Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- explain communication context;

- explain the power of leaders;

- explain organizational communication climate;

- discuss established levels of organizational culture;

- differentiate formal from informal communication networks.

Introduction

Context is the physical, social, and psychological environment where the communication interaction takes place. Imagine a 45-year-old manager paying a compliment to a 22-year-old administrative assistant, who has just been hired, on her wardrobe. He tells her, “You look very professional today and ideal for our company.” Much to the manager’s chagrin, the administrative assistant asks, in a rather scornful tone, “What are you looking at?” She is loud enough for others passing by to hear. The manager, feeling confused and embarrassed, immediately apologizes and tells the young woman, “I am looking at nothing more than your wardrobe,” he continues, “Have a good day, Ms. Jones.” In this hypothetical example, the physical environment is the hallway. The social environment is the organization’s culture and climate, where the manager is comfortable enough to pay a compliment to a young woman he barely knows without fear of accusation. Because the young woman was new to the company, she did not understand that she was receiving a compliment.

Communication Context

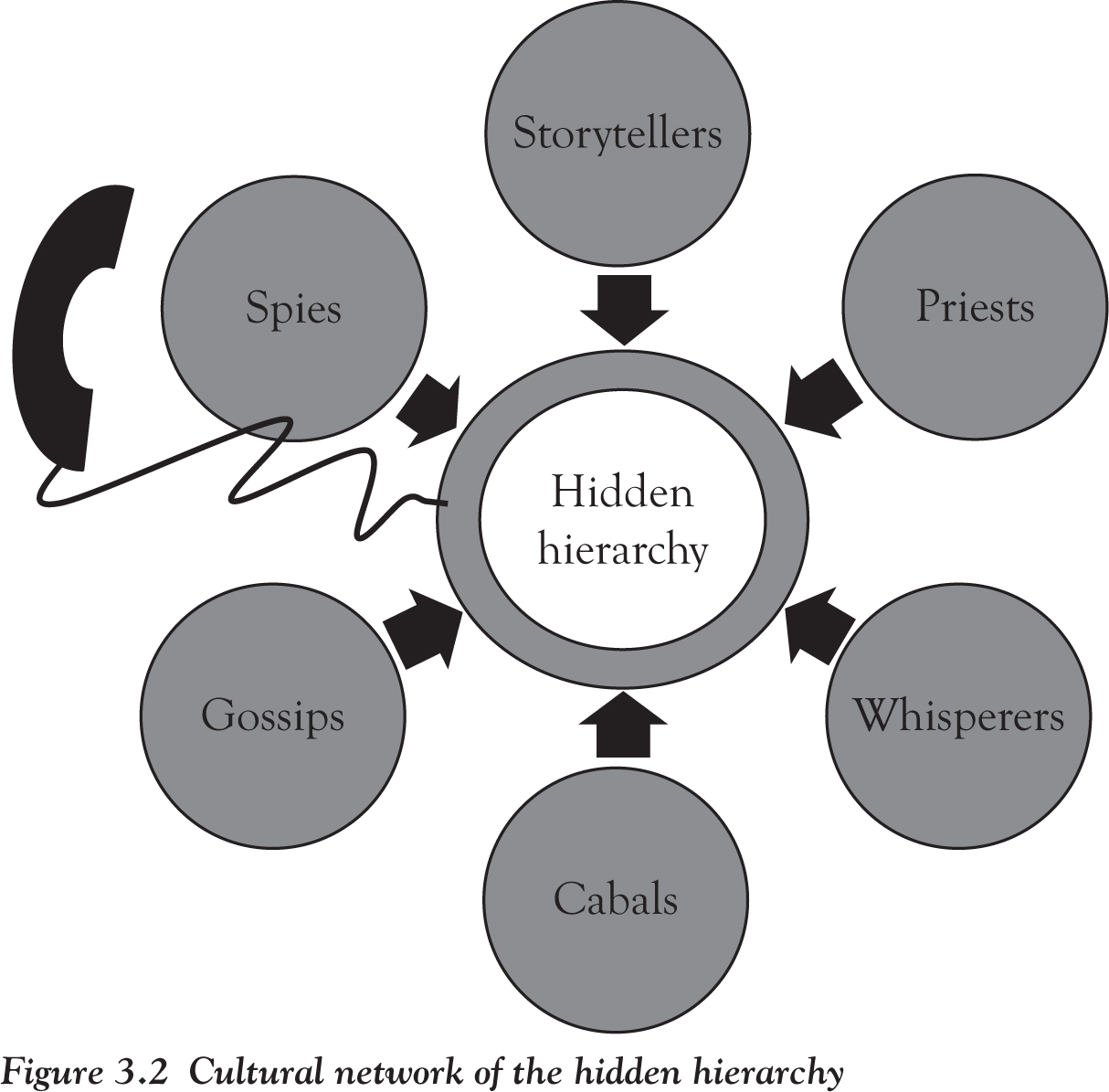

Understanding culture is essential to effective communication. Based on how an organization and its leaders view culture, behaviors can vary. Table 3.1 contains some well-established definitions of culture and corporate culture.

