5

Discovery II: Get Ready, Get Set …

We’re done with paperwork for a while now. The second part of discovery involves what lean practitioners call “getting out of the building,” which means breaking the Plan–Fund–Do cycle by going directly to your targets (or customers, clients, funders …). The core of discovery is testing your guesses with real people. In the next chapter, you’ll test the “problem” hypotheses in your value proposition to make sure you understand what it is you’re trying to change and how your targets themselves see the problem. Then you’ll test your vision and the solutions you are proposing. But before you actually “get out of the building,” you’ll need to take some key preparatory steps to make sure you effectively encounter the people you hope will join you in making change happen.

Key Ingredients!

The process of discovery is one of radical doubt—you don’t believe your guesses until you have validated them with customers. The lean startup is about a decade old as a practice in business, and in that time a few truisms have emerged that help practitioners be both visionary and grounded.

Honor Your Vision

You are starting a phase of direct contact with the world, with your targets, with those you hope to affect. There will be no shortage of naysayers and negative feedback if you are proposing true innovation. Know that by using the principles of the lean startup, you are giving your innovation the best shot at success, whether or not your initial formulation proves correct. Be ready to hear hard answers and to get useful feedback. Then remember that all of these are in the interest of giving your first impulse for change the best possible chance for success.

“No Plan Survives First Contact with Customers”

This truism from the private sector holds for the social sector as well. Your initial hypotheses and ideas about how the world worked as you envisioned it in the canvas are rarely right. Remember how the Homeless Services Center’s first efforts focused on building community collaboration? It turned out that what was important was to focus on the amount of time each step toward a home was taking. It felt good to have disparate organizations helping each other out, but it wasn’t the critical piece for solving the problem.

It’s best to start with radical naivete, or what Buddhists call “beginner’s mind.” Don’t be shy about asking questions about the problem or your proposed solutions. But be prepared to hear anything, and then to pivot to a new set of hypotheses based on your interviews.

Sometimes People Don’t Know What They Need

As much as you should be listening to the people you will be interviewing, you may be exploring the creation of something that very few people understand at first. This truism comes from innovators as diverse as Steve Jobs (who once said, “A lot of times, people don’t know what they want until you show it to them”) and Paolo Freire (who built an entire theory around false consciousness and how people could embody the idea of their own oppression).

There is nothing elitist or unreasonable about innovation, about creating things that no one has seen before. So listen well during this discovery phase and gather evidence, but keep faith with your innovation until the conversations and hypothesis tests you’ve run tell you to shift direction. That too will undoubtedly happen on your way to success.

You Need External Advice

Separate from the interviews that will constitute the core data for your hypothesis test, get some advice about your canvas and your hypotheses from some outside experts. Talk to at least two types of people—those who have tried to do something similar, and those whom you believe are likely to be “early adopters” of your innovation because they share so much of the same worldview. Explain that you will be testing hypotheses with a broad array of targets, “customers” and/or stakeholders, and have them take a critical look at the hypotheses you’ve generated so far. Whom do they recommend you speak with? What kinds of tests would they run on these hypotheses? Can they think of other hypotheses that you haven’t thought of yet? Take all this great input to shorten the path to effective interviews in these two steps.

Identify/Review Big Risks

Do a gut check on where the biggest risks are for your innovation. What elements of your innovation make you most nervous?

Work from Falsifiable Propositions/Hypotheses

Your canvas has a number of hypotheses on it. As you work (usually from right to left across the canvas), think about how each hypothesis can be tested simply, resulting in a yes/no answer.

In the New York City Toilet Bowl Retrofit Program, for example, a major hypothesis was that plumbers would be willing to do retrofits. We could have asked plumbers unions and large contractors if they were interested, but a better test was to ask whether they would routinely conduct retrofits for $200 (or whatever price we thought was appropriate).

Even better would have been to put out a (nonbinding) Request for Inquiries (RFI) and to measure how many inquiries we got. Best practice today would be to put the RFI out online and measure the response rate at different price points (at $50, $100, and $200, for example).

Keep the Team Compact

You want to test your early hypotheses with a small team for a couple of reasons. First, you can’t really outsource the kind of insight-gathering you’re about to do. Your vision, your team’s vision, must be tested by you, communicated as well and as directly as you can. And the feedback needs to come back to the source of the innovation—you—to effectively help the team learn.

