So, Now You Are in Charge! Leading Your Team and Managing When Others Report to You

Chapter Overview

You are in a new role now with supervisory responsibilities. This requires you to transition from being a team member to the team’s leader. You need to establish credibility and earn the respect of others for new capabilities you are developing. You will need to treat others fairly and avoid granting special treatment to those who have been your friends. Mentors and peers can help you in your development so you do not have to figure things out all by yourself.

We will show you how to communicate your expectations for behavior and performance to help your people perform well. We also look at what you need to do when things do not work out and improvement is needed, or you need to fire people who report to you.

Topics in this chapter:

- What is different about being a manager

- Delegating responsibility to others

- Power and trust in your new managerial role

- Setting expectations and communicating them

- Accountability without fear and blame

- Expectation Management Model

- Performance expectations

- Coaching for performance and development

- Performance tracking and planning

- Performance problems: What to do?

- Chapter summary and key points

- Learning activities for this chapter

This chapter in Volume I focuses on how you get started in your new role with responsibility for managing others. Soon, you will develop more skills for creating a positive working culture, building a strengths-based team, selecting and hiring new people. For further information on these and other topics related to work culture, employee strengths, and hiring, please see Chapter 2 in Volume II.

What Is Different about Being a Manager

Congratulations, now you are in charge! What has changed for you in your new role? As Ginny Trierweiler, PhD, points out, “When you are a star clinician who is promoted to a manager position, you may go from being the most capable and successful on the job to being uncharacteristically unfocused and disoriented. If you are to become successful in your new role as manager, your top priority is to become clear about your new role and how it differs from your prior role as clinician.”1

Let us step back and consider how your strengths and skills helped you get to where you are now. Probably, like many of the managers interviewed for this book, you earned the credentials needed to practice and lead in your health care profession, accepted responsibility for getting work done correctly, and you sought opportunities intentionally to increase effectiveness in your team or larger workplace. Or perhaps someone else noticed your successful performance and appointed you to an interim role to fill a gap in management. Perhaps you recognize some of these actions and others we heard from those we interviewed and summarized in the previous chapter, and maybe you would emphasize some additional attributes that contributed to your success, such as your reputation for collaboration or talent for innovation.

Step Forward and Take Charge

“Effective leaders,” Armstrong (2013) writes, “are confident and know where they want to go and what they want to do. They have the ability to take charge, convey their vision to their team, get their team into action and ensure they achieve their agreed-upon goals.”2

These actions may require big changes that will stretch you in ways that are not always comfortable! Many of the people I talked with described their initial feelings as a new manager as treading water, learning to be comfortable being uncomfortable, realizing and needing to admit they did not know everything, learning who to ask and where to get information on handling issues they had not dealt with before, all while trying to act confident so the people they supervised would trust in the new manager’s leadership capabilities. Although they might feel disoriented, they knew it was not a good idea to admit aloud, “I don’t know what I’m doing!”

In surveys reported by Horstman (2016), many new managers in various industries described their experience like this: “I got promoted, and they didn’t tell me anything about what I was supposed to do or how I was supposed to do it. They just gave me a team and wished me luck.”3 It is no wonder that many new managers feel overwhelmed and underprepared! Let us start by identifying your managerial activities and clarifying your responsibilities to help you sort this out. Clearly understanding the new rules and tools you will be working with can build your confidence and success as a new health care manager.

What Do Managers Do?

Armstrong (2013) explains what management is and what managers do: “Management is the art and science of getting things done. As a manager, you are there to get things done through people . . . . You decide what to do and then ensure that it gets done with the help of the members of your team.” He further explains that people are the most valuable resource and that managers are ultimately responsible for the management of all resources.

As a manager, it is your responsibility to ensure that your people have the tools and support they need to meet the requirements of their jobs.4 This does not mean you need to be available constantly to answer every question and tell them what needs to be done; rather, you need to direct them and help them figure out where to get the information and skills they need. Often, you need to get actively involved in removing barriers to their work, especially because you have decision-making power, influence, and authority that they may not have access to in their positions. Your ensuring that they can be successful in meeting the requirements of their work is an expected part of your manager role.

Typical management activities include supervising people who report to you, using data and reports to monitor team progress on key performance indicators, leading meetings, planning and budgeting, hiring and ensuring successful performance of your staff, resolving problems that affect patient care, and handling barriers that interfere with individual or team performance.

Responsibility for the Work of Others

Essentially, you are responsible not only for the work you do, but also for the actions and results of those who now report to you. Christina Loetscher-Whetstone, BSN, RN, Director of Nursing at the Mental Health Center of Denver, described her new elevated level of responsibility as “worrying about 30 other licenses. It’s easier to worry about just me, but that’s not what I signed up for.”5

Horstman (2016) identifies four critical behaviors of managers:

- Get to know your people.

- Communicate about their performance by giving them feedback.

- Ask for more to stretch them and help them grow.

- Delegate, handing work down to the people who report to you.

We will look more closely at all of these items as we progress through this chapter. As you take charge, you will need to assign some of the things you were doing to the other people who now report to you, and be alert to when it’s appropriate to delegate activities rather than do everything yourself. Let us look more closely now at delegating, its benefits, and how to do it effectively.

Delegating Responsibility to Others

Delegating involves getting things done through other people. Although managers must delegate many activities to their team members, they still remain involved and accountable. As Armstrong (2013) observes, “You can’t delegate everything.”6

Horstman (2016) advises, “If you’re a manager, your key to long-term success is to master the art of delegation.”7 By delegating, you free up your time for work that only you can do because it requires your level of skills, experience, and responsibility. “Delegate, but you can’t abdicate,” warns Ruth King (2013). Even though you have asked someone else to perform the actual work, you still have responsibility for the overall results.8 So, there is more involved than just passing work to others and forgetting about it. There are some important things you need to establish to support the successful completion of the work and the development of the employee performing it.

When handled appropriately, delegation helps you lead more effectively by developing your skills to focus on the most appropriate and impactful things, and it builds the capabilities of the people who report to you and the overall value of your team’s contributions.

How to Delegate

Ensure your employee accepts and understands that the responsibility has been transferred to her, that she is committing to own it and complete the tasks. Horstman (2016) offers these guidelines:

- State your desire for help.

- Explain why you are asking that person to handle this activity. For instance, does she have special skills, or is the activity part of the responsibilities she has or wants to take on?

- Ask for specific acceptance.

- Describe the task or project in enough detail that she knows its purpose, status, what she needs to do with it.

- Communicate the deadline, quality measures of success, and reporting standards.

This model is based more on relationship power and persuasion rather than on role power and giving orders. When you request help, your employee could say no, but it is more likely she will say yes. This moves her energy from mere compliance to commitment, which makes her more energetic and effective.9

Here is an example of a conversation for you to delegate to your employee, following the steps above.

- “Carmen, before I became the manager, I was running the support groups for family care givers. I want our team to continue to do this because our patients’ family members need and value such support. I need help to make sure we provide the attention these people need.”

- “When I thought about who could handle this, I remembered you told me you enjoyed working with families, had extra training in group work, and wanted to offer more group resources for the people we work with.”

- “Would you be willing to take over running these groups and work with me to transition the responsibilities from me to you? What information and support do you need from me to handle this successfully?”

- “Currently I do the groups every Thursday morning. You’ll need to make sure the meeting room is scheduled through the end of the year, make sure patients have designated and approved our contact with their family members, and invite them. Here is my outline of what is covered. Please review it and meet with me to talk about what you’d like to add or change so you’re comfortable in how they’re covered.”

