Chapter 13

Organizing and Managing the Profitable Customer-Strategy Enterprise, Part 1

Work is of two kinds: first, altering the position of matter at or near the earth’s surface relative to other matter; second, telling other people to do so.

—Bertrand Russell

If we can measure it, we can manage it. Now that we have become better at the metrics of customer valuation and equity, can we hold someone responsible for increasing the value of customers and keeping them longer? Most companies have brand managers, product managers, store managers, plant managers, finance managers, customer interaction center managers, Web masters, regional sales managers, branch managers, and/or merchandise managers. These days, even beyond the obvious high-end personal and business services, more and more companies have customer relationship managers. Now that technology drives a dimension of competition based on keeping and growing customers, the questions to ask are:

- Who will be responsible for the enterprise’s relationship with each customer? For keeping and growing each customer? For building the short-term revenues and long-term equity and value of each customer?

- What authority will that customer manager need to have in order to change how the enterprise treats “her” customers, individually?

- How will she use tools and technology to create better experiences for her customers?

- What will she have to do?

- By what criteria and metrics will success be measured, reported, and used for compensation?

In this chapter, we ask the questions: How will executives at the enterprise develop management skills to increase the value of the customer base? How will our information about customers—and our goal to build the value of the customer base—inform every business decision we make all day, every day?

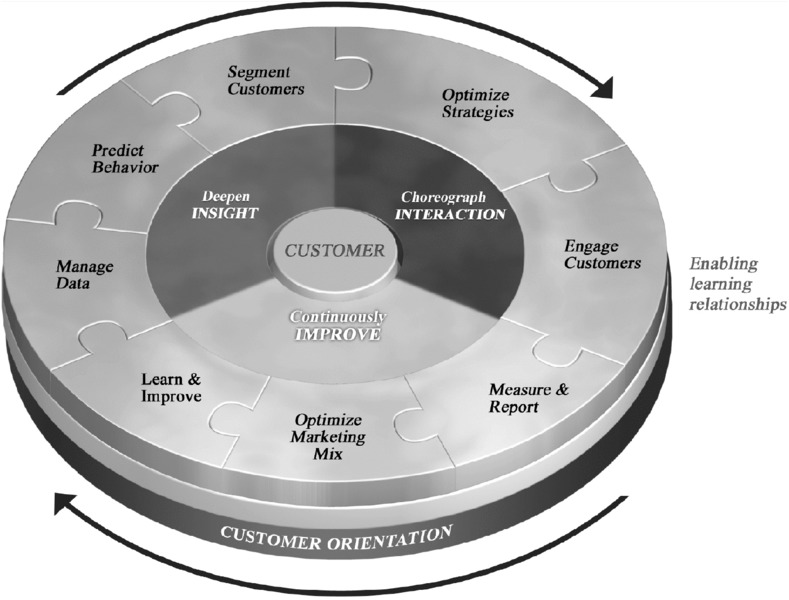

We have shown that in the customer-strategy enterprise, the goal is to maximize the value of the customer base by retaining profitable customers and growing them into bigger customers; by eliminating unprofitable customers or converting them into profitable relationships; and by acquiring new customers selectively, based on their likelihood of developing into high-value customers. The overriding strategy for achieving this set of objectives is to develop Learning Relationships, built on trust, with individual customers, in the process customizing the mix of products, prices, services, and/or communications for each individual customer, wherever practical.

It should be apparent that the new enterprise must be organized around its customers rather than just its products. Success requires that the entire organization reengineer its processes to focus on the customer.1 In this chapter, we examine the basics of management at a customer-strategy enterprise. Our goal is to understand the capabilities necessary to create and manage a successful customer-strategy company. We draw a picture of what the organizational chart looks like and explain how to make the transition, overcome obstacles, and build momentum. We also have a look at the role of employees in the customer-strategy enterprise.

Before any of that, though, let’s look at what it means to manage customer experiences—what they are and how to make them better.

Now let’s take a look at what some of the experts say about how to fix experiences—by fixing service.

