1

Mindfulness

From the quiet reflection will come even more effective action.

PETER DRUCKER

Wisdom of Perhaps

Donald Altman, psychotherapist and author of books on mindfulness, likes to tell a story that he calls “The Wisdom of Perhaps.” The tale has been told and retold in many different forms, but here’s a quick synopsis.

A man comes home early from work and his neighbor asks him why. The man replies that he has just lost his job. The neighbor says, “That’s the worst thing that could happen to you.” The man replies, “Perhaps.”

A day or so later the man encounters an old friend in the banking industry. When the friend learns that the man is out of work, he offers him a job as a senior executive right on the spot. The man accepts and the next day arrives at work so early that the moving crew is still there. The man lends a hand and, as luck would have it, wrenches his back and goes home. When the neighbor hears what happens, he says, “You’re the unluckiest guy in the world.” To which the man replies, “Perhaps.”

The next day the bank is robbed and employees are held hostage, and of course the neighbor has a response. “Boy, are you lucky you hurt your back.” “Perhaps,” the man replies.

Events occur, often outside our control. What we can control is our response to those events. As Altman explains, “One little event doesn’t define us, one adversity doesn’t define us.” Often when we reflect on our lives, according to Altman, “Adversity actually has a silver lining. So we can take the attitude of perhaps with us on a daily basis.”

Mindfulness gives individuals the perspective to take a step back and reflect on the situation. Things can be bad, of course, but it falls to the leader to seek to make things better.

Mindfulness. People with moxie know that good things happen to those who seek them. Such folks are aware of their situation and, most importantly, are aware of their ability to effect positive change.

Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela liked tea.

Certainly he enjoyed the briskness of an afternoon cup. Or perhaps he liked the fact that it was a habit of the English, one he had learned while studying law at Oxford as a young man. Whatever his reasons, Mandela used the ritual of afternoon tea as an extension of his warm and open personality, particularly when greeting guests. Tea, which he always insisted that he pour, also became a symbol of control.

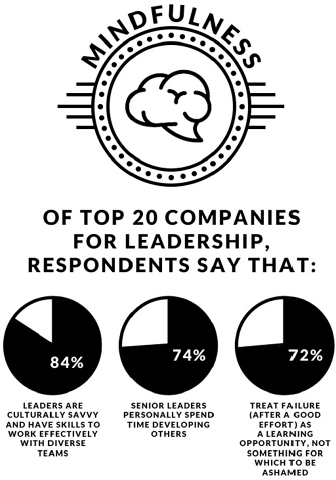

SOURECE: 2013 BEST COMPANIES FOR LEADERSHIP HAY GROUP1

When, after nearly decades of captivity, it became apparent that he would eventually be released, the South African government decided that it must learn to deal with Mandela as a political force that might one day rule the country. For that reason, the prison authorities gave him his own house on the grounds of a mainland prison, and when government officials came calling, Mandela played host. Even though he was a prisoner, he was the master of his house. He was its lord as well as the designated tea pourer. In this way, Mandela slowly, and not coyly, asserted himself as one who must be reckoned with.

World leaders come and go, but few have captured the imagination like Nelson Mandela. Born into royalty in his homeland, he assumed chiefly duties. Seeking wider influence, he soon ran smack into the vicious and oppressive apartheid system designed to keep black Africans, the overwhelming majority, in a state of subjugation.

As head of the African National Congress, Mandela was tried on terrorism charges and sentenced to five years in prison in 1961. He was sent to Robben Island, a remote spit of rock in the Indian Ocean, four miles off the coast of Cape Town. Later, when his papers were found in a distant farmhouse, Mandela, still in prison, was tried on treason charges and sentenced to death. His death sentence was later commuted but the hardships endured. He pounded rocks in the blazing sun day after day, years upon end. It was mindfulness, as well as the cohesion of his comrades on Robben Island, that enabled him and his fellow prisoners to persevere.

While such treatment may have broken a lesser man, it only fueled Mandela’s conviction. On the plus side, he was surrounded by his brothers in arms, fellow members of the ANC. In time, he was hailed as the hero of the liberation movement in South Africa, which gained momentum during the years of his incarceration.

