Managing Up, Down, and All Around!

Chapter Overview

Being a manager involves supervising and leading the team of people who report to you, and communicating clearly what you expect them to do. In Chapter 2 we looked at how you take charge and get started in that part of your role, and continued in Chapter 3 with structured techniques to help you plan and organize. Now, let us consider other important people in your new world of management.

It is vitally important that you build a positive relationship with your boss and ensure you are meeting your boss’s needs and expectations of you. Those you work with as colleagues and peers also are important in your work world. We explore ways for you to build and sustain important relationships in multiple directions. You will gain wider perspective and effectiveness as you practice managing up, down, and all around! These are essential skills as you make the transition from providing direct patient care to managing the people and other resources involved in health care administration.

Topics in this chapter:

- Your new world and who is in it

- Managing up: your important relationship with your boss

- The importance of influence

- Building positive relationships

- Up, down, and all around your successful transition to administration

- Chapter summary and key points

- Learning activities for this chapter

Your New World and Who Is in It

Your role has changed relative to those around you, and this changes your relationships. In Chapter 2, we considered new dynamics that emerge when you move to a position of responsibility for a team or group of your former teammates and peers. Or perhaps you were hired into the organization to manage people who were already working there. In any case, your new role as manager requires you to take charge, acknowledge additional power and authority you now hold, set expectations for your team and meet the expectations for your performance. You are learning to lead by understanding the values of those who now report to you and leveraging areas of alignment.

Now, let us broaden your scope. Who else do you need to consider as part of your new world? Current articles refer to the need to manage up, down, and sideways. Thomas Barta and Patrick Barwise (2017) found evidence that managing upward and horizontally can improve your business impact and career success. They specifically mention the importance of your bosses and forging strong ties with your colleagues to build momentum.1 And what about important other people? They can include peers, customers, outside regulators with authority over your organization, patients, and their families. Strayer (2017) includes “managing outward,” where, “Relationship building and active communication are essential, especially when timelines are tight, whether your customer (who receives your output) is external or internal to your company.”2

The Value of Relationships Up, Down, and All Around

Consider what relationships you have or need to build. As you work through this chapter, consider what is expected between you and others in these relationships, and how to foster collaboration with others from the perspective of your new role as manager, leader, or administrator.

For Erica Snow, MS, MPA, the relationships she built helped her succeed in her role as a quality improvement coordinator and then as she advanced to manager. She worked internally to enlist the support of clinical managers to promote the use of quality improvement methods with their teams. Her external relationships, along with her growing content knowledge of health care operations and funding, led to new career opportunities with increased responsibilities. She was recruited to join a health care funding foundation through her professional network, which she had expanded by participating in several leadership fellowships, which are particularly helpful in building a broader base of professional relationships. When I interviewed her for this book, she reminded me that as her boss at the time, I had written a recommendation for her for one of these fellowships.3

I remember how I had enjoyed working with Erica and appreciated her valuable contributions to our team and organization. This made it easy for me to support her in activities to help her advance her career and contribute to broad goals for health care access throughout our community. Now let’s explore more about your relationship with your boss and how managing upward can enhance your success.

Managing Up: Your Important Relationship with Your Boss

Your boss is a particularly important person in your work life because this is the person who can help you learn and develop your capabilities, facilitate your access to helpful resources and opportunities, advocate for you and your advancement, deliver rewards for your good performance, and determine consequences if you do not deliver what is needed or desired. So, let’s start with this important relationship.

Dobson and Dobson (2000) explain, “We can’t accomplish our work and our objectives without the willing and voluntary cooperation of numerous people over whom we have no direct control.”4 You need to build a relationship with your boss which results in mutual success that includes being listened to, having your ideas respected, getting timely decisions from your boss, and building your influence to help you get your job and goals accomplished.5

Getting Clear: Who Do You Report to?

We have seen examples of complexity in health care organizations and evolving rules about leadership and responsibility for the activities of others. So, it is important to clarify who your boss is. Who do you report to? For consistency, we will refer to this person as your boss, although the actual title is something else such as Team Leader, Supervisor, Manager, Director, Associate Administrator, or perhaps even Vice President or Chief. This is most likely the person who had the final say in choosing you for your position, although the Human Resources department was likely involved in discussions about salary, benefits, and other administrative aspects of your position, and other team members may have participated in your interviews when you applied for your new position.

Your boss is usually the person who approves of your administrative activities such as work time scheduling, time off, time reporting for payroll, expense reports, and other expenditures, depending on your level of budgetary authority. This is also the person who holds you accountable for achieving the goals and results expected of you in your new managerial position and offers praise and formal rewards or delivers corrective feedback and disciplinary actions related to your performance.

