Chapter Three

Nuance: Understanding Change

UNDERSTANDING THE CHANGE PROCESS IS LESS about innovation and more about innovativeness. It is less about strategy and more about strategizing. And it is rocket science, not least because we are inundated with complex, unclear, and often contradictory advice. Micklethwait and Wooldridge (1996) refer to management gurus as “witch doctors” (although they also acknowledge their value). Argyris (2000) talks about flawed advice. Mintzberg, Ahlstrand, and Lampel (1998) take us on a Strategy Safari. Drucker is reported to have said that people refer to gurus because they don't know how to spell charlatan!

Frame the Work as a Learning Problem, Not an Execution Problem

Effective change is a learning proposition (Google, 2019). This chapter is about insights into the nature of change. Across the chapters and in the final chapter I will have more to say about leadership for change. For now I want to convey the mysteries and magic of change itself—ideas that we and others have learned over the years including more recently identifying change's nuances (Fullan, 2019).

Would you know what to do if you read Kotter's Leading Change, in which he proposes an eight-step process for initiating top-down transformation (1996, p. 21)?

- Establish a sense of urgency.

- Create a guiding coalition.

- Develop a vision and strategy.

- Communicate the change vision.

- Empower broad-based action.

- Generate short-term wins.

- Consolidate gains and producing more change.

- Anchor new approaches in the culture.

Would you still know what to do if you then turned to Beer, Eisenstat, and Spector's observations (1990) about drawing out bottom-up ideas and energies?

- Mobilize commitment to change through joint diagnosis [with people in the organization] of business problems.

- Develop a shared vision of how to organize and manage for competitiveness.

- Foster concerns for the new vision, competence to enact it, and cohesion to move it along.

- Spread revitalization to all departments without pushing it from the top.

- Institutionalize revitalization through formal policies, systems, and structure.

- Monitor and adjust strategies in response to problems in the revitalization process [cited in Mintzberg et al., 1998, p. 338].

What do you think of Hamel's advice (2000) to “lead the revolution” by being your own seer?

- Step 1: Build a point of view.

- Step 2: Write a manifesto.

- Step 3: Create a coalition.

- Step 4: Pick your targets and pick your moments.

- Step 5: Co-opt and neutralize.

- Step 6: Find a translator.

- Step 7: Win small, win early, win often.

- Step 8: Isolate, infiltrate, integrate.

And, after all this advice, if you did know what to do, would you be right? Probably not. The biggest problem is that there are no hints about the process of change that would accomplish the recommended goals. There is no notion of partnership (other than you should have some), or even taking into account the people who have to lead change on the ground. Some of the advice seems contradictory. (Should we emphasize top-down or bottom-up strategies?) Much of it is general and unclear about what to do—what Argyris (2000) calls “nonactionable advice.” This is why many of us have concluded that change cannot be managed in a literal sense. It can be understood and perhaps led, but it cannot be controlled.

After taking us through a safari of 10 management schools of thought, Mintzberg et al. (1998) drew the same conclusion when they reflected that “the best way to ‘manage’ change is to allow for it to happen” (p. 324), “to be pulled by the concerns out there rather than being pushed by the concepts in here” (p. 373). It is not that management and leadership books don't contain valuable ideas—they do—but rather, that there is no “answer” to be found in them. Nevertheless, change can be led, and leadership does make a difference.

Becoming change savvy gets us into the socio-psychology of change, essentially forming your actions based on what you know or can come to know about the people that are part of the change process in which you are engaged. Recall that I have concluded that 80% of our best ideas come from leading practitioners. Mintzberg (2004) gets at this same point when it says that managing change “is as much about doing in order to think as thinking in order to do” (p. 10). In Mintzberg's terms effective leaders (managers he calls them) have to know that:

through complex phenomena, they have to dig out information, they have to probe deeply in the ground, not from the top; (p. 52)

Strategy is an interactive process, not a two-step sequence; it requires continual feedback between thought and action. Put differently, successful strategies are not immaculately conceived, they evolve from experience…Strategists have to be in touch; they have to know what they are strategizing about; they have to respond and react and adjust, often allowing strategies to emerge, step by step. In a word, they have to learn. (Mintzberg, 2004, italics in original)

Understanding change means understanding people—not people in general but people in specific (i.e., the ones you are leading right now). More Mintzberg:

Leadership is about energizing other people to make good decisions and do better things. In other words, it is about helping to release the positive energy that exists naturally within people. Effective leadership inspires more that empowers; it connects more than it controls; it demonstrates more than it decides. It does all of this by engaging—itself above all, and consequently others. (p. 143)

It seems elementary to say that change is about interaction with people, but that is exactly the essence of the matter. Have good ideas but process them, and get other ideas from those you work with, including—no, especially—those you want to change. We now know that the more complex the change, the more that people with the problem must be part of the solution.