In the earlier example, the psychological environment exists individually, inside the minds of the manager and the administrative assistant. It is possible that the young woman harbors remnants of bad experiences. It is possible that she previously worked in an organization where sexual harassment existed in a climate of tolerance for such behavior. It is also possible the manager had just harassed the administrative assistant. Incidents of one individual harassing another under the veil of good intentions are not uncommon in business. Complimenting a woman’s wardrobe while looking at her chest the whole time could be the reason for a young woman to react to a compliment with a scornful rebuke.

In this chapter, we will consider the power of leaders, organizational communication climate (OCC), and culture. First, as a manager you will need to understand the dynamics of the power that different types of leaders have within the communication context. Second, you will need to understand the climate of the organization in which you work. Third, you need to be able to navigate the levels of organizational culture and understand that culture is both visible and invisible.

The discussion begins with brief definitions of leadership and leaders. We will then explore the five powers of leaders in context.

Power of Leaders

Leadership is a process to provide forward movement for the organization—visions for the future. Managerial leadership is a process used to influence employees to reach the common goals of the corporation. Reaching the firm’s goals is easier when managers lead and strive to achieve common goals for the good of all. An organization must have both managers and leaders to succeed, though they are not always one and the same. Leaders need to be able to listen and hear in order to influence employees. They need to be informed and ask others’ opinions about current situations and new ideas. Leaders influence others to reach common goals—mostly through their communication efforts. The five bases of influence that give leaders power are (1) referent power, (2) expert power, (3) legitimate power, (4) reward power, and (5) coercive power.

Referent Power

Referent power is based on the individual’s personality. Power can be used for bad or good reasons, and some immoral communicators have led people to terrible ends by abusing their referent power. This was the case with Jim Jones in 1978. A preacher with incredible influence over his congregation, he convinced his followers that the end of days was happening. More than 900 of his followers, either willingly or under duress, drank a punch laced with the highly lethal poison cyanide. That tragedy is now infamously known as the Jonestown Massacre. On the positive side, Warren Buffet can merely mention a stock as a personal like and people will flock to buy that stock. Oprah Winfrey can talk favorably about a book she has read, and overnight that book becomes a best seller. Many others have gained power based on their personal charisma or level of knowledge in a field or industry.

The Window into Practical Reality 3.1 exemplifies just how significant referent power and an attractive personality can be in the political arena.

Window into Practical Reality 3.1

The Unlikely Election of President Donald Trump—A Near Perfect Example of Referent Power and Rhetorical Skills

People in all walks of life and from every social class the world over, and especially those with the power over the media, predicted that Trump would never be president of the United States. Ironically, to their chagrin, the voting public made Donald John Trump president. He took the oath of office on January 20, 2017, with his hand on his family Bible and the Abraham Lincoln Bible, and became the 45th president of the United States of America.

There is nothing more interesting for people who study mass media and public discourse than to look at what occurred in the 2016 U.S. presidential election. The fact that Trump could defeat 16 established Republican candidates in the primaries and defeat a Democrat candidate, who seemed to have the mainstream media (MSM) clearly on her side, with his use of rhetoric and an appeal to nationalism has many scratching their heads in disbelief.

The verbal attacks on President Trump started long before his announcement that he would be running for president. In fact, it was the ridicule directed at him which seemed to transform his speaking style. His opponents introduced the very weapon that Trump used to defeat them. Because the MSM chose to air language that was historically viewed as vulgar and trite against Trump, they inadvertently set the rules for political discourse in the modern era. The media made ridicule and impoliteness fair game in airing grievances in the public arena. In other words, it seems President Trump’s tactics emerged from a 2011 White House correspondents’ dinner.

The comedic attacks on his intellectual abilities and character gave him tacit approval to use similar language against his opponents throughout the campaign for his presidency, including his daily Twitter posts. In 2011, the general consensus was that Donald Trump would never be president of the United States; it was said with certainty by many. At a White House correspondents’ dinner, April 30, 2011, the comedian Seth Meyers and President Barack Obama cracked jokes about a potential Trump election; they, in a sense, used playground rules to triple-dog-dare him to run by depicting the billionaire business man as a simpleton or a fool.

Seth Meyers joked, “Donald Trump has been saying that he will run for president as a Republican, which is surprising since I just assumed he’d be running as a joke.” The audience burst into roaring laughter. The billionaire Trump never cracked a smile. Meyers continued, “Donald Trump often appears on Fox, which is ironic because a fox often appears on Donald Trump’s Head” (Fusion07mp4, YouTube 2011). The blistering attacks continued for several minutes, personal and vitriolic. President Barack Obama declared on a number of occasions, almost in a panic of disbelief nearing the end of the 2016 elections that “Donald Trump will never be president.” Many on both the left (Democrat) and the right (Republican) of the political spectrum, despite their intense efforts, still do not understand why Trump is now president of the United States.

With so much energized effort to prevent the Trump presidency, why did it happen?