How You Support and Value Your Boss

Dobson and Dobson (2000) suggest that you develop a productive and mutually beneficial experience for you and your boss by providing support and showing that you value him. “When you feel that you are supported and valued, it’s easier to take—and even welcome—feedback and suggestions for change and growth. Demonstrate the same behavior upward that you appreciate and value downward.” Managing up is not about manipulating your boss. No one likes to feel manipulated or used by others to get their way. Rather, it should involve helping your boss to be effective and productive by supporting him to help him stay organized or fill in areas of weaknesses, looking out for his needs, and providing truthful feedback when needed.6

Keep in mind that you and your performance reflect on your boss and her capabilities. As Shari Harley (2013) reminds us, “Your job is to make your boss look good.”7 Your boss has a boss, too, and other customers and stakeholders judge the results and effectiveness of activities in your boss’s area of responsibility. As a new manager, your work should demonstrate that your boss made the right decision in choosing you.

Loyalty and Respecting the Chain of Command

Dobson and Dobson explain the importance of loyalty to your boss, and the need for you to manage this key relationship. In particular, you need to understand and respect the chain of command. As Dobson and Dobson (2000) explain, “Violating the chain of command means to bypass one or more intermediate levels of supervision to get job assignments or decisions from a higher level. Although it may be tempting as a short-run strategy, especially if you’re not getting the support you need or want from your immediate boss, this behavior has several drawbacks: confusion, bad decisions, or mistakes. Each level of the chain has information and goals. Bypassing the chain cuts that information out of the process.” It is like playing off parents against one another to get the decision the child wants. It shows lack of loyalty to your boss, and lack of understanding about organizational structure, both of which can raise the concerns of others about you for doing it.8

Relationships you may have developed with those above your boss are fine for special projects and assignments, mentoring, and networking as long as your boss was properly informed and consulted. Do not collude with others who go around your boss. Do not deliberately keep your boss out of the loop; it is your responsibility to direct decisions and information back to your boss. Dobson and Dobson (2000) warn, “Don’t use these relationships to reverse your boss’s decisions, get job assignments without your boss’s approval, or keep your boss in the dark about those relationships . . . . Note that if your boss feels bypassed by his or her own boss, feelings of paranoia and persecution may result . . . so you may bear the brunt of your boss’s resentment.”9

Detect and Avoid Loyalty Problems

Occasional emergency or crisis situations may require bypassing normal channels of communication, agreement, or approvals when there is urgency needed to prevent serious consequences. However, most normal activities and decisions are handled more appropriately by respecting appropriate channels of communication and decision making; otherwise, confusion and weakened trust become unwelcome characteristics of the workplace and can detract from safe and coordinated care for patients.

Keep Your Boss in the Loop on the Things She Needs and Wants to Know About

These include things that require her support or approval, such as incurring significant expenses, or significant deviations from regular policies. Find out when you start in your position what the procedures are for spending money, and your level of budgetary and sign-off authority. This can vary with the organization—in some, a supervisor has visibility and access to a team budget and has the authority to make or approve expenses for the team he leads. In others, directors do not have direct access to a budget that rolls up to a vice president, so even a director must ask the person she reports to for support and approval of expenditures.

Keep in mind that even if you develop good relationships with senior leaders above your boss and their level of approval is necessary to sign off on something, you need to make sure your boss knows what you are requesting and supports the project. Most bosses do not like surprises about major things happening in their areas of responsibility that they were not aware of! Nor are they happy about having to support a decision made by someone else who did not have all the facts or expertise needed to ensure that things work as intended. Remember, part of your job is to help your boss succeed. Your boss influences many factors that can make your working life better or worse. It is in your best interest to support rather than alienate this person.

Keep Your Boss Informed

Let him know about the activities and progress of you and the teams that you manage, especially when they are nonroutine, have the potential for particularly high impact, or something is going wrong. This helps your boss manage resources effectively, ensure alignment of activities to support the organization’s goals, provide guidance when needed, support your efforts, warn the senior managers above him, and communicate with other internal and external stakeholders who may be influenced by your team’s activities.

When things are going well, this is your chance to shine by communicating your team’s successes and recognizing your team members for their good work and contributions. When there are problems, involving your boss appropriately can help you turn things around effectively, minimize damaging outcomes, and can even deepen your boss’s respect for you and earn you the reputation as an effective problem-solver who takes responsibility and does not avoid the difficult issues.

