Chapter 6

Differentiating Customers by Their Needs

Strive not to be a success, but rather to be of value.

—Albert Einstein

Having a good knowledge of customers’ value is certainly important, but to use customer-centric tools and customer strategies to increase a customer’s value, the business must be able to see things from the customer’s perspective, with the realization that there are many different types of customers whose perspective must be individually understood. Value differentiation by itself will not give a company this perspective. Think about it: Except for very frequent flyers, customers don’t usually know or care what their value is to a business. Customers simply want to have their problem solved, and every customer has his own slightly different twist on how the process should be handled, even if more than one customer wants a problem solved a particular way. The key to building a customer’s value is understanding how this customer wants it solved. So one key to building profitable relationships is developing an understanding of how customers are different in terms of their needs and how such needs-based differences relate to different customer values, both actual and potential. What behavior changes on the customer’s part can be accomplished by meeting those needs? What are the triggers that will allow the firm to actualize some of that unrealized potential value?

In this chapter, we consider the different needs of different customers and the role that customer needs to play in an enterprise’s relationship-building effort. In most situations, it makes sense to differentiate customers first by their value and then by their needs.1 In this way, the relationship-building process, which can be expensive, will begin with the company’s higher-value customers, for whom the investment is more likely to be worthwhile. (An important exception to this general rule, however, applies to treating different customers differently on the Internet through mobile and other devices. On the Web, the incremental costs of automated interaction are near zero, so it makes little difference whether an enterprise differentiates just its top customers by their needs or all its customers.)

Definitions

Before going too much further, let’s pause to define the important terms relevant to this discussion.

Needs

When we refer to customer needs, we are using the term in its most generic sense. That is, what a customer needs from an enterprise is, by our definition, what she wants, what she prefers, or what she would like. In this sense, we do not distinguish a customer’s needs from her wants. For that matter, we do not distinguish needs from preferences, wishes, desires, or whims. Each of these terms might imply some nuance of need—perhaps the intensity of the need or the permanence of it—but to simplify our discussion, we will refer to them all as “needs.”

It is what a customer needs from an enterprise that is the driving force behind the customer’s behavior. Needs represent the “why” (and often, the “how”) behind a customer’s actions. How customers want to buy may be as important as why they want to buy. The presumption has been that frequent purchasers use the product differently from irregular purchasers, but it may be that they alternatively or additionally like the available channel better. For that matter, it may be that they like the communications channel better. The point is that needs are not just about product usage but about an expanded need set (which we discuss fully in Chapter 10) or the combination of product, cross-buy product and services opportunities, delivery channels, communication style and channels, invoicing methods, and so on.

In a relationship, what the enterprise most wants is to influence customer behavior in a way that is financially beneficial to the enterprise; therefore, understanding the customer’s basic need is critical. It could be said that while the amount the customer pays the enterprise is a component of the customer’s value to the enterprise, the need that the enterprise satisfies represents the enterprise’s value to the customer. Needs and value are, essentially, both sides of the value proposition between enterprise and customer—what the customer can do for the enterprise and what the enterprise can do for the customer.

Customers

Now that we have defined both customer value and customer needs, we should pause for a reminder of the definition of customer before continuing with our discussion. In Chapter 1, we defined what we mean by customer. On the surface, the definition should be obvious. A customer is one who “gives his custom” to a store or business; someone who patronizes a business is the business’s customer. However, the overwhelming majority of enterprises serve multiple types of customers, and these different types of customers have different characteristics in terms of their value and their individual needs.

A brand-name clothing manufacturer, for instance, has two sets of customers: the end-user consumers who wear the clothes and the retailers that buy the clothes from the manufacturer and sell them to consumers. As a customer base, clothing consumers do not have as steep a value skew as, say, a hotel’s customer base, even though some consumers might buy new clothes every week. (In other words, the discrepancy in value between the most valuable consumers and the average will generally be smaller for a particular clothing merchant.) But all consumers of the clothing manufacturer do want different combinations of sizes, colors, and styles. So even though clothing consumers may not be highly differentiated in terms of their value, they are highly differentiated in terms of their needs. Retailer customers also have very different needs: Some need more help with marketing, or with advertising co-op dollars, or with displays. Different retailers will have very different requirements for invoice format and timing or for shipping and delivery. They may need different palletization or precoded price tags. Interestingly, retailers will also vary widely in their values to the clothing manufacturer—with much more value skew than consumers will show. Some large department store chains will sell far more stock than can a local mom-and-pop clothing shop. And some growing online retailers have stocking and timing issues that are quite different from retailers who sell mostly through in-store displays. Thus, retailer customers display high levels of differentiation in terms of both their needs and their value.

For the clothing manufacturer, if the enterprise expresses an interest in improving its relationships with its customers, the question to answer is: which customers? And this is, in fact, the type of structure in which most enterprises operate. They won’t all sell products to retailers, but the vast majority of businesses do have distribution partners of some kind—online and bricks-and-mortar retailers, dealers, brokers, representatives, value-added resellers, and so forth. Moreover, a business that sells to other businesses, whether these business customers are a part of a distribution chain or not, really is selling to the people within those businesses, people of varying levels of influence and authority. Putting in place a relationship program involving business customers will necessarily entail dealing with purchasing agents, approvers, influencers, decision makers, and possibly end users within the business customer’s organization, and each of these people will have quite different motivations in choosing to buy.

