Chapter 7. Integrating Lean UX and Agile

Agile methods are now mainstream. At the same time, thanks to the huge success of products such as the Kindle and the iPhone, so is user experience design. But making Agile work with UX has long been a challenge. In this chapter, I review how Lean UX methods can fit within the most popular flavor of Agile—the Scrum process—and discuss how blending Lean UX and Agile can create a more productive team and a more collaborative process. I’ll cover:

- Definition of terms

Just to make sure we’re all on the same page about certain words like “sprint” and “story.”

- Staggered sprints

The one-time savior of Agile/UX integration is now just a stepping stone to true team cohesion.

- Listening to Scrum’s rhythms

The meeting cadences of Scrum are clear guideposts for Lean UX integration.

- Participation

A truly cross-functional process requires that everyone be a part of it.

- Design as a team sport

Ensuring that the once-closed design process is now open to all team members is key to your success.

- Managing up and out

Clear obstacles to your team’s progress by being proactive with your communication.

Some Definitions

Agile processes, including Scrum, use many proprietary terms. Over time, many of these terms have taken on a life of their own. To ensure that I’m using them clearly, I’ve taken the time to define a few of them here (If you’re familiar with Scrum, you can skip this section.)

- Scrum

An agile methodology promoting time-boxed cycles, team self-organization, and high team accountability. Scrum is the most popular form of Agile.

- User story

The smallest unit of work expressed as a benefit to the end user. Typical user stories are written using the following syntax:

As a [user type]

I want to [accomplish something]

So that [some benefit happens]

- Backlog

A prioritized list of user stories. The backlog is the most powerful project management tool in Agile. It is through the active grooming of the backlog that the team manages their daily workload and refocuses their efforts based on incoming knowledge. It is how the team stays agile.

- Sprint:

A single team cycle. The goal of each sprint is to deliver working software. Most Scrum teams work in two-week sprints.

- Stand-up:

A daily short team meeting at which each member addresses the day’s challenges—one of Scrum’s self-accountability tools. Each member must declare to all teammates, every day, what he or she is doing and what’s getting in his or her way.

- Retrospective

A meeting at the end of each sprint that takes an honest look at what went well, what went poorly, and how the team will try to improve the process in the next sprint. Your process is as iterative as your product. Retrospectives give your team the chance to optimize your process with every sprint.

- Iteration planning meeting

A meeting at the beginning of each sprint at which the team plans the upcoming sprint. Sometimes this meeting includes estimation and story gathering. This is the meeting that determines the initial prioritization of the backlog.

Beyond Staggered Sprints

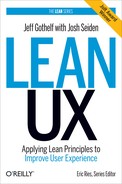

In May 2007, Desiree Sy and Lynn Miller published “Adapting Usability Investigations for Agile User-centered Design” in the Journal of Usability Studies (http://www.upassoc.org/upa_publications/jus/2007may/agile-ucd.pdf). Sy and Miller were some of the first people to try to combine Agile and UX, and many of us were excited by the solutions they were proposing. In the article, Sy and Miller describe in detail their idea of a productive integration of Agile and user-centered design. They use a technique called Cycle 0 (you may have heard it called “Sprint Zero” or “Staggered Sprints” as well).

In short, Sy and Miller describe a process in which design activity takes place one sprint ahead of development (Figure 7-1). Work is designed and validated during the “design sprint” and then passed off into the development stream to be implemented during the development sprint.

Many teams have misinterpreted this model. Sy and Miller always advocated strong collaboration between designers and developers during both the design and development sprints. Many teams have missed this critical point and have instead created workflows in which designers and developers communicate by handoff, creating a kind of mini-waterfall process.

Staggered sprints can work well for some teams. If your development environment does not allow for frequent releases (for example, you work on packaged software, or embedded software, or deliver software to an environment in which continuous deployment is difficult or impossible), the premium on getting the design right is higher. In these cases, Lean UX may not be a great fit for your team, as you’ll have to work hard to get the market feedback you need to make many of these techniques work.

For these teams, staggered sprints can allow for more validation of design work—provided that you are still working in a very collaborative manner. And teams transitioning from Waterfall to Agile can benefit from working this way as well, because it teaches you to work in shorter cycles and to divide your work into sequential pieces.

