Chapter 12. Content modeling: Adaptive content design

Models formalize the structure of your content in guidelines, templates, and structured frameworks. When you model your content, you identify and document the structure on which your unified content strategy is based.

To ensure that content is reusable and adaptable, it must follow a consistent approach in writing style and structure. In addition, content must be stored in such a way that whoever needs the content can find it, access it, reuse or repurpose it, and deliver it (often dynamically) when and where it’s needed.

This chapter discusses the basics of content modeling and adaptive content. We describe granularity, information product and component models, and semantic structure.

What is adaptive content?

Adaptive content is format-free, device-independent, scalable, and filterable content that is transformable for display in different environments and on different devices in an automated or dynamic fashion.

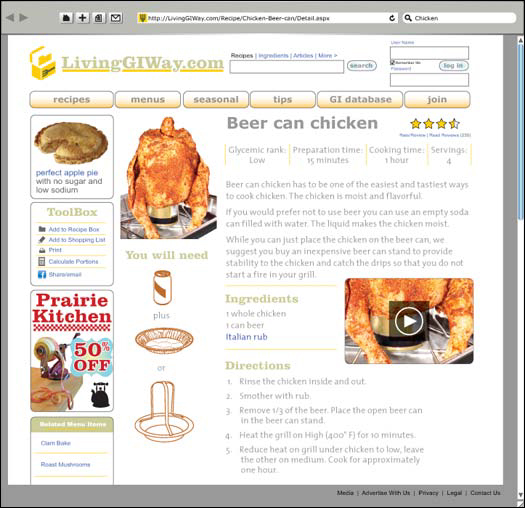

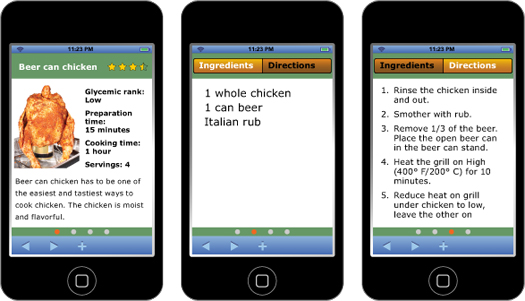

Customers want to access content on the device of their choosing. For example, because they were designed with 13-inch, 15-inch, and 17-inch screens in mind, traditional websites don’t display well on mobile devices with small screens. Customers who attempt to access sites that are not optimized for mobile use experience frustration when they try to click on miniscule links or use an interface that was not designed for their device. Developers have done a brisk business developing mobile versions of websites for multiple devices (iPhone, iPad, Black-Berry, and so on). But handcrafting mobile versions for every new device is unsustainable, particularly given the explosion of new devices hitting the market every year. It is not necessary or practical to create countless custom-designed solutions for every new device.

Ethan Marcotte coined the term “responsive web design” and transformed the way websites are visually designed. Responsive web design uses a variety of software techniques to respond to the environment based on screen size, platform, and orientation. This means that content designed for desktop web is automatically resized to the screen size of the device in use.

However, while changing how content is visually displayed is a good start, it’s not enough. Customers need adaptive content—content that will scale and adapt to the environment and their purpose.

Adaptive content automatically adjusts to different environments and device capabilities to deliver the best possible customer experience, filtering and layering content for greater or lesser depth of detail. Adaptive content can be displayed in any desired order, made to respond to specific customer interactions, changed based on location, and integrated with content from other sources. Adaptive content is limited only by your design decisions, the functionality of the device being used, and the intelligence of your content.

Content models make it possible to support adaptive content.

Understanding content modeling

Bear with us as we define a number of terms you need to understand for content modeling.

Content modeling is the process of determining the structure and granularity of your content.

Content models define the structure of information products and their constituent content components.

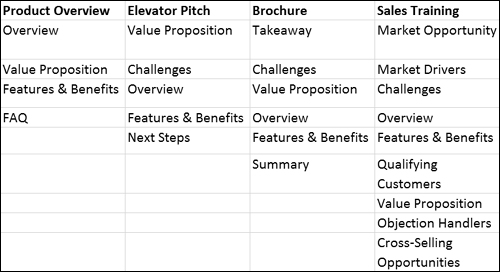

An information product is an assembly of content components, for example, a press release, an executive profile, a brochure, or an instructional course.

An information product model (IPM) is a hierarchical ordering of components. The IPM can be used over and over again with slight variations for different content.

