Chapter 15. Designing metadata

As you’ve no doubt noticed, more information is available than ever before—on the Web, on your company intranet, in your content management repository, and elsewhere. This is exciting and a problem, as well as extremely frustrating when you can’t find what you’re looking for.

What’s missing is information about the information—that is, labeling, cataloging, and descriptive information—that enables a computer to properly process and search the content components. This information about information is known as metadata.

Although metadata has been a buzzword in information technology and data warehousing, it has recently emerged as an important concept for those developing search and retrieval strategies in reference databases or on the Web, for authors of structured content, and for developers of enterprise content management and web publishing solutions. With more complex authoring processes and information delivery requirements, you need to classify and identify all the information or content “bits” so they can be retrieved and combined in meaningful ways. Well-designed metadata can provide the classification and identification you need.

This chapter introduces the levels and types of metadata that will be appropriate to your unified content strategy. It also describes methods for defining metadata.

What is metadata?

Traditionally, metadata has been defined as “data about data.” Although this is true, metadata is actually much more. Metadata is the encoded knowledge of your organization, described by David Marco as

all physical data (contained in software and other media) and knowledge (contained in employees and various media) from inside and outside an organization, including information about the physical data, technical and business processes, rules and constraints of the data, and structures of the data used by a corporation.1

This definition is significant because it includes the often-overlooked idea that metadata can be used to describe the data’s behavior, processes, rules, and structure. Describing information in this way is important when developing a sound metadata strategy for content search and retrieval, reuse, and dynamic content delivery, because you can determine not only what the content is, but also who uses it, how it will be used, how it will be delivered, and when.

Metadata is the glue that enables the system (and by extension, you) to find the information you need. It’s the “stuff” that allows computers to be “smart.” It’s the stuff that makes “intelligent content” intelligent. And when it’s missing or poorly implemented, it’s what makes us slap the side of the computer in frustration when we can’t find what we’re looking for.

Let’s take a look at the most common metadata that most people are familiar with, at least at a superficial level: the metadata used by Microsoft Office.

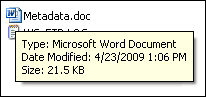

Open a Microsoft Word file and go to the Office Button > Prepare > Properties > Document Properties > Advanced screen. Click on the General tab and a box like the one shown in Figure 15.1 appears.

Figure 15.1. Metadata properties General tab.

It contains information about the file just opened, such as its name, when it was created, where it is located, and so on. Now, close the file and hover over the name in the File Manager (see Figure 15.2). Some of that same information (name, date modified, and size) will be displayed in the hover box.

Figure 15.2. Hover box showing metadata.

Right click on the filename and select Properties from the options presented. More information is displayed, such as where the file is located, when it was created (in addition to its last modification), and other details (see Figure 15.3).

Figure 15.3. Properties box from File Manager, showing metadata.

All this information is metadata, which allows you to know more about the file in question. On a Windows system, the metadata helps the search tool find particular files. This information is very generic though; by adding your own metadata to a file, it becomes more useful to you.

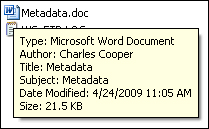

Reopen that Word file and once again navigate to the Properties dialog box. Select the Summary tab this time and you’ll see a window where you can enter your own information (see Figure 15.4).

Figure 15.4. Metadata properties, Summary tab.

Enter some information there (the Author, Subject, Keywords, and other information are entered in the example) and close the file. Once again, hover over the file name in Explorer to see a bit more information about what’s contained in the file—even without opening it (see Figure 15.5).

Figure 15.5. Hover box showing additional metadata.

In Microsoft Word, though, it’s the Custom tab that shows the power of metadata. In the Properties dialog box, select the Custom tab to open the scroll box containing a number of possible types of metadata, including Checked by, Department, Disposition, and so on (see Figure 15.6). Any of these can be selected and relevant information entered there. In content management, this is known as “tagging.”

Figure 15.6. Metadata properties, Custom tab.

The file can be tagged with the name of the reviewer (in this case, Joe Bloggs), the date the file was reviewed, and a host of other information. Any program that can read this information can use it to narrow searches and help find information. For example, if you’re looking for a particular file and you know that Joe Bloggs reviewed it, you can search for any Word file reviewed by Joe, and that’s all the search engine will look for.