However, this model works best as a transition. It is not where you want your team to end up. Here’s why: it becomes very easy to create a situation in which the entire team is never working on the same thing at the same time. You never realize the benefits of cross-functional collaboration because the different disciplines are focused on different things. Without that collaboration, you don’t build shared understanding, so you end up relying heavily on documentation and handoffs for communication.

There’s another reason this process is less than ideal: it can create unnecessary waste. You waste time creating documentation to describe what happened during the design sprints. And if developers haven’t participated in the design sprint, they haven’t had a chance to assess the work for feasibility or scope. That conversation doesn’t happen until handoff. Can they actually build the specified designs in the next two weeks? If not, the work that went into designing those elements is waste.

Building Lean UX into the Rhythm of Scrum

As I said in the opening to this chapter, we tried using Staggered Sprints at TheLadders. And when we had problems, we continued to improve our process, eventually ending up with a deeply collaborative routine that played out across the rhythms of Scrum. Let’s take a look at how you can use Scrum’s meeting structure and Lean UX to build an efficient process.

Themes

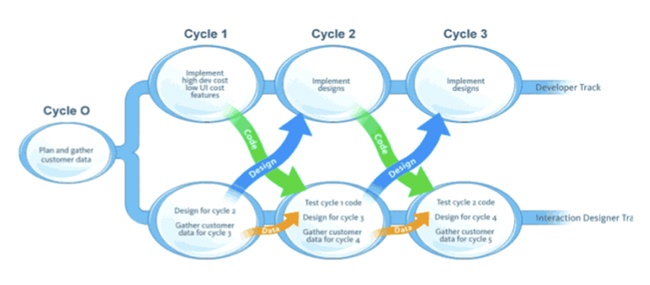

Scrum has a lot of meetings. Many people frown on meetings, but if you use them as mileposts during your sprint, you can create an integrated Lean UX and Agile process in which the entire team is working on the same thing at the same time.

Let’s take a two-week sprint model and assume that we can tie a series of these sprints together under one umbrella, which we’ll call a theme (Figure 7-2).

Kickoff Sessions for Sketching and Ideation

Each theme should be kicked off with a series of brainstorming and validation exercises like the ones described in Part II. These activities can be as short as an afternoon or as long as a week. You can do them with your immediate team or with a broader group. The scope of the theme will determine how much participation and time these kickoff activities require. The point of this kickoff is to get the entire team sketching and ideating together, creating a backlog of ideas to test and learn from.

Once you’ve started your sprints, these ideas will be tested, validated, and developed new knowledge will come in, and you’ll need to decide what to do with it. You make these decisions by running subsequent shorter brainstorming sessions that take place before each new sprint begins, which allows the team to use the latest insight to create the backlog for the next sprint. See Figure 7-3.

Iteration Planning Meeting

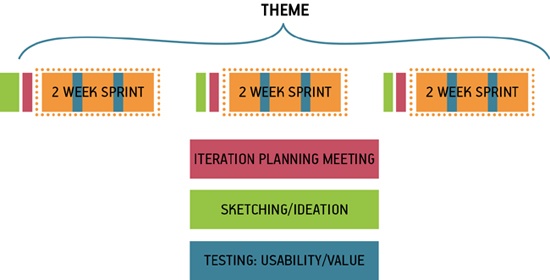

The output of the kickoff session should be brought to the iteration planning meeting (IPM). Your mess of sticky notes, sketches, wireframes, paper prototypes, and any other artifacts may seem useless to outside observers but will be meaningful to your team. You made these artifacts together and because of that, you have the shared understanding necessary to extract stories from them. Use them in your IPM (Figure 7-4) to write user stories together, then evaluate and prioritize the stories.

User Validation Schedule

Finally, to ensure a constant stream of customer voices to validate against, plan user sessions every single week (Figure 7-5). Your team will never be more than five business days away from customer validation but still your ideas will have ample time to react prior to the end of the sprint. Use the artifacts you created in the ideation sessions as the base material for your user tests. Remember that when the ideas are raw, you are testing for value (i.e., do people want to use my product?). Once you have established a desire for your product, subsequent tests with higher fidelity artifacts will reveal whether your solution is usable.

