12

Institutionalization: Building the Lean Organization

The fastest-growing nonprofit I ever served actually grew too fast. Big Think started with a small fellowship to Bill, its founder and one of the greatest social innovators I have ever known.1 His idea was to change the way Americans thought about the future, to redirect our national energy toward more positive outcomes. Within a year, he had written a concept paper, recruited some incredible senior researchers, raised several hundred thousand dollars from a handful of individual donors, and scored the cover article of a national magazine.

The one metric that mattered was common for think-tanks—getting mentioned in the press. And by any measure, Big Think was swinging way above its weight class.

Within two years its budget had grown to over $2 million a year, collected from a small group of very big donors and a growing set of national foundations. Big Think had some of the country’s most innovative thinkers and a superb writer/director of publications who regularly landed major articles in national magazines.

Bill had a great instinct for media and an even greater one for donors. He had identified a solution—big new ideas for our country disseminated in mainstream news publications—and he had a pitch that foundation boards and wealthy individuals found compelling. He had a solution hypothesis that resonated with two critical targets: the mainstream media and wealthy individuals.

Toward the end of our second year in business, I had flown out for what I thought would be a routine board meeting. We arrived and the chair immediately convened an executive session to let us know that there was basically a staff revolt underway—unless we fired Bill, the staff would all resign. We all looked at each other and started wondering what had happened.

Building a Lasting, Lean Organization

The rise of Big Think was actually a wonderful case study in the first three stages of customer development. Through extensive discussions with donors (his most important target) and journalists, Bill had done discovery and found a solution for a problem that a lot of people had—a new think-tank focused on generating innovative ideas and pushing them into mainstream media. He had validated that solution by achieving astonishing success at placing stories and at getting, keeping, and growing media attention. He’d been able to create real demand for the model and to replicate and expand on the initial success.

The only problem was where to stop. The question even Bill’s most ardent supporters were asking was “What does Big Think not do?” Having created an innovative solution for generating new ideas, Big Think, under Bill’s ambitious leadership, was expanding beyond its think-tank role. Rather than turning his attention to institutionalizing this solution, Bill continued to propose new spheres of activity, like political organizing and lobbying, that left the core staff and some of the initial donors with serious doubts about Big Think’s ability to execute on its original innovative mission.

The Organizational Evolution of Innovation

For the first two years, Big Think had been searching for a sustainable business model—and it had found one. At that stage, a different type of innovation is required, the innovation to build an institution that can focus and deliver the solution at as large a scale as possible.

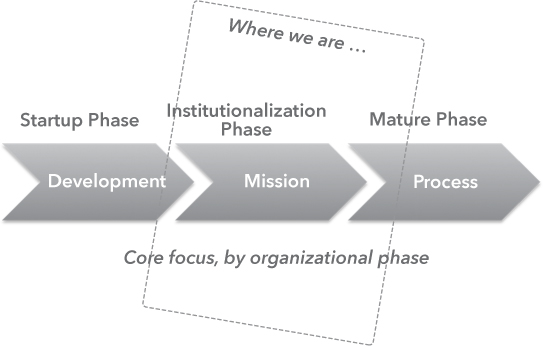

Steve Blank points out that a successful innovation goes through three phases on its way to deployment as a mature and large-scale solution (see Figure 12.1). Most of this book has been focused on the first phase—development, the experimental process of discovery, validation, and creation covered in chapters 4 through 11. At the other extreme, once an innovation is scaled and fully deployed within a large institution the core energy is focused on creating replicable processes to reliably deliver the solution.

The end of the creation phase is the time to scale and build an organization around your innovation. You’ve proven it solves a problem and you know how to get, keep, and grow the people and institutions that use it. What’s left is to move from rolling out a series of experiments to rolling out an organization to deliver your innovation to the world and to grow it to have the biggest impact possible.

The focus of the institutionalization phase is to codify the wisdom and direction from the development phase into a mission that embodies the endpoints you now understand while leaving room for innovation in how to reach them. This process holds for organizations that start from scratch as well as for innovations incubated and retained within existing organizations. Whether you’re standing on your own or scaling up within another, bigger organization, when you complete this phase, you won’t be a startup anymore.