During this time, Mandela looked forward, and in doing so, learned Afrikaans, the language of his jailers, as well as Afrikaner culture. He came to understand that, unlike the English, who might re-emigrate to Britain or another commonwealth nation like Canada or Australia should black people come to government, the Afrikaners, descendants of Dutch farmers who had emigrated to Southern Africa in the seventeenth century, were home. They referred to themselves as Africa’s White Tribe, and they were not going anywhere.

After Mandela was released to worldwide acclaim and adulation in 1993, he traveled the world. When it was decided that there would be free and fair elections, he ran for president and won. This thrilled the hearts of his fellow Africans, but absolutely terrified the whites. Mandela, being a wise man with a capacity for human understanding that dwarfed most others, understood that he needed to pull the nation together. His method was rugby. South Africa, long banned from international sports competition, was designated the host nation for the Rugby World Cup of 1995. This was a huge deal for the Afrikaner population, less so for fellow Africans. But Mandela understood that this was his opportunity to make a statement to Afrikaners that he needed them as partners in the government as well as partners in the nation.

As told in the book Playing the Enemy (and later depicted in the movie Invictus) Mandela ensured that Afrikaner tradition in rugby would be upheld. The Springbok emblem, a symbol of oppression to Africans, was allowed to remain as the symbol of the team. The team itself was all white save for one player of mixed-race background. Mandela took personal interest in the team, in particular its captain, Francois Pienaar, and in doing so he helped infuse the team with a sense of playing for their country—white and black. The Springboks were underdogs, but with a sense of destiny pulled off the upset of the era, ensuring that, if only for a moment, there was one South Africa.

Only someone with Mandela’s sense of purpose could have shepherded a nation whose government was so virulently racist through a peaceful transition that facilitated reconciliation and allowed the country to survive.

Myth surrounds Mandela, and on the one hand it’s glorious and fitting. Few men have ever endured such oppression and emerged so unscathed, at least in a moral sense. He was kind, compassionate, and generous, but he was also steeled for his duty. He suffered losses in his family, and eventually in his marriages, but he remained true to his cause.2

*****

Mandela exemplifies what it means to be mindful: aware of your situation but at the same time focused on what you can do to improve it. Many people saw the need for change in South Africa, but only a few activists were willing to take the risks involved to fight this uphill battle. Luckily, for most of us the stakes are not so high; still, we can all learn from Mandela’s example and it holds relevance for us today.

One of the things I like to do when I begin a coaching engagement is ask my new client this question: What gets you up in the morning? If I see a smile come to the person’s eyes, I know that I have tapped into something powerful—what he enjoys doing. The answers are as varied as the executives. Some get excited by tackling new challenges; others enjoy problem solving; others like the thrill of competition; and many like working with their teams to achieve intended results. The answers to this question open the door to greater understanding. When an executive says he likes to see what his team is accomplishing, I know that I am working with an individual who is placing an emphasis on the right thing, working with the team. On the other hand, if the individual says she likes working on projects and contributing in that way I realize that she is more suited to being an individual contributor.

The most troubling answer, or, more precisely, nonanswer, comes from the individual who shows little interest in the work. His answer may be a symptom of burnout or it may be an indication that he does not find the work challenging. In either case, this person is going through the motions. It happens to the best of us. Situations at work may change, so what we once liked to do is no longer possible or we lack the motivation to continue much longer.

My advice is to find something else about the job that you love. Or perhaps look to things you like to do outside of work. Tap into your passion. When the low point comes, and most worthwhile endeavors have a moment when the obstacles look large, you will need that passion to push you through it.

Self-Awareness

Knowing what gets you enthused comes down to self-awareness. The capacity to know oneself is essential to being a leader. Self-awareness is the ability to understand yourself as well as to know how others perceive you. Too often, we overlook self-awareness as an important attribute of strong leadership.

