Chapter 5

Differentiating Customers: Some Customers Are Worth More Than Others

The result of long-term relationships is better and better quality, and lower and lower costs.

—W. Edwards Deming

Identifying each customer individually and linking the information about that customer to various business functions prepares the customer-strategy enterprise to engage each customer in a mutual collaboration that will grow stronger over time. The first step is to identify and recognize each customer at every touch point. As we saw in Chapter 4, when the “identify” task is properly executed, information about individual customers should allow a company to see each customer completely, as one customer, throughout the organization. And seeing customers individually will enable the company to compare them—to differentiate customers, one from another. By understanding that one customer is different from another, the enterprise reaches an important step in the development of an interactive, customer-centric Learning Relationship with each customer.

The inability to see customers as being different does not mean the customers are the same in needs or value, only that the firm sees them that way. Understanding, analyzing, and profiting from individual customer differences are tasks that go to the very heart of what it means to be a customer-strategy or customer-centric enterprise—an enterprise that engages in customer-specific behaviors, in order to increase the overall value of its customer base.

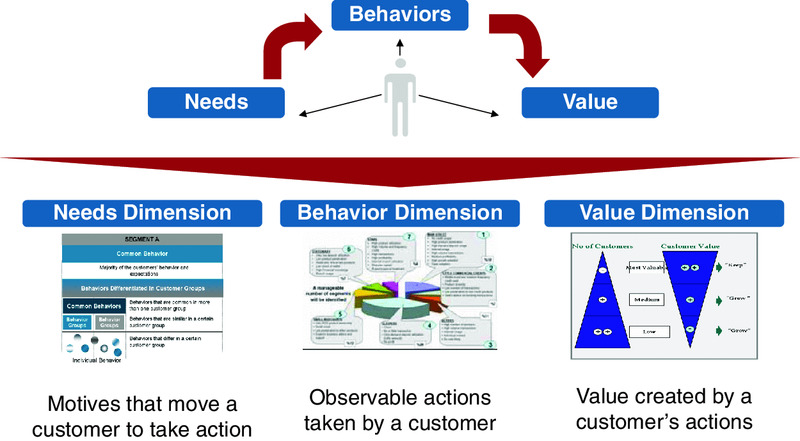

Customers are different in two principal ways: Different customers have different values to the enterprise, and different customers have different needs from the enterprise. The entire value proposition between an enterprise and a customer can be captured in terms of the value the customer provides for the firm and the value the firm provides for the customer (i.e., what needs the firm can meet for the customer). All other customer differences, from demographics and psychographics, to behaviors, transactional histories, and attitudes, represent the tools and concepts marketers must use simply to get at these two most fundamental differences. Behaviors are in some instances the most observable, and thus the ability of a company to track differences in customer behaviors allows deeper understanding, and for that reason, we talk about differentiating customers by the value they have to the company, the needs they have from the company, and the behaviors they manifest that help us understand value and needs, as illustrated in Exhibit 5.1.

Exhibit 5.1 Treating Different Customers Differently

Knowing which customers are most valuable and least valuable to the enterprise will enable a company to prioritize its competitive efforts, allocating relatively more time, effort, and resources to those customers likely to yield higher returns. In effect, an enterprise’s financial objectives with respect to any single customer will be defined by the value the customer is currently creating for the enterprise (her actual value) as well as the potential value the customer could create for the enterprise, if the firm could present the exact right offerings at the right time as needed by the customer and thus change the customer’s behavior in a way that works for both the customer and the enterprise. Of course, changing a customer’s behavior (which is the basic objective of all marketing activity) can be accomplished only by appealing to the customer’s own personal motives, or needs. So while understanding a customer’s value profile will determine a firm’s financial objectives for that customer, the strategies and tactics required to achieve those objectives require an understanding of that customer’s needs. It should be noted that a customer has value to the enterprise in two ways that matter to shareholders and decision makers: A customer has current value (revenue minus cost to serve) as well as long-term value in the present that goes up or down based on experience with the company or brand, influence from the outside, and changes in his own needs.

In this chapter, we discuss the concept of customer valuation, including various ways a company might rank its customers by their individual values to the enterprise. In Chapter 6, we address the issue of customer needs. Importantly, we return again and again throughout the book to these two issues: the different valuations and needs of different individual customers.

Customer Value Is a Future-Oriented Variable

Mail-order firms, credit card companies, telecommunications firms, and other marketers with direct connections to their consumer customers often try to understand their marketing universe by doing a simple form of prioritization called decile analysis—ranking their customers in order of their value to the company and then dividing this top-to-bottom list of customers into 10 equal portions, or deciles, with each decile comprising 10 percent of the customers. In this way, the marketer can begin to analyze the differences between those customers who populate the most valuable one or two deciles and those who populate the less valuable deciles. A credit card company may find, for instance, that 65 percent of top-decile customers are married and have two cards on the same account while only 30 percent of other, less valuable customers have these characteristics. Or a Web-based retailer may find that a majority of customers in the bottom three or four deciles have never before bought anything by direct mail or Internet or from a mobile device while 85 percent of those in the top two deciles have.

It would not be unusual for a decile analysis to reveal that 50 percent, or even 95 percent, of a company’s profit comes from the top one or two deciles of customers. Mail-order houses and other direct marketers are more likely than other marketers to have used decile analysis in the past, largely as a means for evaluating the productivity of their mailing campaigns, but this kind of customer ranking analysis will become increasingly important as more companies begin to adopt a customer focus.1

But just how does a company rank-order its customers by their value in the first place? What data would the credit card company use to analyze its customers individually and then array them from top to bottom in terms of their value? And what variables would go into the Internet retailer’s customer rankings? What do we mean when we talk about the value of a customer, anyway?

For our purposes, the value a customer represents to an enterprise should be thought of as the same type of value any other financial asset would represent. To say that some customers have more value for the enterprise than others is merely to acknowledge that some customers are more valuable, as assets, than others are. The primary objective of a customer-strategy enterprise should be to increase the value of its customer base, for the simple reason that customers are the source of all short-term revenue and all long-term value creation, by definition. In other words, a company should strive to increase the sum total of all the individual financial assets known as customers.

