Chapter 8. Making Organizational Shifts

Earlier in this book, I discussed the principles behind Lean UX. I hope you understand from that section that Lean UX is a mindset. I’ve also discussed some of the key methods of Lean UX, because Lean UX is also a process. As I’ve worked with clients and taught these methods to teams, it’s become clear that Lean UX is also a management method. For this reason, you’ll need to make some changes in your organization in order to get the most benefit from working this way.

When I train teams, they sometimes ask me, “How can I put these methods into practice here?” On this point, I’m a little hesitant. Although I’m confident that most organizations can solve these problems, I’m also aware that every organization is different. Finding the right solution is going to require a lot of close work and collaboration with your colleagues.

To prepare you for that work, I’m going to use this chapter to share with you some of the shifts that organizations need to make in order to embrace Lean UX. I’m not going to tell you how to make those shifts. That’s your job. But I hope this discussion will help you survey the landscape to find the areas that you’re going to address.

In this chapter, we’ll discuss the following changes your organization may need to make in these areas:

Shifting from output to outcomes

Moving from limited roles to collaborative capabilities

Embracing new skills

Creating small teams

Creating open, collaborative workspaces

Not relying on heroes

Eliminating “Big Design Up Front”

Placing speed first, aesthetics second

Valuing problem solving

Embracing UX debt

Shifting agency culture

Working with third-party vendors

Navigating documentation standards

Being realistic about your environment

Managing up and out

SHIFT: Outcomes

In Chapter 3, I discussed the role of outcomes in Lean UX. Lean UX teams measure their success not in terms of features completed but in terms of progress toward specific outcomes. Determining outcomes is a leadership activity, one that many organizations are not good at or don’t do at all. Too often, leadership directs the product team through a product roadmap—a set of outputs and features that they require the product team to produce

Teams attempting to use Lean UX must be empowered to design the solutions to the business problems with which they are tasked. In other words, they must be empowered to decide for themselves which features will create the outcomes their organizations require. To do this, teams must shift their conversation with leadership from one based on features to one centered on outcomes, and this conversational shift is a radical one. Product managers and product owners must determine which business metrics require the most attention. In turn, they must have conversations around outcomes with their managers. In this way, the shift will inevitably go to the highest levels of the organization.

Leadership must set this direction, and teams must demand this shift from leadership. Managers have to be retrained to give their teams the latitude to experiment. Product requirements conversations must then be grounded in business outcomes: what are we trying to achieve by building this product? This rule holds true for design decisions as well. Success criteria must be redefined and roadmaps must be done away with. In their place, teams build backlogs of hypotheses they’d like to test and prioritize them based on risk, feasibility, and potential success.

SHIFT: Roles

In most companies, the work you do is determined by your job title. That job title comes with a job description. Too often, people in organizations discourage others from working outside the confines of their job descriptions (e.g., “You’re not a developer, what can you possibly know about JavaScript?”). This approach is deeply anticollaborative and means that workers’ full range of skills, talents, and competencies are unused.

Discouraging cross-functional input encourages organizational silos. The more discrete a person’s job is, the easier it becomes to retreat to the safe confines of that discipline. As a result, conversation across disciplines wanes and mistrust, finger-pointing, and “cover your ass” (CYA) behavior grows. Silos are the death of collaborative teams.

For Lean UX to succeed, your organization needs to adopt a mantra of “competencies over roles.” Every team member possesses a core competency—design, software development, research, etc.—and must deliver on that skill set. However, he or she may also possess secondary competencies that make the team work more efficiently.

Allow your colleagues to contribute in any disciplines in which they have expertise and interest. You’ll find that working this way creates a more engaged team that can complete tasks more efficiently. You’ll also find that it builds camaraderie across job titles, as people with different disciplines show interest in what their colleagues are doing. Teams that enjoy working together produce better work.