The real strength of metadata is realized only when all the information available is tagged in a similar manner. If all members of an organization tag information in the same way, then they can build on that shared knowledge and find information across the organization with the help of the embedded metadata. Microsoft Word files, spreadsheets, images, movies, and more can be tagged for retrieval.

However, it’s when the contents of those files (the components that comprise them) are tagged that information can be found and reused throughout a department or organization. For example, content creators can now find individual components and reuse them rather than rewriting them.

Imagine a number of product lines for audio components in which all the brochures (across the product lines) are supposed to contain standard information about the company. If an audit were conducted, the findings would probably show that the “standard” content differs from brochure to brochure. And if each line is supposed to have a common description of the product, the findings would show that those “common” descriptions vary as well. However, if you were using a content management system to manage the content, you could identify that common company information with a tag, ensure that it’s “built into” all the documents, and ensure that the product-line-specific common descriptions are built into each of the product lines. And because of the tagging, the correct product line descriptions could be matched with the product lines. For example, the headphone descriptions would be built into the headphone materials, and the loudspeaker descriptions would be made available in the speaker materials—and not vice versa.

Benefits of metadata to a unified content strategy

In a unified content strategy, metadata enables content to be retrieved, tracked, and assembled automatically. Metadata enables:

• Effective retrieval

• Automatic reuse

• Automatic routing based on workflow status

• Tracking of status

• Reporting

Properly defining and categorizing the types of metadata you want to use is extremely important to the success of your unified content strategy. Improperly identified metadata, or missed categories, can cause problems ranging from mis-filed and therefore inaccessible content to more serious problems such as those encountered by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA’s) 1999 Mars Climate Orbiter mission, in which misidentified metadata resulted in the loss of the spacecraft, at a cost of $300 million!2

Using metadata for retrieval and content management results in the following benefits.

Reduction of redundant content

If content is consistently labeled with metadata, authors can easily retrieve existing reusable content, and if multiple authors accidentally create the same piece of content, your content management system identifies that multiple versions of the same content exist. With automatic reuse, the system assembles a document with the appropriate reusable content. If the content is already in place when authors start to write, they are aware that they do not need to create it again.

Improved workflow

When you tag content with metadata that identifies its status, workflow automatically manages that content. For example, a component marked with “Ready for review” can be compiled automatically into an information product such as a brochure, after which the brochure is automatically routed for review and approval.

Reduced costs

Metadata can reduce costs in a unified content strategy. For example, existing content identified with metadata can be easily retrieved and reused. The work required to create it again is eliminated. Metadata can also be used to automatically identify source components that have changed. Triggering a translation process for the component saves time otherwise spent identifying the content to be translated. Additionally, if a reusable component is already translated, the metadata can facilitate the automatic population everywhere the source component is reused to ensure that the component is not translated again.

Types of metadata

We’ve seen an example of entering metadata into Microsoft Word. You can imagine how this could enable customers to search for specific files. But to actually implement metadata in a consistent (and therefore useful) manner, you have to think about why you’re entering the it and how it will be used. You need to understand that there are different types of metadata for different purposes.

Unified content requires two types of metadata: descriptive and component. Customers tend to retrieve information based on descriptive metadata, whereas authors tend to retrieve information based on component metadata.

Descriptive or publication metadata is used to help customers find information—books in libraries, PDF files on a company fileserver, or content on the Web.

Component metadata is more granular. Although it can be used to find published information, its primary purpose is to give those creating content (or anyone involved in the content creation process, such as reviewers, editors, and subject matter experts [SMEs]) the ability to find information so it can be reused in different content assembly or for different purposes. We break down the component metadata into two subcategories: metadata for reuse and retrieval, and metadata for tracking.

Descriptive or publication metadata

Today, if you go into a number of libraries, you’ll find that the information (books, magazines, and other nonprinted material such as videos and multimedia assets) are organized in a fairly consistent manner from one library to the next. It wasn’t always this way.

For centuries, individual libraries were organized by whatever scheme the chief librarian was comfortable with. That’s not to say they were disorganized, but the librarian was free to categorize the information in the library in a manner that suited him. It might not be logical or obvious to someone familiar with another library’s categorization system, but it would be internally consistent within that library or within a related group of libraries.