President Trump’s referent power comes from his natural ability to understand humor, and people are attracted to his personality because of his sense of humor. People should never crack jokes on people who are funnier than themselves. In a sense, the jokes against President Trump backfired because his ability to use humor strategically, his precise use of words, and his personality, combined with his business savvy, served as a cocktail of defeat for his much less able rhetorical rivals. Candidate Trump was able to infuse into his presidential campaign the fallacy of name calling, ad hominin insults on the person as campaign strategy, pilot tested in real time at his rallies. The ad hominin attacks did not consider the ideas of the opponents, but were purely mockery as a means to “misbrand” his political rivals, putting them off balance and on the defensive.

Candidate Trump’s rivals were now playing in an arena that was foreign to them; they had little chance of redirecting the public’s view back to their preferred brand (public image) once candidate Trump had tarnished their brand with one of his famous fallacies. For example, “Little Marco” for Marco Rubio, “Lying Ted” for Texas senator Ted Cruz, and “Low energy Jeb” for former Florida governor Jeb Bush. The blitzkrieg continued, with “Crooked Hilary.” Rarely were any of the political rivals, Republican or Democrat, able to repair their damaged brands. When Rubio tried and failed, by referring to candidate Trump’s hands as “small,” this hurt his image even further and compounded his branding problems, especially in his home state of Florida. Carly Fiorina, former HP CEO, emotionally responded to Trump’s barb directed at her when declaring that people should “look at her face, have you seen that face?” Her response of “every woman in America knows what Donald Trump meant,” was both too tame and possibly alienated her male voting base. Feeble attempts to redress candidate Trump’s rhetoric seemed to only worsen the branding issues for his political rivals. Their comebacks appeared boring and mundane.

Trump’s misbranding efforts simply were funnier than his opponents’ ineffective comebacks. Trump had the personality that attracted people to his message of nationalism, all while making the establishment politicians look more like what they had depicted him to be in 2011.

Source: www.youtube.com/watch?v=iWuv2txl_5M.

Expert Power

Expert power is based on competence. Expert power does not necessarily need to be explained; people just seem to know once a person with this type of power speaks. Many examples of this can be found in literature and in real life. The fictional character Sherlock Holmes had immense expert power. His reputation preceded him, because he had established a record of solving nearly impossible cases using inductive and deductive reasoning. In real life, few people would question the contributions to physics made by Albert Einstein (E = MC2); to literature made by Edgar Allen Poe (critical analysis of literature and the murder mystery); or to mathematics made by Rene Descartes (the father of analytic geometry and the Cartesian coordinate system). People with expert power are given respect through the deference of others. A person like Warren Buffet has both referent and expert power. Some leaders, however, acquire power by attaining position or status within an organization.

Legitimate Power

Legitimate power is based on the position or status earned or inherited. Some leaders have power because they earned it by climbing the corporate ladder, paying the price of hard work and sacrifice. Others might be born into a family that owns or has controlling shares of a business, and thus inherit a CEO position. In family owned businesses, succession planning typically names heirs to positions of power. In some cases, the person might not be the best suited for the position, yet could still be in control. Most organizations will have measures in place to ensure that only those who are competent are promoted within the structural hierarchy.

Reward Power

Reward power is based on the granting of positive stimuli to employees who work hard. A reward is a stimulus (positive reinforcement, tangible or intangible—verbal praise, a bonus, a certificate, flextime schedule, and more) used to reinforce a desired behavior exhibited by a subordinate. Rewards are used to keep behaviors consistent within the context of organized work routines. Leaders have power when they control things that others’ want and for which they are willing to behave in a desired way in order to receive the reward. Psychologists refer to this behavior as conditioning. The use of rewards to modify subordinates’ behaviors gives leaders extraordinary power of control.

Coercive Power

Coercive power is based on penalizing or punishing an employee. A punishment is a consequence imposed on an individual because he or she has engaged in an undesired behavior. Leaders sometimes supervise subordinates who will not respond to rewards. Personal and family problems, drug abuse, apathy, or feelings of inequity can result in nonresponse to a system of rewards. Some managers will use punishment to influence behaviors that they want subordinates to change. If a manager feels that a subordinate is unproductive or not supportive of the common goals, the manager may use coercive powers to get the person to either change or leave. “Two brains are better than one” is a cliché that is more often correct than incorrect, and this is why leaders often forge dyadic relationships with some employees. Leader–member exchange affords leaders power that can be very fruitful.

Climate

Organization communication climate is what you feel, hear, and sense when you watch employees interact. OCC includes degree of openness, trust, confidence, participation in decision making, and acceptance that exist in the work environment. Central to this humanistic approach to management is that subordinates participate in decision making. In an open and supportive climate, superiors and subordinates talk to each other, rather than superiors talking down to subordinates. Open OCC is marked by reciprocity—the openness and honesty within the relationship; feedback perceptiveness—sensitivity of supervisors to feedback; feedback responsiveness—the degree to which a supervisor gives feedback to subordinate requests or grievances; and feedback permissiveness—the degree to which supervisors permit and encourage feedback from subordinates (Gibb 1961).