According to a 2012 survey of 17,000 employees, conducted by the Hay Group, only 19 percent of executives possessed a degree of self-awareness. As Ruth Malloy, a vice president with Hay Group, put it in an interview: “If you think about most people in our day-to-day lives, we tend to run on autopilot. We often are not mindful about our impact on others or how and when we spend our time. We can easily get caught up in the task or the day-to-day distractions.”3 As a result we lose touch with ourselves. How we build our self-awareness says something about how we will succeed as leaders. The first step is acknowledging that we have work to do. Often that comes from feedback we receive from a trusted source, be it a boss or a colleague. Applying that feedback so we make positive changes is essential. Malloy told me, “Developing self-awareness requires reflection.” This echoes advice I have heard from other executives that you, as a leader, must build reflection time into your schedule. It could be alone time; it could be time shared with colleagues. The point is to find an opportunity to get perspective on your situation and think about what you need to do next. Or, as Malloy said, to think about “how you could react differently in the future.”4

It is not unusual, for example, for a leader to have a number of employees who liked the old way the company did things, and who find her passion frightening. If you are not aware of what others think of you or the situation, then it can be difficult to connect with them. Leadership requires persuasion, and that can only occur if the parties understand each other. We develop self-awareness when we take time to learn from others as well as listen to what others tell us. Self-aware leaders know what is happening around them; they live in the present but are aware of the future. They know that what they do has consequences, and for that reason they are attentive to how they interact with others.

The fact that so many executives are lacking in self-awareness resonates with my work in coaching.5 I like to say that executives are so busy focusing on others that they often overlook themselves, specifically the effect their actions may have on others. This is not always bad. An executive who is setting the right example in terms of his communications may not be aware of how well he is connecting with others. By contrast, a manager who is deficient in his ability to delegate work may not realize how much of a micromanager he has become. Self-awareness is fueled by mindfulness, the ability to think and act in the present. Mindfulness is a state of being, and it requires attentiveness to the here and now as well as to what is happening with others.

Self-Knowledge

Savvy leaders develop self-knowledge through mindful practice. It can begin with patience. For the many leaders whose internal motor powers them to act, the concept of patience can seem foreign. It can be perceived as passivity. In actuality, patience is an active process. While we cannot control the situation, we can control how we react to it.

Mindfulness, as described by psychotherapist and best-selling author Donald Altman, enables us “to find a state of equanimity.” As Altman says, “The brain is Velcro for negativity, and so we can be tilted emotionally in a way that does not allow us to be effective.”6 Mindfulness enables us to check our emotions so we can discern things with a clearer perspective. As such, mindfulness enables us to listen, engage, and connect with others in a more open and honest way.

“The interesting thing is that mindfulness changes our experience of whatever is happening,” says Altman. We may harbor negative thoughts or feelings, but when we apply mindfulness we change the experience. We put it into perspective and, therefore, as Altman says, we can observe it. “The emotion becomes the object of our attention,” not the subject of it. This distancing enables us to separate the negative thoughts from individuals and in doing so remain more focused and more attentive. “What we’re doing is we’re calming ourselves and we’re observing in a neutral, nonjudging way,” Altman says. “It’s a major shift in perspective.”

“Mindfulness lets you see things in a very fresh way,” says Altman. “Think about when you were a child and you had that childlike ability, that first time that maybe you saw that flower or the first time that you witnessed something in nature and were just so engrossed in it, right? And so I think what happens with mindfulness, we start to see things in a very fresh and childlike way. I like to say there’s déjà vu, having been there before, mindfulness is more like vuja de, never having been there before.”

For example, you go into a supermarket and every cashier point is five deep with customers, each pushing a large basket. You move to the self-checkout line and the lines are just as long. You can’t control the crowd, but you can control your response. To be honest, when I see lines like that I am tempted to exit and shop someplace else, but in reality that would probably end up costing me more time. So I have learned, with much effort, to fall into the line and wait. My trick is to smile, even though inside I am roiling with irritation. I will chat with fellow customers, and when I get to the cashier, finally, I will not say something nasty—though I may be tempted—I will make light of the situation and talk about how much I enjoyed standing in line.