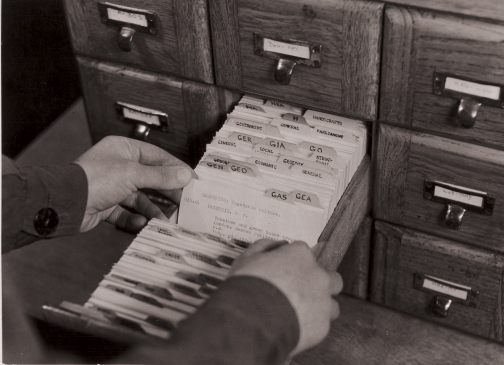

In the late 1800s, Melvil Dewey was put in charge of the library at Amherst College in Amherst, Massachusetts. Dewey was a born reformer and organizer, and within a few years he had devised his own system of categorization, now known as the Dewey Decimal Classification system. Many of us used his system when we searched through card catalogs in libraries (see Figure 15.7). He organized all the information in the library into ten top categories, with repeated subcategories to more clearly define and segregate more detailed information.

Figure 15.7. Card catalog.

This system spread throughout the world and remains one of the most common library categorization systems.

But why does it work?

The file cards contained information about the books that people were looking for, such as title, author, publication date, subject, and a brief description (abstract) of what was contained within the books. In today’s world, the items on the card would be referred to as metadata.

We use the metadata (embodied in the Dewey decimal system) to find the book. Although the days of the physical card catalog are largely behind us—with the physical cards being replaced by computer systems—it’s very difficult to find a particular book in a large library without resorting to the catalog. Walking back and forth up an aisle of books is time consuming and inefficient. Even worse, without metadata it’s nearly impossible to find content online (for example, on the Internet, a company intranet, or within a content management system). Online you don’t have the option of walking the aisles; you must use some form of search tool, and the best search tools are driven by metadata.

The increasing use of portals has encouraged organizations to make the portal the central location for access to organizational content. However, as each new piece of content is added, customers’ ability to find content decreases. Corporate information needs to be just as accessible as library content, which means organizing content in a logical structure, categorizing it, and using the categories to add metadata to the information. Descriptive metadata is like the old card catalog, presenting information to customers in context and enabling them to quickly find relevant information.

Creating descriptive metadata

Often it’s the job of a corporate librarian or information architect to manually identify and tag content appropriately. Corporate content can be any content the corporation creates, receives, or wants to make available to its employees, customers, or suppliers. This body of content is much broader than the content we refer to in this book; it encompasses email, reports, correspondence, strategic analysis, and much more. The volume of this content grows at a tremendous pace, making it difficult for organizations to maintain it manually.

If you have a lot of content to categorize, check to see whether a vertical taxonomy already exists for your industry, and check with vendors to see whether they can support your information set. Creating descriptive metadata is a large, sometimes costly, and intensive ongoing task. If you don’t have to do this task on your own, don’t try to. If you do decide to tackle the job, consider including corporate librarians or information architects on the team.

Understanding your customer

To begin the process of creating descriptive metadata you need to understand your customers. You need to know who they are, what they’re trying to accomplish and how they’re looking for information.

• Who are your customers and what are they trying to accomplish?

Are they prospective purchasers? Are they comparing your product to your competitors’ products? Are they looking for reviews? Have they already purchased your product and begun looking for accessories?

You’re likely to find that you have more than one set of customers (or audience) for both your product and your content. You can use that to your advantage, and learn from it.

Because each audience is slightly different they will be interested in different things. Some will be focused primarily on price, others are more interested in particular features. Still others might want your product immediately, so they’re focused on current availability.

Prospective purchasers might share some interests and concerns with existing customers (availability of accessories). On the other hand, while prospective customers might be interested in the size or weight of your product, existing customers (who already have your product) probably won’t be.

• How are they looking for the information?

If people are searching the Web, they’ll use some form of search engine and type a word into the search field that they think will help them find what they’re looking for.

For printed content, people use the index like a search engine, but rather than typing in a search word, they look for the word in the index, and then turn to the page they think is most likely to contain the relevant information.

You want to ensure that the search terms people enter online or look for in an index lead them to the information they need. It’s difficult to anticipate what search terms people will use, but if you’ve thought out who’s searching for your material and what they’re trying to do, you have a much better chance than if you guess.

Think back to your analysis of who your customers are and what they’re looking for. Ensure that your content has been tagged with the terms that the various sets of customers are most likely to use as search terms.

Categorize your content

The next thing you have to do is to group or categorize your content. Why?

Imagine you want to find a photo on your computer. If you know the name of the photo, you can search for it pretty easily. Just type the name (or part of the name) in the search box. But if you have a lot of files on your drive, it’s going to take some time. If you have a bunch of files that share a part of that name, you’re not only going to get a long list of possible files, but some of them might be documents, others spreadsheets, and others pictures or movies.

You can speed things up by ensuring that you limit the search to only photo files such as JPEGs. Tell the search tool on your computer to look only for files with the .jpg file extension, or only “files that are photographs.” Now instead of looking at all the files on your computer, it only has to look at photo files.

Congratulations—you’ve performed what taxonomy geeks call a “faceted search.” Facets are what normal people call categories or groupings.

If you examine your material, you’ll find that you have common groups of information. Start by identifying these.

Grouping or categorizing related content

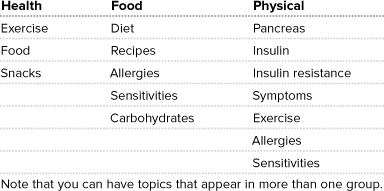

As you start to examine your content, you’ll probably find content that covers a broad range of information. For example, a quick perusal of the glycemic index (GI) content shows the following topics, among many others (see Figure 15.8).

Figure 15.8. Topic cloud.

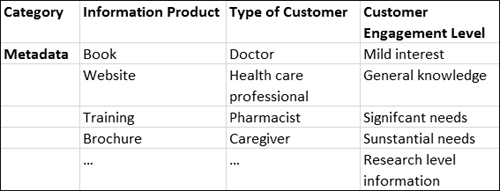

These could be grouped in many ways, as shown in Table 15.1.

Table 15.1. Topic categorizations

Finding existing categories

Often the best categories are ones that already exist. Look at how websites are organized, and look at existing libraries of information. Talk to information architects, writers, and trainers. If you can, talk to your customers. If you can’t, speak to people who work with your customers and find out what people are looking for. Don’t forget to look at material provided by your competitors, for example, look at their website to see how they organize it. The goal isn’t to copy their organization, but to observe and understand how someone else looks at and categorizes similar information.

Talk to the people in charge of your website (or websites). Websites are a bit like an iceberg: when you visit them, you’re only seeing the tip of the information that’s really there. Behind that website is a vast trove of information, which can be accessed by web analytics.

Web analytics gather information about the visitors: what search tool they used to find the site, what keywords they entered to get there, what pages and products they were most interested in, and what products or information no one appeared interested in.

Each piece of information you can gather helps you make good decisions about how to categorize your information to make it easier for your customers to find it.

Too much information?

You might find, after researching existing categories, that the problem is that there are too many categories, too many ways of organizing and storing information, rather than too few. There are ways of comparing them, the most common being known as a crosswalk. A crosswalk can be used to compare information at the top or at the more detailed level of component metadata. For more details, see “Crosswalk,” later in this chapter.

Component metadata

Component metadata has a different focus than descriptive metadata. Whereas descriptive metadata is designed to help customers find completed content, component metadata helps content creators find information before it’s published. In particular, it allows content creators to find information at the component level so it can be used in multiple outputs.

There are two main types of component metadata:

• Reuse and retrieval metadata

• Tracking or status metadata

Reuse and retrieval metadata

This first type of component metadata is designed to help authors find content so they can use it in multiple areas. Before even beginning to write, authors can search the content management system (narrowing the search results by picking the applicable metadata) to find reusable content. For example, if an overview already exists for Product 1, you can use metadata like “content type = overview, product = Product 1” to help you find the correct content to reuse.

Alternatively, the content management system can automatically search for appropriate reusable content (based on models and metadata) and deliver it (automatic reuse) to authors. In both cases, metadata is very important to correctly identify the components of content.

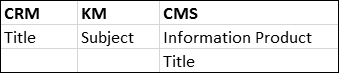

As with categorizations, where different departments often have competing views on how the information should be organized, those departments may also have different sets of what might be considered component-level metadata. Sometimes it’s formal metadata; most often it’s just what people call things.

Only in the rarest of cases will these multiple worldviews match. Marketing may refer to something as a Title, while the service people refer to the same information as a Subject. As we first noted in the explanation of what metadata is, metadata has to be consistently applied to be useful.

When you find these inconsistencies, you can apply a crosswalk to compare them and help sort out the differences.

To determine what metadata you need to enable reuse, you need to first determine the business result you’re trying to achieve and build your metadata backward to achieve that result. Think about the following.

Where is content going to be reused?

Across product? Across information product? If you answered “yes” to either of these, then you need to create metadata to identify each reuse, for example:

Product, such as:

• Product 1

• Product 2

• Product 3

Information product, such as:

• Marketing brochure

• Web

• Training course

• Marketing copy

Note that metadata such as information product can be derived from the template type.

What type of content is it?

You also need to know the component content type for which the content is valid. Your metadata might include Content type, for example:

• Concept

• Task

Note that metadata such as content type can be derived from your component model or semantic tags.

What else do you need to know about the content to ensure that the correct piece of content is reused?

You may need to know the region or location where the product is being sold or used so that you can identify content such as safety regulations, language, and configuration. In this case, your metadata might include geography metadata such as:

• Country level

• United States

• Canada

• South America

• Europe

• Language

• English

• Spanish

• French

• Italian

You may also need to know the audience so that appropriate content is provided for each audience:

• Audience

• Doctor

• Pharmacist

• Caregiver

• Patient

Some component metadata is the same as descriptive metadata. Both customers and authors might want to find information by the title, by the author’s name, or by a specific keyword. Both component and descriptive metadata can contain these metadata components; the crucial difference is that in component-level metadata the metadata is applied to the individual reusable components, not to the completed product.

• Title/Subject

This type of metadata can be entered by the author, or the system can use the title that appears in the content to create this metadata.

• Author

The system usually generates this type of metadata automatically, based on the author information.

• Keywords

This metadata can be entered by the author; however, it’s preferable to provide the author with a list of keywords from which to choose, which ensures that keywords will be used consistently.

Not all component metadata is the same as descriptive metadata. Because the component metadata is usually used within a controlled authoring/editing environment, some metadata isn’t applicable to the general public. For example, the system has to be able to determine if a particular author can see the available reusable components. If an author does have permission to see them, access is probably limited to viewing the components, with no permission to change them. The level of access that people have is determined by a security policy, and that policy is managed by the application of metadata.

• Security level (who can view the content)

This type of metadata is usually applied by the author from a selected list of options.

Metadata for tracking (status)

Metadata for tracking is particularly useful when you’re implementing workflow as part of your unified content strategy. By assigning status metadata to each component, you can determine which components are active. You can also control what can be done to a component and who can do it. Generally, status changes based on the metadata are controlled through workflow automation, not by customers. Sometimes, though, an author will identify a status change such as “Ready for review” because the system can’t automate this type of information. Status metadata can include such tracking items as Draft (under development by the author), Ready for review, and so on.

Again, as with your other metadata, you identify tracking metadata by determining the business result you’re trying to achieve, and then build your metadata backward to achieve that result. Design your metadata for tracking after you’ve designed your workflow (refer to Chapter 14, “Designing Workflow”). This enables you to identify what metadata needs to be applied to the content at each stage of workflow to enable the workflow system to manage it.

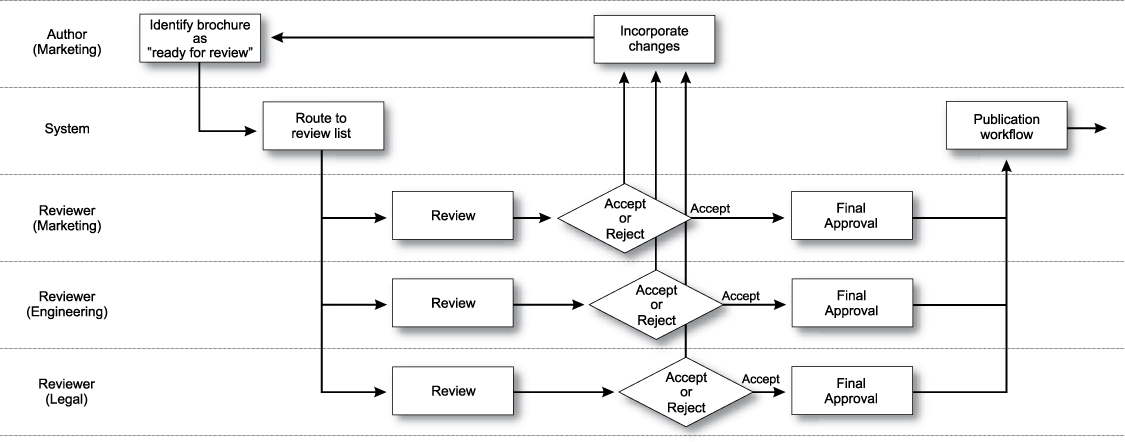

For example, the metadata for the review and approval workflow shown in Figure 15.10 could look like the following:

• Content status

Indicates the status of the content. Before it can be reviewed the content must have the appropriate metadata attached to identify that it is ready for review. For example, the metadata could include:

• Draft

• Ready for review

• In review

• Final

• In approval

• Approved

Figure 15.10. Review and approval workflow.

When the content is ready for review, authors apply the “Ready for review” metadata. When the content includes the feedback from review and is ready for final approval, authors apply the “Final” metadata. When the final approval reviewers approve the content, they apply the “Approved” metadata.

The system needs to identify the status of the content at any point in time. When the content has been passed to review, its status is automatically changed to “In review,” and later, when it’s passed on to final approval, the status is changed to “In approval.”

• Review status

Indicates the status of the review content. A reviewer can either accept the content without changes or reject the content by asking for changes and returning it to the author. For example, the review status metadata could include

• Accept

• Reject

If the metadata is “Accept,” the system moves the content to the final approval stage, but if the metadata is “Reject,” the content is routed back to the author for changes.

Tracking metadata

After you’ve designed your metadata to support your workflow, you need to identify other metadata that can help you track your content. For example:

• Who created the content (author)?

• When was it created/modified (date)?

• Who modified the content (editor)?

• Who reviewed/approved the content (reviewer/approver)?

• How long did it take to create/modify/review (time)?

• Where has it been reused (information product, product)?

• Has it been translated (content status)?

Most content management systems automatically create some of this metadata (for example, author, date), whereas other metadata may already be defined in retrieval metadata and reuse metadata. We recommend that you go through this exercise to make sure that you’ve identified all the possible metadata you require for tracking and reports.

Metadata relationships

Component and descriptive metadata are closely related. In some cases, even the names are the same, but it’s applied to different content.

For example, a particular author may have written all the content for a brochure and therefore the author’s name was associated with all the components that make up the brochure. As the brochure works its way through the creation, revision, approval, publishing, and distribution process, it’s easy to promote that author’s name from the individual components to the categorization or product level. If there’s more than one author, the system can gather them all and roll them up into a list of authors.

Other types of metadata are similar but applied at different levels. Separate creation, revision, and approval dates would be managed and tracked for both the individual components and the final publication. Each of the metadata elements has the same name (Date = Approved, for example), but they’re maintained separately.

Summary

Metadata is critical to the success of your unified content strategy. It’s more than just data about data; it’s the encoded knowledge of your organization. Metadata can be used to describe the behavior, processes, rules, and structure of data as well as add descriptive information.

Descriptive metadata categorizes your documents and is usually used by content users to retrieve content.

Component metadata identifies your content at the element level and is used by authors to retrieve content components. There are three kinds of component metadata. Metadata for reuse is used to identify the components of content that can be reused in multiple areas. Metadata for retrieval is used to retrieve content. It may consist of metadata for reuse as well as additional retrieval metadata. Metadata for tracking (status) is used to identify the status of your content in a workflow system.

To define your metadata, start by identifying the business result you want to achieve with your metadata and work backwards to identify what metadata will achieve that result.