- “I’d like you to start running the group yourself in three weeks. Let’s schedule time in the coming week to review your ideas and plans. When you run the group, be sure to document who shows up and what was covered so we can submit for billing and track in our patients’ records for follow-up support. We survey group participants and review their satisfaction and feedback so we can ensure good quality. You and I can review the results in the first three months and talk about your ideas and suggestions.”

Helping Others Become More Effective

A manager’s job is to make others more effective so they can solve more problems, rather than all the problems coming back to you. As many managers explained in their interviews, this requires that you learn to trust your people and expect that their approaches will differ from yours. Chris Radigan, LCSW, admitted there was a challenge in letting go and allowing others to do things in their own effective ways.10 Jeff Tucker, VP of Human Resources at the Mental Health Center of Denver comments that delegation involves being satisfied with something different from the way you would have done it. He recommends giving people the objectives you need them to achieve and the parameters they have to work with, then expect them to achieve the results in their own way.11 In the example above, the manager asks the employee to think about changes and offers to help her plan to implement the changes effectively.

Freeing Up Your Time

In freeing up your time by delegating, Dobson and Dobson (2000) suggest that you find someone who already knows enough about how to do the delegated work so you do not need to provide much supervision on their handling of the task. Yet, a key reason to delegate is to develop the skills of others. Be prepared initially to spend more of your time and effort while the person is learning and the quality might not be up to what you could do yourself. Recognize that as a normal part of the learning and development process. “Provide the training, support, and encouragement over time to help someone grow and develop to the point that they can take on the assignment and make it their own.”12

In later sections, we will help you learn to coach the people who report to you so you can help them set goals. As you develop the habits of providing feedback and the routines to conduct coaching, you have the supports in place for you to delegate effectively. Later in this chapter, we will look at how you can communicate to earn the trust of others because they know what to expect of you and what you expect of them.

Power and Trust in Your New Managerial Role

Building a Foundation

Think about how you arrived in your new management role: were you promoted from within or hired externally? D.C. Dugdale, MD, reminds us to meet with each person. “Learn their pain points . . . . There is no substitute for face-to-face (interaction versus e-mail).” It is also important to recognize this main difference of situations between “A group that’s been waiting for a leader versus one that doesn’t think they need one.” You might need to build more groundwork with the latter.13

Using Power Effectively

Elvira Ramos, Vice President of Programs and Inclusive Leadership at the Community Foundation of Boulder County, describes effective use of power as a balancing act between being too soft and too tough. You need to make hard decisions and take responsibility for them. She suggests that sometimes you need to say, “Well, I’m the boss, and this is what we’re going to do.” She reminds us that as the leader, you do have power and it can be reassuring to staff; use it in a way that is kind and helps your team members do their jobs. And you are the one to take the heat for your team’s mistakes.14 Such interactions help build mutually supportive relationships between you and your team members to position your team to successfully achieve organizational goals.

Driving Action by Aligning with Values

You have the power to communicate vision and set direction. As a manager, you need to look up and out to communicate strategic vision that helps people focus on successful performance and cost-effective operations to make maximal use of the revenue and health care funding available, while you will likely have little direct control over the structure of the health care funding mechanisms and associated rules for administering them. This can require a tremendous amount of judgment and communication to balance external interests with the motivation and values of clinicians, who really want to help their clients. Applying their clinical values, training, and judgment may seem to conflict with external requirements.

Complying with External Requirements

Kristi Mock, LCSW, Chief Operating Officer at the Mental Health Center of Denver, recalled the challenges of operating under a class-action lawsuit in the 1990s that required major restructuring of clinical service teams and externally prescribed amounts of service hours that were closely tracked and strictly enforced by an externally appointed court monitor.15,16 Her steady approach in engaging and communicating with clinical teams kept them motivated to ensure clients received high amounts and quality of care. On the administrative side, she instilled high performance and accountability in delivering the required reports to state government officials. Her ability to manage and balance these different interests led to the successful completion of the terms of the class-action lawsuit and its eventual dismissal, along with an enduring appreciation among clinical staff for the value of productive allocation of their time to direct service activities that help their clients get better and ensure ongoing financial health for the organization.

Internal Operating Efficiency and Core Clinical Values

Jen Leosz, LCSW, VP of Clinic Services at Mental Health Partners, is another highly respected and effective leader who rose through the clinical ranks from a therapist providing direct clinical service to an executive management position overseeing clinical teams and senior clinical directors. When her organization needed to boost its operating efficiency to ensure its sustainable financial health, Jen wisely recognized and aligned with the clinicians’ core service values. Clinically trained people become therapists in community mental health centers because they want to help people lead better lives; they are not driven by a primary interest in financial issues. Thus, she explained to her clinical teams how increasing their productive time with clients led to increased availability for seeing more clients, which improved clients’ access to care and reduced delays in their getting needed treatment. Clinicians understood and supported this reasoning, and so they were able to appreciate how increased efficiency and financial health ensured sustainable access and services that would continue to benefit clients.17

Accountability and Feedback on Progress

As these examples illustrate, clinicians who transition from direct care to manager roles have opportunities to leverage their clinical skills and values. They apply their ability to get things done to a broadened scope that includes administrative and leadership arenas. In addition to setting direction for their teams and organizations, they develop abilities to motivate others, hold them accountable for performance, and provide feedback and coaching to help them succeed. Both Kristi and Jen obtained data and reports that they shared with managers and teams they were responsible for to set performance targets and provide needed supports for their teams to meet their goals.

Involving People to Enlist Their Commitment

Jackie Attlesey-Pries, MS, Chief Nursing Officer at Boulder Community Health, described nurse staffing and scheduling as a critical issue because of the need for continuous coverage for hospitalized patients. It is challenging for managers to construct schedules that ensure adequate coverage for patients and are perceived as fair and workable for clinical team members. She found it most effective to clearly communicate the coverage needs and scheduling goals, and then involve the clinical nursing staff in building schedules they could support.18

Craig Iverson, MA, offers another example involving a former peer-level teammate who had confided that he was not completing his documentation correctly. Now as that person’s manager, you need to hold him accountable. Craig suggested initiating an honest conversation with the person to acknowledge that you are aware of what he is struggling with and to ask for his ideas and commitment on how he plans to improve.19

Professional Relationships with the People You Manage

Now that you are a manager, what kind of relationships should you have with the people you manage? Is it okay to be friends with them? Consider that there could be times when you will need to address performance problems or even terminate people who report to you.

Several authors offer examples of why you should not be friends with the people who report to you. Horstman (2016) describes obligations of friendship, which contain foreseeable hazards for both the manager and the person reporting to her. For example, as the manager, you might be aware of and feel obligated to warn your friend about imminent budget cuts and layoffs that could affect him, or you might feel loyalty to protect your friend from being laid off and lean toward selecting someone else for elimination, leaving others with perceptions of favoritism toward those you are friends with.20

You need to be fair and not accept worse behavior from friends than from the rest of your team members who report to you. Dobson and Dobson (2000) suggest, “Focus on the difference between being ‘friendly’ and being ‘friends.’ Friendly behavior is positive, cheerful, courteous, interested behavior that need not be restricted to people who are actually your friends. Friendly behavior is showing that you are aware of and have concern for someone else as a human being. Stay aware of personal relationships and how they interact with professional relationships . . . . You don’t ever want to be unaware of the significance others may read into them.”21

Managing Resistance

It is not unusual for new managers to encounter some resistance and testing from their new supervisees, especially if they had worked together as peer-level teammates. Amanda Daniel, LPC, Program Manager at the Mental Health Center of Denver, shared an example of a new manager who found that a team member suddenly “forgot how to do” parts of the job, such as clinical documentation, that she had previously mastered. This seemed to be a test of the limits of what the new manager would tolerate.