Based on the past 40 years of studying and doing change my team and I have developed certain insights about the process of change. We have tested them against the research literature, and with others working closely in hundreds of change situations. I call the set of insights “the skinny on becoming change savvy” (Fullan, 2010; see Figure 3.1). Consider this list the wisdom of the crowd. Think of the nine strategies in concert, not as standalone.

Figure 3.1. Becoming change savvy.

1. Be Right at the End of the Meeting

As David Cote retired at the end of a long-distinguished career as CEO of Honeywell, he was asked, “What is the most important lesson you have learned about leadership?” This is what he said:

Your job as a leader is to be right at the end of the meeting, not at the beginning of the meeting. It's your job to flush out all the facts, all the opinions…because you'll get measured on whether you made a good decision, not whether it was your idea in the beginning.

I have a reputation of being decisive. Most people would say that being decisive is what you want in a business leader, but it is possible for decisiveness to be a bad thing. With bigger decisions you make bigger mistakes. (Quoted in Bryant, 2013)

In a later publication I elevated this insight into the first principle of nuance (Fullan, 2019). Complex change must be approached as a matter of joint determination. The more complex the problem, the more that people with the problem must be part of solving the problem. This is not just a matter of commitment. It is that people with the problem will have some of the best insights—insights that can only be accessed through interaction between and among leaders and others in the situation.

2. Relationships First (Too Fast/Too Slow)

Think about the last time you were appointed to a new leadership position and you were heading for your first day on the job. These days, all newly appointed leaders, by definition, have a mandate to bring about change. The first problem the newcomer faces is the too-fast-too-slow dilemma. If the leader comes on too strong, the culture will rebel (and guess who is leaving town—cultures don't leave town). If the leader is overly respectful of the existing culture, he or she will become absorbed into the status quo. What to do? Take in the following good advice from Herold and Fedor (2008). Change-savvy leadership, they say, involves:

- Careful entry into the new setting;

- Listening to and learning from those who have been there longer;

- Engaging in fact-finding and joint problem solving;

- Carefully (rather than rashly) diagnosing the situation;

- Forthrightly addressing people's concerns;

- Being enthusiastic, genuine, and sincere about the change circumstances;

- Obtaining buy-in for what needs fixing; and

- Developing a credible plan for making that fix.

What should strike you is not the charismatic brilliance of the new leaders but their “careful entry,” “listening,” and “engaging in fact-finding and joint problem solving.” In other words, attend to the new relationships that have to be developed. There are situations, of course, where the culture is so toxic that the leader may need to clean house. Or there might be one “derailer” that stands out, whom few like, and who requires immediate action (get the wrong people off the bus), but by and large, leaders must develop relationships first to a degree with the people in the situation before they can push challenges. You get only one chance to make a first impression, and it had better be a good one—not too fast, nor too slow.

Steve Munby, when he was appointed the CEO of the National College of School Leaders in England in 2001, knew about the too-fast-too-slow skinny. The National College had lost its focus under the previous CEO, trying to be all things to all people. Steve knew that refocusing was essential. He had some ideas, but the first thing he did was make 500 phone calls to school heads across the country asking them what the college meant to them, what it could do to serve them better, and so on. One month later (it takes a while to phone 500 people and make a personal connection), he had conveyed to the college that change was coming and that he was going to listen and act. The college went on to reestablish a strong presence in the field, helping to develop school leaders across the country and to prepare and support the next generation of school heads. He moved fast, but not too fast, and he was careful to build relationships as he went (Fullan, 2010, pp. 18–19).

Munby (2019) went on to write his professional autobiography that shows how he blended relationship building and organization development in three very different settings. Munby also shows that each new situation represents having to learn new things. His whole career, and it has been impressive, is captured in the title of his book, Imperfect Leadership. Each new context requires new learning. Humility and confidence seem to go hand in hand.

In my book Nuance, the finding is that effective leaders must become deeply “contextually literate”—they must understand with some depth the cultures in which they work. Now think of moving to a new position. My colleague Brendan Spillane from Western Australia provided this additional insight as we talked through nuance. He offered that every time a leader moves to a new organization or department, he or she becomes “automatically de-skilled,” i.e., does not understand the new culture. Reconciling too fast/too slow is to understand the context as it is and as it could be. Not to be too literal, but we have found that it takes six months or so of immersion to gain some understanding of the context as you consider with others the nature of the change direction.

