2Text Linguistic Approaches I: Analysis of Media Texts

Abstract: Text linguistics as one key discipline in linguistic media research is nowadays challenged with an increased complexity of its subject. Media texts in tertiary media are often multimodal and address various semiotic dimensions through (hyper)text, moving or still pictures, sound, and graphic effects. This article outlines theoretical approaches to the analysis of media texts in the era of multimodality with a focus on film and television text, which are usually characterized by linearity and a separation of the producer and the receiver, as well as hypertext, which is characterized by nonlinearity and interactivity. Borders of texts, especially in online contexts, are becoming more and more blurred and require new analytical approaches.

Keywords: film, hypertext, interactivity, linearity, multimodality, television, text linguistics

1Introduction

It is a generally accepted assumption that due to recent and ongoing technical innovation, text and media text are undergoing profound changes which interact with alterations in society. The general claim of the growing “visuality of society” indicates the nature of change that not only society but especially communication and text are experiencing (cf. Sutter/Mehler 2010): Lesser importance is being given to the written word, whereas other semiotic modalities, mainly visualization and design (cf. Eckkrammer/Held 2006, 1) take over the “informational weight” and seem to make written information almost superfluous (cf. Eder/Eckkrammer 2000). The dynamism of media change is bound to technical innovation. Research areas such as media studies, cultural studies, and linguistics are in the process of modeling the textual and linguistic innovation that emerges out of the processes of technological progress. Text linguistics as area of linguistic research that traditionally takes into consideration the complexity of language use in communication is the genuine field of research and theory-building that responds to the mentioned changes.

An overview of relevant literature on language and (new) media in general suggests a classification of the existing work roughly according to:

1)models based on analysis of linguistic features of language and variety use in distinct media formats, such as television and computer-mediated communication,

2)text linguistic models which shape media text as an extension of features of traditional text and

3)theoretical approaches that perceive media text as requiring complex new models.

As the title of this chapter suggests, the focus here is on text linguistic approaches, including (2) and (3). Text linguistic approaches have to be considered as distinct from linguistically-inspired media study or cultural study accounts mainly because they elaborate not only theoretical models but make available systematic methodological suggestions for empirical text linguistic work. Desiderata lead us to pay attention to studies that emerge in fields other than Portuguese and/or Spanish studies in order to provide perspectives for future work for these contexts.

The emerging dynamic multimodal text realities of modern societies are interpreted in terms of the “turn”-vocabulary, such as, e. g., the “iconic turn” (cf. Burda/Maar 2004), the “visualistic turn” (cf. Sachs-Hombach 2005; 2009), the “multimodal turn” (cf. Bucher 2010). Generally, claims for modeling these new text realities evoke ideas about an ongoing media-text revolution that raises many new questions for the field of text linguistics. Indeed, some have argued that in light of the transformations, the name of the field should itself be changed to “text semiotics” (cf. Eckkrammer/Held 2006). The seminal work of Kress/van Leeuwen (2001) supports the idea of a decisive change by claiming that western culture for a long time was marked by its preference for monomodality. Multimodality is thus conceived of as a recent phenomenon. However, there are more “traditional” multimodal text types such as comics, film, photography, even, for example, paintings in the context of an exhibition (cf. Pang 2004). Their existence previous to new media texts suggests that text linguistics hitherto has delimited itself deliberately by focusing mainly on monomodal texts or even on multimodal texts, but, from a monomodal point of view.21 Notably, multimodal accounts did exist before the “revolution” of media text: Film theory is an appropriate example for a longer tradition of multimodal approaches as from its very beginning it has established a strong relationship between film and text and the concept of “film text” (cf. 3). Nevertheless, although the phenomenon of multimodality is rooted in earlier text types, new multimodal communication forms and technical possibilities inspire new perspectives on the phenomenon. One of the innovations in text linguistic approaches to media text in general is derived from the text linguistic criterion of intertextuality and becomes manifest in a strong and consistent focus on network (cf. Mehler et al. 2008; Bucher 2013) and relational meaning making (cf. Wildfeuer 2014, 1) not only within the field of text linguistic approaches to film (cf. 3) but also in hypertext linguistics (cf. 5). This focus goes beyond text linguistics or text semiotics in a strict linguistic sense of the concept. It is related to neurophysiological-oriented assumptions about the working of the human brain and to sociological assumptions about the operating of human social relations. Thus, the interdisciplinarity of the field nowadays goes hand in hand with research progress in other fields that are also dependent on technical advances, as is the case in neurophysiological research.

This chapter will consider text linguistic access to media text, taking into consideration mainly newer perspectives on “film text” (3), TV text (4) and hypertext (5). Due to the dynamics of technological development and accompanying innovations in computer-mediated communication and media text, the chapter has to be delimited to a record of the state of the art valid for the very moment of its elaboration.22

2Media Text and Text Linguistics: Main Questions and Concepts

Notably, technology plays the fundamental role in characterizing new “tertiary media”. A basic difference to other types of media is the new form of access to information presented on a screen, which implies new forms of information arrangements (cf. Eckkrammer/Held 2006). As a consequence, tertiary media text has to be considered as recontextualizing traditional forms of texts in new opposition relations as for example the very basic one between a paper text and a screen text.

Due to the nature of technically-mediated texts, this apparently rather material difference raises fundamental questions about the conditions and modes of perception of text conceived as a “Sehfläche” [‘visual surface’] (cf. Schmitz 2011). Recent neurophysiological research explores, for example, differences between text perception and understanding text on computer surfaces (e. g., iPad) versus on traditional paper surfaces.23 Among other results of a respective survey (cf. footnote 3), which benefits from interdisciplinary approaches in new media studies, users’ still existing opinions about and preferences for paper text are attributed to a specific tradition of text perception and reading culture which nowadays is in process of change. Brain waves indicate that the users’ belief that they understand better media on paper than a media screen text is not in accordance with their respective neurophysiological activity. Thus, apparently, media (text) change is responded to earlier by the human brain than by human consciousness.