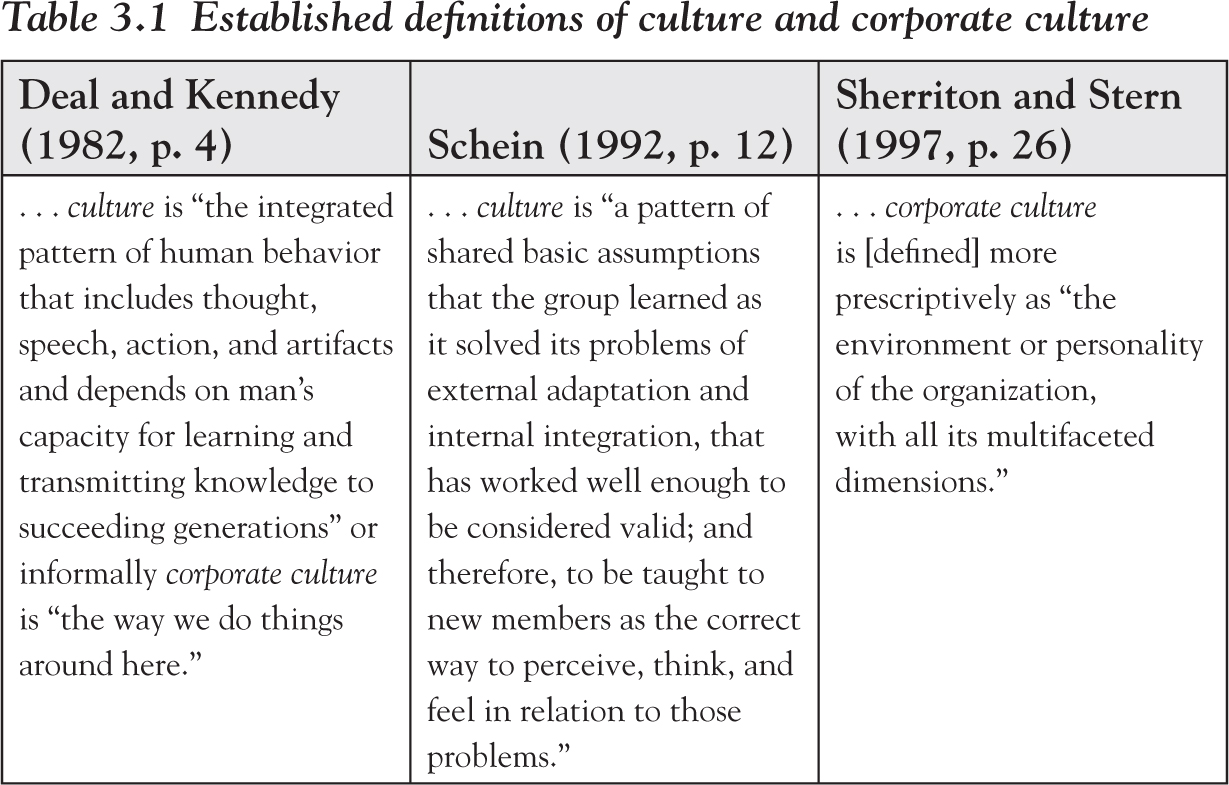

Essential to a positive OCC is communication openness, information adequacy, and communication supportiveness. When information is open, employees have a grasp of what is happening in the organization. If an organization is open, adequate information is available for all employees. When leaders keep employees in the loop, they are being supportive. When leaders leave employees out of the loop because of lack of trust or power hoarding, they are being defensive. Defensive behaviors are not conducive to building a positive OCC. Managers have the critical role in the communication process of keeping everyone informed. Executive management must empower, engage, and enable their subordinates to communicate and direct the flow of information in the organization. The open and supportive OCC model presented in Figure 3.1 shows that information must flow smoothly between all levels of the organization and across functional areas (Robertson 2003).

Potential traps exist for leaders in interpersonal communications between the manager and the employees, especially when the relationship is new. The best way for the executive to avoid the traps that result from failed leadership is to establish positive impressions with employees from the very beginning. Research has indicated that trust and commitment do not just happen automatically, but rather that they are forged and maintained by managers communicating effectively (Appelbaum et al. 2013).

At times, it may be necessary to reshape some of the networks that have developed in a firm in order to have a better OCC. Changing the OCC within a firm is not easy, and the ease of changing it depends on the number of subgroups or silos within the organization. You may also find that the structure of these silos differs because of the various types of work that occur within them. While workers communicate one way within their group, they may need to learn how to communicate effectively with other groups.

It is vital that managers know how information flows in the organization. An organization chart by design unintentionally promotes the formation of silos within the organization and impedes the flow of communication between functional areas. The need to facilitate communication increases with more involved organizational structures. Some organizations do not have an organization chart in an effort to enable employees to communicate with whomever they need. The Japanese developed what is known as the quality circle, where everyone is equal and can talk to other individuals no matter what their level is within the organization. Examining the organization chart and considering the limitations it may inadvertently put on the employees is important to communication strategy. If the chart is making managing too bureaucratic, then a change may be necessary. You can use the model in Figure 3.1 as a self-help tool to become a more effective manager. Frequently, employees speak past one another cross-functionally because their working vocabularies are different. Learning the language of other functional areas takes time because departmental employees often have limited knowledge of what happens in the rest of the company. However, this lack of understanding decreases when employees listen, ask questions, and learn to rephrase technical information so that others can understand it. Working in cross-functional teams helps to open lines of communication across the organization.

