Hiring and Engaging People in a Culture of Well-Being

Chapter Overview

Health care is all about people, who deliver treatment and keep the organization running effectively to meet the needs of the people we serve, our patients. In this chapter, we focus on these crucial human resources, the people who do the work on the team you manage. We will look at the value of creating a great place to work and the profile of a health care organization that built a work culture where people can thrive.

Then, we examine the specific things you need to do to hire people and get them started in their work on your team. We will look at how you hire, engage, and retain these people to do their best work. We show you the value of your human resources team and identify the things they can help you with, and when you must consult with them to hire new people and bring them onboard.

Topics in this chapter:

- The importance of people!

- What makes an organization a great place to work?

- Using strengths in your team

- Your roadmap to hiring and human resources

- Hiring: getting started

- Organizing your selection process

- Interviewing and selecting: What are you looking for and what should you ask?

- Compensation, terms, and job offers

- Welcome aboard and setting the tone

- Chapter summary and key points

- Learning activities for this chapter

The Importance of People!

Health care is all about people—treatment and care keep people healthy and well, and these services are provided by people trained as health care professionals who work directly with patients; they also work with and are supported by other people involved in indirect services and processes that keep the organization running. According to many reports, labor represents about 50 percent to 60 percent of hospital costs and is the greatest driver of operating expenses.1,2

Costs and Consequences of Turnover

Consider the consequences of losing people from your team, either due to ineffective selection or training or because they decide to leave and work elsewhere. Because of all the time we spend searching, selecting, hiring, training, and supervising employees, the costs of undesired turnover that occurs when they quit or need to be terminated are very high. Estimates of the cost of employee turnover vary widely because there is no standard methodology to calculate these costs. In several reports on general employee turnover across industries, the cost of replacing an employee is estimated to range from about 60 percent to over 200 percent of a person’s salary.3,4,5

There are some issues specific to health care, where salaries vary widely among health care professionals and specialties. There are costs of filling in labor gaps with high-cost temporary staffing to cover shifts—especially if you are working in facilities that provide 24-hour care—along with the decreased volume of revenue-producing activities that were being performed by trained and experienced people at high levels of productivity that new hires will not be able to reach without some time to learn and develop in their new roles.

Michael Rosenbaum (2018) reports average turnover in health care jobs in 2017 was 20.6 percent, up from 15.6 percent in 2010, and the turnover rate for bedside RNs in 2016 was 14.6 percent. As he explains,

This is an expensive problem: A study in the Journal of Nursing Administration found that it may cost anywhere from $97,216 to $104,440 in today’s dollars to replace a nurse, including pre-hire recruitment and aspects such as unstaffed beds, overtime and losses in productivity.6

An earlier study by Waldman et al. (2004) estimates the total loss due to turnover as more than 5 percent of the total annual operating budget.7 If a 5-percent loss sounds insignificant, consider the magnitude of this loss if your organization’s annual operating budget is $10 million: turnover would cost the organization over half a million dollars! What about a $100-million annual budget, or higher: the estimated cost would be $5 million or more. That could pay for a lot of care and treatment for patients and benefits to your very valuable and important employees who deliver and support that care.

Lower Turnover in Positive Workplace Cultures

Author Brené Brown (2018) learned this in her leadership research:

If we want people to fully show up, to bring their whole selves including their unarmored, whole hearts—so that we can innovate, solve problems, and serve people—we have to be vigilant about creating a culture in which people feel safe, seen, heard, and respected.8

The Great Place to Work organization surveys employees across industries to produce the annual FORTUNE 100 list of Best Companies to Work for in America and other Best Workplaces lists. From their 30 years of research, they conclude, “A Great Place to Work is one where employees trust the people they work for, have pride in the work they do, and enjoy the people they work with.”9 They define a “High-Trust Culture” as one where employees “believe leaders are credible (i.e., competent, communicative, honest), believe they are treated with respect as people and professionals, and believe the workplace is fundamentally fair.”10

A comparison of 2017 Best Place to Work data with industry data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that voluntary turnover in the health care industry was only 8.8 percent in High-Trust Cultures, far lower than the rate of 21 percent for all health care organizations.11

High trust in the work culture is associated with additional positive results for organizations. A Great Place to Work study found that the high-trust hospitals that made the 2016 FORTUNE 100 list of Best Companies to Work For had Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) patient satisfaction scores significantly higher than the U.S. average for overall hospital rating and whether patients would recommend the hospital. “As patients are the ‘customer’ in a health care setting, these results demonstrate the positive impact a high-trust culture can have on the overall customer experience.”12 To understand more about great places to work in health care, let us look at the profile of an organization that intentionally focused on becoming one by engaging its employees and supporting their well-being.

What Makes an Organization a Great Place to Work?

According to Carl Clark, MD, President and CEO of the Mental Health Center of Denver (MHCD), “It’s part of our strategic plan to create and maintain a Wellness Culture within the organization—a work environment where people can do what they do best and be supported.”13 “Wellness Culture” has shifted to “Well-being,” incorporating a holistic view of important areas of people’s lives as developed by Tom Rath (2010).14 The tenets of well-being have evolved and strengthen the organization’s enduring employee engagement.15

Recognition as a Top Work Place

A powerful indication that employees agree is that at the time of this writing, the organization has been placed among the Denver Post’s Top Work Places for 6 years in a row, 2013 to 2018.16 The most recent announcement explained how, in describing their workplace culture, many of the employers participating in The Denver Post’s 2018 Top Workplaces described their commitment to diversity and inclusion. Employees at MHCD stated, “We value strengths, diversity and new ideas.”17

Results of the very competitive contest are determined by employee responses to 24 questions in these areas:

- Alignment—where the company is headed, its values, cooperation

- Effectiveness—doing things well, sharing different viewpoints, encouraging new ideas

- Connection—employees feel appreciated, their work is meaningful

- My manager—cares about concerns, helps learn and grow

- Employee engagement—loyalty, motivation, and referral

- Leader—confidence in company leadership

- The basics—pay, benefits, flexibility18

Within these areas, employees are presented with questions framed as statements such as, “I believe the company is going in the right direction.” For each question, the employee selects his response from a 7-point Likert scale from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree.”19

Training Launched Cultural Transition

MHCD began to formally define its Wellness Culture in 2006, after our executive team, which I was working on, participated in a full week of engaging leadership training, at the suggestion of Joanie Gergen, our front office administrator at MHCD, who was offered a training class, “Pathways to Leadership,” free of charge by her friend at Verus Global. Throughout our journey to build a culture of wellness, the organization continued to measure and improve key indicators such as employee engagement and staff turnover.

Before the training, the organization had several other activities in place that supported this snowballing effort. We were already offering employees the opportunity to assess their strengths, using the Clifton StrengthsFinder assessment,20 and applying Garold Markle’s (2000) Catalytic Coaching21 as a more engaging and empowering employee coaching and development approach that replaced older traditional performance evaluation systems.

Beginning to Leverage Employee Strengths

After the training, we extended the efforts throughout the organization. All new employees received Tom Rath’s StrengthsFinder (2007) book, took the StrengthsFinder Assessment and received personalized reports of their top five strengths, which they could share with their managers and others.

For example, I learned that several of the people on my team were strong in “Deliberation,” which meant it was natural for them to think about the implications of new actions and initiatives before jumping into implementing them. So, as their manager, I learned that I could help them move forward by encouraging them to apply their tendencies toward thorough evaluation to evaluate risks appropriately and recognize the value of avoiding undesired harmful outcomes.