Silly, yes, but I am the one maintaining composure. I am exerting my patience so that I do not do something stupid and yell at the cashier, who is not at fault for the long lines. It does no good to yell at the manager either. Suggesting that he implement a better time- and work-flow management system makes you sound like a jerk.

Patience, as our mothers taught us, is a virtue. When it comes to mindfulness, patience is the door opener that makes time for us to notice things around us. Applying patience in the workplace means making time for employees and keeping an open-door policy so employees feel free to come in and chat. It sends a signal that you value their contributions.

Mindfulness also means you make time to reflect on what you observe and what you hear. It does no good to listen and not act. That is, when you hear about things going wrong, as a manager you need to find a solution, or better yet delegate someone to get the resources to solve the problem for the team.

Mindfulness requires practice. Consider it, says Altman, “as an awareness of the body … and the mind.” The process is “experiential.” You build up the practice of it through disciplined observation and being present but also through physical action. Breath control is key. By focusing on breath, something borrowed from yoga, the individual can slow down the external world and focus on the internal.

“Mindfulness is a practice; it’s a skill, like anything else,” says Altman. “And eventually you start working on it and you start building up the ability to do it more and more frequently. And I think that as you do—it’s a kind of meta-awareness. So it’s an awareness of the body. It’s an awareness of the mind. It’s a different kind of awareness and you start to know it firsthand. So it’s very much experiential. It’s very different from talking about it and experiencing it, two very different things. You can talk about what it’s like to hit a baseball and what you need to hit a baseball out of the park. It’s a very different thing to stand in the batter’s box and have that ball come at you at ninety, ninety-five miles an hour and learn how to swing, and that’s the skill.”

Altman says that mindfulness is an intentional process that enriches the way we interact with others. “Mindfulness gives you a deeper experience of being alive. [It] gives us a deeper feeling of being alive. Mindfulness also helps us create more loving, healthy, and sustainable relationships.”

Focus Awareness Outward

Jim Kouzes, a prominent leadership researcher and executive educator, believes that truly self-aware individuals are mindful of what’s happening around them. In workshops that Kouzes conducts he often engages participants in self-awareness-building exercises in which they work in groups of two or three. As they interact with one another, Kouzes “asks people to pay attention to self, initially—asking, How are you feeling now? How is your body reacting? Is your stomach tense? Are you nervous?” Then Kouzes shifts the point of view when he asks the participants, “Are you focused on the other person (in your group)? Are you distracted, looking away?” The exercise is simple, but when carried into subsequent rounds, the participants gradually begin to notice more about the other person (or persons) in their group.

Kouzes says that initially participants feel uneasy because this kind of focused observation is different from their normal routine, but “after a few minutes of doing it, [the observation] becomes relatively easy for people.” The point is that we can train ourselves to be mindful of our own thoughts and feelings, and we can do the same with others. And, being mindful of the situation around us is critical to developing an ability to connect with others.

It is not easy. As Rich Sheridan, cofounder and CEO of Menlo Innovations, an Ann Arbor–based software firm, notes, “As a leader you’re pulled simultaneously in two directions constantly. And I think that is the challenge of leadership. There’s that one aspect of leadership that requires the ability to envision a better future than where you’re at today and that requires you to lift your head up and look down the road as far as you can.” “But that only gets you kind of half the way there because the other part is, what’s happening today?” says Sheridan. “What’s happening right now? If I lift my head up and only look five miles down the road to try and figure out what’s ahead, I’m very likely to stumble. I’m very likely to trip over something that’s right in front of me, stub my toe, fall down, skin my knee, or slow down because I’m not paying attention to the stuff that’s happening today, right now.”

Mark Goulston, MD, a psychiatrist and executive coach, takes the observation to another level. “Noticing is different than watching. Looking or seeing [something] is being completely present and engaged with whatever you’re noticing. It is what I call ‘interpersonal mindfulness.’ ”

That is something that Chester Elton, a best-selling author who’s been dubbed “the Apostle of Appreciation,” would endorse. As Elton says, “I have always appreciated leaders who were not careless in their relationships. And what I mean by that is, and this comes back to being mindful, is that it always bothered me when senior executives would blow off your appointment or would start late or come in late and they were just careless with your time. They didn’t get back to people. They didn’t keep their appointment. And, of course, the higher up you are, you’d say this guy’s the president, this guy’s the CEO, he’s got a lot of things going on. Yeah, but the message is very clear of what my value is when that leader is careless with my relationship. And I found in particular those were reasons why people leave.”