SHIFT: New Skills for UX Designers

Many companies hire designers to create wireframes, specs, and site maps. This hiring is done to fill the “design” phase of the waterfall process. Plugging interaction designers into these existing workflows limits their effectiveness by limiting the scope of their work, which has a side effect of reinforcing a siloed team model.

The success of a collaborative team demands more. Although teams still need core UX skills, designers must add facilitation as one of their core competencies. This change requires two significant shifts to the way we’ve worked to date:

- Designers must open up the design process.

The team—not the individual—must own the product design. Instead of hiding behind a monitor for days at a time, designers must bring teams into the design process, seek their input, and build that insight into the design. Doing so will begin to break down silos and allow a more cross-functional conversation to take place.

- Designers must take a leadership role on their team.

Your colleagues are used to critiquing your design work. What they’re not used to doing is co-creating that design with you. Your leadership and facilitation in group brainstorming activities such as Design Studio can create safe forums for the entire team to conceptualize your product.

SHIFT: Cross-Functional Teams

For many teams, collaboration is a single-discipline activity. Developers solve problems with other developers, while designers go sit on bean bags, fire up the lava lamps, and “ideate” with their black-turtlenecked brethren (I’m kidding...I love designers!).

The ideas born of single-discipline collaborations are single-faceted. They don’t reflect the broader perspective of the team, which can illuminate a wider range of needs, such as the needs of the customer, the business, or the technology. Worse, working this way requires discipline-based teams to explain their work to one another. Too often, the result is a heavy reliance on detailed documentation.

Lean UX requires cross-functional collaboration. By creating interaction between product managers, developers, QA engineers, designers, and marketers, you put everyone on the same page. Equally important: you put everyone on the same level. No single discipline dictates to the other. All are working toward a common goal. Allow your designers to attend “developer meetings” and vice versa. In fact, just have team meetings.

We’ve known how important cross-functional collaboration is for a long time. Robert Dailey’s study from the late 1970s, “The Role of Team and Task Characteristics in R & D Team Collaborative Problem Solving and Productivity,”[3] found a link between a team’s problem solving productivity and what he called “four predictors”: task certainty, task interdependence, team size, and team cohesiveness. Keep your team cohesive by breaking down the discipline-based boundaries.

SHIFT: Small Teams

Larger groups of people are less efficient than smaller ones. This makes intuitive sense. But less obvious is this: a smaller team must work on smaller problems. This small size makes it easier to maintain the discipline needed to produce minimum viable products. Break your big teams into what Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos famously called “two-pizza teams” (http://www.fastcompany.com/50106/inside-mind-jeff-bezos). If the team needs more than two pizzas to make a meal, it’s too big.

SHIFT: Workspace

Break down the physical barriers that prevent collaboration. Co-locate your teams and create workspaces for them that keep everyone visible and accessible. Make space for your team to put their work up on walls and other work surfaces. Nothing is more effective then walking over to a colleague, showing some work, discussing, sketching, exchanging ideas, understanding facial expressions and body language, and reaching a resolution on a thorny topic.

When you co-locate people, create cross-functional groupings. That means removing team members from the comforts of their discipline’s “hideout.” It’s amazing how even one cubicle wall can hinder conversation between colleagues.

Open workspaces allow team members to see each other and to easily reach out when questions arise. Some teams have gone as far as putting their desks on wheels so they can relocate closer to the team members with whom they’re collaborating on that particular day. Augment these open spaces with breakout rooms where the teams can brainstorm. Wall-sized whiteboards or painting the walls with whiteboard paint provides many square feet of discussion space. In short, remove the physical obstacles between your team members. Your space planners may not like it at first, but your stakeholders will thank you.

If co-location is not an option, give teams the tools they need to communicate. These include things like video conferencing software (e.g., Skype) and smart boards, but also plane tickets to meet each other in the flesh every now and again. It’s amazing what one or two in-person meetings a year will do to team morale.

SHIFT: No More Heroes

On the teams that I’ve worked with to date, it hasn’t been developers who have pushed back on Lean UX. It is designers who have resisted the most. The biggest reason? Many designers want to be heroes.