Another was strong in “Empathy,” so our team recognized his strength in being able to understand other people’s perspectives. We found it valuable to include him in planning in projects that would affect our consumers because he understood how they felt about the changes. We will look more closely in a later section at leveraging team members’ strengths for effective teamwork.

Our employee coaching forms were updated to include and leverage each employee’s top five strengths. We measured engagement every year and our Board of Directors held our Executive Team accountable for attaining and sustaining high levels of engagement, as measured by employee survey results.

Employee Engagement

Initially, MHCD measured engagement with a survey we conducted internally based on 12 key questions formulated through extensive research and analysis by the Gallup Corporation, as explained in Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman’s (1999) book, First, Break All the Rules.22 This set of questions provides an excellent gauge for measuring the strength of a workplace and establishing a culture in which managers focus on what people do best to help them be most effective and engaged at work. The feedback from the surveys was reassuring, but after conducting it ourselves for several years with limited information about respondents and the groups they belonged to in the organization, we found it difficult to make meaningful change in some areas. Later we began to work with an external survey with added customized questions and specific tracking and analytical capabilities. The larger external analysis helped us to identify more specific driving actions that managers could apply in their own teams to continuously improve results.

Jeff Tucker, JD, Vice President of human resources at MHCD, explained that in past years, around 2003, “The organization had turnover near 30 percent.” By 2014,

already high engagement scores have continued to climb, turnover now hovers in the low teens, and more importantly, employees are improving their alignment with the organizational goals of expanding services, helping clients recover, and spreading mental wellness throughout our community.23

Shortly after the leadership training in 2006, we engaged our managers in defining our Wellness Culture through an interactive process at an all-managers’ meeting, and all our managers agreed to the following tenets for “bringing out the best of ourselves and others:”

- Seeing everyone’s strengths

- Supporting and encouraging one another

- Celebrating staff, accomplishments, and diversity

- Respecting ourselves and others

- Listening to each other

- Creating an environment of healthy and positive relationships and community partnerships

- Believing everyone wants to be great

- Being passionate about our mission and having fun in the process

- Believing anything is possible!

Several themes are apparent in this collection of tenets. Notice the overall emphasis on strengths and possibilities, rather than on weaknesses and limitations. There is a strong emphasis on building positive relationships through listening, respecting ourselves and others, encouraging and bringing out the best in everyone. And the positive outlook with passion for the work we do and why we were doing it, with celebration and fun, certainly cultivated a sense of camaraderie and enjoyment that became apparent in the observable tone of the workplace. Outside visitors commented to our CEO that they were surprised by the laughter and smiling they observed, which was typically absent in earlier times and other settings where people did such challenging work for consumers with high needs and scarce resources available in the community to help.

Impacting the People Served

Roy Starks, MA, Vice President of Rehabilitation and Reaching Recovery at MHCD (2013), explains the significance of fostering a wellness culture for staff and its impact on the people served by those staff.

As with many community mental health providers, our initial focus was on the people we serve and how to help them achieve their life goals. Subsequently we began to more fully understand that our measures of recovery are really measures of human happiness and that, in short, consumer recovery is aligned with staff goals for happiness. This led to the understanding that the promotion of a wellness culture for staff is critical to the successful development of a recovery culture for the people we serve.24

As Roy explained when I met with him recently, this is a culture where the people working in it are making a difference, which shows up in meaningful outcomes that make a difference in consumers’ lives and saves money for society. It is important to bring it back to the mission.25

Meeting Needs and Realizing Dreams

As Carl Clark, MD, explains, “Getting people what they need drives down costs.” This refers to both the people we serve, whose health and well-being improve when we help them meet basic needs first and curtails the need for higher-cost care and services later, and our employees whose engagement and retention drives down the cost of turnover. As for helping our employees get what they need, financial well-being needs to consider the different needs of five different generations in the workplace. New graduates are concerned with basic financial needs, are carrying a lot of student debt. The organization not only provides attractive pay and benefits, but helps employees learn to manage financially. This relates to understanding people’s dreams from a comprehensive view. As recommended by Matthew Kelly (2007)26 in his book, The Dream Manager, asking employees about their dreams, including those for their lives outside of work, can help you understand their motivations and increase their commitment and engagement with a workplace that helps them attain their dreams.27

Diversity and Inclusiveness

Several years ago, the organization received feedback in a state-level quality review that we needed to strengthen our cultural competency efforts in treatment planning. The organization recognized an opportunity to go above and beyond a compliance requirement by leveraging our wellness culture to elevate the engagement of our workforce. In 2014, through an extensive nationwide search, we hired an energetic expert in diversity and inclusiveness, Leslye Steptoe, PhD, to join our executive team. Her training and inclusion initiatives quickly had an impact in further engaging our existing employees and attracting many new ones that enriched the multicultural fabric of our workforce.

Pillars of This Great Place to Work

The main elements that support a great place to work for this organization can be depicted in this model, “Implementing and Sustaining a Great Place to Work,” as shown here and illustrated in Figure 2.1:28

- Employee Strengths: The strengths-based approach that starts with each employee assessing his strengths and working with his manager on how to build and apply them at work.

- Putting Strengths to Work: Incorporating strengths into coaching and dialogue between each employee and her manager based on Markle’s (2000) Catalytic Coaching process.

- Engaging Everyone: Measuring employee engagement to identify drivers of engagement and providing actionable results to managers and their teams to increase engagement.

- Measuring Results: The organization measures engagement of its employees and the people it serves.

- Employee engagement surveys identify drivers of engagement and provide actionable results to managers and their teams to increase engagement and organizational effectiveness.

- The organization measures treatment outcomes as consumers’ progress in observable areas of their lives that reflect their recovery and through surveys of consumers about their own perceptions and feelings in areas that affect their progress.

We have seen in this section the philosophies (beliefs) and practices (behavior) that drove this organization to catapult its organizational culture from being better to being recognized as one of the best.