But this is not as simple as it might sound, because in the same way any other financial asset should be valued, a customer’s value to the enterprise is a function of the profit the customer will generate in the future for the enterprise.

Let’s take a specific example. Suppose a company has two business customers. Customer A generated $1,000 per month in profit for the enterprise over the past two years, while Customer B generated $500 in monthly profit during the same period. Which customer is worth more to the enterprise?

Knowing only what we’ve been told so far, we can say it’s probable that Customer A is worth more than Customer B, but this is not a certainty. If Customer A were to generate $1,000 in profit per month in all future months, while Customer B were to generate $500 per month in all future months, then certainly A is worth twice as much to the enterprise as B. But what if we know that Customer A plans to merge its operations into another firm in three months and switch to a different supplier altogether, while Customer B plans to continue doing its regular volume with the company for the foreseeable future? In that case, our ranking of these two customers would be reversed, and we would consider B to be worth more than A. However, if what actually happened was that a competitor derailed A’s merger while B went bankrupt and ceased all operations the following month, then our assessment would still be wrong.

By definition, a customer’s value to an enterprise, as a financial asset, is a future-oriented variable. Therefore, it is a quantity that can truly be ascertained only from the customer’s actual behavior in the future. We mortals can analyze data points from past behavior, we can interview a customer to try to understand the customer’s future opportunities and intent, and we can even conclude contractual agreements with customers to guarantee performance for the contract period, but the plain truth is that, without clairvoyant powers, we can’t know what a customer’s true value is until the future actually happens, even though we have better and better analytical tools to predict what will happen. (Despite the improvements in quantitative analysis available, one study discovered that less than half of all firms are able to measure customer lifetime value, thereby essentially closing off the ability to make optimum strategic decisions.)2

However, until that future does happen, we can affect its outcome—at least partially—by our own actions. Suppose we were to find a revenue stream for Customer B that allowed it to continue in business rather than going bankrupt. By our own deliberate action, in this case, we would have changed B’s value to our firm as a financial asset.

To think about customer valuation, therefore, we need to use two different but related concepts:

- Actual value is the customer’s value, given what we currently know or predict about the customer’s future behavior.

- Potential value is what the customer’s value as an asset to the enterprise could represent if, through some conscious strategy on our part, we could change the customer’s future behavior in some way.

Customer Lifetime Value

The “actual value” of a customer, as we defined it, is equivalent to a quantity frequently termed customer lifetime value (LTV). Defined precisely, a customer’s LTV is the net present value of the expected future stream of financial contributions from the customer.3 Every customer of an enterprise today will be responsible for some specific series of events in the future, each of which will have a financial impact on the enterprise—the purchase of a product, a blog post about the company, payment for a service, remittance of a subscription fee, a product rating on a Web retailing site, a product exchange or upgrade, a warranty claim, a help-line telephone call, the referral of another customer, and so forth. Each such event will take place at a particular time in the future and will have a financial impact that has a particular value at that time. The net present value (NPV), today, of each of these future value-creating events can be derived by applying a discount rate to it to factor in the time value of money as well as the likelihood of the event. LTV is, in essence, the sum of the NPVs of all such future events attributed to a particular customer’s actions.

One useful way to think about the different types of events and activities that different customers will be involved in is to visualize each customer as having a trajectory that carries the customer through time in a financial relationship with the enterprise. For example, a customer could begin his relationship at a particular starting point and at a particular spending level. At some point, he increases his spending, taking another product line from the company; later he also begins paying more for some added service. Still later he has a complaint, and it costs the company some expense to resolve it. He refers another customer to the company, and that customer then begins her own trajectory, creating a whole additional value stream. Eventually, perhaps several years or decades later, the original customer “leaves the franchise,” because his children grow up, or he decides to switch to another product altogether, or he gets divorced, or retires, or dies. At this point, his relationship with the enterprise comes to an end. (We could describe a business customer’s trajectory in the same way. Although a “business” may have an indefinite future potential as a customer, each of the individual potential end users, purchasing agents, influencers, and so forth eventually will quit, get promoted or transferred or fired, retire, or die.)

Different customers will have different trajectories. In a way, the lifetime value of each customer amounts to the NPV of the financial contribution represented by that customer’s trajectory through the customer base. From a customer’s stream of positive contributions, including product and service purchases, an enterprise must deduct the expenses associated with that customer, including the cost of maintaining a relationship. For instance, relationships usually require some amount of individual communication, via phone, mail, e-mail, or face-to-face meetings. These costs, along with any others that apply to a specific individual customer, will reduce the customer’s LTV. It sometimes happens that the costs associated with a customer actually outweigh the customer’s positive contributions altogether, in which case the customer’s LTV is below zero (BZ).

We are using the term contribution, as opposed to profit, deliberately, because the value of a particular customer is equivalent to the marginal contribution of that customer, when he is added to the business in which the enterprise is already engaged. Suppose we add up all the positive and negative cash flows an enterprise will generate over the next few years, and the total is $X. But then Customer A’s trajectory of financial transactions is removed from the enterprise, and the positive and negative cash flows will only amount to a lesser total of $Y. The customer’s marginal contribution is equal to X – Y. The NPV of those various contributions by Customer A is the customer’s LTV. There are additional “contributions” a customer can make, not all of them monetary. Aside from the obvious word of mouth (WOM) given by a customer, a nonprofit organization looks to volunteer work or other participation.

