Chapter 7

Interacting with Customers: Customer Collaboration Strategy

Most conversations are simply monologues delivered in the presence of witnesses.

—Margaret Millar

Managing customer experiences and individual customer relationships is a difficult, ongoing process that evolves as the customer and the enterprise deepen their awareness of and involvement with each other. To reach this new plateau of intimacy, the enterprise must get as close to the customer as it can. It must be able to understand the customer in ways that no competitor does. The only viable method of getting to know an individual, to understand him, and to get information about him is to interact with him—one to one.

In Chapter 2, we began to define customer experience and a relationship. We listed several important characteristics in our definition of the term relationship; but one of the most fundamental of these characteristics is interaction. A relationship, by its very definition, is characterized by two-way communication between the two parties to the relationship (and often, in an increasingly interconnected age, among all parties).

Interacting with customers acquires a new importance for a customer-strategy enterprise—an enterprise aimed at creating and cultivating relationships with individual customers. The enterprise is no longer merely talking to a customer during a transaction and then waiting (or hoping) the customer will return again to buy. For the customer-strategy enterprise, interacting with individual customers becomes a mutually beneficial experience. The enterprise learns about the customer so it can understand his value to the enterprise and his individual needs. But in a relationship the customer learns, too—about becoming a more proficient consumer or purchasing agent for a business. The interaction, in essence, is now a collaboration in which the enterprise and the customer work together to make this transaction, and each successive one, more beneficial for both. The focus shifts from a one-way message or a onetime sale to a continuous, iterative process, which de facto moves both customer and enterprise from a transactional approach to a relationship approach. The goal of the process is to be more and more satisfying for the customer, as the enterprise’s Learning Relationship with that customer improves. The result of this collaboration, if it is to be successful, is that both the customer and the enterprise will benefit and want to continue to work together. This is no longer about generating messages about your organization. This is about generating feedback, creating a collaborative feedback loop with each customer by treating her in a way that the customer herself has specified during the interaction, whether it’s face to face, via text, online, through social media, or all of the above.

Interacting with an individual customer enables an enterprise to become both an expert on its business and an expert on each of its customers. It comes to know more and more about a customer so that eventually it can predict what the customer will need next and where and how he will want it. Like a good servant of a previous century, the enterprise becomes indispensable.

Customer-strategy enterprises ensure that each customer gets exactly what he needs, no matter what, and this priority should extend from the front line all the way to upper management. Years ago, Southwest Airlines created a high-level position to coordinate all proactive customer communications—from the information sent to frontline representatives when flights are delayed, to personally sending letters and vouchers to customers thus inconvenienced. All the while, when the inevitable delay does occur, Southwest flight attendants and even pilots walk the aisles to update passengers and answer questions, conveying genuine concern in the moment. For a company to be truly customer-centric, interaction must happen at all levels, so as many employees as possible know what it feels like to be a customer.1

More and more, this learning and feedback includes participation in the social media where your customers hang out—new media that are developing so fast that a listing here would be outdated by the time this book hits print.

In this chapter, we show how a customer-strategy enterprise interacts with its customers in order to generate and use individual feedback from each customer to strengthen and deepen its relationship with that customer. This two-way communication can best be referred to as a dialogue, which serves to inform the relationship.

Dialogue Requirements

An enterprise should meet six criteria before it can be considered engaged in a genuine dialogue with an individual customer:

- Parties at both ends have been clearly identified. The enterprise knows who the customer is, if he has shopped there before, what he has bought, and other characteristics about him. The customer, too, knows which enterprise he’s doing business with.

- All parties in the dialogue must be able to participate in it. Each party should have the means to communicate with the other. Until the arrival of cost-efficient interactive technologies, and especially the Internet, social media, and mobile, most marketing-oriented interactions with individual customers were prohibitively costly, and it was very difficult for a customer to make herself heard.

- All parties to a dialogue must want to participate in it. The subject of a dialogue must be of interest to the customer as well as to the enterprise.

- Dialogues can be controlled by anyone in the exchange. A dialogue involves mutuality, and as a mutual exchange of information and points of view, it might go in any direction that either party chooses for it. This is in contrast to, say, advertising, which is under the complete control of the advertiser. Companies that engage their customers in dialogues, in other words, must be prepared for many different outcomes.

- A dialogue with an individual customer will change an enterprise’s behavior toward that individual and change that individual’s behavior toward the enterprise. An enterprise should begin to engage in a dialogue with a customer only if it can alter its future course of action in some way as a result of the dialogue.

- A dialogue should pick up where it last left off. This is what gives a relationship its “context” and what can cement the customer’s loyalty. If prior communication between the enterprise and the customer has occurred, it should continue seamlessly, as if it had never ended.2

Implicit and Explicit Bargains

Conducting a dialogue with a customer is having an exchange of thoughts; it’s a form of mental collaboration. It might mean handling a customer inquiry or gathering background information on the customer. But that is only the beginning. Many customers are simply not willing to converse with enterprises. And rare is the customer who admits that she enjoys receiving an unsolicited sales pitch or telemarketing phone call. For an enterprise to engage a customer in a productive, mutually beneficial dialogue, it must conduct interesting conversations with an individual customer, on his terms, learning a little at a time, instead of trying to sell more products every time it converses with him.