3. Acknowledge the Implementation Dip

At first, this seems obvious; then we can get more complicated. Herold and Fedor again have the insight, finding in business what we have found in education.

When you introduce something new, even if there is some preimplementation preparation, the first few months are bumpy. How could it be otherwise? New skills and understanding require a learning curve.

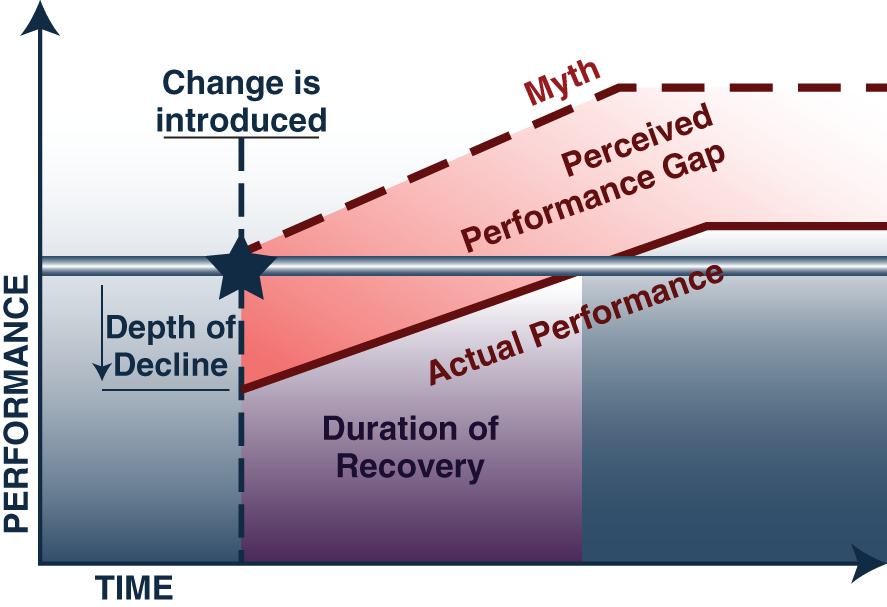

Figure 3.2 furnishes additional insights. First is the myth of change: that there will be some immediate gains. It can't be thus, by definition. Second, look inside the “depth of decline” triangle. If you are an implementer, the costs to you are immediate and concrete, while the benefits are distant and theoretical. In other words, the costs–benefits ratio is out of whack in favor of the negative. Third, if you are a leader, don't expect many compliments. People are not having a good time. Thus, leaders should be aware that their job is to help the organization get through the process to the point where benefits start to accrue. One way of thinking of change leadership is that the goal is to shorten the duration of the implementation dip to the point where benefits outweigh costs.

Figure 3.2. The myth and reality of change (Herold & Fedor, 2008).

Let's return more pointedly to the human element. People are not widgets, even though many a leader wishes they were. Change stands or falls initially not on the cognitive rationale and understanding of the change but more on the emotional connection to the change. Change is “sticky” when it connects to people's emotions not their rational minds. The old adage that captures this is, “People may not remember what you said, but they will remember how you made them feel.” To make matters more complicated, it is not that the “rational proposers” are correct and the “emotional” responders are wrong. We know that the former can be dead wrong and the latter alive right. The dynamics of ideas and emotions via the relationships of leaders and implementers contain the answer to effective change.

In our work over the past two decades we have found that the initial stages of change—say, those first few years—are more complicated than we first had realized. Even if the change is definable, the development of individual and collective capacity takes longer and requires greater effort than we thought. For example, consider our work in California with leaders across all levels. The state, the counties (N = 58), and the districts (N = 1009) have broadly endorsed the new direction since 2013. We are finding that “capacity to implement” is still the major stumbling block—even though the majority of implementers endorse the change (Fullan, Rincón-Gallardo, & Gallagher, 2019).

Most often in these cases, there is agreement about the change itself, followed by superficial implementation—and in some cases, they are unaware that what they are doing is superficial, believing that they are following the precepts of the innovation. And, in turn, they may mistakenly reject the innovation (we tried that…).

Another aspect of the dip is that many of the innovations being pursued—say, those of deep learning (see Chapter 4)—are indeed innovations where the initial phases entail working out the nature of the change itself. It is more development than dip.