In practice, of course, it is not possible for an enterprise to know what any particular customer’s future contributions will actually be, and if we want to be able to make current decisions based on this future-oriented number, then we will have to estimate it in some way. Traditionally, the most reliable predictor of a customer’s future behavior has been thought to be that customer’s past behavior. We are usually quite justified in making the commonsense assumption that a customer who has generated $1,000 of profit each month for the last two years will continue to generate that profit level for some period of time in the future, even though we simultaneously acknowledge that any number of forces can appear that will change this simplistic trend at any moment. (That’s why so many of the researchers listed in footnote 3, and others, are hard at work looking for alternative and more accurate ways to predict a customer’s future value.) Various computational techniques can be used to model the probable trajectories of particular types of customers more precisely and to project these expected trajectories into the future. Some companies have customer databases that allow highly sophisticated modeling and analysis. Such analysis can sometimes be used to give an enterprise advance warning when a credit card customer, or a cell phone customer, or a Web site subscriber, is about to defect to a competitor. A whole class of statistical analysis tools, frequently termed predictive analytics, is designed to help businesses sift through the historic records of certain types of customers, in order to model the likely behaviors of other, similar customers in the future.

According to the late CRM consultant Frederick Newell, LTV models have a number of uses. They can help an enterprise determine how much it can afford to spend to acquire a new customer or perhaps a certain type of new customer. They can help a firm decide just how much it would be worth to retain an existing customer. With a model that predicts higher values for certain types of customers, an enterprise can target its customer acquisition efforts in order to concentrate on attracting higher-value customers. And, of course, the LTV measurement represents a more economically correct way to evaluate marketing investments compared to simply counting immediate sales.4

Although sophisticated modeling methods help to quantify LTV, many variables cannot be easily quantified, such as the assistance a customer might give an enterprise in designing a new product, or the value derived from the customer’s referral of another customer, or the customer’s willingness to advocate for the product or company on a social networking Web site. Any model that attempts to calculate individual customer LTVs should employ some or all of these data, quantified and weighted appropriately:

- Repeat customer purchases.

- Greater profit and/or lower cost (per sale) from repeat customers than from initial customers (converting prospects).

- Indirect benefits from customers, such as referrals. (Imagine that you are a book author and Oprah Winfrey bought and likes your book!)

- Willingness to collaborate—the customer’s level of comfort and trust with the company and participation in data exchange that results in the opportunity for better customer experience (sometimes called relationship strength).

- Willingness to refer—word of mouth—as well as social media sharing and rating

- Customers’ stated willingness to do business in the future rather than switch suppliers.

- Customer records.

- Transaction records (summary and detail).

- Products and product costs.

- Cost to serve/support.

- Marketing and transaction costs (including acquisition costs).

- Response rates to marketing/advertising efforts.

- Company- or industry-specific information.

The objective of LTV modeling is to use these and other data points to create a historically quantifiable representation of the customer and to compare that customer’s history with other customers. Based on this analysis, the enterprise forecasts the customer’s future trajectory with the enterprise, including how much he or she will spend, and over what period.

For our purposes, it is sufficient to know that:

- The actual value of a customer is the value of the customer as a financial asset, which is equivalent to the customer’s lifetime value—the NPV of future cash flows associated with that customer. (This is the current value, assuming business as usual.)

- LTV is a quantity that no enterprise can ever calculate precisely, no matter how sophisticated its predictive analytics programs and statistical models are.

- Nevertheless, even though—like many of the widely accepted “numbers” calculated to report business performance—it can never be precisely known, LTV is a real financial number, and every enterprise has an interest in understanding it as accurately as possible and positively affecting its customers’ LTVs to the extent possible, and—as we shall see in Chapter 13—to hold members of the organization responsible for exactly that.

As difficult as LTV and actual value may be to model, potential value is an even more elusive quantity, involving not just guesses regarding a customer’s most likely future behavior but guesses regarding the customer’s options for future behavior.

Still, potential value isn’t impossible to estimate, especially if the analysis begins with a set of customers who have already been assigned actual values or LTVs. Probably the most straightforward way to estimate a customer’s potential value is to look at the range of LTVs for similar customers and then to make the arbitrary assumption that in an ideal world it should at least be possible to turn lower-LTV customers into higher-LTV customers. In the consumer business, this means examining the LTVs for customers who are perhaps at the same income level, or have the same family size, or live in the same neighborhoods. For business-to-business (B2B) customers, it would mean comparing the LTVs of corporate customers in the same vertical industries, with the same sales levels, or profit, or employment levels, and so forth.

The problem at many companies is that a customer’s “value to the firm” is confused with the customer’s current profitability. Often, measuring customer profitability at all, even in the short term, is an achievement for a firm. But when a customer’s LTV is taken into account, the results will be more revealing, and estimating potential values will yield still more insight.

Recognizing the Hidden Potential Value in Customers

It is understandable that a firm’s marketing analysts may be reluctant to forecast future behaviors for a customer when they haven’t already observed and modeled those behaviors in the customer’s transactional history. But consider the idea that today’s customer might actually increase his or her patronage with a firm considerably, based solely on the fact that, as time goes on, the customer matures into an older and more productive person. Royal Bank of Canada (RBC)5 was one of the first banks to look carefully and analytically at the youth segment as a promising group of retail banking customers when most banks were overlooking this segment due to their low current (actual) value. RBC recognized the high potential value of young college students, many of whom would become highly paid professionals in the future. The bank gained a competitive advantage by reaching out to and building loyalty in this segment early on, even though their current value was low. In a similar way, certain groups of customers who are in a temporary financial slump, or even in bankruptcy, could have the potential to be promising and high-value customers in the future. A bank that identifies such customers (differentiating them from other customers who are bankrupt now and likely to remain in financial distress for the long term) and reaches out to them at this difficult stage in their lives is certain to win these customers’ loyalty and trust.

In telecommunications, some companies find hidden word-of-mouth power in the ranks of their currently low-value “public-sector employees” segment. For example, when Sprint once offered attractive rates and group discounts to this public-sector group, the word-of-mouth impact resulted in increased new customer acquisitions, increasing the company’s profitability and market share.6 A close look at the needs of the customers was of course an enabling step in this strategy, where the telecommunications company was able to find the rate, payment, or discount benefits that best suited the needs and payment behavior of this customer group. The benefits could easily have been missed, however, had this company looked solely at these customers’ historically based actual values.