If the customer-strategy enterprise is to remain a dependable collaborator with its customers, then it must not adopt a self-oriented attitude (see Chapter 2, which emphasizes the importance to the enterprise of not being self-oriented in its approach to customer relationships). Instead of sales-oriented commercials and interruptive, product-oriented marketing messages, the customer-strategy enterprise will use interactive technologies to provide something of value to the customer. By providing this value, the enterprise is inviting the customer to begin and sustain a dialogue. The resulting feedback increases the scope of the customer relationship, which is critical to increasing the enterprise’s share of that customer’s business.

For example, think about television. When advertisers sponsor a television program, they are in effect making an implicit bargain with viewers: “Watch our ad and see the show for free.” During television’s early decades, these implicit bargains made a lot of sense, because viewers had only a few other channels to choose from and no remote control to make it easy to change the channel. In the early days, everybody watched commercials. But as choices of content proliferated, the problem for marketers was that, because the traditional broadcast television medium has been nonaddressable,3 there has been no real way to tie the particular consumer who watches the television show back to the ad or to know whether she saw it in the first place. There is also no real incentive, usually, for the consumer even to watch the ad, since with DVR or TiVo, she can just avoid it.

But today’s television viewer lives in a vastly different environment. Not only are there hundreds of channels from which to choose, but people are also watching television more selectively, with instant—and constant—control. Audiences have the power to tune out commercials at their will or even to block out the advertisements altogether. And video delivered via Internet connections is beginning to replace the traditional broadcast model, as more and more consumers are downloading full-length movies and television programs and wirelessly pushing them to their large-screen television monitors for viewing. Interactive TV has arrived and it’s on a variety of devices. Only two decades ago, more households in the United States had a TV than had a refrigerator, but now, 5 million homes in America, and the number is growing fast, are “zero TV” households—that is, they have given up cable and satellite connections in favor of streaming content. Tens of millions more combine traditional and streaming, and may eventually cut the cable cord. In streaming households and many cable and satellite households, directing interactive personalized ads to a particular viewer is a real capability.4 These technological trends are driven not just by innovation but by intense consumer demand for choice and immediacy.

However, interactive communications technologies are two-way and individually addressable. Because of these attributes, interactive media equip marketers with the tools to make “explicit” bargains rather than “implicit” ones with their consumers. They can interact, one to one, directly with their individual media customers. An explicit bargain is, in effect, a “deal” that an enterprise makes with an individual to secure the individual’s time, attention, or feedback. Dialogue and interaction have such important roles to play, in terms of improving and enhancing a relationship, that often it is useful for an enterprise actually to “compensate” customers, in the form of discounts, rebates, or free services, in exchange for the customer participating in a dialogue.

The interactive world is chock full of examples of explicit bargains. Hundreds of Web site operators around the globe, from Facebook to Google, offer free digital services to customers who are agreeable to receiving advertising messages or facilitating the delivery of ad messages to others. Some of the ads are highly targeted, and even based on the content of the e-mail messages themselves. For example, if a Gmail user writes a personal message to a friend discussing, say, a trip to the Bahamas, Google will likely show banner ads on the e-mail page that promote air travel, vacation packages, or hotels. Marketers routinely buy “keywords” from Internet search engines, so that when a consumer searches for, say, “flat-screen televisions,” the marketer’s own ad will appear prominently within the search results. It is standard practice for a Web site operator to require a visitor to register, providing personal identifying data and preferences, in return for gaining access to the site’s more detailed information or automated tools.

Do Consumers Really Want One-to-One Marketing?

Imagine a study that asks customers whether they like the idea of tailored ads and personalized news. The problems with such a survey should be obvious: First, people really don’t like advertising and marketing messages in general. (Is that a surprise to anyone?) Of course, they don’t want tailored advertising, but they don’t want untailored advertising either.5 Imagine if a study asked this question instead:

Please tell me whether you would prefer the Web sites you visit to show you ads tailored to your interests or, instead, to charge you a small fee for viewing the Web sites.

And, of course, we all know what the answer to that question would be. You don’t need a survey to demonstrate it, because the history of the Web already makes it very clear that free, ad-supported content will triumph over paid content at least 90 percent of the time.

But, second, any rookie market researcher can tell you that consumers who are asked generalized questions like this often have difficulty visualizing the actual situation. The right way to have asked this question would have been to demonstrate it to the consumer directly. For instance, prior to asking these questions, what if the interviewer had first asked:

Please tell me whether you prefer diet drinks or nondiet drinks.

And then they could ask:

Please tell me whether you would prefer the Web sites you visit to show you ads for diet drinks or for nondiet drinks? (Pick one.)

There is still, however, a very important lesson to be drawn from this discussion: the fact that consumers don’t see any benefit to tailoring is an indictment of most of us marketers, because we have done such a lame job of tailoring our messages and making them genuinely relevant to our customers. It is not surprising that ordinary consumers would have difficulty visualizing personalized advertising messages, because even today, with all the computer power and interactive technologies available to marketers, most consumers have very rarely witnessed personalized ads that are genuinely relevant!

