Chapter 1

Evolution of Relationships with Customers and Strategic Customer Experiences

No company can succeed without customers. If you don’t have customers, you don’t have a business. You have a hobby.

—Don Peppers and Martha Rogers

The dynamics of the customer-enterprise relationship have changed dramatically over time. Customers have always been at the heart of an enterprise’s long-term growth strategies, marketing and sales efforts, product development, labor and resource allocation, and overall profitability directives. Historically, enterprises have encouraged the active participation of a sampling of customers in the research and development of their products and services. But until recently, enterprises have been structured and managed around the products and services they create and sell. Driven by assembly-line technology, mass media, and mass distribution, which appeared at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Industrial Age was dominated by businesses that sought to mass-produce products and to gain a competitive advantage by manufacturing a product that was perceived by most customers as better than its closest competitor. Product innovation, therefore, was the important key to business success. To increase its overall market share, the twentieth-century enterprise would use mass marketing and mass advertising to reach the greatest number of potential customers.

As a result, most twentieth-century products and services eventually became highly commoditized. Branding emerged to offset this perception of being like all the other competitors; in fact, branding from its beginning was, in a way, an expensive substitute for relationships companies could not have with their newly blossomed masses of customers. Facilitated by lots and lots of mass-media advertising, brands have helped add value through familiarity, image, and trust. Historically, brands have played a critical role in helping customers distinguish what they deem to be the best products and services. A primary enterprise goal has been to improve brand awareness of products and services and to increase brand preference and brand loyalty among consumers. For many consumers, a brand name has traditionally testified to the trustworthiness or quality of a product or service. Today, though, more and more, customers say they value brands, but their opinions are based on their “relationship with the brand”—so brand reputation is actually becoming one and the same with customers’ experience with the brand, product, or company (including relationships).1 Indeed, consumers are often content as long as they can buy one brand of a consumer-packaged good that they know and respect.

For many years, enterprises depended on gaining the competitive advantage from the best brands. Brands have been untouchable, immutable, and inflexible parts of the twentieth-century mass-marketing era. But in the interactive era of the twenty-first century, firms are instead strategizing how to gain sustainable competitive advantage from the information they gather about customers. As a result, enterprises are creating a two-way brand, one that thrives on customer information and interaction. The two-way brand, or branded relationship, transforms itself based on the ongoing dialogue between the enterprise and the customer. The branded relationship is “aware” of the customer (giving new meaning to the term brand awareness) and constantly changes to suit the needs of that particular individual. In current discussions, the focus is on ways to redefine the “brand reputation” as more customer oriented, using phrases such as “brand engagement with customer,” “brand relationship with customer,” and the customer’s “brand experience.” Add to this the transparency for brands and rampant ratings for products initiated by social media, and it’s clear why companies are realizing that what customers say about them is more important than what the companies say about themselves.

Roots of Customer Relationships and Experience

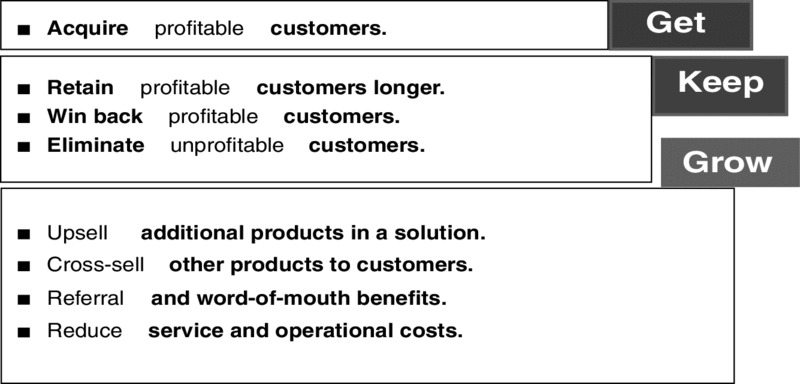

Once you strip away all the activities that keep everybody busy every day, the goal of every enterprise is simply to get, keep, and grow customers. This is true for nonprofits (where the “customers” may be donors or volunteers) as well as for-profits, for small businesses as well as large, for public as well as private enterprises. It is true for hospitals, governments, universities, and other institutions as well. What does it mean for an enterprise to focus on its customers as the key to competitive advantage? Obviously, it does not mean giving up whatever product edge or operational efficiencies might have provided an advantage in the past. It does mean using new strategies, nearly always requiring new technologies, to focus on growing the value of the company by deliberately and strategically growing the value of the customer base.

To some executives, customer relationship management (CRM) is a technology or software solution that helps track data and information about customers to enable better customer service. Others think of CRM, or one-to-one, as an elaborate marketing or customer service discipline. We even recently heard CRM described as “personalized e-mail.”

To us, “managing customer experience and relationships” is what companies do to optimize the value of each customer, and “managing customer experiences” is what companies do because they understand the customer’s perspective and what it is—and should be—like to be our customer. This book is about much more than setting up a business Web site or redirecting some of the mass-media budget into the call-center database or cloud analytics or social networking. It’s about increasing the value of the company through specific customer strategies (see Exhibit 1.1).

Exhibit 1.1 Increasing the Value of the Customer Base

Companies determined to build successful and profitable customer relationships understand that the process of becoming an enterprise focused on building its value by building customer value doesn’t begin with installing technology, but instead begins with:

- A strategy or an ongoing process that helps transform the enterprise from a focus on traditional selling or manufacturing to a customer focus while increasing revenues and profits in the current period and the long term.

- The leadership and commitment necessary to cascade throughout the organization the thinking and decision-making capability that puts customer value and relationships first as the direct path to increasing shareholder value.