4. Accelerate as You Go

Does the dip slow you down? If you ignore the dip and plow ahead, you have the illusion of change. On the other hand, if you dwell on the possibility of the dip, you may get nowhere. Sooner than later, the best way of building momentum is through purposeful action. Later in the chapter we will meet Wendy Thompson, who spent a whole year having local meetings with constituents, literally night after night getting ideas for a vision and strategic plan, and testing possibilities, only to find at the end of the year that only 20% of the people had heard there was a vision-building exercise, and most of them were against it.

Wendy Thompson had spent her time talking about hypothetical matters that had no meaning to the people in the constituency. It was all talk, without any action-based learning.

So getting to action sooner rather than later is key; it's not like you start things and wait for the implementation dip to play itself out. There is a great deal of activity that involves the leader. I used the label “go slow to go fast” to capture what needs to happen. Here is one of many examples we could use.

Michelle Pinchot, a principal in Garden Grove Unified School District, California led a successful turnaround effort in a school called K3 Peters, which had 600 children ages 5 to 9. When she arrived in 2011, school performance in literacy, for example, was stagnant. At the same time, the staff was congenial as a group but there was little in-depth focus. The school became successful within four years, reaching double-digit gains (11%) in a single year. We filmed the school as an example of success (see video, K3 Peters, www.michaelfullan.ca). But this is not my main point.

In the summer of 2016, Michelle was transferred to another large elementary school in Garden Grove called Heritage that was low performing. We decided to conduct an experiment. I said to Michelle, “You know a lot about getting success; let's see how quickly that you and the staff can improve Heritage” (see also Fullan & Pinchot, 2018). I said that all I would do would be to ask her by email every six months for two years questions like: What was the lay of the land when you arrived in the summer of 2016? What did you decide to do for the first six months? Six months later, I send a similar note, and six months later asked, “How is it going? What's next?” And so on.

By the second year, the school increased literacy and math scores, as measured by the new state test. The district conducts an annual climate survey that is based on criteria of an effective learning environment. Table 3.1 displays the results.

Table 3.1. Heritage Staff Responses, 2016−2018

| 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | |

| Students feel safe at school. | 71% | 94% | 94% |

| Site leadership fosters professional growth and feedback. | 30% | 86% | 100% |

| This school promotes trust and collegiality among staff. | 68% | 88% | 100% |

| This school has a safe environment for giving peer-to-peer feedback. | 44% | 93% | 100% |

| Students ask questions when they don't understand. | 33% | 71% | 86% |

The changes in culture are stunning given that they occurred within two years. How did Pinchot and her staff do it? At a general level, they focused on many of the specific strategies of focused collaboration that we examine in the next chapter.

Michelle exemplified many of the attributes that we see in lead learners. She spent the first several months setting the stage (we need to do something about literacy, and we will do it together); she established permanent teams led by teachers (in which she participated); she enabled collaborative teams to observe, collect information, and help solve problems.

Michelle Pinchot embodies several of what we have come to call our “sticky phrases” about change (insights that are powerful and stick with you). Here are three:

- “Go slow to go fast” (what seemed slow in the first six months was tantamount to “start your engines”).

- “Use the group to change the group” (multiple groups were focused; Michelle was present and enabling; new teachers leadership in particular groups flourished).

- “Talk the walk” (more and more teachers (and students) learn to explain what they are doing and why). If people talk the walk every day to each other, it is a sign that both specific things are happening and that people are learning every day (our change in culture; interaction and talk the walk is daily, not just episodic).

In short, leading in a culture of change leaders don't think of the implementation dip per se. They believe that they are in the early stages of a rapidly improving enterprise that is highly challenging but exciting because it is working with others to do something that is crucial, and that brings people to new heights of accomplishment and pride. When it works, leaders are just as happy for the adults as they are for the students and their families.

5. Beware of Fat Plans

We have found that there is a tendency for leaders to over plan on paper. Our colleague Doug Reeves (2009, p. 81) captures this phenomenon wonderfully: “The size and prettiness of the plan is inversely related to the quality of action and the impact on student learning.” Later Reeves (2019) wrote a book on “finding your leadership focus,” where he showed that too many ideas lead to the “law of initiative fatigue.” “Too fat or too many” ideas at the front end overloads the change process.

From 2000 to 2009, we worked with York Region (a very large multicultural district just north of Toronto). The district started with a 45-page implementation plan in 2007, then a 22-page plan in 2008, and an 8-page plan in 2009. In the course of this decade, York Region became one of the top-five performing school districts in the province of Ontario. It seems that the more you know, the briefer you get when it comes to plans. The emphasis shifts to action early and throughout the process. As we will see in Chapter 6, shared coherence is what matters, and you get this from specific action guided by brief focused documents, not from large documents.