The logical first step for any enterprise embarking on a relationship-building program, therefore, is to decide which sets of customers to focus on. A relationship-building strategy aimed at end-user consumers can (and, in most cases, should) involve some or all of the intermediaries in the value chain in some way. However, it is a perfectly legitimate goal to seek stronger and deeper relationships with a particular set of intermediaries. The basic objective of relationship building with any set of customers is to increase the value of the customer base; thus, it’s important to understand from the beginning exactly which customer base is going to be measured and evaluated. Then, when focusing on that customer base, the enterprise must be able to map out its customers in terms of their different values and needs.

It is easy to confuse a customer’s needs with a product’s benefits. Companies create products and services with benefits that are specifically designed to satisfy customer needs, but the benefits themselves are not equivalent to needs. In traditional marketing discipline, a product’s benefits are the advantages that customers get from using the product, based on its features and attributes. But features, attributes, and benefits are all based on the product rather than on the customer. Needs, in contrast, are based on the customer, not the product. Two different customers might use the same product, based on the same features and attributes, to satisfy very different needs.

When it focuses on the customer’s need, the enterprise will find it easier to increase its share of customer, because ultimately it will seek to solve a greater and greater portion of the customer’s problem—that is, to meet a larger and larger share of the customer’s need. And because the customer’s need is not directly related to the product, meeting the need might, in fact, lead an enterprise to develop or procure other products and services for the customer that are totally unrelated to the original product but closely related to the customer’s need. That’s why focusing on customer needs rather than on product features often will reveal that different customers purchase the same product in order to satisfy very different individual needs.2

Differentiating Customers by Need: An Illustration

Consider a company that manufactures interlocking toy blocks for children, such as Lego® or Mega Bloks, and suppose this firm goes to market with a set of blocks suitable for constructing a spaceship. Three 7-year-old children playing with this set of blocks might all have different needs for it. One child might use the blocks to play a make-believe role, perhaps assembling a spaceship and then pretending to be an astronaut on a mission to Mars. Another child might enjoy simply following the directions, meticulously assembling the same spaceship in exact detail, according to the instructions. Once the ship is built, however, the child would be less interested in it. A third child might use the block set meant to construct a spaceship to build something entirely different, drawn from his own vivid imagination. This child simply wouldn’t enjoy putting together a toy according to someone else’s diagram.

Each of these three children may enjoy playing with the same set of blocks, but each is doing so to satisfy a different set of needs. Moreover, it is the child’s need that, if known to the marketer, provides the key to increasing the child’s value as a customer. If the toy manufacturer actually knew each child’s individual needs, and if it had the capability to deal with each child individually, by treating each one differently, it could easily increase its share of each child’s toy-and-entertainment consumption. For example, for the “actors,” it might offer costumes and other props, along with storybooks and videos or DVDs, to assist the children in their imaginative role-playing activities. For the “engineers,” it might offer blueprints for additional toys to be assembled using the spaceship set; or it might offer more complex diagrams for multiset connections if the company knew all the sets owned by this child. And for the more creative types, the “artists,” the company might provide pieces in unusual colors or shapes, or perhaps supplemental sets of parts that have not been planned into any diagrams at all.

We can use this example to compare and contrast the different roles of product attributes and benefits versus customer needs. Exhibit 6.1 shows that each product attribute yields a particular benefit that consumers of the product can enjoy.

Exhibit 6.1 Product Attributes versus Benefits

| Product Attribute | Product Benefit |

| Toys in fantasy configurations | Recognizable make-believe situations |

| Colorful, unusual shapes that easily interlock | Large variety of interesting combinations |

| Meticulously preplanned, logically detailed instructions | Complex directions that are nevertheless easy to follow |

It should be easy to see that each product attribute can be easily linked to a particular type of benefit. And the benefits will appeal differently to different customers, but each benefit springs directly from each attribute. If, instead, we were to map out the types of customers who buy this product, based on the needs of these end users as just outlined, we could then list the additional products and services that each type of customer might want, based on what that customer needs from this and other products. If we just looked at our actor, artist, or engineer end-user customers to see which needs they wanted to address, then our table would look like Exhibit 6.2.

Exhibit 6.2 Beyond Benefits: Customer Needs

| Customer Need | Additional Products and Services |

| Actor: Role-playing, pretending, fantasizing | Costumes, videos, storybook, toys |

| Artist: Creating, making stuff up, doing things differently | Colors and paints, unique add-ons, nonsequitur parts |

| Engineer: Solving problems, completing puzzles | More diagrams, problems, logical extensions |

This is only a hypothetical example, of course, and we could easily come up with several additional types of customers, based on the needs they are satisfying with these construction blocks. For instance, there might be some girls who want the spaceship set of blocks because they are really interested in rockets, outer space, and other things astronautical. Or there might be some boys who want the set because they are collectors of these kinds of building-block toys, and they want to add this to a large set of other, similar toys. Or there might be others who like to use this kind of toy to invite friends over to work together on the assembly. Any single child might, in fact, have any combination of these needs that she wishes to satisfy, either at different times or in combination.

The point is, by taking the customer’s own perspective, the customer’s point of view—by concentrating on understanding each different customer’s needs—the enterprise will more easily be able to influence customer behavior by meeting his needs better, and changing the future behavior of a customer by becoming more valuable to him is the key to realizing additional value from that customer.