Figure 12.1 Organizational Phases

For social sector innovation to have vast impact, the institutionalization of that innovation has to focus on four critical activities:

1. Growing the base of targets (direct, indirect, and funding) so that your impact can grow and be financially viable at scale.

2. Building an organization and management structure appropriate to your mission.

3. Hiring the right people for the right jobs.

4. Creating a lasting culture of innovation.

Growing the Base: From Early Adopters to the Mainstream

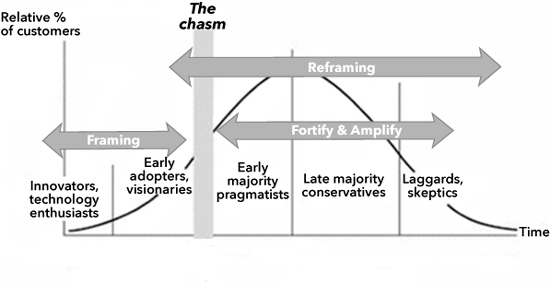

How you will grow your impact depends a great deal on the organization type you determined in the creation phase. Figure 12.2 revisits Moore’s famous chasm diagram with three key positions superimposed. If your innovation needs to introduce a completely new frame to a new population, you shouldn’t build an organization geared to a lot of people yet. Most of the work will be around reaching early adopters and converting them to your new frame.

On the other hand, if your innovation fortifies and amplifies an existing solution that is well understood by your target populations (for example, doing a better job of making consumers aware of the environmental impact of shopping), then you’re in the linear part of the growth curve (Moore’s Early Majority). You can focus on quantity over quality, pushing your solution into more and more of the mainstream set of adopters on the righthand side of the curve.

Big Think had been a classic framing innovation and had achieved astonishing momentum among visionary donors, journalists, and citizens. The challenge Bill started to face was how to set up for long-term scale. After all, if the idea was to get new ideas into American politics it wasn’t enough to simply have early adopters like these ideas. They had to eventually cross over to something like a majority of voters or at least policy-makers.

Figure 12. 2 The Chasm and Organizational Strategy/Position

The complaint voiced by staff was that Bill was trying to be all things to all people. As one person put it, “We don’t know what we are not!” Bill kept promising a broader set of innovations to a broader set of donors, terrifying staff about how they could be expected to deliver on such a wide array of expectations.

Bill committed the classic error of early success—he assumed that he could continue to grow the way he had in the early stages of the organization. Instead of evolving strategies to reach an early majority, he continued to pump out visionary ideas that excited his early adopters. Since they “got” things quickly, they also potentially got bored quickly unless he renewed their interest with another bright, shiny object.

In fact, there are two classic ways to cross the chasm, and Big Think hadn’t planned for either one. The first (and most popular) is to focus all your resources on getting traction among a small number of people in the early majority. Remember the Smarter, Cleaner, Stronger campaign? The singular focus there was on a small subset of the business sector (the business columnists on editorial boards) in each state. We hoped from there to go to businesspeople, and from those to senators.

The second approach is to build the early adopter base large enough that it tips over into the early majority through sheer numbers. To do that, Big Think would have had to become something like a membership organization, or at least to spend significant time and energy getting, keeping, and growing a base of people who promoted its agenda.

Figure 12.2 suggests the kinds of targets you will be engaging based on where in the adoption cycle (from early adopters to laggards) your innovation is aiming. Your hypotheses about growth should reflect the type you’ve chosen with respect to your targets. If your innovation truly frames something new, you can expect rapid growth among early adopters but slow growth in the mainstream until you’ve “crossed over.” For Big Think, this looked like a lot of press for its ideas in alternative media with much slower adoption by mainstream media outlets. Its hypotheses about expanding its base needed to be clear about defining the numerical goals it planned on hitting among early adopters, distinct from those targeting mainstream media and funders. The rates would be quite different.

If, on the other hand, you’re fortifying and amplifying, then you’re seeking to grow your innovation within an existing base of targets who already understand the problem and solution. In that situation, you might hypothesize linear growth within the existing mainstream population. For example, the National Museum for the American Indian tapped existing museum-goers and aimed to capture a linearly growing percentage of visitors to the Washington museum scene.

Overall, remember your lean roots and build an organization that has an eye for hypotheses and data that can confirm or reject your ideas about what will work organizationally to increase your impact over the long term.