Taking into account the “customer influence” factor in modeling lifetime value is even more critical in some industries where a small number of customers exert a disproportionate share of influence on others’ buying decisions, such as in the pharmaceuticals industry. The primary customers here, at least in most countries, are physicians, and some physicians almost always stand out for the amount of influence they have on the medical practices of other physicians. Identifying and trying to quantify the value of such “key opinion leaders” (KOLs) is a high priority for pharmaceutical companies, such as Abbott Labs, Bristol-Myers Squibb, and Biogen Idec.7 KOLs usually are viewed by their peers as experts in specific therapeutic areas, and as such they exert immense influence over other doctors when it comes to the types of medications to be prescribed and the kinds of medical treatments to be administered in these therapeutic areas. Even though some KOLs may have low actual values themselves, in terms of the prescriptions they write in their own medical practice, their influence is disproportionately valuable. Some pharmaceutical companies (e.g., Roche8) even try to identify rising KOL stars, who are for the most part relatively less well-known professionals who show signs of future success and influence. The companies then invite these rising stars to participate in medical education and other activities, hoping to build long-lasting relationships.

One industry in which potential value can be an important differentiator is the airline business. Because of their widely used frequent-flyer programs, airlines usually have a fairly good handle on the transactional histories of their most frequent travelers who are, for the most part, business flyers. But even if a business traveler flies 75,000 miles a year on an airline, the airline has no way of knowing, from its own transactional records, whether that traveler is flying another 150,000 miles on competitive carriers, and thus has a large potential value. So, in trying to estimate the potential value of an airline customer, it is critical to look at external data sources (and, in some cases, simply to ask a customer in order to get share-of-customer information) when such sources are available and perhaps to tap into the data available from distributor partners, such as travel websites or credit card firms. Lifestyle changes can also create shifts in the potential value of a customer and should be taken into account. Southwest Airlines, for example, identified and sent relevant offers to some currently low-value customers who moved to another country as expatriates, and these customers proved to have high potential value as evidenced by their future travels on holidays to their home country.

In addition to overlooking customers with high potential value, some companies make wrong and unprofitable investments in customers who seem to be high in value now but in fact have a low or sometimes negative potential value. In the retailer category, companies like Best Buy, Victoria’s Secret, and Home Depot9 have begun tracking customer returns for potential denial of repeat returners, preventing losses from this group who prove to be below zero customers over the long term.

Another company that avoided unnecessary investment in low-potential-value customers is Capital One Bank, which recognized its low-potential-value customers and adjusted its reactive retention strategy to deemphasize them. (After all, why should the company go out of its way to retain a low-value customer?) One variable that can reduce the potential value of a financial services customer is financial risk. Understanding the likelihood that a customer will need to be charged off in the future is an important function for any credit-granting institution. Capital One, while giving incentives and positive offers to its high-value customers who want to close their accounts in order to save them, encouraged the high-risk customers (i.e., low-potential-value customers) to close their accounts with the bank. This policy helps to minimize future financial losses to the bank, improving overall profitability and also making sure that the bank’s most valuable customers (MVCs) are not subsidizing its lowest-value customers, which is more trustworthy behavior than expecting good customers to pay more than they might to cover the losses caused by bad customers.

Assessing customer value as a combination of current and potential value is no longer a choice if a firm wants to remain truly competitive. Estimating a customer’s potential value is certainly more complex than simply trying to forecast actual value, or LTV, and requires a deeper look into factors such as needs, lifestyle phases, and behavioral trends. But making a genuine attempt to do so will likely prove quite beneficial.10

Growing Share of Customer

With respect to its relationship with a customer, the goal of any customer-strategy enterprise should be to positively alter the customer’s financial trajectory, increasing the customer’s overall value to the enterprise. The challenge, however, is to know how much the enterprise really can alter that trajectory—how much increase in the customer’s value an enterprise can actually generate. (A new baby will go through 7,000 diapers between birth and toilet training. If your company sells disposable diapers, your goal will, of course, be to get as many of the diapers used to be your brand. But there’s likely not anything you can do to get Mom and Dad to have a second infant!)

Unrealized potential value is a term used to denote the amount by which the enterprise could increase the value of a particular customer if it applied a strategy for doing so. It’s a very straightforward concept, really, because the unrealized potential of a customer is simply the difference between the customer’s potential value and actual value. It represents the potential additional business a customer is capable of doing with the enterprise, much of which may never materialize. As an enterprise realizes more and more of a customer’s potential value, however, it can be said to have a greater and greater share of that customer’s business. (Indeed, if we divide a customer’s actual value by the customer’s potential value, the quotient should give us “share of customer.”)

Increasing share of customer11 is an important goal for a customer-strategy enterprise and can be accomplished by increasing the amount of business a customer does, over and above what was otherwise expected (i.e., by applying a strategy to favorably affect the customer’s trajectory). This is often referred to as “share of wallet.” For example, a bank might have a relationship with a customer who has a checking account, an auto loan, and a certificate of deposit. The customer provides a regular profit to the bank each month, generated by transaction fees and the investment spread between the bank’s own investment and borrowing rates, compared to the lending and savings rates it offers the customer. The net present value of this income stream over the customer’s likely future tenure is the customer’s LTV. This LTV amount is equivalent to the present value of the financial benefits the bank would lose in the future, if the customer were to defect to another financial services organization today.

But suppose that, in addition to the accounts the customer now maintains at the bank, he also has a home mortgage at a competitive institution. This loan represents unrealized potential value for the bank, while it represents actual value to the bank’s competitor. The expected profit from that loan is one aspect of the customer’s potential value to the bank, which may devise a strategy to win the customer’s mortgage loan business away from its competitor.

Or suppose this customer owns a home computer and modem but doesn’t participate in the bank’s online banking service. If he were to do more of his banking online, however, the cost of handling his transactions would decline, his likelihood of defection would decline, and his value to the bank would increase. Thus, the increased profit the bank could realize if the customer banked online represents another aspect of the customer’s potential value to the bank.

Or perhaps the customer is a night student attempting to qualify for a more financially rewarding career. If the bank could help him achieve this objective, he would earn more money and do more banking, and his value to the bank would increase. All these possibilities represent real opportunities for a bank to capture some of a customer’s unrealized potential value.