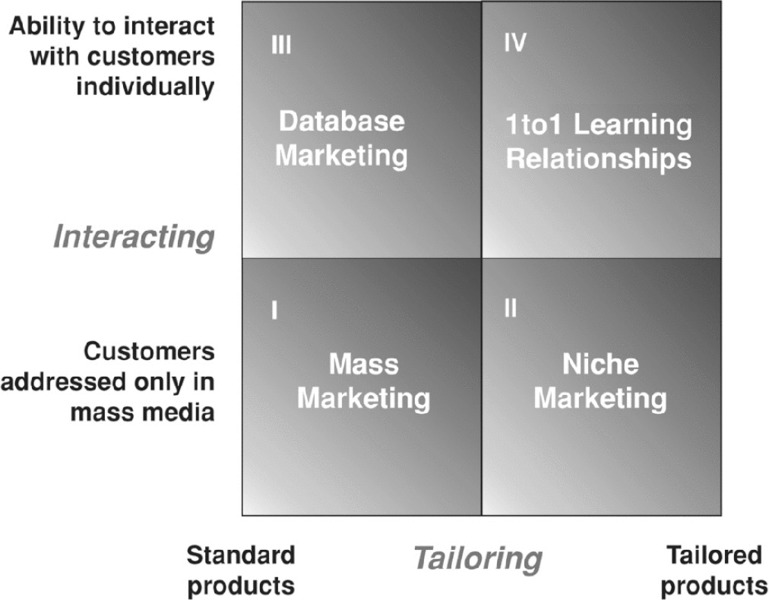

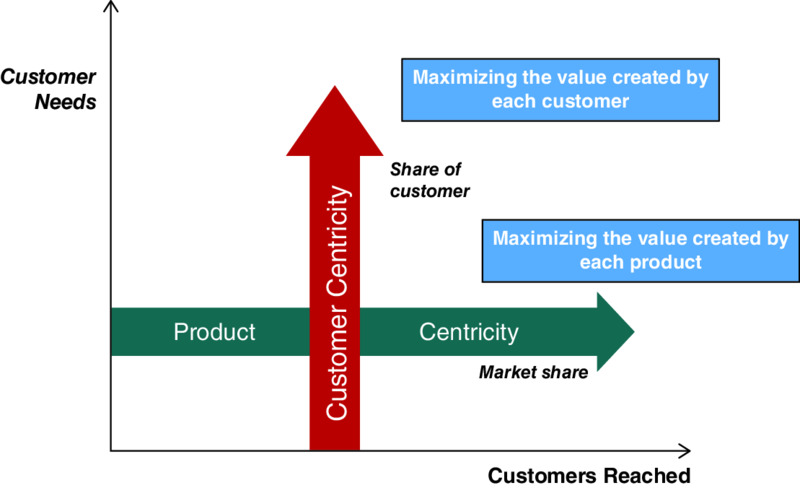

The reality is that becoming a customer-strategy enterprise is about using information to gain a competitive advantage and deliver growth and profit. In its most generalized form, CRM can be thought of as a set of business practices designed, simply, to put an enterprise into closer and closer touch with its customers, in order to learn more about each one and to deliver greater and greater value to each one, with the overall goal of making each one more valuable to the firm to increase the value of the enterprise. It is an enterprise-wide approach to understanding and influencing customer behavior through meaningful analysis and communications to improve customer acquisition, customer retention, and customer profitability.2 Customer centricity is distinguishable from product centricity and from technology centricity. These differences will be discussed more in Exhibit 1.3 later in this chapter.

Exhibit 1.2 Enterprise Strategy Map

Source: Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, Ph.D., Enterprise One to One (New York: Doubleday/Currency, 1997).

Exhibit 1.3 Objective of Customer Centricity

Defined more precisely, what makes customer centricity into a truly different model for doing business and competing in the marketplace, is this: It is an enterprise-wide business strategy for achieving customer-specific objectives by taking customer-specific actions. It is enterprise-wide because it can’t merely be assigned to marketing if it is to have any hope of success. Its objectives are customer-specific because the goal is to increase the value of each customer. Therefore, the firm will take customer-specific actions for each customer, often made possible by new technologies.

In essence, building the value of the customer base requires a business to treat different customers differently. Today, there is a customer-focus revolution under way among businesses. It represents an inevitable— literally, irresistible—movement. All businesses will be embracing customer strategies sooner or later, with varying degrees of enthusiasm and success, for two primary reasons:

- All customers, in all walks of life, in all industries, all over the world, want to be individually and personally served.

- It is simply a more efficient way of doing business.

We find examples of customer-specific behavior, and business initiatives driven by customer-specific insights, all around us today3:

- An airline offers a passenger in the airport waiting for his flight to arrive an upgrade offer to business class through a phone app he has used to check his flight status, as an apology for a 45-minute departure delay.

- A woman receives an e-mail before her eight-month obstetrics appointment that gives information about what to expect at the appointment and her baby’s stage of growth. A month later, the same woman receives a notification of her baby’s immunization appointment that is triggered when she leaves the hospital with her newborn.

- A retail clothes company sends a message to a customer it knows is standing outside one of their stores to come in and use a 15 percent discount, sometimes with a sweetener such as free shipping. Or the items appear as a reminder next to the newspaper articles the shopper reads next morning.

- A business sees that a customer has left their Web site, abandoning a cart with selected products before checkout, and sends an e-mail with more detailed information about those specific products to the customer the next day.

- An outdoor gear company sees that their tents are being discussed on a social channel and sends a free tent as a trial sample to a consistent product supporter.

- A group of three friends open the Web page of the same kitchenware company that they all have ordered from in the past. Each friend views a different offer featured on the company home page on her device.

- A customer service representative sees a complaint a customer has made on a social channel and is able to view at the same time his purchasing history and order status. The service rep uses that information to reply to the complaint via the same social channel.

- Instead of mailing out the same offer to everyone, a company waits for specific trigger behavior from a customer and increases response rates 25-fold.

- An insurance company not only handles a claim for property damage but also connects the insured party with a contractor in her area who can bypass the purchasing department and do the repairs directly.

- A supervisor orders more computer components by going to a Web page that displays his firm’s contract terms, his own spending to date, and his departmental authorizations.

- Sitting in the call center, a service rep sees a “smart dialogue” suggestion pop onto a monitor during a call with a customer, suggesting a question the company wants to ask that customer (not the same question being asked of all customers who call this week).

Taking customer-specific action, treating different customers differently, improving each customer’s experience with the company or product, building the value of the customer base, creating and managing relationships with individual customers that go on through time to get better and deeper—that’s what this book is about. In the chapters that follow, we will look at lots of examples. The overall business goal of this strategy is to make the enterprise as profitable as possible over time by taking steps to increase the value of the customer base. The enterprise makes itself, its products, and/or its services so satisfying, convenient, or valuable to the customer that she becomes more willing to devote her time and money to this enterprise than to any competitor. Building the value of customers increases the value of the demand chain, the stream of business that flows from the customer down through the retailer all the way to the manufacturer. A customer-strategy enterprise interacts directly with an individual customer. The customer tells the enterprise about how he would like to be served. Based on this interaction, the enterprise, in turn, modifies its behavior with respect to this particular customer. In essence, the concept implies a specific, one-customer-to-one-enterprise relationship, as is the case when the customer’s input drives the enterprise’s output for that particular customer.4

A suite of buzzwords have come to surround this endeavor: customer relationship management (CRM), one-to-one marketing, customer experience management, customer value management, customer focus, customer orientation, customer centricity, customer experience journey mapping, and more. You can see it in the titles on the business cards: Chief Marketing Officer, of course, but also a host of others, including “Chief Relationship Officer,” “Customer Care Leader,” “Customer Value Management Director,” and even “Customer Revolutionary” at one firm. Like all new initiatives, this customer approach (different from the strictly financial approach or product-profitability approach of the previous century) suffers when it is poorly understood, improperly applied, and incorrectly measured and managed. But by any name, strategies designed to build the value of the customer base by building relationships with one customer at a time, or with well-defined groups of identifiable customers, are by no means ephemeral trends or fads any more than computers or connectivity are.

