Remaking History

The Brothers Lumière and the Motion Picture

Make the mechanism that put the movies on the big screen.

Written by William Gurstelle ![]() Illustrated by Rob Nance

Illustrated by Rob Nance

Time Required: A Few Hours

Cost: $10–$20

WILLIAM GURSTELLE is a contributing editor of MAKE. The new and expanded edition of his book Backyard Ballistics is available in the Maker Shed (makershed.com).

Materials

» Plywood or hardboard, ¾": 5½"×8" (1) and 5½"×5" (1) for stand ![]() and prop

and prop ![]()

» Plywood or hardboard, ⅜": 3½"×3½" (1) and 2"×2" (1) for follower ![]() and cam

and cam ![]()

» Wood dowels, ¼" diameter, 2½" long (2) for follower’s pin ![]() and claw

and claw ![]()

» Wood dowels, ⅜" diameter: 1½" long (4) for axle ![]() , cam crank

, cam crank ![]() , and pin guides

, and pin guides ![]()

» Wood glue

» Clamps

» Paint (optional)

Tools

» Jigsaw

» Drill with ¼" and 3/8" bits

» Sandpaper or file

» Safety glasses

CONTROVERSY SWIRLS ABOUT WHO MOST DESERVES CREDIT FOR INVENTING MOTION PICTURES — Thomas Edison, Eadweard Muybridge, Étienne-Jules Marey — but a good case can be made that French brothers Auguste and Louis Lumière were the fathers of the modern movie. The experience we get at the local multiplex is due, in large part, to this brilliant pair.

The Lumières were born in Besancon, France, in the 1860s. Their father, Antoine, was a well-known portrait painter and manufacturer of photographic equipment. In 1894, Antoine saw a demonstration of Edison’s kinetoscope, an early motion-picture player. He was impressed; not so much by the technology, but by the potential for an entirely new entertainment-based business.

Excited by their father’s vision, the brothers took up the challenge of building something that would provide a better, more immersive experience than Edison’s peephole. If moving pictures were to become popular, they believed, the image had to be projected on a large screen. Not only could many people watch (and pay for) the movie at one time, but the experience would be bigger, grander, and more exciting.

They moved with astounding speed, designing and patenting their device in 1895. The Lumières’ cinématographe was compact and lightweight, a mere 16 pounds. It used a simple hand crank instead of the kinetoscope’s heavy, noisy, and expensive DC electric motor. And most importantly, it was a bona fide projector, able to throw a moving image onto a large screen. In March 1895, the brothers screened a 47-second film for a Parisian audience. The Godfather it isn’t, but it was a world changer.

The Cam-Controlled Movie Projector

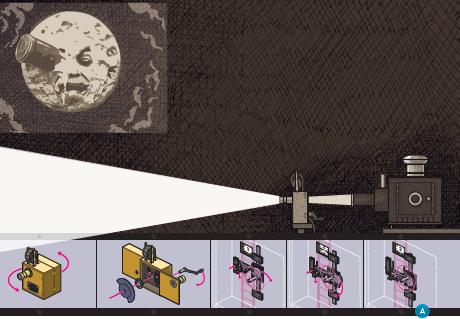

The cinematograph did a lot of things much better than the praxinoscope, the kinetoscope, the mutoscope, and the other motion-picture machines that preceded it. Its most important technological advance was the use of a sophisticated mechanism called an eccentric cam to position a single frame of the film stock in front of the projector lens, hold it there for ![]() second, and then quickly advance the film to the next frame (Figure A). By cranking at 2 revolutions per second, the projectionist moved the film at 16 frames per second, providing a smooth, realistic depiction of motion, perfect for films of factory employees leaving work, babies eating crackers, and other popular turn-of-the-century storylines.

second, and then quickly advance the film to the next frame (Figure A). By cranking at 2 revolutions per second, the projectionist moved the film at 16 frames per second, providing a smooth, realistic depiction of motion, perfect for films of factory employees leaving work, babies eating crackers, and other popular turn-of-the-century storylines.

Rotary cams are among the most important mechanical mechanisms. They’re in cars and trucks, machine tools, sewing machines, and myriad other technologies. Their main purpose is to translate rotating motion into linear motion. Typically a spring is used to keep a part called a follower in sliding contact with a rotating disk called a cam. As the cam turns, the follower traces out a programmable up-and-down motion based on the shape of the cam.

In their projector, the Lumière brothers designed the cam follower to completely enclose the cam. No spring is necessary to maintain sliding contact; the mechanism works in any direction or orientation. The follower is connected to claws or pins that grab the movie film by its perforations, advance it, then release it. This method provides a smooth and dependable method of moving, pausing, and advancing film. See it in action at makezine.com/go/lumierecam.

Make a Lumière Cam and Follower Mechanism

This project is fun to make, and you’ll get an interesting desk toy out of it. When you turn the crank, the claw moves with a peculiar motion that you can adjust by making small changes in the profile of the cam.

1. Cut the cam follower

Don safety glasses and use a jigsaw to cut the 2"×2" square opening centered in the 3½"×3½"×⅜" follower piece. Sand the interior surfaces; they must be smooth and free from nicks in order for the cam to slide easily inside the follower.

2. Attach the pin and claw

Drill a ¼" hole ½" deep in the exact centers of the upper and lower ends of the cam follower. Add a drop of glue to each hole and insert the pin and claw dowels. Let dry.

3. Cut the cam

Using Figure B as a guide, use a jigsaw to cut the cam. Sand it smooth, then test-fit it inside the follower — the cam should rotate completely, without any binding or interference. If binding occurs, note where it takes place and use sandpaper or a file to trim the cam until it turns smoothly.

4. Drill the cam

Drill 3/8" holes through the cam as shown, for the axle and the crank. Enlarge the axle hole to ![]() so the cam can spin freely.

so the cam can spin freely.

5. Make the base

Drill a ⅜" hole through the base, centered 2¾" from the top, and another pair 2¾" below it, centered 1" apart. Glue the axle and the pin guides into the holes. Glue the prop to the back of the base. Clamp and let dry.

6. Attach the crank

Glue the crank into the cam’s crank hole, making sure it doesn’t protrude out the back. Wipe up any excess glue and let dry.

7. Sand and paint

Sand all contact surfaces. The smoother the cam and follower, the better they work. Paint (if desired) and let dry completely.

8. Assemble the mechanism

Place the cam over the axle, and the follower over the cam, its pin between the guides.

9. Turn the crank and try it out!

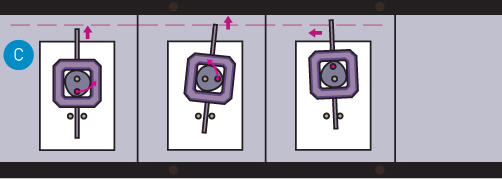

As you turn the crank counterclockwise, the cam follower traces out a repeating motion (Figure C) where the claw rises (engages the perforations in the film), moves to the left (advances the film), remains stationary a moment (“dwells” in engineering lingo), dips and returns, and then starts over. ![]()