Participation

One of the big lessons I took away from the diagram I showed at the beginning of Part III was that designers need time to be creative. Two-week cycles of concurrent development and design offer few opportunities for creative time. Some Agile methods take a more flexible approach to time than Scrum does. (For example, Kanban does away with the notion of a two-week batch of work and places the emphasis on single-piece flow.) But you can still make time within a Scrum sprint in which creative activities can take place.

The reason my UX team at TheLadders wasn’t finding that time was that we weren’t fully participating in the Scrum process. This was not entirely our fault: the content of many Scrum meetings offered little value to UX designers. However, without our participation, our concerns and needs were not taken into account in project plans. As a result, we weren’t creating the time within sprints for creative work to take place—the rest of the team didn’t understand that this time was needed.

For Lean UX to work in Agile, the entire team must participate in all activities—standups, retrospectives, IPMs, brainstorming sessions—they all require everyone’s attendance to be successful. Besides negotiating the complexity of certain features, cross-functional participation allows designers and developers to create effective backlog prioritization.

For example, imagine at the start of a sprint that the first story a team prioritizes has a heavy design component to it. Imagine that the designer wasn’t there to voice his or her concern. That team will fail as soon as it meets for its standup the next day. The designer will announce that the story has not been designed. And he or she will say that it will take at least two or three days to complete the design before the story is ready for development. Imagine instead that the designer had participated in the prioritization of the backlog. His or her concern would have been raised at planning time. The team could have selected a story card that needed less design preparation to work on first, which would have bought the designer the time necessary to complete the work.

The other casualty of sparse participation is shared understanding. Teams make decisions in meetings. Those decisions are based on discussions. Even if 90 percent of a meeting is not relevant to your immediate need, the 10 percent that is relevant will save hours of time downstream explaining what happened at the meeting and why certain decisions were made.

Participation allows you to negotiate for the time you need to do your work. This is true for UX designers as much as it is for everyone else on the team.

Design Is a Team Sport: Knowsy Case Study

In this case study, designer and coach Lane Halley details how she brought to the table all the players—development, design, marketing, and stakeholders—to create a tablet game.

In my work as a product designer, I use Lean UX practices on a variety of projects. Recently I’ve worked on entertainment, ecommerce, and social media products for different platforms, including iPad, iPhone, and Web. The teams have been small, ranging from three to seven people. Most of my projects also share the following characteristics:

The project is run within an Agile framework (focus on the customer, continuous delivery, team sits together, lightweight documentation, team ownership of decisions, shared rituals like standups, retrospectives, etc.).

The team contains people with a mix of skills (front- and back-end development, user experience and information architecture, product management and marketing, graphic design, copywriting).

The people on the team generally performed in their area of expertise/strength but were supportive of other specialties and interested in learning new skills.

Most of the teams I work with create entirely new products or services. They are not working within an existing product framework or structure. In “green fields” projects like these, we are simultaneously trying to discover how this new product or service will be used, how it will behave and how we are going to build it. It’s an environment of continual change, and there isn’t a lot of time or patience for planning or up-front design.

The Innovation Games Company

The Innovation Games Company (TIGC) produces serious games—online and in-person—for market research. TIGC helps organizations get actionable insights into customer needs and preferences to improve performance through collaborative play. In 2010, I was invited to help TIGC create a new game for the consumer market.

I was part of the team that created Knowsy for iPad, a pass-and-play game that’s all about learning what you know about your friends, family, and coworkers, while simultaneously testing how well they know you. The person who knows the other players best wins the game. It is a fast, fun, and truly “social” game for up to six players.

It was our first iPad application, and we had an ambitious deadline: one month to create the game and have it accepted to the App Store. Our small team had a combination of subject-matter expertise and skills in front- and back-end development as well as visual and interaction design. We also asked other people to help us play-test the game at various stages of development.

A Shared Vision Empowers Independent Work

Until a new product is coded, it’s hard for people to work within the same product vision. You can recognize a lack of shared vision when the team argues about what features are important or what should be done first. There can also be a general sense that the team is not “moving fast enough,” or that the team is going back over the same issues again and again.