A good example of a business offering that benefits from individual customer relationships can be seen in online banking services, in which a consumer spends several hours, usually spread over several sessions, setting up an online account and inputting payee addresses and account numbers, in order to be able to pay bills electronically each month. If a competitor opens a branch in town offering slightly lower checking fees or higher savings rates, this consumer is unlikely to switch banks. He has invested time and energy in a relationship with the first bank, and it is simply more convenient to remain loyal to the first bank than to teach the second bank how to serve him in the same way. In this example, it should also be noted that the bank now has increased the value of the customer to the bank and has simultaneously reduced the cost of serving the customer, as it costs the bank less to serve a customer online than at the teller window or by phone.

Clearly, “customer strategy” involves much more than marketing, and it cannot deliver optimum return on investment of money or customers without integrating individual customer information into every corporate function, from customer service to production, logistics, and channel management. A formal change in the organizational structure usually is necessary to become an enterprise focused on growing customer value. As this book shows, customer strategy is both an operational and an analytical process. Operational CRM focuses on the software installations and the changes in process affecting the day-to-day operations of a firm—operations that will produce and deliver different treatments to different customers. Analytical CRM focuses on the strategic planning needed to build customer value as well as the cultural, measurement, and organizational changes required to implement that strategy successfully.

Focusing on Customers Is New to Business Strategy

The move to a customer-strategy business model has come of age at a critical juncture in business history, when managers are deeply concerned about declining customer loyalty as a result of greater transparency and universal access to information, declining trust in many large institutions and most businesses, and increasing choices for customers. As customer loyalty decreases, profit margins decline, too, because the most frequently used customer acquisition tactic is price cutting. Enterprises are facing a radically different competitive landscape as the information about their customers is becoming more plentiful and as the customers themselves are demanding more interactions with companies and creating more connections with each other. Thus, a coordinated effort to get, keep, and grow valuable customers has taken on a greater and far more relevant role in forging a successful long-term, profitable business strategy.

If the last quarter of the twentieth century heralded the dawn of a new competitive arena, in which commoditized products and services have become less reliable as the source for business profitability and success, it is the new computer technologies and applications that have arisen that assist companies in managing their interactions with customers. These technologies have spawned enterprise-wide information systems that help to harness information about customers, analyze the information, and use the data to serve customers better. Technologies such as enterprise resource planning (ERP) systems, supply chain management (SCM) software, enterprise application integration (EAI) software, data warehousing, sales force automation (SFA), marketing resource management (MRM), and a host of other enterprise software applications have helped companies to mass-customize their products and services, literally delivering individually configured communications, products, or services to unique customers in response to their individual feedback and specifications.

The accessibility of the new technologies is motivating enterprises to reconsider how they develop and manage customer relationships and map the customer experience journey. More and more chief executive officers (CEOs) of leading enterprises have made the shift to a customer-strategy business model a top business priority for the twenty-first century. Technology is making it possible for enterprises to conduct business at an intimate, individual customer level. Indeed, technology is driving the shift. Computers can enable enterprises to remember individual customer needs and estimate the future potential revenue the customer will bring to the enterprise. What’s clear is that technology is the enabler; it’s the tail, and the one-to-one customer relationship is the dog.

Managing Customer Relationships and Experience Is a Different Dimension of Competition

The story goes that in 1996, the executives at Barnes & Noble bookstores invited Jeff Bezos, the founder of a startup named Amazon.com, to lunch, with a proposition. Amazon.com had not yet made any profit (and would not, for its first 28 quarters in a row), so the nice guys at the well-established bookstore offered, as a favor to Jeff, to buy him out—before they launched barnesandnoble.com, the online version of the bookstore chain. They argued that Jeff’s relatively unknown brand would not stand up to their highly popular name and that he should make some money on his software and systems. He declined.

How did that turn out? Twenty years after that lunch meeting, in 2016, Barnes & Noble had a market cap of US$667 million and Amazon.com had a market cap of US$323 billion.5 So whether the lunch ever really took place or not, the story still serves to illustrate the fundamental difference between a very well run product-oriented company (Barnes & Noble, which has stores to populate with products and tries to find customers for those products) and a fairly well run customer-oriented company (Amazon.com, which got us all as customers to buy books and DVDs, and now wants to sell each of us everything). Note: One of the authors, who lives in New York City, found the best selection and service from Amazon.com for a refrigerator bought for and installed in an Upper West Side apartment.

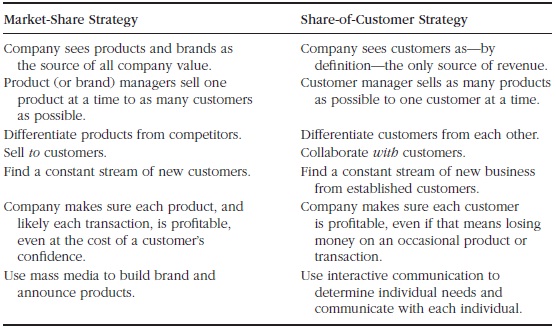

A lot can be understood about how traditional, market-driven competition is different from today’s customer-driven competition by examining Exhibit 1.3. The direction of success for a traditional aggregate-market enterprise (i.e., a traditional company that sees its customers in markets of aggregate groups) is to acquire more customers (widen the horizontal bar), whereas the direction of success for the customer-driven enterprise is to keep customers longer and grow them bigger (lengthen the vertical bar). The width of the horizontal bar can be thought of as an enterprise’s market share—the proportion of total customers who have their needs satisfied by a particular enterprise, or the percentage of total products in an industry sold by this particular firm. But the customer-value enterprise focuses on share of customer—the percentage of this customer’s business that a particular firm gets—represented by the height of the vertical bar. Think of it this way: Kellogg’s can either sell as many boxes of Corn Flakes as possible to whomever will buy them, even though sometimes Corn Flakes will cannibalize Raisin Bran sales, or Kellogg’s can concentrate on making sure its products are on Mrs. Smith’s breakfast table every day for the rest of her life, and thus represent a steady or growing percentage of that breakfast table’s offerings. Toyota can try to sell as many Camrys as possible, for any price, to anyone who will buy; or it can, by knowing Mrs. Smith better, make sure all the cars in Mrs. Smith’s garage are Toyota brands, including the used car she buys for her teenage son, and that Mrs. Smith uses Toyota financing, and gets her service, maintenance, and repairs at Toyota dealerships throughout her driving lifetime.

Although the tasks for growing market share are different from those for building share of customer, the two strategies are not antithetical. A company can simultaneously focus on getting new customers and growing the value of and keeping the customers it already has.6 Customer-strategy enterprises are required to interact with a customer and use that customer’s feedback from this interaction to deliver a customized product or service. Market-driven efforts can be strategically effective and even more efficient at meeting individual customer needs when a customer-specific philosophy is conducted on top of them. The customer-driven process is time-dependent and evolutionary, as the product or service is continuously fine-tuned and the customer is increasingly differentiated from other customers.

The principles of a customer-focused business model differ in many ways from mass marketing. Specifically:

The aggregate-market enterprise competes by differentiating products, whereas the customer-driven enterprise competes by differentiating customers.