In an environment in which designers create beautiful deliverables, they can attain a heroic aura. Requirements go in one end of the design machine and gorgeous artwork makes its way out. People “ooh” and “aah” when the design is unveiled. Designers have thrived on these reactions (both informal and formalized as awards) for many years.

I’m not suggesting that all of these designs are superficial. Schooling, formal training, experience, and a healthy dose of inspiration go into every Photoshop document designers create—and often the results are smart, well-considered, and valuable. However, those glossy deliverables can drive bad corporate decisions. They can bias judgment specifically because their beauty is so persuasive. Awards are based on the aesthetics of the designs (rather than the outcome of the work), hiring decisions are made on the sharpness of wireframes, and compensation depends on the brand names attached to each of the portfolio pieces.

The creators of these documents are heralded as thought leaders and elevated to the top of the experience design field. But can a single design hero be responsible for the success of the user experience, the business, and the team? Should one person be heralded as the sole reason for an initiative’s success?

In short, no!

For Lean UX to succeed in your organization, all types of contributors—designers and nondesigners—must collaborate broadly. This change can be hard for some, especially for visual designers with a background in interactive agencies. In those contexts, the Creative Director is untouchable. In Lean UX, the only thing that’s untouchable is customer insight.

Lean UX literally has no time for heroes. The entire concept of design as hypothesis immediately dethrones notions of heroism; as a designer you must expect that many of the your ideas will fail in testing. Heroes don’t admit failure. But Lean UX designers embrace it as part of the process.

No More BDUF, Baby

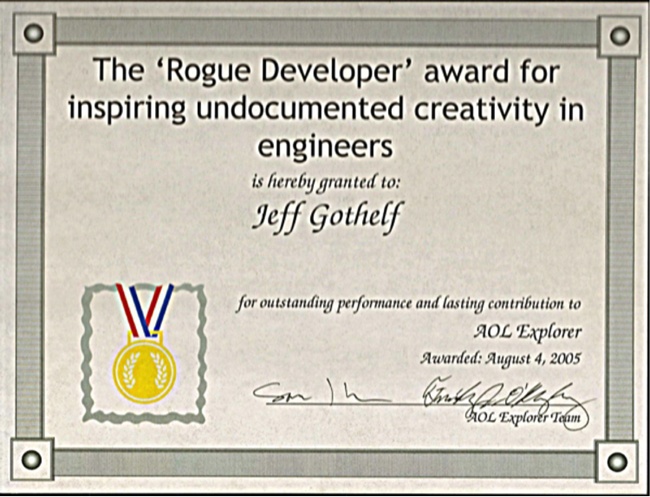

In the Agile community, you sometimes hear people talk about Big Design Up Front, or BDUF. I’ve been advocating moving away from BDUF for years. But it wasn’t always that way.

In the early 2000s, I was a user interface designer at AOL, working on a new browser. The team was working on coming up with ways to innovate upon existing browser feature sets. But they always had to wait to implement anything until I’d created the appropriate mockups, specifications, and flow diagrams that described these new ideas.

One developer got tired of waiting for me and started implementing some of these ideas before the documents were complete. Boy, was I upset! How could he have gone ahead without me? How could he possibly know what to build? What if it was wrong or didn’t work? He’d have to rewrite all the code!

Turned out that the work he did allowed us to see some of these ideas much sooner than before. It gave us a glimpse into the actual product experience and allowed us to quickly iterate our designs to be more usable and feasible. From that moment on, we relaxed our BDUF requirements, especially as we pushed into features that required animations and new UI patterns.

The irony of the team’s document dependency and the “inspiration” it triggered in that developer was not lost on us. In fact, at the end of the project, I was given a mock award for inspiring “undocumented creativity” in a teammate.