Understanding Customer Behaviors and Needs

Understanding the differences in customer behaviors, and the needs underlying these behaviors, is critical for all stages in a company: from product development to financial consolidation, from production planning to strategic planning or marketing budgeting. All decisions and activities made by customers in order to evaluate, purchase, use, and dispose of any goods or services offered by a company are subject to being captured in the transactional record and are subject to behavioral analysis.

A customer’s need is what she wants, prefers, or wishes while her behavior is what she does or how she acts in order to satisfy this need. In other words, “needs” are the “why” of a customer’s actions, and “behaviors” are the “what.” Behaviors can be observed directly, and from behaviors an enterprise can often infer things about a customer’s needs. This hierarchy or logical ordering in these two notions, that customer needs drive customer behaviors, is a critical pillar for the relationship-marketing practitioner.

All companies want to understand why and how customers make their buying decisions. Factors that affect this process are analytically assessed and examined, then reexamined. Clearly segmenting customers by their needs and behaviors will allow an enterprise to identify and describe different categories of customers and ensure that its marketing efforts are effective for each of these groups.

Characterizing Customers by Their Needs and Behaviors

Companies now have comprehensive systems and processes to capture and store customer data covering almost every aspect of a customer’s relationship with a firm. Descriptive characteristics like gender, age, and income, along with transactional data such as interactions, purchases, and payments, and usage-related measures such as service requests—all this information can be captured and stored by the enterprise. The information companies store on individual customers is usually referred to as customer profiles.

Let’s consider a customer database in a bank environment where there has been a significant information technology (IT) investment. The department in charge of business intelligence can describe the same customer in two different ways, providing two different profiles:

- Customer is married, is European, has two children, lives in an upscale neighborhood, and is a member of a frequent-flyer program.

-

Customer visited the online banking site once a week over the past six months, always visiting the site at least once in the first three days of each month; has a tenure of more than two years; uses investment tools; checks her statement and balance regularly; pays her credit debts promptly and has a clear credit history; and has increased her assets under management by 5 percent in the past three months.

The first profile is demographic. It is a set of characteristics that are less dynamic compared to the second profile. These data probably are stored by other companies doing business with this customer as well, and perhaps even by the bank’s own competitors. The second profile is behavior-based, and involves a record derived from what the customer is actually doing or has done in the past with this bank. Details of her behavior are dynamic and only available inside the bank’s database, thus providing the bank with an opportunity for competitive advantage—if the bank uses the information to serve this customer better than other firms that do not have the specific customer information.

Both profiles are important in their own ways. For someone preparing an advertising campaign, creating a marketing strategy, or deciding on content for a piece of marketing communication, the first profile is very useful, because it defines the customer (or the market) at a macro level and provides clues to editorial direction. If someone in the bank’s marketing department just wanted to describe this customer to someone else, this is the profile they would probably use. The second type of profile, however, is about needs, action, and behavior and is certainly more relevant than the demographic profile for any executive at the bank who really wants to know what customers are doing. Will this customer visit again? Will she buy again? What is the risk she will default on her credit or cost the bank money? These are the questions an executive tries to answer by looking at behavioral records.

But let’s now assume that the business intelligence department can produce a third profile on this customer as well:

- The customer manages the future of her family and her children very carefully, and this is her primary motivation while using the bank’s products and services. She is comfortable with technology and enjoys engaging with the bank online rather than having to visit branches, because she is always pressed for time.

This new profile actually defines why this particular customer uses the banking services she uses. It shows why she prefers online services and why she has accumulated an investment account. Moreover, while different customers will have different needs, many of these needs will be shared by others. Needs describe the root causes behind a customer’s actions, whether those actions include choosing to work with another bank or staying loyal to this bank and subscribing to a new service.

It’s important to get the sequence right. Needs are not based on a customer’s value or behavior. Rather, a customer’s needs drive her behavior, and her behavior is what generates her value to the business. The needs just described are not generic, true- for-everybody statements, such as “I want to have cheaper products with higher quality.” They are very specific needs, valid only for some portion of the bank’s customers.

Behaviors are the customers’ footprints on a company. They represent the evidence of customers trying to meet their needs, and this evidence is likely to be accumulated in different company systems over different periods of time.3

Why Doesn’t Every Company Already Differentiate Its Customers by Needs?

It is reasonable to ask, if the logic outlined is so compelling, why toy manufacturers and other firms aren’t already attempting to differentiate customers by needs. Many firms that have traditionally sold through retailers still believe that the hurdles to doing so are sizable. For example, most toy manufacturers sell their products through retailers and have little or no direct contact with the end users of their products. In order to make contact with consumers, a manufacturer would have to either launch a program in cooperation with its retailing partners or figure out how to go around those retailers altogether—a course of action likely to arouse considerable resentment among the retailers themselves. So the majority of a manufacturer’s end-user consumers are destined to remain unknown to the enterprise. Moreover, even if it had its customers’ identities, the manufacturer still would have to find some means of interacting with the customers individually and of processing their feedback, in order to learn their genuine needs. Then it would have to be able to translate those needs into different actions, requiring a mechanism for actually offering and delivering different products and services to different consumers. Nevertheless, some companies, such as Lego, still sell through storefront and online retailers, but also sell directly to consumers through a Web site. Lego, for instance, offers free shipping every day at http://shop.lego.com/en-US/. Its Web site is highly interactive, keeping track of what a particular kid likes to do there by use of login and password, and a (free) subscription magazine, thereby logging an address, all in addition to their store site, which offers some exclusive parts and sets you can’t get elsewhere.