The traditional, aggregate-market enterprise attempts to establish an actual product differentiation (by launching new products or modifying or extending established product lines) or a perceived one (with advertising and public relations). The customer-driven enterprise caters to one customer at a time and relies on differentiating each customer from all the others.

The traditional marketing company, no matter how friendly, ultimately sees customers as adversaries, and vice versa. The company and the customer play a zero-sum game: If the customer gets a discount, the company loses profit margin. Their interests have traditionally been at odds: The customer wants to buy as much product as possible for the lowest price, while the company wants to sell the least product possible for the highest price. If an enterprise and a customer have no relationship prior to a purchase, and they have no relationship following it, then their entire interaction is centered on a single, solitary transaction and the profitability of that transaction. Thus, in a transaction-based, product-centric business model, buyer and seller are adversaries, no matter how much the seller may try not to act the part. In this business model, practically the only assurance a customer has that he can trust the product and service being sold to him is the general reputation of the brand itself.7

By contrast, the customer-based enterprise aligns customer collaboration with profitability. Compare the behaviors that result from both sides if each transaction occurs in the context of a longer-term relationship. For starters, a one-to-one enterprise would likely be willing to fix a problem raised by a single transaction at a loss if the relationship with the customer were profitable long term (see Exhibit 1.4).

Exhibit 1.4 Comparison of Market-Share and Share-of-Customer Strategies

The central purpose of managing customer relationships and experiences is for the enterprise to focus on increasing the overall value of its customer base—and customer retention is critical to its success. Increasing the value of the customer base, whether through cross-selling (getting customers to buy other products and services), upselling (getting customers to buy more expensive offerings), or customer referrals, will lead to a more profitable enterprise. The enterprise can also reduce the cost of serving its best customers by making it more convenient for them to buy from the enterprise (e.g., by using Amazon’s one-click ordering process or online banking rather than a bank teller).

Technology Accelerates—It Is Not the Same as—Building Customer Value

The interactive era has accelerated the adoption and facilitation of this highly interactive collaboration between the customer and the company. In addition, technological advancements have contributed to an enterprise’s capability to capture the feedback of its customer, then customize some aspect of its products or services to suit each customer’s individual needs. Enterprises require a highly sophisticated level of integrated activity to enable this customization and personalized customer interaction to occur. To effectuate customer-focused business relationships, an enterprise must integrate the disparate information systems, databases, business units, customer touchpoints—everywhere the company touches the customer and vice versa—and many other facets of its business to ensure that all employees who interact with customers have real-time access to current customer information. The objective is to optimize each customer interaction and ensure that the dialogue is seamless—that each conversation picks up from where the last one ended. And to participate in a transparent and helpful way in conversations customers have with each other online.

Many software companies have developed enterprise point solutions and suites of software applications that, when deployed, elevate an enterprise’s capabilities to transform itself to a customer-driven model. And as we said earlier, while one-to-one customer relationships are enabled by technology, executives at firms with strong customer relationships and burgeoning customer equity (CE) believe that the enabling technology should be viewed as the means to an end, not the end itself. Managing customer experiences and relationships is an ongoing business process, not merely a technology. But technology has provided the catalyst for CRM to manifest itself within the enterprise. Computer databases help companies remember and keep track of individual interactions with their customers. Within seconds, customer service representatives can retrieve entire histories of customer transactions and make adjustments to customer records. Technology has made possible the mass customization of products and services, enabling businesses to treat different customers differently, in a cost-efficient way. (You’ll find more about mass customization in Chapter 10.) Technology empowers enterprises and their customer contact personnel, marketing and sales functions, and managers by equipping them with substantially more intelligence about their customers.

Implementing an effective customer strategy can be challenging and costly because of the sophisticated technology and skill set needed by relationship managers to execute the customer-driven business model. A business model focused on building customer value often requires the coordinated delivery of products and services aligned with enterprise financial objectives that meet customer value requirements. While enterprises are experimenting with a wide array of technology and software solutions from different vendors to satisfy their customer-driven needs, they are learning that they cannot depend on technology alone to do the job. Before it can be implemented successfully, managing customer relationships individually requires committed leadership from the upper management of the enterprise and wholehearted participation throughout the organization as well. Although customer strategies are driven by new technological capabilities, the technology alone does not make a company customer-centric. The payoff can be great, but the need to build the strategy to get, keep, and grow customers is even more important than the technology required to implement that strategy.

The foundation for an enterprise focused on building its value by building the value of the customer base is unique: Establish trustable relationships with customers on an individual basis, then use the information gathered to treat different customers differently and increase the value of each one to the firm. The overarching theme of such an enterprise is that the customer is the most valuable asset the company has; that’s why the primary goals are to get, keep, and grow profitable customers. Use technology to take the customer’s point of view, and act on that as a competitive advantage.

What Is a Relationship? Is That Different from Customer Experience?

What does it mean for an enterprise and a customer to have a relationship with each other? Do customers have relationships with enterprises that do not know them? Can the enterprise be said to have a relationship with a customer it does not know? Is a relationship possible if the company knows the customer and tailors offers and communications, remembers things for the customer, and deliberately builds customer experience—even if the customer is not aware of a “relationship”? Is it possible for a customer to have a relationship with a brand? Perhaps what is thought to be a customer’s relationship with a brand is more accurately described as the customer’s attitude or predisposition toward the brand. This attitude is a combination of impressions from actual experiences with that brand, as well as what one has heard about the brand from ads (company-originated communication), from news, and from others (comments from friends and ratings by strangers). Experts have studied the nature of relationships in business for many years, and there are many different perspectives on the fundamental purpose of relationships in business strategies.

This book is about managing customer relationships and experiences more effectively in the twenty-first century, which is governed by a more individualized approach. The critical business objective can no longer be limited to acquiring the most customers and gaining the greatest market share for a product or service. Instead, to be successful going forward, now that it’s possible to deal individually with separate customers, the business objective must include establishing meaningful and profitable relationships with, at the least, the most valuable customers and making the overall customer base more valuable. Technological advances during the last quarter of the twentieth century have mandated this shift in philosophy.