Find Out by Asking What Level of Involvement Your Boss Wants

Some bosses like to be included in your communications, such as being copied on e-mails for their information, especially when you are new and getting started in your position. Others prefer that you just handle the routine details of what you are doing unless there are special circumstances. When you are new or in doubt, it is better to overcommunicate until you are confident that you have hit the right level of what works for your boss.

Include him a few times and check in to ask whether he wants to know about such issues or not. You might simply say, “I copied you on my message on pharmacy planning in case you’re interested in my team’s interactions with others. How much information would you like to receive about communications like that when they’re in the initial stages? Do you want to see these messages or just hear about results or problems if they arise?”

Aligning with Your Boss’s Goals and Needs

As Dobson and Dobson (2000) point out, “Doing the right thing and doing things right aren’t just measured by you. Your boss legitimately has a lot of input in deciding what ‘right’ means.” Those authors further explain that the importance attributed to work activities is a “negotiated product” consisting of the perceptions of your boss and senior managers above your boss, your coworkers, and your customers.10 “Doing good work means not only delivering quality performance, but sometimes more important, knowing what quality performance is.” A good place to start is to review your job description, make sure you understand performance standards and how you will be measured in your work toward them, determine how to allocate your time and effort, and ask for feedback to ensure your plans are in alignment with what your boss thinks is important.11

What is the best way to ensure that you are meeting the needs and expectations of your boss and others? First you need to understand clearly what those expectations are, and the best way is to ask directly. Shari Harley (2013) emphasizes why this is so important: “Ask how you’re being evaluated. If you don’t know how your performance is being measured and what a good job looks like, you might meet your manager’s expectations and, then again, you might not.”12

Health care settings are very complex, filled with standards and requirements that may seem to conflict and compete, and where interpretation of priorities can seem ambiguous. It is essential that your activities align with the expectations of your boss to support the goals of your organization. Do not assume and leave this to chance! As Harley further explains, “When organizations are aligned, your annual goals are ultimately a portion of your manager’s goals . . . . What you think is important may not be what your manager thinks is important. Work on agreed-upon priorities to avoid major frustration later.”13

Checklist to Ensure Alignment

When you begin in your new position, or are assigned to a new boss, gather these items and review them with her to ensure that you are in alignment in your expectations of your responsibilities, activities, and performance.

- Your job description. Pay particular attention to duties and responsibilities and make sure you agree that the list of major activities is complete and descriptions are accurate.

- The performance review form and criteria used in your organization. Verify with your boss that this, or another format, is what she plans to use. Make sure you are aware of how your performance will be reviewed, the expected standards, and rating criteria for your performance.

- Other performance standards for the organization and your team that you are expected to manage and deliver. These might be part of strategic and operational plans established at the organizational level or by specific departments.

- Time-limited projects and their goals that you are responsible for meeting.

- A list of other things you are working on that are not included elsewhere and contribute to the success of your team, department, goals of your boss, and the overall organization.

Organize Your Activities to Review and Track Progress

In the previous chapter, we examined the value of making plans and setting goals. We considered why it is important to write your goals down and communicate them with your boss. Let’s take a closer look now at how you could structure and present your activities in a way that shows what you are focusing on and your performance in achieving what you believe is expected of you. This demonstrates that you are goal-oriented, accountable, and respectful of your boss’s time because you took the time and initiative to organize the information succinctly before meeting with him.

Create a table to keep track of the key things you need to review with your boss, at least initially, to ensure your priorities for your activities and efforts are aligned with his. Presenting specific information in a format that is clear and easy to comprehend sets the stage for managing expectations by clarifying exactly what levels of performance are expected and being achieved by you. This helps with evaluating progress and recalibrating objectives or target levels of performance if needed. We explained such actions through the Expectation Management Model, introduced in Chapter 2 to set and manage expectations, and applied in Chapter 3 to follow up on decisions, commitments, and negotiations about expectations.

Here is an example of a format you can use or adapt to the needs of your particular organization and responsibilities (Table 4.1).

Gauge the Amount of Detail Needed

Be alert to your boss’s preferences for high-level vision versus details. Start with the smallest number of activities that covers the important priorities and columns needed to keep track of them. Follow your boss’s lead in adding additional information she asks about, or eliminating what she finds extraneous or irrelevant. Retain what you need for your own effective tracking to make sure you are meeting the expectations of your boss and other people or functions you are accountable to, and streamline if needed for productive conversations with your boss.

Watch for nonverbal cues, such as your boss looking overwhelmed, distracted, or uninterested, but do not make assumptions. To verify that you are on target, ask if the format and information you are providing is helpful and whether your boss prefers a different way of organizing it. Asking for and utilizing feedback is essential to your success, and you need to gain comfort and proficiency in having such dialogues not only with your boss but also with other people who work with you. After all, how can you correct problems or improve needed skills that you are not even aware of the need to address? In Volume II, Chapter 2, we offer some specific ways for you to request and receive feedback.