The new manager approached this calmly and nonjudgmentally by talking to the team member about the expectations for completing documentation, verifying that she understood and had what she needed to complete the task correctly. The manager expressed confidence that the team member could competently perform the task, which she had been handling successfully in the past. This direct and supportive approach resolved the problem.22 In another example, an RN who progressed from charge nurse to a unit manager in a hospital reported that most of her team knew she was in charge—except for one person. She talked directly with that person to correct the problem immediately before it could grow into a bigger issue.

Acknowledging Others You Have Been Promoted Over

Shari Harley (2013) recommends that if you were promoted and now your former coworkers and peers report to you, you have an individual conversation with each of your new direct reports. Allow them to talk about what it is like for them to be reporting to you now, how that changes the relationship between you, and any disappointment they may feel if they wanted the position themselves. Being candid to talk about what people might be thinking and saying can earn you respect from those you now manage and helps strengthen your relationships with each of them.23

There are some particular challenges for some people who are promoted internally, especially if they end up in charge of people who trained them early on. David Bachrach, MBA, FACMPE/LFACHE, offers an example from an academic medical center, where someone promoted into the position of department chair might need to encourage a highly paid senior (tenured) faculty member to step aside. This would require understanding the person’s needs and handling them sensitively. Perhaps you could offer that the person will still be included in departmental activities and have a place to go, such as office space and access to libraries and resources. Then you would need to be direct and factual about what the organization cannot sustain, such as continuing to pay salaries at the same high level that people earned when they were seeing patients, teaching, and researching, because when they are no longer conducting those activities they are not generating the revenue associated with them.

On the other hand, if you were an external candidate, you may need to have a crucial conversation to acknowledge others who applied for but did not get the position you were hired into. Respect them and their needs, which could include looking elsewhere.24

Addressing Escalating Disrespect

So, what if you have followed the advice above, spoken directly with people who report to you, listened to their perspectives, yet problems persist or escalate? Some situations require swift and firm action from you. Patterson et al. (2012) recommend showing “zero tolerance for insubordination” or “over-the-line disrespect.” Speak up immediately to catch and address the escalating disrespect before it turns into abuse and insubordination. Tell the person what behavior you are observing, such as raising his voice or leaning toward you aggressively, and that it seems disrespectful to you. Let him know that you want to address his concerns about a content topic (e.g., staff scheduling), but it is difficult to do so when he is showing disrespect or other disruptive behaviors.25

If disrespect escalates to insubordination, get help if you need it from your human resources team, who can help you identify goals for the employee, create a specific plan, and stick with it. Make sure the plan for the employee’s improvement has benchmarks, timelines, and check-in points so it is clear whether the person is making the required progress or not. As Kathleen Winsor-Games advises, “Establish consequences and rewards and carry them out.” It might still be possible for the employee to work toward goals that are beneficial to your team and organization, so do your best to support that. But, if the employee decides not to cooperate, “be prepared to take the next steps, including termination.”26

Or you followed Harley’s (2013) advice and talked individually with your former peers who now report to you, and months later one of them is still resisting your managerial authority. You have had repeated conversations, and still she refuses to take direction from you and continues to ignore your feedback. What else can you do?

First, make sure you consult with your boss and human resources department and you have their support. Then, Harley recommends you open the conversation with your intention to talk about your working relationship. Remind the person that you have talked about how you want a good working relationship with her and your observations that she is still resisting you as her boss. Tell her the behavior has become a performance issue: the employee either needs to accept you as her supervisor or find another job. Allow the person to talk. Then end with a suggestion or request to let her know you would like her on the team if her behavior toward you changes; if not, the next step is a transition plan out of your team. This is an example of a challenging conversation that would be necessary to preserve your successful leadership of your team.

Similar situations occur when people have been given feedback repeatedly but nothing changes. In those cases, you need to continue to address the undesired behavior every time it occurs. Eventually, the person will tire of the conversations and either change or find a different position.27 Managers I have known have reported that they wished they’d had such conversations sooner because when they finally did, they experienced improved team functioning and improved their own performance with increased focus on important priorities.

Gaining the Trust of Others

Be aware and prepared to cope with resistance if several other people actively applied for the management position you were selected to fill. Sometimes the tension intensifies if you were hired from outside the organization and there were several internal candidates who were not chosen, and now they report to you. Winning them over can take some intentional effort and persistence as you work to earn the trust and confidence of those you supervise, practice dealing with conflict constructively, and become clear and direct to assertively face, rather than avoid, difficult conversations. In Chapter 1 of Volume II, we will look more closely at how to handle conflict. A good start is to listen to others and understand their values and viewpoints so you can encourage their involvement as you build your credibility and earn their support.

Setting Expectations and Communicating Them

Helpful advice about expectations was repeated throughout many of the interviews for this book and in our discussion above, about managing up: “Know your boss’s expectations of you,” and managing down: “Be clear in communicating your expectations for the people who report to you.” And, do not forget about the expectations of other people all around you!

Expectations for You and Your Team

A special characteristic of the health care industry is that the industry’s payment models and regulatory requirements are often based on safety and ethical concerns to prevent harm to patients. This extends the scope of external “customers” beyond the patient as the recipient of treatment services. So, in addition to internal organizational policies and goals, and the specific priorities of your boss, you and your team are probably accountable for meeting the requirements established by external organizations that pay for patients’ treatment and monitor for safety and effectiveness of these services.

Information is expected of you from insurance companies, public funding sources such as Medicare and Medicaid, and governmental agencies that directly oversee funding and service quality. Information such as clinical outcomes provides evidence of effective patient care and treatment. Other information reflects your team’s performance and compliance with the standards and requirements laid out in the contracts between your health care delivery organization and these administrative entities.

Table 2.1 provides an example of a brief, simplified set of requirements with representative items for illustration:

As a Learning Activity at the end of the chapter, you will have the opportunity to complete a table like this that represents the actual requirements and standards you are expected to meet in your organization.

Understand and Communicate What Is Expected of Your Team

It is important to make sure you have a clear understanding of the standards and contractual requirements you and your team are expected to meet such as timeliness of documentation, number of patients served in contractually specified categories, and content of documentation for specified events such as patient admissions, transfers, response to treatment, discharge, adverse incidents, and so forth. Depending on your position, you may or may not have direct contact with external site reviewers and auditors; those visits may be handled directly by your quality or compliance department, but in any case, you and your team are still accountable for supporting your internal colleagues who interact directly with external customers who monitor your organization’s performance to these standards.

Actively identifying these expectations and requirements up front can help you manage time and energy proactively. Your team members will appreciate the opportunity to plan and organize their time so they can deliver their best work rather than reacting to a barrage of short-notice requests to respond to external requirements that were not visible enough to be included in their planning and scheduling of the work they need to get done.

How to Communicate What You Expect

It is your responsibility to tell your team members the behaviors you expect of them and to make sure they know the performance requirements they are expected to meet. Of course, if you are proactive in establishing and communicating your expectations before problem behaviors arise, you increase the chances of your team members performing well and the people you manage coalescing into an effective team. To develop cooperation and commitment of your team members, remember to explain how expectations and standards support your teams’ goals and alignment with the organization’s mission. As many interview participants mentioned, it is important for them and their team members to understand why they are being asked to do things in specified ways.