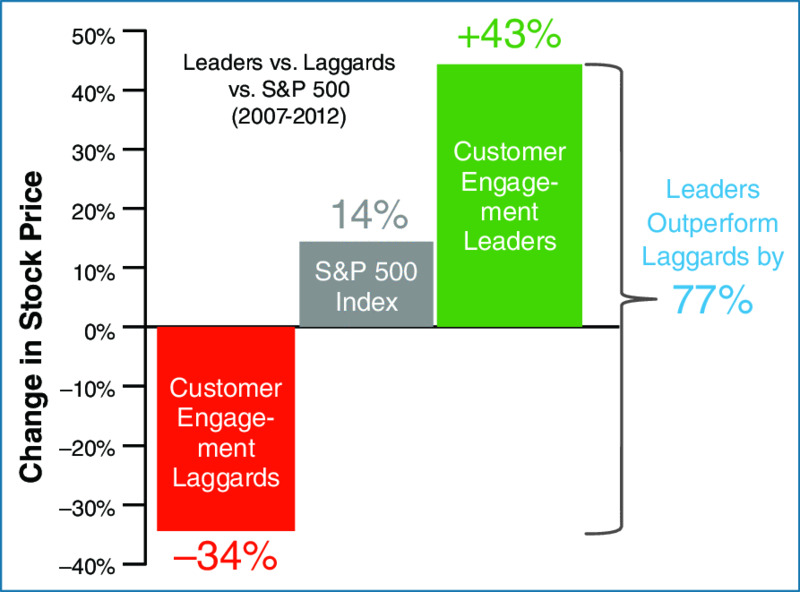

Exhibit 13.1 U.S. Customer Experience Leaders vs. Laggards vs. S&P 500, 2007–2012

Source: Watermark Consulting.

When you do need customer service, high-quality customer service is one of the beneficial outcomes of adopting customer strategies. Enterprises must keep in mind the cost of not providing sufficient service, thereby risking the loss of customers, the cost of lost long-term customer equity, and the expensive task of acquiring new customers. General wisdom places the estimate for customer defections due to a poor sales or service interaction between the customer and the enterprise at about 70 percent. It isn’t necessary for a company to make formal Return on Customer (ROC) calculations to understand that the short-term losses in revenue and long-term customer equity cost to shareholders of poor service far outweigh the current perceived “savings” of reducing service quality.

Moreover, an enterprise must balance the cost of providing customer service with the needs and desires of the customer in such a way that the customer will find sufficient value in the enterprise to remain a customer. At a minimum, certain standards of accuracy, timeliness, and convenience must be in place to placate most customers. The right technology and processes must first be deployed, followed by the training and adoption of service practices by customer-facing representatives.

But what is the “right amount” of customer service? What do customers actually need and want? Are we doing the same expensive things for everybody when our most valuable customers would be even happier with less expensive service (think mobile or online banking versus service counter at the bank branch)? Taking different customer needs into consideration, what is the least expensive amount for the enterprise to spend on service that works for the customer? Which channel do customers want to use? Can they be easily moved to one that costs less—especially customers with low actual value and potential value? And should different levels of service be offered to different kinds of customers? Might customer service mean different things to different customers? When is self-service appropriate? Certainly these and other questions should be addressed if an enterprise is to find the balance of service that serves both the customer and the budget. Some companies still look at customer service as a cost center, but others see it as building customer equity, and opportunity. The difference is palpable in the resulting customer experience. Art Schoeller describes the general problem: Enterprises “constantly seeking to offload more expensive agent-assisted interactions to self-service” for cost savings may seem to dovetail with consumers increasingly seeking and relying on self-service with digital devices, but “many organizations provide a disappointing customer experience, with 57 percent of U.S. online consumers reporting they have had unsatisfactory service interactions in the past 12 months.”2 The solution is finding the right balance for the customer and matching service and mode to the consumer need at the moment.

Schoeller continues: “While consumers hop channels to research products and services, there usually is a moment of truth when an informed agent can make the right offer and close the sale. Companies that capture consumer interaction data from web and mobile self-service touch points can more effectively match the right agents with prospects.”

In another example, United Airlines developed a mobile app designed around the stress points of travel day. Flight updates, rebookings, food options, and self-check-in were all set up to give customers a sense of control when they most need reassurance. In mid-2012, 1.5 million passengers had downloaded the app. Nine months later, usage levels reached 6 million. By June 2014, users totaled 10 million. It’s obvious that this is self-service that has been of value to customers, but as significantly, the app also led to major cost savings to the company as staffing at United counters fell by half.3

Is “good” customer service in the eyes of the beholder? Some criteria an enterprise could consider from the customer’s perspective include:

- Saving time or money

- Accuracy of a transaction

- Speed of service

- Ease of doing business

- Providing better (not just more) information

- Recording and remembering relevant data

- Convenience

- Allowing a choice of ways to do business

- Treating customers as individuals

- Acknowledging and remembering the relationship

- Fixing problems quickly

- Thanking the customer

Not all of these elements are equally important to all customers. Any one of these criteria could be a deal breaker to one customer and of no consequence to another. Adding or upgrading customer services uniformly for everyone is an expensive way to raise the bar. Better to know what’s important to an individual customer and then to make sure that customer gets the services most important to him.

Many enterprises have learned that the integration of the contact center with all other communication vehicles may be the first step toward successful completion of the customer’s mission. For example, live online customer service, text-based chat, and Web callbacks are some of the vehicles that can elevate good, basic customer service to excellent and highly satisfactory service, the latter of which translates into customer retention, growth, loyalty, and profitability.

In the next section, Chris Zane, named a Customer Champion by 1to1 Media, explains how his whole business focuses on customer experiences and service.