Different Customers Have Different Values

Increasing a customer’s value encompasses the central mission of an enterprise: to get, keep, and grow its customers. When it understands the value of individual customers relative to other customers, an enterprise can allocate its resources more effectively, because it is quite likely that a small proportion of its most valuable customers will account for a large proportion of the enterprise’s profitability. This is an important principle of customer differentiation, and at its core is what is known as the Pareto principle, which asserts that 80 percent of any enterprise’s business comes from just 20 percent of its customers.12 The Pareto principle implies that an Internet retailer ranking its customers into deciles by value is likely to find that the top two deciles of customers account for 80 percent of the business the company is doing. Obviously, the percentages can vary widely among different businesses, and one company might find that the top 20 percent of its customers do 95 percent of its business while another company finds that the top 20 percent of its customers do only 40 percent of its business. But in virtually every business, some customers are worth more than others. When the distribution of customer values is highly concentrated within just a small portion of the customer base, we say that the value skew of the customer base is steep.

While LTV is the variable an enterprise wants to know, often a financial or statistical model is too difficult or costly to create. Instead, the enterprise may find some proxy variable to be nearly as useful. A proxy variable is a number, other than LTV, that can be used to rank customers in rough order of LTV, or as close to that order as possible, given the information and analytics available. A proxy variable should be easy to measure, but it obviously will not provide the same degree of accuracy when it comes to quantifying a customer’s actual value or ranking customers relative to each other.

For instance, many direct marketers use a proxy variable called RFM, for recency, frequency, and monetary value, to rank-order their customers in terms of their value. The RFM model is based on individual customer purchase histories and incorporates three separate but quantified components:

- Recency. Date of this customer’s most recent transaction.

- Frequency. How often this customer has bought in the past.

- Monetary value. How much this customer has spent in the most recent specified period.

An airline, by contrast, might use a customer’s frequent-flyer mileage as a proxy variable to differentiate one customer’s value from another’s. The mileage total for the past year, or the past two years, or some other period, will be a good indicator of the customer’s value, but it won’t be entirely accurate. For instance, it won’t tell the airline whether the customer usually flies in first class or in coach, and it won’t tell whether the customer always purchases the least expensive seat, frequently chooses to stay over on Saturdays, and takes advantage of various other pricing complexities and loopholes in order to guarantee always obtaining the lowest fare. And, as we noted before, it doesn’t reveal anything about potential value based on share of customer.

A proxy variable is, in effect, a representation of a customer’s value to the enterprise rather than a quantification of it. Nevertheless, proxy variables can be efficient tools for helping an enterprise rank its customers based on value, and with this ranking the company still can apply different strategies to different customers, based on their relative worth. Although more feasible all the time, sophisticated LTV models can be expensive and time consuming to create. If an enterprise is to explore and benefit from customer valuation principles, proxy variables that allow initial rank-ordering of customers by value are a good starting point.

The goal of value differentiation is not a historical understanding but a predictive plan of action. RFM and other, similar, proxy-variable methods show that while differentiating among customers can be mathematically complex, it is still fundamentally a simple principle.

Customer Value Categories

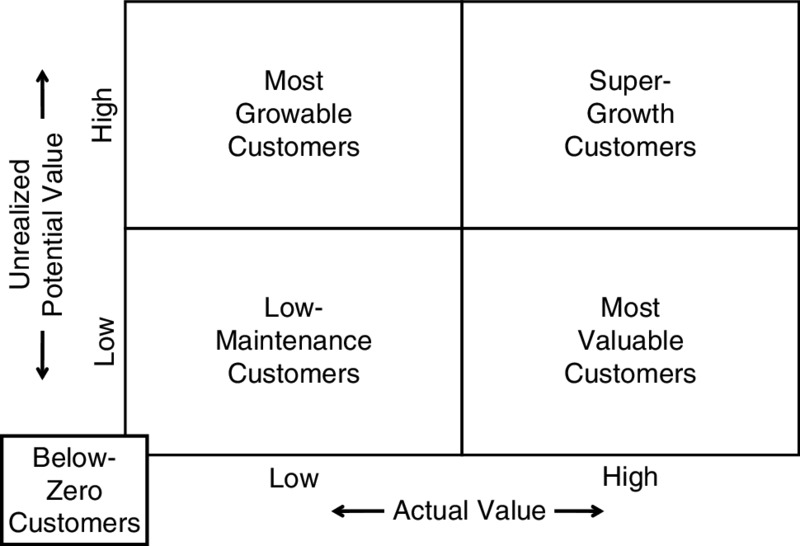

Every customer has an actual value and a potential value. By visualizing the customer base in terms of how customers are distributed across actual and potential values, marketing managers can categorize customers into different value profiles, based on the type of financial goal the enterprise wants to achieve with each customer. For instance, one of a company’s goals for a customer with a high unrealized potential value would be to grow its share of customer (in order to realize some of this value), while one of the goals for a customer with low actual value and low potential value would be to minimize servicing costs. By thinking of individual customers in terms of both each one’s actual value (i.e., current LTV) and its unrealized potential values (i.e., growth potential), a company could array its customers roughly as shown in Exhibit 5.3. (We will talk more about managing experiences and values for these customers in Chapter 14.)

Exhibit 5.3 Customer Value Matrix

Five different categories of customers are shown on this diagram, and an enterprise should have different strategic goals for each one:

- Most valuable customers (MVCs). In the lower right quadrant of Exhibit 5.3, MVCs are the customers who have the highest actual value to the enterprise. This could be for any or all of a number of different reasons: they do the highest volume of business, yield the highest margins, stay more loyal, cost less to serve, and/or have the highest referral value. MVCs are also customers with whom the company probably has the greatest share of customer. These may or may not be the traditional “heavy users” of a product; the MVC may, for example, fly a lot less often but always pays full fare for first-class tickets. The primary financial objective an enterprise will have for its MVCs is retention, because these are the customers likely giving the company the bulk of its profitability to begin with. In the airline business, these are the “platinum flyers” in the frequent-flyer program. In order to retain these customers’ patronage, an airline will give out bonus miles, offer special check-in lines, provide club benefits, and so forth. For a pharmaceutical company marketing prescription drugs to physicians, however, the most valuable customers may be those particular physicians who have the most influence over other physicians. (See “Customer Referral Value.”)