Organizational Development and Management: Forming Mission-Driven Departments

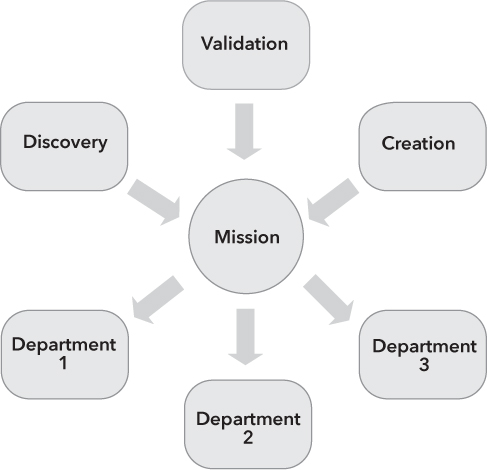

The second part of institutionalization is determining the optimal organizational structure for your innovation’s growth. This structure can be stand-alone, if your innovation started on its own, independent of other entities, but the structure can be within an existing organization if the innovation was incubated within one. The structure should flow from a mission that’s emerged from all the steps you’ve taken to date and then embed key elements of that mission in each of the structure’s components or pieces.

Mission

You already understand your mission. Until this stage, it has been a concise summary of the problem you identified and the solution you developed. Remember that you’ve gotten this far because you’ve stayed focused, you’ve tested your ideas with lots of people in real-world settings, and you’ve shown that you’ve got an innovation that works.

For far too many in the social sector, developing an organizational mission (or purpose) feels like a difficult, conflict-laden task. In the vast majority of cases, by the time your team and your board are assembled in one place to determine a mission, it’s because you all fundamentally agree on a common mission already. (Real disagreements typically stem not from how you’ve defined the mission, but from the nitty-gritty details of how to allocate funding, what do to first, in what time frame, with which partners, and so forth.)

Figure 12.3 Mission’s Role in Structure

Remember: Your mission is already a concise summary of your problem/solution pair. To grow your organization, you can add to the mission some of the other operational hypotheses you’ve proven, including the activities that represent your growth hypothesis and key metrics generated from the validation and creation phases. Not all of these need to make it into the outward-facing mission statement, but they should be well explained in the mission statement used day to day in operating the organization and, ideally, in communicating to your funders.

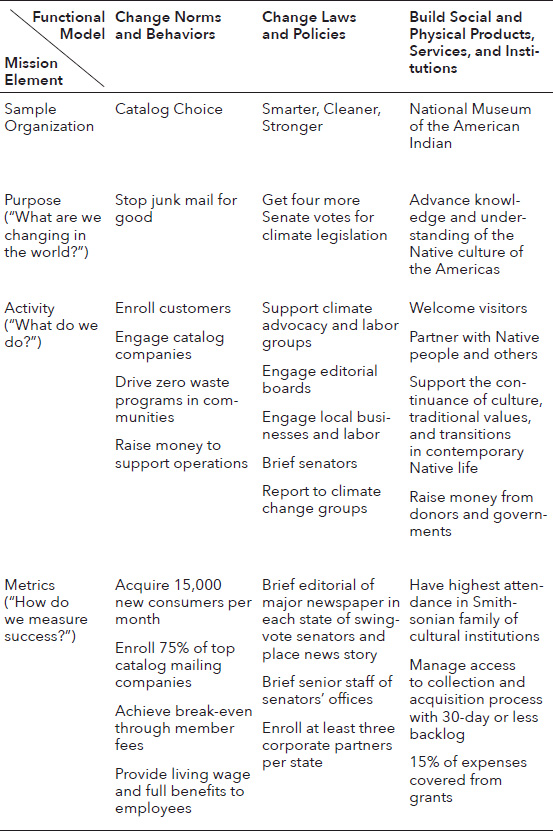

The fleshed-out, full mission statement should still be concise, but also detailed enough that new employees can read it and know what they are there to do. Table 12.1 shows some samples.

Departments

Your operational mission should be the basis for an organizational structure to grow your innovation to full scale. In the validation and creation phases you built a repeatable and scalable process that built your innovation. Now is the time to embody that process within departments.