Explicit bargains with consumers are certainly not confined to the Web either. One international survey discovered that online customers are not very aware of how and how much data about them is collected, but once they learn about it, they expect something in return. One example is product enhancement, such as when the Samsung Galaxy phone uses your calling information to populate your “Favorites” list automatically. Disney uses MagicBands in its parks as a way to swipe for room access, food payment, and preferred attraction access. Google’s virtual assistant can read the time in your calendar that you have an appointment and remind you to leave in time to make it.6

In an interactive medium, an advertiser can secure a consumer’s actual permission and agreement, individually. By making personal preference information a part of this bargain, the service can also ensure that the ads or promotions delivered to a particular subscriber are more personally relevant, in effect increasing the value of the interaction to the marketer by increasing its relevance to the consumer. Explicit bargains like this are good examples of what author Seth Godin calls “permission marketing” (a concept we discuss in more detail in Chapter 9), in which a customer has agreed, or given permission, to receive personalized messages.

Technology of Interaction Requires Integrating across the Entire Enterprise

Most business-to-business (B2B) companies already have active sales forces engaged in some form of relationship building with the accounts they serve, but new technologies allow them to automate a sales force to better ensure that customer interactions are coordinated among different players within an account and that the records of these interactions are captured electronically. For a business-to-consumer (B2C) company, however, interactive technologies enable it to create a consumer-accessible Web site, and to coordinate the interactions that take place on this Web site with the interactions that take place at the call center and at the point of sale and at any other point of contact with the customer. The universal question for such an enterprise, wrestling with how to use these technologies, is: What is the right communication or offer for this particular customer, choosing to interact with us at this time to use this technology?

The point is that the arrival of cost-efficient interactive technologies has pretty much forced companies in all industries, all over the world, to take a step back and reconsider their business processes entirely. To deal with interactivity, they must create new processes that are oriented around the coordination of all these newly possible customer interactions. And they must ensure that the interactions themselves not only run efficiently but are effective at building more solid, profitable relationships with customers.

Don Schultz, Stanley Tannenbaum, and Robert Lauterborn’s classic book, The New Marketing Paradigm: Integrated Marketing Communications,7 documented the problems that occur whenever a single customer ends up seeing a mishmash of uncoordinated advertising commercials, direct-mail campaigns, invoices, and policy documents, and made the case for consistent marketing communications across the entire enterprise. Today, sophisticated interactive technologies enable enterprises to ensure that their customer-contact personnel can remember an individual customer and his preferences. And so we have seen the field of customer communications evolve from “integrated” to “multichannel” to “omnichannel.” A company can use software that creates an “ecosystem” of data about its customers and cull information from all of the touch points where it interacts with customers—call centers, Web sites, social media, e-mail, and other places. If the enterprise can better understand its customers, it can better serve them by providing individually tailored offers or promotions and more insightful customer service.8 The result is that integrating the enterprise’s marketing communications is no longer a cutting-edge strategy but a must-have standard. In fact, it’s not preposterous to assume that going forward, the default marketing strategies will be digital and individualized, with a secondary effort in more traditional media.9

The enterprise has to integrate all of its customer-directed communication channels so that it can accurately identify each customer no matter how an individual customer or a customer company contacts the enterprise. If a customer called two weeks ago to order a product and then sent an e-mail yesterday to inquire about his order status, and then tweeted that he didn’t hear back from the company fast enough, the enterprise should be able to provide an accurate response for the customer quickly and efficiently. The company should remember more about the customer with each successive interaction. More important, as we said before, it should never have to ask a customer the same question more than once, because it has a 360-degree view of the customer, and “remembers” the customer’s feedback across the organization. The more the enterprise remembers about a customer, the more unrewarding it becomes to the customer to defect. The customer-strategy enterprise ensures that its interactive, broadcast, and print messages are not just laterally coordinated across various media, such as television, print, sales promotion, e-mail, and direct mail, but that its communications with every customer are longitudinally coordinated, over the life of that individual customer’s relationship with the firm.

Providing any kind of dialogue tool to customers enables the enterprise to secure deeper, more profitable, and less competitively vulnerable relationships with each of them. The deeper each relationship becomes, and the more it is based on dialogue, the less regimented that relationship will be. The customer may want to expand the dialogue on his own volition because he knows that each time he speaks to the enterprise, it will listen. Today, what most enterprises fail at is not the mechanics of interacting but the strategy of it—the substance and direction of customer interaction itself.

Companies that employ such integration of customer data and coordination of customer interaction develop reputations as highly competent, service-oriented firms with excellent customer loyalty. Dell Computer has used direct mail, e-mail, personal contact by sales representatives, and special access to what amounts to intranet Web sites for large Dell accounts to stay connected with those customers.10 JetBlue’s reputation for service11 has been burnished by its extremely good online interaction efficiency and the seamless connections that customers experience among the airline’s reservations, ticketing, baggage tracking, and flight operations systems. Walgreens pharmacy has merged traditional and new media by offering newsprint and online clippable coupons, pharmacists in-store, as well as a 24/7 chat line to a pharmacist over a mobile app. Additionally, customers can refill a prescription in-store or scan the prescription label with a mobile app.12 Fast Company credited Walgreens’ omnichannel presence as one of the reasons the company was named one of the Top Ten health care companies for 2013.13

Over time, a customer who interacts with a competent customer-strategy enterprise will come to feel that he is “known” by the enterprise. When he makes contact with the enterprise, that part of the organization—whether it is a call rep or a service counter or any other part of the firm—should have immediate access to his customer information, such as previous shipment dates, status of returns or credits, payment information, and details about the last discussion. A customer does not necessarily want to receive more information from the enterprise; rather he wants to receive better, more focused information—information that is relevant to him, individually.