A leader is the public face of his team or organization. As such, the leader is always on stage, so his actions have consequences. Elton says, “Great leaders have to be mindful that their decisions have a ripple effect and that even casual comments can cause huge ripples throughout the organization.”

Motivating others, says Elton, is all about being aware of their thoughts and feelings. “Motivating others is all about asking, ‘What’s most important to you?’ Then use [that information] to make sure that happens. For example, for some people their motivation is family. So anything you could do … to get them home earlier or let them take a spouse on a trip, works really well. Other people are just ridiculously ambitious, so you couldn’t give them enough work and want to do as much as they can to be noticed.” Sheridan provides a good example of being mindful of the here and now and what it means to people and the organization. For example, as Sheridan notes, he found dirty dishes in the office’s kitchen sink. “Why am I paying attention to that? Because to me it’s indicative of a team whose members may not be respecting one another by leaving dishes for others to clean. And as the leader I have to watch for those little things as well because those are the things that will really knock you down over time.”

What Sheridan is getting to is what we call situational awareness.

Situational Awareness

Another form of mindfulness is situational awareness. This is knowing where you are and what you need to do next. Those who play sports well typically excel at situational awareness. They know where the opponent is and what they must do to make their play. In games like hockey, soccer, and basketball, players shift constantly from offense to defense and back again, depending upon ball control. The difference between offense and defense is more defined in baseball and football, but once play begins, assigned roles could change in a heartbeat.

Perhaps the game that provides the clearest version of situational awareness is golf. Golfers play the shots they hit. With each stroke, a golfer must consider the angle at which the play rests (the lie), the depth of grass (fairway or rough), and the terrain (sand traps, swales, and trees). Depending upon the conditions, including gauging wind direction, the player chooses the best club for the situation—a driver off the tee, long irons for long fairway shots, and short irons for close-in shots. More importantly, the golfer needs to know his abilities; that is, he needs to know which club is best for his position and his capability. Situational awareness, coupled with self-awareness, is critical to playing well.

Situational awareness is paramount in managerial situations. Managers need to ask themselves what is going on, or not going on, in their departments. The manager needs to know what resources she can share with her team. And most importantly, she needs to evaluate the skills and talents of her team.

The spectrum of available resources—both company resources and team strengths and weaknesses—form the backdrop to situational awareness related to challenges the team is facing as well as the roadblocks it faces. Let’s say the team is in human resources and has been asked to develop a new recruitment program. Using the popular SWOT method, managers consider the strengths of the company as well as its weaknesses, including opportunities for growth and threats from inside or outside.

Emerging from this analysis is the knowledge the manager needs to assign the right people to the right jobs, so she can develop a program that targets candidates who will fit the needs of the company now and, perhaps more importantly, in the future.

Understanding the situation comes from asking the right questions. As CEO of Campbell Soup Company, Doug Conant and his team focused on “listening before leading.” Doing so is not as easy as it sounds. In the press of business, as Conant explains, executives are pushed to make decisions out of a sense of expediency with “quick judgments.” The challenge, as Conant explains, is to slow down and let things settle a bit. Conant is fond of the Stephen Covey mantra “Seek first to understand and then to be understood.” Learning the situation then becomes fundamental to developing strong situational awareness.

State of Mindfulness

A good example of situational awareness on a macro-level scale might be Jerry Brown, governor of California at the time of this writing. In the 1970s and ’80s, Brown was nicknamed Governor Moonbeam for his big ideas and perhaps also for his lack of organizational prowess in getting them done. With his handsome looks, he dated A-list celebrities like Linda Ronstadt and Natalie Wood. But by the mid-1980s, Brown’s political career seemed to be over, and he was viewed as an afterthought.