- Most growable customers (MGCs). In the upper left quadrant of Exhibit 5.3, MGCs are customers who have little actual value to the enterprise today but significant growth potential. Here, of course, the enterprise’s financial objective is to realize some of that potential value. As a practical matter, these customers are often large-volume or high-profit customers who simply patronize a different company. MGCs are often, in fact, the MVCs of the enterprise’s competitors. So the company’s objective will be to change the dynamics in some way so as to achieve a higher share of each of these customers’ business. (Don’t forget, however, that the reverse is also true: Your own MVCs are your competitors’ MGCs.)

- Low-maintenance customers. In the lower left quadrant are customers who have little current value to the enterprise and little growth potential. But they are still worth something (i.e., they are still profitable, at some level), and there may indeed be a whole lot of them. The enterprise’s financial objective for low-maintenance customers should be to streamline the services provided to them and to drive more and more interactions into more cost-efficient, automated channels. For a retail bank, for instance, these are the vast bulk of middle-market customers whose value will increase substantially if they can be convinced to use the bank’s online services rather than taking the time and attention of tellers at the branch.

- Super-growth customers. In the upper right quadrant of Exhibit 5.3, many enterprises will have just a few customers who have substantial actual value and also a significant amount of untapped growth potential. This is more likely to be true for B2B firms than for consumer-marketing companies. If a company sells to corporate customers, it will likely have a few very large firms in its customer base that are giant, immense firms that already give the company a substantial amount of business. That is, they are likely already high-value customers, but they are so immense that they could still give the enterprise much more business. No matter what size B2B firm an enterprise is, if it sells to Microsoft, or Intel, or Toyota, or GE, or other corporate customers with similarly large financial profiles, chances are these customers are super-growth customers. The business objective here is not just to retain the business already achieved but to mine the account for more. There is one caveat, however: Sometimes super-growth customers, who obviously know that they represent immense opportunity for the companies they buy from, use their customer relationships to drive very hard bargains, squeezing margins down as they push volumes up. They can be merciless, because they know they are highly valuable to the firms they choose to buy from. (See “Dealing with Tough Customers.”)

- Below zeros (BZs). With very low or negative actual and potential values, BZs are customers who, no matter what effort a company makes, are still likely to generate less revenue than they cost to serve. No matter what the firm does, no matter what strategy it follows, a BZ customer is highly unlikely ever to show a positive net value to the enterprise. Nearly every company has at least a few of these customers. For a telecommunications company, a BZ might be a customer who moves often and leaves the last month or two unpaid at each address. For a retail bank, a BZ might be a customer who has little on deposit with the bank, but tends to use the teller window often. (Some banks in the United States estimate that as many as 40 to 50 percent of their retail customers are, in fact, BZs.) For a B2B firm, there can be a razor-thin difference between a super-growth customer and a BZ, because some giant business clients can threaten to drive margins down so low that they no longer cover the cost of servicing the account. The enterprise’s strategy for a BZ should be to create incentives either to convert the customer’s trajectory into a breakeven or profitable one (e.g., by imposing service charges for services previously given away for free) or to encourage the BZ—very politely—to become someone else’s unprofitable customer.

This categorization of customers by their value profiles is fairly arbitrary, because it presumes customers can be split into just a few tight groups, based on actual and potential value. But whether the enterprise uses the MVC-MGC-BZ typology or not, what should be clear is that the enterprise should have different financial objectives for, and invest different resources in, different customers, based on its assessment of the kind of value each customer is or is not creating for it already and what kind of value is possible.

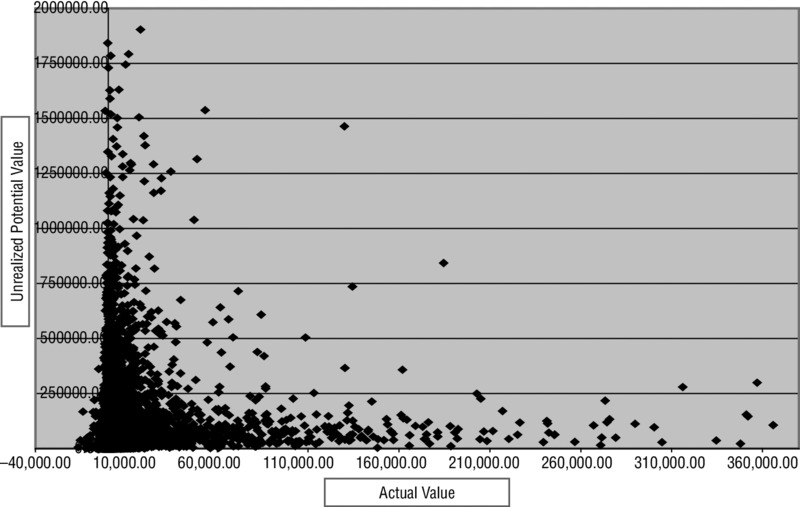

One large B2B company performed a value analysis of its customer base and arrayed its customers by actual value and unrealized potential value, creating the scattergram shown in Exhibit 5.5. Each of the dots in the exhibit represents a different business customer. The customers in this graph who occupy the long spike out to the right represent this company’s MVCs. Clearly, these are the customers giving the company the most business, and few of them have much unrealized potential value, because the company is getting the bulk of each one’s patronage in its category. Down in the lower left of the graph we can find a few customers who have less than zero actual value; these (of course) are this company’s BZ customers.

Exhibit 5.5 National Accounts’ Actual versus Unrealized Potential Value

The tall spike up the left-hand side of the scattergram represents this company’s MGCs. These are the customers who don’t give the firm much of their business right now but clearly have a great deal of business to give it, if they could be convinced to do so. You might note that the horizontal-vertical scales on this scattergram are not the same—that is, the vertical spike, if drawn to the same scale as the horizontal one, would soar up the page much farther than the illustration allows. And most of the customers in this vertical spike are the company’s competitor’s MVCs.