The second reason for a compact team is that it is increasingly easy to test your hypotheses, so the leaner you can stay until you know the right direction the better. Staying lean in this phase means you can stay focused on learning and avoid building a team too early that may not fit where your innovation is headed. Your initial vision may, for example, be to build a strong door-to-door canvassing organization. After a few weeks of interviews and field-testing it may turn out that you’ll be far more effective on the phone and that the early hiring of a canvassing expert leaves your effort with too much skill in one arena (canvassing) and too little where it counts (phone banking).

Finally, the sooner you figure out how to gather data cheaply the better off you’ll be. One of the major frameworks of the lean startup is innovation accounting, a measure of how quickly you are actually innovating. We’ll cover it more in chapter 11, but the more efficiently you can test, the quicker you’ll learn and grow.

This bias toward lean-ness is increasingly pervasive in the private sector because of how many low-cost tools exist today for testing hypotheses. New companies today often need to demonstrate large-scale customer behaviors before they can raise any money from investors. Early investment in social sector innovation sometimes requires a lower threshold for hypothesis testing, but why spend a lot of money before you have at least an initial working model? Part of the idea behind the lean startup is to use scarce social sector resources more efficiently. Proving out your innovation in as lean a way as possible is the best way to do that.

Communicate

The lean startup needs you and all your partners in innovation (funders, bosses, boards, community members …) to be open to the hard data that the discovery phase will generate. Regular communication about your hypothesis testing and your results will be critical to building a team that’s ready to build, measure, learn, and pivot its way to unprecedented success.

Quality and Quantity

You will usually start with qualitative research (interviews and observation) about your hypotheses and then move on to testing your hypotheses with larger and larger numbers of targets. The important thing is to value both types of research. Insights from real discussions with real people are the most important, but they also have to start panning out in simpler interactions with more and more people. If your hypotheses aren’t sustained when you start testing them quantitatively, it’s time to regroup and find the paths forward that scale appropriately.

Early Evangelists

Some people will understand what you’re about right away and love it. They are your most important targets, the people who somehow epitomize the problem you’re trying to solve and the exact way you framed your solution. Spend a lot of time understanding what makes these folks true believers and what shapes their world. They will provide you with critical data for the first three stages of customer development.

Don’t Let These Reasons Stop You!

Let’s face it … it’s hard to talk to people. And it’s even harder to have to listen to them not quite get your big idea. As teams prepare to “get out of the building” the darnedest reasons not to do so always seem to come up. To help inoculate you against this problem, here are some of the most common reasons for not interviewing people that we’ve heard over and over again. Read them here so you can dismiss them and move forward:

• “We can’t talk to enough people to be statistically significant!” Yes. That’s the point. Nobody understands what you’re doing yet, so getting a lot of them to listen could be hard. Try to get ten of them to agree with you and you’ll be making progress. Another part of this objection is the focus on statistics, which are very important once you do start getting people to pay attention to your innovation. But until then, interviews give you rich details about why they aren’t getting it, about what’s not quite right for them, and about what makes them really interested.

• “The foundation already approved the grant.” Sometimes you’ve already convinced a key target, a funder. Congratulations, but you owe it to yourself and the social problem you are taking on to give your innovation the best possible chance. Get out and talk to the people you are trying to serve so you can use the grant to the greatest effect.

• “This is so obvious!” Then your interviews will be short, but don’t take it for granted that people just a little outside your inner circle may not think things are so clear. If they do, you’ll move into implementation very quickly.

• “We’ll lose the element of surprise.” The most fundamental aspect of lean is learning, and worrying about the tradeoff between surprise and learning almost inevitably stifles the learning and increases the negative surprises. And, as you’ll see in the next section, you start by validating the problem, which doesn’t reveal the solution to your early interviewees. You can be more selective with those you interview in the third step, the solution interviews.

• “I don’t want to raise expectations.” Sometimes, particularly in government, there’s a fear that mentioning an innovation will create a demand that can’t be met. This is usually in the category of problems you want to have. If there’s that much demand, structure your interviews to document it and your odds of funding and adoption can only go up.

Be Ready for Success

Every once in a while, things come together and your innovation starts to take off beyond even your wildest dreams (for example, see the story of the Kony 2012 campaign in chapter 6). Take just a little time to plan how to handle expansion if your dreams come true.