At many firms, the “customer service” function is thought of as a cost of doing business rather than as an integral part of the products or services actually being sold to customers. It is easy to spot an enterprise with this attitude. This is the company that hides its toll-free number on the Web site and that has an impenetrable interactive voice response (IVR) system (see Chapter 7).

Increasingly, customer transactions are moving to an e-commerce model, and transactions normally handled with a phone call are now being done electronically, via the Web site. In many customer service areas, this has changed the mix of calls that are handled by the customer service rep. “Easy” transaction (order-taking) calls are now being replaced with more difficult customer situation calls (complaints, inquiries, billing and invoicing questions, etc.). This can increase the level of stress experienced by the customer service reps.

Traditional measures for customer interaction centers have focused on “talk time” and “one and done” measures. (See a more complete discussion about the customer interaction center in Chapter 7.) As we dig deeper into customer metrics, we start measuring average talk time for valuable customers versus customers who call into the customer interaction center frequently and yet do not generate enough revenue to warrant high levels of service. We begin to understand which customers are buying a wide range of products and services offered by an enterprise and which customers should be but aren’t. Many customer interaction center managers are left to fight a battle to increase talk time for the customers who warrant more attention, but they lack the analytics and resulting insights (“the facts”) to be able to justify that decision. This is where partnering with the customer manager is key: the justification for these measures should be in the customer strategies.

The fact is, however, that a customer-strategy company often can keep its costs down by centering on customer needs. Calls are more often resolved in one session and in less total time. Customer service reps do not “chase down” information or transfer customers from department to department. Voice response unit options are reordered to present the most likely option desired by that customer as soon as the customer is identified. This process can significantly decrease phone costs for an enterprise maintaining a toll-free phone line. And it requires that people within the enterprise start thinking like customers, or taking the customer’s point of view during key interactions (such as a sales call or customer care call), and combine this point of view with the customer strategy and business rules that have been identified for this customer. Change often demands new skill sets. As the enterprise begins to define specific roles and responsibilities (or job descriptions) for various customer care representatives, it also will need to develop training and development plans and recruitment and staffing plans. These descriptions include competencies and behaviors that will be required of all employees—things like customer empathy—and skills associated with different roles. Employees might determine how they “touch” the customer directly or indirectly by supporting another department.

An often-neglected step in this process is planning around the way customer care representatives are supported, measured, and compensated to reinforce the new behaviors, which should incorporate the customer-centered metrics described earlier. Unfortunately, the reporting capabilities in many enterprises are not up to the task, and some great customer-oriented efforts have gone awry because this last step was not implemented. Employees often want to “do the right thing” but are not supported or measured adequately or correctly. More important, many companies equate customer relationship management with “customer service,” when in fact customer service—important as it is—is not the same as relationships, customer experience management, or customer equity building. The heart of a Learning Relationship is a memory of a customer’s expressed needs so that this customer can be treated in a way that works for him without his having to be asked again, and so a dialogue can pick up right where it left off. Customer service, in contrast, is often more like random acts of kindness masquerading as customer relationship management.

Relationship Governance

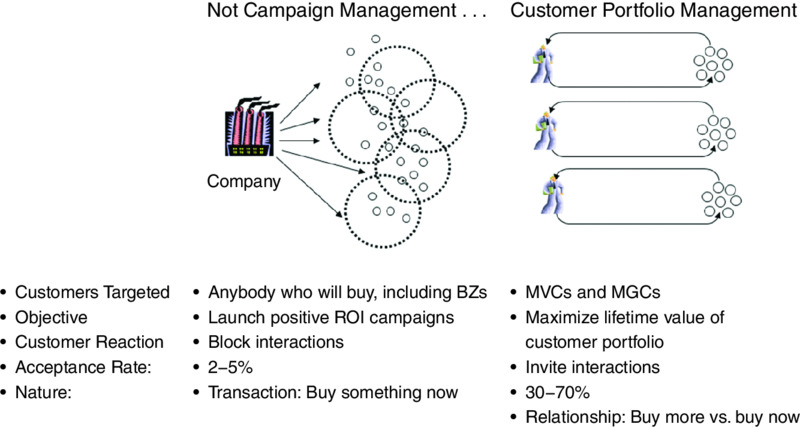

One of the biggest single difficulties in making the transition to an enterprise that pays attention to its relationships with individual customers and creating better experiences for them is the issue of relationship governance. By that we mean: Who will be “in charge” at the enterprise when it comes to making different decisions for different customers? Optimizing around each customer, rather than optimizing around each product or channel, requires decision making related to customer-specific criteria, across all different channels and product lines. When Customer A is on the Web site or on the phone, the enterprise wants to ensure that the very best, most profitable offer is presented for that customer. The firm’s call center shouldn’t try to compete with its own stores to try to get the customer to buy from them, nor should the product manager for Product 1 compete with the product manager for Product 2 and try to win the customer for one product line or another. What the customer-centric enterprise wants is to deliver whatever offer for this customer is likely to create the most value, overall, for the company and the customer without regard to any other organizational or department goals or incentives that might have been established at the firm. This, in a nutshell, is the problem of relationship governance. The challenge most companies face when they make a serious commitment to managing customer relationships becomes obvious once the firm pulls out its current organizational charts, which usually are set up to manage brands, products, channels, and programs. Most companies have organized themselves in such a way as to ensure that they can achieve their objectives in terms of product sales or brand awareness across the entire population of customers they serve.