SHIFT: Speed First, Aesthetics Second

Jason Fried, CEO of 37Signals, once said “Speed first, aesthetics second” (https://twitter.com/jasonfried/status/23923974217). He wasn’t talking about compromising quality. He was talking about editing his ideas and process down to the core. In Lean UX, working quickly means generating many artifacts. Don’t waste time debating which type of artifact to create, and don’t waste time polishing them to perfection. Instead, use the one that will take the least amount of time to create and communicate to your team. Remember, these artifacts are a transient part of the project—like a conversation. Get it done. Get it out there. Discuss. Move on.

Aesthetics—in the visual design sense—are an essential part of a finished product and experience. The fit and finish of these elements make a critical contribution to brand, emotional experience, and professionalism. At the visual design refinement stage of the process, putting in the effort to obsess over this layer of presentation makes a lot of sense. However, putting in this level of polish and effort into the early stage artifacts—wireframes, sitemaps, and workflow diagrams—is a waste of time.

By sacrificing the perfection of intermediate design artifacts, your team will get to market faster and learn more quickly which elements of the whole experience (design, workflow, copy, content, performance, value propositions, etc.) are working for the users and which aren’t. And you’ll be more willing to change and rework your ideas if you’ve put less effort into presenting them.

SHIFT: Value Problem Solving

Lean UX makes us ask hard questions about how we value design.

If you’re a designer reading this, you’ve probably asked yourself a question that often comes up when speed trumps aesthetic perfection:

If my job is now to put out concepts instead of finished ideas, every idea I produce feels half-assed. In fact, I feel like I’m “going for the bronze.” Nothing I produce is ever finished. Nothing is indicative of the kind of products I am capable of designing. I am putting out bronze-medal work—on purpose! How can I feel pride and ownership for designs that are simply not done?

For some designers, Lean UX threatens what they see as their collective body of work, their portfolio, and perhaps even their future employability. These emotions are based on what many hiring managers have valued to date—sexy deliverables. Rough sketches, “version one” of a project, and other low-fidelity artifacts are not the makings of a “killer portfolio,” but all of that is now changing.

Although your organization must continue to value aesthetics, polish, and attention to detail, the ability to think fast and build shared understanding must get a promotion. Designers can demonstrate their problem solving skills by illustrating the path they took to get from idea to validated learning to experience. In doing so, they’ll demonstrate their deep worth as designers. Organizations that seek out and reward problem solvers will attract—and be attracted to—those designers.

Shift: UX Debt

It’s often the case that teams working in agile processes do not actually go back to improve the user interface of the software. But, as the saying goes, “it’s not iterative if you only do it once.” Teams need to make a commitment to continuous improvement, and that means not simply refactoring code and addressing technical debt but also reworking and improving user interfaces. Teams must embrace the concept of UX debt and make a commitment to continuous improvement of the user experience.

James O’Brien, an interaction designer working in London, describes what happened when his team started tracking UX debt in the same way the team tracked technical debt: “The effect was dramatic. Once we presented [rework] as debt, all opposition fell away. Not only was there no question of the debt not being paid down, but it was consistently prioritized.”[4]

To use the concept of UX debt, write stories to capture a gap analysis between where the experience is today and where you’d like it to be. Add these stories to your backlog. Advocate for them.

SHIFT: Agencies Are in the Deliverables Business

Applying Lean UX in an interactive agency is no small challenge. Most agencies are set up in ways that make it difficult to implement Lean UX, which is based on cross-functional collaboration and outcome-focused management. The basic agency business model is simple, after all: clients pay for deliverables, not outcomes. But agency culture is a huge obstacle as well. The culture of hero design is strong in places that elevate individuals to positions such as Executive Creative Director. Cross-disciplinary collaboration can also be difficult in big agencies, where processes and “project phases” encourage deliverables and departmental silos.

Perhaps the most challenging obstacle is the client’s expectation to “throw it over the wall” to the agency, then see the results when they’re ready. Collaboration between client and agency in this case can be limited to uninformed and unproductive critique that is based on personal bias, politics, and CYA.