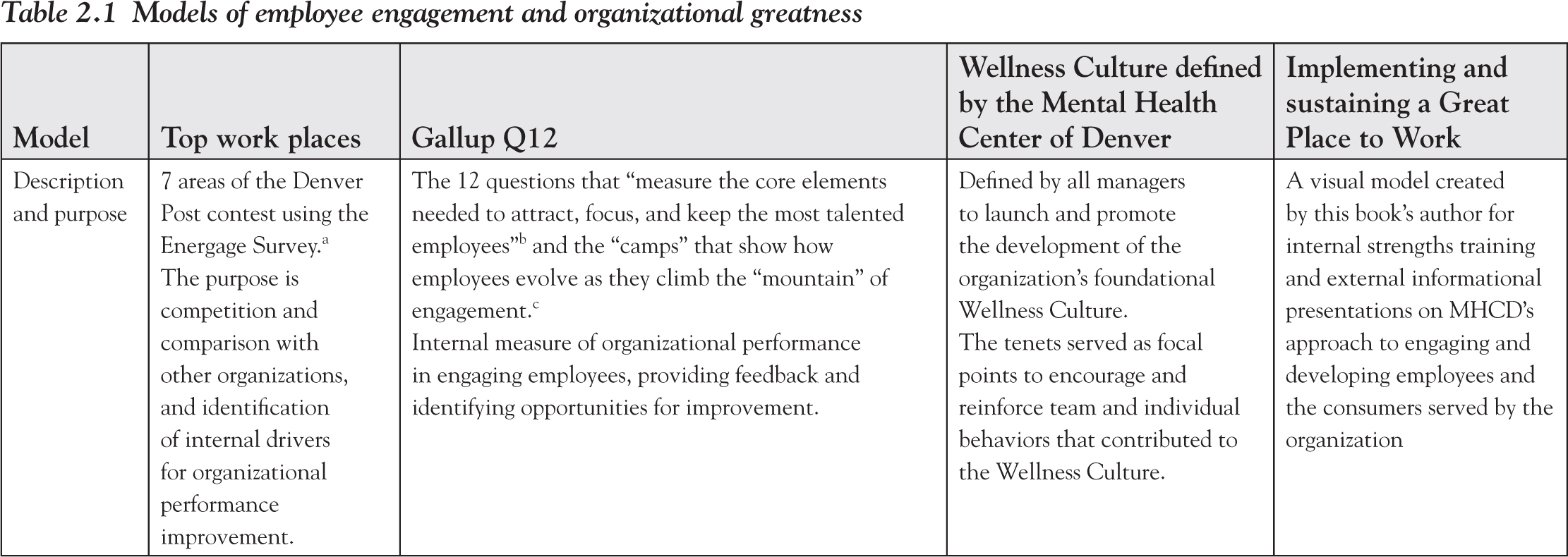

Unifying Themes

In this section about what makes an organization great, we have presented several different models and components that contribute to employee engagement and organizational greatness. Let us compare these different models and structures side by side, as shown in Table 2.1.

Although these are different models with different components, measurement scales, and purposes, they emphasize several common things in the components and purpose:

- Strengths, growth and development of employees

- Alignment, employees believing in the value of the organization’s mission and purpose

- Organizational effectiveness, quality work, and results

- Appreciation, recognition, and feedback

- Participation as demonstrated in the contents, development, and application of the models.

Next, we will take a closer look at what you can do yourself with the team that reports to you to leverage the strengths of your team members and increase their engagement.

Using Strengths in Your Team

Assessment Approaches

There are many different assessments used by organizations to determine styles and preferences of members of teams. Some mentioned by interviewees, among many instruments available, include Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, DiSC, Clifton StrengthsFinder, Kolb Learning Styles, and Emergenetics. As Carl Clark, MD, says, “The better you know yourself, the better you know what you need on your team.”29 Everyone has different preferred approaches, styles, and perspectives, and teams work most effectively when we recognize and utilize people’s differences.

Some assessment approaches include exercises and activities in which each team member participates in an assessment and receives a report or inventory of results, then the team works on solving a problem together. Usually this provides insights such as one I remember from an earlier setting where our team discovered that our most

decisive and forceful members initiated action and got other members to follow, but without the ideas and recommendations of the quieter and analytical members, the team headed off in an unproductive direction, and missed opportunities to pursue more fruitful paths to effective solutions.

Strengths-Based Leadership

More recently on my teams, we have used the approaches in Tom Rath and Barry Conchie’s book, Strengths Based Leadership.30 First, each team member completes a StrengthsFinder assessment of 34 possible themes to find out which are his top five themes. These top five themes are the things we gravitate toward naturally because we have focused on them throughout our lives. When we continue to utilize these themes, they become our strengths that help us perform effectively as we are doing what comes naturally. We feel more satisfied because our energy is directed more easily and we eliminate the struggles of trying to be what we are not. In the book, First Break All the Rules, Marcus Buckingham and Curt Coffman describe this approach as helping employees be more of who they already are.31 Doesn’t that sound smoother and more natural than trying to fix people?

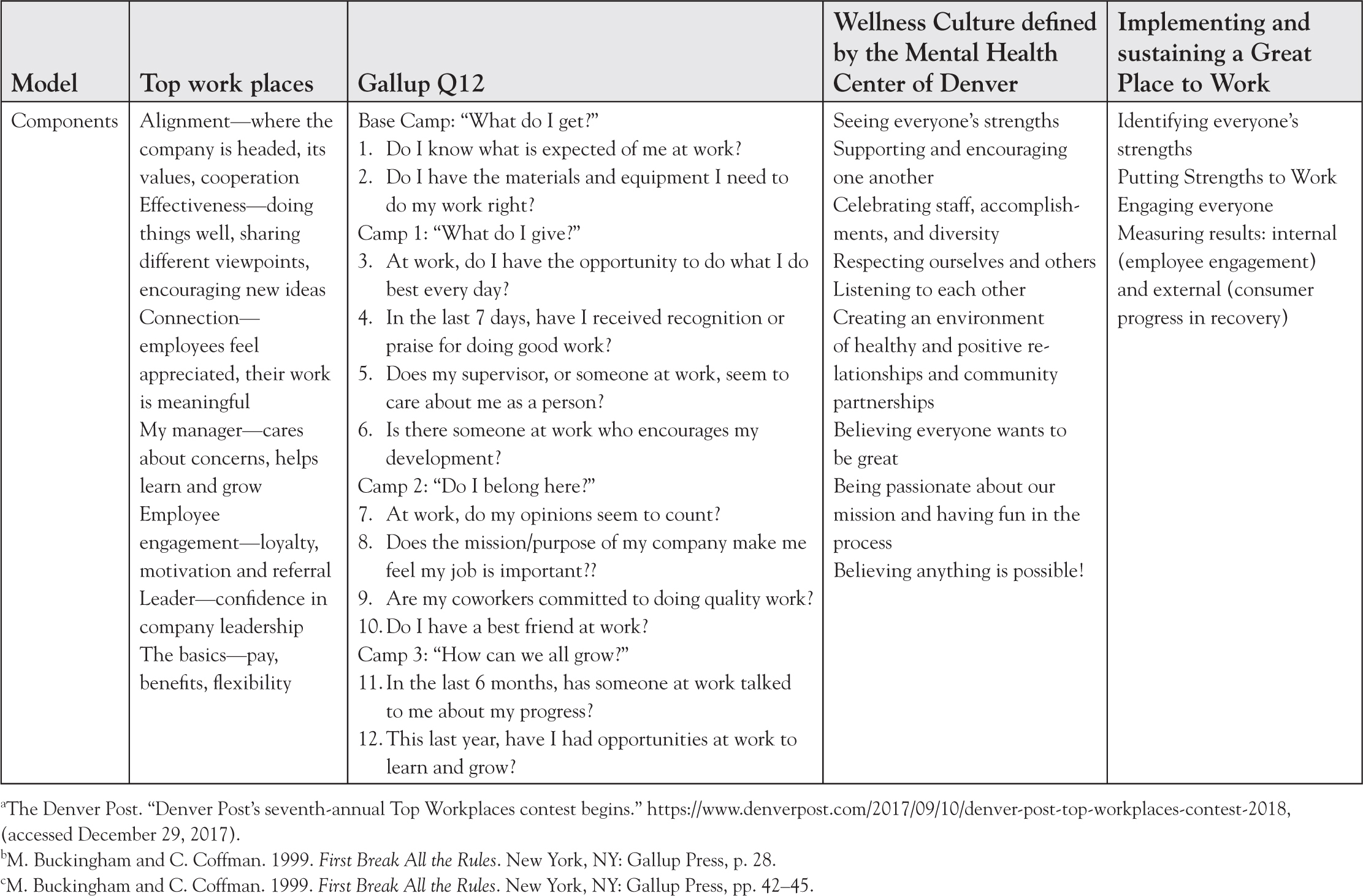

The Strengths-Based Leadership approach distributes all 34 of the themes into four domains:

- Executing

- Influencing

- Relationship Building

- Strategic Thinking

Within your team, you can organize all of your team members’ themes, including yours, into these domains, as shown in this example in

Table 2.2.