In an organization with a supportive communication climate, its members write and speak descriptive messages that are clear and specific without judgmental statements or words. In a supportive communication climate, problems will be posed as mutual problems to be worked on, communication will be open and honest in spontaneous messages, employees at all levels will be empathetic to the feelings and thoughts of others, messages will indicate an equality of worth between all levels of employees, and point-of-view messages will be posited as provisional and open to investigation. If an organization is not supportive, the climate will be defensive and not conducive to effective communication.

Supportive communication requires the ability to communicate and manage attitudes as well as information. Organizations can benefit from an examination of managers at all levels concerning their experience, judgment, intelligence, relationships, and insights, and then design training programs that help managers become better communicators. This may mean looking at “who does what,” “where is it done,” and “how is it done.”

OCC starts with the CEO and board of directors and extends throughout the levels of management. Many managers are not only dealing with people in their home country but also with employees, customers, or suppliers in other countries. They may be virtually supervising employees from other nations and cultures. Employees with different cultural backgrounds can also find it difficult to assimilate into the existing organization. It is necessary that their managers spend time learning about their cultural differences and helping the person feel like a part of the overall organization. The Window into Practical Reality 3.2 exemplifies how poor OCC can be detrimental to business success.

Window into Practical Reality 3.2

The Rise and Fall of a Titan

CBS News reported on February 9, 2005, that Hewlett-Packard’s (HP’s) board of directors had fired Carly Fiorina after a 6-year reign as CEO. Fiorina’s power-driven move to acquire Compaq was seen as too risky by many, and some charged her with inability to hear her constituents. This cited communication failure led to covert rebellion among the ranks and resulted in a very poor OCC during much of Fiorina’s reign. The board accused Fiorina of failing to execute the planned strategy. She also had a strained relationship with the son of one of HP’s late cofounders, HP director Walter Hewlett who openly opposed the Compaq acquisition because he felt it was overpriced.

The problem was probably not so much that Fiorina did not perform as the board of directors expected, but that she would not or could not hear her dissenters’ concerns. Media reported that Fiorina’s drive to acquire Compaq interfered with her managerial interaction skills (Vries 2005).

Using the complete OCC model shown in Figure 3.1, can you identify some of the skills that Fiorina obviously used to climb to the top of HP’s hierarchy to become its CEO? Conversely, can you use the model to describe how her violating of these fundamentals led to her inevitable ouster?

As an organization grows, it generally will add departments and divisions, making communication connections grow exponentially. As a firm grows, the individuals joining the organization are likely to be more diverse, which leads to managers having to learn about their employees’ differences and how they communicate. These differences could be due to their ethnic background, native language, gender, or anything else that differentiates people. As a firm grows, the management must also consider new ways to organize processes.

External stakeholders gauge the organization’s communication climate by media messages and the way that customers and employees talk about the firm. A firm’s external prestige is a direct result of employees’ buy-in to the goals, values, and achievements of the organization. The communication climate affects how employees identify with the firm and project their impressions externally.

Culture

Subordinates can undermine managerial authority. Failing to understand the cultural forces at play can jeopardize managerial authority and ultimately impact the bottom line (Manzoni and Barsoux 2009). When managers do not have knowledge of organizational culture, it is impossible for them to change a traditional, rigid organization of yesterday into one that is flexible and evolving for tomorrow (Flannery, Hofrichter, and Platten 1996).

Very little was written on corporate culture prior to 1979 (Kotter and Heskett 1992). More recently, there has been a great deal of research on corporate culture. Studies have addressed how leaders should examine the artifacts, espoused values, and basic underlying assumptions as layers of organizational culture. What is clear is the strong influence managerial communication (MC) has on shaping corporate culture by steering the entire direction of the organization toward prosperity or ruin.

The common managerial practice of attempting to decentralize decision making prior to assessing meaning in culture is not recommended. Attempts to change organizational culture cannot resolve business problems when there is incomplete knowledge of the current organizational culture. Changes in culture must accompany changes in values, beliefs, and core assumptions.

Even though an adaptive culture cannot account for 100 percent of corporate performance, developing successful strategies to deliver value to major constituencies is very important. Culture can be either the brakes or the fuel for the engine of success of an organization and is just as important as the primary functions of finance and information technology (Rigsby and Greco 2003). Organizational culture influences employees’ perspectives, just as societal cultural shapes citizens. Individuals learn their societal culture and share their culture first with their family and then with the broader community in which they live. To disseminate the culture, the existing members must share their beliefs and values with the next generation or newcomers, so that the new members understand what is required to be a member of the culture. Business culture is learned in much the same way as is societal culture.