Why are planning and plans so seductive? There are no people on the pages! PowerPoint slides don't talk back. We meet John Malloy a few times in this book; he is the director (superintendent) of the mammoth Toronto District School Board (TDSB) with its 583 schools. When he first arrived he observed, “I inherited a culture that expected templates, recipes, and road maps.” TDSB had the greatest documents and planning guides in the world of education; but they came and went. Malloy replaced the system of elaborate written plans with a system of interaction build around focused goals and briefer documents. You can test the efficacy of your written plans by asking implementers to “talk the walk” with each other with the goal of making the plans “living documents” (see the Malloy case study in Fullan, 2019, pp. 51–61).

6. Behavior before Beliefs

Don't be too literal. Of course, beliefs matter and leaders should work on them from day one. But if the issue is changing beliefs, you want to use the stimulant of new behavior early in the process. This phenomenon goes back at least to Leonardo da Vinci, whom I have called “the patron saint of nuance” (Fullan, 2019). Leonardo referred to himself as a discepolo della sperientia or a disciple of experience and experiment. “My intention is to consult experience first,” he wrote in his notes (Isaacson, 2017). Da Vinci wanted detail so that his ideas could expand from that basis.

Recall earlier when I discussed how one might change a teacher's beliefs about whether all children (his or her students, for example) could learn. I showed that such beliefs would not be shaken by research evidence, or moral exhortation, but rather, through having new experiences in relatively nonthreatening circumstances with help from a leader or peer whereby his or her students responded differently (i.e., they started learning).

It's a far cry from da Vinci to Jamie Oliver, but the comparison fits. Jamie was stymied with the problem of changing eating habits of secondary school students from obviously unhealthy choices (as in, you get sick or reduce your life span). His first challenge was Nora, the head dinner lady, who would have no part of his fancy ways. She has over 1,000 mouths to feed, on time, and at 37 pence a stomach. He tried to work alongside Nora but couldn't do anything right according to her. Partly for his own sanity (“I have to get out of her kitchen”), and partly to have her experience what it was like to cook properly, he arranged her to spend a week working with his chefs at his famous London restaurant called Fifteen. The chief chef, Arthur Potts, began to teach Nora basic knife skills in cutting vegetables; then he moved on to not overcooking, and then to a rule she had never heard of: never send a dish out that you have not tasted. She did taste one of Arthur's dishes, but it was so delicious that she sat down and ate the whole bowl. Gradually, these new behaviors began to make sense to Nora. She altered her beliefs, and working with Jamie altered the eating habits of an entire secondary school.

We see another of our sticky phrases in action here: “Go outside to get better inside.” Many people have not had experience outside of their own setting. The culture they are in reinforces their blinkered vision. Give people new experience in relatively nonthreatening circumstances and give them an opportunity to talk about it with others and peers.

Change is strange sometimes because it is not always logical. How many times have you heard the litany of reactions to an obviously promising idea: It won't work here; we tried that; we don't have time; and so on. I slightly (but only slightly) exaggerate in saying: If you want to kill a good idea, mandate it! You are far better off to expose people to good ideas, use the group to change the group, and participate as a learner. The change moral is, “Give people experience in the new way,” as a starting point for considering particular changes.

7. Communication During Implementation Is Paramount

Another way of thinking about guidelines 1–6 is to worry early about what might happen during implementation, don't talk about change too long before moving ahead, and once you do, start a change increase communication from day one.

Consider Wendy Thompson, whom I referred to above. Several years ago, Thompson was appointed the chief executive of Newham Council, a very large municipality in England. She spent a whole year conducting forums of discussion about a new vision, talking to thousands of people, only to find from a survey after 12 months that 80% of the people had never heard of the vision, and of the remaining 20%, 80% of them were against the vision. A year's hard work produces 4% in favor!

Our newest finding about leadership corroborates this lesson (communication during implementation is paramount). Leaders who “participate as learners” with staff in moving the organization forward have the most impact (Fullan, 2014, 2017). Once change starts in practice, the leader better be there!

Communication during implementation serves a double function. On the one hand, it gives the leader an opportunity to learn how implementation is going. As the leader gets specific insights about what is working, he or she can feed that back in both small and large forums. On the other hand, problems get identified more readily and can be addressed.

When you come to think about it, almost everything I say in Motion Leadership is about “leading in a culture of change.” It is about ongoing daily, focused, inside-and-out communication while doing the work.