In short, the enterprise strives to get a customer, keep that customer for a lifetime, and grow the value of the customer to the enterprise. Relationships are the crux of the customer-strategy enterprise. Relationships between customers and enterprises provide the framework for everything else connected to the customer-value business model, even if the customer is not aware of the “relationship.” After all, the customer is aware of what she experiences with the company. In fact, we could say that managing the customer relationship is all about what the company does, and customer experience is what the customer feels like as a result. The exchange between a customer and the enterprise becomes mutually beneficial, as customers give information in return for personalized service that meets their individual needs. This interaction forms the basis of the Learning Relationship, based on a collaborative dialogue between the enterprise and the customer that grows smarter and smarter with each successive interaction.8

The basic strategy behind Learning Relationships is that the enterprise gives a customer the opportunity to teach it what he wants, remember it, give it back to him, and keep his business. The more the customer teaches the company, the better the company can provide exactly what the customer wants and the more the customer has invested in the relationship. Ergo, the customer will more likely choose to continue dealing with the enterprise rather than spend the extra time and effort required to establish a similar relationship elsewhere.9 The Learning Relationship works like this: If you’re my customer and I get you to talk to me, and I remember what you tell me, then I get smarter and smarter about you. I know something about you that my competitors don’t know. So I can do things for you my competitors can’t do, because they don’t know you as well as I do. Before long, you can get something from me you can’t get anywhere else, for any price. At the very least, you’d have to start all over somewhere else, but starting over is more costly than staying with me, so long as you like me and trust me to look out for your best interests. This happens every time a customer buys groceries by updating her online grocery list10 or adds a favorite movie to her “My List” online. Even if a competitor were to establish exactly the same capabilities, a customer already involved in a Learning Relationship with an enterprise would have to spend time and energy—sometimes a lot of time and energy—teaching the competitor what the current enterprise already knows. This creates a significant switching cost for the customer, as the value of what the enterprise is providing continues to increase, partly as the result of the customer’s own time and effort. The result is that the customer becomes more loyal to the enterprise because it is simply in the customer’s own interest to do so. It is more worthwhile for the customer to remain loyal than to switch. As the relationship progresses, the customer’s convenience increases, and the enterprise becomes more valuable to the customer, allowing the enterprise to protect its profit margin with the customer, often while reducing the cost of serving that customer. Learning Relationships provide the basis for a completely different arena of competition, separate and distinct from traditional, product-based competition. An enterprise cannot prevent its competitor from offering a product or service that is perceived to be as good as its own offering. Once a competitor offers a similar product or service, the enterprise’s own offering is reduced to commodity status. But enterprises that engage in collaborative Learning Relationships with individual customers gain a distinct competitive advantage because they know something about one customer that a competitor does not know. In a Learning Relationship, the enterprise learns about an individual customer through his transactions and interactions during the process of doing business. The customer, in turn, learns about the enterprise through his successive purchase experiences and other interactions. Thus, in addition to an increase in customer loyalty, two other benefits come from Learning Relationships: Cultivating Learning Relationships depends on an enterprise’s capability to elicit and manage useful information about customers. Customers, whether they are consumers or other enterprises, do not want more choices. Customers simply want exactly what they want—when, where, and how they want it. And technology is now making it more and more possible for companies to give it to them, allowing enterprises to collect large amounts of data on individual customers’ needs and then use that data to customize products and services for each customer—that is, to treat different customers differently.12 This ability to use customer information to offer a customer the most relevant product at the right price, at the right moment, is at the heart of the kind of customer experience that builds share of customer and loyalty. One of the implications of this shift is an imperative to consider and manage the two ways customers create value for an enterprise. We’ve already said that a product focus tends to make companies think more about the value of a current transaction than the long-term value of the customer who is the company’s partner in that transaction. But building Learning Relationships has value only to a company that links its own growth and future success to its ability to keep and grow customers, and therefore commits to building long-term relationships with customers. This means we find stronger commitments to customer trust, employee trust, meeting community responsibilities, and otherwise thinking about long-term, sustainable strategies. Companies that are in the business of building the value of the customer base are companies that understand the importance of balancing short-term and long-term success. We talk more about that in Chapters 5 and 11. When it comes to customers, businesses are shifting their focus from product sales transactions to relationship equity. Most soon recognize that they simply do not know the full extent of their profitability by customer.13 Not all customers are equal. Some are not worth the time or financial investment of establishing Learning Relationships, nor are all customers willing to devote the effort required to sustain such a relationship. Enterprises need to decide early on which customers they want to have relationships with, which they do not, and what type of relationships to nurture. (See Chapter 5 on customer value differentiation.) But the advantages to the enterprise of growing Learning Relationships with valuable and potentially valuable customers are immense. Because much of what is sold to the customer may be customized to his precise needs, the enterprise can, for example, potentially charge a premium (as the customer may be less price sensitive to customized products and services) and increase its profit margin.14 The product or service is worth more to the customer because he has helped shape and mold it to his own specifications. The product or service, in essence, has become decommoditized and is now uniquely valuable to this particular customer. Managing customer relationships effectively is a practice not limited to products and services. When establishing interactive Learning Relationships with valuable customers, customer-strategy enterprises remember a customer’s specific needs for the basic product but also the goods, services, and communications that surround the product, such as how the customer would prefer to be invoiced or how the product should be packaged. Even an enterprise that sells a commodity-like product or service can think of it as a bundle of ancillary services, delivery times, invoicing schedules, personalized reminders and updates, and other features that are rarely commodities. The key is for the enterprise to focus on customizing to each individual customer’s needs. A teenager in California had gotten a text from her wireless phone service suggesting her parents could save money if she texted “4040” in an offer to switch her to a cell phone plan that was a better fit for her and the way she actually uses the service. She was so impressed she made a point of telling us about it. And of course, she told all her friends at school—and on Twitter and Facebook. The coverage, the hardware, the central customer service, and the “brand” all remained the same. But the customer experience, based on actual usage interaction with the customer—information not available to competitors—improved the customer relationship, increased loyalty and lifetime value of the customer, and positively influenced other customers as well. When a customer teaches an enterprise what he wants or how he wants it, the customer and the enterprise are, in essence, collaborating on the sale of the product. The more the customer teaches the enterprise, the less likely the customer will want to leave. The key is to design products, services, and communications that customers value, and on which a customer and a marketer will have to collaborate for the customer to receive the product, service, or benefit. Enterprises that build Learning Relationships clear a wider path to customer profitability than companies that focus on price-driven transactions. They move from a make-to-forecast business model to a make-to-order model, as Dell Computer did when it created a company that reduced inventory levels by building each computer after it was paid for. By focusing on gathering information about individual customers and using that information to customize communications, products, and services, enterprises can more accurately predict inventory and production levels. Fewer orders may be lost because mass customization can build the products on demand and thus make available to a given customer products that cannot be stocked ad infinitum. (Again, we will discuss customization further in Chapter 10.) Inventoryless distribution from a made-to-order business model can prevent shortages caused in distribution channels as well as reduce inventory carrying costs. The result is fewer “opportunity” losses. Furthermore, efficient mass-customization operations can ship built-to-order custom products faster than competitors that have to customize products from scratch.15 Learning Relationships have less to do with creating a fondness on the part of a customer for a particular product or brand and more to do with a company’s capability to remember and deliver based on prior interactions with a customer. An enterprise that engages in a Learning Relationship creates a bond of value for the customer, a reason for an individual customer or small groups of customers with similar needs to lose interest in dealing with a competitor, provided that the enterprise continues to deliver a product and service quality at a fair price and to remember to act on the customer’s preferences and tastes.16 Learning Relationships may also be based on an inherent trust between a customer and an enterprise. For example, a customer might divulge his credit card number to an organization, which records it and remembers it for future transactions. The customer trusts that the enterprise will keep his credit card number confidential. The enterprise makes it easier and faster for him to buy because he no longer has to repeat his credit card number each time he makes a purchase. (In the next chapter, we’ll learn more about the link between attitude and behavior in relationships.)Learning Relationships: The Crux of Managing Customer Relationships

The Technology Revolution and the Customer Revolution

During the past century, as enterprises sought to acquire as many customers as they possibly could, the local proprietor’s influence over customer purchases decreased. Store owners or managers became little more than order takers, stocking their shelves with the goods that consumers would see advertised in the local newspaper or on television and radio. Mass-media advertising became a more effective way to publicize a product and generate transactions for a wide audience. But now technology has made it possible, and therefore competitively necessary, for enterprises to behave, once again, like small-town proprietors and deal with their customers individually, one customer at a time.