Text linguistics has also responded to this recent media text change with a number of questions and concepts, some of which will be presented in the following. Generally, text linguistic approaches to (new) media texts are driven by the aim to retrace processes of meaning construction in complex linguistic entities, especially those of multimodal design. One of the main research topics consists in achieving adequate analysis methods that respond to the challenges of multimodal communication and information-transmitting processes. Multimodality is not comprehended as the sum of different modes to be explained separately from each other, but as generating intersemiotic processes emerging out of the interaction of different semiotic modes that lead to “relational meaning-making” (cf. Wildfeuer 2014, 1). The aim is to reach full comprehension of the interplay between the different semiotic modes both from the information producer’s and the receiver’s point of view. Part of the research question is to find out if and how relational meaning making in multimodal communication leads to new forms of knowledge transmission and even new forms of knowledge. These questions indicate that text linguistic approaches to multimodality are driven by deeper interests than just describing new textual modes of communication. There is much progress in proposing and refining research and analysis methods that support the exploration of the different and complex ways and processes of meaning-making and “meaning multiplication” (Bateman 2014, 5ss.).

The outcome of this dynamic interaction between (new) technical media and traditional forms of communication, i.e., the convergence of technical media and communication forms (cf. Bucher 2010; Stöckl 2012, 19), are different types of media texts of high semiotic complexity which include, for example, bimodal texts, multimodal texts and hypertexts. Thus, definitions and concepts of “text” as one of the core topics of text linguistics are challenged by the emergence of technology-based text types. As a consequence, one of the main problems of text linguistic approaches to media texts is the question of how to come to grips with a text concept that takes into account the above-mentioned specific, changing and dynamic features of media texts. Up to now, these are mainly the questions of relations between:

1)text and image,

3)text and other modalities of communication (sound, motion etc.),

3)non-linearity, associative array of information and/or

4)the interplay of these features within one “text”.

Technical developments in the field of computer-mediated communication lead to new possibilities and high frequency of bottom-up multimodal interactive text production and reception which requires modified approaches to text linguistics. As to the basic concept of text, text linguistics still pays attention to criteria of textuality as established by Beaugrande/Dressler (1981), often narrowing the list to cohesion and coherence as the most relevant criteria as suggested by Vater (2005). However, as a starting point for text linguistic approaches, the whole catalogue of seven criteria (Beaugrande/Dressler 1981) is also often taken into consideration, as in the case of empirical research on (new) media textuality (cf. Eder/Eckkrammer 2000, 39; Huber 2002; Stöckl 2004) also called “elektronische Textualität” [‘electronic textuality’] (Eder/Eckkrammer 2000, 33). Here, on the contrary, criticism to the model leads to broadening the catalogue, which results in an even larger list of text features that determine textuality. New media require new criteria and distinctions as the one between prototypical and peripheral (subordinated) criteria (cf. Stöckl 2004, 100). In view of the increasing frequency of phatic communication in new media, such as communication in chatrooms and discussion forums, the criterium of informativity, also part of the Beaugrande/Dressler catalogue (1981), raises new distinctions of different degree between the two poles of textual informativity and “disinformativity”, (cf. Eder/Eckkrammer 2000, 10), i.e., the amount of text production which is not supposed to contain information but is rather to be understood as phatic communication.

The question of classifying texts according to text types remains an exhaustive ongoing discussion in “traditional” text linguistics, let alone in approaches to new media texts. One of the basic questions concerns the relation between old text types and new text types. Do we deal with a continuation of existing text types, their production and reception under different technical conditions as for example indicates the research on cooking recipes and contact announcements in Eder/Eckkrammer (2000), or do we deal with the emergence of new text types? Not surprisingly, the observation of the general principle of change and continuity applied to the relation between old and new text and communication forms is rather part of earlier work on text pattern and typology which focuses on new media texts at the beginnings of their appearance. In their study on job advertisements, Eder/Eckkrammer (2000, 192) indicate that with regard to this text type, which has like others undergone a change from print media to hypertext publication, the traditional features of its paper form are found also in its hypertext publication, though the screen mask has consequences for text structure and influences and changes text pattern conventions.

More recent work focuses directly on questions of classification of bimodal (or multimodal) text patterns (cf. Stöckl 2004, 113; 2006, 13). Relying on basic distinctions between technical medium, communication form, multimodal text and semiotic modality, put into hierarchical order, Stöckl (2012, 19s.) deepens this complex task. With reference to semiotic modalities, he distinguishes three main media text types:

1)print media including writing, static picture and typography,

2)audio media including spoken language, music, noise, and,

3)as the most complex form of media text, audio-visual media which comprises spoken and written language, static and dynamic typography, static and dynamic picture, music, and noise.

His basic schema can be applied to empirical work on (new) media text typology and lead to further typological distinctions related to topic, function and/or type of topic development.

3Textuality and Multimodal Analysis of Film: The “Film Text” Approach

Film is considered to be one of the most important and “powerful contemporary text types” (Wildfeuer 2014, 19). Although sharing features and aims of text linguistic approaches to media text which seek to analyze and understand meaning construction in film, the original concept of “film text” did not arise out of a text linguistic context in the strict sense of the term. The concept is connected with the name and the work of Christian Metz (1971), a film theoretician and semiotician, today usually mentioned and critically discussed in introductory parts of studies on the subject. “Film text” was related to the idea of “film language” and intended to get a better understanding of the structural conditions of meaning construction and communication within a linguistically-inspired model of syntagmatic relations in film.24 Notably, this early theoretical perspective on film and its empirical consequences were based already on technical development and corresponding new possibilities of watching single parts of the whole film repeatedly (cf. Blüher/Kessler/Troehler 1999, 3), which allow analysis. Also, they were already focused on the multimodal character of the “film text”. However, because of – from today’s (text)linguistic point of view – the limited linguistic value ascribed to the model, it rather contributed to film theory than to text theory or (text)linguistics. As such, Metz’ approach had strong influences on research on film in France, Great Britain and the USA, whereas German film theory didn’t take into consideration much from the ideas that arose from Metz’ work (cf. Blüher/Kessler/Troehler 1999). As Bateman (2014) points out, this was also due to the contemporary linguistic mainstream characterized by a limited focus on language. As to Spanish film studies and analysis, only recent references to Metz (1971) are giving evidence that his work is still being perceived by scholars (cf. García Escrivá 2011, 84), although not going far beyond the original frame, as for example, taking it as only a starting point to develop a text linguistic approach in the linguistic sense of the term.

The “film text” idea is currently being picked up in Germany by an interdisciplinary project with a strong text linguistic focus. Textualität des Films [‘Textuality of film’] is, probably, the most recent, thought-out text linguistic research account where the well-known notion of “film text” reappears in a linguistic perspective, especially in Bateman/Kepser/Kuhn (2013) and Wildfeuer (2013a and 2014)25. Although so far no text linguistic analysis of Spanish or Portuguese film can be identified within this new approach, it is worthwhile to discuss it here in order to instigate studies especially in the field of the textuality of Spanish and Portuguese film which could lead to working out culture-specific features of “film text” both in the European and the Latin-American context.

The approach offers a stringent methodology of analysis26 which could stand up to comparative textuality studies, hitherto only realized in the field of specialized text and not text linguistics (cf. the project Kontrastive Textologie [‘Contrastive Textology’], cf. Eckkrammer 1999). It stands for a general turn of linguistics towards a wider idea of text which comprises two main perspectives on text: the one that parting from the text as a static object of linguistic interest opens the concept to a dynamic text concept, and the one that exceeds the limits of the spoken/written word and includes semiotic modes such as static and/or moving pictures, noise, camera move, etc. “Film text” theory and research today goes hand in hand with research on multimodal items (cf. Kress/van Leeuwen 2001) and is defined as follows:

“[…] a multimodal text which is meaningfully structured by a variety of semiotic modes. It is a dynamic but formally confined artifact in chronological, linear order. It may have intertextual references to further text types and may produce various communicative intentions according to the context” (Wildfeuer 2014, 10).

“Meaningfully structured” gives a hint to one of the hitherto main foci of the approach, the analysis of multimodal cohesion means and coherence structure called “film discourse relations” (Wildfeuer 2014, 11s.).

In order to give an overview of the whole analytic dimension of “film text”, Wildfeuer (2013a) offers the following schematic representation which comprises traditional linguistic and textual criteria such as semioticity, coherence, and intertextuality, and more specific ones such as linearity, multimodality, and dynamicity (cf. Figure 1).

In the following, the single aspects will be shortly presented and discussed: The text linguistic criterion of ‘semioticity’ (Semiotizität) comprises aspects such as ‘communicative function’ (kommunikative Funktion) and ‘situationality’ (Situationalität) of film text. One of the key concepts is ‘multimodality’ (Multimodalität) which in this schema refers to the complex possibilities of interplay between auditive means, visual means, action, and its contribution to meaning construction. As such, multimodality opens a field of research topics such as types of film music, synchronicity vs. non-synchronicity of music and picture and, generally, the degree of integration of multimodal means in filmic action. Film text contrasts with other multimodal texts as, e. g., texts in new media, which are characterized by interactivity in production and reception (cf. 5). Thus, film is bound to ‘linearity’ (Linearität) and also characterized by ‘non-interactivity’ (Nicht-Interaktivität). Notably, this criterion refers to a “traditional” concept of film to be watched in cinema.28 As in verbal text, ‘coherence’ (Kohärenz) refers to the structural character of film text (Strukturiertheit) and is considered to be constructed by the producer of a film as a set of strategies with the function of channeling active processes of coherence reconstruction by the film audience. Different from verbal text, it is considered to be co-constructed by different semiotic means and thus challenges methodologies of analysis. ‘Dynamicity’ (Dynamizität) comprises aspects as temporality, successivity and montage of the “film text”. The very complex aspect of ‘intertextuality’ (Intertextualität) is not yet especially worked-out and opens perspectives for further research. Existing research on this subject, including related linguistic topics such as polyphony and evidentiality, and their realization within multimodal means, can contribute to deepen film text studies on this topic.

One of the most important characteristics of this schema is the interconnection of the different aspects of the “film text”. From the receiver’s point of view, this corresponds to the process of intersemiosis, which refers to the interaction between the different aspects in the process of meaning making. At the same time, while keeping in mind the logic of the whole, the model allows to highlight and to work out only parts of the whole within an empirical analysis. Methodological steps to analysis are explained in detail in Wildfeuer (2014, 32ss.) and, by means of a model analysis of the film “Das Leben der Anderen” [‘The Lives of Others’, Henckel von Donnersmarck 2006] (Wildfeuer 2013a). Methodology within the focused approach comprises, e. g., modes and manners of transcription of sequences of film and its representation in tabular form. Transcription as first step of multimodal “film text” analysis is an especially complex undertaking. It is based on the film shot as the minimal unit of analysis, and comprises the visual and the auditory track with corresponding submodes such as static and moving picture, camera movement, music, speech, and so on; a schematic model to present the transcription is given and explained in Wildfeuer (2013a and 2014). Further steps of analysis on different levels such as the visual level, the auditive level, and analysis of salience (foreground vs. background) including the different respective sub-levels can be traced following the step-by-step analysis of the mentioned film.

In view of new representations of film, part of the criteria of film text above presented and discussed have to be modified. This concerns mainly the criteria of linearity and non-interactivity which are changed into their opposite, i.e., non-linearity and interactivity, in the genre of the “new interactive film” (cf. Wildfeuer 2013b) to be found on the Internet. As the notion of “cinematic hypertext” (cf. Miles 1999; Wildfeuer 2013b, 65) suggests, it converges with concepts and characteristic features of hypertext (cf. 5). The “new interactive film” is found on Internet platforms like YouTube (and others), and is characterized by offering to the receiver different technically-supported possibilities to intervene in the linearity of the filmic narration and create their own film text. Due to the innovative character of this film genre, further research is a desideratum.

Mainly from a media studies and even applied media studies perspective (cf. Santanilla Cala 2009), but hardly from a linguistic point of view – in Spanish and Portuguese film theory and analysis the notions “film text” and “textual analysis” are also being used (cf. Gómez Tarín 2006; García Escrivá 2011). However, no text linguistic model of analysis in the strict sense of the term is applied. As there are translations into Spanish, theoretical studies are linguistically-inspired by Metz’ work (cf. Gómez Tarín 2006). Film analysis is made mainly with the aim to understand better the filmic narrative based on Aumont/Marie (1988). Notably, Gómez Tarín (2006) mentions Kristeva’s concept of intertextuality (cf. Gómez Tarín 2006, 9), which could be a starting point for deepening this very aspect in film analysis. This specific stance on intertextuality opens a perspective on intertextual and/or discursive accounts on “film text” to be further in a text linguistic perspective.

4Television text

As Hickethier29 (2010, 109) emphasizes, television text presents a similar, but far more complex form of media text than film and thus has to be approached by different and additional means of textual analysis. The concepts of “film text” analysis can be transferred to TV text, yet some special features suggest an expansion of TV text analysis from text to intertextual and transtextual relations, which leads to discourse analysis of TV text. Discourse here is not to be understood in the sense of a macro text as González Requena suggests (1988, cf. below), but in the sense of linguistic discourse analysis according to Michel Foucault (cf. Spitzmüller/Warnke 2011). The relation between text analysis and discourse analysis is especially interesting for topics such as coherence structure in TV formats (cf. also Hickethier 2010, 101) and various facets and levels of inter- and transtextuality. It comprises the wide range of topics from “paratext” to TV text formats and, regarding different subject matter and transtextual relations, as for example, Vergara Heidke (2010) shows in a TV text analysis of criminal discourse in Costa Rican television news. As these topics represent TV features that do change in time, they are also interesting for diachronic studies relating them to changes in media text, media language and their relation to changes in society.

“Paratext” has its origin in Genette’s intertextuality theory (1987) and refers to any additional text produced in relation to a specific main text. Its functions are defined as presenting the main text, controlling the receiver’s expectations and the reception of the text itself (cf. Hickethier 2010, 103). Types of paratext in TV, for example, are the multimedia announcements of TV programs. As they are published in newspapers, journals, Internet and TV itself, they generate intermedia and intersemiotic relations between different media texts and media resources (written language, picture, voice, music, etc.) and thus can also be analyzed according to the coherence structures they channel. As to the intertextual phenomenon of TV formats, a basic distinction is made between TV “film texts”, such as TV film and telenovela (cf. below), “live texts” such as news broadcasting (cf. below), and combined texts (cf. Hickethier 2010, 110ss.).

In the context of research on TV text in Spanish and Portuguese language, TV discourse and, for example, telenovela as a mainly in Latin America relevant important form of “film text”, and news broadcasting as “live-text”, have received much attention from education studies, media studies and sociology and less attention from linguistics. Due to the complexity of language use in TV, in Spanish media theory, academics disapprove of the notion of “TV language”, which they think leads to focus attention on “TV discourse”, here understood in the sense of TV text. Linguistic work itself pays much attention to aspects of TV language and lesser attention on text linguistic problems. Spanish and Portuguese TV language studies focus on specific aspects and questions concerning language and variety use and their relation to and influence on political power, social distinction and identity (cf. Bachmann 2010; 2011a and 2011b; Hofmann 2011; Porto 2012).

According to the approach of González Requena (1988, 30), TV text is considered as a “macrodiscourse”, a global macrotext, characterized by a “presencia simultánea de la fragmentación y la continuidad”30 (cf. also Eckkrammer/Held 2006, 5) on this aspect in new media text) and by a “coherencia textual profunda”31 (Aguaded Gómez 2000, 5). Although the idea of a global TV macro text which makes cultural differences fade away in TV formats may respond to observations on the reality of globalization effects on media texts, it does not offer a methodology for systematic text linguistic analysis. A stringent methodological approach that would highlight the complex cohesion of a TV series such as the telenovela keeps being a desideratum. However, taking into consideration that TV text today very often forms part of an expanded concept of hypertext, its analysis could profit from “film text” as well as hypertext theory and methodology.

5Text and Computer-Mediated Communication: The Hypertext

Notably, the new, Internet-based manifestations of the hitherto discussed media text formats converge in the concept of hypertext, which seems to be the most comprehensive concept of tertiary media text.

Considering the question of how text meaning is constructed as part of text linguistics, hypertext linguistics contributes certainly with new insights in new forms and processes of meaning construction which could enrich also traditional text linguistics, and especially text concepts. Structure of texts and possibilities of intertextuality, as well as combination between text and image, and the dynamic interactivity of written text, are some of the specific aspects of textuality of new media texts which sometimes raise the question of the end of linearity.

Whereas text linguistic approaches to film – as shown before – go far back to the beginnings of film analysis, hypertext is a fairly new communication form and object of text linguistic analysis. As a computer-mediated form of communication, it matches – at least in its written form – more obviously with the traditional concept of “text” than film does. However, its characteristics re-raise questions about text definition in general and hypertext as a legitimate object for linguistic research; in Spain – as well as in Germany – these kinds of questions mark the beginnings of linguistic work on the topic (cf. Almela Pérez 1999; Huber 2002, 1; Jakobs/Lehnen 2005, 160). Complaints about the lack of text linguistic studies on hypertext were expressed already in 2005 (cf. Jakobs/Lehnen 2005), notably in the context of Spanish and Portuguese language, and this kind of study remain a desideratum.

Hypertext cannot be determined as a proper text type. Rather, it is understood as a generic term comprising a wide range of different texts organized by distinctive features which can be grouped around hypertext types (cf. Jakobs 2003; Jakobs/Lehnen 2005, 163ss.); a notion which by itself suggests an advanced process of conventionalization of respective text patterns (cf. Eder/Eckkrammer 2000, 13ss.; Jakobs/Lehnen 2005, 163). Hypertext with its characteristics contests traditional text types also in the field of scientific writing, as illustrated by a doctoral thesis on the topic (Lamarca Lapuente 2013) which designed itself as hypertext. Special features are, for example, the indication of the publication date as update, and a sophisticated inner textual linking system. Its dynamic and interactive form stands in an obvious contradiction to the traditional text type of a doctoral dissertation, and thus opens a perspective of expanding traditional forms of text to hypertext.

From a rather technical point of view, the linking principle introduces a function-oriented hypertext terminology: texts are referred to as knots which are related to each other by links (cf. Huber 2002; Jakobs/Lehnen 2005, 160; Mehler et al. 2008); the text-reception process is considered to be guided by a choice of reading options indicated by the linking system of a text called text navigation. Hypertext linguistics however does not make much use of these terminological innovations of the technical vocabulary; their use is rather a feature of specialized interdisciplinary work such as text linguistic computer science (cf. Huber 2002) or cognition oriented (hyper-)text linguistics (cf. Mehler et al. 2008).

An attempt to develop a consistent hypertext model based on the text linguistic approach of Sandig (1997) is found in Jakobs/Lehnen (2005). The model is intended to relate text categories such as speech act and topic structure, patterns of sequentiality and formulation, to hypertext, including multimodality and interactivity as additional features and evidences further theoretical desiderata.

Recently, Bucher (2013) suggests a network concept for hypertext, expanding older concepts by emphasizing its multimodal character and arrives at a very complex and innovative theoretical and methodological approach. Distinctions are made between:

1)the linking of information chunks,

2)the social network character,

3)multimodality (text, image, voice),

4)interactivity and the overall dynamicity of hypertext as a result of the interplay between those factors.

The resources of hypertext go beyond the frontiers of text and, at a more theoretical level, lead to a new text concept which overcomes the idea of text as an object of study with well-defined “borders”. At the same time, referring to corpus constitution and delimitation and, reliability and validity of empiric research, new questions about the old problem of empirical databases arise. Analogous to the debordering of text, the growing complexity to be dealt with in empirical studies possibly leads to a debordering of the corpus itself. Solutions to resolve the problem of a well-defined corpus depend very much on the subject matter of the respective empirical research and cannot be suggested in a general way.

Passing the frontiers of text is organized within two dimensions, an intertextual dimension and a semiotic dimension (cf. Bucher 2013, 59). The intertextual dimension comprises the hypertext-specific distinction between the manifest text and the text the receiver is constructing by making use of linking signs. The linking principle, as the most prominent feature of hypertext, comprises operational and participatory signs (cf. Bucher 2013). Operational signs (links to further text) give text a new spatial dimension which can be related to the text criterion of intertextuality (cf. Beaugrande/Dressler 1981) or intermodality (cf. Kress/van Leeuwen 1996, 33; Bucher 2013, 73) and questions the traditional idea of linearity of text, text reception and textual representation of knowledge (cf. Huber 2002, 11). Links are participatory signs, and as such present a receiver-addressed offer to (inter-)activity and participation and comprise multimodal communication possibilities. An empirical approach to hypertext should then take into account the “complex multimodal action structure” (cf. Bucher 2013, 69) it offers. Action structure is the result of the receiver’s configurative and text generating action (cf. Aarseth 1997, 65) which consists of semiotic moves rather than representing navigation paths (cf. Kress 2010, 170).

As mentioned before, the notion of hypertext comprises different text types. Weblogs as one type of hypertext – generating as well a number of further subtypes (cf. Schlobinski/Siever 2005, 9) – have been described in an international comparative project (cf. Schlobinski/Siever 2005) including Spanish (cf. Franco 2005) as well as Portuguese (cf. Sieberg 2005) weblogs. Due to the book concept, they are treated in the wider context of “language and text” and as is often the case, linguistic and text linguistic features are not treated as mutually interwoven. Instead, text linguistic criteria appear as one part within a catalogue of several characteristics. Both articles are based on a Spanish respectively Portuguese blog corpus, provide an insight in relevant publications on the topic (state 2005) and, guided by a catalogue of features of hypertextuality, provide a more general description to the reader.

This kind of overall view, which is found in Spanish and Portuguese hypertext linguistic work (cf. Magnabosco 2010), is not yet complemented by systematic text linguistic empirical research such as comparative hypertext analysis. In Spanish as well as in Portuguese, there is a strong focus on online newspaper texts as one type of hypertext (cf. Pérez Marco 2003; Canavilhas 2008; Vieira Barbosa/Barbosa de Sousa 2013). The approaches are less systematically text linguistic oriented, but ask questions about reader’s management of these interaction-requiring text types.

Hypertext production and reception favor the creativity of the “every day” text producer. In this context, a parallelism between the (hyper)text linking principle and the working of human intelligence, both generating links that bear meaning, is remarked (cf. Eder/Eckkrammer 2000, 34). New forms of knowledge are being generated via new (technology-based) forms of linking fragments of knowledge, thus written information nodes are being combined with links as a creative process of generating informative texts such as Wikipedia as a knowledge-oriented form of hypertext. By means of connecting (linking) chunks of knowledge, contrary to “film text”, new media texts are breaking with the principles of linearity. As Eder/Eckkrammer (2000, 41) emphasize, the linking principle bears efficiency of information-seeking and cognitive relief for the text receiver.

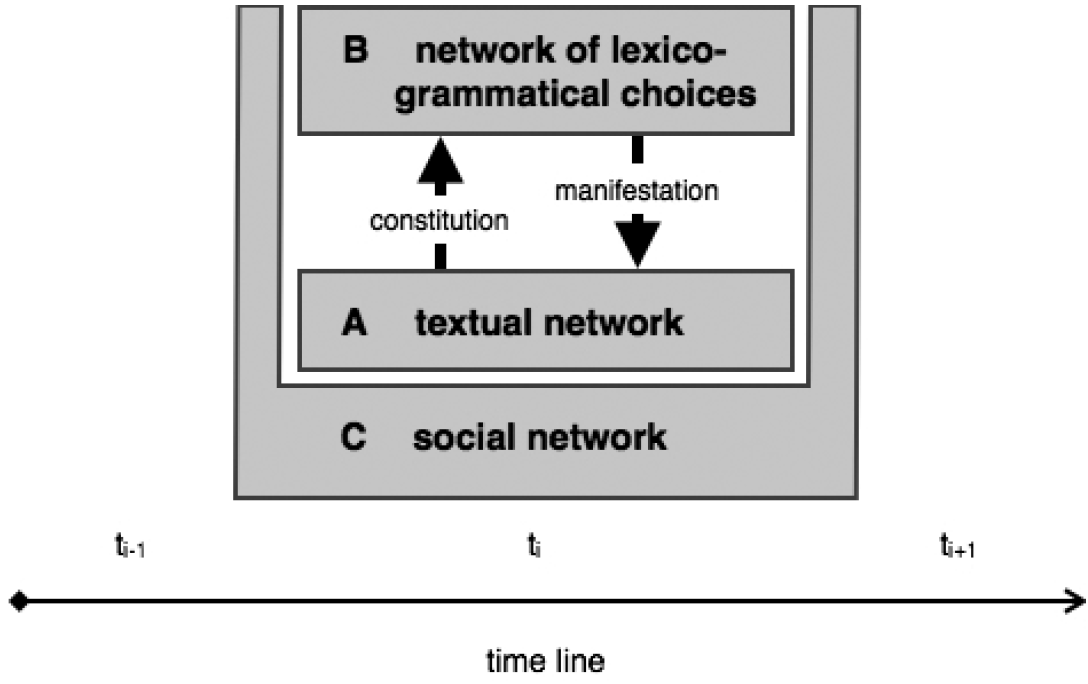

The cognitive aspect of knowledge production in hypertext is continued and methodologically elaborated in the textual network model of an interdisciplinary project on linguistic networks (cf. Mehler et al. 2008). As the title of this contribution – “linguistic network” – indicates, the main focus of interest lies in mechanisms of production of intertextuality as principle and main feature of hypertext communication. The linguistic background and research question behind is to obtain insight in processes of ongoing change in and diffusion of linguistic and textual routines and norms. The study is based on knowledge-oriented hypertext networks, with focus on Wikipedia and different types of Wikis, the presence of which on the Internet are a result of interactive production and reception of text within different forms and levels of intertextuality. The “discussion function” of Wikipedia is used to reconstruct text-building processes. Thus, interactively produced hypertext networks offer special forms of access to text, textual network, the processes of its generation, and therefore also technology-based possibilities of building a corpus that include the dynamics of processes of text production. As the schematic representation of the model shows, the intertextual levels to be explored are different types of networks that are produced and reproduced within the text building processes of the chosen type of hypertext and are linked to each other:

Whereas social network is not a recent concept, taking textual network and network of lexico-grammatical choices as basic units of (text)linguistic analysis is an innovative aspect and intent to respond to the special nature of web 2.0 communication (cf. Mehler et al. 2008). Notably, the model does not assume the notion of text, but of textual network, which inspires the idea of giving up the notion of text and to instead focus on textual network as basic unit for empirical analysis and theoretical thought and result of media change. Furthermore, the model integrates language use as a choice out of a network of choices of lexical and grammatical units which makes allusion to the discursive (and not exclusively lexical) meanings these choices may include.

Taking this model as a starting point, different forms of Internet-based communication can be analyzed according to the intertextual processes going on. It can be adapted to forum discussion (cf. Schrader-Kniffki 2012) as well as Facebook or blog texts and text networks.

6Conclusion

In this article, text linguistic approaches to tertiary media text were presented referring to film analysis, TV analysis and, hypertext. Notably, there are a number of desiderata in Spanish and Portuguese text linguistics which take into consideration and discuss recent approaches from other text linguistic contexts such as German and English text- and discourse linguistics regarding their relevance for and transferability to Spanish and Portuguese research on the topic. Wherever possible, studies from Spanish and Portuguese context were mentioned.

As to the single subjects that were treated, multimodality turns out to be one of the common grounds of and key notions for text in tertiary media. Multimodality nowadays is approached methodologically by refined methods that intend to respond to the complexity of a multimodal analysis by suggesting an – in relation to traditional text linguistic approaches – extended number of distinct categories and, as one of the most relevant points, trace interrelations between these categories. The understanding of relational meaning-making is a further and related common key notion of different approaches that leads to a preference of holistic perspectives on multimodal media text on the one hand and interdisciplinary research perspectives – including for example neurophysiological and computer science insights – on the other.

Further empirical research, especially in the field of European Spanish and Portuguese as well as Non-European Spanish and Portuguese linguistic and cultural context, is not only an urgent desideratum, but could also lead to further theoretical and methodological progress in the field of text linguistic approaches to media text.

7References

Aarseth, Espen J. (1997), Cybertext: Perspectives on Ergodic Literature, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press.

Aguaded Gómez, José Ignacio (2000), El discurso televisivo: los fundamentos semiológicos de la televisión, <http://cvonline.uaeh.edu.mx/Cursos/Especialidad/TecnologiaEducativaG13/Modulo4/unidad%203s1/lec_3_el_discurso_televisivo.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Almela Pérez, Ramón (1999), Hipertexto. ¿Una clase de texto?, Revista de Investigación Lingüística 2:2, 11–19.

Aumont, Jacques/Marie, Michel (1988), Análisis del film, Barcelona, Paidós.

Bachmann, Iris (2010), “Planeta Brasil”: Language Practices and the construction of space on Brasilia TV abroad, in: Sally Johnson/Tommaso Milan (edd.), Language Ideologies and Media Discourses. Text, Practices, Politics, London/New York, Continuum, 81–100.

Bachmann, Iris (2011a), “A Gente é Latino”. The Making of New Cultural Spaces in Brazilian Diaspora Television, in: Nuria Lorenzo-Dus (ed.), Spanish at Work: Analysing Institutional Discourse across the Spanish-Speaking World, London, Palgrave Macmillan, 50–66.

Bachmann, Iris (2011b), Norm and Variation on Brazilian TV Evening News Programmes: The Case of Third-Person Direct-Object Anaphoric Reference, Bulletin of Hispanic Studies 88:1, 1–22.

Bateman, John (2014), Text and Image. A Critical Introduction to the Visual/Verbal Divide, New York, Routledge.

Bateman, John/Kepser, Matthias/Kuhn, Markus (edd.) (2013), Film, Text, Kultur. Beiträge zur Textualität des Films, Marburg, Schüren.

Bateman, John/Schmidt, Karl-Heinrich (2011), Multimodal Film Analysis. How film means, New York, Routledge.

Beaugrande, Robert Alain de/Dressler, Wolfgang U. (1981), Einführung in die Textlinguistik, Tübingen, Niemeyer.

Blüher, Dominique/Kessler, Frank/Tröhler, Margrit (1999), Film als Text. Theorie und Praxis der “analyse textuelle”, <http://www.montage-av.de/pdf/081_1999/08_1_Blueher_Kessler_Troehler_Film_als_Text.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Bucher, Hans-Jürgen (2010), Multimodalität – eine Universalie des Medienwandels: Problemstellungen und Theorien der Multimodalitätsforschung, in: Hans-Jürgen Bucher (ed.), Neue Medien – neue Formate: Ausdifferenzierung und Konvergenz in der Medienkommunikation, Frankfurt am Main, Campus, 41–79.

Bucher, Hans-Jürgen (2013), Online-Diskurse als multimodale Netzwerk-Kommunikation. Plädoyer für eine Paradigmenerweiterung, in: Claudia Fraas/Stefan Meier/Christian Pentzold (edd.), Online-Diskurse. Theorien und Methoden transmedialer Online-Diskursforschung, Magdeburg, von Halem, 57–101.

Burda, Hubert/Maar, Christa (edd.) (2004), Iconic Turn: Die neue Macht der Bilder, Köln, Du Mont.

Canavilhas, João Messias (2008), Hipertexto e recepção de notícias online, <http://www.bocc.ubi.pt/pag/canavilhas-joao-hipertexto-e-recepcao-noticias-online.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Eckkrammer, Eva Martha (1999), Kontrastive Textologie, Wien, Praesens.

Eckkrammer, Eva Martha/Held, Gudrun (2006), Textsemiotik – Plädoyer für eine erweiterte Konzeption der Textlinguistik zur Erfassung der multimodalen Realität, in: Eva Martha Eckkrammer/Gudrun Held (edd.), Textsemiotik. Studien zu multimodalen Texten, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang, 1–10.

Eder, Hildegund Maria/Eckkrammer, Eva Martha (2000), Cyber-Diskurs zwischen Konvention und Revolution. Eine multilinguale textlinguistische Analyse von Gebrauchstextsorten im realen und virtuellen Raum, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang.

Franco, Mario (2005), Spanische Weblogs, in: Peter Schlobinski/Torsten Siever (edd.), Sprachliche und textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. Ein internationales Projekt, Networx 46, <http://www.mediensprache.net/networx/networx-46.pdf> (07.10.2016), 288–319.

Friess, Regina (2011), Narrative versus spielerische Rezeption? Eine Fallstudie zum interaktiven Film, Wiesbaden, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

García Escrivá, Vicente (2011), Análisis textual de “Apocalypse Now”, Memoria para optar al grado de doctor, <http://eprints.ucm.es/13417/1/T33161.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Genette, Gérard (1987), Seuils, Paris, Seuil.

Gómez Tarín, Francisco Javier (2006), El análisis del texto fílmico, <http://www.bocc.ubi.pt/pag/tarin-francisco-el-analisis-del-texto-filmico.pdf> (07.10.2016).

González Requena, Jesús (1988), El discurso televisivo: espectáculo de la posmodernidad, Madrid, Cátedra.

Gutierrez Gonzalez, Zeli Miranda (2007), Lingüística de corpus na análise do internetês, Dissertação, Pontifícia Universidade Católica de São Paulo, <http://www.leffa.pro.br/tela4/Textos/Textos/Dissertacoes/disserta_201_220/Zeli_Gonzalez.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Henckel von Donnersmarck, Florian (2006), Das Leben der Anderen, Wiedemann&Berg Filmproduktion.

Hickethier, Knut (2010), Einführung in die Medienwissenschaft, Stuttgart/Weimar, Metzler.

Hickethier, Knut (2012), Film- und Fernsehanalyse, Stuttgart/Weimar, Metzler.

Hofmann, Sabine (2011), Sprache im Massenmedium Fernsehen: Sprachliches Design, sprachliche Variation und mediale Räume in Lateinamerika, Tübingen, Narr.

Huber, Oliver (2002), Hypertextlinguistik. TAH: Ein textlinguistisches Analysemodell für Hypertexte. Theoretisch und praktisch exemplifiziert am Problemfeld der typisierten Links von Hypertexten im World Wide Web, Inauguraldissertation, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, <https://edoc.ub.uni-muenchen.de/921/1/Huber_Oliver.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Jakobs, Eva-Maria (2003), Hypertextsorten, Zeitschrift für germanistische Linguistik 31, 232–273.

Jakobs, Eva-Maria/Lehnen, Katrin (2005), Hypertext – Klassifikation und Evaluation, in: Torsten Siever/Peter Schlobinski/Jens Runkehl (edd.), Websprache.net. Sprache und Kommunikation im Internet, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter, 159–184.

Kress, Gunther (2010), Multimodality. A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication, New York, Routledge.

Kress, Gunther/van Leeuwen, Theo (1996), Reading Images. The Grammar of Visual Design. London/New York, Routledge.

Kress, Gunther/van Leeuwen, Theo (2001), Multimodal Discourse. The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication, London, Hodder Education.

Lamarca Lapuente, María Jesús (2013), Hipertexto: El nuevo concepto de documento en la cultura de la imagen, Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, <http://www.hipertexto.info> (07.10.2016).

Magnabosco, Gislaine Gracia (2010), Contribuições da linguística textual para a análise da coerência em hipertextos, Texto livre: Linguagem e technologia 3:1, <http://www.periodicos.letras.ufmg.br/index.php/textolivre/article/view/46/7292> (07.10.2016).

Martins, Simone (2008), A Construção da Identidade das Telenovelas Brasileiras: O Processo de Identificação dos Telespectadores com a Narrativa Ficcional Televisiva, <http://www.ufrgs.br/alcar/encontros-nacionais-1/encontros-nacionais/6o-encontro-2008-1/A%20Construcao%20da%20Identidade%20das%20Telenovelas%20Brasileiras.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Mehler, Alexander, et al. (2008), Sprachliche Netzwerke, in: Christian Stegbauer (ed.), Netzwerkanalyse und Netzwerktheorie. Ein neues Paradigma in den Sozialwissenschaften, Wiesbaden, VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften, 413–427.

Metz, Christian (1971), Langage et cinéma, Paris, Larousse.

Miles, Adrian (1999), Cinematic Paradigms for Hypertext, Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies 13:2, 217–226.

Pang, Alfred (2004), Making history in From Colony to Nation: a multimodal analysis of a museum exhibition in Singapore, in: Kay O’Halloran (ed.), Multimodal Discourse Analysis. System-Functional Perspectives, London, Continuum, 28–54.

Pérez Marco, Sonia (2003), El concepto de hipertexto en el periodismo digital: análisis de la aplicación del hipertexto en la estructuración de las noticias de las ediciones digitales de tres periódicos españoles (<www.elpais.es, www.elmundo.es, www.abc.es), Tesis Doctoral, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, http://biblioteca.ucm.es/tesis/inf/ucm-t26795.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Porto, Mauro (2012), Media Power and Democratization in Brazil. TV Globo and the Dilemmas of Political Accountability, New York/London, Routledge.

Sachs-Hombach, Klaus (ed.) (2005), Bildwissenschaft. Disziplinen, Themen, Methoden, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp.

Sachs-Hombach, Klaus (ed.) (2009), Bildtheorien: Anthropologische und kulturelle Grundlagen des Visualistic Turn, Frankfurt am Main, Suhrkamp.

Sandig, Barbara (1997), Sprech- und Gesprächsstile, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter.

Santanilla Cala, Diana Carolina (2009), Análisis semiótico-visual de películas ganadoras a mejor fotografía en el Festival de San Sebastián. Tesis Doctoral, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Bogotá, <http://javeriana.edu.co/biblos/tesis/comunicacion/tesis174.pdf> (07.10.2016)

Schlobinski, Peter/Siever, Torsten (edd.) (2005), Sprachliche und textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. Ein internationales Projekt, Networx 46, <http://www.mediensprache.net/networx/networx-46.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Schmitz, Ulrich (2011), Sehflächenforschung. Eine Einführung, in: Hajo Diekmannshenke/Michael Klemm/Hartmut Stöckl (edd.), Bildlinguistik. Theorien – Methoden – Fallbeispiele, Berlin, Schmidt, 23–42.

Schrader-Kniffki, Martina (2012), Das französische Internetforum “Français notre belle langue”: Kommunikativer Raum und (meta-)sprachliches Netzwerk zwischen Virtualität und Realität, in: Annette Gerstenberg/Claudia Polzin-Haumann/Dietmar Osthus (edd.), Sprache und Öffentlichkeit in realen und virtuellen Räumen, Bonn, Romanistischer Verlag, 251–271.

Sieberg, Bernd (2005), Sprachliche und textuelle Aspekte in portugiesischen Weblogs, in: Peter Schlobinski/Torsten Siever (edd.), Sprachliche und textuelle Merkmale in Weblogs. Ein internationales Projekt, Networx 46, <http://www.mediensprache.net/networx/networx-46.pdf> (07.10.2016), 198–224.

Spitzmüller, Jürgen/Warnke, Ingo (2011), Diskurslinguistik. Eine Einführung in Theorien und Methoden der transtextuellen Sprachanalyse, Berlin/Boston, de Gruyter.

Stöckl, Hartmut (2004), Die Sprache im Bild – Das Bild der Sprache. Zur Verknüpfung von Sprache und Bild im massenmedialen Text. Konzepte – Theorien – Analysemethoden, Berlin/New York, de Gruyter.

Stöckl, Hartmut (2006), Zeichen, Text und Sinn – Theorie und Praxis der multimodalen Textanalyse, in: Eva Martha Eckkrammer/Gudrun Held (edd.), Textsemiotik. Studien zu multimodalen Texten, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang, 11–36.

Stöckl, Hartmut (2012), Medienlinguistik. Zu Status und Methodik eines (noch) emergenten Forschungsfeldes, in: Christian Grösslinger/Gudrun Held/Hartmut Stöckl (edd.), Pressetextsorten jenseits der “News”: Medienlinguistische Perspektiven auf journalistische Kreativität, Frankfurt am Main et al., Lang, 13–34.

Sutter, Tilmann/Mehler, Alexander (edd.) (2010), Medienwandel als Wandel von Interaktionsformen, Wiesbaden, VS-Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Vater, Heinz (2005), Einführung in die Textlinguistik, München, Fink.

Vergara Heidke, Adrián (2010), El discurso alarmista en la televisión en Costa Rica: El discurso sobre la criminalidad en los textos informativos, Dissertation, Universität Bremen, <http://elib.suub.uni-bremen.de/edocs/00101998-1.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Vieira Barbosa, Maria Lourdilene/Barbosa de Sousa, Emanoel (2013), A relação entre portais de notícias e hipertextualidade, <http://evidosol.textolivre.org/papers/2013/upload/23.pdf> (07.10.2016).

Wildfeuer, Janina (2013a), Der Film als Text? Ein Definitionsversuch aus linguistischer Sicht, in: John Bateman/Matthis Kepser/Markus Kuhn (edd.), Film, Text, Kultur. Beiträge zur Textualität des Films, Marburg, Schüren, 32–57.

Wildfeuer, Janina (2013b), Der neue interaktive Film. Zu hybriden Filmformen im Internet und der Adaption eines Genrebegriffs, Rabbit Eye – Zeitschrift für Filmforschung 5, 56–70.

Wildfeuer, Janina (2014), Film Discourse Interpretation. Towards a New Paradigm for Multimodal Film Analysis, New York, Routledge.

Wildfeuer, Janina/Bateman, John A. (edd.) (2017), Film Text Analysis: New Perspectives on the Analysis of Filmic Meaning, London/New York, Routledge.

Ziegler, Arne (2002), E-Mail – Textsorte oder Kommunikationsform? Eine textlinguistische Annäherung, in: Arne Ziegler/Christa Dürscheid (edd.), Kommunikationsform E-Mail, Tübingen, Stauffenburg, 9–32.