conformity or intentional mindfulness?” Their response: Toyota places a very high value on “creativity, thinking ability and problem-solving” (p. 113). When the preoccupation is with the science of improving performance, you can be like Tiger Woods: nail down the common practices that work in relation to getting consistent results; at the same time, you are freeing up energy for working on innovative practices that get even greater results, including taking timeouts for major overhaul of what you are doing, as Tiger has done four times in his career.

The intent of standardized work is not to make all work highly repetitive, giving license to neo-Taylorites to robotize every tasks. Rather, the goal is to define the best methods for reducing “bad variation” (ineffective practice) in favor of practices that prove to be effective. We are not talking about 100% of the work. In most cases, write Liker and Meier, “the critical aspects of any work equal about 15–20% of the total work” (p. 143). The key is to identity those tasks and to take special care that everyone does those tasks well using the known best method of doing so. And “for these items there is no acceptable deviation from the defined method” (p. 144).

Liker and Meier (2007) then apply the approach to the tasks of a busy hospital nurse. After categorizing all aspects of the job into “core” and “ancillary” tasks, they break them down into routine and nonroutine elements. For example: starting an IV in a peripheral vein consists of six steps:

- Stabilize the vein.

- Place the tip of the needle against the skin.

- Depress the skin with the needle.

- Puncture skin with needle.

- Change needle angle.

- Advance the catheter.

For each of the six steps the authors identify “key points” with respect to safety, quality, technique, and cost.

No part of the work of consistent effective performance is static. In the midst of any action there is constant learning, whether it consists of detecting and correcting common errors or discovering new ways to improve. Let's make a return visit to education.

Education as a Slow Learner

I don't want to dis the work on collaboration between 1990 and the present—indeed, I have been part of much of it. Quite frankly, the yield from the work on collaboration in education has been limited. This is not to say that no good work has been done, only to indicate that on the ground it has not established the empirical case that effective collaboration is on the rise in school systems. My point in this section is twofold: There are both normative and practical obstacles to collaboration in schools; and recently there are signs as to what specific forms of collaboration are most likely to be effective.

All we have so far in education is that collaboration is probably a good thing. Actually, it isn't necessarily so. People can collaborate to do nothing or to do the wrong thing. The good news is that the research in the last three or four years has begun to pinpoint the ways in which collaboration can be effective. Not quite like Toyota, but with a good focus on precision. It starts with sorting out the relationship between autonomy and collaboration. Teachers have long argued for the importance of teacher autonomy. Others have called for more teamwork. It turns out to be a false dichotomy. Autonomy is not isolation. The latter is usually bad for you—whether at work or in life-long periods of isolation, resulting in decline. What if we thought of it differently? Today I am autonomous and have my ideas. Tomorrow I am with the group and contribute to it as well as learn from it, and so on. The idea is that you don't choose between autonomy and collaboration. You do both.

The most recent research—one could say research reported over the past three or four years—has given us much more specificity and clarity about the role of collaboration. I use five such studies here: the works of John Hattie and the related research of Jenni Donohoo and Steven Katz, Andy Hargreaves and colleagues, Amanda Datnow, Susan Moore Johnson (SMJ), and the Maori scholar from New Zealand, Russell Bishop.

John Hattie became famous 15 years ago in education by producing his meta-study analysis of “visible learning”—what teaching practices produced the best learning on the part of students. Feedback to students, teaching students to think about how they learn (meta-learning), and prior achievement were a few of the factors that had statistically significant effects (in the 0.4 to 0.5 effect size range). As Hattie pointed out, these effect sizes were modest but worth taking into account. A few of us pointed out that all the practices were “individualistic” endeavors. We asked, “What was the impact of collaborative activities?”

Hattie turned his attention to collective work and found indeed that it was much more powerful in its impact on student learning—a whopping 1.57 coefficient, much larger than he had ever found (Donohoo, Hattie, & Eells, 2018). The big question then became, “What is “collective efficacy?” Hattie and associated researchers found that it consisted of four factors: shared belief among teachers that they would produce results; primary reason was “evidence of impact”; a culture of collaboration to implement high-yield teaching strategies; and a leader who participates in frequent, specific collaboration. These four factors are consistent with our findings. Focus on powerful levers, enable all to engage, use peers to strengthen practice, and appoint leaders who participate in strengthening what works.