But in the age of interactivity, managing customer relationships individually will require an enterprise to treat different customers differently within that customer population. Inherent in this idea is the notion that different customers will be subject to different objectives and strategies and that the enterprise will undertake different actions with respect to different customers. So we ask again: With respect to any particular customer, who will be put in charge, and held accountable, within the enterprise, to make sure this actually happens? And when that person is put in charge of an individual customer relationship, what levers will he control in order to execute the strategy being applied to “his” customer? How will his performance be measured and evaluated by the enterprise, for the current period as well as the long term? (Recall the Canadian bank example we cited in Chapter 11, a company where customer portfolio managers are measured in the current quarter for the current revenue by the bank of the customers in their portfolios and for the three-year projected value, as of today, of that same group of customers.)

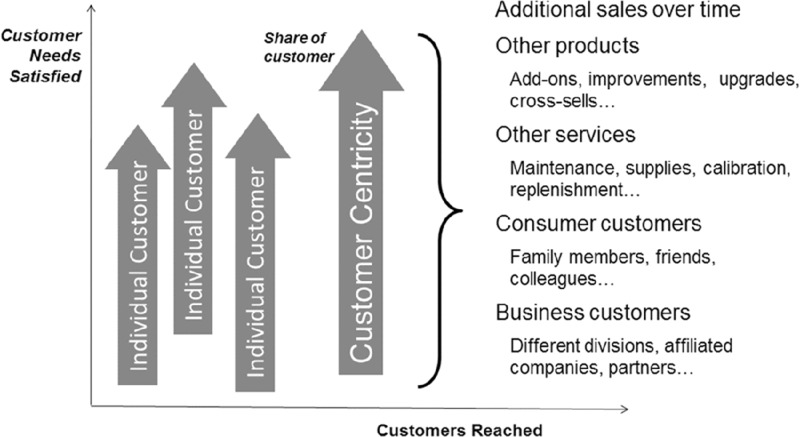

This is the problem of relationship governance. It’s one thing for us to maintain, safe between the covers of this book, that in the interactive age a company should manage its dialogues and relationships with different customers differently, making sure to analyze the values and needs of various individual customers, adapting its behavior for each one to what is appropriate for that particular customer. It’s another thing to carry this out within a corporate organization when, at least for many companies at present, no one is actually in charge of making it happen. In the first chapter of this book, we showed the orthogonal relationship of customer orientation and product orientation: finding customers for products or products for customers. We can extend this customer orientation thinking in the way it’s shown in Exhibit 13.2.

Exhibit 13.2 Share of Customer = Share of Need

The customer-oriented company will focus on one customer at a time and try to find the next right offer, service, and/or product for that customer. And another one and another one, winning a greater and greater share of each customer’s business by generating top-notch customer experiences and building Learning Relationships. But how is a company structured to accomplish this mission?

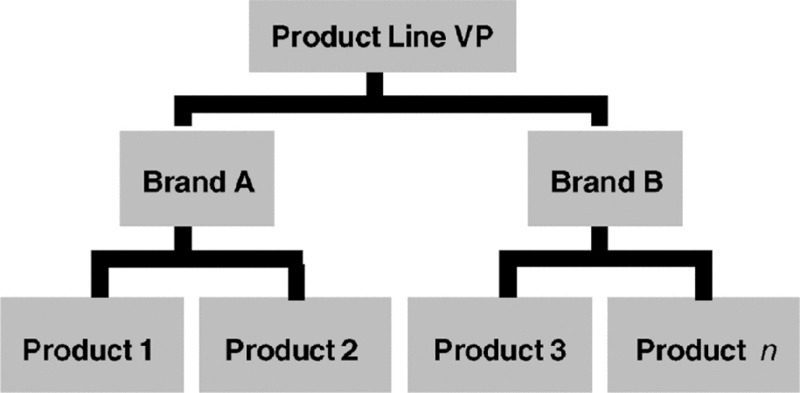

Exhibit 13.3 is an oversimplified example of a “typical” old Industrial Age organization chart. In such an organization, each product or brand is the direct-line responsibility of one individual within the organization. In this way, the enterprise can hold particular managers and organizations responsible for achieving various objectives related to product and brand sales. The brand or product manager is, in fact, the “protector” of the brand or product, watching out to make sure that it does well and that sales goals or awareness goals are achieved. The manager controls advertising and promotion levers to ensure that the best and most persuasive message will be conveyed to the right segments and niches of customers or potential customers. This is all in keeping with the most basic goal of an old-fashioned Industrial Age company: to sell more products to whoever will buy them.