Integrating the interactions with a customer across an entire enterprise requires the enterprise to develop a solid understanding of all the points at which a customer “touches” the firm. Stated another way, the customer-strategy enterprise needs to be able to see itself through the eyes of its customers, recognizing that those customers will be experiencing the enterprise in a variety of different situations, through different media, dealing with different systems, and using different technologies. Mapping out these touch points is one of the first tasks many customer-strategy enterprises choose to undertake, and one comprehensive process for accomplishing the task is outlined in the next section by Mounir Ariss, a former managing partner at Peppers & Rogers Group.

Customer Dialogue: A Unique and Valuable Asset

Interaction with a customer, whether it is facilitated by electronic technologies or not, requires the customer to participate actively. Interaction also has a direct impact on the customer, whose awareness of the interaction is an indispensable part of the process. Since interaction is visible to customers, interacting customers gain an impression of an enterprise interested in their feedback. It is a vital part of the customer experience with the brand or the enterprise. The overarching objective on the part of the enterprise should be to establish a dialogue with each customer that will generate customer insight—insight the enterprise can turn into a valuable business asset, because no other enterprise will be able to generate that insight without first engaging the customer in a similar dialogue.

This is one of the key benefits of the Learning Relationship we’ve been discussing, and it is based on the fact that different customers want and need different things. This means we also should expect different customers to prefer different interaction methods. One customer prefers e-mail to phone; another likes a combination of e-mail and regular mail; still another only visits social networking sites, such as Twitter. The level of personalization that the Web affords to a customer also should be available in more traditional “customer-facing” venues. Retail sales executives in the store, for instance, should have access to the same knowledge base of customer information and previous interactions and transactions with the enterprise as a customer service representative (CSR) at corporate headquarters, customer interaction centers, or customer contact centers. Enterprises must be able to identify which channels each of their customers prefers and then decide how they will support seamless interactions. Those enterprises that fail to provide these interaction capabilities can lose sales and compromise relationships.14

The goal for the customer-strategy enterprise is not just to understand a market through a sample but also to understand each individual in the population through dialogue. The dialogue information that is of most interest to the enterprise falls into two general categories:

- Customer needs. The best method for discovering what a customer wants is to interact with him directly. Each time he buys, the enterprise discovers more and more about how he likes to shop and what he prefers to buy. Interactions are important not only because the customer is investing in the relationship with the enterprise, but also because the enterprise learns substantive information about the customer that a competitor may not know. Interaction gives the enterprise valuable information about a customer that a competitor cannot act on.

- Potential value. With every customer interaction, customers help the enterprise estimate more accurately their trajectory and their actual value to the enterprise. Getting a handle on a customer’s potential value, however, is often problematic. Through dialogue, a customer might reveal more specific plans or intentions regarding how much money she will spend with the enterprise or how long she will use its products and services. Insight into a customer’s potential value could include, among other things, advance word of an upcoming project or pending purchase; information with respect to the competitors a customer also deals with; or referrals to other customers that could be profitably solicited by the enterprise. This type of information is not usually available from a customer’s buying history or transactional records and can be obtained only through direct interaction and dialogue with the customer.

Because most customers will not sit still for extensive questioning at any given touch point, the successful customer-oriented enterprise will learn to use each interaction, whether initiated by the customer or the firm, to learn one more incremental thing that will help in growing share of customer (SOC) (see Chapter 1) with that customer. This is the concept we call drip irrigation dialogue. USAA Insurance in San Antonio, Texas, calls it smart dialogue. As the basis for intelligent interaction, USAA uses business rules within its customer data management effort to a make a customer’s immediate history available to its CSRs as soon as a customer calls. The CSRs also see a box on their computer screens that state the next question USAA needs to have answered about a customer in order to serve him better. This is not a question USAA is asking every customer who calls this month; it is the next question for this customer.