To make Lean UX work in an agency, everyone involved in an engagement must focus on maximizing two factors: increasing collaboration between client and agency, and working to change the focus from outputs to outcomes.

Some agencies attempt to focus on outcomes by experimenting with a move away from fixed-scope and deliverable-based contracts. Instead, their engagements are based on simple time-and materials agreements, or, more radically, on outcome-based contracts. In either case, the team is freed to spend their time iterating towards a specified goal, not just a deliverable. Clients give up the illusion of control that a deliverables-based contract offers but gain a freedom to pursue meaningful and high-quality solutions that are defined in terms of outcomes, not feature lists.

To increase collaboration, agencies can try to break down the walls that separate them from their clients. Clients can be pulled in to the process earlier and more frequently. Check-ins can be constructed around less formal milestones. And collaborative work sessions can be arranged so that both agency and client benefit from the additional insight, feedback, and collaboration with one another.

These are not easy transformations—neither for the agency nor the client who hires it—but it is the model under which the best products get built.

A Quick Note about Development Partners

In agency relationships, software development teams (either at the agency, at the client, or a third-party team) are often treated as outsiders and often brought in at the end of a design phase. It’s imperative that you change this tradition: development partners must participate through the life of the project—and not as passive observers. Instead, you should seek to have software development start as early as possible. Again, you are looking to create a deep and meaningful collaboration with the entire project team—and to do that, you must actually be working side by side with the developers.

SHIFT: Working with Third-Party Vendors

Third-party software development vendors pose a big challenge to Lean UX methods. If a portion of your work is outsourced to a third-party vendor—regardless of the location of the vendor—the Lean UX process is more likely to break down. The contractual relationship with these vendors can make the flexibility that Lean UX requires difficult to achieve.

When working with third-party vendors, try to create projects based on time and materials. Doing so will make it possible for you to create a flexible relationship with your development partner, which you need in order to respond to the changes that are part of the Lean UX process. Remember, you are building software to learn, and that learning will cause your plans to change. Plan for that change, and structure your vendor relationships around it.

SHIFT: Documentation Standards

Many organizations have strict documentation standards that help them meet both internal as well as external and regulatory compliance. Regardless of the value these documents bring to the team, the organization demands that these be created in a certain way and within certain guidelines. Attempting to circumvent this step will inevitably lead to rework, delays, and dissatisfaction with your work performance.

This situation is exactly when, as designer and coach Lane Halley put it, you “lead with conversation, and trail with documentation.” The basic philosophies and concepts of Lean UX can be executed within these environments—conversation, collaborative problem solving, sketching, experimentation, and so on—during the early parts of the project lifecycle. As hypotheses are proven and design directions solidify, transition back from Lean UX to the documentation standard your company requires. Use this documentation for the exact reason your company demands: to capture decision history and inform future teams working on this product. Don’t let it prevent you from making the right product decisions.

SHIFT: Be Realistic about Your Environment

Change is scary. The Lean UX approach brings with it a lot of change. Change can be especially disconcerting for managers who have been in their position for a while and are comfortable in their current role. Some managers may be threatened by proposals to work in a new way, which could result negative consequences for you. In these situations, try asking for forgiveness rather than permission. Try out some ideas and prove their value via quantifiable successes. Whether you saved time and money on the project or put out a more successful update than ever before, these achievements can help make your case. If your manager still doesn’t see the value in working this way and you believe your organization is progressing down a path of continued “blind design,” perhaps it’s time to consider alternative employment.

SHIFT: Managing Up and Out

Lean UX gives teams a lot of freedom to pursue effective solutions. It does this by stepping away from a product roadmap approach, instead empowering teams to discover the features they think will best serve the business. But abandoning the product roadmap has a cost—it removes a key tool that the business uses to coordinate the activity of teams. So with the freedom to pursue your agenda comes a responsibility to communicate that agenda.