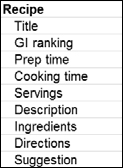

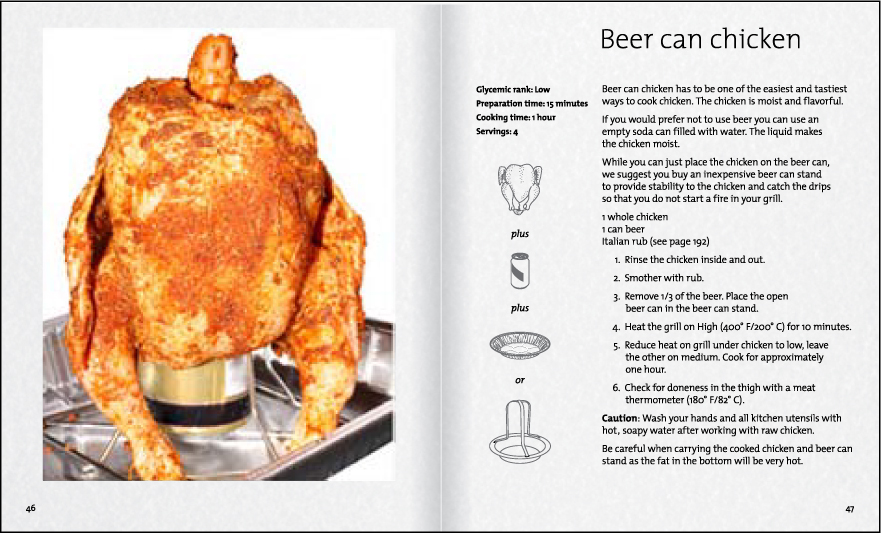

Components are the building blocks of your content. A component model describes the structure of specific types of content, for example, recipe, value proposition, or overview. Component models can be used over and over again with different content. Components can be reused in different information product models. The structure remains the same; only the content changes. Components break down further into elements.

An element is the smallest part of a component that can be semantically defined but not broken out into a separate component.

Content modeling takes place after you’ve completed your analysis and you know who your customers are, what they need, and what form they need it in.

Content modeling is critical in a unified content strategy because it provides the blueprint on which your content will be built. Content models define the structure of your content.

The content modeling process forces you to consider all content requirements, either for a specific information product, product or service, a specific customer, or a specific device, and to assess what content should be available to fulfill those requirements. And it forces you to design content for a usage you may not have even thought of yet! In a unified content strategy, the content model becomes the catalog of your content.

Content first, not mobile first, eBook first, or any other “first”

As each new device comes out, organizations realize that it’s going to be a very painful and time-consuming experience to get their content from its current format to a format that’s not only supported by the device, but also actually optimizes the content on the device for the best possible user experience. When intelligence is added to the content, it can be responsive to the people or device. When rules are added to the content, it can adapt to the customer’s actions.

When the Web became popular, it quickly became obvious that standard, print-based content wasn’t suited for the Web. It was too verbose, formatted for paper presentation, poorly structured for the screen, and designed to be read linearly. Huge numbers of articles, blogs, and books guided authors in writing for the Web. All good things, but all limited to changing the way authors write to optimize their content solely on the Web.

Now that content is increasingly needed in mobile formats, organizations are finding their websites don’t work well on mobile devices. Screen size is much smaller, and design-intensive websites are nearly impossible to navigate. Limited bandwidth and costly data plans can limit what you deliver.

Traditional publishers are scrambling to rapidly convert their print books (back catalog) to eBooks. The results are often lacking in quality and sometimes difficult to read. The more complex the content, the harder it is to successfully move it to eBook formats. For example, textbooks typically feature an intensive use of formatting and layout techniques to communicate lessons to students. These learning experiences are difficult to convert to eBooks. You can’t just use “file save as” PDF or EPUB and expect it to work without incident. These books contain too many handcrafted layout structures like sidebars, two-page spreads, tables, and columns that sabotage any simple conversion.

Content strategists cannot, and we repeat, cannot, continue to handcraft content for a particular output. If you want your content to be adaptive, you can’t think about how it will look and then tweak and tune the content to get that perfect fit. You can’t design your content strategy around a particular page or layout. You have to create a content strategy that’s only about the content and its purpose, scope, use, and reuse. You need to know what content is required, by whom, when, in what circumstance, and in conjunction with what other content or interactivity.

The only way you’ll achieve your goals is with structured models and intelligent content.

Know your constraints

Even though you should write content separate from its eventual output, you must understand the constraints of the device on which your content will be displayed. Then you need to design your models to adapt to those constraints.

The constraints of print and the Web are pretty well known at this point, so we’ll just focus on some of the new devices. Note that devices are changing rapidly, so the constraints at the time of writing may be different than when you read this book.