Managing the Mix of Customers

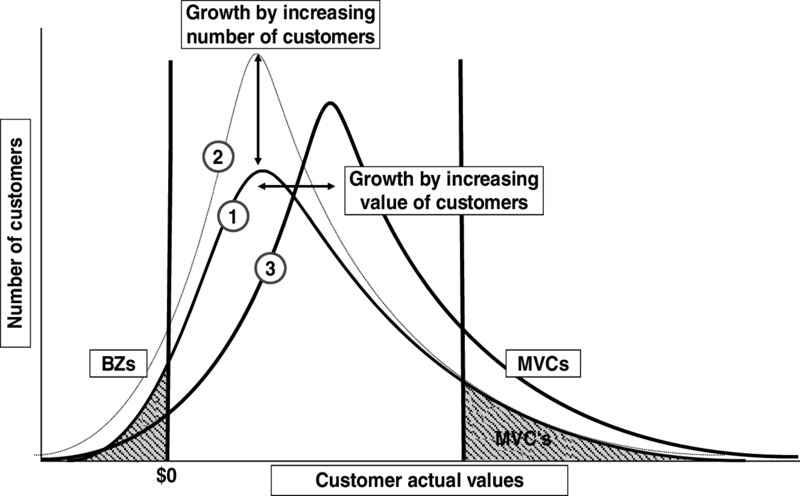

One way to think about the process of managing customer relationships is that the enterprise is attempting to improve its situation not just by adding as many new customers as possible to the customer base but also by managing the mix of customers it deals with. It wants to add to the number of MVCs, create more profitability from its MGCs, and minimize its BZs. An enterprise in this situation could choose either to emphasize adding new customers to its customer base or (instead or in addition) to increase the values of the customers in its customer base. So imagine if an enterprise were to plot the distribution of its customer values on a chart, as in Exhibit 5.6, with actual values of customers shown across the bottom axis and the number of customers shown up the vertical axis.

Exhibit 5.6 Managing the Mix of Customers

Curve 1 on Exhibit 5.6 shows the enterprise’s current mix of customers, with just a few BZs and MVCs and the bulk of customers lying in between these two extremes. By applying a customer-acquisition marketing strategy the enterprise will end up acquiring more and more customers, but these customers are likely to show the same mix of valuations as in its current customer base, as shown by Curve 2. Market share will likely improve, but the mix of customers will almost certainly remain the same. In fact, a customer acquisition strategy often results in a degraded mix of customer values, when an enterprise focuses on the number of customers acquired (as happens at many companies) without respect to their values. Almost by definition, low-value customers are easier to acquire than high-value customers. If the only variable being measured by the firm’s management is the number of customers acquired, then average customer values will almost certainly decline rather than remain the same.

If, however, the enterprise employs a customer-centric strategy, it will not be trying to acquire just any customers; instead, it will be focusing its customer acquisition efforts on acquiring higher-value customers. Moreover, it will focus a lot of its effort on improving the value of its existing customers, and moving them up in value individually. The result of such a strategy is shown as Curve 3 in Exhibit 5.6. An enterprise that launches a successful CRM effort will end up shifting the customer mix itself, moving the entire customer base into a higher set of values.

Creating a valuable customer base requires understanding the distribution of customer relationship values and investing in acquisition, development, and retention accordingly.13 Think of this as customer value management. By taking the time to understand the value profile of a customer relative to other customers, enterprises can begin to allocate resources intentionally to ensure that the most valuable customers remain loyal. The future of an enterprise, therefore, depends on how effectively it acquires profitable new customers, develops the profitability of existing customers, and retains existing profitable relationships.14 Customers will want to spend money with a business that serves them well, and that is nearly always a company that knows them well and uses that knowledge to build relationships in which customers perceive great value and benefit.15

Certainly one of the most important benefits of ranking customers by value is that the enterprise can more rationally allocate its resources and marketing efforts, focusing more on high-value and high-growth customers and less on low-value customers. Moreover, the enterprise will likely find it less attractive, as a marketing tactic, to acquire strangers as “customers”—some of whom will never be worth anything to the company.

Janet LeBlanc, named a 1to1 Customer Champion by 1to1 Media, tells the story about how Canada Post differentiated its customers by value and, in the process, increased top-line revenue and cut costs to serve as well.

Summary

For an enterprise to engage its customers in relationships, it must be prepared to treat different customers differently. Before designing its relationship-building strategy, the firm must understand the nature of its customers’ differences, one from another. From Chapter 5, we know that the value of a customer is a function of the future business the customer does with the enterprise, and that different customers have different values. Knowing which customers are more valuable allows an enterprise to allocate its relationship-building efforts to concentrate first on those customers who will yield the best financial return. However, because the future patronage of any customer is not something that can actually be known in the present, making decisions with respect to customer valuation necessarily involves approximation and subjectivity. Companies with large numbers of customers whose transactions are electronically tracked in a detailed way might be able to use advanced statistical modeling techniques to make reasonably accurate forecasts of the future business that particular types of customers will likely do with the firm, but for the vast majority of enterprises, no such scientific models may be readily available. Instead, companies that rank their customers by value usually do so by using a mix of judgment and proxy variables—at least at first.

As this chapter has shown, the enterprise that defines, quantifies, and ranks the value of its individual customers takes great strides toward becoming a business truly based on growing customer value. By relying on a taxonomy of customer types based on their value profile—including not just actual values but unrealized potential values as well—the enterprise can create a useful model for how it would like to alter the trajectories of individual customers. Not only can it devote a greater portion of its internal resources to serving its most valuable customers, but it also can set more rational financial objectives for each customer, based on that customer’s value profile.

Setting financial objectives is only a part of the job, however. To achieve those objectives for each customer, no matter what they are, the enterprise will have to alter the customer’s trajectory. It will have to help change the customer’s behavior in a way that benefits the customer; that is, it will need to get a customer to do something (or not do something) that he or she was not otherwise going to do. To do this in the most efficient way possible, the enterprise needs to be able to appeal directly to the customer’s motivations. It must communicate to the customer in a way that the customer is going to understand. It must, in a word, understand the customer’s own perspective and needs.