Established Layers of Culture

Weick (2001) argues that meaning is distinct from decision making by asserting that meaning precedes decision making. He argues that managers must understand the nature of what is happening before they can decide on what to do about it. His assessment is that even though centralized and decentralized authority are both valuable in certain situations, understanding culture can make decentralized decision making more desirable. Being in the loop as culture is forming, reforming, and affecting outcomes is a way for top management to effectively gauge, anticipate, and dislodge the potential hazards of unhealthy communications (both symbolic and explicit), resulting in organizational cultures that go awry. Corporate culture can drive performance and the core values that comprise corporate culture. The meaning and interpretation of organization and corporate culture content can be broad, spanning all tiers and functions of management.

Other theorists have offered additional definitions essential to the consideration of organizational culture. Schein (1992) stated that (1) artifacts are all the phenomena that are visible, (2) espoused values are confirmed by shared social experiences of group members and this layer of conscious culture can be used to predict much of the behavior that can be observed at the artifactual level, and (3) basic underlying assumptions become embedded in culture when solutions to group problems work repeatedly.

Similarly, Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner (1998) stated that the (1) outer layer is explicit products that are the observable reality of the culture such as food, language, or shrines; (2) the middle layers are norms and a mutual sense of a group’s right and wrong, and values are those beliefs that determine or define what the group might think is good and bad; and (3) the core is made of assumptions about existence, which are implicit to the members of the culture to increase people’s effectiveness at solving problems.

Shared meanings are man-made and transcend the people in the culture. The more visible the culture, the easier it is to change; the less visible the culture, the more resistant it is to change. A good example of the reason artifacts, the observable most visible reality of the culture, matter in shared meanings is shown in the Window into Practical Reality 3.3.

Window into Practical Reality 3.3

Books on Shelves, Diplomas, and Awards Displayed on Walls Matter!

Every year the college professors are assembled together to receive annual teaching awards based on student surveys and student nominations. Input from department heads are also considered in which faculty members would receive the three awards, one for each department in the college. There is often a $2,000 cash prize associated with the award.

In addition to teaching and research, faculty in the particular college are required to advise students on their course selections, career interests, and any other subjects relating to the students’ success. One assistant professor is respected in the college, and has had some significant articles published in her field of finance, which has garnered her some respect in the field. Nonetheless, she has not received a teaching award. Moreover, the college of business has very few female faculty, and this assistant professor is the only one teaching finance at both the graduate and undergraduate levels.

The finance professor is always available in her office during office hours and is willing to meet any of her students by appointment too. She has had no complaints from any students on any serious matter. The assistant professor conveys her concerns with a colleague in the college who is a full professor in the management area about her desire to receive the award, especially since she is up for tenure in just 1 year. The full professor of management asked the assistant professor of finance a very interesting question.

He asked, “What does your office look like?”

She answers, “About the same as it did when I moved in.”

He replied, “That was about five years ago, correct?”

She replied, “Yes, just about.”

The full professor tells the assistant professor, “Do you think it is about time that you dust off some of your books, diplomas, and awards and move them into your office space? Students care about these things.” He continues, “apparently your office does not reflect to your students who you are really.” The assistant professor spent some money on having her three college diplomas, including her PhD degree, framed and hung them on her office walls. She relocated about 200 of her books, many of which she had been collecting since high school from her home office. She also posted in plain sight three framed awards that she had received from finance conferences she attended over the years.

When students visited her office, a frequent question to her was, “Wow! Did you read all these books?!” The assistant professor of finance proudly declared, “Yes, I did,” to any student who asked. The very next semester, many students nominated the assistant professor for the teaching award, and she received the teaching award right in time for her tenure application.

- Do you suspect that when the assistant professor of finance changed the artifacts in her office space that she changed the shared meaning in the culture among students in the college of business?

- Was it merely a coincidence that she received the award for the first time after she hung the diplomas and awards and moved a lot of books into her office space?

Formal and Informal Networks

Studies have shown that performance increases when the CEO and marketing vice president share the same vision and communicate that vision vertically to the rest of the firm. How to share that vision vertically; however, is not always clear. Top management must obviously communicate adequately with the functional managers, and the functional managers must communicate with their subordinates. Maintaining an organizational structure which promotes effective vertical communication of a company’s vision requires formal processes.

Formal Networks

The communication structure of an organization is both formal and informal. The more formal the structure, the more messages have to follow channels depicted in the formal organization chart of the company; the more informal the structure, the easier it is to go directly to the person with whom you wish to communicate.

In very formal networks, information moves down the depicted lines of authority, and employees do not bypass their bosses when communicating with others in the organization. The employee communicates upward through the direct supervisor, who then will send the message up the chain of command. Certain information is typically communicated more formally, such as common rules, regulations, standard operating procedures, plans, schedules, and forecasts. A formal organizational structure will often require that written channels of communication be used for formalized decision making. Coordination must exist between the different groups within the organization in order to accomplish the overall goals of the organization.

Katz and Kahn (1966) are credited with identifying the three directions of communication flow: communications down the line—down to the workers; horizontal communications—between departments; and communication upward—up toward top management.