Constraints of mobile

The constraints of mobile include:

• Small screen size

Customers don’t want to have to constantly be scrolling, swiping, or pinching to view content. It’s time-consuming and tiring, and it suddenly makes reading a two-handed operation. Create models and associated guidelines that accommodate “bite-sized” pieces of content.

Put the key information in the first paragraph or sentence of any element of content so that the rest can be filtered out or made accessible with functionality such as Read more. Think of the first paragraph or sentence as a building block. Then each subsequent paragraph can build on the previous one.

Explore the practical use of images, graphics, and rich media to communicate ideas that don’t require words.

• File size

Customers don’t want to wait for content to arrive. They want it now. Large file sizes take a long time to deliver, and that’s frustrating—whether it’s a web page with animations, high fidelity audio or video files, or a document server delivering content (such as an eBook) designed to be read offline at a later date. Waiting for a large chunk of content to arrive can be irritating.

Break apart your content and deliver it in smaller chunks. If you’re delivering content for offline reading and it must be sent in one piece, consider creating a version for mobile—one that relies less on audio, video, and other rich media and will therefore be smaller to deliver. Design your content to quickly convey information even in a restricted delivery mode.

If you need to deliver to a mobile device, plan for mobile delivery when you are designing your content. Ask yourself, for a given topic or page of content, if I can only deliver text, what text-based content is needed? Then determine what rich media could be added that would enhance the user experience. Deliver the rich media to the devices or environments that can handle or support it.

Large files can be expensive, not for the publisher or deliverer, but for the customer. If your customers use a cellular connection and they’re out of their home area, roaming charges can be a significant barrier. Deliver content optimized for mobile. This will help prevent an excessive expense to customers.

• Download or connection speed

The differences in speed between older model smartphones and newer models can be quite significant.

Small file sizes are key. Also, depending on the technology used, it’s sometimes possible to restrict the use of an application or the downloading of large files based on the connection method or the connection speed.

• Device performance

Due to memory limitations or processor speed, content may download quickly but take a long time to render on the screen. Once again, it’s often possible for the system to determine the device capabilities and provide the content you have defined as being appropriate to the device.

Constraints of eBooks

eBooks involve a number of constraints, and ironically eBooks are more constrained on eReaders (specific eBook devices) than they are in eReader software (software that runs on your desktop, tablet, or smartphone). eBooks aren’t good at:

• Complex tables (greater than four or five columns and rows)

• Images:

• Images with captions and callouts

• Multiple images related to a single callout

• Large, complex images, especially those spanning most of a page or across pages

• Images not referenced from the text

• Images embedded in text

• Images that are pretty but serve no specific purpose (for example, images at the beginning of a chapter)

• Columns

• Sidebars

• Margin notes

• Margin icons

• Icons associated with text

• Use of shading or color to highlight information

• Text that wraps around images

• Equations and math symbols

• Long, dense paragraphs

eBooks really exemplify the need to separate content from format. An eBook is not a print book. If you’re publishing to both print and eBooks, structured components are critical so you can define how the content will be handled in a given situation. For example, sidebars should be placed after the content they’re logically related to.

More information on designing for eBooks can be found in eBooks 101: The Digital Content Strategy for Reaching Customers Anywhere, Anytime, on Any Device by Ann Rockley and Charles Cooper.

Creating models

There are two levels of content modeling required: modeling at the information product level and modeling at the component level.

Information product models

When you model an information product (such as a press release, an instructor guide, a website, or a brochure), you determine the structure of the product. The structure is a hierarchy or collection of content components. Later, in component modeling, you will determine the structure of those individual components.

Authors follow the model to create and compile information products consistently. If you automate content assembly, the system uses the models to determine what content is valid in what context.

Component models

In addition to product models, you need to create component models. A component model breaks down the information product model even further. It describes the element structure of the components that are assembled to create the information product.

Understanding granularity

A content model reflects all the components that make up each information product; the level of detail in the model depends on the granularity. Granularity determines the smallest piece of information that’s defined by your structure.

There are two types of granularity:

• The granularity of reuse (components)

• The granularity of structure

Granularity of reuse

The granularity of reuse identifies the size of your components. Components can be reused in multiple information products. Having content chunked into components makes it easy to select a component for reuse.

A number of components are reused across the information products, including the following:

• Overview

• Challenges

• Features & Benefits

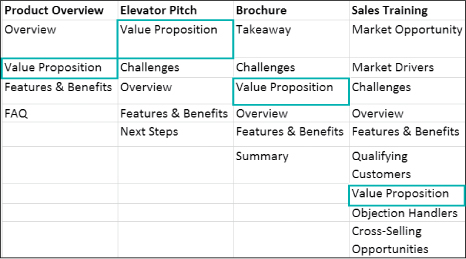

• Value Proposition

• Content is a logically self-contained chunk of information.

• Content can be reused across and within information products.

The granularity of structure

The granularity of structure defines the semantic structure within a component. The semantic structure guides authors so that they can see exactly what to include as they write. The semantic structure can also be filtered and acted on using system rules. When we looked at the value proposition, we could have chosen to have a component (for example, no semantic element structure) called Value Proposition. Certainly an author understands what a value proposition is, and in many cases could write a pretty good value proposition, but there would always be variations in the way the value propositions of your organization get written. A more granular semantic structure, as shown in Figure 12.2, can be used in a number of ways:

• The elements of the Value Proposition component can clearly guide authors in writing consistent and effective value propositions.

• If the Cost of Offering is a complex table, it could be excluded from mobile.

• If the Value Proposition is written clearly and succinctly and is restricted to 140 characters, this element could be automatically delivered through Twitter.

You don’t need to chunk content out into its component parts to gain the value of reuse and automated delivery. The semantic structure of the elements is accessible to the software that manages the content.

Although granularity must be reflected in the content model, the level of granularity can change throughout your content. In one instance you may decide to define a very detailed semantic structure; in others, you may decide to break content out into its component parts.

However, care should be exercised when determining the level of granularity. The more granular the content, the greater the complexity of modeling, authoring, and managing the content. Yet if the content isn’t granular enough, you compromise your ability to support adaptive content and lose the authoring guidance that detailed structure provides.

Weigh the benefits and reasons for very granular content before modeling and implementing it. You also need to consider that the meaning of an element may change if it’s used out of context. If an element relies on surrounding information to make its meaning clear, the surrounding information may need to be included as part of the element. At first, you may find it necessary to model very granular information. Then, before you implement it, you will need to review the model in the context of how information will actually be authored, reused, and manipulated. Note, for example, that we don’t typically recommend granularity at the word level. It’s extremely difficult to model and maintain, and can impede the writing and maintenance process. In cases where you have word variations, you can use metadata to define variables that are inserted as required.

Keep in mind, too, that regardless of the level of granularity, authors still write coherent content, not elements. They may write full “documents,” sections, or other recognizable topics of information, but they don’t write separate sentences. Rather, authors write content, assigning the required granularity to elements (as defined by the content model) as they write. The granularity defines how the completed document is broken down, tagged, and stored for reuse. Refer to Chapter 13, “Reuse strategy” for more information on granularity.

How are models used?

Models support your content strategy in a number of ways. Models:

• Guide authors in content creation.

• Facilitate reuse.

• Support adaptive content.

Models support authors

Authors use content models to determine what information goes in which information product, as well as how to structure each component. For example, by referring to the content model, authors can determine that an information product requires an overview and what the structure of that overview should be. In addition, they can get hints or rules (guided authoring) about how to write certain components and their associated elements. You can provide detailed writing guidelines, and depending on your tools, embed the writing guidance in each element. For more information on structured writing guidelines refer to Chapter 16, “It’s all about the content.”

Models support manual reuse

Information product models identify the components that are required to create the information product. Authors write content to ensure that reusable content is appropriate wherever it appears. Reusable components can be opportunistically reused (authors specifically select components to reuse) or automatically reused (the system automatically populates the reusable content in the appropriate areas as defined by your reuse strategy).

Models support automatic reuse and adaptive content

Models provide the specification for the structure of your content. Adaptive content uses the structure to determine how to display, organize, and order content. Content strategists define the models and the rules for how content should be displayed in a given context.

How are models implemented?

Models become the specification for the structure of your content.

Information technologists use models to guide them in creating:

• Authoring templates

• XML document type definitions (DTDs) or schemas

• Forms

• Software structures that enforce the models

• Configuration plans for the content management system

• Delivery stylesheets

• Intelligent content to support adaptive delivery

Summary

Content modeling is the process of determining the structure and granularity of your content. Content models define the structure of information products and components.

Adaptive content automatically adjusts to different environments and device capabilities to deliver the best possible customer experience by filtering and layering content for greater or lesser depth of detail.

Content strategists can’t continue to handcraft content for a particular output. You can’t think about how content will look and tweak it until you get that perfect fit, and you can’t design your content strategy around a particular page or layout. You have to create a content strategy that’s all about the content, its purpose, scope, use, and reuse. You need to know what content is required, by whom, when, in what circumstance, and in conjunction with what other content or interactivity. And the only way you’ll achieve your goals is with structured models and intelligent content.

A content model reflects all the components that make up each information product; the level of detail in the model depends on the granularity. Granularity identifies the smallest piece of information that’s defined by your structure.

Models guide authors in content creation, facilitate reuse, and support adaptive content.