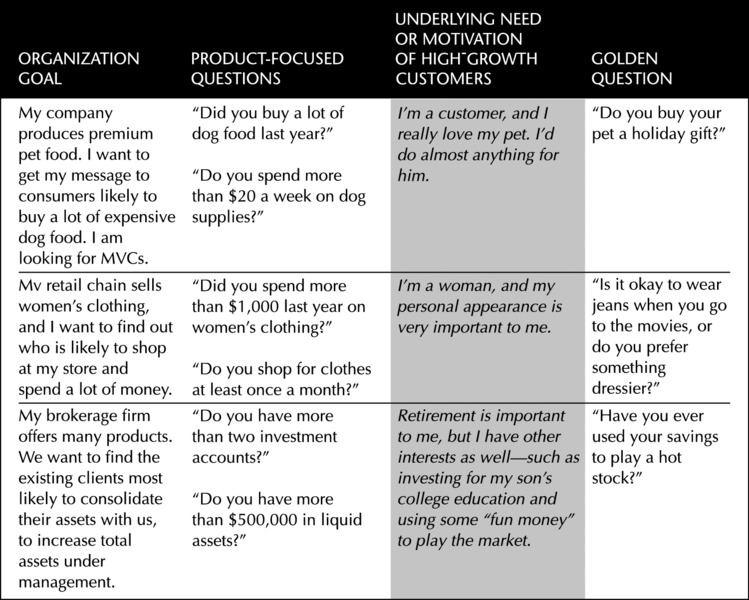

In many cases, an enterprise will use Golden Questions to understand its customers and thus achieve needs and value differentiation quickly and effectively (see Chapters 5 and 6). Golden Questions are designed to reveal important information about a customer while requiring the least possible effort from the customer. Designing a Golden Question almost always requires a good deal of imagination and creative judgment, but the question’s effectiveness is predetermined by statistically correlating the answers with actual customer characteristics or behavior, using predictive modeling. In general, an enterprise should avoid most product-focused questions, except in situations in which the customer is trying to specify a product or service, prior to purchase. Instead, the most productive type of customer interaction is that which reveals information about an individual customer’s underlying need or potential value. To better understand how product-focused questions differ from Golden Questions, examine the hypothetical chart in Exhibit 7.1.

Exhibit 7.1 Development of Golden Questions

Not All Interactions Qualify as “Dialogue”

Many interactions with customers are simply not welcomed by the customer. In fact, a large portion of customer-initiated interactions with businesses occur because something has gone wrong with a product or service, and the customer needs to contact the enterprise to try to get things put right. It can be frustrating in the extreme for a customer to try to navigate through a complex IVR in order to get a problem resolved, only to realize later that the problem was not resolved and they need to contact the company again. Companies need to become one-stop shops when it comes to complaint handling. Only 21 percent of complaining customers say they felt their problems were resolved on the first contact, and that it was not unusual to need four or more contacts to get things resolved.15 In other words, things work just fine until they don’t, and then the poor customer has to really work hard—without being on the payroll—to get what she should have had just for doing business with a company. One of the best books on managing contact-center interactions with customers is The Best Service Is No Service: How to Liberate Your Customers from Customer Service, Keep Them Happy, and Control Costs.16 Author Bill Price is the former vice president of Global Customer Service at Amazon.com, certainly a sterling example of a highly competent customer-strategy enterprise, and coauthor David Jaffe is a consultant in Australia, focused on helping companies manage their customer experiences. The whole point is that customers hate having to make complaint calls, so doing things right to begin with offers a far better experience for customers than any kind of special treatment from the “customer service” department. In this excerpt from The Best Service Is No Service, the authors consider all the ways customers can be simply annoyed at the necessity of contacting the companies they buy from and interacting with them.

Tapping into feedback from customers is an immensely powerful tactic for improving a company’s sales and marketing success. But customers will share information only with companies they trust not to abuse it. (See Chapter 9 for more on privacy issues.) Here are some ways to earn this trust, encouraging customers to participate more productively, improving both the cost efficiency and the effectiveness of customer interactions:

- Use a flexible opt-in policy. Many opt-in policies are all-or-nothing propositions, in which customers must elect either to receive a flood of communications from the firm, or none at all. A flexible opt-in policy will allow customers to indicate their preferences with regard to communication formats, channels, and even timing. To the extent possible, give customers a choice of how much communication to receive from you, or when, or under what conditions.

- Make an explicit bargain. Customers have been used to getting news and entertainment for free, in exchange for being exposed to ads or other commercial messages. As customers gain more power to zap commercials, eliminate pop-ups, and avoid unwanted calls, text messages, and e-mail they consider to be spam, marketers who want to talk to customers may need to make an explicit offer, something like this: Click here to receive e-mail offers from us in the future and save 20 percent on this order.

- Tread cautiously with targeted Web ads. Even though targeted online ads are popular with marketers, research has shown that consumers are especially wary of sharing information when targeted Web ads are the result. This doesn’t mean don’t do it, but it does mean don’t pile on. In any case, for behavioral targeting to succeed, an enterprise must have the customer’s informed consent.

-

Make it clear and simple. Have a clear, readable privacy policy for your customers to review. Procter & Gamble (P&G) provides a splendid example. Instead of posting a lengthy document written in legalese, P&G presents a one-page, easy-to-understand set of highlights outlining the policy, with links to more detailed information. Other companies are catching up. Five years ago, in its online offer to consumers to join the “My Sears Holding Community,” the company had a scroll box outlining the privacy policy that was just 10 lines of text but requires you to read 54 boxfuls to get through the whole policy. Buried far into the policy is a provision that lets the firm install software on your computer that “monitors all of the Internet behavior that occurs on the computer.”17 Now, though, the Sears privacy policy is written in pretty clear language and is organized in a more understandable way.18

- Create a culture based on customer trust. Emphasize the importance of privacy protection to everyone who handles personally identifiable customer information, from the chief executive officer to contact center workers. Line employees provide the customer experiences that matter, and employees determine whether your privacy policy becomes business practice or just a piece of paper. If your business culture is built around acting in the interest of customers at all times, then it will be second nature at your company to protect customers from irritating or superfluous uses of their personal information—things most consumers will regard as privacy breaches, whether they formally “agreed” to the data use or not.

- Remember: You’re responsible for your partners, too. It should go without saying that whatever privacy protection you promise your customers, it has to be something your own sales and channel partners—as well as your suppliers and other vendors—have also agreed to, contractually. Anyone in your “ecosystem” who might handle your own customers’ personally identifiable information and feedback will have the capacity to ruin your own reputation. Take care not to let that happen!