Explain Why It Is Important

For example, adherence to correct formatting of monthly reports can seem like an annoying detail until people understand why it is needed. Typically, such reports are collected from a larger number of teams, results get synthesized and distributed to higher levels or to external audiences that can award rewards or impose penalties. And it is beneficial for the team to demonstrate to the organization’s executive team and board of directors the team’s valuable contributions to organizational goals. This helps your team earn a positive reputation for high-quality work to gain the support and resources needed for continuing success.

Be clear and specific when you communicate your expectations and intentions in areas such as the following.

Decision-Making Latitude

Tell the people who report to you what you expect them to decide for themselves, and at what level of financial expense or seriousness of a problem they need to ask for your approval. Examples:

“If you’re scheduled to be doing nonclinical administrative work and you need to be away from the clinic, you don’t need to ask my permission, but please let me know where you’ll be and how I can reach you if needed.”

“If you are with a patient who needs help beyond your clinical scope of practice, and the situation isn’t covered in our clinical protocols, or you aren’t sure of the best course of action, don’t struggle with this alone. Please contact me or our designated on-call senior clinician for guidance to determine what to do.”

“We have an allotted amount of bus tokens for patients who lack financial resources. Please use your judgment in offering them to those who truly need them. You may also authorize taxis for those whose insurance plans cover this. For noncovered transportation expenses, please ask me for authorization before charging the expense to our clinic’s budget.”

Standards and Due Dates

Tell people the standards for tasks and timing such as written progress reports and their format. For example, “Please send me a progress report of your activities by the 20th day of each month. Here is the format I need everyone to follow so I can review your input and compile what I need to send to our director and report to our compliance team for our facility accreditation and licensing requirements.”

Expected Levels of Performance

Find out and make sure your people know the levels of performance expected by the organization in key indicators such as patient satisfaction, health care measures such as HEDIS scores, percentage of time dedicated to direct patient services, cost measures, and other things measured by the organization that you and your team are accountable for delivering. When people know what they are expected to accomplish, and receive ongoing feedback on how closely they are attaining the established goals, they understand what their level of performance is, so there should be no surprises later when you conduct longer-term performance reviews with them.

Other Behavior

Be clear about the behaviors you expect in the workplace such as starting meetings on time, complying with company policies, notifying you and other team members of absence from work, supporting other teams when needed, and so forth. Many of these things are not numerically measured performance but you do observe when desired and required behaviors are happening, and when they are not. Clarifying such expectations supports accountability—how can people be accountable for doing something they did not know they were supposed to do? And when they did know but chose to not conform to expected behaviors, then it is fair for you to administer reasonable consequences.

Accountability Without Fear and Blame

We also need to set expectations for supporting a work culture which values doing the right things for the safety of our patients. It can be challenging for people to speak up when they are aware of errors or unsafe practices. On one hand, we need to be cautious about unduly punishing people for making honest mistakes. Maybe a nurse followed the required procedure, but got a bad outcome. Or something outside her control prevented a doctor from completing a procedure correctly. On the other hand, we cannot condone deliberate disregard of best clinical practices or deviation from company policies.

Fostering an environment of open communication, with the ability to look at mistakes without blame, can build trust within your team that leads to improvement in systems and processes supporting patient care. A surgeon described by Sutton (2010) reflected on problems he had experienced in his own medical training because of the harsh and disrespectful ways medical staff members treated those less senior. He concluded that “respect was important for reducing medical mistakes because nurses and residents need to feel safe—even obligated—to point out errors made by him and other senior physicians without fear of retribution.”28

For people to feel safe and empowered to speak up when they see things being done incorrectly that can adversely affect patient care, there must be trust and respect to identify problems and for people to feel confident that they will be listened to. Michael Ward, MD, led a roundtable discussion in a health care operations management conference in 2018, on how patient outcomes are impacted by coordination and communication within teams.29 In a conversation before his session, we talked about the importance he sees in empowering everyone on the clinical team to share perceptions openly, without regard to professional rank, so everyone’s input is listened to and valued in the context of the continuum of care for patients as they move through different areas of care delivery.

Fair and Just Culture

Consider the approach of “Just Culture” developed in health care organizations. Several of the nurse leaders I spoke with, such as Jackie Attlesey-Pries and Darcy Jaffe, champion it in their organizations,30,31 and Annette Cannon has presented a poster session about it in her nursing conferences.32 As they explained, it prevents medical errors and emphasizes accountability without unjust blame. In such a culture, people are expected to do the right thing. If they make errors or are aware of them, they are expected to be accountable by communicating and correcting problems. The emphasis is on high standards of care delivery to patients and being responsive to potential problems that get in its way. Trust and belief in people’s dedication to practicing responsibly and ethically de-emphasizes personal blame when often it is a system that is faulty. Of course, with accountability, health care practitioners do take responsibility for their mistakes and work hard to prevent and correct them.

Psychological Safety in the Work Environment

Frankel, Leonard, and Denham (2006) describe a fair and just culture as “one that learns and improves by openly identifying and examining its own weaknesses. Organizations with a Just Culture are as willing to expose areas of weakness as they are to display areas of excellence . . . . Each individual feels as accountable for maintaining this environment as they do for delivering outstanding care. They know that they are accountable for their actions, but will not be blamed for system faults in their work environment beyond their control . . . . They are accountable for developing and maintaining an environment that feels psychologically safe.” You play a key role in building such a culture in your organization when you ensure that every employee clearly understands her own accountability and you lead by example in practicing such accountability yourself. People feel respected by everyone in every work interaction they have.33

Reporting and Tracking for Quality Improvement

Your organization’s reporting practices for critical or adverse incidents can support your fair and just culture. Clearly communicating policies and expectations for reporting incidents instills accountability and shared responsibility among everyone for maintaining a safe and effective workplace. Categorizing types of incidents and tracking data supports systematic review of patterns and trends by objective committee members. Regularly occurring internal reviews should be protected from external examination to allow the organization to assess its mistakes honestly and openly.

Regular, systematic review of categories of incidents that occur frequently can shed light on opportunities for improvement to work systems. For example, medication errors might be caused by unclear labeling or packaging that are not necessarily the fault of the people administering the medications; however, these people should take responsibility for speaking up about their observations and experiences of what is not working.