At the same time, technology has generated a business model that we will refer to as the trust platform.17 Becoming prominent since the last edition of this book, trust platforms are epitomized by companies such as Uber, Airbnb, and TaskRabbit. This kind of business depends on using interactive technology to connect willing buyers with willing sellers, while relying on crowd-sourced feedback to ensure mutual trust. Rather than a “sharing” economy, trust platforms facilitate an “initiative” economy, based on the entrepreneurial initiatives of thousands of individuals, all seamlessly connected to the larger network.

We must note that social interactions are not as manageable as a company’s marketing and other functions are. The social interactions a company has with customers and other people can’t be directed the same way advertising campaigns or cost-cutting initiatives can. Instead, in the e–social world, what companies are likely to find is that top-down, command-and-control organizations are not trustable, while self-organized collections of employees and partners motivated by a common purpose and socially empowered to take action are more trustable.

Customers Have Changed, Too

The technological revolution has spawned another revolution, one led by the customers themselves, who now demand products just the way they want them and flawless customer service. Enterprises are realizing that they really know little or nothing about their individual customers and so are mobilizing to capture a clearer understanding of each customer’s needs. Customers, meanwhile, want to be treated less like numbers and more like the individuals they are, with distinct, individual requirements and preferences. They are actively communicating these demands back to the enterprise (and, through social media and mobile apps, with each other!). Where they would once bargain with a business, they now tell managers of brand retail chains what they are prepared to pay and specify how they want products designed, styled, assembled, delivered, and maintained. When it comes to ordering, consumers want to be treated with respect. The capability of an enterprise to remember customers and their logistical information not only makes ordering easier for customers but also lets them know that they are important. Computer applications that enable options such as “one-click,” or express, ordering on the Web are creating the expectation that good online providers take the time to get to know customers as individuals so they can provide this higher level of service.18

The customer revolution is part of the reason enterprises are committing themselves to keep and grow their most valuable customers. Today’s consumers and businesses have become more sophisticated about shopping for their needs across multiple channels; more and more CMOs refer to this multiple channel marketing as omnichannel marketing, but what it really means is that customers will come at companies in various ways, in ways that suit those customers, and companies must be ready to present a logical, coherent response to each customer—not just messages sent through media channels—and to remember what is learned through each interaction and apply that learning to all channels. The idea here is not just to make sure that we prepare and send a message, but to make sure each customer receives one. The online channel, in particular, enables shoppers to locate the goods and services they desire quickly and at a price they are willing to pay, which forces enterprises to compete on value propositions other than lowest price.

Customer Retention and Enterprise Profitability

Enterprises strive to increase profitability without losing high-margin customers by increasing their customer retention rates or the percentage of customers who have met a specified number of repurchases over a finite period of time. A retained customer, however, is not necessarily a loyal customer. The customer may give business to a competing enterprise for many different reasons.

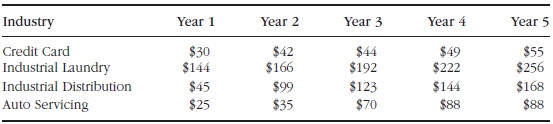

In 1990, Fred Reichheld and W. Earl Sasser analyzed the profit per customer in different service areas, categorized by the number of years that a customer had been with a particular enterprise.19 In this groundbreaking study, they discovered that the longer a customer remains with an enterprise, the more profitable she becomes. Average profit from a first-year customer for the credit card industry was $30; for the industrial laundry industry, $144; for the industrial distribution industry, $45; and for the automobile servicing industry, $25.

Four factors contributed to the underlying profit growth:

- Profit derived from increased purchases. Customers grow larger over time and need to purchase in greater quantities.

- Profit from reduced operating costs. As customers become more experienced, they make fewer demands on the supplier and fewer mistakes when involved in the operational processes, thus contributing to greater productivity for the seller and for themselves.

- Profit from referrals to other customers. Less needs to be spent on advertising and promotion due to word-of-mouth recommendations from satisfied customers.

- Profit from price premium. New customers can benefit from introductory promotional discounts, while long-term customers are more likely to pay regular prices.

No matter what the industry, the longer an enterprise keeps a customer, the more value that customer can generate for shareholders.20 Reichheld and Sasser found in a classic study that for one auto service company, the expected profit from a fourth-year customer is more than triple the profit that same customer generates in the first year. Other industries studied showed similar positive results (see Exhibit 1.5).

Exhibit 1.5 Profit One Customer Generates over Time

Source: Frederick F. Reichheld and W. Earl Sasser Jr., “Zero Defections: Quality Comes to Services,” Harvard Business Review 68:5 (September–October 1990): 106.

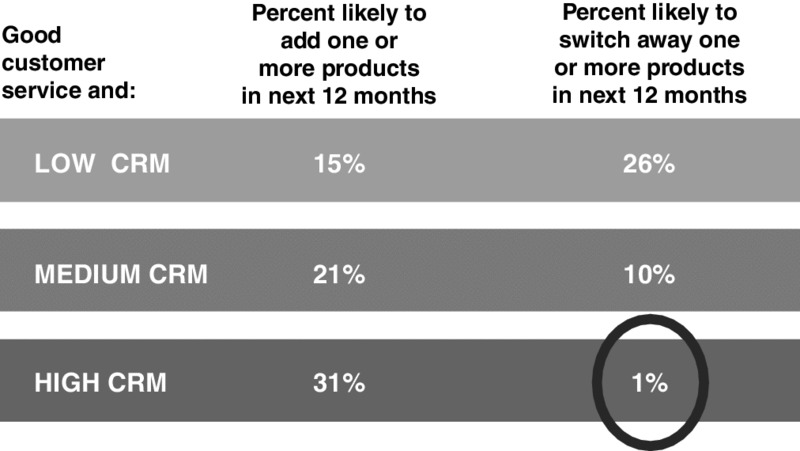

Enterprises that build stronger individual customer relationships enhance customer loyalty, as they are providing each customer with what he needs.21 Loyalty building requires the enterprise to emphasize the value of its products or services and to show that it is interested in building a relationship with the customer.22 The enterprise realizes that it must build a stable customer base rather than concentrate on single sales.23

A customer-strategy firm will want to reduce customer defections because they result in the loss of investments the firm has made in creating and developing customer relationships. Customers are the lifeblood of any business. They are, literally, the only source of its revenue24 Loyal customers are more profitable because they likely buy more over time if they are satisfied. It costs less for the enterprise to serve retained customers over time because transactions with repeat customers become more routine. Loyal customers tend to refer other new customers to the enterprise, thereby creating new sources of revenue.25 It stands to reason that if the central goal of a customer-strategy company is to increase the overall value of its customer base, then continuing its relationships with its most profitable customers will be high on its list of priorities.

On average, U.S. corporations tend to lose half their customers in five years, half their employees in four, and half their investors in less than one.26 In his classic study on the subject, Fred Reichheld described a possible future in which the only business relationships will be onetime, opportunistic transactions between virtual strangers.27 However, he found that disloyalty could stunt corporate performance by 25 to 50 percent, sometimes more. In contrast, enterprises that concentrate on finding and keeping good customers, productive employees, and supportive investors continue to generate superior results. For this reason, the primary responsibility for customer retention or defection lies in the chief executive’s office.

Exhibit 1.6 Benefits of CRM in Financial Services

Source: Peppers & Rogers Group, Roper Starch Worldwide survey, September 2000.

Customer loyalty is closely associated with customer relationships and may, in certain cases, be directly related to the level of each customer’s satisfaction over time.28 According to James Barnes, satisfaction is tied to what the customer gets from dealing with a company as compared with what he has to commit to those dealings or interactions.29 For now, it’s enough to know that the customer satisfaction issue is controversial—maybe even problematic. There are issues of relativity (are laptop users just harder to satisfy than desktop users, or are they really less satisfied?) and skew (is the satisfaction score the result of a bunch of people who are more or less satisfied, or a bimodal group whose members either love or hate the product?). Barnes believes that by increasing the value that the customer perceives in each interaction with the company, enterprises are more likely to increase customer satisfaction levels, leading to higher customer retention rates. When customers are retained because they enjoy the service they are receiving, they are more likely to become loyal customers. This loyalty leads to repeat buying and increased share of customer. (We will discuss more about the differences between attitudinal loyalty and behavioral loyalty, as well as ways to measure loyalty and retention, in the next chapter.)

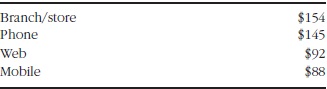

Retaining customers is more beneficial to the enterprise for another reason: Acquiring new customers is costly. Consider the banking industry. Averaging across channels, banks can spend at least $200 to replace each customer who defects. So if a bank has a clientele of 50,000 customers and loses 5 percent of those customers each year, it would need to spend $500,000 or more each year simply to maintain its customer base.30 Many Internet startup companies, without any brand-name recognition, faced an early demise during the 2000–2001 dot-com bubble bust, largely because they could not recoup the costs associated with acquiring new customers. The typical Internet “pure-play” spent an average of $82 to acquire one customer in 1999, a 95 percent increase over the $42 spent on average in 1998.31 Much of that increase can be attributed to the dot-com companies’ struggle to build brand awareness during 1999, which caused Web-based firms to increase offline advertising spending by an astounding 518 percent. Based on marketing costs related to their online business, in 1999, offline-based companies spent an average of $12 to acquire a new customer, down from $22 the previous year. Online firms spent an unsustainable 119 percent of their revenues on marketing in 1999. Even with the advantages of established brands, offline companies spent a still-high 36 percent.

The problem is simple arithmetic. Given the high cost of customer acquisition, a company can never realize any potential profit from most customers, especially if a customer leaves the franchise (see Exhibit 1.7). High levels of customer churn trouble all types of enterprises, not just those in the online and wireless industries. The problem partly results from the way companies reward sales representatives: with scalable commissions and bonuses for acquiring the most customers. Fact is, many reps have little, if any, incentive for keeping and growing an established customer. In some cases, if a customer leaves, the sales representative can even be rewarded for bringing the same customer back again!

Exhibit 1.7 Customer Acquisition Costs (2015)

Source: Martin Gill with Zia Daniell Wigder, Rachel Roizen, and Alexander Causey, “Use Customer-Centric Metrics to Benchmark Your Digital Success,” Forrester Research, Inc., February 5, 2015.

Although it’s always somebody’s designated mission to get new customers, too many companies still don’t have anybody responsible for making sure this or that particular customer sticks around or becomes profitable. Often, a service company with high levels of churn needs to rethink not only how its reps engage in customer relationships but also how they are rewarded (or not) for nurturing those relationships and for increasing the long-term value to the enterprise of particular customers. Throughout this book, we will see that becoming a customer-value enterprise is difficult. It is a strategy that can never be handled by one particular department within the enterprise. Managing customer relationships and experiences is an ongoing process—one that requires the support and involvement of every functional area in the organization, from the upper echelons of management through production and finance, to each sales representative or contact-center operator. Indeed, customer-driven competition requires enterprises to integrate five principal business functions into their overall customer strategy:

- Financial custodianship of the customer base. The customer-strategy enterprise treats the customer base as its primary asset and carefully manages the investment it makes in this asset, moving toward balancing the value of this asset to the long-term as well as the short-term success of the company.

- Production, logistics, and service delivery. Enterprises must be capable of customizing their offerings to the needs and preferences of each individual customer. The Learning Relationship with a customer is useful only to the extent that interaction from the customer is actually incorporated in the way the enterprise behaves toward that customer.

- Marketing communications, customer service, and interaction. Marketing communications and all forms of customer interaction and connectivity need to be combined into a unified function to ensure seamless individual customer dialogue.

- Sales distribution and channel management. A difficult challenge is to transform a distribution system that was created to disseminate standardized products at uniform prices into one that delivers customized products at individualized prices. Disintermediation of the distribution network by leaping over the “middleman” is sometimes one solution to selling to individual customers.

- Organizational management strategy. Enterprises must organize themselves internally by placing managers in charge of customers and customer relationships rather than of just products and programs.32

A customer-strategy enterprise seeks to create one centralized view of each customer across all business units. Every employee who interacts with a customer has to have real-time access to current information about that individual customer so that it is possible to pick up each conversation from where the last one left off. The goal is instant interactivity with the customer. This process can be achieved only through the complete and seamless integration of every enterprise business unit and process.

Summary

A customer-strategy enterprise seeks to identify what creates value for each customer and then to deliver that value to him. As other chapters in this book will demonstrate, a customer-value business strategy is a highly measurable process that can increase enterprise profitability and shareholder value. We also show that the foundation for growing a profitable customer-strategy enterprise lies in establishing stronger relationships with individual customers. Enterprises that foster relationships with individual customers pave a path to profitability. The challenge is to understand how to establish these critical relationships and how to optimize them for profits. Learning Relationships provide the framework for understanding how to build customer value.

Increasing the value of the customer base by focusing on customers individually and treating different customers differently will benefit the enterprise in many ways. But before we can delve into the intricacies of the business strategies behind this objective, and before we can review the CRM analytical tools and techniques required to carry out this strategy, we need to establish a foundation of knowledge with respect to how enterprises have developed relationships with customers over the years. That is our goal for the next chapter.