If an enterprise wants to conduct dialogues with customers, it must remember that the customers themselves must want to engage in these dialogues. Simply contacting a customer, or having the customer contact the enterprise, does not constitute dialogue, and will likely convey no marketing benefit to the enterprise.

Cost Efficiency and Effectiveness of Customer Interaction

Regardless of how automated they are, every interaction with a customer does cost something, if only in terms of the customer’s own time and attention, and some interactions cost more than others. The cost of customer interaction can be minimized partly by reducing or eliminating the interactions that the customer does not want. But ranking customers by their value also allows a company to manage the customer interaction process more cost efficiently. A highly valuable customer is more apt to be worth a personal phone call from a manager while a not-so-valuable customer’s interaction might be handled more efficiently on the Web site. An enterprise requires a manageable and cost-efficient way to solicit, receive, and process the interactions with its customers. It will need to categorize customer inquiries and responses in some effective way so it can customize its interactions for each customer.

Customer-strategy enterprises concentrate not just on the efficiency of the communication channel used for interactions with the customer but also on the effectiveness of the customer dialogue itself. Measuring efficiency might include tracking the percent of inbound customer inquiries satisfactorily answered by the enterprise’s Web site FAQ section, or monitoring how long customers stay on hold with the customer service department before they disconnect. Measuring effectiveness might include tracking first-call resolution (FCR), or the ratio of complaints handled or problems resolved on the first call. (Consider: Which kinds of measures for a call center—effectiveness or efficiency—will likely lead to better customer experiences and higher trust scores?) Critical to the success of any dialogue, however, is that each successive interaction with the individual customer be seen as part of a seamless, flowing stream of discussion. Whether the conversation yesterday took place via mail, phone, the Web, or any other communication channel, the next conversation with the customer must pick up where the last one left off.

For decades now, technology has been dramatically reducing the expenses required for a business to interact with a wide range of customers. Enterprises can now streamline and automate what was once a highly manual process of customer interaction. Different interactive mechanisms can yield widely different information-exchange capabilities, such as speed trackability, tangibility (the ability to hold it or refer back to it later), and personalization. Interacting regularly with a customer via a Web site is usually highly cost efficient and can be customer driven, yielding a rich amount of information. Postal mail is not as practical for dialogue, because it involves a lengthy cycle time, although it can prove effective for delivering more detailed information to the customer who prefers to keep hard copies. Telephone interaction has the advantages of real-time conversation, but neither phone nor face-to-face interaction facilitates easy tracking of the content of these conversations, and the enterprise trying to employ voice interactions to strengthen its customer relationships must be sure the employees responsible for the interactions are diligently and accurately capturing the key elements of customer dialogues (although scripted phone calls can aid in this effort).

Complaining Customers: Hidden Assets?

Customers generally contact an enterprise of their own volition for only three reasons: to get information, to obtain a product or service, or to make a suggestion or a complaint. Despite the fact that technology should make it easier for customers to contact companies, the Technical Assistance Research Program (TARP) found that customer complaints are declining – not because there are fewer problems but likely because, unfortunately, customers have been trained to expect problems as part of the cost of doing business.19 TARP discovered that 50 percent of customers with high-value problems would not complain at all, and that number rose to 96 percent for low-value items. Of the B2B customers who have a problem and do not complain, 90 percent will simply take their business somewhere else.20 But sometimes a complaint can provide an opportunity for real dialogue.

Thus, one way to view a complainer is to see him as a customer with a current “negative” value that can be turned into positive value. In other words, a complainer has extremely high potential value. If the complaint is not resolved, there is a high likelihood that the complaining customer will cease buying, and will probably talk to a number of other people about his dissatisfaction, causing the loss of additional business. But the potential for increased value; for one thing, the customer cares enough to, at least, contact the company to complain. The customer-oriented enterprise, focused on increasing the value of its customer base, will see a customer complaint as an opportunity to convert the customer’s immense potential value into actual value, for three reasons:

- Complaints are a “relationship adjustment opportunity.” The customer who calls with a complaint enables the enterprise to understand why their relationship is troubled. The enterprise then can determine ways to fix the relationship.

- Complaints enable the enterprise to expand its scope of knowledge about the customer. By hearing a customer’s complaint, the enterprise can learn more about the customer’s needs and strive to increase the value of the customer.

- Complaints provide data points about the enterprise’s products and services. By listening to a customer’s complaint, the enterprise can better understand how to modify and correct its generalized offerings, based on the feedback.

To a customer-centered enterprise, complaining customers have a collaborative upside, represented by a high potential value. In fact, they might have the highest potential value: Research from TARP has shown that the most loyal customers are the ones most likely to take the time to complain to a company in the first place. It has also found that customers who are satisfied with the solution to a problem often exhibit even greater loyalty than do customers who did not experience a problem at all.21

Because the handling of complaints has so much potential upside, a one-to-one enterprise will not avoid complaints but instead will seek them out. An effort to “discover complaints”—to seek out as many opportunities for customer dialogue as possible—becomes part of dialogue management. Complaint discovery contacts typically ask two questions:

- Is there anything more we can do for you?

- Is there anything we can do better?