Upward communication is used to keep management informed. Upward communication may happen through reports, meetings, or informal communications. If top management encourages upward communication, a company’s leadership is more likely to learn about the concerns and suggestions that employees have.

Downward communication is generally used to instruct workers, build and maintain the morale and goodwill of the workers, keep routine and special activities moving smoothly and efficiently, and to encourage upward communication. Employees want guidelines and information from management, and management wants input and feedback from employees.

Horizontal (lateral) communication strengthens interpersonal relationships across departments and units within the company. Such an exchange helps to minimize conflict, promote understanding, and increase coordination between departments or units. Getting others to communicate their needs is a two-way process and generally starts with how managers encourage and motivate their employees. It is helpful for managers to start conversations by sharing their skills and knowledge and empowering the employees to do the same.

Some organizations have a culture of everyone being allowed to communicate with anyone in the firm, at any level. Other organizations want communication to travel along established routes—subordinate to supervisor to superior. Of course, in the first type of culture, it is very easy to quickly let people at the top know what is happening and vice versa; however, people in the middle may be left out. The use of e-mail has increased broad awareness in many organizations, as messages can be copied to multiple recipients simultaneously.

Given that organizations often make strategic changes due to internal or external pressures, top managers must skillfully use ways to quickly communicate vertically to multiple recipients throughout the firm. Managers at all levels must help to build everyone’s understanding, an identity with the company, and commitment to the strategy’s formulation, dissemination, and implementation. It is also necessary that top management encourage and actually listen to responses from those at varying levels in the organization.

Informal Networks

In more informal networks, everyone can communicate directly with everyone else. You would still need to keep your boss informed of what you are doing, but there is no pressure on you to only tell your boss. The formality or informality of an organization generally starts at the top and depends upon the technical, political, and economic environment of the organization. You will find organizations such as Microsoft that are very informal and organizations such as General Motors that are more formalized.

Much of an organization’s communication takes place through informal processes. Therefore, key linkages are essential. These linkages between the areas of the firm determine the frequency of communication: Who receives the communication, and whether the meaning of the communication is shared. Informal communication networks are like spiderwebs because various areas are interconnected no matter how far they are from the top. Frequent communication between the functional areas and top management will impact both functional and organizational performance. If a firm does not have shared understanding, there will be barriers to successful strategic plan implementation (Rapert, Velliquette, and Garretson 2002).

The grapevine is a form of informal communication. With Twitter and other social media, jamming, texting, e-mail, and other technology, it is easy for information to be passed around a company very quickly. Gossip being transferred only at the water fountain is a thing of the past. What makes grapevines important to managers is that they typically carry more information than formal networks. While the grapevine may distribute gossip, rumors, and half-truths, it also frequently provides accurate information. This information can be useful to managers, who should know how and when to use the grapevine.

What makes individuals pass on certain information, yet desire other information? Typically, this decision is based on the salience or importance of the information to the individual, the effect of the channel chosen, and the cultural norms of the organization. Johnson and others (1994) found that employees use informal channels more than formal channels in business. Roles tend to dictate the number of formal and informal communication channels that are used. Also, employees scrutinize formal communication for characteristics such as editorial tone more than they do with information from informal channels.