Review and Negotiate

Having something written down for you to review together can help you and your boss ensure you are both aligned in your focus and expectations. Notice Table 4.1, the example table of activities, includes some projects and activities that are not in the job description. Including them helps keep your boss aware of ad hoc assignments you may have been given or volunteered to handle that are not part of your official job description and were not assigned by your boss but require your time and commitment to complete to meet someone else’s expectations.

You may need to negotiate with your boss some trade-offs to add or delete some responsibilities to best align with her expectations for what you deliver. You may discover together some opportunities to delegate some of your responsibilities down to your team members or sideways to other colleagues. The guidelines for delegating that we covered in Chapter 2 can be applied in delegating to others who do not report to you to make sure there is clear agreement about what you are requesting and what they are accepting and agreeing to deliver. And, when they do not report to you, you need to rely even more on your ability to influence others to accept assignments or fulfill commitments in the spirit of working collaboratively with you to achieve organizational goals together.

The Importance of Influence

You need to influence, rather than force, others to want to work collaboratively with you. In the words of Dale Carnegie, “The only way on earth to influence other people is to talk about what they want and show them how to get it.”14 Although it was written initially in 1936, Carnegie’s book, How to Win Friends and Influence People, remains so popular that it was one of 10 books listed in a reader poll for a book published in 2009 on the 100 best business books of all time.15 As Carnegie points out, each of us is interested in what we want.

Most of the time, managers really cannot make anyone else do anything unless the person wants to do it because it fills his needs or she is motivated for her own reasons. When people report to us, they are likely to do what we request of them if they need their jobs or are motivated to continue being employed in our organization or led by us. Jackie Attlesey-Pries, Chief Nursing Officer at Boulder Community Health, explained that when people do not report to you, rather than exerting control over them, you need to inspire people to direct the work.16

Leadership Helps You Manage Effectively

Clearly, the complex world of health care requires managing many different activities and work done by other people along with the things you still do directly yourself. Armstrong (2013) describes management and compares it to leadership. Management, he explains, is about obtaining and applying resources, including people, money, facilities, equipment, information and knowledge. Leadership focuses on people. “It is not enough to be a good manager of resources, you also have to be a good leader of people . . . . To lead people is to inspire, influence and guide. Leadership involves developing and communicating a vision for the future, motivating people and securing their engagement. It is an influencing process aimed at goal achievement.”17

Several people mentioned in their interviews the role of confidence and trust in your development as a leader. As Chris Noonan, CEO Group Chairman at Vistage International, says, “Show up as a leader and people will follow.”18 Mary Peelen, Director of Health Information Systems Management at the Mental Health Center of Denver adds, “If your leader talks about things and you trust her, you follow.”19

Leadership skills also help you when you are in situations as a manager or administrator where you do not have direct supervisory responsibility over other people working with you. These could include organizational activities or projects where you are accountable for the results in important aspects of health care such as service quality, treatment outcomes, compliance, record-keeping, or patient satisfaction, which involve multiple teams and departments with people who do not report to you. Since you do not have direct authority over these people, you need to become effective in influencing them and collaborating with people coming from different clinical disciplines and areas of responsibility.

What about other people who work with you, when you have no official authority over them to require them to cooperate with you? This is the key to managing all around, where you rely on your relationships and influence with other people who do not report to you. The following examples from interview participants show how they lead effectively with influence.

Leading with Influence Instead of a Title

When Trista Ross, PharmD, was an intern, she needed to complete an internship project, which was to improve customer satisfaction. This required “leading without a title.” She didn’t have positional authority to require people to support and participate in her project. Instead, she engaged people to really rally around it. She made candy bags with survey reminders and gave them to pharmacy customers as they picked up their prescriptions.

The pharmacy manager participated in distributing the bags and surveys, and it caught on through his leading by example. The project was very successful with all the support Trista enlisted from people who worked in the pharmacy and did not report to her but wanted to help. Satisfaction scores went up because there were more positive responses, not just from the unhappy customers who sought to complain via the satisfaction survey. Feedback was actionable; for example, a customer complained about long wait times, which the team addressed.20 Thus, even though as an intern she did not have official control over others, she was able to inspire positive change in the organization.

From Command-and-Control to Matrixed Management

Preston Simmons, DSc, MHA, FACHE, described the shift from command-and-control approaches that were taught in earlier medical education toward a more “matrixed environment,” which refers to people following leadership and direction from people who do not have direct authority over them but still are responsible for the results of teams that work together to accomplish their shared goals. When leading in these current structures, it is important to work with and through others.21 This means influencing, guiding, and empowering others rather than directly telling them what to do.