At one European book club, for example, customer service representatives called new members during their first month and asked one simple question: “Is there anything we can do better?” No sales pitch or special promotion has been discussed. The results of this customer satisfaction initiative speak volumes to its effectiveness in retaining customers: nearly an 8 percent increase in sales per member, and 6 percent fewer dropoffs after the first year of membership, among those contacted.

Of course, today many of the “complaints” don’t need to be discovered. Now that it’s so much easier to tweet a problem, give a low product rating online, or reach a rep easily by chat on computer or mobile, companies are in a position where they can spend less time seeking complaints and more time resolving them.

Here’s the point: By complaining, a customer is initiating a dialogue with an enterprise and making himself available for collaboration. The enterprise focused on building customer value will view complaining customers as an asset—a business opportunity—to turn the complainers into loyal customers. That is why enterprises need to make it easy for a customer to complain when he needs to.

For their part, most customers see complaint discovery, or having an easy way to get problems solved, as a highly friendly and service-oriented action on the part of a firm. One survey commissioned by an auto dealer discovered that for the vast majority of the 6,500 automobile owners included in the survey, the very act of asking for their opinions made them into happier and more loyal (i.e., more valuable) customers. Customers who received a phone call simply asking about their opinion tended to become more satisfied with the automobile dealer than those who did not receive a call.

Summary

At this point, we’ve shown with this chapter the importance of customer interaction in the Learning Relationship. The enterprise that creates a sustained dialogue with each customer can learn more about that customer and begin to develop ways to add value that spring from learning about that customer and consequently to creating a product/service bundle that he is most interested in owning or using. And, like drip irrigation, which never overwhelms or parches, a sustained dialogue helps a company get smarter and serves the customer better than sporadic random sample surveys. The customer-based enterprise engages in a collaborative dialogue with each customer in that customer’s preferred channel of communication—whether it is the customer interaction center, e-mail, the phone, wireless, the Web, snail mail, or media we haven’t thought of yet.

The development of social media, however, has revolutionized a company’s capacity to interact with its customers—and its customers’ capacity to broadcast their experiences with a company, both good and bad. In the next chapter, we discuss how these different communication channels can help facilitate customer interaction and relationships with customers in general.

Food for Thought

- TiVo and other digital recording devices collect very specific data about household television viewing. These services make it possible to know which programs are recorded and watched (and when and how many times), which programs are recorded and never watched, and which programs are transferred to another electronic format. The services also know when a particular part of a program is watched more than once (a sports play, or a favorite cartoon, or movie scene, or even a commercial). What are the implications of that knowledge for dialogue? For privacy? For the business collecting the data (i.e., data or a cable company)? How might TiVo or a cable company use this information to increase the value it offers to advertisers and marketers? What would a marketer have to do differently to make the most of this information? How can DVR companies protect their own customers’ privacy? What happens next in this industry as a growing number of consumers cut their cable connections?

- What problems might occur if an enterprise participates in customer dialogues but its own information and data systems are not integrated well? Do you remember any personal experience in dealing with a company or brand that could not find the right records or information during your interaction with it? How did this make you feel about the company? Did you feel the company was less competent? Less trustworthy?

- What are some of the explicit bargains companies have made with you in your role as a customer to get some of your time, attention, or information?

- How does the European book club mentioned in the discussion of complaint discovery actually know that it’s the calling program that led to 6 percent fewer dropoffs and 8 percent more sales per member? Might it not have been the book selection that year? Or the economy?

- When you plan to buy a product and want to investigate its benefits and drawbacks, whose advice do you seek? Do you think the advertiser will tell you about the drawbacks, or just the benefits? If you are trying to evaluate the product by researching it online, do you have more confidence in it if the seller makes other customers’ reviews available? What if you read a negative comment? Might you still buy the product?

Glossary

- Actual value

- The net present value of the future financial contributions attributable to a customer, behaving as we expect her to behave—knowing what we know now, and with no different actions on our part.

- Addressable

- Refers to media that can send and customize messages individually.

- Business process reengineering (BPR)

- Focuses on reducing the time it takes to complete an interaction or a process and on reducing the cost of completing it. BPR usually involves introducing quality controls to ensure time and cost efficiencies are achieved.

- Business rules

- The instructions that an enterprise follows in configuring different processes for different customers, allowing the company to mass-customize its interactions with its customers.

- Complaint discovery

- An outbound interaction with a customer, on the part of a marketer, to elicit honest feedback and uncover any problems with a product or service in the process.

- Critical data elements (CDEs)

- High-level information flows that facilitate decision making and process execution.

- Customer contact center

- The functional corporate department or unit charged with the task of receiving, understanding, and dealing with individual customer inquiries and requests, using phone, chat, video, or other communication technologies. Contact centers were formerly known as call centers because the only practical way for customers to contact and interact with a company without visiting a store and doing so in person was by phone.

- Customer Interaction and Experience Touchmap

- A graphical depiction of the interactions a company has with each segment of its customers across each of the available channels. Its purpose is to take an outside-in view of the customer interactions, instead of the traditional inside-out view typically taken in business process reengineering work. Current State Touchmaps depict all the enterprise’s current interactions with customers and identify gap areas; Future State Touchmaps depict the desired customer interactions that will be customized based on the needs and values of individual customers.

- Customer interaction center

- See Customer contact center.