Key Techniques for Outside the Building

The rest of discovery is about fearlessly testing your understanding of the problem and the key elements of your solution and then pivoting toward a product or service that definitively hits the mark. You do this testing by getting out and speaking with lots and lots of people. As your understanding grows, you can also use the Internet to test with more and more people, and in the process grow the list of early targets so vital to the next stages of customer development.

Interviewing is the core technique of the testing phase of discovery, and you can break the interview task in each step into three components.

1. Reach a Large Number of Interviewees

Generally, you and your team should aim to reach at least fifty people for each step. This is real work and, if you’re lucky, will result in twenty to thirty in-depth interviews.

To get to this many people, start with the people you know and expand outward. Speak with direct targets (the people your product or service will interact with the most), with indirect targets (people you hope to reach through your direct targets), and with funders. You may find, with the latter group, that they are rarely approached for their view of problems and that they will welcome the chance to share how they see the space. You can further build the list by asking your first-level contacts for additional referrals (“Anyone else you know who works in this area/has this problem?”), cold-calling relevant people, and using social networks like LinkedIn or Facebook. Finally, develop a short script that gives your prospective interviewees a capsule understanding of what you are seeking to understand, and what they can hope to get out of taking the time to speak with you.

2. Conduct Effective Interviews

The key is to speak much less than you listen, and the most basic element of this is to ask open-ended questions (ones to which you can’t answer yes or no). Rather than “Do you think you get too much junk mail?,” ask “How much junk mail do you get?”, or even “How do you feel about the different types of mail you get?” Beyond that, prepare a simple script that each member of your team follows to help with consistency in aggregating your results. Make sure your script leads your interviewee into an open discussion, that you capture key demographic information, that you tell a story that frames the interview, that you get key information about the environments they operate in (Who’s the funding decision-maker? Where do they normally encounter this problem?, and so on), and that you or (preferably) a listening partner keep track of the data coming in with respect to your hypotheses.

There are two steps to take late in the interviews. First, after you’ve gotten good answers to open-ended questions, sometimes you can circle back around to your most basic hypotheses with very direct questions, like the “Do you get too much junk mail?” question above. Second, never miss the chance to learn more about the “environment” you’re innovating into. Find out what else your targets do: their favorite museums, where they normally shop, whom they depend on for the best information. Use this as a chance to find out good metrics, too. Ask them who they know who’s excellent in the space you’re addressing, and what makes those people excellent. You can revisit these notes as you move into implementation and use them to set benchmarks for your own organization’s performance.

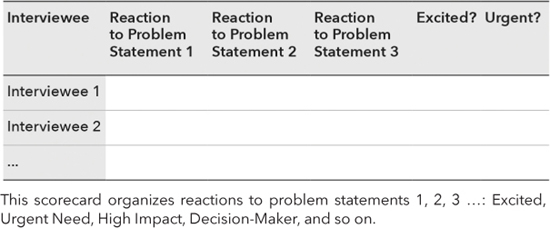

3. Score or Evaluate the Interviews

Simple or complex, come up with the right scorecard for your particular customer development hypotheses and process. Figure 5.1 is a tool for doing this. Fill in the top row with things you want to measure and put each interviewee on one row. This grid will let you see which of your measures got the most positive (or negative) feedback in one place and can help you understand the spread (or diversity) of reactions to your innovation.

Online Testing and the Minimum Viable Product

Although not always possible, using online tools is another core technique to test the problem and the solution. In the early phases of an online approach, you run very simple online tests, like posting a webpage or a short video explaining the problem, then the solution, and then interviewing (by phone or in person) people who visit. But online testing is a vast world today, and it is not uncommon for online startups in the for-profit world to run, with very few resources, dozens of tests a day once they start getting even very initial traction. In the social sector, this technique is most commonly found among political organizations in the runup to elections.

Figure 5.1 Interview Scorecard

In lean practice, you use a minimum viable product to test both your problem hypotheses and your solution hypotheses. This is a very important concept with multiple variants, and we’ll cover it in more depth in chapter 6.

Lean startups use customer development because that’s how you ground-truth your guesses … with the people you hope to influence, to serve, to raise money from, to inspire. It’s time to meet them … first contact!