The kind of departments you form will depend on the nature of your innovation as well as what function and position you’ve adopted. Group the activities from your overall mission statement (derived from your experiences in the prior phases). Your functional position (Norms/Behaviors, Laws/Policies, Social and Physical Products and Services/Institutions) should guide this choice, since different types of organizational functions require different types of departments and employees.

Each department in turn has its own mission statement that specifies its purpose, activities, and metrics. These statements are far from generic but must depend instead on the specific learning you’ve amassed to date about the optimal organizational types for your innovation and where you are with respect to your targets. Framing innovations need to focus a lot on explaining the innovation to populations that may never have seen anything like it and convincing a smaller number of early adopters. Fortifying/amplifying innovations, on the other hand, will probably focus on reaching as many people as possible with an innovation that already fits their worldview.

Table 12.1 Activities Linked to Missions

One of the most critical tasks of the institutionalization phase is to continue to monitor your relationship to your targets along the lines you tested in the creation phase. How big is the gap between the people your innovation is reaching today (early adopters) and the early majority beneficiaries? If you are driving an innovation that fits into how people understand the world today, you’ll probably want to start scaling. If, on the other hand, you’re trying something pretty new (like putting homeless people into permanent houses), your energy will focus less on sheer numbers and more on building a loyal, early base of people who “get” your solution and can help it spread.

As important as the departments you build in this phase are the people you fill them with.

The Right People for the Right Jobs

Hiring the team that will take your innovation to scale is probably the single most important activity you will undertake from here on out. Your success will very likely depend on two factors: the extent to which you’ve structured the jobs in your organization to meet the mission and the quality and “fit” of the people you hire for those jobs.

Carefully consider the positions you are trying to fill so that they are related to the organization’s overall type. There is a big difference between a fundraising director for a startup with a framing position (pushing an idea that’s new to the world) and one for a startup that’s seeking to convert existing members of a parent organization to a new way of seeing a similar issue. Match the experience to your organization type and the jobs that need to be done to fulfill the mission.

The final key to institutionalizing your innovation is to build creativity and innovation itself into the organization.

A Lasting Culture of Innovation

Remember how the social sector is the sector in which we so often cannot afford to fail? The problems we address aren’t always easy to solve, but they often require us to try no matter what. This moral imperative is a remarkable source of innovation in our sector, as well as a remarkable source of the diversity of ideas people have about how to solve problems.

Rather than try to catalog all the paths to innovation, this section focuses on the three meta-components to creating a culture of innovation: innovation accounting, decentralized leadership, and mission clarity.

Innovation Accounting

We discussed innovation accounting in the discovery phase as a way to husband resources. By accelerating the speed of hypothesis testing and decreasing its cost, a startup nonprofit or government project can buy time for more pivots, for more honing of the solution to make it truly game-changing.

Innovation accounting is equally important as your solution gets embedded in a larger, well-established organization. What systems can you put in place that keep you and your team abreast of new developments among your targets, your supporters, key allies? What is an appropriate, ongoing measure of innovative activity?

Many elements of lean practice originated in Japan’s automobile industry, but the recent rise of principles of lean startup owes at least as much to the success it’s had among software startup companies. While larger companies like General Electric and Intuit are starting to follow suit, not many mature (or at least middle-aged) social sector organizations have adopted lean practices at scale.

Good innovation accounting practices have one thing in common: they focus on improving rates, not on increasing absolute numbers. In the discovery phase, the innovation metric was not the number of total tests run, but rather the rate at which the number of tests was increasing. The activities of a specific department may well be measured by “making the numbers”—achieving key numerical outcomes. But the measure of innovation within departments should be the rate at which the targets themselves are improving. If the department isn’t innovating, it’s not the end of the world—it will still be reaching great penetration in its target populations. Sooner or later, however, the department will run into a challenge or a ceiling limiting how high it can go.

A department that is achieving and innovating will be spending some of its energy on raising its sights to ever higher targets, and the measure of that innovation will be a steady or accelerating increase in the targets themselves. Intuit, one of Silicon Valley’s most innovative companies, provides a look at this principle in action.