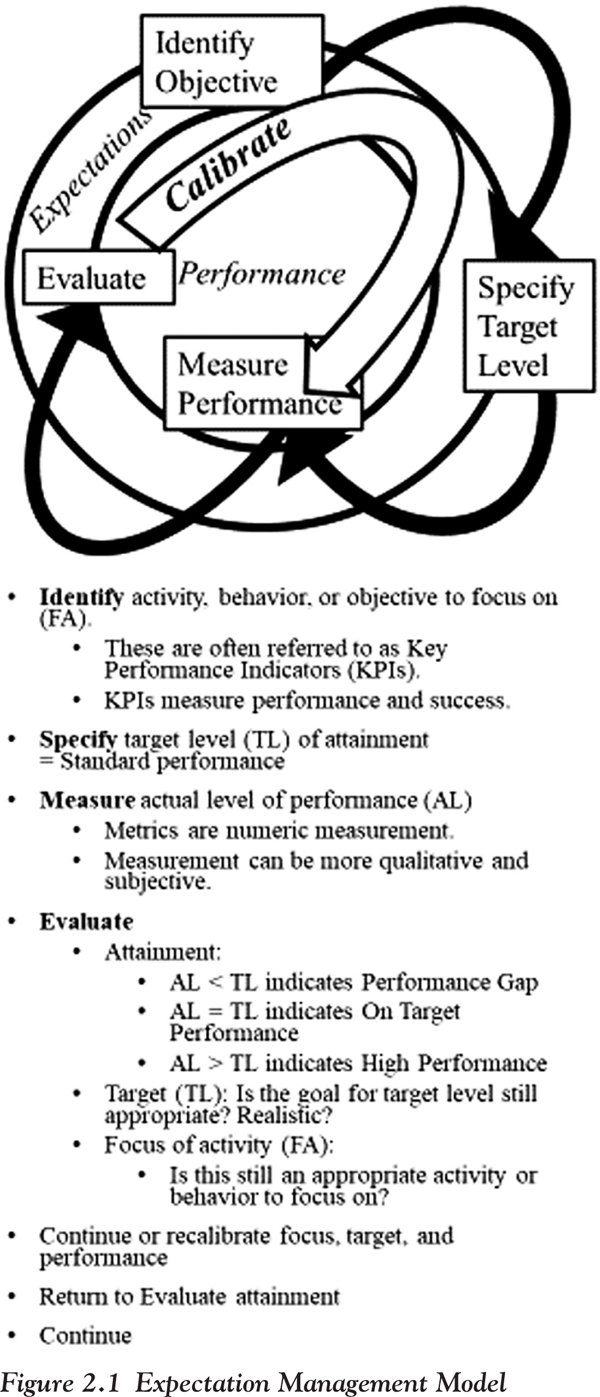

Patterns that show frequent errors by specific locations or individuals should be looked into to determine possible causes. Are there training issues, different procedures among locations, understaffing and overscheduling that affect error rates but are not within the control of the individuals making the errors? Or are there individuals making errors that they need to accept responsibility for correcting and avoiding? As a manager, it is helpful for you to focus on expectations and standards you need to hold people accountable for meeting, and help them get there. Figure 2.1 is an Expectation Management Model that shows how expectations drive performance.

The model shows expectations in the context of performance. The outer circle represents expectations, with actions to first identify objectives or behaviors that are the focus of work activities, and then to specify the target or desired level of performance in these objectives.

The inner circle represents actual performance, which will be measured and compared to the specified target or desired level to evaluate whether and to what extent the expectation has been met. Then calibration occurs to adjust performance, and recalibrate objectives and targets if needed.

Steps in Setting and Managing Expectations for Behavior and Performance

- Identify the activity, behavior, or objective to focus on. These can be the behaviors and activities you expect of your team members, or quantifiable Key Performance Indicators.

- Specify the target level of attainment. This sets your expected standards for performance. The target can be specified numerically or described in terms of desired observable behaviors.

- Measure the actual level of performance. This could be numeric (metrics) or qualitative and subjective assessment through observation.

- Evaluate whether the actual performance meets, falls short of, or exceeds the expected standard level. Also consider whether the target level is realistic and appropriate, not too easy or impossibly difficult, and whether the focus and objective are still appropriate.

- Encourage performance adjustment if needed, and recalibrate objectives and targets as appropriate.

- Continue to measure performance and facilitate adjustments as needed.

Example of Applying the Model

Community mental health centers across the United States require clinicians to spend a specified number of hours per month or percentage of their work time providing direct care and services to clients, as shown in Table 2.2. Each center establishes an appropriate standard that supports the organization’s generation of billable services to payers and ensures that clients and patients have timely access to the clinical care they need. Typical percentages of direct service time range from 60 to 75 percent of work time. This allows for necessary time for non-billable coordination, documentation, and administration that is necessary to support the direct care.

Notice how these steps support critical areas we covered earlier to communicate expectations and instill accountability for meeting them. Measurement and discussion about what is being measured helps adjust for fair goals that can realistically be attained. The open dialogue between managers and team members identifies opportunities for improving the quality of work and the systems, such as tracking and reporting capabilities, that support the people who are doing the work.

Performance Expectations

Define Performance Standards and Help Employees Achieve Them

Darla Schueth, RN, MBA, retired CEO and President of TRU Community Care, shared an illustration from her early experience as a new nurse supervisor conducting performance evaluations. Darla discovered that nurse Maria had a different view of her own performance than that of her supervisor, Darla, who needed to provide honest feedback in a way that would motivate rather than discourage her supervisee.

Rather than berate the nurse for her performance deficiencies, Darla decided to create a shared vision of good performance and communicate her commitment to supporting her employee’s growth and development by telling her, “You can be what you think you are and I will help you get there!” They talked and came to agreement about what good performance looked like, and Maria accepted Darla’s feedback on what she needed to improve, which was timeliness of documentation. “She owned it!” Darla reported, “And in six months she earned the raise we’d agreed to for her improved performance.”34

Word Pictures for Clear Understanding

Darla’s story reinforces advice from Mark Murphy (2017), who recommends that when we see things differently from others we work with, we start a conversation, not a confrontation, because confrontation only invites resistance. Conversation eliminates blame, can help to reassure the other person that you want to look at the situation to get on the same page, and opens the door to agreeing to a plan, which helps the other person feel in control.35

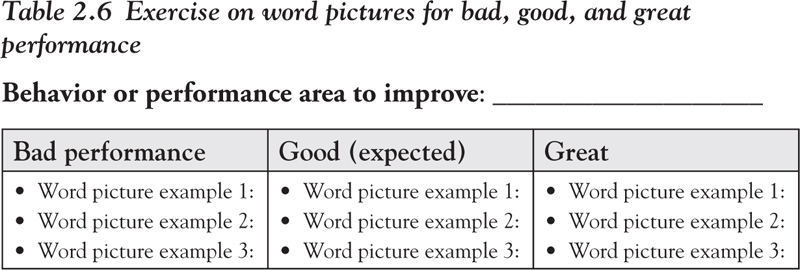

Murphy recommends making expectations completely clear to employees by creating what he calls “word pictures.” It is not enough to tell employees generally that they are not doing a good or good enough job; you will never close the assessment gap between your views and theirs if you have not identified exactly what subpar (bad), good, and exceptional (great) performance consists of. “A word picture is a shared definition that uses concrete language with examples of three levels (of performance): bad, good, and great.”

As Murphy explains, “When everyone has a different definition of the truth, an argument is virtually guaranteed. And far too many disagreements occur because we don’t have a clear and shared definition of the truth. A Word Picture . . . transforms abstract concepts into concrete examples that anyone can understand . . . . People understand abstract concepts faster and better with examples that teach how to do something well, how not to do something, and how to do that something incredibly well. It is also beneficial to use concrete words, phrases, and sentences, as they are found to be more comprehensive, memorable, and interesting than abstract language.”36

Use Relevant Examples of Standards

Show examples based on the standards most relevant to the clinician’s setting and responsibilities. For instance, in acute hospital settings the treatment team needs immediate access to current information about the patient, including brief but complete and accurate records of patients’ vital signs and readiness for discharge. Exceptional or “great” documentation might add other information, assessment, or cues that support excellent coordination and care delivery for patients, with helpful aftercare plans.

So, for clinical documentation, you could review with clinicians the specific standards for timeliness and content needed in the particular health care setting you work in. For example, some outpatient organizations require that all documentation of patient services be completed in the electronic health record within 24 hours of service and treatment plans need to be reviewed and updated every 6 months according to very specific standards. Show clinicians examples of “great” or exceptional treatment plans and point out what differentiates them from ordinary ones; perhaps the “great” ones show clear evidence of patient involvement and are designed to measure clinical outcomes efficiently.