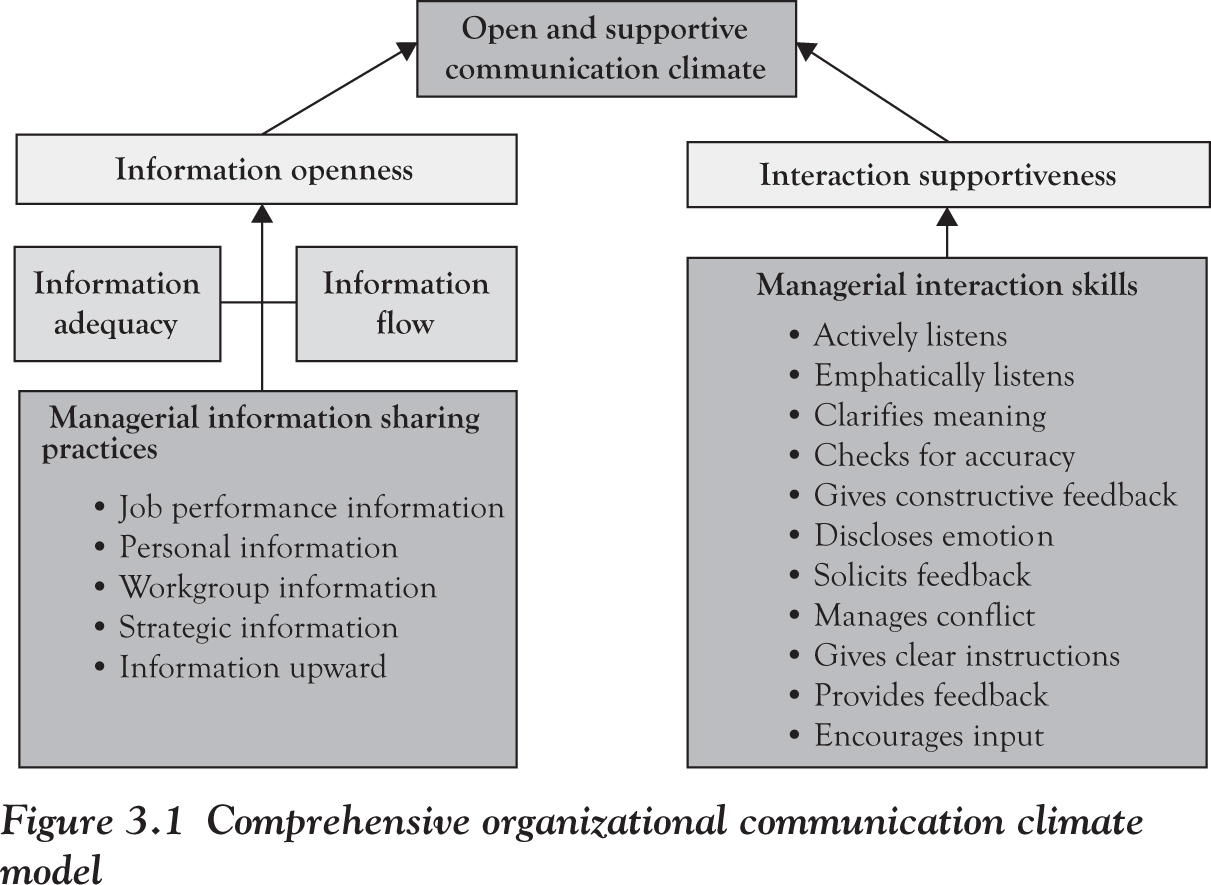

Figure 3.2 shows how important it is for managers to dial into the other jobs employees do, in addition to their formal assignments (Bell 2009). It is essential that you as a manager know the quality of the communications radiating from the hidden hierarchy. The phone connected directly to the hidden hierarchy in Figure 3.2 is a visual reminder to managers of the importance of being in the loop of informal corporate cultural communications.

Deal and Kennedy (1982) created the metaphors of spies, storytellers, priests, whisperers, cabals, and gossips to describe the various types of communication activities occurring in the cultural network of the hidden hierarchy. These metaphors describe each of the other jobs people do at work within a MC context. Spies are people who are loyal in the network and those who keep others informed of what is going on. A storyteller is a person who can change reality by interpreting what goes on in a company to suit their own perception. Priests tend to be worriers, responsible for guarding the company’s values and keeping the flock together. Whisperers work like Machiavelli from behind the throne, but without a formal portfolio—the source of their power is the boss’s ear. Cabals plot a common purpose by joining together in unions that provide personal gain and advancement. Gossips will name names, know dates, salaries, and events that take place, and they carry the day-to-day trivial information cautiously appreciated by most.

Values and styles affect the identification and management of ethical problems, causing unintentional ethical dilemmas. Unfortunately, leaders are sometimes the architects of negative cultures. Dent and Krefft (2004) assert that two cultures exist in any organization, the one that results from fear, dishonesty, and denial and the one that invigorates creativity and integrity. Management determines which culture dominates. Organizational cultures are paradoxical because they contain both productive and counterproductive elements of culture. This factor helps explain why the bankers played hot potato with subprime mortgages, even though nearly every executive knew the risks. Questions emerge as to why some bankers behaved ethically while others did not: What elements in some financial institutions’ cultures steered them toward fortitude amid the subprime lending free-for-all, and what elements in other financial institutions’ cultures steered them toward depravity (falsifying documents, hiding audit documents from the Securities and Exchange Commission [SEC], repackaging bad debt, ostracizing whistle-blowers and those refusing to violate the law, policy, and procedure, and so on)?

Summary

Leadership is the process of providing forward movement for the organization and vision for the future. Leaders strive to achieve common goals for the common good. Power can be used for the common good or for selfish purposes. Six bases of power are referent power, expert power, legitimate power, reward power, coercive power, and the leader—member exchange. The OCC is determined by the degree of openness, trust, confidence, participation in decision making, and acceptance. OCC comprises both actions and attitudes and is highly influenced by how supervisors define their roles and the roles of subordinates within the firm.

The layers of culture include (1) artifacts, the most visible layer that contains all the phenomena that can be seen, heard, or felt when a person first encounters a new group with an unfamiliar culture; (2) espoused values, which are confirmed by shared social experiences of group members that can be used to predict much of the behavior observable at the artifactual level; and (3) basic underlying assumptions, which become embedded in a culture when solutions to group problems work repeatedly.

The three directions of communication flow are down the line communication that originates with managers and is directed down to the workers; horizontal communication that occurs between members of different lateral departments; and upward communication that begins with employees and moves up toward top management.

In a company with a formal communication structure, employees avoid bypassing their bosses when communicating with others in the organization. In formal communication, an employee always tells the direct supervisor, who then will send the message up the chain of command. In informal organizations, everyone can communicate directly with everyone else. The grapevine is a form of informal communication that managers can use to their advantage. Technology facilitates the easy and fast movement of information around a company.