Exhibit 13.3 Product Management Organization

The most basic goal of the customer-strategy enterprise, however, is to increase the long-term value of its customer base, by applying different objectives and strategies to different customers. Yes, in the process it’s practically certain that more products will be sold in the short term. But in order for the primary task to be accomplished, someone within the organization has to be put in charge of making decisions and carrying out actions with respect to each individual customer, even if that task is completely automated.

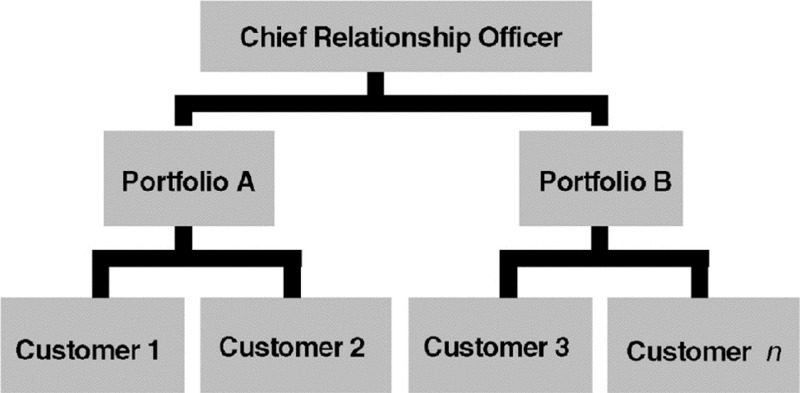

In Exhibit 13.4, a different organization chart is drawn for the customer-value-building company, one that emphasizes customer management rather than product management. In an enterprise organized for customer management, ideally every customer will be the direct-line responsibility of a single customer manager (even though the customer may not be aware that the manager is in charge, as he works in the background to determine the enterprise’s most appropriate strategy for that customer and then to make sure it is carried out). Because there are likely many more customers than there are management employees, it is only logical that a customer manager should be made responsible for a whole group of customers. We refer to such a group as a customer portfolio, avoiding for the present the phrase customer segment, in order to clarify the concept.

Exhibit 13.4 Customer Management Organization

A customer portfolio is made up of unduplicated, unique (and identified) customers. No customer will ever be placed into more than one portfolio at a time, because it is the portfolio manager who will be in charge of the enterprise’s relationship with the customers in her portfolio and the resulting value of that relationship.

If we allow a customer to inhabit two different portfolios, then we are just creating another relationship governance problem—which portfolio manager will actually call the shots when it comes to the enterprise’s strategies for that customer? How will we calculate that customer’s value accurately? And who gets credit or blame if the customer’s value rises or falls?

A customer manager’s primary objective is to maximize the long-term value of his own customer portfolio (i.e., to keep and grow the customers in his portfolio), and the enterprise should reward him based on a set of metrics that indicate the degree to which he has accomplished his mission. In the ideal state, the enterprise’s entire customer base might be parsed into several different portfolios, each of which is overseen by the customer manager, like a subdivided business that creates value in the long term and the short term as of today. (See Exhibit 13.5.)

Exhibit 13.5 Managing Customer Portfolios for the Long Term

Clearly, if we plan to hold a customer manager accountable for growing the value of a portfolio of customers, then we’ll also have to give her some authority to take actions with respect to the customers in the portfolio. The levers that a customer manager ought to be able to pull, in order to encourage her customers to attain a higher and higher long-term value to the enterprise, should include, literally, every type of action or communication that the enterprise is capable of rendering on an individual-customer basis. In communication, this would mean that the customer manager would control the enterprise’s addressable forms of communication and interaction: direct mail as well as interactions at the call center, on the Web site, ads displayed on the customer’s screen when he’s visiting another Web site, on his mobile device, and even (to the extent possible) in face-to-face encounters at the store or the cash register. In effect, the customer manager would be responsible for overseeing the enterprise’s continuing dialogue with a customer. In terms of the actual product or service offering, ideally the customer manager would be responsible for setting the pricing for her customers, extending any discounts or collecting premiums, and so forth. The customer manager should own the offer,4 and the communication of the offer, with respect to the customers in the manager’s portfolio.

The enterprise will still be creating and marketing various programs and products, but the customer manager will be the “traffic cop,” with respect to his own portfolio of customers. He will allow some offers to go through as conceived, he will adapt other offers to meet the needs of his own customers, and he will likely block some offers altogether, choosing not to expose his own customers to them.