Performance Scale Example

For example, in an outpatient clinic, you could develop agreements with the staff members who check in patients by comparing actions along a performance scale from bad to more helpful, as shown in Table 2.3.

Pick two or three illustrations in each column that are relevant to the employee and his job. An employee can identify where she falls along that scale and what she could do instead, or even how to make a strong performance even better. This approach can help when there are problems with areas that have not been defined specifically. A manager who wanted to get rid of someone because he has a “bad attitude” could reframe the conversation to focus on the specific behaviors that illustrate helpful or problematic attitudes when helping patients.

Examples of Measuring Performance to Standards

When you define what people are expected to do, and communicate the required amount or level to be achieved, you can measure their performance relative to meeting the established standards. Table 2.4 provides examples of what some interviewees have measured relative to standards.

Lucille explained how standards helped her manage performance. “When you’ve communicated what you expect and you’re consistent about not accepting excuses, people either improve in deficient areas or some choose to resign.”37

Performance Feedback

Now that you and your employees have clearly defined what high performance looks like, how can you help them perform at the desired high level? Most organizations require an annual performance review, according to a standardized format and approach. And it is common practice for new employees to have probationary periods for their first 3 or 6 months, with assessments to confirm that they are on track and making expected progress in learning and succeeding in their new positions. These formal assessments do provide the opportunity to provide feedback, recognize employees for their successes, encourage them to continue successful approaches, discuss needed improvement, and find out what employees want to develop and accomplish. But are they frequent and soon enough?

Feedback to Cultivate Development

Ken Blanchard and Spencer Johnson’s advice in an updated version of their ever-popular book, The One Minute Manager (2003), is to notice when people do things right and let them know immediately. Especially when employees are new in their roles, frequent positive feedback can shape their behavior in growing into the full competency they need to attain. The flip side is that you also need to let people know when they do something wrong, in a constructive way that lets them know you believe in them and support their success.

These authors recommend that you criticize the action and support the person in a way that helps him get on the right track. The idea of being a “one-minute manager” is to do such high-impact things in a focused and succinct way. Because you do not need to schedule long conversations, you can more easily conduct these conversations briefly and promptly.38

Dale Carnegie (1981) recommends you offer praise and sincere appreciation to other people. If someone who reports to you makes a mistake, Carnegie recommends that you allow him to save face. Use encouragement so the person has confidence in his ability to correct deficiencies or mistakes. When you understand the motivations of other people, it helps you enlist their cooperation and commitment to doing what you suggest, particularly when you are asking questions to elicit ideas rather than giving orders.39

Your noticing and communicating with the people you supervise about both their successes and areas that need improvement signals to the people you supervise that you care and are invested in helping them to be successful. When you do this frequently, immediately, and supportively, you foster your employees’ development.

Be Clear and Specific

When giving feedback about performance, it is important to be specific so the person knows exactly what she did well or needs to improve. If you merely mention to an employee, “You’re good at making people happy,” she does not know much about what she is doing well, whether you are referring to coworkers, patients, or others. She might be wondering what you have seen and appreciated and might be less likely to repeat what she actually did that you found so effective because she really does not know what it was.

Notice the difference in saying this instead. “Kirby, I appreciate the way you worked with Mr. Dansky when he complained about his son’s treatment. Your listening and compassion were exactly what he needed and you turned a detractor into a strong supporter of our organization.” Now Kirby knows what she did, how it was helpful, and why it is important, so she will be more likely to repeat the valued behavior and develop further skills in that area.

Being specific is also helpful when you need to provide feedback on what the employee did not do well. Rather than telling an employee, “Your communication skills need improving,” the employee will be able to take more effective action to improve if you open a dialogue with your specific observation such as, “I noticed that when you talked to the housekeeping supervisor about the way rooms were being cleaned, she looked upset and sounded angry.” This lets the employee know exactly what problem you are addressing and opens the door to constructive conversation about what she could do to improve in that specific area. You may be able to help with further coaching and interaction with your employee to help her identify and practice more effective ways of expressing her concerns to others.

Coaching for Performance and Development

What is Coaching?

As a manager, you will meet regularly with the people you supervise to help them when they have questions, ensure they are progressing and performing as required, and to coach them for their growth and development. Some of the time you spend with them will involve reviewing their progress and accomplishments in their job responsibilities, often by looking at numerical measures (often referred to as “metrics”) in key performance indicators (KPIs) and helping them determine what and how to improve. This includes data and reports on their productive time providing direct care to patients, adverse incidents and errors, patient satisfaction, results of internal and external reviews of their documentation, patient outcomes, length of stay and time to discharge, and so forth.

Be sure the standards and targets are clearly quantified as much as possible to ensure you and your supervisees agree to performance goals and expectations. Such regular and objective work together is important for keeping people motivated, developing as needed, and avoiding unpleasant performance problems later on.

Coaching also involves helping your employee develop skills and manage behaviors that can help her advance or get in the way if she needs to adjust them. Behaviors requiring change could involve things like absenteeism, lateness arriving for work or meetings, or interrupting others. Behaviors that can be helpful for the employee to develop include things like volunteering to help out when needed, taking initiative to start projects, developing confidence in communicating and doing presentations, and speaking up in meetings.

Skills could be technical skills such as working with software, data analytics, writing, and other knowledge-based work that a coach probably would not teach the employee directly but would help the employee find and access appropriate resources for learning, and then follow up to check her progress.

Why Is It Important?

Billy Carestio learned from the great leaders who mentored him that developing people involves translating and coaching, not just demonstrating what to do. “Know where folks’ comfort levels are and where their Achilles heels are,” he advises, to help people find their way. Now as Director of Nursing at Mental Health Partners, his focus is, “How to get people to bring their A-game every day,” as he facilitates his team members in delivering their best work.40

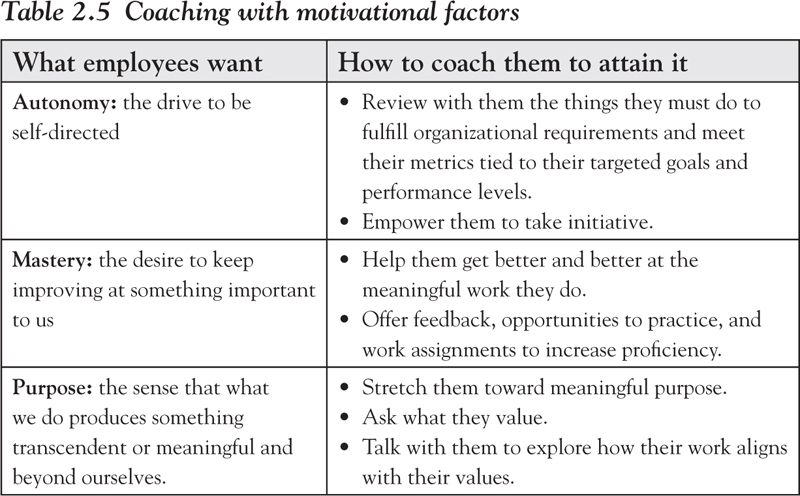

Ideally, coaching fosters employees’ development and commitment to the organization by helping them articulate and achieve their dreams. Everyone gets into his line of work for his own reasons. Author Daniel Pink (2009) provides insights on people’s motivation that can help you understand what drives your employees. What they want is:

- autonomy, the drive to be self-directed;

- mastery, the desire to keep improving at something important to us;

- purpose, the sense that what we do produces something transcendent or meaningful and beyond ourselves.