There are not many “grandparent” companies in Silicon Valley, but Intuit would have to be counted among them. Founded in 1983 and facing intense direct competition from Microsoft for most of the 1990s, Intuit has survived and thrived by innovating throughout its history. Intuit manages innovation by having a distinct innovation pipeline, where each product is rated based on where it is on the experiment-versus-institutionalize spectrum (which Intuit calls the Horizon Planning System). Intuit’s metrics for innovation follow the rate-of-rates principle. It seeks to drive continuous improvement in two key performance indicators:

1. How many customers are using products that didn’t exist three years ago?

2. How much revenue is coming from products that didn’t exist three years ago?

As Eric Ries reported in The Lean Startup, Intuit was able to shorten the time it took to reach a threshold of $50 million per year in revenue from 5.5 years to less than twelve months. This focus on accelerating the rate of innovation (that is, changing the rate of the rate) is a prime example of true innovation accounting.

Leadership

The practice of the lean startup owes quite a bit to the invention of lean manufacturing in the Japanese auto industry in the 1950s. Faced with US competitors that had seemingly endless access to capital, Toyota had to find a way to be as productive with far less equipment. Toyota realized that it needed to rely on innovation and continuous improvement and turned instead to the wisdom of its workers on the shop floor. The company is largely managed by these principles to this day.

For innovation to take root in social sector organizations, there needs to be a similar commitment to decentralized learning and leadership. The entire customer development cycle is based on the learning achieved through direct contact with targets and beneficiaries of social sector innovation. Leadership must emanate up from that customer-centric view, from the ground up, and every team member must understand and be attuned to the broader mission.

Innovation is born from a leadership structure that recognizes that the data for innovation relies on the people you serve/customers, and that every customer-facing employee is therefore leading innovation for the organization. By being clear on the mission and key activities, organizations can empower their own people to accelerate innovation.

Mission Clarity and Transparency

Earlier in this chapter we discussed how critical it is to develop a mission statement that clearly embodies what the organization is about. For innovation’s sake, the important thing is how the organization drives clarity and transparency in its practice.

Clarity and transparency of the mission is critical for at least three reasons. First, innovation needs to be part of each employee’s job, and each employee needs to own the overall mission to be able to contribute to its improvement. Second, true mission transparency keeps different departments in communication and allows cross-organizational innovation. This transparency is particularly important, for example, in fundraising. Imagine, a year out, that a set of grant-makers shifts priorities and reduces the overall funding available to your innovation.

This is not the fundraising department’s fault, so while that department has to figure out some alternatives, the operational side of the organization must adjust its expenses downward. There may be departmental separation, but the organization as a whole has to innovate its way out of the funding crunch and will be far more likely to do that if the mission is understood fully as being achieved across departments. Finally, mission clarity and transparency are part and parcel of having crisp metrics that help people understand their goals and excel beyond them.

Innovating within an Existing Organization

Can established, mature organizations use lean startup techniques? This book was written for innovators both inside and outside traditional social sector organizations, but some key issues do arise when you’re trying to run lean within a mature enterprise.

There are major operational differences between developing an innovation and operating an institutionalized program or service. Figure 12.1 showed how the core energy of more mature organizations is focused less on development/experimentation and more on mission and, eventually, process. Innovation is always valuable, but there are legitimate reasons to be nervous if that innovation has to operate side by side with mature, well-established departments and service delivery units. Some examples:

• A fundraising department experimenting with the shift from direct mail to online giving may worry about disrupting existing fundraising channels and reducing overall revenue.

• A hospital experimenting with placing outpatient clinics closer to residential areas may legitimately worry that having fewer intakes at the main hospital may lead to lower core revenue.

• An environmental organization may worry about confusing its constituents if it shifts its campaigns against pollution from a health focus to an economic focus.

These examples and countless others illustrate the need to experiment with evolving the mainstream organization’s approach for greater success (or to respond to changing conditions) while preserving its present, proven performance. The key is to recognize both the need to constantly innovate and the legitimacy of protecting the status quo. If you can do that, it becomes a lot easier to keep the overall organization fresh while minimally threatening the stability of its existing operations.

There are a few ingredients to fostering a rich innovation environment within a more mature organization. First, the leadership and as much of the rest of the organization as possible need to explicitly recognize that failure is intrinsic to the parts of the organization that are doing the lean startup and developing innovative initiatives. Without a tolerance for failure (which in the mature parts of the organization would be a signal that things were going quite wrong), the innovation team won’t even get off the ground. Leadership needs to decouple traditional mission and process metrics to focus on the learning that the innovation team is meant to generate. Wherever possible, this acceptance of failure must also be communicated to donors, grantors, and other funders.