8. Excitement Prior to Implementation Is Fragile

Maybe this is what is meant by the phrase “anticipation is greater than fulfillment.” How often have you witnessed or been part of a group where members declare: “I'm in! Let's do it,” and variations on the theme. The point is not to dampen initial enthusiasm, but rather to realize that genuine excitement comes from accomplishing something, not imagining it. Thus, knowledgeable leaders strive for small early successes, acknowledge real problems, admit mistakes, protect their people, and celebrate success along the way. The other eight insights in this chapter all channel change into accomplishments worth celebrating. Even setbacks are seen as problems to be solved, resulting in an even greater sense of fulfillment once they are addressed. Guideline 8 is a reality check, so that quality implementation is treated as problematic.

Successful change is a crescendo, not a rally. In successful cases, people work gradually at first, and then with greater intensity as they reach a culminating point of success where it is obvious, for example, that students are learning and producing at levels never before achieved. Organizations work toward and celebrate their periodic crescendos, and avoid faking them through empty celebrations.

9. Become a Lead Learner

Lead learner is the theme across the chapters of this book, so I need only identify the parameters here. It consists of six overlapping aspects:

- Participating as a learner.

- Listen, learn, and lead, in that order.

- Be an expert and an apprentice.

- Develop others to the point that you become dispensable.

- Be relentlessly persistent and courageous about impact.

- Focus on the “how” as well as the “what” of change.

Leading change is about helping others focus and learn. As we move into an era where more innovation is required, not the least because existing institutions are failing, we need leaders who will help the group achieve new, more effective steady states with the parallel capacity of adjusting to and taking advantage of new opportunities. Recall Schein's definition of culture: “constantly processing with the group external factors and internal integration” in relation to core goals (moral purpose).

Once you have your house in dynamic order, it is easier to maintain the stance toward continuous improvement and innovation. The important point is to be in charge of your own development, and in many ways to please external constituents simultaneously. There is an increasing number of challenges in the environment, but there are also more opportunities. Leading in a culture of change represents new external and internal dynamics.

Our own “deep learning” is a case in point (Fullan, Quinn, & McEachen, 2018). We start with the finding that the status quo—the way schools are—is no longer fit for purpose. Almost four out of five students are disengaged from school learning, inequity is rapidly on the rise, anxiety and stress among the young of all socioeconomic groups is steadily increasing. All signs point to change. But what change? We have worked with some schools around the world to develop a model of change that consists of six global competencies (character, citizenship, collaboration, communication, creativity, and critical thinking) and four aspects of the learning environment.

While many school leaders have joined us, it is clear that it takes a certain amount of risk taking (getting out of one's comfort zone) to develop the new ideas under conditions of uncertainty and doubt on the part of others. More and more, we can predict that leaders will have to operate under conditions of growing problems on the one hand and uncertain solutions on the other. Leaders will need all five leadership stances as they proceed through the next decade and more.

Conclusion

As leaders contemplate alternatives, it is probably good for them to rethink resistance. We are more likely to learn something from people who disagree with us than we are from people who agree. But we tend to hang around with and over-listen to people who agree with us, and we prefer to avoid and under-listen to those who don't. Not a bad strategy for getting through the day, but a lousy one for getting through the implementation dynamics.

Resisters are crucial when it comes to the politics of implementation. In democratic organizations, such as universities, being alert to differences of opinion is absolutely vital. Many a strong dean who otherwise did not respect resistance has been unceremoniously run out of town. In all organizations, respecting resistance is essential, because if you ignore it, it is only a matter of time before it takes its toll, perhaps during implementation, if not earlier.

For all these reasons, successful organizations don't go with only like-minded innovators; they deliberately build in differences. They don't mind so much when others—not just themselves—disturb the equilibrium. They also trust the learning process they set up—the focus on moral purpose, the attention to the change process, the building of relationships, the sharing and critical scrutiny of deep knowledge, and traversing the edge of chaos while seeking coherence.

The nine ideas for becoming change savvy are intended to first loosen up your thinking about the phenomenon of change, and then as a set to help you focus more realistically—more humanly—on the phenomenon of change. Now that we have an appreciation of the process of change, we can turn to more details. One of the most powerful and complex variables involves the role of teams and groups. We have some great new insights, for example, about autonomy and collaboration. Almost everyone agrees that “relationships” are key, but they seem to leave it as a truism. It is time we delved into its deeper and more specific meaning when it comes to the dynamics of change.