In a high-end business or personal services firm, such as a private bank, the role of customer manager is played by the firm’s relationship manager for each client. The relationship manager owns the relationship and is free to set the policies and communications for her own individual clients, within the boundaries set by the enterprise. The enterprise holds her accountable for keeping the client satisfied, loyal, and profitable. The company probably does not formally estimate an individual client’s actual LTV, in strict financial terms; more than likely it has a fairly formal process for ranking these clients by their long-term value or importance to the firm. A relationship manager who manages to dramatically improve the value of her client’s relationship to the enterprise will be rewarded.

However, most businesses have many more customers than a private bank, or a law firm, or an advertising agency. For most businesses, it would simply be uneconomic for a relationship manager to pay individual, personal attention to a single customer relationship, to the exclusion of all other responsibilities. Realistically, then, the way most of the addressable communications will be rendered to individual customers, at the vast majority of companies, will be through the application of business rules. Just as business rules are used to mass-customize a product or a service (see Chapter 10), they can be applied to mass-customize the offer extended to different customers as well as the communication of that offer. Thus, one of the customer manager’s primary jobs will be to oversee the business rules that govern the enterprise’s mass-customized relationship with the individual customers in his own portfolio.

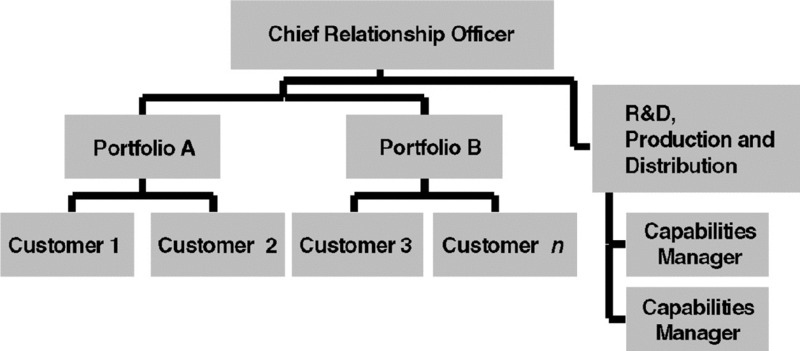

In addition to customer relationship managers, the one-to-one enterprise will need capabilities managers as well (see Exhibit 13.6).5 Their role is to deliver the capabilities of the enterprise to the customer managers, in essence figuring out whether the firm should build, buy, or partner to render any new products or services that customers might require. We could think of capabilities managers as being something like product managers at large. The products and capabilities they bring to bear, on behalf of the enterprise, actually will not necessarily be marketed to customers but very likely instead to the customer managers in charge of the enterprise’s relationships with customers.

Exhibit 13.6 Product Managers Become Capabilities Managers

None of this is to say that companies can afford to forget about product quality, or innovation, or efficient production and cost reduction. These tasks will be just as important as they always have been, for the simple reason that few customers would choose to continue relationships involving subpar products or service. However, as we’ve already discussed, product and service quality by themselves do not necessarily lead to competitive success, because no matter how stellar a company’s service is, nothing can stop a competitor from also offering great service—or a great, breakthrough product, or a low price. In the final analysis, the most important single benefit of engaging a customer in an ongoing relationship is that the rich context of a Learning Relationship creates an impregnable competitive barrier, with respect to that customer, making it literally impossible for a competitor to duplicate the customer experience the customer is now receiving.

In order to track whether the effect of what we’re doing for customers is or is not working, more and more companies are engaged in customer experience journey mapping. The journey mapping tracks what it’s like to be our customer now, visualizes what it should be like, and sets up the plan to close the gap. Valerie Peck, cofounder and CEO of SuiteCX, a journey mapping tool, tells us what mapping is and does, and how to do it.6