Another key ingredient is increased communication between the innovation units and the rest of the organization. Drawing the whole organization into the failure and successes of those units will maximize acceptance, enable them to share key learning, and ensure that the parent organization is well equipped to deploy the innovations as they mature and become ready for institutionalization.

Finally, mature organizations should consider creating innovation sandboxes—separate departments, sometimes even located offsite, that are free to develop their own culture, staffing, budgeting, and fundraising appropriate to the innovations they are developing in the parent organization’s name. A bit of separation and autonomy can insulate the core organization while fostering the experimental context needed to break through to higher levels.

What to Watch Out for Now That You’ve Made It: Execution and Environmental Risk

You’ve successfully institutionalized your innovation when you have an operating model that’s scaling your impact, you have a mission and an organization that reflects that mission fully, and you’ve built a culture of innovation to ensure that you continue to expand your impact well into the future. This stage represents a transition from Build-Measure-Learn to driving a clear mission and, eventually, rigorous processes for ongoing results. After surviving the arduous path of customer development, what’s left to worry about?

The leaders of any social sector organization will tell you: lots. Running any organization that’s trying to drive change into the world is challenging, not least because often a lot of change is needed on really pressing problems. As seen through the lens of the lean startup, though, a few big challenges stand out from the host of day-to-day issues.

First, as you may have noted, the institutionalization phase puts less emphasis on agility—there’s less “build–measure–learn” and more “build and operate.” This is largely because, by the time you’ve gotten through the creation phase you’re armed with proven strategies for delivering your innovation at scale. Even so, the risk remains that you haven’t gotten it quite right, or that there is an even better way to drive change, so your entire team needs to be regularly engaged in making sure your organization is positioned for maximum impact.

The risk inherent in executing your innovation lies in how you assemble, operate, monitor, and hire into your organization. Pivoting is a lot harder when you’re institutionalized, but adjusting missions, department structures, staffing, and metrics all have to be part of driving higher performance in the service of your solution.

The other major risk you face in institutionalization is environmental risk along at least two lines. The first, just outside the formal boundaries of your organization, is a series of stakeholders you don’t control. These include board members, funders, competitors, enemies, and key partners. You’ve engaged some of them as part of the customer development process, but it will be important as you mature to make sure they are part of your ongoing innovation practice. The lean startup radically speeds learning in organizations, and you need to find a way to keep people who aren’t involved on a daily basis engaged in this learning. For board members, ensure that they understand not just your mission but the customer development process itself. For your enemies, make sure someone is watching them throughout your organizational development and suggesting ways you can tweak it to continue to drive change despite opposition.

For funders, oversight entities, partners, and others even further outside the organization, you will have to measure how much to share. At this stage, you are through the major pivots so you will be able to present a pretty stable set of goals and metrics to these external constituencies. Your choices will continue to be informed (more than most in the social sector are used to) by the truth that only close contact with customers, targets, and constituents can provide. This ground truth can be a powerful tool for engaging the external constituencies you most need to stay close to, but they need to be with you for the positive as well as the negative surprises that will ensue from your success.

The second environmental risk is simply the broader social, political, and economic context in which your innovation is operating. This context has been a variable throughout the customer development process, and by following that process not only did you take it into account, but you’re also far better prepared to continue to respond to changes in your operating environment as they arise. As you institutionalize, your organization must keep on top of these environmental variables and be prepared to take advantage of those that are favorable and adapt to or defend against those that are not.

An Institution

At the outset of this book, we discussed how the world is, in many ways, changing faster than ever before. The social sector is on the front line for the disruptions wrought by change. By reaching the institutionalization phase of customer development, your innovation and your work have made it a better front line.

You started with the courage to make change, and it takes courage to get this far: the courage to listen to data as it crashes into your dreams, the courage to adapt to what very real people—your customers, your partners, your targets, your funders—show you after you show them that initial dream. The courage to go beyond simple numbers and to understand how to bend the curves and shape the rates that can push you to greater impact. The courage to build an institution that follows the formula you discovered, that holds itself accountable for ongoing innovation, and that is promoting change for the better in a world that sorely needs it.

Congratulations! You’re not a startup anymore.