Food for Thought

- Understanding customers is not a new idea. Mass marketers have done it for years. But because they see everyone in a market as being alike—or at least everyone in a niche or a segment as being alike—they “understand” Customer A by asking 1,200 (or so) total strangers in a sample group from A’s segment a few questions, then extrapolating the average results to the rest of the segment, including A. This is logical if all customers in a group are viewed as homogeneous. What will a company likely do differently in terms of understanding customers if it is able to see one customer at a time, remember what each customer tells the company, and treat different customers differently?

- If retention is so much more profitable than acquisition, why have companies persisted for so long in spending more on getting new customers than keeping the ones they have? What would persuade them to change course?

- How can we account for the upheaval in orientation from focusing on product profitability to focusing on customer profitability? If it’s such a good idea, why didn’t companies operate from the perspective of building customer value 50 years ago?

- In the age of information (and connectivity), what will be happening to the four Ps, traditional advertising, and branding? What happens next?

- “The new interactive technologies are not enough to cement a relationship, because companies need to change their behavior toward a customer and not just their communication.” Explain what this statement means. Do you agree or disagree?

Glossary

- Analytical CRM (see also Operational CRM)

- The software installations, data requirements, and day-to-day procedural changes required at a firm to understand and anticipate individual customer needs, in order to be able to manage relationships better. In the four-step IDIC process, analytical CRM involves the first two steps, identifying and differentiating customers.

- Business model

- How a company builds economic value.

- Commoditization

- The steady erosion in unique selling propositions and unduplicated product features that comes about inevitably, as competitors seek to improve their offerings and end up imitating the more successful features and benefits.

- Customer care

- See Customer service.

- Customer centricity

- A “specific approach to doing business that focuses on the customer. Customer/client centric businesses ensure that the customer is at the center of a business philosophy, operations or ideas. These businesses believe that their customers/clients are the only reason they exist and use every means at their disposal to keep the customer/client happy and satisfied.”33 At the core of customer centricity is the understanding that customer profitability is at least as important as product profitability.

- Customer equity (CE)

- The value to the firm of building a relationship with a customer, or the sum of the value of all current and future relationships with current and potential customers. This term can be applied to individual customers or groups of customers, or the entire customer base of a company. See also the definition of customer equity in Chapter 11.

- Customer experience

- The totality of a customer’s individual interactions with a brand, over time.

- Customer experience journey mapping

- See Customer journey mapping.

- Customer experience management

- The processes, tools, and procedures required to affect individual customer experiences at an enterprise.

- Customer focus

- See Customer orientation.

- Customer journey mapping

- A process of diagramming all the steps a customer takes when engaging with a company to buy, use, or service its product or offering. Also called “customer experience journey mapping.” See the section on this subject in Chapter 13.

- Customer orientation

- An attitude or mind-set that attempts to take the customer’s perspective when making business decisions or implementing policies. Also called customer focus.

- Customer relationship management (CRM)

- As a term, CRM can refer either to the activities and processes a company must engage in to manage individual relationships with its customers (as explored extensively in this textbook), or to the suite of software, data, and analytics tools required to carry out those activities and processes more cost efficiently.

- Customer service

- Customer service involves helping a customer gain the full use and advantage of whatever product or service was bought. When something goes wrong with a product, or when a customer has some kind of problem with it, the process of helping the customer overcome this problem is often referred to as “customer care.”

- Customer strategy

- An organization’s plan for managing its customer experiences and relationships effectively in order to remain competitive. At its heart, customer strategy is increasing the value of the company by increasing the value of the customer base.

- Customer-strategy enterprise

- An organization that builds its business model around increasing the value of the customer base. This term applies to companies that may be product oriented, operations focused, or customer intimate.

- Customer value management

- Managing a business’s strategies and tactics (including sales, marketing, production, and distribution) in a manner designed to increase the value of its customer base.

- Data warehousing

- A process that captures, stores, and analyzes a single view of enterprise data to gain business insight for improved decision making.

- Demand chain

- As contrasted with the supply chain, “demand chain” refers to the chain of demand from customers, through retailers, distributors, and other intermediaries, all the way back to the manufacturer.

- Disintermediation

- Going directly to customers by skipping a usual distribution channel; for example, a manufacturer selling directly to consumers without a retailer.

- Enterprise resource planning (ERP)

- The automation of a company’s back-office management.

- Interactive era

- The current period in business and technological history, characterized by a dominance of interactive media rather than the one-way mass media more typical from 1910 to 1995. Also refers to a growing trend for businesses to encourage feedback from individual customers rather than relying solely on one-way messages directed at customers, and to participate with their customers in social networking.

- Multiple channel marketing

- An organization’s capability of selling through more than one distribution channel (e.g., a Web site, a toll-free number, mail-order catalog). Can also refer to the approach of interacting with customers through more than one channel of communication (e.g., a Web site form, online chat, social media, text, e-mail, fax, direct mail, phone).

- Omnichannel marketing

- A marketing buzzword referring to the capability of interacting and transacting with customers in any or all channels, in order to ensure that every interaction takes place in the channel of the customer’s own choice.

- One-to-one marketing

- The process of treating different customers differently and building ongoing relationships with individual customers, by using customer databases, interactivity, and mass-customization technologies. “One to one marketing” was originally espoused in the 1993 book The One to One Future: Building Relationships One Customer at a Time, by Don Peppers and Martha Rogers, Ph.D. As more technologies were developed to execute this kind of business strategy, the term customer relationship management came to be more frequently used.

- Operational CRM (see also Analytical CRM)

- The software installations, data requirements, and day-to-day procedural changes required at a firm to manage interactions and transactions with individual customers on an ongoing basis. In the four-step IDIC process, operational CRM involves the last two steps, interacting with and customizing for customers.

- Relationship equity

- See Customer equity.

- Sales force automation (SFA)

- Connecting the sales force to headquarters and to each other through computer portability, contact management, ordering software, and other mechanisms.

- Share of customer (SOC)

- For a customer-focused enterprise, share of customer is a conceptual metric designed to show what proportion of a customer’s overall need is being met by the enterprise. It is not the same as “share of wallet,” which refers to the specific share of a customer’s spending in a particular product or service category. If, for instance, a family owns two cars, and one of them is your car company’s brand, then you have a 50 percent share of wallet with this customer, in the car category. But by offering maintenance and repairs, insurance, financing, and perhaps even driver training or trip planning, you can substantially increase your “share of customer.”

- Social networking

- The ability of individuals to connect instantly with each other often and easily online in groups. For business, it’s about using technology to initiate and develop relationships into connected groups (networks), usually forming around a specific goal or interest.

- Switching cost

- The cost, in time, effort, emotion, or money, to a business customer or end-user consumer of switching to a firm’s competitor.

- Trust platform

- A business that uses interactive technology to connect willing buyers with willing sellers, while relying on crowd-sourced feedback to ensure mutual trust. Uber and Airbnb are examples of trust platforms.

- Value of the customer base

- See Customer equity.