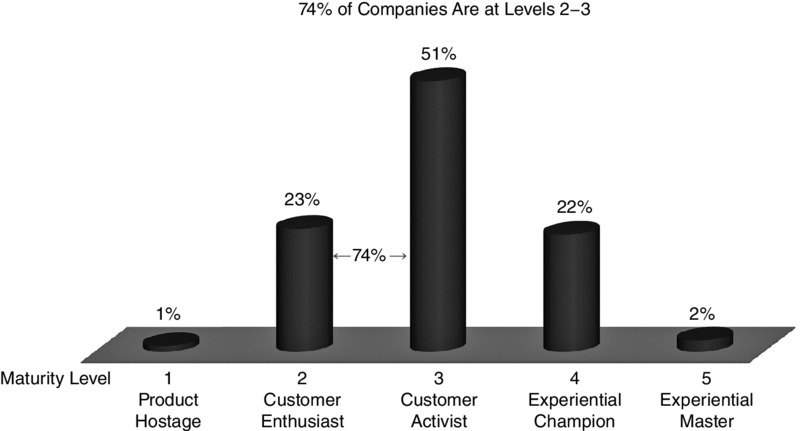

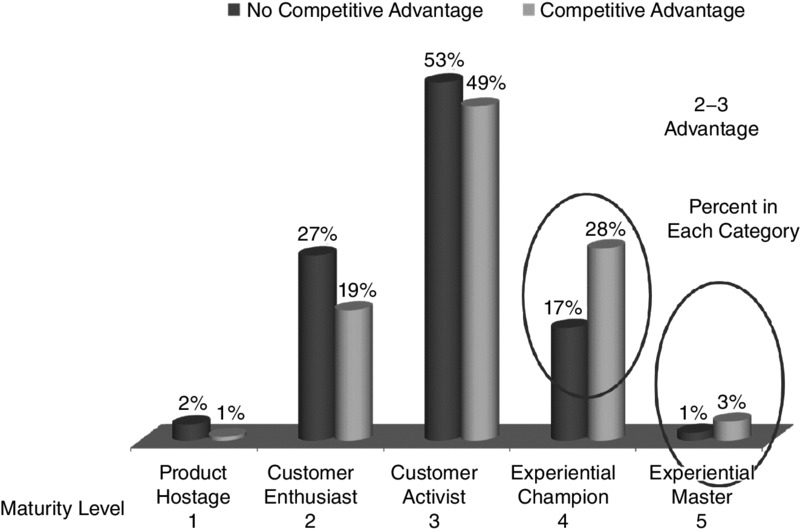

One of the most important questions executives can ask is whether better customer experiences and relationships will pay off for a company. In a seminal study, Jeff Gilleland and his colleagues asked that question. Essentially, they compared how far along on the customer-orientation journey companies were, and compared the performance levels of companies at high and low levels. Here’s what they discovered.

Exhibit 13.7 CEMM Measured Customer Orientation and 3-I Capabilities

Exhibit 13.8 Customer Experience Maturity Continuum

Exhibit 13.9 Competitive Advantage Accrues with CEM Maturity

Summary

Now that we’ve described the larger-scale processes needed to transition from a product-centric to a customer-centric enterprise, we need to get specific: What needs to be done throughout the organization to make this transition? Part 2 of our discussion of managing the customer-centric enterprise in Chapter 14 covers just that.

Food for Thought

- Choose an organization and draw its organizational chart. How would that chart have to change in order to facilitate customer management and to make sure people are empowered, evaluated, measured, and compensated for building the value of the customer base? Consider these questions:

- If a customer’s value is measured across more than one division, is one person placed in charge of that customer relationship?

- Should the enterprise establish a key account-selling system?

- Should the enterprise underwrite a more comprehensive information system, standardizing customer data across each division?

- Should the sales force be better automated? Who should set the strategy for how a sales rep interacts with a particular customer?

- Is it possible for the various Web sites and call centers operated by the company to work together better?

- Should the company package more services with the products it sells, and if so, how should those services be delivered?7

- For the same organization, consider the current culture, and describe it. Would that have to change for the organization to manage the relationship with and value of one customer at a time? If so, how?

- At the same organization, assume the company rank-orders customers by value and places the most valuable customers behind a picket fence for 1to1 treatment. What happens to customers and to customer portfolio managers behind that picket fence?

- In an organization, who should “own” the customer relationship? What does that mean?

- What are the best ways to compensate and reward customer managers?

Glossary

- Actual value

-

The net present value of the future financial contributions attributable to a customer, behaving as we expect her to behave—knowing what we know now, and with no different actions on our part.

- Addressable

-

Refers to media that can send and customize messages individually.

- Business model

-

How a company builds economic value.

- Business process reengineering (BPR)

-

Focuses on reducing the time it takes to complete an interaction or a process and on reducing the cost of completing it. BPR usually involves introducing quality controls to ensure time and cost efficiencies are achieved.

- Business rules

-

The instructions that an enterprise follows in configuring different processes for different customers, allowing the company to mass-customize its interactions with its customers.

- Capabilities manager

-

The person at an enterprise charged with delivering the capabilities of the enterprise to the customer managers, in essence figuring out whether the firm should build, buy, or partner to render any new products or services that customers might require. Customer managers “represent” their own customers’ interests within an enterprise, while capabilities managers have the authority and responsibility for meeting the demands placed on the enterprise by the customer managers.

- Customer centricity

-

A “specific approach to doing business that focuses on the customer. Customer/client centric businesses ensure that the customer is at the center of a business philosophy, operations or ideas. These businesses believe that their customers/clients are the only reason they exist and use every means at their disposal to keep the customer/client happy and satisfied.”8 At the core of customer centricity is the understanding that customer profitability is at least as important as product profitability.

- Customer equity (CE)

-

The sum of all the lifetime values (LTVs) of an enterprise’s current and future customers, or the total value of the enterprise’s customer relationships. A customer-centric company would view customer equity as its principal corporate asset. See also the definition of customer equity in Chapter 1.

- Customer experience

-

The totality of a customer’s individual interactions with a brand, over time.