Several doctors elaborated on these approaches. Michael Sullivan, MD, observes, “A leader is a change agent. The challenge is in getting people to believe and own the change; otherwise, they might comply but the change isn’t sustainable. When physicians take charge and tell people what to do that isn’t being a change-leader.” He explained the need for humility and insight to work with staff from other professional disciplines. “The most successful understand that the power doesn’t come from the degree.”22

Collaborative Communication to Influence and Engage Participation

Recognize and value others; you need them to work with you to support your goals and collaborate with you to achieve shared visions and goals. Michael Ward, MD, PhD, strives for open communication in the clinical teams he leads to ensure that everyone’s input and concerns are heard. He values feedback from all members of the team and actively encourages members of his team in other clinical disciplines to bring forth their perspectives, especially if they notice something that could get in the way of safe and effective treatment for the patients the team treats.23

Ken Bellian, MD, MBA, recommends engaging others through communication that recognizes their roles and how they contribute to organizational success. For example, translate the organization’s strategic plan up and down so everyone understands his and her role. You could talk with the person who cleans facilities about his role in patient experience, patient safety, and quality metrics. Then he would understand the importance and value of his contributions in preventing surgical site infections in patients.24

Enlisting Support through Engagement and Participation

A number of people interviewed are very effective in enlisting the support of others in the organization who do not report to them. Their success depends on their ability to engage others in supporting their goals, as summarized in Table 4.2.

Building Positive Relationships

Kathleen Winsor-Games (2018) explains that in the context of your professional success factors, “Your relationships depend on your ability to influence and collaborate with others. Earn trust by communicating transparently and honoring commitments. Cultivate active listening skills. Too few of us feel truly heard in our daily lives. This means interrupting less often and hearing the other person out, rather than planning what to say next.”28 As illustrated in the previous section, you can develop your influence without imposing directive control on the people you need to lead. When people feel that you respect them, value them, listen to them, and you show that you care about their ideas, they are more likely to cooperate with you and support you, whether or not you have any direct control over them.

Your success depends on the cooperation of others to get things done. You cannot do it all alone. Sometimes you need resources and information that you do not have and need to get from others, and sometimes it is the other way around. It is easier to ask for what you need from someone whom you have already built a relationship with by getting to know them and helping them by providing what they need.

How to Build Your Business Relationships

Shari Harley (2013) offers straightforward advice about this. “If you want to take charge of your career, invest time in your business relationships. Ask questions about what people need, want, and are expecting from you.”29 As we discussed in Chapter 3, this is an important part of your plan for your first 30/60/90 days in your new role; you should make a point of building these relationships within your first 30 days. My 30/60/90-day plan focused heavily on meeting others and asking about their needs. This established positive working relationships that were extremely helpful and valuable in my ongoing work throughout the organization.

Focusing on others and asking about their needs is a good way to start building relationships. One way to start is to seek out new colleagues, introduce yourself and your new role, and invest some time in getting to know them, asking them questions, and sharing some information about yourself.

Suggested Avenues to Initiate Work Relationships

- Invite coworkers to coffee or lunch for casual conversation and to get to know each other. This is an opportunity to share information about each of your backgrounds and work goals to discover ways to align and support each other at work. And as you begin to share some information about your personal life and interests, you will start to connect on a friendly interpersonal basis. Perhaps you will discover some shared experiences or interests outside of work that you can enjoy talking about together such as regions you have lived in, activities you enjoy, sports and activities of family members, books, movies and other media and entertainment, hobbies, places you like to go to, and other forms of recreation.

- Allocate some time for lunch or brief breaks in common areas where others congregate. Initiate conversations with others, ask questions about them, their work, and other interests. It is easy to start with casual comments that others can agree to, such as, “It’s nice to find fresh, hot coffee on a cold day!” Then move to a brief introduction, “Hi, I’m Taylor Gray. What’s your name?” and progress to asking about where they work and what they do in the organization before you offer information about yourself. Then you could comment or ask a question about what they’re working on: “It’s great to meet someone in Information Services! What’s it been like for you to support the new health record system conversion?” Now you may have the start of a relationship in another department that you can continue to build on.

- Join work groups and committees that include people from outside your own team and department. To direct your time wisely, select those where you have a genuine interest and can learn or contribute your experience and skills in useful ways.

- Join company-sponsored teams or recreational activities. Use recreational facilities where you will encounter people from other areas. Learn their names and roles and build up conversations and interaction with them.