Doing all this sets up a direct competitive relationship with the very retailers that the manufacturers still depend on for a large percentage of sales. And real resources are required to take these steps to build direct relationships. These obstacles make it very difficult for toy manufacturers simply to leap into a relationship- building program with toy consumers at the very end of the value chain. That said, the manufacturer does not have to launch such a program for all consumers at once. Rather, it could start by identifying its most avid fans, its highest-volume, most valuable consumer customers. Perhaps it could devise a strategy for treating each of those highly valuable customers to individually different products and services, in a way that wouldn’t undermine retailer relationships. A Web site designed to attract and entertain such consumers could play this kind of role, and the toymaker could take advantage of social networking connectivity as well. Although the toy manufacturer still would encourage other shoppers to buy its products in stores, perhaps it could begin to offer more specialized sets and pieces directly to catalog and Web purchasers. If it had a system for doing this, launching a program designed to make different types of offers to different types of end-user consumers—based on their individual needs—would be much simpler and would, for practical reasons, start that process with customers of high value.

Indeed, the primary reason so many firms are now attempting to engage their customers in relationships is that the new tools of information technology—not just the Internet in general and social networking sites in particular, through an increasing number of devices, but customer databases, sales force automation, marketing and customer analytics applications, and the like—are making this type of activity ever more cost efficient and practical.4 But for an enterprise engaged in relationship building, the “hot button,” in terms of generating increased patronage from the customer, is the customer’s need.

Categorizing Customers by Their Needs

In the end, behavior change on the part of the customer is what customer-based strategies are all about. To capture any part of a customer’s unrealized potential value requires us to induce a change in the customer’s behavior; we want the customer to buy from an additional product line, or take the financing package as well as the product, or interact on the less expensive Web site rather than through the call center, and so forth. This is why understanding customer needs is so critical to success. The customer is master of his own behavior, and that behavior will change only if our strategy and offer can appeal persuasively to his very own needs—not what we want his needs to be or some average of needs for a bunch of different customers. Being able to see the situation from the customer’s point of view is key to any successful customer-based strategy.

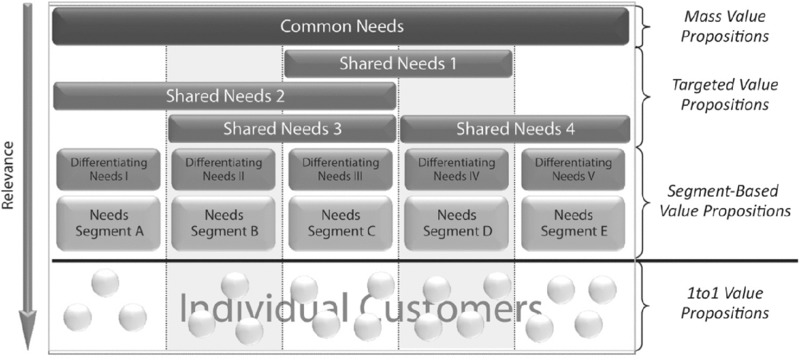

But in order to take action, at some point, different customers must be categorized into different groups, based on their needs. Clearly, it would be too costly for most firms to treat every single customer with a custom-designed set of product features or services. Instead, using information technology, the customer-focused enterprise categorizes customers into finer and finer groups, based on what is known about each customer, and then matches each group with an appropriately mass-customized product-and-service offering. (More about mass customization and the actual mechanics of the process in Chapter 10.)

One big problem is the complexity of describing and categorizing customers by their needs. There are as many dimensions and nuances to customer needs as there are analysts to imagine them. For consumers, there are deeply held beliefs, psychological predispositions, life stages, moods, ambitions, and the like. For business customers, there are business strategy differences, financial reporting horizons, collegial or hierarchical decision-making styles, and other corporate differences—not to mention the individual motivations of the players within the customer organizations, including decision makers, approvers, specifiers, reviewers, and others involved in shaping the company’s behavior.

Marketing has always relied on appealing to different customers in different ways. Market segmentation is a highly developed, sophisticated discipline, but it is based primarily on products and the appeal of product benefits rather than on customers and their broader set of needs considered in a holistic fashion for each individual customer. To address customers as different types of customers, rather than as recipients of a product’s different benefits, the customer-based enterprise must think beyond market segmentation per se. Rather than grouping customers into segments based on the product’s appeal, the customer-based enterprise places customers into portfolios based primarily on type of need.

A market segment is made up of customers with a similar attribute. A customer portfolio is made up of customers with similar needs. The market segmentation approach is based on appealing to the segment’s attribute, while the customer portfolio approach is based on meeting each customer’s broader need, based on the customer’s own worldview. If segments and portfolios were made up of toys, then red fire trucks might be in a segment of toys that included red checkers sets, red dolly makeup lipsticks, and red blocks. But red fire trucks would be in a portfolio of toys that included ambulances, fireboats, police cars, and maybe medical helicopters, along with fire hats and axes, stuffed Dalmatians, and ladders. A market segment might be composed of women, over age 45, with household incomes in excess of $50,000. A portfolio of customers might be made up of women who value friendships and like to entertain.