In Chapter 6, we will explore how the enterprise can differentiate its customers based not just on their value profiles, but on their individual needs as well.

Food for Thought

- Why is it not enough to consider average customer value?

- How often should actual value be calculated? Potential value? Why?

- Search the Web for a company that has successfully “fired” customers in the past. If you were facing a detractor—someone who said that it’s wrong to treat different customers differently—how would you defend “firing” customers in this reported or even a hypothetical instance?

- What policies are successful, and what policies are likely to create mistrust? What are likely to be the best measures of actual and potential value for each of the listed customer bases? How would you confirm that your answer is right? Would the company likely be best served by proxy or statistical/financial value analysis?

- Customers for a B2B electronics components distributor

- Customers for a dry cleaner

- Customers for an automobile manufacturer; for an automobile dealer

- Customers for a chemical supply company

- Customers for a discount department store

- Customers for a large regional supermarket chain

- Customers for a long-haul trucking company

- Customers for Disney World; for Six Flags; for Club Med

- Customers for CNN; for HBO (Caution: They’re different. CNN sells viewers to advertisers while HBO sells programming to viewers.)

- “Customers” for a political campaign; for the American Cancer Society; for NPR (formerly National Public Radio); for Habitat for Humanity

- For each of the companies listed in number 4, what’s the next step? How does a company use the information about customer value to make managerial decisions?

Glossary

- Actual value

-

The net present value of the future financial contributions attributable to a customer, behaving as we expect her to behave—knowing what we know now, and with no different actions on our part.

- Below zero (BZ)

- The below-zero customer will, no matter what strategy or effort is applied toward him, always cost the company and its best customers more than he contributes.

- Customer focus

- An attitude or mind-set that attempts to take the customer’s perspective when making business decisions or implementing policies. Also called customer orientation.

- Customer service

- Customer service involves helping a customer gain the full use and advantage of whatever product or service was bought. When something goes wrong with a product, or when a customer has some kind of problem with it, the process of helping the customer overcome this problem is often referred to as “customer care.”

- Customer-strategy enterprise

- An organization that builds its business model around increasing the value of the customer base. This term applies to companies that may be product oriented, operations focused, or customer intimate.

- Customer value management

- Managing a business’s strategies and tactics (including sales, marketing, production, and distribution) in a manner designed to increase the value of its customer base.

- Customize

- Become relevant by doing something for a customer that no competition can do that doesn’t have all the information about that customer that you do.

- Differentiate

- Prioritize by value; understand different needs. Identify, recognize, link, remember.

- Disruptive innovation

- Innovation likely to upset an established business model that governs how a number of competitors operate. Uber, for instance, is an innovation that disrupts how most established taxi and limousine services operate.

- Enterprise resource planning (ERP)

- The automation of a company’s back-office management.

- Identify

- Recognize and remember each customer regardless of the channel by or geographic area in which the customer leaves information about himself. Be able to link information about each customer to generate a complete picture of each customer.

- Lifetime value (LTV)

- Synonymous with “actual value.” The net present value of the future financial contributions attributable to a customer, behaving as we expect her to behave—knowing what we know now, and with no different actions on our part.

- Low-maintenance customers

- Customers with low actual values and low unrealized potential values. They are not very profitable for the enterprise individually, nor do they have much growth potential individually. But there are probably a lot of them.

- Mix of customer values

- For a particular company, the mix refers to the percentage of most valuable customers versus most growable customers versus below-zero customers.

- Most growable customers (MGCs)

- Customers with high unrealized potential values. These are the customers who have the most growth potential: growth that can be realized through cross-selling, through keeping customers for a longer period, or perhaps by changing their behavior and getting them to operate in a way that costs the enterprise less money.

- Most valuable customers (MVCs)

- Customers with high actual values but not a lot of unrealized growth potential. These are the customers who do the most business, yield the highest margins, are most willing to collaborate, and tend to be the most loyal.

- NPV

- Net present value.

- Net Promoter Score (NPS)

- A compact metric owned by Satmetrix and designed initially by Bain’s Fred Reichheld to quantify the strength of a company’s word-of-mouth reputation among existing customers, and widely used as a proxy for customer satisfaction. See www.satmetrix.com.

- Potential value

- The net present value of the future financial contributions that could be attributed to a customer, if through conscious action we succeed in changing the customer’s behavior.

- Predictive analytics

- A wide class of statistical analysis tools designed to help businesses sift through customer records and other data in order to model the likely future behaviors of other, similar customers.

- Share of customer

- For a customer-focused enterprise, share of customer is a conceptual metric designed to show what proportion of a customer’s overall need is being met by the enterprise. It is not the same as “share of wallet,” which refers to the specific share of a customer’s spending in a particular product or service category. If, for instance, a family owns two cars, and one of them is your car company’s brand, then you have a 50 percent share of wallet with this customer, in the car category. But by offering maintenance and repairs, insurance, financing, and perhaps even driver training or trip planning, you can substantially increase your “share of customer.”

- Super-growth customers

- Customers with high actual value and high unrealized potential value as well.

- Switching cost

- The cost, in time, effort, emotion, or money, to a business customer or end-user consumer of switching to a firm’s competitor.

- Trajectory

- The path of the customer’s financial relationship through time with the enterprise.

- Unrealized potential value

- The difference between a customer’s potential value and a customer’s actual value (i.e., the customer’s lifetime value).

- Value skew

- The distribution of lifetime values by customer ranges from high to low. For some companies, this distribution shows that it takes a fairly large percentage of customers to account for the bulk of the company’s total worth. Such a company would have a shallow value skew. Another company, at which a tiny percentage of customers’ accounts for a very large part of the company’s total value, can be described as having a steep value skew.

- Word of mouth (WOM)

- A customer’s willingness to refer a product or service to others. This referral value may be as small as an oral mention to one friend, or a robust announcement on social media, or may be as powerful as going “viral.”