Donohoo & Katz (2020) proceeded to conduct a more thorough study of collective efficacy. The latter consists of the grounded belief that a group (of teachers for example) can make a difference in learning for all students—a belief that is based on cause and effect knowledge, goal-directed actions, and progressive inquiry (linking action, instructional improvement, and learning results). Increased collective efficacy as such is causally linked to measurable higher student achievement. Donohoo and Katz show what collective efficacy is, how it can be learned, and what impact it has on higher student achievement.

During this same period, Andy Hargreaves and his co-worker Michael O'Connor (2018) studied professional learning networks in seven countries. To start with, they said there is a big difference between “collaborative professionalism” and “professional collaboration.” The latter referred to professionals getting together (to do whatever); the former concerned collaboration that was based on “professionalism.” Specifically, they found that collaborative professionalism involved these issues:

- The joint work of teachers is embedded in the culture and life of the school.

- Educators care for each other as fellow professionals as they pursue their challenging work.

- They collaborate in ways that are responsive to and inclusive of the culture of their student, themselves, the community, and society (Chapter 9).

Similarly, Datnow and Park compared two high-poverty schools in California with two that were not successful. The difference, they said, was in the exact purpose and nature of collaboration. In the two successful schools there was specific “pedagogical” and “emotional” support. With respect to the former:

- Teachers didn't distinguish between formal and informal collaboration.

- There are candid, deliberative, supportive norms.

- They strive for continuous innovation and improvement.

- There is collective sense-making and integration of curriculum policy and existing practice (Chapter 3).

Datnow and Park (2019) also found a strong theme related to emotional support:

- Be buffered from external demands.

- Be a source for inspiration for improving practice.

- Lighten the burden around curriculum design and planning.

- Be a site for celebrating student learning (Chapter 6).

Another long-standing scholar of school cultures is Susan Moore Johnson (SMJ) from Harvard, who has also garnered new insights by going deeper into successful school cultures. One of the background studies that SMJ and her colleagues conducted was to trace 50 new teachers over a four-year period. They found that one-third had left teaching altogether and another third had changed schools. Teachers in low-income schools were less likely to benefit from mentoring and support than teachers from high-income schools, and thus less likely to continue as teachers.

As we will see later about hiring employees and appointing new leaders, most organizations pay scant careful attention to what they are doing and getting (see Cappelli: “Your approach to hiring is all wrong,” 2019). By contrast, in successful schools SMJ found major differences. These schools saw new hiring as a crucial part of the success of the schools. She lists the best practices in these schools (Johnson, 2019):

- Make fit a priority.

- Mission fit was essential.

- Endorsing the school's practices counted.

- Professional norms and practices matter.

- Expectations for ongoing development and collaboration were explicit.

- Invest in the recruitment and hiring process.

- Recruit a diverse pool of candidates from various sources.

- Screen candidates carefully.

- Organize school visits and interviews.

- Require a teaching demonstration and a debrief meeting (pp. 37–45).

As SMJ concludes: “This group of successful schools was remarkable in that each had developed a multi-step recruitment and hiring approach that engaged educators throughout the school in meeting and assessing candidates” (p. 46).

When it comes to collaboration, all schools studied by SMJ and her colleagues had teams of teachers working together, but there was a world of difference between the successful and nonsuccessful schools. In the latter schools, teachers “criticized their teams, saying that they didn't help them teach better, were misaligned with their school's larger purpose and programs, or focused excessively on improving test scores” (p. 86). Once again, collaboration per se is not the point.

By contrast, in the successful schools (note that all of the schools studied by SMJ were high-poverty, low-performing schools), principals and teacher teams worked together in setting aspirational purpose, promoting shared learning, not lockstep execution, and providing a psychologically safe environment for teams (pp. 89–90).

There is more: Teachers relied on their teams; cohort teams addressed students' needs, behavior, and organizational culture; aspirational purpose was well honed, sufficient predictable time was available to work together; ongoing, engaged support from administrators occurred; and there was ongoing facilitation by trained school leaders.

All of the schools in SMJ's study were located in the same state (Massachusetts). All three of the successful schools “improved rapidly” and “achieved the state's highest rating” (p. 97).

In sum, compared to earlier work (say, 2000–2015), the new collaborative work is built into the daily culture, is more specific, addresses both pedagogical and emotional support, and is linked directly to student learning. It is still limited in at least two ways: successful cases are very much in the minority, and we are just seeing “school change,” not change in districts or larger systems. Quality collaboration, in other words, is small scale and limited.