In Chapter 13, we will discuss customer management, including the grouping of customers into portfolios. There is a continuing role for traditional market segmentation, even in a highly evolved customer-strategy enterprise, because understanding how a product’s benefits match up with the attributes of different customers continues to be an important marketing activity. But as the enterprise gains greater and greater insight into the actual motivations of particular categories of customers, it will find that managing relationships cannot be accomplished in segment categories, because any single customer can easily be found in more than one segment. Instead, when they take the customer’s perspective, the managers at a customer-strategy enterprise will learn that they must meet the complex, multiple needs of each customer, as an individual. And doing this will require categorizing customers according to their own, broader needs rather than according to how they react to the product’s individually considered attributes and benefits. Each customer can appear in only one portfolio.

Understanding Needs

Understanding different customers’ different needs is critical to any serious relationship-building program. Some of the characteristics of customer needs should be given careful consideration:

- Customer needs can be situational in nature. Not only will two different consumers often buy the same product to satisfy different needs, but a customer’s needs might change from event to event, and it’s important to recognize when this occurs. An airline might think it has two customer types—business travelers and leisure travelers—but in reality this typology refers to events, not customers. Even the most frequent business traveler will occasionally be traveling for leisure, perhaps with a spouse or family instead of the usual solo travel, and in that event she will need different services from the airline than she needs when she travels on business.

- Customer needs are dynamic and can change over time as well. People are changeable creatures; our lives evolve from one stage to another, we move from place to place, we change our minds. Moreover, certain types of people change their minds more often than others, tending to be less predictable. That said, the fact that a certain type of customer is not predictable is a customer characteristic itself, which can be used to help guide an enterprise’s treatment of that customer. Marriage, new babies, and retirement typically lead to profound changes in needs for most people.

- Customers have different intensities of needs and different need profiles. Even when two customers have a similar need, one customer will have that need intensely while the other may feel the need but less intensely and perhaps in a different profile, combined with other needs. One homemaker is committed to running a very “green” kitchen, while another wants to take care of the environment where it makes sense but also has the need to save time as much as possible and may use paper plates so she doesn’t have to spend so much time washing dishes.

- Customer needs often correlate with customer value. Although it is not always true, more often than not a high-value customer is likely to have certain types of needs in common with other high-value customers. Similarly, a below-zero customer’s needs are more likely than not to be similar to other below-zero customers’ needs. A business that can correlate customer value with customer needs is generally in a good situation, because by satisfying certain types of needs, it can do a more efficient job of winning the long-term loyalty of higher-value customers.

- The most fundamental human needs are psychological. When dealing with human beings as customers (as opposed to companies or organizations), understanding the psychological differences among people can provide useful guidance for treating different customers differently.

- Some needs are shared by other customers while some needs are uniquely individual. When an online bookstore makes an automated book recommendation to an individual customer, this recommendation is based on the fact that other customers who have bought similar books as this customer has bought in the past have also bought the book being recommended now. There are hundreds of thousands of books a person could buy at an online bookstore, but people who buy similar books do so because they share similar needs. A retailer with a good database of past customer purchases can use community knowledge, purchases, and traits found in common among disparate customers, to infer which products the members of a particular community of customers might find more appealing. Software for sorting through groups of customers to find commonalities is called collaborative filtering (more about these concepts later in this chapter). However, if a florist remembers a customer’s wedding anniversary or a relative’s birthday and sends the customer a reminder, the florist is very likely to get a great deal more business, simply by remembering these unique dates for each customer. But any single customer’s wedding anniversary has very little to do with any other customer’s anniversary date. In both the bookstore’s and the florist’s case, individual customer needs are being met, but some needs are unique and personal while some are tastes or preferences that are shared by other customers, as well (see Exhibit 6.3).

- There is no single best way to differentiate customers by their needs. As difficult as it is to predict and quantify a customer’s value to the enterprise, at least the final result will be measured in economic terms. Value ranking, in other words, is done in one dimension: the financial dimension.5 But when an enterprise sets out to differentiate its customers by their needs, it is embarking on a creative expedition, with no fixed dimension of reference. There are as many ways to differentiate customers by their needs as there are creative ways to understand the deepest human motivations. The value of any particular type of needs-based differentiation is to be found solely in its usefulness for affecting the different behaviors of different customers.

- Even in B2B settings, a firm’s customers are not really another “company,” with a clearly defined, homogeneous set of needs. Instead, customers are a combination of purchasing agents, who need low prices; end users, who need benefits and attributes; the managers of the end users, who need those end users to be productive; and so on.

Exhibit 6.3 Common and Shared Needs of Customers

Community Knowledge

In the competition for a customer, the successful enterprise is the one with the most knowledge about an individual customer’s needs. In a successful Learning Relationship, the enterprise acts in the customer’s own individual interest as a result of taking the customer’s point of view. What if the customer were to maintain her own list of specifications and purchases? If the record of a customer’s consumption of groceries were maintained on her own computer rather than on a supermarket’s computer, this would undercut the competitive advantage that customization gives to an enterprise. Each week a whole cadre of supermarkets could simply “bid” on the customer’s list of grocery needs, reducing the level of competition once again to the lowest price. The customer-strategy enterprise can avoid this vulnerability, as it has devised a way to treat an individual customer based on the knowledge of that customer’s transactions as well as on the transactions of many other customers who have similarities to her. This is known as community knowledge.

Community knowledge comes from the accumulation of information about a whole community of customer tastes and preferences. It is the body of knowledge that an enterprise acquires with respect to customers who have similar tastes and needs, enabling the firm actually to anticipate what an individual customer needs, even before the customer knows he needs it. The collaborative filtering software that sorts through customers for similarities is essentially a matching engine, allowing a company to serve up products or services to a particular customer based on what other customers with similar tastes or preferences have preferred in this particular product or service.