You must constantly reach out to members of your organization who are not currently involved in your work to make sure they’re aware of what’s coming down the pike. This communication will also make you aware of what others are planning and help you coordinate. Customer service managers, marketers, parallel business units, and sales teams all benefit from knowing what the product organization is up to. By reaching out to them proactively, you allow them to do their jobs better. In return, they will be far less resistant to the changes your product designs are making.

Two valuable lessons to ensure smoother validation cycles:

There are always other departments that are affected by your work. Ignore them at your peril.

Ensure that customers are aware of any significant upcoming changes and allow them to opt out (at least temporarily).

A Last Word

Just as we were putting the final touches on this chapter, we got an email from a colleague. Sometimes it can feel impossible to change the entrenched habits of an organization. So I was delighted to receive this email, which I’ve excerpted for you here, in which Emily Holmes, Director of K12 UX at Hobsons, describes the changes she’s made in her organization:

I think a lot of enterprise companies struggle to figure out the best way to implement these techniques. We initially got a great deal of resistance that we couldn’t do Lean UX because we’re “not a startup,” but of course that’s really not true.

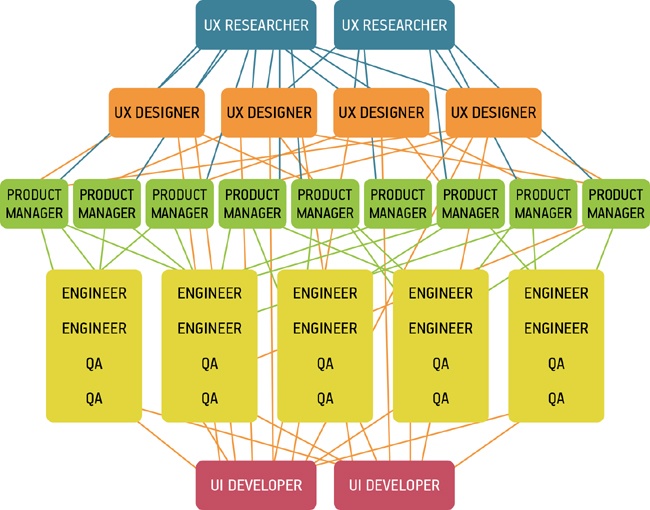

We brought in a coach to help reinforce with the team our goal of moving our development process toward a Lean UX methodology (it can help to have an outside voice to reinforce what’s being said internally), and since then we’ve made good progress. In less than a year, our team structure has moved from this:

To this:

I have introduced the following system for helping our teams internalize what needs to happen as we move through the discovery phase of a project, so that we don’t skip any steps and everyone can begin to understand why this thought process needs to happen.

It requires ongoing coaching on my part, and we haven’t completely mastered it yet, but it is really helping to get the full team in sync and speaking the same language. That’s no small feat, as our team includes people who are accustomed to business analysis, technical specs, and waterfall development. It’s a little bit fun, so people don’t feel too resentful about having to change old habits. And it definitely helps us fight the “monsters” that have traditionally been problematic for our organization.

I believe a lot of the things that are working for us could be applied to other enterprise organizations quite successfully.

I believe that, too, and I hope that the shifts and principles I’ve outlined in this chapter will help guide you.

Conclusion

Lean UX is the evolution of product design. It blends the best interaction design techniques with the scientific method to create products that are easy to use, beautiful, and measurably successful. By blending the ideas behind Lean Startup, Agile software development, and design thinking, this approach takes the bloat and uncertainty out of product design and pushes it toward an objectively grounded result. I hope the tactics, strategies, and case studies in this book were useful to you. I am eager to continue the conversation beyond the book and would love to hear from you as you set out to build your Lean UX teams. As you succeed and as you fail, let me know. I want to treat this book as a snapshot in time and use all of your insights to continue to push for better design, team dynamics, and success. Email me at [email protected] or email Josh at [email protected] with your stories. We look forward to hearing from you.