- Customer journey mapping

- A process of diagramming all the steps a customer takes when engaging with a company to buy, use, or service its product or offering. Also called customer experience journey mapping.

- Customer life cycle

- The “trajectory” a customer follows, from the customer’s first awareness of a need, to his or her decision to buy or contract with a company to meet that need, to use the product or service, to support it with an ongoing relationship, perhaps recommending it to others, and to end that relationship for whatever reason. The term customer life cycle does not refer to the customer’s actual lifetime or chronological age but rather to the time during which the product is in some way relevant to the customer.

- Customer service

- Customer service involves helping a customer gain the full use and advantage of whatever product or service was bought. When something goes wrong with a product, or when a customer has some kind of problem with it, the process of helping the customer overcome this problem is often referred to as customer care.

- Customer service representative (CSR)

- A person who answers or makes calls in a call center (also called a customer interaction center or contact center, since it may include online chat or other interaction methods). Sometimes called a “rep,” or representative.

- Customer-strategy enterprise

- An organization that builds its business model around increasing the value of the customer base. This term applies to companies that may be product oriented, operations focused, or customer intimate.

- Customize

- Become relevant by doing something for a customer that no competition can do that doesn’t have all the information about that customer that you do.

- Differentiate

- Prioritize by value; understand different needs. Identify, recognize, link, remember.

- Digital video recorder (DVR)

- A digital recording device (such as TiVo) that uses a hard disk drive to record programming content from cable or other input for use at the time desired by the customer user. Often uses interfaces (such as an on-screen program guide) that are regularly downloaded to the device.

- Drip irrigation dialogue

- An enterprise’s sustained, incremental dialogue that uses each interaction, whether initiated by the customer or by the firm, to learn one more incremental thing that will help in growing share of customer with that customer.

- Explicit bargain

- One-to-one organizations give something of value to a customer in exchange for that customer’s time and attention, and perhaps for information about that customer as well. An example: discounts on prices bought at a store where a customer shows his membership card.

- First-call resolution (FCR)

- When customer complaints are resolved at their first interaction with a company, whether it is through telephone, e-mail, or any other method of interaction. The measurable benchmark for customer service.

- Golden Questions

- Questions designed to reveal important information about a customer while requiring the least possible effort from the customer, in order to differentiate customer needs and potential value. The most productive Golden Questions will be customer need based rather than product based.

- Identify

- Recognize and remember each customer regardless of the channel by or geographic area in which the customer leaves information about himself. Be able to link information about each customer to generate a complete picture of each customer.

- IDIC

- Stands for Identify-Differentiate-Interact-Customize.

- Implicit bargain

- Advertisers have in the past bought ads that pay for the cost of producing the media that consumers want—television programming, newspaper copy, magazine stories, music on the radio, and so on. The implied “deal” was that consumers would listen to the ads in exchange for getting the media content free.

- Interact

- Generate and remember feedback.

- Interactive voice response (IVR)

- Now a feature at most call centers, IVR software provides instructions for callers to “push ‘1’ to check your current balance, push ‘2’ to transfer funds,” and so forth.

- Internet of Things (IoT)

- A term describing the network of products and other objects that have intelligence or computational capability built into them, along with interconnectedness to the Web, via Wi-Fi, or other technology. As defined by the ITU, a UN agency, the IoT is “a global infrastructure for the information society, enabling advanced services by interconnecting (physical and virtual) things based on existing and evolving interoperable information and communication technologies” (http://www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/gsi/iot/Pages/default.aspx, accessed April 6, 2016).

- Mutuality

- Refers to the two-way nature of a relationship.

- Needs

- What a customer needs from an enterprise is, by our definition, synonymous with what she wants, prefers, or would like. In this sense, we do not distinguish a customer’s needs from her wants. For that matter, we do not distinguish needs from preferences, wishes, desires, or whims. Each of these terms might imply some nuance of need—perhaps the intensity of the need or the permanence of it—but in each case we are still talking, generically, about the customer’s needs.

- Nonaddressable

- Refers to media that cannot send and/or customize messages individually.

- Omnichannel marketing

- A marketing buzzword referring to the capability of interacting and transacting with customers in any or all channels, in order to ensure that every interaction takes place in the channel of the customer’s own choice.

- Share of customer (SOC)

- For a customer-focused enterprise, share of customer is a conceptual metric designed to show what proportion of a customer’s overall need is being met by the enterprise. It is not the same as “share of wallet,” which refers to the specific share of a customer’s spending in a particular product or service category. If, for instance, a family owns two cars, and one of them is your car company’s brand, then you have a 50 percent share of wallet with this customer, in the car category. But by offering maintenance and repairs, insurance, financing, and perhaps even driver training or trip planning, you can substantially increase your “share of customer.”

- Social media

- Interactive services and Web sites that allow users to create their own content and share their own views for others to consume. Blogs and microblogs (e.g., Twitter) are a form of social media, because users “publish” their opinions or views for everyone. Facebook, LinkedIn, and MySpace are examples of social media that facilitate making contact, interacting with, and following others. YouTube and Flickr are examples of social media that allow users to share creative work with others. Even Wikipedia represents a form of social media, as users collaborate interactively to publish more and more accurate encyclopedia entries.

- Trajectory

- The path of the customer’s financial relationship through time with the enterprise.