Discussion of this Team’s Strengths by Domain

This team was strong in the Strategic Thinking and Relationship Building themes, with much collective strength that involved analyzing, planning, relating to, and listening to others. Some collective strengths involved getting things done, and there was relatively little strength as a team in influencing others. This was not surprising, as this team’s function in the organization was largely strategic and analytical. They worked well with others, collaborated with other teams, and sometimes felt frustrated with the time and effort they spent in cajoling and overaccommodating the needs of other teams at the expense of achieving their own goals as a team.

The team discussed this honestly and agreed to use its collective strengths in Relationship Building by utilizing the team members who were strongly oriented to this domain to build relationships with others in the teams they needed to influence to help this team reach its project goals. They used some of their strengths in idea-generation and planning to brainstorm about how they would approach other teams; then they developed a schedule for ongoing visits to the other teams to enlist their cooperation. This strengthened collaboration with other teams and helped achieve better results and more timely completion of this team’s project goals.

Strengths-Based Employee Development

This approach can also be useful in your ongoing coaching and development with your employees. First, you get a better understanding of your own style and strengths and how you can use them to lead effectively. Second, you learn more about each of your employees and what they need from you based on their top themes that emerge. And third, you can help people identify others to work with who might help them complete an effective set of collective strengths. For example, an employee who gravitates toward generating ideas and building relationships but is not oriented toward planning and completing projects might benefit from using her relationship strengths to find someone to team up with who can help her bring her ideas to fruition.

Strengths-Based Teams

A key philosophy in this approach is that individuals do not have to be well-rounded, rather, focus on how to round out your teams. In other words, appreciate your employees for who they are and what they do well, and do not try to force them to be different. At the team level, look for ways to fill in areas where your team does not have collective strengths. Help to identify people, systems, and approaches that can help the team to be effective.

And when it is time to hire some new team members, you might want to consider actively seeking people who are strong in areas that would round out your team. In later sections on hiring, we will see how you learn how people have applied what they do best in past situations so you can enlist them to enhance your overall team capabilities. We will also examine more closely how you can coach and develop your employees.

Your Roadmap to Hiring and Human Resources

For the basic process for attracting and developing the people you need to keep on your team, follow these steps, which we will explain further in later sections. You may use this roadmap as a checklist to make sure you have covered the necessary steps.

- Develop positive working relationships with all of your current team members.

- Concentrate on taking charge and managing effectively, building relationships, and communicating. For help, see Volume I (LaGanga, 2019), particularly Chapters 2 and 4.32

- Build a positive culture on your team by applying principles like those described in our earlier section, “What Makes an Organization a Great Place to Work?” developed by a Top Work Place winner, as profiled in that section.

- Identify and focus on the strengths of your team members as described in the earlier section, “Using Strengths in Your Team.”

- Evaluate hiring needs as positions are vacated.

- Communicate with your boss for input and to keep her in the loop.

- Proceed to Hiring when appropriate.

- Hiring

- Contact your human resources department and follow procedures to register a current employee’s intention to terminate, then open the position for rehiring.

- Review the current job description, adjust as needed.

- HR posts and advertises the position through recruiting channels.

- Disseminate the position description and posting to people in your network of contacts and other hiring pipelines to encourage suitable candidates to apply.

- Review applications with HR as received, or in batches to compare and select.

- Screen applicants for their match with required qualifications (HR and you as hiring manager).

- Organize an interview team and Round 1 of interviews.

- Select an interview team (roughly three to eight people, teammates and representatives of related teams).

- Schedule hour-long interviews followed by debriefing times afterward and another time to select finalists.

- Develop behavioral interview questions to assess job candidates’ abilities to handle the job and work productively on the team.

- Request input on questions from the interview team.

- Collect and consolidate into interview questions (no more than 12, and allow time at the end for the candidate to ask questions).

- Conduct interviews using the same set of questions for every candidate (to allow objective comparison); complete scoring sheets (developed by you or HR).

- Meet with your interview team to evaluate Round 1 interview results and select finalists (two to three) to present to the interview team for Round 2 for further skills demonstration (if relevant) or to your boss or other final selection team.

- Round 2: Invite finalists to demonstrate key job skills (such as treatment planning with a patient, conducting a training session, or presenting on a relevant topic.)

- Meet with your interview team to select the final candidate to offer the job to, rank order candidates, and determine whether alternatives would be acceptable if your first-choice candidate declines.

- Communicate with first-choice candidate (and other serious contenders) to confirm their interest and keep them engaged with you and your team.

- Conduct reference checks (HR department or you) and background checks with verification of licenses, credentials, criminal/fraud checks as appropriate for the position (HR).

- Determine salary and terms of offer with HR for your selected candidate.

- Work with HR to present offer and discuss terms and start date (you or HR, depending on the standard hiring practices in your organization).

- Finalize offer and start date, send confirmation to your new hire!

- Prepare for employee arrival

- Notify other departments who need to enroll the new employee in electronic systems for name badges, facility access, computer access and usernames, and to prepare work space and equipment.

- Enroll the new employee in needed training for computer systems, electronic health records, policies and procedures as soon as available after the employee’s arrival.

- Onboarding and startup: New employee arrives!

- HR introduction to necessary payroll processing and paperwork.

- Organization’s new employee orientation to procedures and culture.

- Welcome lunch with new employee (you, one-on-one, or according to your organization’s practices which might be a collective event for all new hires together).

- Introduce employee to workspace, team members, other staff, and tour relevant parts of the facility.

- Assign a teammate to help and support the employee, arrange job shadowing as appropriate.

- Schedule and communicate times with employee for supervision meetings with you, other meetings with your teams, and other standard meetings.

- Ongoing engagement

- Meet regularly with your employees to ask how they are doing, help them get questions answered or obtain needed tools and supports, talk about their goals and progress.

- Provide feedback, share observations with praise on successes, and guidance where improvement is needed.

- Continuing coaching and development.

We will discuss more below!

Hiring: Getting Started

Let us look at what we need to do to manage our human resources effectively, to select and develop the right people for our teams to help ensure we do not lose them unnecessarily. Effective hiring is an important first step. As Darcy Jaffe, MN, FACHE, Chief Nursing Officer at Harborview Medical Center, commented, “If we do make mistakes in hiring, people don’t stay.”33 She and others help us avoid those mistakes as they offer suggestions for developing and engaging our employees.

Develop Positive Working Relationships

In earlier chapters, both in Volume I and in this volume, we looked at how to build effective working relationships with the people who were already on your team when you started in your management role. We saw that there could be some particular challenges because you did not choose these people to join your team and report to you, and quite possibly, they did not choose you, either! Yet, you learned what to say and how to get along and lead with the people you had, who could be very helpful assets because they already knew how to do their jobs, get things done by following the processes and guidelines within the organization, and work effectively with others on your team and throughout the organization. Your positive working relationships foster a team environment that is helpful in retaining your current team members and attracting new ones for positions that open.

Now, as a manager, there will come a time when positions open up on your team and you will find and select new team members to fill them. These openings, also known as vacancies, occur because someone leaves, or there is growth that requires additional staffing in the form of new or additional positions, or there is some organizational restructuring and you inherit some vacant positions from another part of the organization. Let us start with the most straightforward of these, when an existing staff member leaves, perhaps because he is promoted out of his current role, or transfers to another position in the organization, or leaves the organization to move away, join another organization, return to school, retire, and so forth. Where do you begin?

Communicate and Evaluate Rehiring Needs

When someone turns in her resignation or communicates to you her intention to vacate her position, it is a good idea to let your boss know, along with your thoughts on how to manage the change and fill the vacancy. This is part of the expected practices of courteous and proactive communication that we discussed in earlier chapters, particularly in Volume I, on managing up and building a productive relationship with your boss.

It is also an opportunity to demonstrate your initiative in planning proactively, as you may have some ideas on how to rearrange work or eliminate unnecessary steps, so you might be able to delay refilling the vacancy right away to save the organization some expense. Or you may already know of potential candidates who have expressed interest and would be valuable additions to your team.

Contact Human Resources

Your human resources department has established procedures for handling terminations and for proceeding to fill those vacant positions. So, you will need to contact HR to ensure you follow their requirements for processing the termination or transfer of the incumbent employee and opening up the position to be filled. The process might include getting a formal letter or e-mail from the departing employee to document his resignation and the date he intends to vacate the position. You may request reasonable notice, usually at least 2 weeks. Some employees will be willing to stay longer to help finish open work with patients and transition responsibilities to other team members or a new employee.

This is where it is helpful to have positive and mutually supportive relationships with the people who report to you, so they want to continue to support the good work of the team they are transitioning out of. If she is moving to another position within the organization, consider negotiating with the employee and her new manager to be able to extend her transition time or borrow some time after the transition for her to consult and help train her replacement.

Evaluate and Plan for Refilling

Next, when the position is officially being vacated through the proper notice and documentation, you may proceed to get the necessary approvals to open the position to refill it. Sometimes, especially if budgets are tight, organizations require a review of vacant positions to make sure they really do need to be refilled at the same level and salary range. When there are projected budget shortfalls, due to revenue shortages or higher-than-expected expenses, positions may be frozen temporarily or consolidated with other positions to reduce headcount as part of streamlining organizational operations to boost efficiency and manage costs. Messmer et al. (2008) recommend that you assess your staffing needs in terms of your department’s priorities. Consider whether you need to rehire or could reposition staff and duties to fill gaps.34

Review the Job Description

In any case, you need the approval of the HR department to open the position for refilling and to post the job, which means announcing it and advertising it to attract applications. Be sure to review the job description for accuracy and to determine if any of the requirements or desired qualifications have changed. For example, are there any special skills or certifications required by new grants or funding requirements? Have any regulations changed or relaxed that can either restrict or expand the range of qualifications?

Messmer et al. (2008) recommend that you be specific about the tasks the employee will perform and differentiate those from qualifications, which are the skills, attributes, and credentials required. Be clear about degrees and licenses that are required to do the job. Remember to consider the soft skills, such as communication and teamwork, which are important for an employee to work successfully in the position.35

Begin Recruiting with Posting, Advertising, Dissemination

Double-check with HR and others to ensure that the job description and announcement are clear and accurate; this will save time later having to screen out unqualified applicants or having to re-announce the position because it did not attract enough qualified candidates who would be valuable assets working on your team.

Now you are ready for HR to post the job through its recruiting channels such as hiring websites, your company web pages on hiring and open positions, and the trade organizations and professional associations that the organization belongs to and works closely with. You may distribute the announcement directly to your professional contacts and post to professional groups such as your alumni association and professional societies related to the disciplines and training of the candidates you seek.

As Messmer et al. (2008) remind us, there are benefits in filling jobs from within the organization; this can reduce turnaround time and cost of filling the position, boost employee morale, and enhance productivity with employees who are already familiar with the organization. But do not limit yourself to internal candidates. External recruiting is valuable in broadening the selection of talent, opening up to fresh perspective and new ideas, and increasing workforce diversity.36

Organizing Your Selection Process

Fairness and Employment Laws

To ensure fair access and opportunities for employment for qualified applicants interested in a position, it is important to follow consistent steps and content to assess applicants for the position. Be aware of the employment laws that apply to the country and location where you work. In the United States, for instance, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) enforces federal laws that prohibit discriminating against a job applicant or employee because of the person’s race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy, gender identity, and sexual orientation), national origin, age (40 or older), disability, or genetic information. The laws apply to hiring, firing, promotions, harassment, training, wages, and benefits.37

Be aware of additional laws that protect people with disabilities from discrimination and exclusion from employment in which they are able to perform the essential functions of the job, with or without reasonable accommodations from an employer. According to the laws of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), “If an employer has prepared a written description before advertising or interviewing applicants for the job, this description shall be considered evidence of the essential functions of the job.”38

Keep in mind these requirements when you conduct your selection process and pose questions to candidates. This is another reason to work closely with your HR department whose members are familiar with the laws and requirements and know how to make sure the essential functions are justifiably required for the job and clearly included in position descriptions. Also, they can help you determine what reasonable accommodations may be appropriate for candidates or employees with disabilities.

Focus on the requirements of the job and make sure you can explain how your assessments and questions relate to those requirements. You should never ask applicants about any of the characteristics listed above with EEOC; to do so could leave you open to complaints of illegal employment discrimination. For example, you may not ask candidates their age, whether they plan to become pregnant, which religious practices they follow, whether they have disabilities, or other questions targeted to identify their membership in groups or characteristics protected from illegal discrimination. Instead, you should stick to the requirements of the position, clearly communicate about key aspects such as the work schedule and any expected conditions such as long shifts and required overtime, and ask candidates if they can work with those conditions.

Review Applications and Conduct Screening

In your next step, you will review applications and resumes to determine which applications and candidates appear to be best suited to the requirements of the position and work setting. Your HR department will help and might perform initial phone screening interviews for you.

The initial screening should verify that candidates acknowledge having the necessary qualifications including professional degrees, licensure, training and certifications, skills, and experience, and that their salary expectations fit within the range for the position. Later, for candidates who are finalists or selected for hiring into the position, background checks and other evidence will be obtained to confirm that the credentials are valid and current, with no disqualifying events or exclusions from state or federal payor sources and regulatory groups.

You may conduct further screening interviews or individual meetings yourself to do deeper assessments of applicants’ qualifications for the position along with their motivations and suitability for working in your organization on your team and reporting to you. You are selecting and narrowing the set of those you will present to an interview team for deeper assessment of work styles, attitudes, some specific skills and capabilities, and compatibility with the organization and team.

Organize Your Interview Team and Questions

In the meantime, you can be assembling an interview team to represent your team and other relevant areas of the organization where people will work closely with the person you hire or have a stake in the person’s successful performance in the job. Some interview teams include patients or other people outside your organization who can help assess candidates’ suitability from other perspectives. Create interview time slots when all members of the interview team can be available so that you obtain complete sets of comparisons from all interview team members.

Create or select questions to ask candidates to find out more about their approaches to work, how they treat patients and work with others in the organization, and the compatibility of their goals and values with the mission and vision of your organization and the goals of your team. Rowley and Jackson (2011) and Sisson and Storey (2000) recommend that you structure your interviews to ask the same set of questions to each candidate to provide a basis for comparison. Include questions that ask about previous experience and others that are more situational or problem-solving to find out how candidates would handle real or hypothetical problems that are relevant to the job.39,40

Interviewing and Selecting: What Are You Looking

for and What Should You Ask?

Confirming Matches with Basic Requirements

Different kinds of questions serve different purposes. Simple yes-no questions are closed-ended; they merely ask for confirmation or denial of specific information.41 These can be appropriate in brief screenings, with questions such as,

- “Is your bachelor’s degree in nursing?”

- “Do you have prescriptive authority?”

- “Are there any limitations or exclusions on your license to bill your services to Medicare?”

- “Have you worked in an outpatient setting before?”

- “Are you licensed to practice physical therapy in Colorado?”

- “Did you complete your residency at Mass General?”

Of course, unexpected yes-or-no responses would prompt the screener to ask for more explanation that might result in a candidate being disqualified from further consideration.

Behavioral Interview Questions

Now let us consider how you can fill in more of the unknown picture of how the person will really perform when she comes to work on your team. Behavioral interview questions are designed to use information about people’s past experiences with real tasks and problems.42 The candidate’s responses can reveal what she is likely to do in future situations she would encounter in the position. You can design them from realistic situations in your workplace. Often, they are worded as a request, such as “Tell us about a time when . . . And what did you do?” Here are some examples.

- “Tell us about a team you worked on and what you did that helped it work well.”

- “Now tell us about a conflict you experienced with someone you worked with. What was the situation, what did you say and do, and how did it work out?”

- “Tell us about a patient you worked with who ignored your recommendations and their condition worsened. What did you say to them and how did they respond?”

Notice how the behavioral questions ask about what the candidate actually said or did in the situation, not what they believe philosophically or theoretically should be said and done. This can reveal several things. Does the person really have experience in this area, or is he just describing what he thinks people should do if they found themselves in that situation? Listen for clues such as generalities and references to others rather than themselves, such as, “Teamwork is important. It helps when everyone pulls their weight and supports their teammates.” Contrast that vague response with this more specific one:

On the team I work on now, people tell me they appreciate my pitching in when things get busy and tense. Yesterday when I was caught up on my rounds, I helped a new nurse who was struggling to give an injection to a frightened elderly patient.

Another strength in the second response is the recency of the reference to things in the candidate’s current work and something she did just yesterday.

The second behavioral question shown in the preceding text can help you learn more about the candidate’s style of communicating and working with others, along with her willingness to talk about difficult things. It is not unusual for candidates to respond to a question about conflict or things they perceive as negative by denying that they have ever experienced them. Such a response might sound like this: “Oh, I don’t have conflicts, I get along with everyone!” This is where it is appropriate for you to probe further with follow-up responses. One could be, “What do you do to prevent conflicts? Can you talk about a time when you needed to do that?” Or another could be, “How about when you disagreed with someone else you worked with? What was the situation and how did you work it out?” Again, look for their specific references to themselves and their own behavior—are they able to take responsibility for their own actions or is there a tendency to blame problems on others?

Perhaps you asked the third question, about the patient who ignored recommendations, because this happens a lot in your clinics and team members who are too forceful with their patients run into problems. The candidate’s response could tell you about her experience and likely approaches so you can determine how effective she would be.

Oh, I remember that happened early on when I was just starting my practice. I had a stubborn patient who tuned out all my efforts to explain to him why he needed to take his medication. After he ended up in the hospital, he admitted he was tired of my nagging and wished he’d listened to me, but he had a hard time understanding my detailed explanations. I learned a lot from that, ended up apologizing, and asked him what kind of information would be more helpful to him. It turned out he preferred to read written instructions rather than listen to long oral explanations, so we agreed that I’d just tell him briefly what the medication was, print out the order with instructions, and he began to follow my recommendations. Now I ask my patients what would be helpful to them and since I started listening to them more, I get less resistance from them.

Open-Ended Questions to Delve More Deeply

Open-ended questions require more than a simple yes-or-no response and are designed to elicit more information and reveal details that you need to know. For example, asking, “I see you’ve been a licensed therapist for 15 years. In what state are you licensed now?” could reveal that the person has started the paperwork and is license-eligible but not yet licensed in your state, so there could be delays in his eligibility to submit billable services in your organization.

Open-ended questions also can delve deeper about people’s attitudes, preferences, and approaches. First, consider how a closed-ended question such as, “Do you enjoy working on teams?” makes it easy for a candidate to simply tell you what she thinks you want to hear by responding with, “Yes!” or an enthusiastic “Yes, of course, I’m a real team player!”

Or, “Do you get frustrated with patients who ignore your recommendations?” might help you know how honest they are if he replies with, “No, I never get frustrated with any of my patients!” or “Sometimes, but I don’t let it bother me.”

Now consider how much more you could find out by asking an open-ended question such as these.

- “What did you enjoy about teams you’ve worked on, and what were some of the challenges?”

- “What do you say to a patient with a serious health problem who has ignored your recommendations and his condition has worsened?”

Exploring Styles and Approaches

With open-ended and behavioral questions, there aren’t necessarily right or wrong answers; you are trying to get a sense of what it would be like to work with this person, how he would get along with others he will be working with, and how effective and successful he is likely to be in your particular organization. As Darcy Jaffe, explained, “I want people with a sense of joy in the world, who have hope and optimism and can transmit that.” In selecting and hiring new nurses, she looks for what people find fulfillment in, to determine whether they are a good match with values of the organization and its mission, which has been in place for over 50 years and “permeates everything we do.” It is about taking care of people from all walks of life.43 She looks at the attitudes people bring to work because of their impact on wellness on patients and the workplace, and finds out how candidates regard various populations of patients. So, it would make sense to ask questions that can reveal people’s attitudes, beliefs, and preferences and the ways these affect their approaches to work.

Consider candidates’ styles of communicating and working. If your organization is highly collaborative and a candidate reveals strong tendencies to issue commands to team members and compete with others in the organization, will that make it hard for the person to earn the cooperation of others to get things done? If the person is very laid-back and casual in a fast-paced environment that relies on formal hierarchies and established procedures, will that lead to problems? Or does the person offer special differences likely to bring benefits to the organization if she can effectively influence others to adopt new ways of doing things?

Having a different style from others on your team might even be a good thing if it can help the team work through conflict constructively and arrive at better decisions. Do you see risks in hiring this person and do you see valuable enough benefits to justify the risks? How much are you, as the person’s supervisor, willing and able to support such contrasts in style and approach to ensure that your overall team operates effectively with productive relationships among all the members?

Skills Demonstrations

So, you have screened candidates to ensure they have the required credentials and qualifying skills and experience, and selected some for further interviews to explore how well they would work in your organization and team. How do you finalize your decision so you can proceed to offer the job to the most appropriate candidate(s)?

For some positions, you may need to go beyond even behavioral interviewing questions so you can see exactly what the candidate can and would do if hired. You can narrow the group of finalists to a few and ask those two to three to prepare a presentation or demonstrate a key skill relevant to the actual things they would be doing on the job. For example, having the candidate show the interview team how she does treatment planning with a patient, or conduct a training session on a topic related to the position, allows members of the interview team to play the role of people who would be interacting with the person after he is hired, to ask questions and experience firsthand exactly how the candidate responds. This will reveal important qualifications such as ability to convey caring and respect with patients, presentation and training skills, ability to explain things clearly, respectful interaction with class participants and ability to handle conflict or challenges in a training setting with employees in other roles in the organization.

Role plays of other situations may be appropriate depending on the position. For example, for a patient advocate or position that conducts patient education group sessions, you might want to role play some typical scenarios the person would encounter in the position; you could include interview team members, or actual patients, to play the role of patients.

Selecting the Right Candidate for Your Position

All of these assessment activities, from screening to interviews to presentations and role plays, give you plenty of valid information to differentiate among candidates, fairly and legally, by applying the evidence you gather directly to the job requirements. If conducting training is an essential function of the job but some candidates lack effective training skills, you are justified in eliminating them. If your patients require a certain level of support and monitoring but some candidates are unwilling or not capable of providing that support, then you have reason to eliminate them.

Often, it comes down to several candidates having the identified skills and abilities needed for the job, or there may even be one that stands out as most qualified, but you detect something concerning that could become problematic. What should you do?

Getting More Information

Several interview participants offered advice on this situation. Dixie Casford, VP of Acute Care at Mental Health Partners, described a time when an interview team had some concerns about the communication style of the candidate they found most qualified. They handled it honestly by sharing their concerns directly with the candidate and asking him to respond. The candidate admitted this was an area he had been working on and described the progress he was making. This opened the kind of honest dialogue we described in earlier chapters with the candidate offering permission for others to offer feedback if they felt he was getting off track. The interview team appreciated the candidate’s self-insight and willingness to accept feedback, the candidate was hired, and was very successful in his role.44

Vicki Rodgers, Chief Operating Officer at Mental Health Partners, mentioned “red flags” she had seen through many years of interviewing and hiring. Sometimes, she explained, an interview team wants to hire someone, but as the hiring manager, you might have a feeling that there is something problematic about the candidate. She strongly recommends that you always check further. If you have concerns about their skills in some areas, ask for further evidence such as writing samples or showing you how they perform particular tasks. Delving into reference checks and talking to others who have worked with the person can help you find out what you need to know.45

New information might not necessarily eliminate the candidate from consideration. Rather, it might reveal things that can be discussed and worked out ahead of time with candidates so they do not become problems after they are hired. For example, maybe in the past a candidate was overly demanding with employees and this caused hard feelings and the exit of some key employees. Or, another candidate struggled to hold people accountable and this caused a past team to miss meeting some key deadlines. Asking about such issues can help identify patterns that signal future problems, or might reveal the candidate’s ability to learn from her mistakes and convince you of her self-insight and commitment to improve. Perhaps you would require the candidate, as a condition of employment, to complete some education or training or participate in developmental activities to address a weak area.

Reference and Background Checks

A formal reference check is normally part of confirming your final selection before you offer a candidate a job. It usually includes talking with at least three people who have worked with the candidate to confirm positions the candidate held, ensure performance was good, and she got along with others. Ideally, you would like to include some people who have directly supervised the employee, but often a candidate will not allow you to talk to his current boss because he has not let that person know he is planning to leave his current job.

Reference checking involves some time and expense, especially when it includes verification of licensing and other credentials. Some positions require criminal background checks and verification that the person has not been excluded from providing treatment or billing payers such as Medicare. Thus, it is normally done at the end of your interview and selection process for the final candidate, or when you have a few final serious contenders for the position. In most organizations, the HR department conducts the final reference and background check. Some organizations leave the reference check to the hiring manager, or you might conduct it earlier if you detect discrepancies or foresee potential problems, as described above, and want to probe for specific information.

HR Adds Valuable Wisdom and Experience

You should always pay attention to feedback from your human resources team. Jeff Tucker, VP of human resources at the Mental Health Center of Denver, reminds us that the HR team interacts with candidates throughout the process when you are not there. They know if candidates are courteous or dismissive to the receptionist when they arrive for their interviews, prompt or tardy in responding to communication, professional or overly casual in their interactions.46 If there are problems occurring with some candidates and their interactions with others in the organization before they are even hired, when they should be on their best behavior, what will they be like afterward?

Our HR team helped us avoid a serious problem when a team I was managing had a difficult time finding the right candidate for an open position. After many unsuccessful interviews, my team finally settled on a finalist and presented him to me for a final interview. I shared the enthusiasm of the hiring manager and her team for this candidate, who was very likeable, interviewed well, and demonstrated strong knowledge of the function he would be working in. At the final steps of working with HR to prepare an offer, the hiring manager received a call from our HR manager, who started with, “Oh, my,” and we knew it was not good news. “I’ve never seen anything like this.” He shared with us the results of the reference check and background check, with state arrest records, that corroborated the candidate’s experience in a similar earlier job . . . Where he had been accused of theft, had committed other unethical activity, and accumulated a history of criminal activities that were incompatible with the standards and requirements of our position. Our collaborative HR manager never told us we could not hire this candidate, but we could clearly decide based on the evidence that we certainly should not!

It does take time and effort and it is better to wait to find the right candidate for the position you are filling rather than hire just to get a position filled. You should never settle for less than the best when hiring. Bringing in the wrong people can do much harm to your organization, and as the last example demonstrates, can put the organization at serious risk of harm. In that case, we waited and eventually found an excellent candidate, who happily accepted our offer and thrived in the position.

Compensation, Terms, and Job Offers

As shown in our roadmap above, you will work closely with your human resources department to determine an appropriate salary, terms and conditions, and present the job offer to your selected final candidate. As much as you may want to advocate for maximum pay and the most favorable terms for a candidate you view as especially valuable, you cannot determine salaries and benefits without the involvement and support of your HR department, which holds the responsibility for ensuring fair and reasonable salaries among job categories across the organization, based on required credentials and experience and in consideration of market comparisons for equivalent jobs in other organizations in your hiring location.

Positions are often organized into job groups or families that may contain entry-level and more senior levels of experience or credentials—for example, Imaging Technician I–III, or Case Manager I–II. Pay ranges, benefits, and other terms of employment usually follow standard guidelines for specified salary grades associated with increasing levels of responsibility and compensation in the organization. HR will work with you to determine the correct level that matches your selected candidate’s credentials and experience, and an appropriate point within the salary range. Often there is consideration for a candidate’s current salary, and it is desirable to offer the person your position at a point that is somewhat higher than her current salary if that is possible without creating inequities compared with other team members with similar credentials who have been working in the organization awhile. This is where you really need the perspective of your HR team to compare salaries in positions of similar skill and responsibility across the organization to ensure fairness. Usually you will avoid offering a salary at the very top of the range for the position because it is desirable to leave some room for growth of skills and annual increases.

HR will also ensure compliance with labor laws and any special labor contracts, such as an employee labor union contract, in effect in your organization. You will need to work within the hiring budget for your team or department. Going beyond the limits of your salary budget may require special approval from your accounting and finance department, and will likely require that you delay other hiring or reallocate expenses from somewhere else to offset the additional expense and ensure that the overall budget balances.

Welcome Aboard and Setting the Tone

The important word here is “welcome!” You want your new employees to feel comfortable, wanted, and supported when they arrive and get started. The process is referred to as onboarding to help new employees assimilate into their new organization and roles.

Most organizations offer some kind of formal orientation and introduction to company policies and procedures. Even better is for you to connect in person with everyone you hire who reports directly to you. Show them around when they arrive, introduce them to others. If you cannot be present and available when they arrive, make sure you have assigned someone to do this. Take your new employee to lunch on the first day or make sure the person is included in lunch plans with other team members or a group orientation activity for all new employees.

Darcy Jaffe, who has high retention rates with very few employees leaving her teams, explains that in her organization, new hires get mentors and metrics. So, they know right away what they need to do and they have someone to help them learn how to do it. Departmental goals are assigned to new people with follow-up on a monthly basis. They review these with their managers and set improvement goals.47

Chapter Summary and Key Points

In this chapter, we looked at how an organization built a strengths-based culture of well-being for its employees. You can adjust and adopt these approaches to build a positive culture in your workplace. By focusing on employees’ strengths, you can attract and select people to join your team who will bring value to your team and complement the strengths of your other members.

You saw a hiring roadmap that helps you navigate the steps of the hiring processing as you find and select the right candidates to fill open positions, and learned how your human resources team can help you as you build and develop a cohesive team of capable and engaged members!

Key Points:

- People are valuable! According to many reports, labor represents about 50 percent to 60 percent of hospital costs and is the greatest driver of operating expenses.

- When people leave to work elsewhere, turnover costs are very high with searching, selecting, hiring, training, and supervising employees. Choose wisely and set a positive tone for the people you hire!

- It is worth building a positive work culture; such workplaces enjoy much lower employee turnover.

- You can contribute to high trust in your workplace by being a leader who is perceived as competent, communicative, honest, respectful, and fair.

- Focus on what people do best to help them be most effective and engaged at work. Emphasize strengths and possibilities rather than weaknesses and limitations.

- When hiring and developing your team, look for ways to fill in areas where your team does not have collective strengths. Consider how to round out your teams by adding people with valuable strengths to complement those already on the team.

- Include other people in your interviewing and selection process, especially those who will work closely with the person you hire or have a stake in the person’s successful performance in the job. Some interview teams include patients or other people outside your organization who can help assess candidates’ suitability from other perspectives.

- When positions open up on your team, be sure to communicate with your boss and your human resources team and make sure you cover all the necessary steps in hiring.

- Utilize your human resources team. They have wisdom and experience to help you make good hiring decisions, set fair and appropriate salaries, and avoid legal problems.

- Past behavior can help predict future performance. Ask open-ended questions to find out what candidates have actually done and how they are likely to respond in your workplace.

- Seek additional information to resolve questions or concerns about job candidates. Pay attention to reference and background checks.

- Make your new hire feel welcome and set the stage for her success. Arrange to meet and greet her on the first day and connect her with teammates who can help her get started.

Learning Activities for This Chapter

- What practices of great places to work would you like to apply in your organization?

- Which of these could you begin to apply right now on your team?

- What resources or approval do you need for other efforts: for example, money for training and strengths assessments, support from upper management to implement new organizational practices, employee engagement surveys and analysis, and so on?

- Refer to the Roadmap to Hiring shown in this chapter. Consult with others in your organization who are involved in hiring, especially your boss and human resources manager, to develop a checklist that covers the steps you need to follow for hiring.

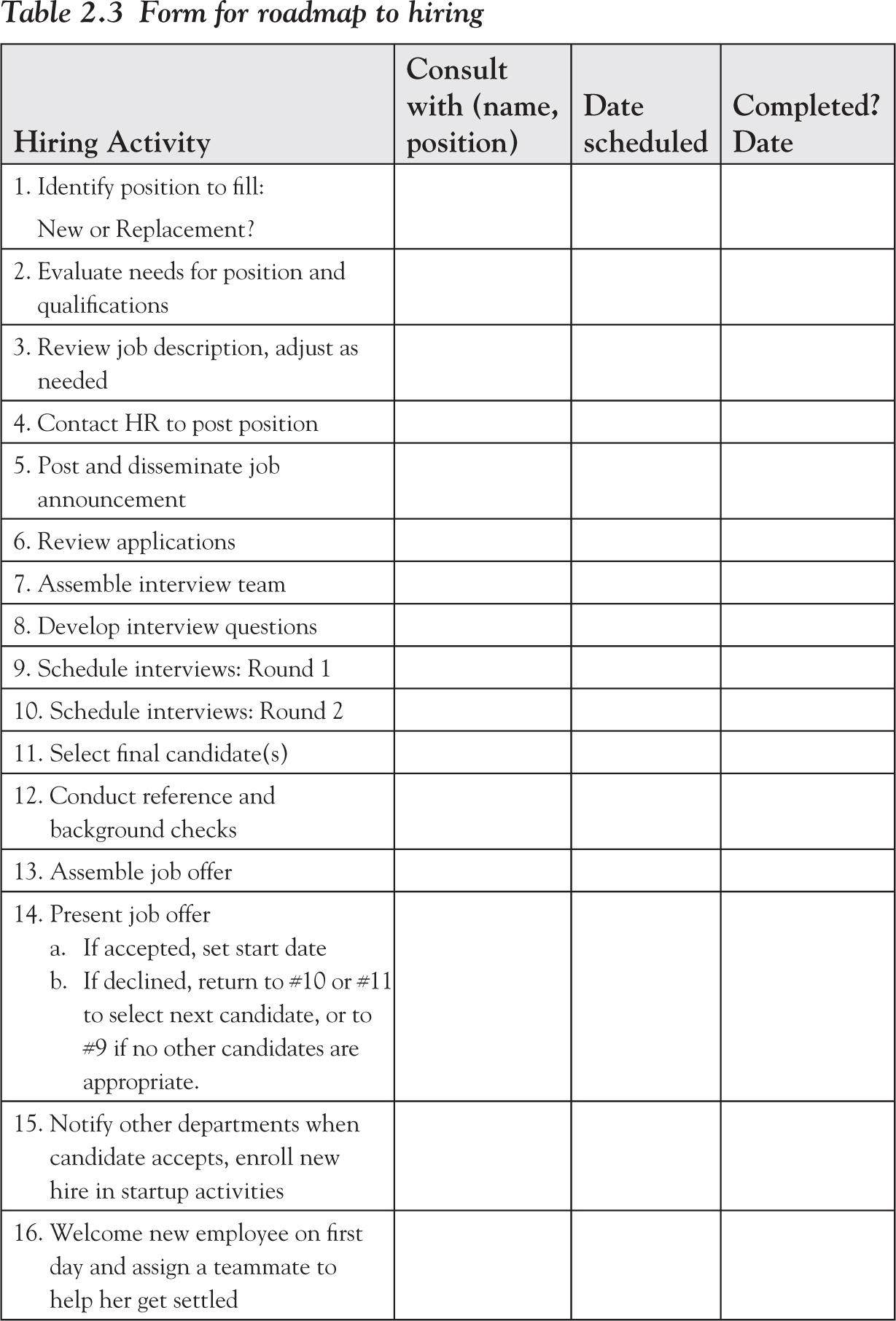

You may start with the form provided in Table 2.3 and add to or modify it for what is needed in your organization. Then, refer to it when you need to fill positions.

- What qualities do you need in all the people you hire, regardless of the position or credentials? Consider communication styles, attitudes, preferences, and other important things that impact their success in working with others in the organization, the patients your organization serves, their ability to get work done effectively, and so forth.

- After candidates are screened for meeting the credentials and experience required in the position, what behavioral interview questions will you ask?

Check that each question is important and relevant for the job at hand and does not discriminate unfairly against any protected groups or individuals.

- For specific jobs on your team, what other specific behavioral interview questions would you ask or demonstration activities would you conduct for your selection?

- What onboarding and orientation activities are offered by your organization? What else do you need to do to welcome your new employees and get each of them off to a successful start?

- Draft a “word picture” with clear and specific descriptions of the performance expectations and behaviors for someone working in a job on your team. Think of specific things you have seen people do that would make it clear what behaviors you would like a new employee to eliminate or emulate. For more on “word pictures,” see Volume I, Chapter 2.

- How could you assess and leverage your strengths and those of your team members to boost your team’s effectiveness?

- Does your organization already use any formal assessment tools of strengths or preferences in communications or work styles?

- Are there other tools or approaches you would like to try? Consider those mentioned in this chapter or conduct your own online searches of what is available, including some free online tools.

- What have you observed about your employees and the different things they each seem to gravitate toward using naturally and doing well?

- What projects or activities can you identify that would benefit from combining the complementary strengths of some of your team members to cover a comprehensive set of skills needed for overall success?