Of course, compensation is important, but it is not all that matters in retaining your people and keeping them feeling satisfied with work. Pink explains that after people are paid enough to take the issue of money off the table, they are not thinking about money and they are thinking about work; then the three things above have been shown through scientific research to lead to better performance.41

How to Coach

The ideal approach to coaching your employees helps them understand the things they must do to fulfill organizational requirements, meet their metrics tied to their targeted goals and performance levels, and fulfill other expectations for their behavior. You could organize your approach to align with the motivational factors identified by Pink, as described in Table 2.5.

Coaching offers the opportunity to ask your employees what they aspire to achieve and attain, and to help them prepare and develop the skills to succeed in increasingly responsible positions.

Effective coaching is not just about providing answers but involves asking questions to empower employees to discover answers and commit to actions to attain what they identify.

The coaching role you play is vital because your constructive guidance, feedback, and recommendations help your team members develop, stretch, and increase their abilities and effectiveness. “Clinicians are helpers,” Jen Leosz, LCSW, explains. “Supervising isn’t just about giving answers—empower the person you supervise to come up with answers.” For example, an organization may value high productivity and expect clinicians to see as many clients as possible. It takes initiative to fill a schedule. As a manager, you must show people how to do things in new ways and allow them to experience it. Give them choices on how they accomplish it, with room to try new things.42

Tina Howard, LICSW, recommends helping supervisees shift their perspective from micro to macro and vice versa. If they are looking at many things or too big a picture, help them focus on one strategy they can actually take and apply. Other times, reframe and help them broaden the possibilities. For example, in a school counseling situation, a therapist might be focusing on a student’s autism but maybe that is not the only or even key issue. Help them see other possibilities.43

When to Coach

David Bachrach, MBA, FACMPE/LFACHE, a consultant who provides coaching to department chairpersons in academic medical centers, has been called in to address a problem described as, “We have a chair who’s failing.” Unfortunately, there’s a stigma associated with coaching after the failure is evident. He turned it around to building a foundation for people to succeed by building coaching into their onboarding plans rather than requiring rescue after failure, so now in the centers he consults with, leadership coaching is part of the package when someone is offered the position.44

You, too, can be proactive in building a foundation for success with the people who report to you. You should schedule regular time with all your employees for ongoing coaching. This is where you talk about their goals, progress, and performance. If you have recent feedback that you have not had a chance to share with them, you can do it during these meetings. This is when you review the metrics relevant to their position and how they are doing. If they need something to help them be more successful—such as tools, training, support from you, or your guidance—you may provide that. A lot of your time in coaching should be spent in listening to your employees, asking them questions, talking about what they need to do to succeed and considering how you can help them.

Coaching and Supporting Your People

Sometimes you will also support your people by advocating for them to rise to expanded responsibilities, or by advising them and supporting them in moving to an alternate track that positions them for long-term growth in alignment with their goals and values. In Volume II, Chapter 2, we will look more closely at how an organization created a workplace culture that helps employees realize their dreams and potential, and how to measure and leverage the strengths of the people on your team. In the next section, we will look at an example provided in an interview about a manager’s early experience in her new position managing a longer-term employee.

Coaching for Employee Development: An Example

A situation was described in one of our interviews by a high-level manager we will call Sandra whose early interaction with an employee, Terrence, revealed his dissatisfaction with his administratively oriented job as director of training. His disappointment was accentuated by Sandra being hired from the outside to fill the new position above him, which he interpreted as he being stalled in place instead of advancing to the next level. Sandra met weekly with Terrence and developed understanding of his interests and abilities, which included the clinical training and preparation he had completed and worked in before being promoted into his current job. Sandra asked Terrence what he needed and how he would like Sandra’s help in reaching his goals.

As Sandra gained more perspective and awareness of the dynamics that supported growth and success in the new organization she was working in, she shared her observations with Terrence to get his honest impressions and build a collaborative relationship focused on his progress toward what he wanted. Sandra believed that Terence’s current administrative position would not lead him to the greater responsibility he wanted for working directly with the organization’s clients, so she recommended that he pursue a more clinically focused position that was opening up.

Terrence expressed doubts and fears about Sandra’s suggestion because he viewed the alternative position as a step down, and away from the expanded level of responsibility he sought. Sandra, his manager, reassured him that she would support him through the transition and advocate for his continued growth and advancement. With this assurance from Sandra and Terrence’s growing trust in her genuine commitment to helping him achieve his goals, he made the move. As Sandra had promised, she helped Terrence by approving his enrollment in more training in the clinical leadership skills he yearned to develop and apply.

Before long, with Sandra’s help and support, Terrence was ready and positioned to advance into a higher-level clinical role that he had dreamed of. By this time, the two had developed a mutually trusting and supportive working relationship. Terrence admitted to Sandra that he had initially felt fear and a lack of trust when she arrived at the organization as his new boss. Now he trusted Sandra and thanked her for helping him to succeed.

Sandra’s pleasure with Terrence’s success and the transformation of their relationship was apparent as she shared this success story. Having experienced first-hand the benefits of supportive coaching from his own manager, Terrence in turn was following Sandra’s example to actively develop his own team members. He was involving them in more decision making about their development and their contributions to the organization’s mission serving its clients and promoting sound financial health for the organization.

Performance Tracking and Planning

Since health care attracts people who want to help others lead healthier lives, who embrace challenges in difficult subject matter and handling life-or-death responsibilities, and who take pride in doing things well to earn the credentials required in their professions, well-designed coaching can be immensely valuable. By allocating time consistently to do coaching regularly with all the employees who report to you directly, you foster their growth and development and you will prevent many performance problems. This makes annual performance reviews, in accordance with the requirements of your organization, much more positive experiences for you and the people who report to you.

Ongoing Conversations on Progress and Performance

You should be reviewing regularly with your employees their goals and progress in meeting them along with their ongoing performance in meeting requirements such as productivity standards or targeted treatment outcome measures. This is part of your ongoing coaching and development meetings, with at least monthly frequency.

Keep Track of Accomplishments and Deficiencies

You should also document performance deficiencies as well as accomplishments, for follow-up development and to build the content for annual reviews. Having a record of accomplishments may help you reward your employees who have performed well. If your organization requires ratings of performance during an annual review, there should be no surprises to any employee who receives low ratings from you. Because you have been having conversations all along the way about your expectations along with your feedback on the employee’s performance and any concerns you have, the employee would be aware of any problems he needs to correct and would have the opportunity to work with you on that before they become more serious.

Reaching for the Future

Just as you discussed with your employees the performance expectations of their current positions and help them assess and measure their progress and success relative to those requirements, you can have similar conversations about their goals for the future and what they need to work on to move toward them. At the Mental Health Center of Denver, we used the Catalytic Coaching approach, developed by Garold Markle (2000).45 We asked employees what they wanted to accomplish and what they aspired to do, which often revealed dreams and professional goals we could help them attain. That’s how a number of people moved into their first positions as managers, sometimes outside their current departments, and with the support and encouragement of the managers they reported to!

Performance Problems: What To Do?

Now suppose that you have established a rhythm for working with your employees. You have gotten into the habit of providing timely feedback, set up meetings with them to provide further feedback and coaching, and you have made work assignments and delegated some tasks from your set of work to theirs. You have asked questions, been clear in setting direction, and clearly defined—via “word pictures” you have constructed with your employees’ participation—what good performance looks like and when things are due. Congratulations on setting the stage so everything goes smoothly and each of your employees performs at high levels that meet and exceed your expectations!