- Volunteer to handle activities that require your special expertise and offer your help to people who work in other departments and levels. For example, you might offer to conduct training in areas of needed skill development for others, write and edit articles for company newsletters, or organize visible events and campaigns for your organization.

- Represent your team or organization in external activities to build relationships in your local and professional community.

Building and Deepening Relationships

As people get to know you, they become more interested in spending time with you and helping you access resources to meet your goals. And it is important to follow through and deliver what you commit to do, as we explained in the previous chapter. When you deliver to others what they need and expect from you, that establishes their trust in you and their willingness to provide what you need from them. People learn that they can count on you to support them and deliver what you promise, and they become willing to support you when you need it.

Often, what people need from you is information and cooperation that helps them accomplish goals and fulfill their commitments. As we and our colleagues build collaboration and cooperation across our teams and functional areas of responsibility, we contribute to the success of the overall organization.

Nurture Relationships with Gratitude

You also need to nurture your associations with others to obtain their support. Gratitude and willingness to reciprocate are important. Cherie Sohnen-Moe (2016) reminds us, “One of the most essential habits to develop is prompt and gracious acknowledgment of all the people who support you. A little recognition goes a long way!”30 Matthew Kelly (2007) refers to appreciation as “the strongest currency in the corporate culture . . . . Nobody likes to feel that they are being taken for granted—that just builds resentment.”31

Examples of Actions and Conversations That Build Relationships

- Recognize others by asking for their help or advice. “I heard you’ve been successful at getting different people to work smoothly together. I’m starting a new project where people seem to have very different goals. Do you have any suggestions for leading them toward closer alignment?”

- Offer your help to others. “I heard you say you’d be away next month when you’re scheduled to teach a CPR class. I’m certified to do that, so if you need someone to cover it for you, I’d be happy to do it.” Even if your colleague has it covered, she’ll likely appreciate your offer and might seek you out next time.

- Compliment someone on her accomplishment or performance. “I really enjoyed your presentation today. I learned a lot from all your research and experience with trauma-informed care! Thank you for sharing it with us, it will really help us provide better treatment to our patients.” Of course, with any compliment, make sure it is sincere and be specific enough that people understand what you are recognizing them for.

- Show appreciation by thanking someone, sincerely and specifically. “Thank you for supporting me in today’s meeting. Your speaking up helped others understand why I believe this issue is so important. I really appreciate your help.”

- Invite someone to join your committee or participate in a work group. “I’ve been assigned to lead the critical incident committee. I’d really value your objective perspective on difficult problems; would you be willing to serve on this committee with me?”

- Offer to share resources and information. “I have a copy of that book you wanted to look at. Would you like to borrow it?” “It sounds like there was some confusion about how the committee reached its decision last week. I was in the meeting where the data was presented. Would you like to see a copy of it?” Of course, you will protect sensitive information and share only what you are authorized to disclose.

Benefits of Relationships around the Organization

There are many good reasons for developing relationships with others in your organization. It is good to build give-and-take collaboration so you can get and offer help to others when needed. Do not be overly dependent on your boss. It is not necessary for you to direct every question to your boss when there are peers and others who can help you. Your other relationships can increase your value in helping your team when you learn about other resources and activities elsewhere in the organization. This can be true of other community activities you participate in outside your own organization.

For example, when I was volunteering with another local agency, I found out that agency was moving part of its operations to a new facility. I shared this nonconfidential but “insider” information with my boss promptly, who quickly approached his community collaborators to secure the soon-to-be-vacated space for our program. This helped our team expand our reach to serve more people, which made my boss and his boss very happy.

Other opportunities may come up that position you to work with and get to know others in the organization. I remember when I was a new therapist and our team was allocated two slots to attend the annual statewide mental health conference. I expected to defer to the more senior members on my team, but to my surprise, no one else wanted to take week-end time to attend the conference, so I gratefully accepted the opportunity to not only learn new skills, but to get to know other people in my organization. I attended an event organized by our CEO to gather members of our organization, and there I met our medical director for the first time. He turned out to be the hiring manager several months later of the next position I interviewed for and was selected to fill.

I did not normally have day-to-day contact with the medical director, but I had another opportunity to work with him in a training exercise dyad in a seminar I was allowed to attend because I had completed my regular work with clients and was caught up on my documentation and record-keeping. Having met and established some dialogue with him beforehand made me much more comfortable and confident in explaining in my interview how I could contribute in the new role I was applying for and filled.

Another opportunity arose when our CEO actively sought participation from staff at different levels to help improve organizational morale. I had not had the opportunity to interact with him directly before that point but when he put out an open invitation in our companywide newsletter for interested people to join his morale committee, I ran it by my supervisor. She respected my work and supported my professional growth and interests, so with her support, I joined the committee and established positive working relationships with not only the CEO but with several others who would become valuable collaborators and teammates in my next position in administration.

Besides making your work time more pleasant and enjoyable, there are many benefits in cultivating working relationships all around your organization or community. Your boss might move to other responsibilities or out of the organization altogether and you might find yourself moved to another team or role and reporting to someone else. Make sure you and your work are known and viewed favorably by others who can support your efforts and advocate for you when situations change (as they inevitably will in the fast-paced world of health care delivery!) This is one of the reasons it is important for you to develop a solid positive reputation for aligning with organizational values, making valuable contributions toward the organization’s goals, and providing good customer service to other teams.

Up, Down, and All Around for Your Successful Transition to Administration

In this chapter, we have focused a lot on relationships, which are at the core of most of the skills we have covered in this first volume, Management Skills for Clinicians, Volume I: Making the Transition from Patient Care to Health Care Administration. Your world has expanded from a focus on individual patients you have cared for to working within a system of care where you manage people and administer resources to serve your organization’s populations of patients. The chapters in this first volume helped you understand the special features of managing in health care settings, take charge to lead your team, manage the performance of those who report to you, involve others in planning, organize your activities, influence others around you to collaborate with you, and build relationships with the people you manage, along with your boss and others around you. Now you are prepared to manage in all directions to lead other professionals and administer many of the necessary activities that keep health care organizations running smoothly.

As you grow and develop in your management role, you will encounter continuing opportunities to advance the skills you worked on in this first volume and to learn new specific business skills we will cover in the second volume, Management Skills for Clinicians, Volume II: Advancing Your Skills to Thrive in Administration. There you will learn more about enhancing your relationships and building a positive workplace culture on your teams and more broadly throughout your organization. You will gain familiarity and comfort with business practices for effective budgeting, financial management, hiring activities, and human resource management while building your momentum and growth.

Advancing your communication skills will help you grow and improve as you foster the growth of those you manage and lead. You will learn to embrace conflict and handle it constructively. Developing your business skills in hiring, human resource management, and financial management will help you garner and administer the resources that support your team’s important work. Recognizing and developing the strengths of you and your team members enhances performance and motivation to sustain your success as a health care manager.

Chapter Summary and Key Points

In this chapter, we looked at the dynamics of interacting with people at various levels relative to your position. We examined the importance of working well with your boss to understand her expectations, along with ways for you to align with her goals. We considered the importance of influence and relationships to build collaboration and offered approaches that can help you motivate others to want to work with you, especially when you have no authority over them to require them to support you. We looked at the benefits of building relationships in different areas of your organization and we suggested some actions and conversations to help you connect with others and begin to build relationships with them.

We conclude this chapter with an explanation of the core role of relationships throughout all your activities as you become an effective health care manager and continue to develop in your professional career. We summarized the skills you learned in this first volume, Management Skills for Clinicians, Volume I: Making the Transition from Patient Care to Health Care Administration. We offered a preview of what you will see in the second volume, Management Skills for Clinicians, Volume II: Advancing Your Skills to Thrive in Administration, where you will advance your relationship skills and learn additional business skills to help you thrive in administering your management responsibilities.

Key Points:

- You need to build relationships at work. You cannot do it all alone.

- Relationships are at the core of most of the skills you need to learn to become a successful health care manager.

- Much of the time, others are not required to do what you want them to do. You need to learn to influence them to want to collaborate with you.

- Your relationship with your boss is particularly important because he has power that shapes your success; he can bestow or deny rewards to you based on his perceptions of your performance.

- Demonstrate loyalty to your boss and respect the chain of command to keep your boss informed of what he needs to know.

- Find out what information your boss wants to receive from you and how to present it so it is clear and useful to her.

- To be successful in meeting your boss’s expectations, you need to make sure you know what her expectations are and that your goals align with hers. Organize your activities to discuss with your boss and get her feedback.

- Seek out people in other areas of your organization and get to know them.

- Your relationships throughout the organization are beneficial to your success as a manager.

- Do not be overly dependent on your boss. It is not necessary for you to direct every question to your boss when there are peers and others who can help you.

- Your other relationships can increase your value in helping your team when you learn about other resources and activities elsewhere in the organization.

- Enlist others to support you by inviting their participation in activities that are interesting and valuable to them.

- Remember to show appreciation for what others do well and express gratitude when others help and support you.

- As you grow and develop in your management role, you will encounter continuing opportunities to advance the skills you worked on in this first volume and to learn new specific business skills, which we will cover in the second volume, Management Skills for Clinicians, Volume II: Advancing Your Skills to Thrive in Administration.