What we are witnessing in SMJs and other studies of effective collaboration are the exception and in an indirect way the failure of what I would call the narrow “human capital” strategy that I characterized as a “wrong driver” (Fullan, 2011). SMJ makes the same point in referring to the Rand evaluation of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation $575 million intervention in three large urban districts and four clusters of charter schools (Stecher et al., 2018). Despite the massive funds and ongoing evaluation and monitoring of the effort, “it failed to achieve its goals, having no appreciable benefits for students' achievement on standardized tests or their graduation rates” (Johnson, 2019, p. 234).

SMJ concludes:

Although it was ambitious, the strategy itself was too narrowly conceived, focusing on individual teachers while ignoring the schools in which they worked…This strategy does nothing to improve how those teachers do their work together in the context of the school—for example, ensuring that goals for student's learning are understood and shared by everyone, recognizing how their interactions with students both inside and outside class affect the school's culture, considering how well their curriculum and instruction align with what children experience within and between grades, establishing ways to track student progress through the school's program over time, and interacting with parents in ways that contribute to a better home–school relationship. (p. 234)

We see in the SMJ research that success requires a wholesale change in culture. Schools can mimic aspects of the required changes, as they engage in superficial collaboration that they inevitably find is not worth their time. I would estimate that fewer than 15% of schools and 10% of districts reflect the changes that SMJ is talking about. After 150 years of regular schooling, old cultures die hard!

One final reinforcer comes from Russell Bishop (2019), the Maori educator from New Zealand. He subtitles his book appropriately: “Relationship-Based Learning in Practice.” Bishop spent over 12 years working with 50 New Zealand secondary schools building cultures of “establishing extended-family like relationships [that] are fundamental to improving Indigenous Maori students' educational achievement” (p. xiv). Bishop shows clearly that “relationships are fundamental to learning,” especially for minority groups, and doubly especially for indigenous cultures that value personal relationships. But more than that, humans are hard-wired to learn through social connections. Bishop clearly shows that all students, and especially those least connected to regular schooling, require meaningful relationships in order to learn and develop.

Bishop (2019) found another aspect of traditional teaching culture that blocked change:

While many teachers took on board the need to develop positive extended family-like relationships in their classrooms, they did not follow it up be taking on board the need to change their teaching practices from traditional to dialogic and interactive. (pp. 29–30)

Bishop found that despite overall success in a publicly funded multiyear initiative he failed to garner continued funding. Bishop acknowledges that he did not pay sufficient attention to certain critical “sustainability factors,” including problems of developing sufficient and/or sustained capacity in teachers, problems with details of effective interactions, principal turnover, and the overall problem of lack of developing collective efficacy (pp. 37–47).

Bishop's overall model provides additional grist for the mill of deep and focused cultures of learning. He advocates three big action guidelines for leaders (Bishop 2019):

- Leaders create and extended family-like context for learning.

- Leaders interact within this context of learning.

- Leaders monitor the progress of learners' learning and the impact of the processes of learning (Chapter 8).

I have labeled this section as “education as a slow learner” in order to stress the point that we have known quite a lot about collaboration for some 50 years. Only lately—in the past five years or so—are we beginning to decipher the details and specificity with respect to the change in culture that will be required. This still represents to me an uphill battle, but at least we are in the game.

In the meantime, I would like to reinforce the critical point about “learning is the work” with another way of expressing it, namely, “learning in context.”

Learning in Context

To be blunt: learn in context or learn superficially. When it comes to context it seems that the focus on human capital—the quality of the individual—blinds us to the critical role of context. As Elmore (2000, pp. 2–5) notes:

Attempting to recruit and reward good people is helpful to organizational performance, but it is not the main point. Providing a good deal of training is useful, but that too is a limited strategy.

Elmore (2000) tells us why focusing only on talented individuals will not work:

What's missing in this view [focusing on talented individuals] is any recognition that improvement is more of a function of learning to do the right thing in the setting where you work than it is of what you know when you start to do the work. Improvement at scale is largely a property of organizations, not of the pre-existing traits of the individuals who work in them. Organizations that improve do so because they create and nurture agreement on what is worth achieving, and they set in motion the internal processes by which people progressively learn how to do what they need to do in order to achieve what is worthwhile. Importantly, such organizations select, reward and retain people based on their willingness to engage the purposes of the organization and to acquire the learning that is required to achieve those purposes. Improvement occurs through organized social learning… Experimentation and discovery can be harnessed to social learning by connecting people with new ideas to each other in an environment in which ideas are subject to scrutiny, measured against the collective purposes of the organization, and tested by the history of what has already been learned and is known. (p. 25; emphasis added)

This is a fantastic insight: learning in the setting where you work, or learning in context, is the learning with the greatest payoff because it is more specific (customized to the situation) and because it is social (involves the group). Learning in context is developing leadership and improving the organization as you go. Such learning changes the individual and the context simultaneously.

Human capital is ineffective unless it is coupled with its “more difficult to do” partner of changing the culture. Human capital at best is a short-term strategy. In education, to the extent that ongoing learning is addressed it is usually through professional development, workshops, and other external events. Sometimes learning is via PLCs (professional learning communities) or COLS (community of learners), which may appear to be part of context but are often episodic—a bit like saying, “I do something meaningful with my partner on Tuesdays.” Our Australian colleague Peter Cole (2004) ruefully calls professional development “a great way to avoid change” because it appears that learning is taking place, but little else happens in between workshops. Professional development programs or courses, even when they are good in themselves, are removed from the setting in which teachers work. At best, they represent a useful input, but only that. Once more, it is what happens day after day that counts—in the setting in which one works.

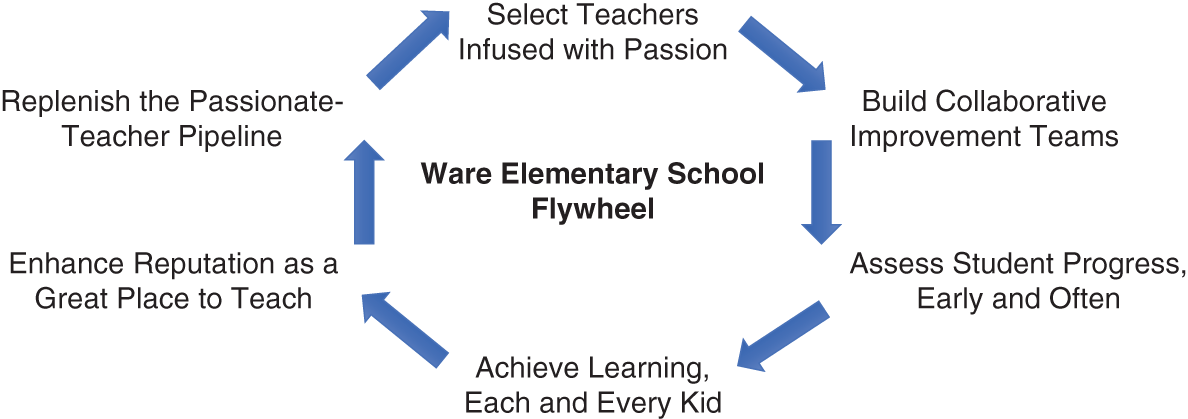

The remaining point to make is that the key factors identified in this chapter operate as a constellation of forces, (i.e., they feed on each other) as mutual strengths generate even more spinoffs because of the interaction effects. This is what Jim Collins was getting at in his identification of the “flywheel,” which he revisited in a recent brief monograph (Collins, 2019). The flywheel consists of a constellation of five or so key interrelated factors (e.g., hiring good people, having a focused collaborative culture, etc.). At the beginning, says Collins:

It feels like turning a giant, heavy flywheel. Pushing with great effort you get the flywheel to inch forward…You don't stop you keep pushing. The flywheel moves a bit faster…[it] builds momentum…then at some point—breakthrough! The flywheel flies forward with unstoppable momentum. (Collins, 2019, p. 1)

In other words, the heavy lifting of establishing a new focused collaborative culture is at the beginning—that critical first year. In year two, some momentum occurs, then in year three the payoff becomes evident and you get what Collins calls “the power of strategic compounding” (p. 1).

Collins stresses that it is not a list of static objectives, but rather, how one factor ignites another to accelerate momentum. Collins describes the case of Deb Gustafson, an elementary school principal in Kansas. Before examining the content of Gustafson's flywheel, Collins makes a key point that we will take up in Chapter 6 on “coherence”—something we call “leadership from the middle,” where the middle (schools, school districts, regional jurisdictions) does not wait for the top to initiate change: “Gustafson didn't wait for the district superintendent or the Kansas Commissioner of Education…to fix the entire system. She threw herself into creating a unit-level flywheel right there in her individual school” (p. 13). The particular flywheel Gustafson ended up with consisted of six factors (Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1. Ware elementary school flywheel.