Technology has accelerated the rate at which enterprises can apply community knowledge to better understand individual customers. This tool can help not just the individual consumers of a company like an online bookstore, but also B2B customers. The idea of community knowledge has a direct lineage from one of the most important values any B2B business can bring its own business customers: education about what other customers with similar needs are doing—in the aggregate, of course, never individually. Firms know that they must teach their customers as well as be taught by them. An enterprise brings insight to a customer based on its dealings with a large number of that customer’s own competitors. Community knowledge can yield immense benefits to many businesses, but especially to those businesses that have:

- Cost-efficient, interactive connections with customers as a matter of routine, such as online businesses, banks and financial institutions, retail stores, and B2B marketers, all of which communicate and interact with their customers directly and on a regular basis.

- Customers who are highly differentiated by their needs, including businesses that sell news and information, movies and other entertainment, books, fashion, automobiles, computers, groceries, hotel stays, and health care, among other things.

Marketing expert Fred Wiersema6 has said that there are three characteristics of market leadership: bringing out the product’s full benefits, improving the customer’s usage process, and breaking completely new ground with the customer. Any one of these types of customer education can come from the knowledge an enterprise acquires by serving other customers. An enterprise with a large number of customers can use community knowledge to lead a customer to a product or service that the enterprise knows the customer is likely to need, even though the customer may be totally unaware of this need. It might be as simple as choosing a hotel in a city the customer has never visited, but it could also apply to pursuing an appropriate investment and savings strategy, even though the customer may not have thought of it yet.

Pharmaceutical Industry Example

Consider, for example, the pharmaceutical category. Traditionally, “pharma” companies didn’t engage in much relationship building with end-user consumers (i.e., the patients for whom their drugs are prescribed). Rather, they always considered their primary customers to be the prescribing physicians and other health care providers, along with pharmacies, employers, medical insurance organizations, and the government bodies charged with overseeing the health care industry. Although pharma companies operate differently in different countries, depending on convention and regulatory regime, around the world they are now trying to become more patient-centered with their business strategies and processes. In the United States, this change has been facilitated by the Affordable Care Act (“Obamacare”), which permits consumers to have a bit more say in the kinds of medical coverage they choose, but on a global basis the move toward patient-centered thinking is being driven by the simple fact that technology now gives patients access to more information and control than ever before.

Taking a more patient-centered approach to the business, of course, has moral overtones as well. Who wouldn’t want to work for a company whose mission is to improve everyone’s health, rather than simply making as much money as possible from their patented drugs? According to Gitte Aabo, CEO of Leo Pharma, a Denmark-based company, “We strongly believe that when we focus on people, the business will follow. And that means for us as a company that there are cases where we know that we can actually meet an unmet need for the patients, but we are unable to make the business case. . . . If we are able to meet the unmet need even though we can’t make the business case, we will do it anyway.”7 But as difficult as it may be to make a strong business case for patient-centered policies, declaring patient health itself to be the company’s mission is likely to dramatically improve Leo’s ability to hire and retain highly motivated employees. Kimberly Stoddart, Vice President of Human Resources and Communications at Leo Pharma Canada, suggests, “When we are looking to hire new people, we show the video to candidates. We can tell immediately whether the concept motivates them, and to what extent, which we then explore. If it doesn’t, they’re not for us.”8

Putting patient-centric policies into practice, of course, requires the same sort of disciplines and processes that customer-centric policies require in any other industry, including needs-based differentiation of patients, whenever that will improve each patient’s experience.

One U.S. pharma company sells medicines for diabetes, which can be kept in check through constant vigilance, but as is the case with many such diseases, compliance is a constant problem. Patients often simply fail to keep up the medical treatment or they fail to monitor their own condition properly. The company knows that patients want help in understanding and dealing with the disease, so its Web site is designed to serve as a resource for patient information and support, as well as for physicians and other providers. The benefits for the pharmaceutical company and for the patient are straightforward: A better-informed and- supported patient is likely to exhibit better compliance, which will both keep the patient healthier and sell more of the pharmaceutical company’s drugs—a better, more successful patient experience, in other words, and a more profitable business as well.

Knowing that different patients will need different types of support and assistance, this pharma enterprise undertook to design a more patient-centered Web site by first conducting a research survey of patients, which revealed that a patient’s attitude toward keeping the disease in check will tend to drive her individual needs from the Web site. Newly diagnosed patients for the most part simply want any and all information related to their condition, in order to select content they feel is most relevant to their own problems. However, as patients come to grips with their sickness, their attitudes evolve, and the pharma company’s research led it to group them into three different categories:

- Individualists. This type of patient relies on herself to make educated decisions on how to manage her disease. The Web site will steer individualists toward online clinical support. They can opt in to customized electronic newsletters or take advantage of a number of online health-tracking tools and apps.

- Abdicators. This patient’s attitude toward the disease is more one of resignation and detachment. An abdicator has basically decided that she will “just have to live with the conditions of her disease,” so she ends up depending on the help given by a significant other—perhaps a spouse, a parent, or an adult child. So the site will direct abdicators to various caregiver resources, and provide planning information related to nutrition and meals.