Now in his mid-seventies, Brown is serving his second stint as governor (in his third term) and Bloomberg Businessweek dubbed him in a 2013 cover story “The Real Terminator.” The title refers to Brown’s success in reducing California’s debt and restoring its fiscal integrity. (His predecessor, Arnold Schwarzenegger, was unable to achieve those results.) Brown’s fiscal mastery, as detailed in Bloomberg Businessweek by Joel Stein, involves demonstrating the problem to the electorate and then dramatizing the effect of the failure to act.7 The more you think about it, the more remarkable the transformation becomes—Brown, a man well-known for his liberal political positions who could have made many happy by sniping from the sidelines, stepped up when he thought no one else could.

Brown’s rescue plan was born of crisis. When he took office in 2011, the state was $27 billion in debt and had the worst credit rating of all fifty states, according to Standard & Poor’s. Unemployment was 12.4 percent. California was in rough water. Brown leveraged this proverbial burning platform to look for solutions that would avert catastrophe.8

Longtime friend actor Warren Beatty said, “Since he has been chief executive of [California] twice, he has achieved a level of wisdom about the realities of the various conflicting forces that very few people have been able to achieve.” Such awareness comes from Brown’s deep intellect (he entered a Jesuit seminary, though was not ordained, and has studied Buddhism) and his commitment to doing things that matter now. Brown made deep cuts to social programs that antagonized liberals, but he also raised taxes slightly, irritating conservatives.9

In 2013, unemployment dropped to 9.4 percent and the state posted a surplus of $850 million. California still faces a huge pension liability of more than $77 billion for state employees, so there is work to be done, but septuagenarian Brown views his role as one that entails creating a path to the future by doing things differently. Or, as he says, “There has to be drama … we’re on the stage of history.”10

As lofty a role as Brown sees for himself, he harkens back to his great-grandfather, August Schuckman, who migrated to California in the 1850s. A rock from the property Brown inherited sits on the coffee table in his modestly adorned office. Brown says, “When [Schuckman] came out here, you got your hands in the dirt, you got some people to work with you.” That is the approach Brown applies to fixing California, one that is more people-centric than “state-centric.”11 Such practicality affirms Brown’s grounded approach to governance.

Brown, like Mandela, is a mindful soul. In our exploration of mindfulness, we can see how these leaders use it to their advantage—to awaken people to an issue and then find ways to stir them to take positive action.

Situational awareness is essential to leadership, because it focuses the leader’s attention on what is happening. More specifically, it focuses the leader’s attention on what is happening with the team. In my career, I have seen leaders go out of their way to keep in touch with their people, whether they are across the hall or across an ocean. They know it’s essential to listen and learn how other people see issues, and also to understand how they process work flow, tackle challenges, and achieve success.

“No plan survives first contact with the enemy,” wrote Prussian general Helmuth von Moltke. Echoes of this thought have been put in many different forms because it captures the challenge that leaders face when they act upon their ideas or their strategies. “Work the plan” means more than follow directions, it means observe what is happening, listen to what people are saying, and then change accordingly, if necessary. A mindful leader will put himself into a position where he can watch what’s happening and listen to what others are saying.

Mindful Leadership

In Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln, the opening scene features President Lincoln (played by Daniel Day-Lewis) on a battlefield somewhere in the rain listening to what black soldiers are saying. Whether this exact scene ever occurred, it was typical of Lincoln, a humble man, to meet with soldiers as well as the common folks (as he was one himself) to listen to their stories and gauge from their words how they thought about the war or issues of the day.12

Ryan Lance, CEO of ConocoPhillips, the world’s largest independent exploration and production company, is noted for the time he spends with his employees. Throughout his career, starting out of high school as a roustabout and roughneck on oil rigs, Lance has used interaction with fellow employees to learn the oil and gas business at every level. Today as CEO, he regularly visits facilities throughout the world, from Alaska’s North Slope to Australia’s gas fields near Brisbane. He considers these visits a form of mindful leadership. “It’s a way to really take stock of the situation before you react or make a decision.”