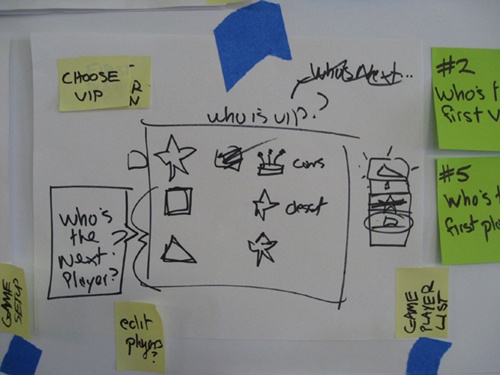

While working on Knowsy, I looked for ways that I could make my UX practice more collaborative, visual, lightweight, and iterative. I looked for opportunities to work in real time with other people on the team (such as developers and the product manager) and rough things out as quickly as possible at the lowest responsible level of fidelity.

As we found the right solutions and the team understood and bought into the design concept, I was able to increase fidelity of the design artifacts, confident that we shared a product vision (Figure 7-6).

Breaking the Design Bottleneck

Early in the project, I sat with the front-end developer to talk about the game design. We created a high-level game flow together on paper, passing the marker back and forth as we talked. This was my opportunity to listen and learn what he was thinking. As we sketched, I was able to point out inconsistencies by asking questions such as, “What do we do when this happens?” This approach had the benefit of changing the dialog from “I’m right and you’re wrong” to “How do we solve this problem?”

After we had this basic agreement, I was able to create a paper prototype (Figure 7-7) of the game based on the flow and play-test it with the team. The effect on the team was immediate. Suddenly everyone “got it” and was excited about what we were doing. People started to contribute ideas that fit together well, and we were able to identify which parts we could each work on that supported the whole.

Once we were all on the same page, it was easier for me to take some time away from the team and document what we’d agreed in a clickable prototype. See Figure 7-8.

The Outcome

Knowsy’s foray into Lean UX proved a success. We got the app to the Apple store by the deadline. I was called back later to help the team do another variant of the product. For that round, I used a similar process. Because I was working remotely and the dev team was not as available to collaborate, I had to make heavier deliverables. Nevertheless, the basic principle of iterating our way to higher fidelity continued.

Beyond the Scrum Team

Management check-ins are one of the biggest obstacles to maintaining team momentum. Designers are used to doing design reviews, but unfortunately, check-ins don’t end there. Product owners, stakeholders, CEOs, and clients all want to know how things are going. They all want to bless the project plan going forward. The challenge for outcome-focused teams is that their project plans are dependent on what they are learning. They are responsive, so their typical plan lays out only small batches of work at a time. At most, these teams plan an iteration or two ahead. This perceived “short-sightedness” tends not to satisfy most high-level managers. How then do you keep the check-ins at bay while maintaining the pace of your Lean UX and Scrum processes?

Two words: proactive communication.

I once managed a team that radically altered the workflow for an existing product that had thousands of paying customers. We were so excited by the changes we’d made that we went ahead with the launch without alerting anyone else in the organization. Within an hour of the new product going live, the VP of Customer Service was at my desk, fuming and demanding to know why she wasn’t told about this change. Turns out that when customers have problems with the product, they call in for help. Call center reps use scripts to troubleshoot the customers’ needs and offer solutions, and they didn’t have a script for this new product...because they didn’t know it was going to change.

This healthy slice of humble pie served as a valuable lesson. If you want your stakeholders—both those managing you and those dependent on you—to stay out of your way, make sure they are aware of your plans. Here are a few tips:

Proactively reach out to your product owners and executives.

Let them know:

How the project is going

What you tried so far and learned

What you’ll be trying next

Keep the conversations focused on outcomes (how you’re trending towards your goal), not feature sets.

Ensure that dependent departments (customer service, marketing, ops, etc.) are aware of upcoming changes that can affect their work.

Provide them with plenty of time to update their workflows if necessary.

Conclusion

This chapter took a closer look at how Lean UX fits into a Scrum process. In addition, I talked about how cross-functional collaboration allows a team to move forward at a brisk pace and how to handle those pesky stakeholders and managers who always want to know what’s going on. I discussed why having everyone participate in all activities is critical and why the staggered sprint model is only a way-point on the path to true agility.

In the next and final chapter, we’ll take a look at the organizational shifts that need to be made to support Lean UX. This chapter can serve as a primer for managers on what they’ll need to do to set teams up for success.