- Connectors. This type of patient welcomes as much information and support as she can get from others to help her make educated decisions about how to manage her disease. She values the opinions of other patients with similar conditions, so the site directs connectors to online chat rooms and electronic bulletin boards, where they can meet and converse with other patients. There is an “e-buddy” feature that pairs a patient up with someone similar to herself, not just for information but for support and consolation.

For the pharmaceutical company to design a Web site that is truly customer focused, it should try to figure out, for each returning visitor, what the particular mind-set of that visitor is, and then serve up the best features and benefits for that particular type of patient. The easier the enterprise can make it for different patients to find the support and assistance they need, individually, the more valuable those patients will become for the enterprise, and vice versa.

At this juncture, however, it is important once again to separate our thinking about the features and benefits of the Web site (i.e., the product, in this case) from the actual psychological needs and predispositions of the Web site visitors themselves. Any one of the visitors might in fact use any of the Web site’s many features on any particular visit. That means each of the Web site’s benefits will probably overlap several different types of customers, with different types of needs. But the customers themselves do not overlap—they are unique individuals with their own unique psychology and motivation. It is only our categorization of these unique and different customers into needs-based groups that might give us the illusion that they are the same. They may be similar in their needs, but at a deeper level, they are still uniquely individual, and this will be true no matter how many additional categories, or portfolios, we create. We simply categorize customers in order to better comprehend their differences by making generalizations about them.

Gary Adamson, who served as past president of Medimetrix/Unison Marketing in Denver, Colorado, said the power of health care integration lies in creating the ability to do things differently for each customer, not to do more of the same for all customers.9 One of Medimetrix’s clients, Community Hospitals in Indianapolis, Indiana, for example, implemented “Patient-Focused Medicine,” a customer relationship management (CRM) initiative aimed at four constituent groups: patients, physicians, employees, and payers. The hospital has found that most medical practitioners customize the “care for you” component of health care by individually diagnosing and treating medical disorders. But Community also individualizes the “care about you” component—the part that makes most patients at most hospitals feel like one in a herd of cattle.

The real opportunity lies in building a Learning Relationship between the health care provider and the customer. A drugstore, for example, might know a customer buys the same over-the-counter remedy every month. But if the same drugstore detects that the customer is suddenly buying the product every week, it could personalize its service by asking her whether she is having a health problem and how it could assist her with personal information or other types of medication. Already, the pharmacy is the last resort for many patients to help spot possible drug interactions for prescription and over-the-counter drugs prescribed and recommended by a variety of different physicians. Using information to serve the customer better helps the drugstore create a long-lasting bond with this customer.

Using Needs Differentiation to Build Customer Value

The scenarios of the toy manufacturer and the pharmaceutical company show how each had to be aware of its respective individual customer’s needs so it could act on them. Once a particular customer’s needs are known, the company is better able to put itself in the place of the customer and can offer the treatment that is best for that customer. Each company gets the information about customer needs primarily by interacting. Therefore, an open dialogue between the customer and the enterprise is critical for needs differentiation. Moreover, customer needs are complex and intricate enough that the more a customer interacts with an enterprise, the more learning an enterprise will gain about the particular preferences, desires, wants, and whims of that customer. Provided that the enterprise has the capability required to act on this more and more detailed customer insight, by treating the customer differently, it will be able to create a rich and enduring Learning Relationship.

A successful Learning Relationship with a customer is founded on changes in the enterprise’s behavior toward the customer based on the use of more in-depth knowledge about that particular customer. Knowing the individual customer’s needs is essential to nurturing the Learning Relationship. As the firm learns more about a customer, it compiles a gold mine of data that should, within the bounds of privacy protection, be made available to all those at the enterprise who interact with the customer. Kraft, for example, empowers its salespeople with the data they need to make intelligent recommendations to a retailer. (The retailer is Kraft’s most direct customer, and the retailer sells Kraft products to end-user consumers, who can also be considered Kraft’s customers.) Kraft has assembled a centralized information system that integrates data from three internal database sources. One database contains information about the individual stores that track purchases of consumers by category and price. Another database contains consumer demographics and buying-habit information at food stores nationwide. A third database, purchased from an outside vendor, has geodemographic data aligned by zip code.

But truly to get to know a consumer through interactions directly with her, enterprises must do more than gather and analyze aggregated quantitative information. Accumulating information is only a first step in creating the knowledge needed to pursue a customer-centered strategy successfully. Information is the raw material that is transformed into knowledge through its organization, analysis, and understanding. This knowledge then must be applied and managed in ways that best support investment decisions and resource deployment.

Customer knowledge management is the effective leverage of information and experience in the acquisition, development, and retention of a profitable customer. Gathering superior customer knowledge without codifying and leveraging it across the enterprise results in missed opportunities.10

Summary

We have now discussed the necessity of knowing who the customer is (identifying) and knowing how the customer is different individually (valuation and needs, often indicated by behavior). Getting this information implies that the enterprise will need to interact with each customer to understand each one better. Once the enterprise has ranked customers by their value to the enterprise and differentiated them based on their needs, it conducts an ongoing, collaborative dialogue with each customer. This interaction helps the enterprise to learn more about the customer, as the customer provides feedback about her needs. The enterprise can then use the customer’s feedback to modify its service and products to meet her needs (i.e., to “customize” some aspect of the customer’s treatment to the needs of that particular customer).