Additionally, mindful leaders share their presence. That is, they let people know who they are and what they stand for. “I think most people want leaders who don’t overreact and aren’t impulsive,” says Lance. “If you want to stay in touch with the pulse of the company, you need to know what’s really going on. You need to hear what people tell you, but then you also need to know what’s going on behind the scenes. I believe that good leaders have that sense of calm, or what I refer to as quiet confidence, and most people want this from a leader. So mindfulness is a trait of that quiet confidence.”

For a busy executive, mindfulness requires practice and adherence to principle. As Lance says, “You’re always going to get pressure to deviate from your strategic intentions. You have to be mindful of the elements of the present situation that are trying to distract you from the strategic vision or objectives you have in mind, and you really have to provide a sense of consistency for the organization. They need to see that you’re still executing relative to your strategic objections, even as you react to the current day-to-day changes in the business environment.”

Mindful Future

Psychiatrist and executive coach Mark Goulston references a quote by famous psychoanalyst Wilfred Bion, who said, “To be present is to listen without memory or desire.” What Bion meant, as Goulston explains, “is that when you listen with memory you have an old personal agenda and you’re trying to plug people into it. And when you listen with desire you have a new personal agenda that you’re trying to plug people into, but you’re not really in touch with them.”

Mindful leaders do not have agendas, according to Goulston. They focus their messages and themselves on a vision and mission for the organization that is so compelling and appealing that it enrolls people spontaneously, and they want to serve that. Toward that end, Goulston favors what he calls “moon mission.” Borrowing from President John F. Kennedy’s call to action, Goulston says, “A moon mission has four components. The first is there has to be a date to it … as Kennedy said, before the end of the decade. Second, it has to be something that people can visualize. We’re going to put them on the moon and get them back. Third, it has to be a grand idea. And fourth, it has to be impossible right now.”

Power to Persevere

Mindfulness shapes a leader’s character. And, when called upon, leaders put their character into action. A stunning example of such character is the story of Judith Tebbutt, a British mental health social worker, who was captured by Somali pirates in September 2011 while on holiday in Kenya. Her husband was killed, but Tebbutt was used as a bargaining chip for ransom.

Her memoir of the experience, A Long Walk Home, details how she kept physically and mentally active during her six-month captivity. In an interview with Dan Damon of BBC World Service she detailed how she persevered. Tebbutt said she wrote A Long Walk Home to provide inspiration for other hostages: “Do not give up hope, you haven’t been forgotten.” The lessons she shares, however, are applicable to anyone seeking to hold onto their values and convictions in the face of poor odds.13

Tebbutt considered herself fit, so when she was first put into what she termed “the Big House,” where she was held captive, she paced out the dimensions of her room and walked her room on schedule—every half hour during daylight. She also did Pilates, to the dismay of her captors.

Tebbutt also engaged her mind. She sat regularly on her bed and imagined herself driving through the countryside in Cumbria, the part of England where she is from. She was given a small radio, which she used to listen to BBC World Service. “I was sitting in a very dark room listening to you,” she told reporter Dan Damon. “You have no idea what that means to me.”

Part of her strategy was to learn some of the Somali language so she could communicate: “Even though I despised these people, I knew that if I was going to be in their company for any length of time, I needed to try and build a rapport with them.”She also smiled at them. Her guards tried to make her wear full Somali dress, and when she did for the first time they complimented her as “Beauty Somali woman.” Tebbutt rebelled and did not acquiesce, adopting only the hijab. “I felt suffocated covered in all these robes,” she said.

Identity is critical to self-preservation. Tebbutt cautions that you cannot “lose your own identity. However cruel they are to you, however they degrade you, you must remind yourself of who you are all the time. I was still Jude.” During her captivity Tebbutt was also looking forward. “I wanted to come out [of captivity] as Jude. I wanted to find a life for Jude again.” Even though she lost her husband tragically and was deprived of her liberty, Tebbutt is not consumed by a need for revenge. “I don’t want [my captors] to have power over me.” Therefore she thinks of them on her own terms—when she wants to, not because she must.