- Customer experience management (CEM)

-

The integrated process of designing an experience for each customer based on knowledge of that customer, delivering it across products and channels, and measuring individual outcomes that enable improvement of future interactions. The goal of CEM is to create Learning Relationships with customers, thereby building customer equity and shareholder value over the long term.

- Customer interaction center

-

Where all calls are handled, regardless of type, for a certain customer segment or customer portfolio.

- Customer journey mapping

-

A process of diagramming all the steps a customer takes when engaging with a company to buy, use, or service its product or offering. Also called customer experience journey mapping.

- Customer manager

-

A customer manager is the person at an enterprise who is “in charge” of particular customer relationships. The customer manager’s objective is to increase the value of the customers in his or her charge, and the authority required to do this should include responsibility for every type of individually specific action or communication that the enterprise is capable of rendering to the customer. In communication, this would mean that the customer manager would control the enterprise’s addressable forms of communication and interaction, with respect to his or her specific customers.

- Customer orientation

-

An attitude or mind-set that attempts to take the customer’s perspective when making business decisions or implementing policies.

- Customer portfolio

-

A grouping of customers based on value and understood by the needs they have in common as well as the needs they have individually expressed by their interactions and transactions through various touch points over time. In contrast to grouping customers by segments, where customers are treated as look-alikes within the segment (meaning that segment marketing is really mass marketing, only smaller), the customer-strategy enterprise will work to manage portfolios of individual customers.

- Customer relationship management (CRM)

-

As a term, CRM can refer either to the activities and processes a company must engage in to manage individual relationships with its customers (as explored extensively in this textbook), or to the suite of software, data, and analytics tools required to carry out those activities and processes more cost efficiently.

- Customer segment

-

A group of customers who are suited for the same or similar marketing initiatives because of particular qualities or characteristics they have in common.

- Customer service

-

Customer service involves helping a customer gain the full use and advantage of whatever product or service was bought. When something goes wrong with a product, or when a customer has some kind of problem with it, the process of helping the customer overcome this problem is often referred to as customer care.

- Customer strategy

-

An organization’s plan for managing its customer experiences and relationships effectively in order to remain competitive. At its heart, customer strategy is increasing the value of the company by increasing the value of the customer base.

- Customer-strategy enterprise

-

An organization that builds its business model around increasing the value of the customer base. This term applies to companies that may be product oriented, operations focused, or customer intimate.

- Customer value management

-

Managing a business’s strategies and tactics (including sales, marketing, production, and distribution) in a manner designed to increase the value of its customer base.

- Interactive age

-

The current period in business and technological history, characterized by a dominance of interactive media rather than the one-way mass media more typical from 1910 to 1995. Also refers to a growing trend for businesses to encourage feedback from individual customers rather than relying solely on one-way messages directed at customers, and to participate with their customers in social networking. (Also called interactive era.)

- Interactive voice response (IVR)

-

Now a feature at most call centers, IVR software provides instructions for callers to “push ‘1’ to check your current balance, push ‘2’ to transfer funds,” and so forth.

- Lifetime value (LTV)

-

Synonymous with “actual value.” The net present value of the future financial contributions attributable to a customer, behaving as we expect her to behave—knowing what we know now, and with no different actions on our part.

- Market segment

-

A group of customers who share a common attribute. Product benefits are targeted to the market segments thought most likely to desire the benefit.

- Moment of truth (MoT)

-

Interactions with a customer that have a disproportionate impact on the customer’s emotional connection, and are therefore more likely to drive significant behaviors.

- Most valuable customers (MVCs)

-

Customers with high actual values but not a lot of unrealized growth potential. These are the customers who do the most business, yield the highest margins, are most willing to collaborate, and tend to be the most loyal.

- Needs

-

What a customer needs from an enterprise is, by our definition, synonymous with what she wants, prefers, or would like. In this sense, we do not distinguish a customer’s needs from her wants. For that matter, we do not distinguish needs from preferences, wishes, desires, or whims. Each of these terms might imply some nuance of need—perhaps the intensity of the need or the permanence of it—but in each case we are still talking, generically, about the customer’s needs.

- Potential value

-

The net present value of the future financial contributions that could be attributed to a customer, if through conscious action we succeed in changing the customer’s behavior.

- Relationship governance

-

Defines who in the enterprise will be in charge when making different decisions for different customers, with the goal of optimizing around each customer rather than each product or channel.

- Relationship manager

-

See customer manager.

- Return on Customer (ROC)

-

A metric directly analogous to return on investment (ROI), specifically designed to track how well an enterprise is using customers to create value. ROC equals a company’s current-period cash flow (from customers) plus the change in customer equity during the period, divided by the customer equity at the beginning of the period. ROC is pronounced are-oh-see.

- Supply chain

-

A company’s back-end production or service-delivery operations.

- Value of the customer base

-

See Customer equity.