The “identify” and “differentiate” steps in the Identify-Differentiate-Interact- Customize (IDIC) taxonomy for developing and managing customer relationships can be accomplished by an enterprise largely with no actual participation by the customer. That is, a customer won’t necessarily have to know or involve herself in the process that the enterprise uses to identify her, as a customer, or to rank her by value, or even to evaluate her needs, as a customer. These first two steps—“identify” and “differentiate”—can be thought of as the “customer insight” phase of relationship management. However, the third step—”interact”—requires the customer’s participation. Interaction and customization can only really take place with the customer’s direct involvement. These latter two steps could be thought of as managing the “customer experience,” based on the insight developed.

Interacting with customers, the third step in the IDIC taxonomy, is our next point of discussion.

Food for Thought

- Why has more progress been made on customer value differentiation than on customer needs differentiation?

- If it could only do one, is it more likely that a customer-oriented company would rank all of its customers differentiated by value or differentiate all of its customers by need?

- Is it possible to meet individual needs? Is it feasible? Describe three examples where doing this has been profitable.

- For each of the listed product categories, name a branded example, then hypothesize about how you might categorize customers by their different needs, in the same way our sample toy company and pharmaceutical company did. Unless noted for you, you can choose whether the brand is business to consumer (B2C) or B2B:

- Automobiles (consumer)

- Automobiles (B2B, i.e., fleet usage)

- Air transportation

- Cosmetics

- Computer software (B2B)

- Pet food

- Refrigerators

- Pneumatic valves

- Hotel rooms

Glossary

- Attributes

- Physical features of the product.

- Benefits

- Advantages that customers get from using the product. Not to be confused with needs, as different customers will get different advantages from the same product.

- Collaborative filtering

- Software designed to sort through groups of customers to find commonalities among different customers.

- Commoditization

- The steady erosion in unique selling propositions and unduplicated product features that comes about inevitably, as competitors seek to improve their offerings and end up imitating the more successful features and benefits.

- Community knowledge

- The body of customer data that shows what different customers have in common among themselves, including purchases, behaviors, and traits. Collaborative filtering is software for mining this community knowledge.

- Customer portfolio

- A group of similar customers. The customer-focused enterprise will design different treatments for different portfolios of customers.

- Customer relationship management (CRM)

- As a term, CRM can refer either to the activities and processes a company must engage in to manage individual relationships with its customers (as explored extensively in this textbook), or to the suite of software, data, and analytics tools required to carry out those activities and processes more cost efficiently.

- Customer-strategy enterprise

- An organization that builds its business model around increasing the value of the customer base. This term applies to companies that may be product oriented, operations focused, or customer intimate.

- Customization

- Most often, customization and mass customization refer to the modularized building of an offering to a customer based on that customer’s individual feedback, thus serving as the basis of a Learning Relationship. Note the distinction from personalization, which generally simply means putting someone’s name on the product.

- Customize

- Become relevant by doing something for a customer that no competition can do that doesn’t have all the information about that customer that you do.

- Differentiate

- Prioritize by value; understand different needs. Identify, recognize, link, remember.

- Expanded need set

- The capability of a company to think of a product it sells as a suite of product plus service plus communication as well as the next product and service the need for the original product implies. The sale of a faucet implies the need for the installation of that faucet, and maybe an entire bathroom upgrade and strong nesting instinct.

- Identify

- Recognize and remember each customer regardless of the channel by or geographic area in which the customer leaves information about himself. To be able to link information about each customer to generate a complete picture of each customer.

- Lifetime value (LTV)

- Synonymous with “actual value.” The net present value of the future financial contributions attributable to a customer, behaving as we expect her to behave—knowing what we know now, and with no different actions on our part.

- Market segment

- A group of customers who share a common attribute. Product benefits are targeted to the market segments thought most likely to desire the benefit.

- Mass customization

- See Customization.

- Needs

- What a customer needs from an enterprise is, by our definition, synonymous with what she wants, prefers, or would like. In this sense, we do not distinguish a customer’s needs from her wants. For that matter, we do not distinguish needs from preferences, wishes, desires, or whims. Each of these terms might imply some nuance of need—perhaps the intensity of the need or the permanence of it—but in each case we are still talking, generically, about the customer’s needs.

- Recognition

- See also Identify.

- Sales force automation (SFA)

- Connecting the sales force to headquarters and to each other through computer portability, contact management, ordering software, and other mechanisms.

- Share of customer

- For a customer-focused enterprise, share of customer is a conceptual metric designed to show what proportion of a customer’s overall need is being met by the enterprise. It is not the same as “share of wallet,” which refers to the specific share of a customer’s spending in a particular product or service category. If, for instance, a family owns two cars, and one of them is your car company’s brand, then you have a 50 percent share of wallet with this customer, in the car category. But by offering maintenance and repairs, insurance, financing, and perhaps even driver training or trip planning, you can substantially increase your share of customer.

- Social networking

- The ability of individuals to connect instantly with each other often and easily online in groups. For business, it’s about using technology to initiate and develop relationships into connected groups (networks), usually forming around a specific goal or interest.

- Unrealized potential value

- The difference between a customer’s potential value and a customer’s actual value (i.e., the customer’s lifetime value).

- Value skew

- The distribution of lifetime values by customer ranges from high to low. For some companies, this distribution shows that it takes a fairly large percentage of customers to account for the bulk of the company’s total worth. Such a company would have a shallow value skew. Another company, at which a tiny percentage of customers’ accounts for a very large part of the company’s total value, can be described as having a steep value skew.