The experience that Tebbutt endured is an extreme example, but her lessons in mindfulness serve to remind us that we can, when we apply ourselves, keep our minds active even in hardship. Such a lesson is important to remember because leaders face hardships daily, and while most of these hardships are not physically threatening, they feel overwhelming. The challenge is to keep mentally sharp and do as Tebbutt did—maintain perspective on the situation. It was a strategy that enabled her to endure and it can help leaders adapt.

Mindfulness is an approach to leadership in which the leader is focused not only on the moment, but also on the people in that moment who will affect the future of the organization. Mindful leaders are engaged and their engagement sets the example for others to follow.

Mindful Intentions

Situational awareness, as we saw with Lincoln, is a matter of engaging with others. However, it involves more than people-engagement. It requires an ability to engage one’s own self. Again, Lincoln serves as a good example of a man in touch with himself. Although he was deeply fatalistic (and had premonitions of his own death), he knew what he was capable of doing. His humility was dumbfounding at times. As we know from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s biography Team of Rivals, Lincoln peopled his cabinet with political figures who had opposed him. He admired the talents of these men and knew that the only hope of repairing a divided nation was to bring people, including those who disagreed with him, together to work for a common cause—the healing of the Union.14

Lincoln’s ability to tolerate dissent and to work with people who were his enemies was rooted in his character (we will explore more about character in chapter 3). “Mindfulness is very much rooted in character,” says Donald Altman. “Actually, if you go back to the ancient history of mindfulness, you will find the four foundations of mindfulness. One of those foundations is ethics and values.” For Altman, mindfulness helps us re-invigorate our values because it helps us live and lead more intentionally and more purposefully. According to Altman, “Companies have mission statements about what’s important to them. And as individuals we need to have intention statements for our careers, intention statements for friendships, for our personal health, and our emotional well-being. When intentionality is connected to our values it becomes our personalized steering wheel. It helps turn us in the direction that we want to go. And if we’re getting off track in some way, our sense of intention will help guide us back.”

Altman suggests that individuals develop a three- or four-sentence intention statement. He invites people to ask themselves: “Do you want to have a career where you are open with others, producing something of value, showing respect, putting in the best effort you can in that job?” While the process can be time-consuming, it helps focus the mind and spirit on greater goals. As a reminder of intention, Altman suggests, “Have people carry that intention statement with them and to see are your actions—are your daily behaviors and actions consistent with that three- or four-sentence intention statement?” Mindfulness rests upon a foundation of intention, a willingness to look at the present with the commitment to make things better for others. Mindful leaders are cognizant of their own shortcomings but also have the humility to acknowledge them and the street smarts to leverage their strengths.

Closing Thought: Mindfulness

While mindfulness originates from within the individual, the practice of it puts the individual, in particular the leader, front and center of what is happening in the here and now, and it helps her focus on what may come in the future. A mindful leader is aware of the situation as well as of how people on her team will react to that situation. As such, a mindful leader is vigilant but also attuned to the inevitable forces of change. Mindfulness, then, prepares leaders to focus on the present as well as prepare for the future.

Mindfulness = Awareness + Intention

Leadership Questions

- What gets you up in the morning and why?

- How do you prepare yourself to engage with the world?

- How often do you make time to ask yourself what is happening, what is not happening, and what you can do to influence the outcome?

- How well are you succeeding at doing what you enjoy most?

- What will you do differently to ensure that you keep working at your best?

- Are you making time to reflect on what you have done? What are your thoughts about what is working and what is not working? What changes will you make?

Leadership Directives

- When you are mindful, you must be fully in the moment. Mindfulness commits you to being fully aware, fully engaged, fully committed.

- Identify what you like to do, what you are good at doing personally and professionally. Consider why you like doing these things.

- Make a list of the things you like about your work. Be as specific as you can.

- Make a list of things you do not like about your work. Be as specific as you can.

- Understand that what you like about work may be the hardest thing that you do, but from it comes the greatest satisfaction.

- Look for inspiration in the actions of those you admire. Ask yourself how they do it and how that might apply to you.