At this point, Gustafson has 15 years under her belt. She stresses, “It's about culture, and the relationships and the collaboration with your teammates to improve and deliver for the kids—all that made us attractive to the right people” (p. 14).

In essence, the message of this chapter is that culture is core; that culture consists of a constellation of definable factors related to “learning is the work,” such as those on Figure 4.1. The work is hardest in the beginning, but propels forward faster by feeding the flywheel with inputs that have accelerating impact on what is already a powerful force.

One more example: Laura Schwalm was appointed superintendent of Garden Grove Unified School District (GGUSD) in Anaheim, California, in 1999. When she started, GGUSD was one of the lowest-performing districts in the state with a highly diverse and high-poverty student population of over 40,000 students. When Laura retired in 2013, GGUSD was one of the highest-performing districts in the state. How did she and her colleagues do it? In effect, Laura and her team built a better farm. One of her favorite sayings is, “Not only can you lead a horse to water, you can ‘salt the oats’ and they will drink.”

Laura and I now work together, and one of our current themes in relation school district improvement is, “What does getting serious about getting serious look like?” (compared to superficial reform). In Chapter 6 on coherence making, I will show you what we have so far. It's all about context.

Conclusion

With respect to leadership, there is still a strong case to be made for recruiting good individuals to the organization, and I will take up this matter in Chapter 7 when we examine the leadership continuum.

In the meantime, several key conclusions are warranted. There is more to relationships than relationships. Effective relationships have a certain quality. They have a strong emotional component (supporting each other when times are tough or individuals are down). And they have a getting better at the daily work dimension (striving for good consistency about what works and seeking innovations that make performance all the more effective). There is a constellation of a small number of factors related to changing culture that can serve as a flywheel in Collin's sense, thereby accelerating quality change once these factors are established.

I mentioned above—building better farms. There is an old song from World War I with the lyrics “How ya going to keep them down on the farm once they've seen Paree?” Learning in context raises the alternative, “How ya going to keep them down on the farm once they've seen the farm?” If the farm is no good, they are not going to stay long (read teacher turnover). Good farms provide good contexts for learning. People want to stay in contexts of learning—because they grow, because they get more done, because they are emotionally committed to others and to the mission of the place. Get this right and you have won more than half the battle.

Relationships are central to success but must develop toward greater mutual commitment and specificity related to the purpose of the work. From a change perspective, there is an interesting side benefit. In good collaborative work, you don't have to impose ideas because they are built into the culture. Quality collaborative cultures produce precision of practice without having to resort to prescription. Only changes in daily culture are strong enough to alter behavior and beliefs.

When cultures fundamentally improve in the way I have been describing in this chapter, the added bonus is that organizational accountability becomes established. I have called traditional approaches to accountability (tests linked to rewards and punishment) a “wrong” policy driver (because it backfires). Our focus on transparent and specific use of performance data turns accountability on its head as use of evidence becomes part of everyday work. Elmore (2004) put it this way:

Investments in internal accountability must logically precede any expectation that schools will respond productively to external pressure for performance. (p. 15)

In our “leading in a culture of change” we have built in accountability within the day-to-day interactions. In Nuance I called this a “culture-based accountability.” It includes the use of external data, and when required, external intervention—the latter is used selectively (i.e., when persistent failure occurs or in cases of fiscal and other malfeasance). Internal accountability works because it is transparent, specific, nonjudgmental, and above all, because people can see what is going on as they build mutual commitment to getting results. The latter—making progress—propels them to do even more.

Where the world is heading (where it needs to head) makes businesses and schools less different than they have been in the past. These days both businesses and schools need to be concerned with moral purpose and good ideas if they are to be successful and sustainable organizations. The laws of nature and the new laws of sustainable human organizations (corporations and public schools alike) are on the same evolutionary path. To be successful beyond the very short run, all organizations must incorporate moral purpose; respect, build, and draw on human relationships; and foster purposeful collaboration inside and outside the organization. Doing these things is for the good of the organization, and for the good of us all. Getting collaboration right is central to cultures of change.