Learning Activities for This Chapter

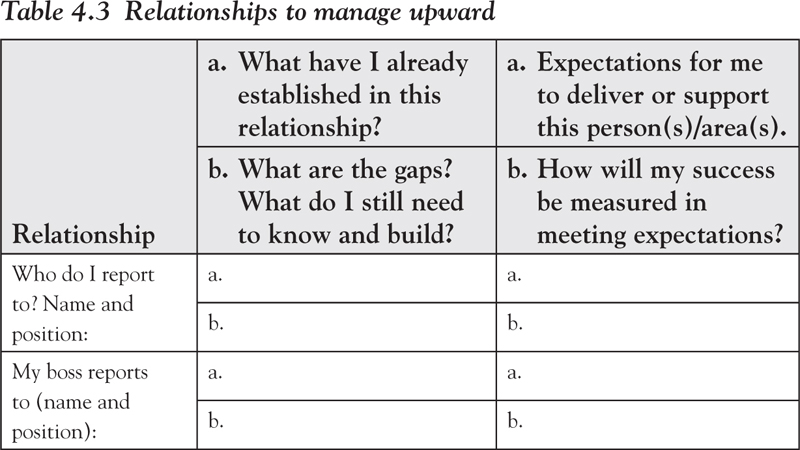

- Consider the relationships you have and those you still need to build, along with what is expected between you and others in these relationships. Filling in the tables below can identify gaps in what you need to know about your organization and your position in it, along with external channels you need to be aware of. Think about other information or clarity you need to answer these questions, where will you find it, and who can help you get it.

- Let us start with the relationships you need to manage upward, with your boss and your boss’s boss, as identified in Table 4.3.

- Who else are you accountable to, sideways (Table 4.4)? In other words, who are you required to deliver results to—who depends on you for information, coordination, project completion, problem resolution, and other areas? Consider both internal teams, external organizations, and others. What do these people or groups expect from you and your team, and how will you track your performance in meeting their expectations?

- What expectations for performance and behavior do you have for the people who report to you (Table 4.5)? How have you communicated these? Add a row for each key position and a few people in it who report to you, then complete the cells for each one.

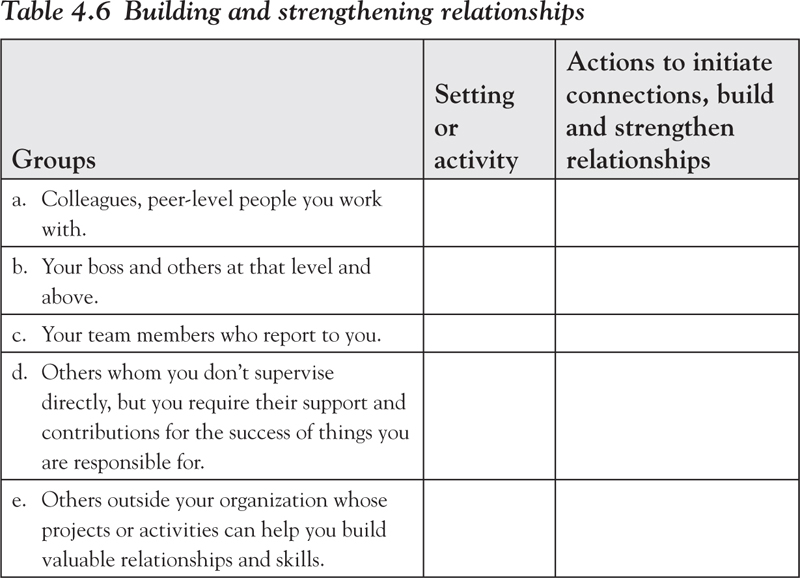

- Review the subsection, “Examples of Actions and Conversations That Build Relationships” in the last section of this chapter on building positive relationships. Who could you reach out to apply some of these suggestions to show appreciation, gratitude, or a desire to collaborate? What could you say sincerely and specifically to communicate clearly to the other person what you noticed and recognize him for?

- What opportunities do you see in your workplace to build and strengthen your working relationships with others (Table 4.6)? Consider the settings and activities where you could interact with these groups of people, how you could initiate connections and strengthen relationships. For example, you probably already interact with your peers in team meetings, and you might encounter your boss and others at that level in larger company meetings or by participating in special projects. What could you say or do that builds connections through these encounters and follow-up activities?

- How would you adjust the format and contents of Table 4.1, the Example Table of Activities to Track and Review that we showed earlier in this chapter, to organize your key activities, progress, and results to present them effectively to your boss?