But what if everything does not go as you expect? Suppose you see problems, communicate your concerns to an employee, and agree to what needs to change, but the problem persists and there is no improvement? It is a good idea to consult with your human resources department and review the laws in your state and rules in your organization. For the most part in the United States, employment is at will, which means an employee can be fired at any time for a good reason, a bad reason, or no reason, provided the reason is not illegal.46 This means that you can terminate a person’s employment and you do not necessarily need a performance-related reason, but you cannot terminate someone for an illegal reason, such as discriminating against employees based on their membership in groups related to race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age, disability, or genetic information.47

So, even if, technically, an employer does have the right to terminate employees, employees may (and often do) file lawsuits against employers, often with the claim that the unwarranted action was based on illegal discrimination against the employee. And if your employees belong to a labor union, there may be specific actions spelled out in the labor agreement contract.

Start with a Conversation

According to Jeff Tucker, JD, VP of Human Resources at the Mental Health Center of Denver, when you have concerns about the performance or problem behaviors of any of your employees, first talk to that person, and then you must document your conversation. This is important in case the problem persists and you need to take further steps. Be sure that an outside observer would be able to understand what had transpired between the supervisor and employee. Later, if you decide to take disciplinary action that could lead to terminating the employee, you need solid evidence that you talked to the employee about the specific issue(s) that led to your action.

Follow Up in Writing

Jeff recommends a written follow-up message, usually in an e-mail if that is what your organization uses to communicate in writing, that documents the conversation and clarifies the intent. He recommends you frame it as a description of your conversation rather than in detached third-person language.48 At this stage, you are just acknowledging what you noticed and documenting your conversation in writing so the employee understands that you view it as important. For example, to document an initial conversation before it becomes more structured disciplinary action, it is better to write your message in terms of “You and I talked about . . .” rather than sending the employee a notice written in formal third-person language such as: “Medical Director Morgan Miranda spoke with Doctor Ryan Milton about Doctor Milton’s practice of . . .”

Suppose, for example, you have an employee who tried to schedule paid time off for a last-minute vacation, and your other team members complained to you after the employee asked them to cover for her. So, you have a conversation with the employee to make sure she understands the required lead time and how coverage is arranged for such requests, and then you send her an e-mail. To clarify your intent to address concerns about paid time off, you could start by writing,

“Ryan, I get a lot of questions about paid time off and how it works.” Then, you continue with what you discussed. “As we talked about today, our team follows the practice of planning ahead of time for vacation requests. Requests should be submitted at least two weeks ahead of time to Eli, who handles our schedule changes and balances requests for coverage so they are distributed fairly. I’m glad we discussed this today to make sure you understand the process and how it supports smooth coverage for our team members and patients. Thank you for your cooperation. Sincerely, Morgan.”

The Specific Problematic Behavior

This shows that you did communicate your policy and what you expect the employee to do. It leaves the employee with a clear reference to be prepared to handle the issue correctly in the future and provides you with solid documentation in case you need to refer to it for future follow-up if the same problem persists.

Keep in mind Jeff’s advice to clearly show that you talked to the employee about the specific issue that was problematic. For example, it is not a good idea for you to suddenly fire an employee for being late to work if you never communicated your concern specifically about the lateness in arriving at work. It is not close enough if you did warn the person only that there would be consequences if she continued to be late in her documentation of treatment and services, and then she shows up late one day, so you fire her for being tardy because you feel like you have had enough of her bad behavior.

Plan for Improvements and Its Measurements

Or you might have an employee with poor performance not related to policy violations or undesirable habits, but he is not producing at the expected levels of proficiency or results. Start with the same approach, have a conversation. Compare his actual performance with the expected level, using objective data if available, such as reports of productivity, patient satisfaction, timeliness of documentation, scores on quality reviews. Ask for his commitment to improve and his ideas on how he will do it. Develop a plan with him with timelines and dates for when he will complete the needed changes and how results will be measured. Now you have your objective guidelines to encourage progress and monitor it.

Evaluate Progress

As you review your employee’s progress with him, you as the manager have the responsibility to determine whether satisfactory progress is being made and to communicate your assessment to him so he knows where he stands. At this point, you have communicated your concerns to your employee so he is aware of the problem and has reasonable opportunity to correct problems you have now made him aware of. And you have established the basis for continuing to develop a formal written warning and a corrective action plan if he does not improve as required.

Progressive Discipline

If you determine that the problem persists and will require further action, you are moving toward what is known as progressive discipline, in which increasingly serious consequences may be warranted. According to Mader-Clark and Guerin (2016), “Most large companies use some form of progressive discipline . . . . Whether they are called positive discipline programs, performance improvement plans, corrective action procedures, or something else, these systems are similar at their core, . . . based on the same principles: that the company’s disciplinary response should be appropriate and proportionate to the employee’s conduct.”49 You need to work with your human resources department to follow their guidelines and organizational requirements for determining consequences, such as putting the employee on probationary status or suspending some privileges, and timelines which may be leading to termination if improvement goals are not met.

Immediate Action to Suspend or Terminate an Employee

Because of the serious responsibilities in health care to protect patients from harm and potential life-and-death consequences, some employee actions could be serious enough that you will need to bypass the initial conversation and progressive discipline to proceed to immediate action to remove an employee from the workplace. This may be necessary to protect the organization, patients, other employees, or the public from harm. Such employee actions could involve illegal and unsafe practices such as substandard care practices that put patients in danger of serious health consequences, illegal dispensing of drugs, theft or improper handling of controlled substances, harassment and other misconduct toward patients or other staff, fraudulent activities, and others as specifically identified in your organization’s policies or employee handbook.

Serious misconduct could warrant immediate termination of the employee or suspension from work, with or without pay depending on the alleged actions, while an investigation is conducted. You might need to notify licensing boards for violations of professional ethics or practice standards, or even law enforcement for illegal activities or threats to safety. It is essential that you involve your human resources department. They have expertise in the specific steps to follow to investigate possible misconduct, and they know who else to contact such as your organization’s insurance carriers for malpractice and other liability.

Remember that while performance problems can be challenging, now that you know about the processes for handling them, you can be more confident and feel prepared and professional if the time comes when you do need to address them. You will not be dealing with them alone if they turn serious. Stay in close touch with your human resources department and your boss for guidance and support.

My colleague, Roy Starks, MA, VP of Rehabilitation Services and Reaching Recovery at the Mental Health Center of Denver, successfully motivated his teams to achieve high levels of performance by focusing them on meaningful outcomes for the consumers they worked with. Nevertheless, in his long career as a manager, he recognized that despite what you do as a manager, some people do not perform as well as needed. His advice to new managers is, “Don’t take it personally.”50

When Dixie Casford remarked, “Terminations should never be easy,” she recognized that they might be necessary but should not be something we enjoy.51 It is easier to set expectations ahead of time. Another manager, who needed to develop a corrective action plan with an employee who was making insufficient progress, reported that the specificity of plans and goals with monitoring was helpful. After working together through the process, the employee told this manager he was her strongest ally.

Chapter Summary and Key Points

In this chapter, we looked at what health care managers do, showed you how to delegate, and looked at the power you have and trust you need to build in your new managerial role. We drew upon some resources such as books that help managers in any industry handle their new leadership responsibilities, and showed you some representative scenarios that illustrate what you can expect in a health care setting. We emphasized the importance of setting clear expectations for behavior and performance, showed you how to hold people accountable, and looked at how to coach your employees for their performance and development. We considered performance problems and advised you on how to handle them. Now you are in charge and ready to manage your team successfully!

Key Points: