Enhancing Your Relationships at Work: Managing Communication, Feedback, and Conflict

Reflecting on Related Topics in Volume I

Your success as a manager requires that you build positive relationships. In Volume I of this series, our chapter on “Managing Up, Down, and All Around!” examined the essential relationships you need to establish with the people who report to you and with your boss whom you report to. We also looked at ways to connect with others in your organization to help you gain comfort in reaching out and building important relationship foundations. These topics helped build your awareness and skills for managing up, down, and all around the organization you work in.

Chapter Overview

Now it is time to enhance your relationships and work through some more advanced skills. It is natural that the various people you work with have different perspectives, so you can expect disagreements to arise. In this chapter, we extend your skills and effectiveness in communicating, giving and receiving feedback, and handling conflict. You will gain wider perspective and more experience as you practice building relationships and strengthening them all around you at work!

- Reflecting on related topics in Volume I

- Communication guidelines

- Giving and getting feedback

- Conflict in work relationships

- Chapter summary and key points

- Learning activities for this chapter

Communication Guidelines

Take initiative for communicating with others. This helps you build positive relationships, shows your loyalty to those you work with, demonstrates your capabilities for managing proactively, and often leads to better solutions and results.

Listening to Build Understanding and Open Dialogue

Stephen Covey advises, “Seek first to understand, then to be understood.”1 Covey recommends listening with empathy to fully and deeply understand another person, the way she feels and sees the world. Good listening builds positive relationships and helps us avoid jumping to conclusions.

Gene Dankbar of Mayo Clinic heightened his skills by taking classes in improvisational comedy, where there is practice in open communication by accepting and building on the ideas of others.2 With the approach known as, “Yes, And,” people learn to improvise by agreeing with the previous statement by someone else (with “Yes”), then building on that idea with something new (linking it with “And”). This promotes the flow of creativity and helps teams create more ideas, rather than shutting down contributions with a response such as “No, But.”3 When we say things like, “No, that won’t work here,” or, “But we already tried that and it didn’t work,” we communicate our resistance to other people’s ideas. Instead, try building your alignment with others by communicating your agreement or acknowledgement that their ideas have merit, and then add what you think could enhance it.

ABCs of Dialogue with Agree, Build, and Compare

An option for building dialogue with others is the “ABC” approach of Patterson et al. (2012) to Agree, Build, and Compare.

Start with Agreement

Look for and start with the points of Agreement. If you completely agree with where another person is going, say so and move on.

Agree and Build

If you disagree with some of the points, then Agree and Build. Similar to the “Yes, And” approach, you could say, “Absolutely. In addition, I noticed that . . . ” to add the pieces that are important to you and missing from his position.

Compare

Then, rather than suggesting the other person is wrong, you could suggest where you differ by moving to Compare to describe how you see things differently and “invite the other person to help you compare it with his or her experience. Work together to explore and explain the differences.” This approach can help you avoid turning differences into arguments that interfere with healthy relationships and good results.4

Here are some illustrations of how this could work.

Example 1

- Start with Agreement: “Absolutely, the new automated shift scheduling system made it much easier to plan for coverage over the holidays.”

- Continue to Build: “In addition, I saw there were still some last-minute schedule adjustments.”

- Next, Compare: “Did you see that, too? What do you think we could do to build some backup staffing plans now to cover unexpected changes quickly without disrupting the affected staff members?”

- Start with Agreement: “It sounds like our new on-site pharmacy is convenient for our patients and they report they get quick refills and good customer service.”

- Continue to Build: “And the nurses on my team tell me they aren’t getting timely information when something changes.”

- Next, Compare: “Do you know how the pharmacists on your team handle these changes and if they’ve had any problems communicating with nurses?”

As you listen attentively, you can ask questions that help you understand other people’s perspectives and priorities as you build alignment with them. It goes a long way toward preventing some uncomfortable conflict, and can be useful in working constructively with it when it inevitably emerges. We consider conflict more deeply in the final section of this chapter.

“Be Mindful of the Weight Your Words Carry”

This advice from Chris Radigan, LCSW, considers how our words can set the tone for people’s reactions and acceptance of us and our plans. It is important to remember that different people interpret words differently, especially with e-mail and the interpreted tone of requests and questions, which might differ from what you intended. Some things are best communicated in person; it is helpful to explain changes, why they are happening, and to ask for feedback. When Chris was a new manager, this approach helped establish trust with his staff to enlist the buy-in and support of his team members.5

Written Communications

If you do communicate via e-mail or written memos and reports, summarize succinctly in the subject or opening words the purpose of your communication and what, if any, action is needed from your boss or others. This helps bosses (and others in your communication loop) manage the information overload coming their way in many organizations, and to understand clearly and appreciate the good work you are doing. Imagine how helpful this can be for you if your boss’s boss hears of a problem and asks your boss about it and your boss can confidently respond about the constructive and proactive activities you are already planning and leading.

Be Alert to Communication Omissions

Communicate with your peers and others in the organization about changes and activities that impact their work or lie within their areas of responsibility. Make sure you never make commitments to others or communicate decisions that were someone else’s responsibility to make or approve!

Have you ever been in a situation where you found out something was decided or happening, and you did not know anything about it, even though it was something you had the authority to approve, veto, or reshape? Imagine how you would feel in your personal or family life if you were told you were going to be cooking dinner for your large extended family, whose members have a long list of dietary requirements and participants, you would never have agreed to do it, and perhaps you do not get along with that branch of the family!

Or someone in your household or neighborhood informed you that you would be picking up all the local soccer team members after their practice, on the same afternoon you had committed to facilitating a training session for an organization you lead. Or what about those friends of yours, back in high school, who you discovered were planning a party at your house the weekend your parents were going away? It is lucky that you found out about it and curtailed that one before having to explain to your parents why there was something different about the house when they returned!

Things like this happen at work, too. Maybe someone who reports to you executes a plan that should have had your support or approval but they failed to include you in the planning and communications. Suppose that plan or decision interferes with other activities in the organization, alienated your colleagues, and required you to intervene to fix the damage. Did that make you want to support the activity or decision that was dropped onto you, or the person who instigated the situation? Do not be that person to your boss or others!

Situations like these often happen when people assume that others support their plans, but they do not take the time to check or have direct conversations with those who need to be involved. Being intentional in our communications cultivates more productive flows of information and mutually supportive relationships.

Healthy Communication

You may hear people referring to communication and power issues as merely “office politics” and not to be taken seriously. They may be confusing healthy awareness and communication with unhealthy indirect communication and gossip about other people who are not present, which, indeed, should be avoided. As career expert Dale Dauten (2011) explains bluntly in a column to a reader who wrote in for advice,

I know there are people reading your remarks and getting huffy about “company politics.” One of the dumbest things I hear smart people say is, “I do good work, and that should be enough—I refuse to play politics.” Corporate politics is merely the art of getting things done by communicating with people in the most effective way, and that means using language that they understand and respond to. If you declare yourself to be “above office politics,” then you have declared you don’t really care about being effective and don’t deserve to be promoted.6

You, in contrast, have already demonstrated through your qualifications and successful work that you do deserve to be promoted, and now you are a manager! Keep in mind that while the label of politics may carry negative connotations, influencing others is a very real and necessary component of leading and managing at work.

Practicing clear communication skills as we have discussed here will help you build the working relationships around you that help you increase your effectiveness in leading your team and influencing others to collaborate with you and support your goals. And, in addition to what you say and how you say it, it is important to consider channels of communication and making sure you include the right people—those who have a need to know, the authority to decide, or the expertise to implement decisions effectively.

Including Others: Who Else Needs to Know?

At the Mental Health Center of Denver, we found it helpful to consider “Who Else Needs to Know?” People quickly adopted this as WENK soon after it was introduced to the organization by Mary Peelen, Director of Health Information Management Systems, from her earlier experience in a home health organization. The approach helped prevent problems by making sure all relevant information and requirements were identified and considered ahead of time. This approach improved teamwork, collaboration, communication, and project implementation throughout the organization.

It was especially helpful when we were awarded funding through grants to start new clinical operations that required new tracking codes, clinical outcomes analysis, service delivery, quality monitoring, and reporting across multiple functions and departments. WENK can be implemented with a simple checklist and commitment throughout the organization to follow it. The example in Table 1.1 is about a new clinic funded by a community foundation to increase access to health care treatment for low-income preschool children. You could develop a checklist or adapt Table 1.1 for use in your organization.

Breaking Down Silos and Barriers

Several interview participants talked about “silos” and the importance of breaking them down. Picture silos as distinct towers or receptacles holding resources that remain separate and do not get mixed with those from other silos. Breaking down silos in organizations means working cooperatively across functional areas to share efforts and pool information and other resources for the greater good of the organization. It requires that we raise our vision beyond the confines of our individual goals and team responsibilities and consider the broader mission and vision of our organization. Breaking down barriers can start with communication and appreciation for the contributions of other people, especially in functional areas outside your own team or department. We saw in the preceding text how we could involve and include others in implementing changes by actively considering who else needs to know and inviting them to participate in planning.

Many people who were interviewed for this series of books mentioned the importance of building relationships with people in other departments or functions in their organizations, especially in administrative areas such as human resources and accounting where their guidance and expertise is valuable and often necessary. We will offer more specific recommendations in the later chapters focused on those functions.

Example 1: Working Across Internal Departments

When I assumed responsibility for a team that produced reports of services that were paid for by county funds, it appeared that we were responding to frequent ad hoc requests for information. In the past, clinical managers had been responsible for handling the reports themselves, without a solid system of scheduling and technology to assist them. Because the responsibilities were distributed among so many different people, we lacked a coordinated schedule for when the reports were due and expected by our external customers.

Then I discovered that our contracts manager in the Finance department had recently acquired a contract tracking system where due dates were visible and responsibilities for reporting and delivering could be assigned and communicated to the right people. Now we had the tools, and even the analytical team members available, to handle this efficiently, which alleviated a reporting burden from the clinical managers who had been scrambling to work these administrative reporting tasks into their other responsibilities. We coordinated the right resources to establish a predictable schedule for when the reports were due and expected by our external contacts at the county.

My analytical team members knew ahead of time what they were responsible for and could manage their work schedules and due dates. They began to communicate actively with external report recipients to clarify expectations and negotiate what they could deliver if there were special requests for customized reports. By planning, organizing, and communicating across teams and departments, we built more effective workflows and more satisfying and productive relationships with our internal colleagues and our external customers.

Example 2: Cultivating External Relationships

“Relationships and sponsorships matter a lot. I was loyal to the people I built relationships with. It’s important to be protective of them.” Jesús Sanchez, PhD, built and protected his external relationships throughout his career in clinical, management, and administrative roles. He fostered relationships with other units and organizations, and knew it was important to get along with the people whom he valued. He found that his relationships were helpful in getting the job done.

For example, when he was an outpatient clinic manager, his positive and mutually helpful relationships with his counterparts in hospitals helped the patients they both served to access the right levels of care promptly and smoothly. He removed barriers for his team members by working with his hospital counterparts to obtain needed resources such as parking access so his clinicians could more easily do their work when they needed to visit the hospital to coordinate with staff there. He valued the help he got from his external working partners and preserved trust and integrity in these relationships by making sure commitments he made to them were upheld by his organization.7 This required him to communicate actively within his organization about the importance of these external partners. He enlisted the support of others “up” and “all around” in his organization whose help he needed to fulfill commitments and support the people who reported to him.

Example 3: Recognizing Cross-Functional Collaboration

Kelly Phillips-Henry, CEO of Mental Health Partners, supported and communicated successes throughout her entire organization. She explained that in organizations that provide clinical services, administrative contributions might not always be as visible or celebrated as direct clinical activity, yet it is important for all staff members to recognize how the activities throughout all of the organization have value and support the organization’s work and mission.8 She recognized efforts from all parts of the organization, including the fee collection project led by an administrative director, by sending an e-mail message to all staff to praise the efforts of the leaders and everyone who had participated throughout the organization.9

Giving and Getting Feedback

Feedback takes many forms. When it conveys recognition or praise, it can encourage more of a desired kind of behavior. On the other hand, it can let people know when they need to correct or change something. Let us start by looking at how you can give feedback positively.

Providing Positive Feedback

It is important that you offer positive feedback to the people who work with you. This helps you build positive relationships by showing others that you notice and appreciate their contributions and what they do well. This demonstrates your goodwill toward them and establishes mutual support and alliance. It is especially important that you provide positive feedback to the people who report to you because it reinforces to them that they are on the right path in doing what you want them to do. This enhances their performance by making it likely that they will continue to do the right things to achieve the goals you desire.

Motivation author Barbara Fielder (1996) suggests using a systematic approach to track and ensure that you are giving positive feedback regularly by putting 10 coins in a pocket to remind you to give someone positive feedback, praise, or recognition. Each time you do it, move one coin to the other pocket.10 I heard of a manager who was told he did not give enough recognition to those who reported to him. He established a daily goal to get all 10 coins moved to the other pocket by the end of the day. People noticed a difference and felt more motivated in their work with him.

A colleague of mine, Bill Milnor at the Mental Health Center of

Denver, was intentional in developing the habit of noticing what others were doing well and deliberately praising them. This earned him the reputation of being a supportive mentor to many emerging leaders who developed their skills and grew their managerial effectiveness through his feedback and guidance. This illustrates Ken Blanchard’s and Spencer Johnson’s recommendation for you to catch people “doing something right” and offer immediate and specific praise and encouragement, along with your positive feelings about their progress and contributions to the organization.11 Regardless of your method, the key point is to notice the positive things people do and express appreciation. This strengthens the performance of others along with your relationships with them.

For Corrective Feedback, Start with Permission

A good way to set the stage for giving and receiving feedback is to apply Harley’s (2013) recommendation that you ask permission at the start of your working relationships. Ask people to be honest, encourage them to tell you if they notice something you need to change or improve, and ask for their permission for you to tell them if you see something getting in the way of their success. Do not assume you are doing a good job because no one has told you that you are not. You need to take control, verify others’ perceptions, and let them know that you welcome their feedback. This is crucial to your success.12 Her approach is effective with your boss, peers, and those who report to you. Because of your positional power as their manager, the people you supervise may be reluctant to tell you the truth, but understanding their perceptions helps you know what you should adjust or continue doing to be as effective as possible.

I noticed that my colleague, Vicki Rodgers at Mental Health Partners, was straightforward and effective in using this approach. She explained that she had learned to do this in earlier settings and had talked with someone she had reported to about how to ask for feedback. She was comfortable asking people she worked with, “If you’re ever uncomfortable with me or something I’m doing, feel welcome to call me on it.” This allowed permission for someone who reported to her to tell her directly when they were in supervision that the person felt that Vicki, her supervisor, was distracted by other things, “I need your undivided attention.” This prompted Vicki to refocus her attention on her supervisee, which improved their interaction at that moment and in the future.13

Open Up to Receiving Feedback

“The physics are clear: close down and get worse. Or, open up and get better.” According to Henry Cloud (2013), leaders are hungry for feedback. Getting feedback means opening up to take in new information, beyond your own perspective, about your performance and its effectiveness, along with suggestions for improving it. He advises that you look outside of yourself and even go outside your organization, as many of the managers interviewed for this book did to learn from others with different experience and other points of view. This can help you open up and be honest about your difficulties and vulnerabilities with independent and unbiased external colleagues with whom you can be mutually supportive in encouraging each other’s growth and development. Cloud recommends, “Get coaching, join a leadership group or forum, avail yourself of continuing education, attend a leadership conference, and so forth.”14

Ask with “Start, Stop, Continue”

A simple and effective framework for getting feedback about your performance is the “Start, Stop, and Continue” approach. It can be posed as a question to others as, “From what you experience in working with me, what should I start, stop, and continue to do?”

I was reminded a few weeks ago that it also can be used to reinforce learning and assess progress of yourself or others in working toward goals. Jean Rosmarin, PhD, my co-facilitator for a Mental Health First Aid training class we conducted for our county sheriff’s department, asked participants at the end of the class, “From what we covered today in class, what will you start, stop, or continue to do to practice good self-care?” This helped participants consider what they had learned and express an intention to practice it, and it provided feedback to us as facilitators about what they took away from the training experience. It helped us gauge how effectively we had covered some of the topics, and helped us understand some differing perspectives among our audience.

Conflict in Work Relationships

“Don’t take it personally if others don’t agree. Explain it and move forward.”15 This advice from Jeff Zayach, MS, Executive Director of Boulder County Public Health, reminds us that you must learn to be comfortable managing people who have different perspectives and be able to move forward even if not everyone agrees with your decisions. This requires recognizing conflict when it happens, responding to it promptly, and resolving it with your words and actions.

Why and When Conflict Occurs

Conflict is part of life. It reflects different perspectives, preferences, and priorities. People may disagree in their values and beliefs. They may have different interpretations of facts and other factors. It emerges with those who report to you, coworkers, and those at higher levels. Often people just want and believe different things. It could appear when others react to you in your new management role and as you assert new authority as you work with people with different perspectives, goals, and approaches. Sometimes people violate expected behaviors and communication channels, perhaps unintentionally. Understanding and setting expectations can help you avoid initiating unwanted conflict; see Volume I in this series for more help with this.16

Conflict was mentioned by a number of our interviewees who had been selected for a new managerial role ahead of others who had been with the organization longer and had sought the promotion to a management position like the one you have now. Many said they had felt hesitant, uncomfortable, or unsure what to say or do to smooth things over and get people and relationships working well.

In some cases, the new manager’s boss was helpful in supporting the new manager and not allowing others to ignore the new manager’s positional authority and exclude her from decision-making and communication channels. In other cases, the new manager’s boss was uncomfortable and avoided direct communications or actions that could ease the disruption of hurt feelings and nonproductive behavior of those who had not been chosen. If your boss is not actively reinforcing to others your new authority, you could try asking him directly for such support. However, if your boss is not willing or able to do this for you, you need to do it yourself.

Conflict can be healthy when it occurs in an open and respectful environment where productive discussion can reveal new understanding between people who work together, or open up options and alternatives that lead to better decisions. However, it can be unhealthy and destructive when it remains unaddressed and festers bad feelings, people become entrenched in competing positions, believe they must exert power and control over others, or view discussions as win-or-lose games in which they must be the winner.

Although it can feel threatening and tense, there are healthy ways we can work with conflict, which we should embrace rather than fear. You have already seen techniques in the preceding text, including “Agree, Build, and Compare” from Patterson et al. (2012) for listening and aligning with others to handle “crucial conversations.”17 Let us look at some additional ways to manage these crucial turning points and guide them to productive resolution.

Embracing Conflict

“Conflict can be welcome in helping to elicit and develop new ideas,” as Jackie Attlesey-Pries, MN, RN, observed.18 Stephen Robbins (2013) explains that conflict can be constructive when it improves the quality of decisions by allowing various points of view to be heard, especially those that are unusual or held by the minority. This can help a group consider alternatives, challenge the status quo, and create new ideas.

Groups composed of members with different interests tend to produce higher-quality solutions to a variety of problems than do homogeneous groups . . . Evidence demonstrates that cultural diversity among group and organization members can increase creativity, improve the quality of decisions, and facilitate change by enhancing member flexibility.19

“Now, Hear This with Love . . . ”

People really enjoy working with Fred Michel, MD, a former teammate of mine, who recommends that we engage in conflict rather than avoid it. He suggests some approaches he uses successfully, such as a cue to ease into it without offense. For example, in team meetings, we recognized his opening of, “Now, hear this with love . . . ” and accepted willingly what followed because we trusted his integrity as he respectfully offered his opposing views or criticism of how things were working.

In working with others such as the medical team members Dr. Michel manages, he sometimes starts with, “Good, bad, right, or wrong . . . ” to set the stage for the clear direction about “this is what we need to do.” He suggests aligning with others by starting with an apology to recognize something difficult or uncomfortable in their world before making a request. For example, consider starting with, “I’m sorry the weather is so cold when you had to come out here today for our team meeting.”20 This could be the preface for a request such as, “Now I need to ask for everyone’s cooperation in making sure our documentation is solid for the coming Medicare audit.”

Adapting Cues for You to Use

How might you apply these suggestions in working through conflict situations or challenging requests you need to communicate? You could adapt the cues to wording that is more natural for you. Here are a few examples for illustration:

- “Now, I know this might sound far-fetched, but I wonder what would happen if we applied some tools from our technology team to remind ourselves to tell patients about our new clinic hours.”

- “I’m listening to the ideas our team came up with, and I have to admit, I’m confused about what the goal is. Could someone explain how this helps our patients?”

- “It’s difficult to comply with these new safety regulations, and I wouldn’t ask this if I thought we had a choice. Now, can we figure out how we’re going to put these in place by the federal deadline?”

- “I’m sorry we’re all struggling with this new electronic health record. These transitions always seem to be difficult, and we have to do it because the old system is shutting down at the end of the month. Shawn, I saw you working with our vendor to pick up some helpful shortcuts. Are there some things the rest of us might learn to make it easier?”

Conversation, not Confrontation

“Start a conversation, not a confrontation,” Mark Murphy (2017) advises. He suggests asking the other person if she has time to talk with you, letting her know the topic, offering a few possible times and asking which would be convenient for her. This approach can be received by the other as more collaborative and less confrontational than a direct statement that you have a problem and want to talk to her about it.21

Imagine that it appears to you that a colleague has proceeded on his own in resolving a problem without considering your team’s responsibilities and the work your care team members already have in progress. Instead of expressing to him your feelings of frustration, you might approach him with a question to request time to talk about the situation, like this.

“Marc, do you have some time to talk with me about our response to the Denton family’s complaint about their mother’s discharge? I’d like to coordinate with you on our communications.” If the other person agrees to talk, you can offer some times, such as, “Would you like to do it now or would it be better after lunch?”

If the other person wants to know more about why you want to talk, you might offer a brief, objective explanation, such as, “I want to make sure we’re in alignment on who’s handling which parts of the discharge process so we’re communicating clearly with the family and prevent confusion.” This opens the door to a nonjudgmental conversation that illuminates the activities that are occurring and who is handling them, which can lead to constructive and collaborative consideration of how things are working and what might be adjusted.

With an approach like this, it is less likely the person will refuse to talk with you than if you had approached him more confrontationally, but if he does refuse, then Murphy recommends you respond with a question, such as “May I ask why?” to get more information about his perceptions.

Discomfort with Conflict

As Stone, Patton, and Heen (1999) point out, feelings matter, and they are often at the heart of difficult conversations. Unexpressed feelings make it difficult to listen to others, and take a toll on our self-esteem and relationships. People may dismiss their feelings as unimportant or unjustified, but your feelings are as important as the other person’s.22 As many experienced managers have shared, when they delayed talking to people about their concerns, they prolonged stress and discomfort in the relationships that they could have avoided by speaking up sooner.

For example, a manager admitted that he delayed talking to someone who reported to him because he felt uncomfortable after she had overstepped her bounds by communicating to others a decision she made on his behalf without talking to him about it ahead of time. The manager had mixed feelings about the decision itself, and thought it might actually help the team function better, but he felt unpleasantly surprised and that his decision-making authority had been usurped. He avoided talking to the employee until several months later when he was annoyed with her about a different situation. When he finally blurted out his dissatisfaction about the earlier situation, she was astounded, and declared, “Why didn’t you just tell me? I don’t want my boss to be mad at me for all this time!”

Why do we avoid these conversations? It may be a fear of offending or alienating the person, or opening up issues that you would rather avoid, such as your own inexperience or discomfort being in charge.

As Cloud (2010) points out, it is important to distinguish between the temporary “hurt” that can be a necessary part of providing uncomfortable feedback, and the longer-term “harm” to the organization caused by allowing performance problems to persist.23

The example illustrates additional principles to keep in mind as you begin to manage and lead others. Keep in mind that most employees really want to do a good job,24 and they want to please you as their boss.25 Think about feedback as an opportunity to coach employees so they can grow and develop. When you withhold your timely feedback, they are denied the information and opportunity they need to correct off-course behaviors and improve performance. They may unknowingly repeat things that hinder their effectiveness and annoy you, which detracts from overall team performance that you are responsible for.

Think about how you claim your authority and leadership responsibilities as boundaries, in terms of what you expect, will accept and tolerate, along with limits that you will protect. Henry Cloud (2013) explains how this helps to position you to be an effective leader, or in his words, to be “ridiculously in charge”26 by establishing and reinforcing your position as the manager and leader of your team.

Keep in mind that situations that trigger conflict can arise among people at different levels of hierarchy. It could be a peer-level colleague who says something in a meeting that you feel is unjustifiably critical toward you or your team. Or it might even be your boss who seems overly involved in making decisions about responsibilities she had delegated to you. In any case, do not delay. Open the conversation to share your observations, ask for feedback, and create understanding to prevent lingering problems and discomfort.

Handle Conflict Promptly

Be clear, direct, and prompt in addressing concerns, to prevent problems from lingering. If you believe that someone has crossed a line and behaved inappropriately in her role, or that his performance is not meeting standards and requirements of his job, or you have some team members who violate other expectations you hold for them, it is best for you to deal with such situations promptly. This helps you avoid more difficult confrontations later, when they have assumed that you approved of their behavior or performance because you never told them otherwise!

Initiate Needed Difficult Conversations

You could initiate these discussions by calmly stating the facts along with what you noticed, and asking for the other person’s feedback. Mark Murphy (2017) recommends a truth-based approach based on the facts of the situation.27 Let’s apply this approach to our example of the manager whose employee had communicated a decision without clearing it with him.

Jane, I heard from several team members that you sent a memo announcing that I had decided that everyone could manage their own schedules and plan time off without prior approval from me as long as they found coverage for time when they planned to be away. I’m concerned because I was not aware that you were planning to announce a change, which I’m responsible for approving, about the way our team operates. Now several team members are confused and have asked for time in our team meeting agenda to clarify the procedure.

These are the facts as the manager, Sam, is aware of them. Then he opens up the discussion by asking for the employee’s feedback.

“Could we talk about what happened and how we could work together to plan and communicate effectively?” It is possible that the employee believes there are other relevant facts and perspectives to consider. For example,

Sam, you said you spend too much time approving schedule changes. And you said you could use my help in finding ways to run things more efficiently. Other teams I’ve worked with operate this way and everyone likes it. I wasn’t trying to question your authority, I was trying to use my experience to help you and the team.

Distinguish Blame from Contribution

Stone, Patton, and Heen (1999) recommend that you distinguish blame from contribution. Blame is about judging, and looks backwards, in contrast with contribution, which is about understanding and looking forward. Contribution is joint, interactive, and encourages learning and change.28

Jane had feedback for Sam about their working relationship and how to make it more positive and productive, and what she needed from him as the team’s manager. Let us consider how Sam might have contributed to the problem if he told Jane he wanted more help from her, but he was unavailable to talk to her about her suggestions. Suppose that he had denied Jane’s requests to meet with him and then overlooked an e-mail message Jane had sent him with a suggested plan, and Jane erroneously interpreted Sam’s lack of response as implicit support for her plan.

Rather than looking backwards and blaming Jane for undermining his leadership and decision-making authority, Sam could look forward and talk to Jane about how she could offer her suggestions in helpful ways that he could understand clearly and respond to promptly. Such a conversation allows Sam to remind Jane of his willingness to listen to suggestions, and when and how to approach him with them, along with his expectations for approving decisions.

Be Respectful toward the Other Person and Other Perspectives

Sam demonstrated openness and respect for Jane and her perspective when he opened the conversation for her feedback. The dialogue allowed Jane to contribute her ideas, build more trust with Sam, and increase Sam’s comfort in delegating more responsibilities to her and other team members. This demonstrates that with openness to addressing conflict constructively, Sam and Jane each could benefit from the advice and encouragement found in Harley (2013) about “how to say anything to anyone,”29 especially when a team member needs to clear the air with a boss!

Consider Role-Related Power and Authority Dynamics

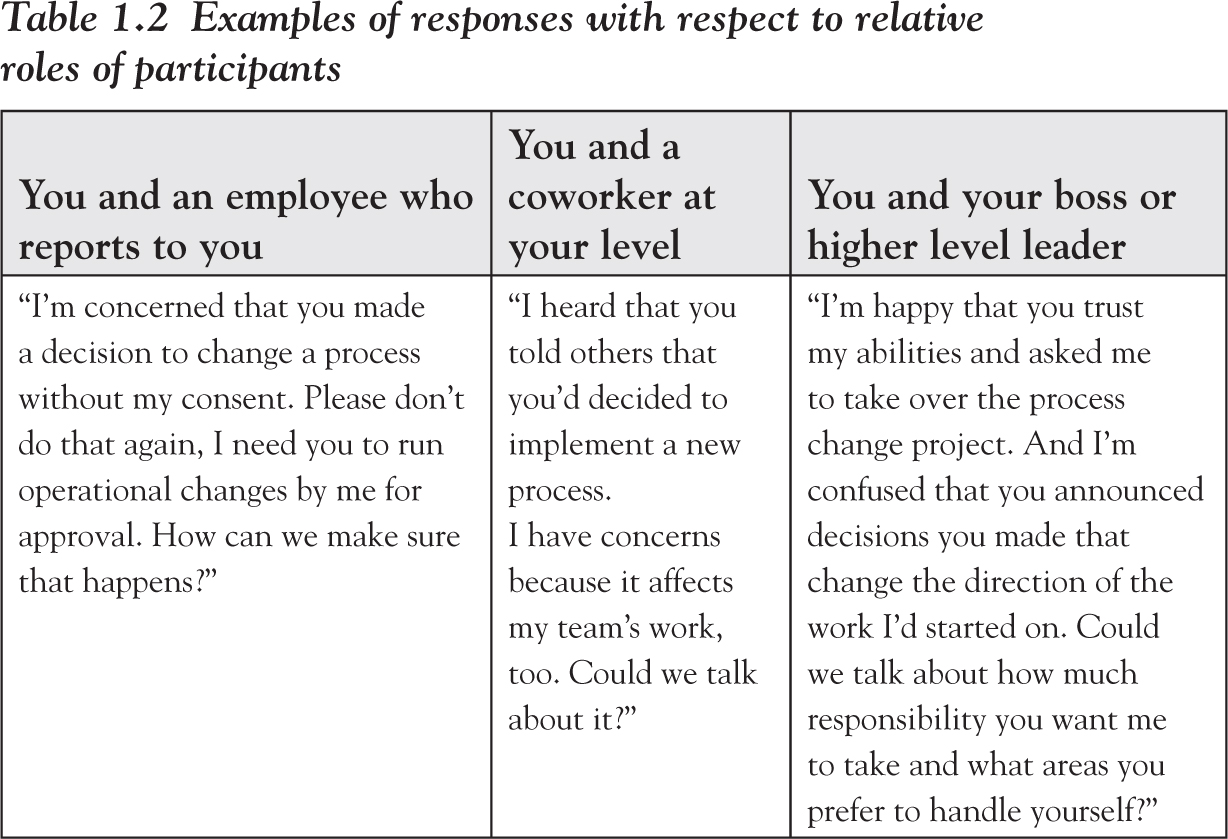

Remember, conflicts can and do occur up, down, and all around. The next time, it could be your boss who neglects to include you in needed communication or decision making that encroaches on your responsibility and affects your team. Or it may be a coworker who seems to push for her goals to the detriment of yours. Be respectful and straightforward to initiate conversation, practice listening, and work toward understanding and alignment.

Always be mindful of your position in the organizational hierarchy and be aware of who reports to whom. You do have power in your managerial role that gives you the authority to make many decisions and set direction for those who report to you.30 In turn, your boss has this authority over you. Adjust your approaches and conversations accordingly. You can be more directive with your employees than you can be with your boss.

Consider appropriate approaches for you in your position relative to the other person’s. What should your stance be along a continuum from giving direction from a role of authority, to collaborating equally, to requesting direction from someone who has authority over you?

For example, the other person made a decision, without your input, that affects your area of responsibility. Some more examples of responses with respect to relative roles of participants are provided in Table 1.2.

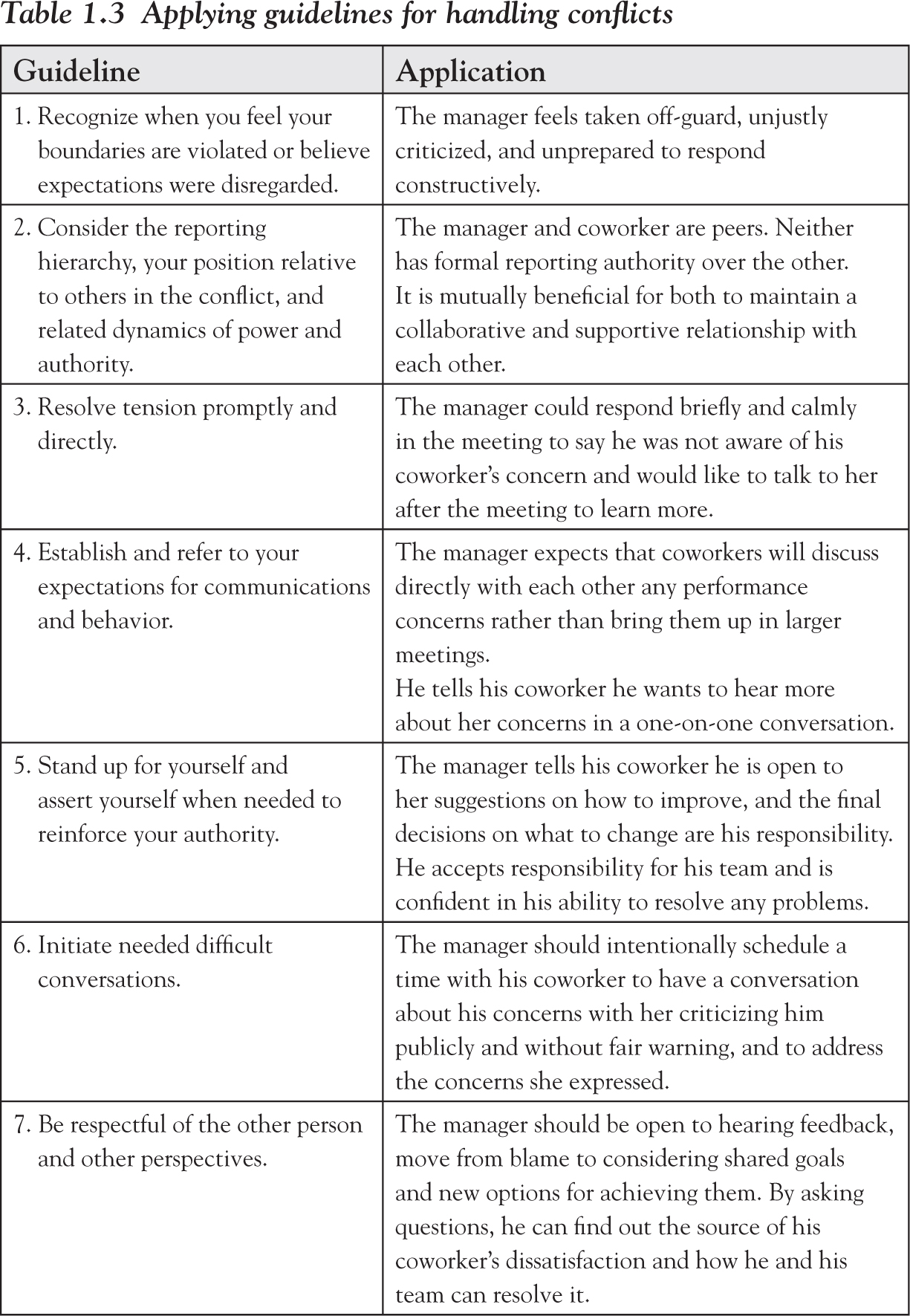

Guidelines for Handling Conflicts

These guidelines (Table 1.3) summarize approaches we have covered for handling conflict. We apply them to an example situation of a manager who was unhappy with a coworker’s criticism of his team, which was discussed in a larger meeting with other coworkers and the senior manager they all report to.

Chapter Summary and Key Points

In this chapter, we offered communication guidelines and recognized the ways feedback and conflict are important elements of the workplace. We suggested ways for you to give and receive feedback in constructive ways that foster relationships and help people work together collaboratively. We examined conflicts and offered guidelines for handling them in ways that build positive relationships and get work done effectively.

Key Points:

- In communicating, listen and seek to understand others. Consider your words and choose them to build alignment.

- Be mindful of your words and tone in your spoken and written communications. Be clear and direct to ensure others understand accurately what you intend to communicate.

- When you are involved in change, consider who else needs to know and include needed people early in planning activities and decisions. Use a checklist for who else needs to know and be alert to avoid leaving anyone out.

- Sharing information and pooling resources among different parts of the organization can break down silos to foster cooperation that helps get things done more easily.

- Positive feedback is important for showing appreciation and reinforcing positive actions that you want your team members to continue.

- Ask for permission to give feedback to others and ask them to tell you if you need to change or improve something.

- To gain precise, targeted feedback, ask others what they suggest you start, stop, and continue to do.

- Conflict is inherent in the workplace because of the varying perspectives of different people. Learn to embrace conflict and manage it in healthy ways.

- Understand your own boundaries that you need others to respect. Recognize when others violate them, and respond promptly and appropriately to others whether they are up, down, or beside you in the organizational hierarchy.

- Be clear, prompt, and direct in handling conflict so that issues get resolved and relationships thrive.

- Use conversation, not confrontation, to initiate constructive resolution of disagreements.

- Recognize and respect the differences in positional power and authority of people in roles at various levels in relation to yours.

Learning Activities for This Chapter

- Think of a problem that needs to be solved in your organization, which requires cooperation between you and a peer. Consider what points you both agree on, where your perspectives differ, and how you might agree to work together to solve the problem. Plan a conversation you could have using the framework of Patterson et al. (2012) that we reviewed in this chapter to Agree, Build, and Compare.

- What projects or situations come up at work, which require careful consideration of “Who else needs to know?” Construct a table or checklist, like the example in Table 1.1, which would be helpful to use in your organization.

- List three things you have noticed people doing well on your team in the past few days.

- Write down what you could say to those people to give them specific positive feedback that recognizes their good work and encourages them to continue to build on it. Now, go deliver the feedback.

- Look for at least three more opportunities in the coming week to offer positive feedback to others who work with you.

- What will you say to others to encourage them to give you feedback about how well you are meeting their expectations and what you need to improve?

- In this chapter, we introduced a framework for getting feedback by asking others what they would like you to Start, Stop, and Continue doing. You can also apply this for self-assessment and goal-setting for your professional development. From what you saw in this chapter, what will you Start, Stop, and Continue doing to become more effective?

Here’s an example to get you started.

“I will

- Start scheduling regular meetings with my boss to review goals and get her feedback on my progress.

- Stop avoiding difficult conversations and believing that other people’s needs are more important than my own.

- Continue to attend monthly skill-building seminars offered by my professional society’s local chapter to build my skills in managing others.”

- Identify at least one work conflict or uncomfortable situation that you need to address. Imagine a conversation you could have to help resolve this and what you would say to get the conversation started.

- How would you approach the other person to start the conversation? Consider the other person’s role in the organizational hierarchy—in other words, are you peers at similar levels, or does one of you report to the other, or is one of you higher in the managerial hierarchy with more authority than the other? How do these relative positions of your role and the other person’s affect the way you approach the other person to start the conversation?

- Find an uninvolved person, not connected with the other person, who could help you practice this conversation by playing the role of the other person. What mentors or peers could help you with this?

- What feedback did you get from your mentor or peer-level buddy, or discover for yourself as you practiced, and what would you adjust in your approach to handling the conflict?

- Think of a situation at work where someone’s actions violated your expectations for how he should have behaved. Work through Table 1.3 to apply the guidelines for handling conflicts, and fill in your application of each guideline. Refer to Table 1.2 for examples to help you apply Guideline #2 to consider the reporting hierarchy, your position relative to others in the conflict, and related dynamics of power and authority.